Mapping Glacial Lakes in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Data

2.3. Glacial Lake Mapping

2.3.1. Data Preparation

2.3.2. Glacial Lake Delineation

- Supraglacial lakes (SGLs) form in topographical depressions on the surface of glaciers;

- Moraine-dammed lakes (MDLs) form behind terminal or lateral moraines;

- Glacial erosion lakes (GELs) form in topographical depressions in the bedrock.

2.3.3. Accuracy Assessment

2.3.4. Glacial Lake Size Distribution

3. Results

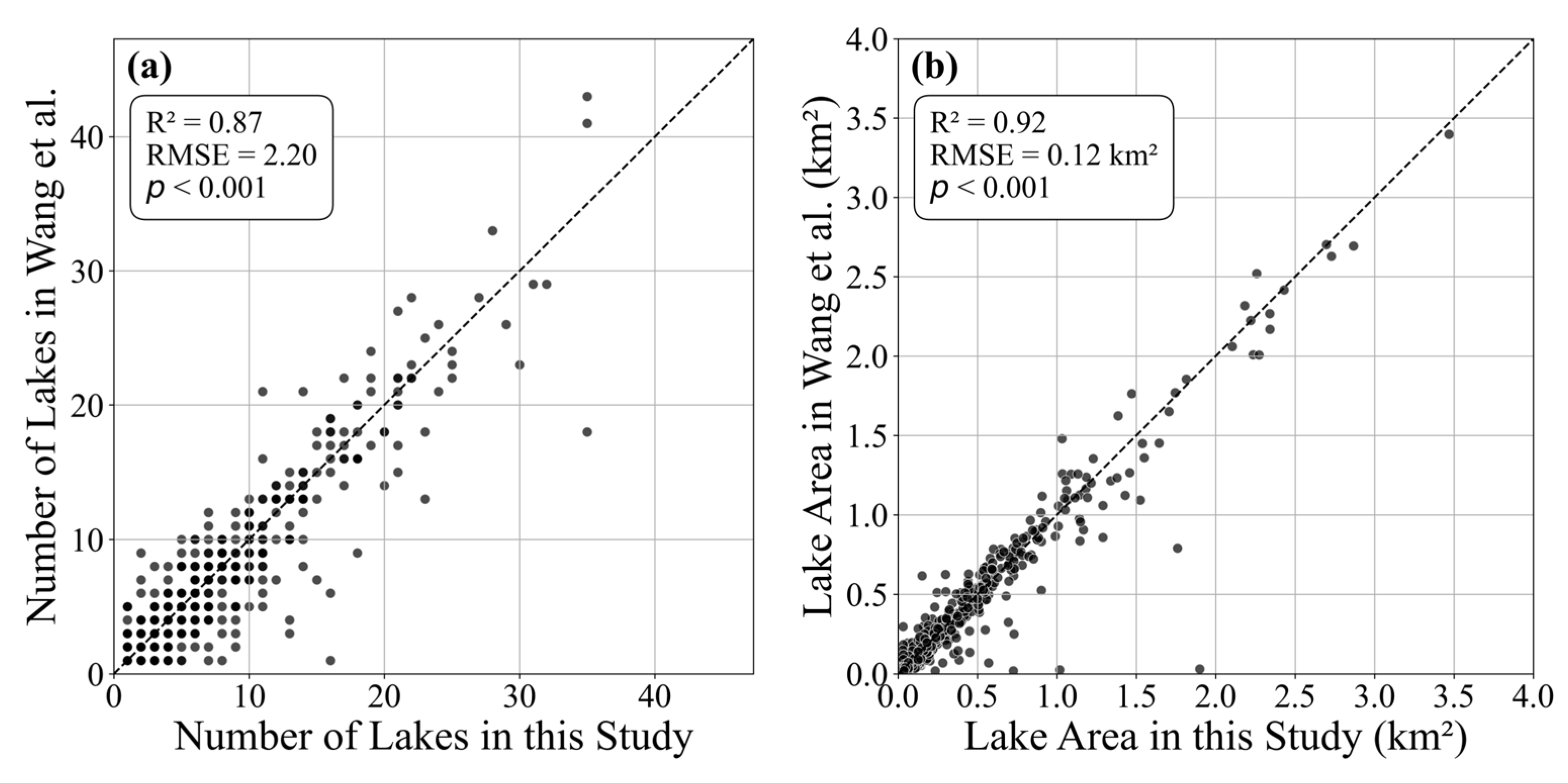

3.1. SAR-Based Lake Mapping and Accuracy Assessment

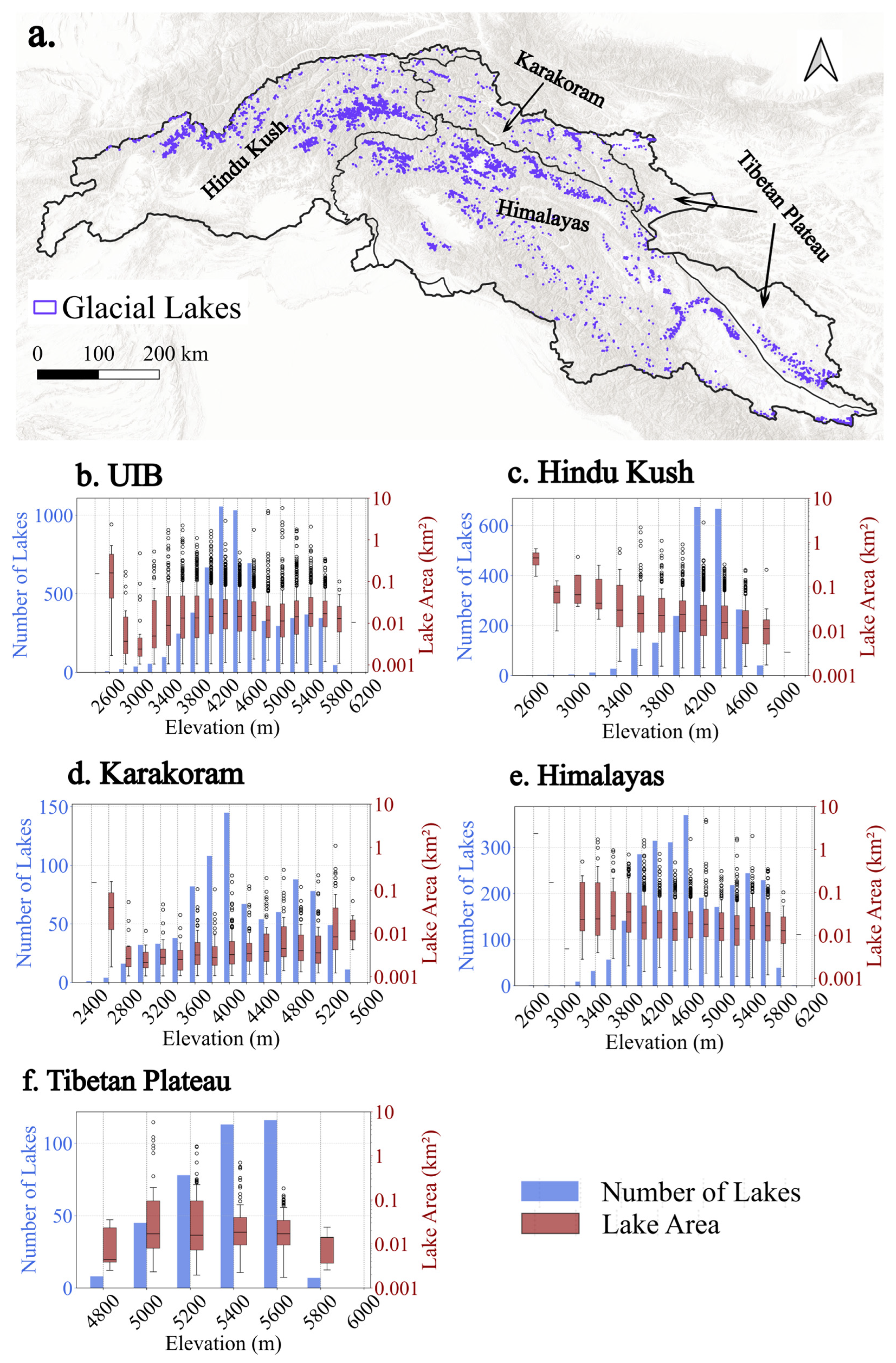

3.2. Glacial Lake Area and Elevation Distribution

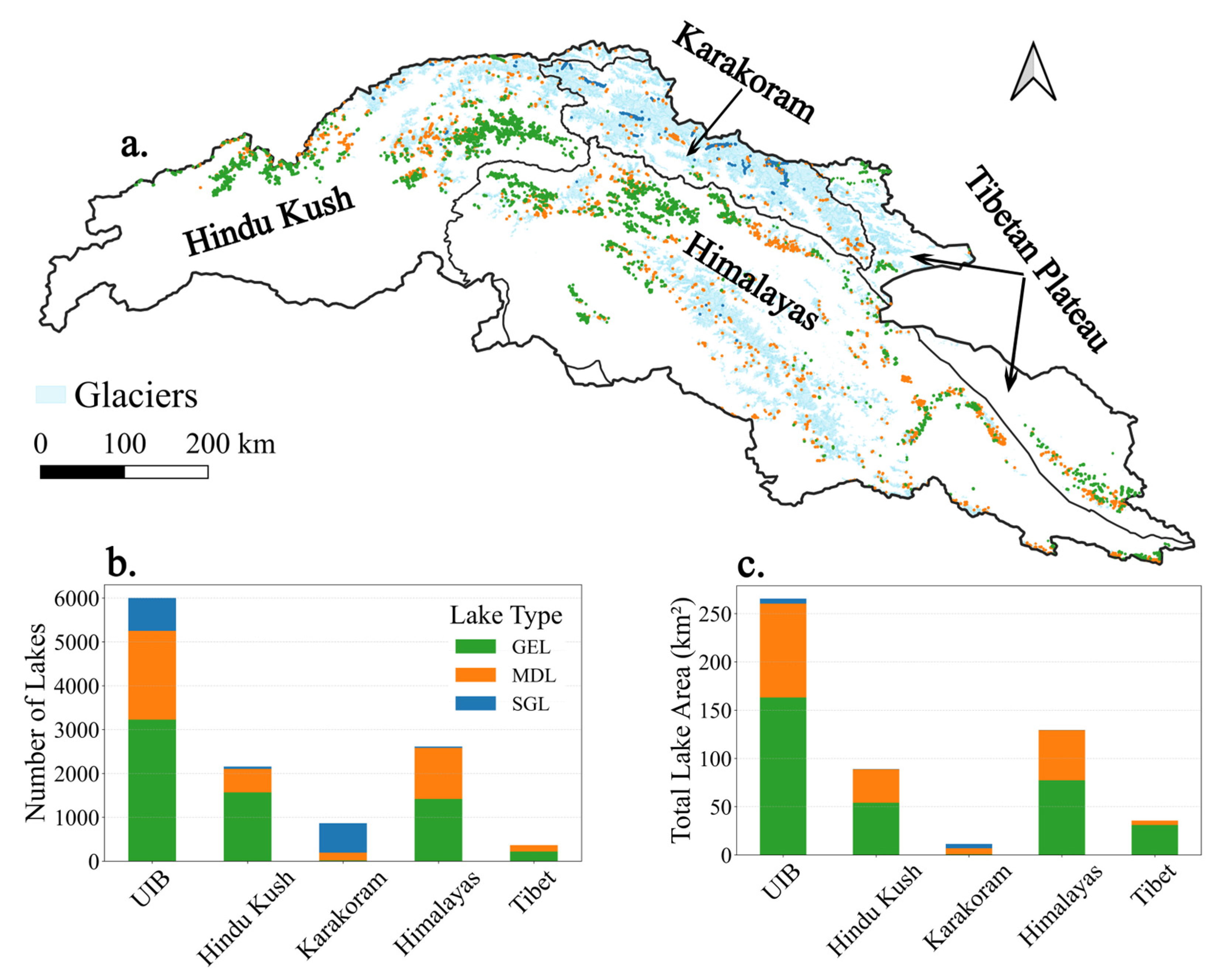

3.3. Glacial Lake Type Distribution

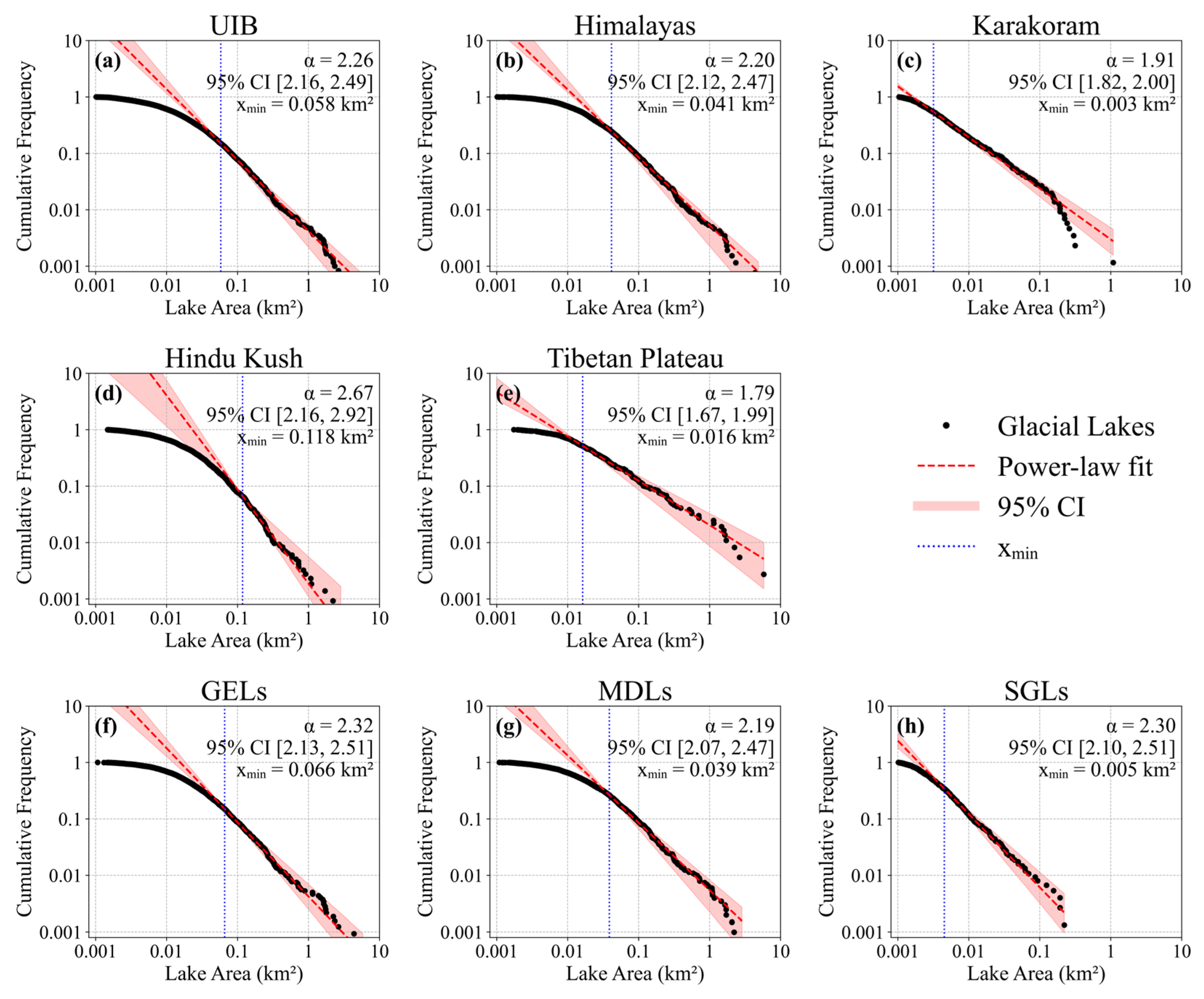

3.4. Power Law Distribution of Glacial Lake Area

4. Discussion

4.1. SAR-Based Glacial Lake Inventory and Comparison with Other Datasets

4.2. Spatial Characteristics of Glacial Lake Distribution

4.3. Power-Law Distribution of Glacial Lake Area

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α | Power-law Exponent |

| CCDF | Complementary Cumulative Distribution Function |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GEL | Glacial Erosion Lake |

| GLOF | Glacial Lake Outburst Flood |

| GRD | Ground Range Detected |

| HMA | High Mountain Asia |

| IW | Interferometric Wide Swath |

| KS | Kolmogorov–Smirnov Statistic |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percent Error |

| MDL | Moraine-dammed Lake |

| NDSI | Normalized Difference Snow Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| RGI | Randolph Glacier Inventory |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| S1 | Sentinel-1 |

| S2 | Sentinel-2 |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SGL | Supraglacial Lake |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| UIB | Upper Indus Basin |

