Abstract

This study examines the political and elite motives behind Colombo’s ‘world-class city’ initiative and its impact on public housing in underserved communities. Informed by interviews with high-ranking government officials, including urban planning experts and military officers, this study examines how President Rajapaksa’s elite-driven postwar Sri Lankan government leveraged military capacities within the neoliberal developmental framework to transform Colombo’s urban space for political and economic goals, often at the expense of marginalized communities. Applying a contextual discourse analysis model, which views discourse as a constellation of arguments within a specific context, we critically analyzed interview discussions to clarify the rationale behind the militarized approach to public housing while highlighting its contradictions, including the displacement of underserved communities and the ethical concerns associated with compulsory relocation. The findings suggest that Colombo’s postwar public housing program was utilized to consolidate authoritarian control and promote speculative urban transformation, treating public housing as a secondary aspect of broader political and economic agendas. Anchored in militarized urban governance, these elite-driven strategies failed to achieve their anticipated economic objectives and deepened socio-spatial inequalities, raising serious concerns about exclusionary and undemocratic planning practices. The paper recommends that future urban planning strike a balance between economic objectives and principles of spatial justice, inclusion, and participatory governance, promoting democratic and socially equitable urban development.

1. Introduction

After a 30-year civil war that ended in 2009, President Rajapaksa and the Sri Lankan government, supported by political and elite actors, launched a massive urban regeneration initiative to transform Colombo, the de facto capital of the country, into a world-class city. The aim was to position Colombo as a speculative epicenter capable of attracting foreign investment in urban real estate, in line with the ideal of the East Asian model of ‘neoliberal developmentalism.’ [1]. After the Asian financial crisis in 1997, East Asian developmental states, including Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore, adopted neoliberal political logic alongside their strong government-led development mechanisms, integrating city beautification and aesthetics into their spatial and economic strategies. Postwar Colombo’s aspiration to become a ‘world-class city’ embraced this East Asian idealism, focusing on enhancing the city’s beauty and aesthetics through strong government leadership that intentionally incorporated the military to assist in the urban transformation process.

A notable trend in Sri Lanka’s governmentality was the belief that the responsibility for the country’s development and the welfare of its citizens was an obligation of political society, alongside their supporters in the elite society, including certain government officials, professionals, and senior military personnel [2]. In the postwar effort to transform Colombo into a ‘world-class city’, they believed that the lands occupied by underserved communities (shanties, slums, or dilapidated housing schemes) were underutilized and unattractive, hindering the achievement of ‘world-class’ standards, thus necessitating immediate relocation [3,4]. The initiative to relocate these communities, nearly half of the city’s population, 68,812 families in 1499 underserved settlements—popularly known as the ‘slum-free’ mission—had dual purposes. Firstly, it was presented as part of a city beautification and investment project aimed at freeing 900 acres of land. Secondly, it was emphasized as a significant welfare initiative by the post-war government, aiming to provide housing for low-income communities.

The political authority engaged the military to assist in achieving these dual intentions by placing the Urban Development Authority (UDA), the country’s apex body for urban development, under the purview of the Ministry of Defense (MoD). Concurrently, a new Ministry, the Ministry of Defense and Urban Development (MoD&UD), was established. This new ministry became one of the most influential in the country, overseen by the president, with his brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa—a former military officer and celebrated war hero—serving as the Secretary and controlling its operations. Amarasuriya and Spencer [5], referencing Ssorin-Chaikov’s analysis of late Stalinism, noted Gotabaya as a ‘man in a hurry’ in completing tasks and expediting political and bureaucratic delays, as demonstrated by ending a thirty-year war in just three years, highlighting his reputation for ‘urgency’ [6,7] and efficient task completion along with his authority in advancing Colombo to a ‘world-class city.’ Under his leadership, UDA was empowered, placing top-ranked military officers, including brigadiers, at the center of decision-making, creating a new military unit, and handing over the responsibilities for implementing the ‘world-class city’ initiative. This established the Urban Regeneration Project (URP) to carry out the ‘slum-free’ mission, positioning it as Colombo’s public housing program.

Military-assisted urban development and public housing in postwar Sri Lanka is a unique development mechanism that no other democratic country has practiced, providing a rare empirical case of urban transformation. Moreover, it is not sufficiently explored in contemporary urban studies, especially within planning, spatial justice, and urban governance scholarship, and constitutes the central analytical contribution of this study. Additionally, we observed that the existing scholarly discourse on Sri Lanka’s postwar ‘world-class city’ development and housing predominantly focused on exploring its causes and effects from the perspectives of the communities in underserved settlements while neglecting the perspectives of political and elite groups’ necessity, reasons, and justifications in implementing the program [3,5,8]. This one-sided narrative limits a comprehensive understanding of postwar public housing under the ‘world-class city’ initiative in Sri Lanka. Our interest in undertaking this research is to address this gap and reveal “What are the political and elite motives behind world-class city development, and how have these motives and associated development strategies influenced public housing and socio-spatial justice of the underserved communities in postwar Colombo?” Recognizing the significant role of the government in shaping urban development policies through political and elite decision-making, we aim to investigate Colombo’s ‘slum-free’ mission from political, governmental, and institutional viewpoints. By doing so, we seek to clarify the rationale behind key decisions and their implications for the socio-spatial justice of public housing development within the ‘world-class city’ initiative. To address these questions, we employ a multifaceted theoretical framework that combines military urbanism, elite governance, and spatial justice to assess how rights, equity, and inclusion are negotiated or denied within militarized urban development. We believe that by examining the perspectives of military and government officers involved in Colombo’s ‘world-class city’ development and public housing, we can contribute to a more refined understanding of its impact on the resettlement housing of underserved communities.

This paper is based on interviews with high-ranked government officials, including urban planners and military officers, involved in Colombo’s postwar ‘world-class city’ development and public housing programs. While the postwar period covers the Rajapaksa (2009–2014) and Sirisena (2015–2019) regimes, we concentrate on Rajapaksa, during which the civil-military model was established and evolved. In contrast, we paid less attention to the Sirisena regime, which succeeded Rajapaksa and was characterized by a notable reduction in active military involvement in urban development activities. We used Kumar and Pallathucheril’s [9] contextual discourse analysis model—discourse as a constellation of arguments within a context—to systematically analyze the claims and supporting statements in all interviews. This analysis produced two central themes: Theme 1, Civil-Military Governance and Political Control in Colombo’s Urban Transformation, and Theme 2, Elite Rationalities, Housing Strategies, and Socio-Spatial Consequences in the ‘Slum-Free’ Mission. This paper concludes that Colombo’s postwar public housing project, framed within the ‘world-class city’ initiative, was driven by political, elite, and military motives that prioritized urban aesthetics and speculative real estate over socio-spatial justice, ultimately intensifying inequalities for underserved communities.