| VV | Vertical transmit—Vertical receive Polarization |

| xmin | Minimum Area Threshold (Power-law distribution) |

References

- Roe, G.H.; Baker, M.B.; Herla, F. Centennial Glacier Retreat as Categorical Evidence of Regional Climate Change. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F.; et al. Accelerated Global Glacier Mass Loss in the Early Twenty-First Century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GlaMBIE Team; Zemp, M.; Jakob, L.; Dussaillant, I.; Nussbaumer, S.U.; Gourmelen, N.; Dubber, S.; Geruo, A.; Abdullahi, S.; Andreassen, L.M.; et al. Community Estimate of Global Glacier Mass Changes from 2000 to 2023. Nature 2025, 639, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.; Glasser, N.F.; Reynolds, J.M.; Harrison, S.; Anacona, P.I.; Schaefer, M.; Shannon, S. Glacial Lakes of the Central and Patagonian Andes. Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 162, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugar, D.H.; Burr, A.; Haritashya, U.K.; Kargel, J.S.; Watson, C.S.; Kennedy, M.C.; Bevington, A.R.; Betts, R.A.; Harrison, S.; Strattman, K. Rapid Worldwide Growth of Glacial Lakes since 1990. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, Z. Glacial Lake Inventory of High-Mountain Asia in 1990 and 2018 Derived from Landsat Images. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2169–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Fan, C.; Ma, J.; Zhan, P.; Deng, X. A Spatially Constrained Remote Sensing-Based Inventory of Glacial Lakes Worldwide. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Kargel, J.S.; Huggel, C.; Reynolds, J.; Shugar, D.H.; Betts, R.A.; Emmer, A.; Glasser, N.; Haritashya, U.K.; Klimeš, J.; et al. Climate Change and the Global Pattern of Moraine-Dammed Glacial Lake Outburst Floods. Cryosphere 2018, 12, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, A.; Harrison, S.; Mergili, M.; Allen, S.; Frey, H.; Huggel, C. 70 Years of Lake Evolution and Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in the Cordillera Blanca (Peru) and Implications for the Future. Geomorphology 2020, 365, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, P.; Messerli, A.; Mätzler, E.; Santoro, M.; Wiesmann, A.; Caduff, R.; Langley, K.; Bojesen, M.H.; Paul, F.; Kääb, A.; et al. Greenland-Wide Inventory of Ice Marginal Lakes Using a Multi-Method Approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Song, C.; Wang, Y. Spatially and Temporally Resolved Monitoring of Glacial Lake Changes in Alps During the Recent Two Decades. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 723386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölg, N.; Huggel, C.; Herold, T.; Storck, F.; Allen, S.; Haeberli, W.; Schaub, Y.; Odermatt, D. Inventory and Evolution of Glacial Lakes since the Little Ice Age: Lessons from the Case of Switzerland. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2021, 46, 2551–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Maheshwari, R.; Sweta; Guru, N.; Rao, B.S.; Raju, P.V.; Rao, V.V. Updated Glacial Lake Inventory of Indus River Basin Based on High-Resolution Indian Remote Sensing Satellite Data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, B.; McGrath, D.; Armstrong, W.; McCoy, S.W. Dam Type and Lake Location Characterize Ice-Marginal Lake Area Change in Alaska and NW Canada between 1984 and 2019. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Yang, W. An Inventory of Glacial Lakes in the Third Pole Region and Their Changes in Response to Global Warming. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 131, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Tian, B. An Automated Method for Glacial Lake Mapping in High Mountain Asia Using Landsat 8 Imagery. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, N. Recent Changes of Glacial Lakes in the High Mountain Asia and Its Potential Controlling Factors Analysis. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, M.; Guo, H.; Allen, S.; Kargel, J.S.; Haritashya, U.K.; Watson, C.S. Annual 30 m Dataset for Glacial Lakes in High Mountain Asia from 2008 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 741–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, G.; Zhang, R.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Monitoring Dynamic Evolution of the Glacial Lakes by Using Time Series of Sentinel-1A SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, T.; Wiesmann, A.; Kääb, A.; Joshi, S.; Mool, P. Glacial Lake Mapping with Very High Resolution Satellite SAR Data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2487–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Tian, B.; Liang, D.; Yang, A. High-Frequency Glacial Lake Mapping Using Time Series of Sentinel-1A/1B SAR Imagery: An Assessment for the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirscherl, M.; Dietz, A.J.; Kneisel, C.; Kuenzer, C. A Novel Method for Automated Supraglacial Lake Mapping in Antarctica Using Sentinel-1 SAR Imagery and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendleder, A.; Schmitt, A.; Erbertseder, T.; D’Angelo, P.; Mayer, C.; Braun, M.H. Seasonal Evolution of Supraglacial Lakes on Baltoro Glacier From 2016 to 2020. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 725394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, L. Investigating the Seasonal Dynamics of Surface Water over the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Using Sentinel-1 Imagery and a Novel Gated Multiscale ConvNet. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 1372–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, K.E.; Willis, I.C.; Benedek, C.L.; Williamson, A.G.; Tedesco, M. Toward Monitoring Surface and Subsurface Lakes on the Greenland Ice Sheet Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Landsat-8 OLI Imagery. Front. Earth Sci. 2017, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, S.; Bolch, T. Mapping of Glacial Lakes Using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data and a Random Forest Classifier: Strengths and Challenges. Sci. Remote Sens. 2020, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, G.