The paper is structured into six sections. This introduction guides the paper, providing an overview of critical factors in postwar Colombo’s ‘world-class city’ initiative and its ‘slum-free mission.’ Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework underpinning our study, while Section 3 will explain the methods and materials used. In Section 4, we will elaborate on the primary findings and essential narratives that emerged from our inquiry, and in Section 5, we will discuss them through various theoretical lenses. Finally, Section 6 will offer a conclusion, presenting the key takeaways, implications, and suggestions for future studies derived from this study. Through this analysis, we aim to deepen our understanding of militarized governance and the planning consequences of Colombo’s postwar housing model.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

We attempted to understand postwar Colombo’s world-class urban development and public housing through multiple lenses of ‘neoliberal developmentalism’ [1] (p. 354) and ‘neopatrimonialism’ [10], incorporating elements of ‘spatial justice’ [11]. Our use of these multiple lenses is deliberate, as the postwar regeneration of Colombo—characterized by authoritarian politics, elite dominance, military integration, and exclusionary urban policies that supersede traditional welfare principles—requires a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach, as fragmented theoretical frameworks are inadequate for critically understanding its layered institutional and spatial dynamics.

Heo [1] defines ‘neoliberal developmentalism’ as a blend of neoliberal political rationality and the developmental state’s governmentality, which emerged as the ideal after 1997 in response to the Asian financial crisis, recognizing neoliberalism as the dominant ideology over developmentalism among the nations of tiger economies (Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore). After decolonization, East Asian nations, such as Japan and these tiger economies, formulated their developmental frameworks based on developmentalism, which advocated for decisive political intervention in state functions and market management to promote national interests [12,13,14,15]. According to Greener and Yeo [16], developmentalism involves competent bureaucratic coordination between the state and the market, emphasizing robust bureaucratic organizing, centralized technocratic planning, state control of all aspects of the socioeconomic environment, and strategic politics for economic growth. Urbanism and, more broadly, real estate development—including speculation and construction—became key strategies for capital accumulation and growth [17,18].

In contrast, neoliberalism advocates minimal government intervention in social, economic, and investment functions, promoting the private sector and free markets [19,20,21]. This philosophy emerged in response to the crisis of Keynesianism around the 1980s and was promoted through Thatcherism and Reaganism. The Bretton Woods Institutions, such as the IMF, World Bank (WB) and WTO, aided in spreading it across many countries, especially in the Third World, through structural adjustments and fiscal austerity programs involving the regulation of global finance and trade [22,23]. The assumption of neoliberal theory—‘a rising tide lifts all boats or trickles down’—posits that alleviating poverty can be most effectively achieved through the mechanisms of free markets and free trade [21]. Despite this, its dispossessory aspects, often termed ‘accumulation by dispossession’, describe how neoliberal state policies tied to urban modernization displace marginalized communities, transforming their small-scale properties into opportunities for elite capital accumulation [21,24]. The 1997 financial crisis prompted East Asian countries to adopt a more balanced and resilient economic structure to stabilize the financial sector and restore investor confidence. Speculative real estate remained important in attracting global capital, emphasizing supportive liberal policies alongside stricter financial and regulatory frameworks while prioritizing investments in infrastructure-driven urban development, such as public infrastructure—roads and transport, industrial zones, and affordable housing projects. This paradigm shift is characterized by the amalgamation of neoliberalism and developmentalism, which is termed ‘neoliberal developmentalism’ by Heo [1]. It underscores the neoliberal vision of a minimalist state while recognizing the state’s role as a critical component and supporter [12,14].

Sri Lanka was the first country in South Asia to adopt neoliberal policies in 1977 under President Jayawardene’s elite-driven right-wing government. According to Lakshman [25], this led the country to become a test site for neoliberalism in the Global South at the advice of the IMF and the WB. Subsequent regimes followed the same ideology, but governmental instability was consistently challenged by the impediments caused by the war and the welfarist ideologies of leftist political tensions [26]. However, after the war victory in 2009, the Rajapaksa regime positioned itself for strong political stability by co-opting all opposition forces, making them part of the coalition and consolidating the economy toward neoliberal policies. However, Athukorala and Jayasuriya [27] argue that his economic ideology significantly differs from the neoliberal tendencies of the previous thirty years. Instead, it exhibits Rajapaksa’s nationalist and populist political ideologies, notably centralizing power at the state level in an attempt to revert to a dictatorship and altering neoliberal policies guided by strong political and governmental intervention, similar to the East Asian model of “neoliberal developmentalism” that legitimizes authoritarian governance [28]. Despite contradictions and doubts about its applicability to the Sri Lankan context, we use the concept of “neoliberal developmentalism” in our framework not to imply a full realization of East Asian-style outcomes but to capture the postwar Sri Lankan government’s aspirational alignment with those models. This framing helps explain the state’s emphasis on aesthetics, speculative urbanism, and top-down control—despite its weak institutional capacity and financial returns.

In contextualizing ‘neoliberal developmentalism’ within the framework of postwar Colombo’s ‘world-class city’ development, we connect it to ‘neopatrimonialism’, as articulated by Shmuel Eisenstadt [10], a concept widely used to explain contemporary African politics and rooted in Weber’s understanding of power dynamics [29,30,31]. According to Weber [31], power is the ability to exercise one’s will over others [32]. This includes patrimonialism—a form of political legitimation and domination in which the ruler governs all powers legitimately and utilizes the institutions of the state to dispense patronage to followers [31,33,34,35]. However, to Roth [36], Weber’s patrimonialism is mostly absent; instead, he describes ‘modern patrimonialism’ as ‘personal rulership’, where political authority relies on the informal distribution of state resources by the patron in exchange for loyalty from lower-level bureaucrats operating on a client-patron basis [34,37,38].

To distinguish Weber’s traditional patrimonialism from contemporary political systems, Eisenstadt [10] introduced the concept of “neopatrimonialism.” This concept represents a shift towards a more bureaucratic and party-oriented form of patronage characterized by trends towards authoritarianism, co-optation, factionalism, clientelism, and elitist policies. Clapham [39] defines neopatrimonialism as “an organization where patrimonial relationships dominate a political and administrative system that is apparently rational-legal. Officials in bureaucratic roles possess formally defined powers, which they often use not for public service but as private property” [39] (Cf.: p. 48). To provide clarity, we adopt Erdmann and Engel’s [37] definition, which defines ‘neopatrimonialism’ as a blend of patrimonial and legal-rational rule, where political and administrative decisions partly adhere to legal-rational or formal rules and partly to patrimonial or informal ones [37]. The prefix ‘neo’ and terms like ‘mix’ and ‘partly’ emphasize the departure from traditional patrimonialism, describing a state where patrimonial and legal-rational bureaucracies coexist and operate simultaneously [37,40].

For nearly 76 years of Sri Lanka’s post-colonial political history, governmentality has been stabilized by family politics—a few families from the upper middle class and the elite. This has resulted in a centralized and authoritarian system that has been constitutionally institutionalized [41,42]. Wickramasinghe [43] notes that Rajapaksa centralized key ministries under family control, appointing siblings—including Gotabaya as Secretary of the MoD&UD—and placing over 40 family members in senior positions, enabling them to control nearly half of the national budget [44]. These political shifts highlight elite traditions of ‘neopatrimonialism’, which legitimizes centralization of power, nepotism, familial politics, clientelism, corruption, and challenges related to transparency and accountability, undermining the regime’s legitimacy [27,45]. The Colombo case offers how urban planning was implemented through a militarized governance structure that combined centralized political authority with command-driven project execution—an uncommon but increasingly visible characteristic of authoritarian redevelopment models in the Global South. We examine Colombo’s postwar ‘world-class city’ initiative within this political and economic context.

The Rajapaksa’s politics of militaristic authoritarianism driven by elite order partial bureaucracies called for the military to assist in implementing Colombo’s ’world-class city’ initiative along with civilian institutions. This form of neo-patrimonial characteristics draws inspiration from Riggs’s [46] depiction of ‘bureaucratic polity’ as a form of governance dominated by a military and civil service elite [47] and operates as its own decision-maker, shaping and enforcing its societal role without external regulation or oversight [36,48,49,50]. Although Colombo’s civil-military hybrid model is specific—particularly in its formal delegation of public housing to a military-led ministry—it reflects broader global patterns of expanding military roles in governance and civilian affairs. Scholars such as Siddiqa [51], Graham [52], Huntington [53], and Finer [54] have examined how militaries extend their influence into political, economic, and developmental spheres—often through institutional arrangements that blur the boundaries between security and governance. Comparative examples include Turkey, where the military enjoys high public trust while informally shaping state policy [55,56], and Indonesia under Soeharto, where loyalty was secured by granting military-political and economic privileges [57]. In Pakistan, Siddiqa’s [51] concept of “Milibus” describes the military as both enforcer and stakeholder in civilian domains. These global cases help contextualize Colombo’s urban militarization within a transnational pattern of authoritarian planning logic embedded in developmentalist states. Additionally, drawing from elitist theorists, Mills [58] examines the ‘power elite’—military, industry, and politics—in postwar American society, revealing that power is perceived as the accumulated capital of an elite group controlling critical aspects of society through personal connections [33].

We aimed to contextualize ‘neoliberal neopatrimonial developmentalism’ in world-class urban development, combining it with Soja’s [11,59,60] emphasis on spatial justice, integrating both outcome- and process-oriented justice in urban regeneration, and examining how institutions, policies, and practices shape spatial organization, particularly in spatially conscious politics and people’s interactions [61,62]. Spatial justice is not used here as a peripheral moral claim but as an analytical category that allows us to understand how militarized governance impacts access, rights, and equity—especially in contexts of forced relocation. This framing enables us to assess not only what has been achieved but also how it has been carried out and who it impacts, thereby clarifying the procedural and distributive dimensions of urban inequality. This expansion convinced us of the need to better understand the complex dynamics of power politics, planning policy, and equity in developing world-class cities and their implications for urban public housing projects. Focusing on Lefebvre’s [63] notion of social space and Soja’s [11] concept of ‘conceived space’, we examine how spaces are shaped by political agendas, policies, power dynamics, and interests. Building on Soja [11] and Lefebvre [63], we investigate how ‘conceived space’—shaped by elite political logic—conceals the lived experiences and relational attachments of displaced urban communities. This approach highlights the role of conceived space as a tool for spatial organization that often overlooks the lived experiences of residents [59,61,63].

According to Chiodelli and Scavuzzo [64], spatial planning, like ‘world-class’ urban regeneration, is inherently a governmental function always developed within a process influenced by politics and elite decisions embedded with substantive and procedural strategic political dimensions [64,65,66]. He further argues that planning translates political power decisions into territorial realities, positioning planners as technical agents of political will. Flyvbjerg [67] supports this view, stating that planners are not impartial agents of societal change but are instead civil servants or employees of political or elite interest groups, serving the interests of those who pay them. These ideas relate to the role of political power and bureaucratic governance in city development in the Global South, particularly in Sri Lanka, where planning is closely aligned with political authority. Within these backgrounds, to contextualize the military-assisted public housing program within postwar Colombo’s ‘world-class city’ initiative and understand it through ambitious political and elite motivations, we framed our study within the theoretical constructs of East Asian ‘neoliberal developmentalism’, incorporating concepts of ‘neopatrimonialism’ and ‘spatial justice.’

3. Materials and Methods

This qualitative study analyzes the discourse surrounding postwar public housing in Sri Lanka. It is based on the idea that human experiences and argumentative discussions, relying on claims and their support, play a crucial role in constructing meaningful discourse. The concept of discourse is complex and has many meanings [9]. In urban planning, discourse can hardly be captured solely through linguistic or content analyses that focus on textual patterns. According to Kumar [9], discourse is a higher-order construct that subsumes multiple arguments and argumentative threads. It includes diverse interactions among individuals, such as conversations and debates conducted through language—written or spoken—within a specific setting and towards a certain end [9,68]. Thus, discourse represents a broader exchange of ideas and viewpoints among various individuals in a particular situation. Conversely, an argument, as defined by van Eemeren et al. [69], is a reasoning activity concerning a specific proposition. Each argument has a distinct intent: to inform, confront, support, or persuade [9].

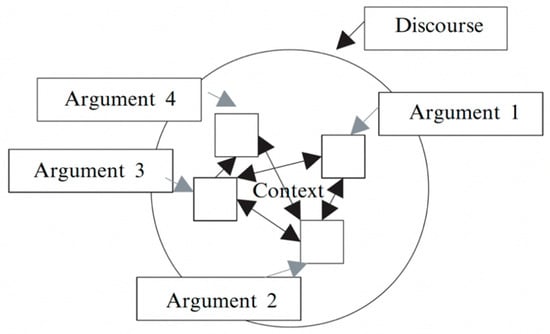

In this discourse analysis, we draw inspiration from argument-based models by Toulmin [70], Gasper and George [71] and especially Kumar and Pallathucheril’s [9] contextual model, portraying discourse as a constellation of arguments (see Figure 1). These frameworks are employed systematically to classify each argument into its components—claim (C), grounds (G), warrants (W), and, where relevant, backings, qualifiers, and rebuttals. This structure provides a basis for understanding how urban planners and decision-makers rationalize their choices within institutional settings. According to Kumar’s [9] model, understanding the contextual nature of discourse requires recognizing the setting in which it occurs, the communicative and social roles of participants, the norms and values, and any institutional or organizational structures [9].

Figure 1.

Discourse as a constellation of arguments within a context.