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Cai, J.; Xiang, W. A Deep Learning Method for Mapping Glacial Lakes from the Combined Use of Synthetic-Aperture Radar and Optical Satellite Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, A.; Yao, T. Rapid Expansion of Glacial Lakes Caused by Climate and Glacier Retreat in the Central Himalayas: Rapid Expansion of Glacial Lakes in the Central Himalayas. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.S.; King, O.; Miles, E.S.; Quincey, D.J. Optimising NDWI Supraglacial Pond Classification on Himalayan Debris-Covered Glaciers. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racoviteanu, A.; Williams, M.; Barry, R. Optical Remote Sensing of Glacier Characteristics: A Review with Focus on the Himalaya. Sensors 2008, 8, 3355–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawak, S.D.; Bidawe, T.G.; Luis, A.J. A Review on Applications of Imaging Synthetic Aperture Radar with a Special Focus on Cryospheric Studies. Adv. Remote Sens. 2015, 04, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.F.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Kraaijenbrink, P.D.; Shrestha, A.B.; Bierkens, M.F. Climate Change Impacts on the Upper Indus Hydrology: Sources, Shifts and Extremes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, S.R.; Shrestha, B. The Status of Glaciers in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan Region; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RGI Consortium. Randolph Glacier Inventory—A Dataset of Global Glacier Outlines, Version 6; National Snow and Ice Data Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, A.; Rupper, S.; Keeler, D.; Johnson, E.; Forster, R. Indus River Basin Glacier Melt at the Subbasin Scale. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 767411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.F.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Shrestha, A.B.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Consistent Increase in High Asia’s Runoff Due to Increasing Glacier Melt and Precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.F.; Kargel, J.S.; Shea, J.M.; Nepal, S.; Haritashya, U.K.; Srivastava, S.; Maussion, F.; Qazi, N.; Chevallier, P.; Dimri, A.P.; et al. Glaciohydrology of the Himalaya-Karakoram. Science 2021, 373, eabf3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, A.; Ahmad, B.; Alam, U.; Appadurai, A.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Biemans, H.; Bolch, T.; Chaulagain, N.P.; Dhaubanjar, S.; Dimri, A.P.; et al. Knowledge Priorities on Climate Change and Water in the Upper Indus Basin: A Horizon Scanning Exercise to Identify the Top 100 Research Questions in Social and Natural Sciences. Earths Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, W.W.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Asia’s Water Balance. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.; Forster, R.R.; Rupper, S.B.; Deeb, E.J.; Marshall, H.P.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Burgess, E. Mapping Snowmelt Progression in the Upper Indus Basin With Synthetic Aperture Radar. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 7, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.; Hashmi, M.Z.U.R.; Ahmed, S.I.; Anees, M. Assessing Climate Sensitivity of the Upper Indus Basin Using Fully Distributed, Physically-Based Hydrologic Modeling and Multi-Model Climate Ensemble Approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.; Othman, A.A.; Merkel, B.; Hasan, S.E. Change Detection of Glaciers and Snow Cover and Temperature Using Remote Sensing and GIS: A Case Study of the Upper Indus Basin, Pakistan. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2020, 18, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, C.P. Glaciochemical Investigations as a Tool for Determining the Spatial and Seasonal Variation of Snow Accumulation in the Central Karakoram, Northern Pakistan. Ann. Glaciol. 1989, 13, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maussion, F.; Scherer, D.; Mölg, T.; Collier, E.; Curio, J.; Finkelnburg, R. Precipitation Seasonality and Variability over the Tibetan Plateau as Resolved by the High Asia Reanalysis. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 1910–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookhagen, B.; Burbank, D.W. Toward a Complete Himalayan Hydrological Budget: Spatiotemporal Distribution of Snowmelt and Rainfall and Their Impact on River Discharge. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, F03019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Pritchard, H.D.; Liu, Q.; Hennig, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Nepal, S.; Samyn, D.; Hewitt, K.; et al. Glacial Change and Hydrological Implications in the Himalaya and Karakoram. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Cao, J.; Hussain, I.; Begum, S.; Akhtar, M.; Wu, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhou, J. Observed Trends and Variability of Temperature and Precipitation and Their Global Teleconnections in the Upper Indus Basin, Hindukush-Karakoram-Himalaya. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Koch, M. Correction and Informed Regionalization of Precipitation Data in a High Mountainous Region (Upper Indus Basin) and Its Effect on SWAT-Modelled Discharge. Water 2018, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, B.; Vanhuysse, S.; Grippa, T.; Flasse, C.; Wolff, E. Using Sentinel-1 and Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing for Detecting Historical Flood Hazards in Tropical Urban Regions: A Case of Dar Es Salaam. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2202296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsaie, R.; Ghaderi, D. Comparison of Efficiency of Spectral (NDWI) and SAR (GRD) Method in Shoreline Detection: A Novel Method of Integrating GRD and SLC Products of Sentinel-1 Satellite. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 84, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Li, S.; Hajnsek, I.; Siddique, M.A.; Hong, W.; Wu, Y. Glacial Lake Mapping Using Remote Sensing Geo-Foundation Model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 136, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, 2005RG000183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, A.; Mullissa, A.; Reiche, J. Angular-Based Radiometric Slope Correction for Sentinel-1 on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullissa, A.; Vollrath, A.; Odongo-Braun, C.; Slagter, B.; Balling, J.; Gou, Y.; Gorelick, N.; Reiche, J. Sentinel-1 SAR Backscatter Analysis Ready Data Preparation in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D. Flattening Gamma: Radiometric Terrain Correction for SAR Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 3081–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yao, X.; Duan, H.; Yang, J.; Pang, W. Inventory of Glacial Lake in the Southeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Derived from Sentinel-1 SAR Image and Sentinel-2 MSI Image. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstott, J.; Bullmore, E.; Plenz, D. Powerlaw: A Python Package for Analysis of Heavy-Tailed Distributions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Shalizi, C.R.; Newman, M.E.J. Power-Law Distributions in Empirical Data. SIAM Rev. 2009, 51, 661–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, S.; Bolch, T.; Robson, B.A. Monitoring Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Susceptibility Using Sentinel-1 SAR Data, Google Earth Engine, and Persistent Scatterer Interferometry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jia, L.; Ma, X.; Lei, Z. Development Genetic and Stability Classification of Seasonal Glacial Lakes in a Tectonically Active Area—A Case Study in Niangmuco, East Margin of the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1361889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, K. Glacier Change, Concentration, and Elevation Effects in the Karakoram Himalaya, Upper Indus Basin. Mt. Res. Dev. 2011, 31, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romshoo, S.A.; Abdullah, T.; Ameen, U.; Bhat, M.H. Glacier Thickness and Volume Estimation in the Upper Indus Basin Using Modeling and Ground Penetrating Radar Measurements. Ann. Glaciol. 2023, 64, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Sheng, Y. Contrasting Evolution Patterns between Glacier-Fed and Non-Glacier-Fed Lakes in the Tanggula Mountains and Climate Cause Analysis. Clim. Change 2016, 135, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Duan, S.-B.; Dai, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, M. Mapping of Lakes in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 2016 to 2021: Trend and Potential Regularity. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 1692–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Shen, G. Patterns and Potential Drivers of Dramatic Changes in Tibetan Lakes, 1972–2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Piao, S.; Bolch, T.; Xie, H.; Chen, D.; Gao, Y.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Shum, C.K.; Yang, K.; et al. Extensive and Drastically Different Alpine Lake Changes on Asia’s High Plateaus during the Past Four Decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Nagarajan, R. Glacial Lake Inventory and Evolution in Northwestern Indian Himalaya. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 5284–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Bhuiyan, C. Glacial Lakes of Sikkim Himalaya: Their Dynamics, Trends, and Likely Fate—A Timeseries Analysis through Cloud-Based Geocomputing, and Machine Learning. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2286903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, L.; Maiti, S.; Dixit, A. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Regional Scale Evolution and Distribution of Glacial Lakes in Himalaya. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1038777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Das, S.; Mandal, S.T.; Sharma, M.C.; Ramsankaran, R. Inventory and GLOF Susceptibility of Glacial Lakes in Chenab Basin, Western Himalaya. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2356216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Yunus, A.P.; Xiong, J.; Tang, R.; Lovati, M.; van Westen, C.; Xu, Q. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Glacial Lakes in the Tibetan Plateau over the Past 30 Years. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckel, J.; Otto, J.C.; Prasicek, G.; Keuschnig, M. Glacial Lakes in Austria—Distribution and Formation since the Little Ice Age. Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 164, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.L.; Harrison, S.; Wilson, R.; Emmer, A.; Yarleque, C.; Glasser, N.F.; Torres, J.C.; Caballero, A.; Araujo, J.; Bennett, G.L.; et al. Contemporary Glacial Lakes in the Peruvian Andes. Glob. Planet. Change 2021, 204, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroczek, T.; Vilímek, V. Glacial Lakes Inventory and Susceptibility Assessment in the Alsek River Basin, Yukon, Canada. Geoenviron. Disasters 2024, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonia, D.; Torres, J.; Haeberli, W.; Schauwecker, S.; Braendle, E.; Giraldez, C.; Cochachin, A. Compiling an Inventory of Glacier-Bed Overdeepenings and Potential New Lakes in De-Glaciating Areas of the Peruvian Andes: Approach, First Results, and Perspectives for Adaptation to Climate Change. Water 2017, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, O.; Dehecq, A.; Quincey, D.; Carrivick, J. Contrasting Geometric and Dynamic Evolution of Lake and Land-Terminating Glaciers in the Central Himalaya. Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 167, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.B.G.; Kumar, K.V. Inventory of Glacial Lakes and Its Evolution in Uttarakhand Himalaya Using Time Series Satellite Data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2016, 44, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Carrivick, J.L.; Quincey, D.J.; Cook, S.J.; James, W.H.M.; Brown, L.E. Accelerated Mass Loss of Himalayan Glaciers since the Little Ice Age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinotti, D.; Immerzeel, W.W.; De Kok, R.J.; Quincey, D.J.; Dehecq, A. Manifestations and Mechanisms of the Karakoram Glacier Anomaly. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Li, Y.; Yi, C.; Xu, X. Glacial Changes in the Hunza Basin, Western Karakoram, since the Little Ice Age. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 562, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Song, C. A Regional-Scale Assessment of Himalayan Glacial Lake Changes Using Satellite Observations from 1990 to 2015. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 189, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendleder, A.; Friedl, P.; Mayer, C. Impacts of Climate and Supraglacial Lakes on the Surface Velocity of Baltoro Glacier from 1992 to 2017. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Han, L.; Sun, M.; Zhao, L. Definition and Classification System of Glacial Lake for Inventory and Hazards Study. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.D.; Reynolds, J.M. An Overview of Glacial Hazards in the Himalayas. Quat. Int. 2000, 65–66, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuri, S.; Salerno, F.; Bolch, T.; Guyennon, N.; Tartari, G. Factors Controlling the Accelerated Expansion of Imja Lake, Mount Everest Region, Nepal. Ann. Glaciol. 2016, 57, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritashya, U.K.; Kargel, J.S.; Shugar, D.H.; Leonard, G.J.; Strattman, K.; Watson, C.S.; Shean, D.; Harrison, S.; Mandli, K.T.; Regmi, D. Evolution and Controls of Large Glacial Lakes in the Nepal Himalaya. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, O.; Bhattacharya, A.; Bhambri, R.; Bolch, T. Glacial Lakes Exacerbate Himalayan Glacier Mass Loss. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.M.; Schaefer, J.M.; Rupper, S.; Corley, A. Acceleration of Ice Loss across the Himalayas over the Past 40 Years. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronk, J.B.; Bolch, T.; King, O.; Wouters, B.; Benn, D.I. Contrasting Surface Velocities between Lake- and Land-Terminating Glaciers in the Himalayan Region. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 5577–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, D.; Evans, D.J.A. Glaciers and Glaciation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Nagarajan, R. Glacial Lake Changes and Outburst Flood Hazard in Chandra Basin, North-Western Indian Himalaya. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2018, 9, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, A.; Wood, J.L.; Cook, S.J.; Harrison, S.; Wilson, R.; Diaz-Moreno, A.; Reynolds, J.M.; Torres, J.C.; Yarleque, C.; Mergili, M.; et al. 160 Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) across the Tropical Andes since the Little Ice Age. Glob. Planet. Change 2022, 208, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturrizaga, L. Glacial and Glacially Conditioned Lake Types in the Cordillera Blanca, Peru: A Spatiotemporal Conceptual Approach. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2014, 38, 602–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, M.J.; Glasser, N.F.; Brasington, J.; Hambrey, M.J.; Quincey, D.J.; Reynolds, J.M. Modelling Outburst Floods from Moraine-Dammed Glacial Lakes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 134, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Water Flow in Glaciers: Jökulhlaups, Tunnels and Veins. J. Glaciol. 1976, 17, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cael, B.B.; Seekell, D.A. The Size-Distribution of Earth’s Lakes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, E.S.; Cooley, S.; Mullen, A.; Webb, E.E.; Watts, J. Glacial History Modifies Permafrost Controls on the Distribution of Lakes and Ponds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL112771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; An, B. A Conceptual Model for Glacial Lake Bathymetric Distribution. Cryosphere 2023, 17, 5137–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; An, B. Heterogeneous Changes in Global Glacial Lakes under Coupled Climate Warming and Glacier Thinning. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Coco, G.; Zhou, Z.; Townend, I.; Guo, L.; He, Q. A Universal Form of Power Law Relationships for River and Stream Channels. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL090493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Howarth, J.D.; Massey, C.I.; Luković, B.; Sirguey, P.; Singeisen, C.; Gasston, C.; Morgenstern, R.; Ries, W. An Alternative to Landslide Volume-Area Scaling Relationships: An Ensemble Approach Adopting a Difference Model to Estimate the Total Volume of Landsliding Triggered by the 2016 Kaikōura Earthquake, New Zealand. Landslides 2025, 22, 2219–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Basin Area (km2) | Lake Count | Total Lake Area (km2) | % of Basin Area | Mean Area (km2) | Mean Lake Elevation (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UIB | 425,000 | 6019 | 266.0 | 0.06 | 0.044 | 4566 |

| Hindu Kush | 134,000 | 2171 | 89.4 | 0.06 | 0.041 | 4323 |

| Karakoram | 40,000 | 866 | 11.4 | 0.03 | 0.013 | 4249 |

| Himalayas | 201,000 | 2615 | 129.6 | 0.06 | 0.050 | 4747 |

| Tibetan Plateau | 50,000 | 367 | 35.6 | 0.07 | 0.100 | 5469 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, I.; Jacobs, J.M.; Johnston, J.M.; Vardaman, M. Mapping Glacial Lakes in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data. Glacies 2025, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/glacies2040013

Khan I, Jacobs JM, Johnston JM, Vardaman M. Mapping Glacial Lakes in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data. Glacies. 2025; 2(4):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/glacies2040013

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Imran, Jennifer M. Jacobs, Jeremy M. Johnston, and Megan Vardaman. 2025. "Mapping Glacial Lakes in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data" Glacies 2, no. 4: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/glacies2040013

APA StyleKhan, I., Jacobs, J. M., Johnston, J. M., & Vardaman, M. (2025). Mapping Glacial Lakes in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) Using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data. Glacies, 2(4), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/glacies2040013