This paper is based on semi-structured interviews conducted with ten higher-ranked government officials, including seven urban planners and three military officers involved in Colombo’s postwar public housing program. According to Clark [72], qualitative research is deeply a personal enterprise; therefore, the selection of participants in this study is followed through personal relationships. To enhance data quality, a semi-structured interview guide [73] was developed and used during interviews. The open-ended questions explored participants’ experiences and perceptions of the public housing program, focusing on the influence of postwar politics and new institutional arrangements, including the role of military involvement in postwar development. Hints were used to broaden the discussion, capturing a wider range of professional perspectives.

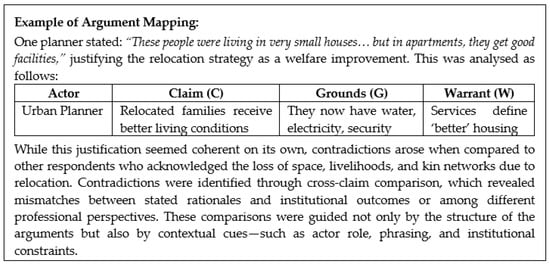

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Each transcript was systematically analyzed (Figure 2) to extract arguments by identifying claims, grounds, warrants, and, where appropriate, qualifiers or rebuttals. A claim is a statement or proposition that the interviewer would like the audience to believe [9]. It can take the form of a factual claim (true or false), a value claim (judgment or morality of something), or a policy claim (advocating a course of action). However, it is the central idea that the interviewer presents as his claim. Supports, on the other hand, are reasons and evidence that an interviewer provides to justify or defend the claim. They can be grounds (the basis for why the claim is true or valid), warrants (reasoning or logic—why the audience should accept the claim), backings (evidence that reinforces the warrants), qualifiers (modifiers that indicate the degree of reliance on or scope of generalization of the claim), and rebuttals (possible exceptions to the conditions under which a claim holds).

Figure 2.

Example of argument mapping.

The claims, along with their relevant supports, were extracted from each transcript. Then, an argument table—including 19 claims, with duplicates excluded (see Appendix A)—was prepared to allow a comparison of reasoning structures across actors. These elements were then reviewed for internal coherence and contextual consistency. When elements were implied rather than explicitly stated, we drew on Kumar and Pallathucheril’s [9] recommendations for interpreting context, the roles of actors, and normative expectations. This included instances where qualifiers or rebuttals were absent but could be inferred through tone, institutional framing, or comparison with policy documents and field experiences. The table helped us better understand how arguments clustered thematically and how claims supported, contradicted, or implicitly challenged each other across different actors. This comparative method enabled the tracking of emerging discourse patterns while remaining grounded in specific institutional logic.

The refined claims were then used to construct the thematic discourse within two primary domains. These themes did not arise a priori but emerged naturally from the experiences gathered during interviews and were supported by cross-claim patterns. They also reflected insights gathered during informal field visits to three relocation sites—Wanathamulla, Dematagoda, and Mattakkuliya—and were informed by discussions with urban planners and military officials in Colombo during July and August 2023. The findings section provides a detailed description of these themes.

4. Findings

Using the compiled argument table (see attached Appendix A) alongside the related crossclaims, we constructed our interview findings under two central themes: Theme 1, Civil-Military Governance and Political Control in Colombo’s Urban Transformation, and Theme 2, Elite Rationalities, Housing Strategies, and Socio-Spatial Consequences in the ‘Slum-Free’ Mission. These themes collectively illustrate how the postwar government implemented Colombo’s regeneration through a centralized civil-military governance system shaped by urgency, elite influence, and institutional loyalty. While Theme 1 focuses on the political logic and institutional framework that facilitated this hybrid model, Theme 2 examines how this planning strategy translated into the relocation and rehousing of Colombo’s underserved communities. Accordingly, the findings provide a comprehensive narrative of the program through the lens of institutional governance, speculative urban development, and spatial justice.

4.1. Civil-Military Governance and Political Control in Colombo’s Urban Transformation

This section begins with a contextual overview derived from the literature to initiate our discussion. It is followed by interview findings on establishing the new institutional arrangement, MoD&UD, to develop Colombo as a ‘world-class city’ and to understand the political motives of the Rajapaksa government after the war. Based on this, we explain the military’s specific role in the URP, its interaction with the UDA, and its subsequent impacts. These findings demonstrate that military integration was part of a broader civil-military institutional framework that supported the regime’s centralized and loyalist governance strategy.

4.1.1. Political Imperative of Military Integration

Transforming Colombo into a world-class city was proclaimed in President Rajapaksa’s political vision, ‘Mahinda Chintana Idiri Dekma: 2009’ (‘Mahinda’s Vision for the Future: 2009’), to make Sri Lanka the “Wonder of Asia” after the war. His political manifesto targeted an 8 percent GDP growth and an increase in the investment-to-GDP ratio to 32–38 percent over ten years to attract investments [74]. Rajapaksa’s strategy for Colombo was influenced by successful speculative cities like Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai, and Shanghai [75,76,77]. Transforming underutilized urban land and beautifying the city to attract foreign investments were presented as a national priority. The MoD&UD, formed by merging the military and the UDA, was tasked with relocating underserved families to high-rise apartments. While the merger was commonly justified as a means to utilize idle military resources, our findings, however, reveal that military involvement was part of a broader political strategy: a governance system that combined authoritarian command cultures with neopatrimonial loyalty networks. This approach strategically integrated military personnel into civilian institutions to enforce compliance, enhance efficiency, and maintain control.

- Capitalize on the Military’s Reputation for Urgency and Bypass Procedures

Several respondents claimed the MoD&UD was a political strategy to leverage the military’s strengths beyond just financial, instrumental, and labor. These include:

- -

- To leverage the strong reputation the military earned

Respondents noted that the military’s disciplined reputation, solidified during its decisive role in ending the war, became a powerful asset for the postwar government. This victory strengthened public confidence in the military’s capabilities and reduced societal resistance to its involvement in non-military tasks, as people believed that the military would deliver tangible results, drawing parallels between its wartime achievements and its potential to manage postwar development. The government capitalized on this sentiment, positioning the military as a driver of urban transformation that might otherwise have stalled due to bureaucratic hurdles.

“Right after the war, Defence Secretary hurried to develop Colombo and wanted military to team up with UDA…they felt it was a smart move.”

A widespread media campaign celebrated military personnel as national heroes, especially Gotabaya, while positioning the military as a catalyst for progress. In this way, the military’s symbolic capital was integrated into a broader strategy that encouraged cooperation and minimized conflict, allowing civil institutions to embrace a culture of order rather than one focused solely on deliberation.

- -

- To Act Urgently and Bypass Procedures

Respondents claimed that the postwar government used the military to bypass bureaucratic procedures through its “military method.” For them, “military method” means that the military can perform certain actions, interpreting them as crucial for national security or public safety. These urgent actions required other institutions to bypass protocols, or the military would override them.

“Government wanted to make Colombo like Singapore. They wanted it fast, control people’s resistance and skip formal UDA procedure. With this military method, it’s just all about national security…military doesn’t care about procedures or mistakes; they just want to keep things moving. That’s why they put UDA under the Defense Ministry.”

The respondents believed that bypassing procedures was not a military requirement but a political strategy to expedite things quickly. After the war ended, the government aimed to accelerate development while ironically bypassing its own procedures. They claimed that the government strategically used the military’s legacy and command-driven culture to achieve political targets that were outlawed.

“When military gets orders, they don’t question, they follow. If told to demolish, they do it right away without hesitation.”

Respondents claimed that this military culture, effective communication, and excessive influence over civil officers allowed the government to utilize them effectively while satisfying officers by giving them key roles and reinforcing their perception as essential actors in national reconstruction. However, some respondents criticized the government’s unnecessary urgency, which overshadowed numerous mistakes.

- Keep the Military Loyal and Control Under the Government

Some respondents claimed that the government’s primary intention after the war was to keep the military loyal and under control by assigning alternative tasks and offering privileges, thereby preventing any riots against the elected government.

“What can we do with military after the war? We don’t know what they’ll do or which side they’ll take …”

They indicated that Gotabaya leveraged his close military ties as a former officer, rewarding military personnel with high-ranking positions.

“When a military officer became a ministry secretary, it was his duty to reward military. So, he appointed them to various top government positions, including the UDA.”

- Building Trusted Go-Getters

Respondents stated that the government, particularly Gotabaya, needed a trustworthy team—proactive and ambitious—to achieve the government’s goals. They suspect Gotabaya trusted the military more than government officers.

“They [Gotabaya and his clan] thought military could handle things better than us. Maybe they didn’t trust us to get the job done right.”

Respondents further explained that during the early postwar period, President Rajapaksa and the Defense Secretary, Gotabaya, genuinely wanted to make a significant development in the country, although this was later politicized. They aimed to prevent corruption and misconduct in the bureaucratic administrative system by using trusted military personnel with whom they had worked during the war. Additionally, they suggested that loyalists who supported the regime during the conflict were rewarded with prestigious roles after the war, such as key positions within the UDA and other influential agencies, further solidifying the government’s control and maintaining political stability.

“So, like, I heard that the ex-UDA minister had some serious corruption issues. The President wanted to put a stop to it. And since the military wasn’t doing much after the war, he decided to hand UDA to the Defence Ministry.”

Respondents highlighted that establishing the MoD&UD and placing it under Gotabaya, the president’s brother, was a strategic political move to maintain control the military and the UDA. They also saw this as a way to keep trusted loyalists in power, ensuring their continued allegiance while addressing inefficiencies. They considered this merger a timely step to reform the UDA, which had become inefficient despite its past successes. In this way, the military functioned both as a political partner and a bureaucratic tool, mobilized to ensure effective governance.

4.1.2. Military’s Role in the UDA and the URP

Colombo’s slum-free mission, known as the URP, was under the UDA’s responsibility. However, it functioned as a privileged entity with additional benefits like staff allowances and priorities. Moreover, it was rated higher than other departments, likely because it was closely associated with powerful politicians, including the Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the President. This close association may have elevated its standing within the government, giving it more authority and resources than other departments.

Nevertheless, the military’s role within the URP is unclear in the ongoing discussion about public housing in post-war Colombo. Scholarly literature critiques claims of military involvement in demolishing but lacks an explanation of its overall involvement. Our findings revealed a layered institutional role for the military. While it may be less visible than many assume, its presence is deeply woven into a system of centralized executive control.

Participants revealed that the military’s involvement occurred across three administrative tiers, illustrating a layered approach to integration—where the military plays roles at various levels, from symbolic leadership to operational support, all within the framework of civil-military urban governance. These tiers are: First, figures like Gotabaya, his associates, and the MoD&UD were involved in political and elite decision-making. Second, high-ranking military officers and politically appointed civil servants at the UDA and their preferred staff were involved. Third, external military battalions were occasionally summoned for specific tasks, like providing backup support during demolitions.

Tier 1: According to respondents, Secretary Gotabaya was the key figure in controlling the functions of the ‘world-class city’ transformation. He was the chief administrator, planner, and architect of all its decisions. They emphasized that Gotabaya’s military background—command-driven, top-down, dominantly dictating and overseeing culture—significantly influenced the implementation and progression of the program.

“Every two weeks, Defense Secretary gives us instructions. He is checking things out every morning…if he spots something that needs development, he wants us to start right away….it was that urgent. His influence was huge from the start, and honestly, officers didn’t get to discuss things with him. We wouldn’t have done these projects without him.”

Respondents appreciated the initial phase of Gotabaya’s administration, highlighting that it enabled the rapid execution of the URP. They noted that while centralized control was efficient in some respects, it gradually shifted focus toward political votes and electoral objectives. This change resulted in a corrupt and politicized system over time, which polluted his later politically driven interventions through his close circle of associates. These interventions generated immense urgency, leading to several mistakes that will be discussed later in this section.

“He [Gotabaya] ended the war as he had good administration…. Eventually, all systems got politicized and corrupted.”

We identify Tier 1 as the epicenter of symbolic and institutional military leadership, where planning and politics merged under the strategy of command governance.

Tier 2: Respondents highlighted that the integration of the military into UDA resulted in significant changes in its management. They stated that high-ranking military officials, including two brigadiers, directly reported to Gotabaya and the MoD&UD, despite holding top positions within the UDA. This resulted in UDA management following their decisions without question. Furthermore, external individuals were brought in and placed at various management levels, bypassing recruitment protocols and making them loyal to the MoD&UD. Consequently, URP was established as a distinct entity and a prominent project within UDA, appointing one of the brigadiers as the chief project director.

Military officers acknowledged that they directly reported to Secretary Gotabaya and the MoD&UD while housed in the UDA. They emphasized that they were part of the military, not the UDA, despite holding top positions and participating in UDA projects with their battalions.

“We reported directly to him. UDA managed only our clerical stuff, but all the real decisions and priorities came from him and the MoD.”

They also accepted that they brought trusted military officers to work in the UDA, thereby expanding the military presence.

“UDA Act is very powerful, so we added some force and speed. Honestly, at first, we didn’t trust UDA officers….we brought in some reliable military officers who had worked with us. Later, as they saw how we operated, many UDA officers joined us”.

This narrative illustrates how trust and loyalty often took precedence over formal recruitment processes. It demonstrates how these wartime networks became an essential part of the postwar institutional systems. However, some respondents argued that involving the military in a civil institution was problematic.

“Bringing in military folks to oversee UDA people? That’s not a good idea. It was tough to coordinate with them; their strict ‘follow orders’ not fit into us…”

Most respondents argued that the military’s “order and command culture” and inexperience in social aspects—particularly in dealing with people and understanding their socio-economic needs—negatively affected the project’s relocation process.

“The big issue with this [URP] project was its military control. They didn’t get the social side enough.”

These critiques indicated a notable mismatch between military discipline and the collaborative and community-focused aspects of civilian planning. However, the interview participants from the military argued opposingly to the above claims. They stated that their involvement was methodical and systematic, and they had adequate knowledge and experience in rehousing families in war zones. From their perspective, their contribution added both technical expertise and energy to the UDA, which many viewed as inefficient.

“UDA was like a sleeping elephant—once we teamed up, they got things rolling. We showed them how to work smarter and faster…”

Despite some challenges, many respondents appreciated the military’s role in the UDA and URP. First, the UDA’s prominence increased through its merger with the MoD&UD, a major ministry led by the president’s brother. Second, after years of financial constraints, the UDA had the opportunity to engage in significant projects in Colombo, including public housing, which were not directly within its scope. Third, under the MoD&UD, the UDA acquired prime lands in Colombo, expanding its assets. We observed Tier 2 as the functional core of civil-military integration, where the governance of public housing has shifted from conventional planning to an accelerated delivery system driven by command hierarchies.

Tier 3: The respondents acknowledged that the military was present in the URP’s operational activities during the demolition and relocation events. They stated that the URP found it necessary to deploy external military battalions as backup support to assist UDA officers and the police in unauthorized demolitions.

“Yeah, there was some military help, but they weren’t actually doing the demolishing. They just supported the police and UDA officers in the early stages of projects like 54 Waththa, 66 Waththa, and Wanathamulla. After the government changed in 2015, they were completely out of it.”

Respondents indicated that in any slum or shanty relocation, there is usually initial resistance from underserved communities, even if they are unauthorized. While the UDA had legal authority and police support, limited military backup was occasionally used to manage resistance, primarily during the early stages of the URP due to community distrust and a lack of awareness about the URP and its secure relocation. The military’s involvement was not part of regular practice but was deployed during critical, highly sensitive moments to support order and minimize opposition, claiming that their support was advantageous to the UDA and URP in difficult times when relocation faced resistance.

“They just handled operations, not planning or design. At that time, their operational involvement was helpful in moving unauthorized. They had a good reputation among the people.”

Respondents rejected criticisms of the military’s role in forcibly demolishing slums and shanties, describing their involvement as a “backup force” in UDA and URP. A military respondent explained that they acted as backups, using their reputation and uniforms to build community trust for safe relocation. He noted that UDA and URP struggled due to a history of broken promises.

“When we went into Wanathamulla to clear some land, it felt like a battlefield. They didn’t trust UDA’s promises. But they believed us, not me, but my uniform.”

This comment highlights how the military’s symbolic authority, rather than its force, played a key role in easing public resistance.

Respondents rejected the criticisms of military force. They noted that the UDA has the legal authority to demolish unauthorized structures with police support. Thus, military assistance was only used in critical cases, like the Slave-Island project.

“We don’t need the military—We have the power…. We have never used military for evictions; we do relocations legally.”

One respondent clarified this with a strong argument, proving that the military has not been involved in the demolitions or relocation activities.

“So back in 2015, “yahapalanaya” government set up a commission…. They looked into people’s complaints and checked out military involvement but found nothing. Turns out, it was just a media rumor…”

Although the military has denied any direct involvement in the demolition, their presence in the surrounding area during relocation efforts—with uniforms, patrols, and an air of authority—contributed to the perception of a militarized space.

During the interviews, we observed that two brigadiers, including the head of the URP and their subordinate military officers, wore uniforms and maintained a visible military presence, even though they were not directly involved in demolitions or relocations. Additionally, the URP was led by a brigadier who personally visited underserved settlements in uniform, distributing notices, further signaling the military’s involvement in the relocation process in these communities. These developments challenge the existing literature, which typically describes the military’s role as primarily forceful or repressive. Instead, the findings indicate that military involvement was more systemic, intentional, and visually expressive, functioning at the intersection of governance, discipline, and a sense of symbolic reassurance.

We identify Tier 3 as the area where the military’s presence was publicly showcased. The three-tier representation, based on participant discussions, shows that the military’s role in the UDA and URP went beyond enforcing demolitions, as commonly understood. This role involved a unique blend of symbolic authority, structural placement, and timely support—working together within a broader civil-military governance system. The MoD&UD emphasized this integration, merging military capabilities with political and elite influences to manage urban transformation with speed, control, and symbolic legitimacy. These findings collectively reveal a governance model that redefined housing delivery in Colombo as an extension of postwar centralized planning.

4.2. Elite Rationalities, Housing Strategies, and Socio-Spatial Consequences in the ‘Slum-Free’ Mission

While the previous section focused on institutional arrangements, this section shifts to how elite values and perceptions shaped public housing outcomes under the URP. It focuses on the socio-spatial dimensions of Colombo’s ‘world-class’ development. We begin with elite perceptions of underserved communities, followed by two subthemes: housing strategies linked to the ‘slum-free’ mission and the associated challenges.

4.2.1. The Elitist Perception of Underserved Communities

Our conversations revealed significant contrasts in how political and elite groups perceived settlers in slums and shanty communities in Colombo. These perspectives were central to understanding the URP led by the UDA, and they also influenced how the program defined legitimacy, framed relocation, and justified large-scale urban clearance.

One respondent, reflecting class-based attitudes, expressed that cities are primarily designed for wealthy communities, while low-income residents should either leave the city or adapt to a different lifestyle. This perspective highlights the exclusionary characteristics adopted by planners over time as part of an elite group in city development.

“If you’re a planner, you serve the rich, not the poor…poor can’t afford to live in urban and enjoy its facilities. They have to leave the city, or live in a different way. Urban is always for the rich…. I’m not serving the poor—I serve the rich.”

This view framed shanty communities as unauthorized encroachments. The following quotes from a military officer and a planner describe the situation:

Military officer—“We saw unauthorized structures like people occupying government property. To me, it’s a crime, injustice.”

Planner—“Unauthorized is unauthorized. They use common utilities without paying…and were drug addicts”.

Despite this, some respondents acknowledged that underserved communities sustain Colombo’s economy. This informal, low-skilled workforce enables middle- and upper-class residents to stay comfortably in the city, highlighting the need to retain them.

“Although we were not much considered in development plans, these low-income people represent fifty percent of Colombo’s population. They are Colombo’s engine. They keep Colombo alive.”

“We wanted to keep these people in Colombo. Their contribution, especially for the informal sector, I mean labour like cleaning.”

This dual perspective in elite urban thinking—viewing underserved settlers as both encroachers and essential economic contributors—underscored their social and spatial inclusion within the city while simultaneously influencing the rhetoric surrounding relocation and its practical implementation. This next section clarifies these dynamics further, highlighting the social and spatial reasons behind the URP process.

4.2.2. Housing Strategies in World-Class ‘Slum-Free’ Mission

We revealed two distinct strategies in Colombo’s postwar ‘slum-free’ housing program. One strategy aimed to regenerate underutilized lands in prime areas adjacent to upscale commercial and financial developments. The second strategy focused on reclaiming government lands from unauthorized occupants, primarily shanty communities.

Regeneration of Privately Owned Prime Lands

This strategy focused on acquiring old slums and decayed urban areas, particularly near upscale commercial and financial developments in Colombo. These underutilized areas were prioritized for immediate regeneration despite legal complexities. Authorities believed their appearance hindered the city’s image and that regenerating these lands would be profitable. Accordingly, underserved settlements in prime areas—Slave-Island, Torrington, Borella, and Wellawatte—were targeted for relocation. The projects under this strategy began with agreements from private developers; therefore, the government was obligated to adhere to their conditions, especially the timelines.

According to discussions, the demolition of slum housing on Mews Street, Slave-Island, in May 2010, in support of the ‘Colombo Port City’ project—a flagship initiative with significant Chinese investment—fell under this strategy. Participants mentioned that Singapore’s model inspired the Rajapaksa government with its ‘world-class’ city-making approach, which viewed the real estate business as a key strategy for attracting foreign investment to drive economic growth.

“Right after the war, investors, mostly Chinese, came looking for projects—especially the Port-City. Others were interested in adjacent areas. So, the defence secretary suggested Slave-Island. It was a slum.”

For them, Slave-Island was not a shanty area; it was an old slum area characterized as urban blight. They claimed that these slums were eyesores that diminished the city’s desired world-class appearance and were underutilized; therefore, Defense Secretary Gotabaya wanted this area to be regenerated. They also noted that Slave-Island residents had some legal ownership despite the slum conditions.

“They were not encroachers…they had some legal rights…but still live like slum people.”

To respondents, although UDA had legal powers to take over private lands immediately without the consent of the owners, it should have followed the formal government procedures outlined in the Land Acquisition Act, which can be a lengthy process lasting years unless the owners accepted UDA’s compensation package. They stated that in the Slave-Island project, their ownership issues were complex as both owners and occupants claimed property rights, which UDA could not resolve quickly following Gotabaya’s urgent requirement. This compelled UDA to adopt an alternative method—forced eviction with military assistance. The approach taken involved seizing physical possession of the land immediately and temporarily relocating families by providing them with funds to rent housing independently.

To them, the Slave-Island project faced significant delays, largely due to disputes over property rights between landowners and occupants. These conflicts eventually escalated to the courts, extending the resolution process over several years. Although the physical clearing was completed and initial agreements with investors were in place to sell the land, the UDA could not provide clear land titles to investors because of the ongoing legal battles. Despite agreements assuring occupants that they would receive housing and commercial spaces equivalent to what they previously had, ownership disputes left many plans unfinished. Additionally, the project encountered resistance from the Colombo Municipality, which was governed by the UNP at the time, as well as reluctance from other infrastructure agencies. This created further setbacks in providing essential services like roads, drainage, electricity, and water despite agreements with the investors. As a result, the UDA had to bear the cost of renting temporary accommodations for the displaced occupants for many years, which added a considerable financial burden while the legal and design issues were being resolved. This situation contributed to the overall delay in the start of construction by the investors.

Our findings revealed that the Slave-Island regeneration project was a failed attempt at postwar Colombo’s land development and housing initiatives. Although the strategy aimed to enhance real estate value and attract foreign investment, these neoliberal objectives were never achieved. Instead, land clearance proceeded without legal resolution, investor interest diminished, and the promised economic returns failed to materialize. This case highlights the limitations of speculative urbanism in a context where legal complexities, centralized governance, and political urgency dominate market logic. According to interview participants, the postwar government and the UDA quickly distanced themselves from this strategy, halting the development of privately owned underserved lands due to the above challenges in implementation. The Slave-Island project was reported as the first and last large-scale initiative of its kind.

Reclaiming Encroached Government Lands

The second strategy aimed at reclaiming government lands from unauthorized occupants, popularly called encroachers or shanty communities. These residents lacked rights or ownership over the land they occupied and thus had no negotiating power or input on relocation decisions. The UDA decided where, when, and how they would be relocated—on or off-site, temporarily until construction or permanently—based on housing availability.

- -

- The Target

According to respondents, a key constraint in making Colombo a world-class was the fragmentation of small, underserved communities. Some settlements were located in Torrington, Kollupitiya, and Thimbirigasyaya, which were designated as elite areas, as well as in Borella and Narahenpita, popular areas for high-middle-income residents. Most of these settlements were not simply encroached; rather, they had been created by authorities like the UDA and NHDA to temporarily house people displaced by earlier land takeovers. Many had been resettled multiple times with promises of legal housing, yet they were labeled unauthorized due to original encroachments. Consequently, none of the authorities were willing to grant them legal titles to the places they lived.

“The government couldn’t develop the city with people at every junction—Colombo 07, Borella, Narahenpita, Kollupitiya…need for a solution.”

“Those were our early resettlement sites. In Premadasa’s time, people were given one or two perches. When “Summit Flats” was built, many families were relocated to “Summit Waththa”. Same with “Keththarama”, those people were moved to “Apple Waththa”.”

Although many reports cited 68,812 households in 1499 settlements, the URP aimed to build only 50,000 units, prioritizing 40,000, as the rest could still be utilized.

“They said 68,000 families, but we found 56,000. Our survey showed 40,000 slums and shanties. So, we planned for 50,000 units.”

- -

- The Strategy

The URP identified that underserved settlements occupy 900 acres. The plan was to resettle them in high-rises using 350 acres, allocate 100 acres for open spaces and sell 450 acres for profit. Respondents indicated that URP had a simple formula to evaluate the financial feasibility of the project aimed at freeing up 450 acres to sell from 900 acres.

“We thought, why not give encroachers new houses and reclaim prime land to sell? We figured if we give one new house to a family, we could get at least two perches. Those two perches worth millions [SLR] in Colombo—like 2 million per perch. So, we’d use a quarter of the land for the new house and sell off three-quarters to investors. We also charge one million for each new house. That way, we’re pocketing at least 2 million in profit. With this formula, the government doesn’t need to spend much, and the families get new houses.”

This approach framed housing as a self-financing entity—linking relocation to the extraction value of real estate. However, as we will explore in the later sections, these assumptions were excessively optimistic: land values were overestimated, investor interest was not as strong, and repayments from relocated families didn’t meet expected amounts, highlighting the shortcomings of a market-oriented planning model.

To them, URP was initiated by issuing bank debentures and raising SLR 10 billion. The money earned from selling liberated lands was assumed to be sufficient to repay the debenture capital. Additionally, compared to the previous strategy involving privately owned lands, reclaiming government lands by evacuating encroached occupants proved to be more lucrative and faster. The effectiveness of this strategy was that the UDA could quickly evict the occupants and bring those lands to the market for sale since most of these communities occupied government-owned lands. Furthermore, the UDA required minimal force, as it held full legal authority under the UDA Act.

According to respondents, the cleared value of the land was critical to consider as most of the encroached settlements (shanties) were low-lying lands. Hence, the project followed a distinct process to prioritize resettlement. The considered factors included land saleability, location, and the number of relocations against the extent of reclaimable land.

“We gave priority to lands we can sell out quickly,”

Therefore, the needs of those living in severely substandard settlements or those requiring immediate housing were not considered a priority.

- -

- Process of Relocation

According to respondents, UDA’s approach left no chance for underserved residents to oppose it. Everyone was considered unauthorized despite documents like utility bills, CMC letters or electoral records. However, at least one of these could be useful for inclusion in the selectees list.

“There were no choices. Why do they need choices? We said you’re unauthorized and explained we could take their lands legally. If they agreed, they would get a relocation house.”

Respondents reported that one new house was provided for every demolished unit, excluding extended families. House conditions like size, floors, materials or facilities were not considered. They noted that the URP’s new apartments were similar, featuring a living area, one room, a kitchen, and a toilet. Phase I apartments during the Rajapaksa regime were mostly 450 sqft, later increased to 550 sqft in Phase II under the “yahapalanaya” period. They argued that the house size was reasonable compared to the residents’ old houses and was based on construction costs. They also mentioned no global standard exists for house size or facilities, justifying their decision.

“We decided 450 sq. ft. based on costs. The other reason was most had lived in less than this in their whole life. We later increased this to 550 sq. ft. However, we had to proceed with the 450 sq. ft. for the first stage of the 5000 houses, as we had already granted contracts. Another thing is that nowhere I mean, NIRP or any other international policy, has a rule specifying 550 sq. ft. It depends on country to country. For example, in Mumbai in India, they use 275 sq. ft.”

Respondents indicated that, although the relocation process was strict, some grievances were limitedly considered by a committee appointed to review grievances. This was mainly because some families, about 10 percent, had two or three floors in their houses exceeding 700 sq. ft. and comparatively enjoyed good lifestyles, although they were unauthorized and categorized as exceptional cases. They were provided with one, two, or sometimes three additional houses. In these instances, both the size of their home and the land area were considered for qualification. Furthermore, families that could prove land ownership through documents such as conditional deeds issued by CMC or NHDA were deemed entitled to receive a free house during the relocation process. All others had to pay Rs. 1 million for the new apartment, which they could pay for in installments, in addition to water, electricity, and maintenance fees.

According to respondents, the relocation occurred in high-rise buildings, mostly 10 to 15 stories, on low-priced lands in the city’s northern and eastern edges, such as Wanathamulla, Dematagoda, Maligawaththa, Mattakkuliya, and Blumandhol, which were scandalously underserved settlement areas. Relocation began by demolishing settlements on the most valuable lands and resettling families in these high-rise apartments that did not fully comply with the NIRP guidelines. As a result, the families who lived in prestigious city areas moved to less desirable outskirts. However, depending on the availability of vacancies, they were given a limited chance to choose the good ones among these projects. However, it was not a surprise for the families who originally lived in those scandalous areas as their relocation was either on-site or adjacent.

“We targeted higher income. So, in the first stage, we relocated Narahenpita, Castle Street, Borella, Colpetty, Panchikawaththa, and Dematagoda, the most valued lands in Junctions. Yeah, we had to follow NIRP, but we made a few adjustments in our initial stage.”

Respondents stated that URP relocation was compulsory but almost voluntary. They denied media reports about military involvement in the relocation. They also condemned scholarly reports, mentioning that they generalized the Slave-Island case to all other relocations without understanding the two different strategies and the actual events. They acknowledged that military incidents occurred only in projects like Wanathamulla, 54 Waththa, and 66 Waththa, and happened only in the very early stages. They gave two reasons for these incidents. Firstly, at the beginning of the project, people—especially underserved communities with negative experiences from previous regimes and false promises—had doubts about the assurance of obtaining new houses and showed resistance. Secondly, within these communities, there were thugs, drug dealers, and political factions who represented less than 5 percent of the population but dominated the communities, encouraging others to resist the project for personal gain. They preferred to maintain these settlements for their underground businesses.

“You know, even though people were living in unauthorized settlements, they just wouldn’t move on their own. There was some real reluctance. Some guys in the community, like gangsters and drug dealers—maybe five percent—really didn’t like our relocation program and stirred up resistance. Yeah, there were times when the military got involved, but it wasn’t like we were forcing anyone out violently.”

In such situations, the military was deployed as a backup force to support the police and UDA officers in initiating demolitions, as the defense secretary, Gotabaya, was firm in his decisions, and they had to execute them without hesitation.

While they stated that the military had no role in demolitions throughout the project’s duration—a fact that society completely misinterpreted—they introduced a new argument to explain why society thought the military was involved in these relocations. For them, the project, in the early period and for a long duration, was headed by a uniformed Brigadier. He was the project director and had to be involved in every project activity. He had a guard of a few uniformed officers with weapons and was involved in distributing demolition orders along with the project staff who visited houses to convince settlers about the relocation and the conditions for them to adhere to. On the other hand, when people came to the project office with complaints and grievances, he was the officer in charge of the final decision. It appeared that the military was playing a leading role, and settlers were under emotional threat to react against or engage with URP officers coupled with uniformed military personnel. Furthermore, the lands, once cleared after demolishing unauthorized structures, were marked with a sign reading, “This land belongs to the Ministry of Defence and Urban Development”—a feared signal to the public that entering it would result in immediate imprisonment for acting against national security. During our conversations, we realized that this military involvement was capitalized by the URP project to minimize the reactions of the settlers.

4.2.3. Challenges and Drawbacks in URP

Our discussions revealed that the high-rise apartments constructed by URP failed to comply with their own UDA regulations and minimum building standards. These regulatory violations included inadequate parking, insufficient distances between buildings, and inadequate space for light and ventilation. As a result, these apartment buildings could not obtain approvals from the UDA planning department and the Condominium Management Authority (CMA). Ironically, these buildings are unauthorized under UDA law and not fit for occupation.

Respondents indicated that compliance with regulations was not a priority for URP; instead, the focus shifted to quickly clearing lands and constructing more housing units. One respondent stated that since these buildings were for low-income communities, regulations were not much considered.

“Low-income housing, means there are no regulations.”

After political pressure and influences from URP, a few buildings received UDA approvals, while CMA approvals remain pending. They stated that failure to obtain approvals led UDA to halt the granting of legal house titles to the relocated families.

“We weren’t worried about regulations. There was just so much pressure to get things done quickly! The higher-ups wanted fast results, and honestly, our team was just trying to please them. We mentioned the rules, but they weren’t interested. It was all about speed not consequences.”

Some respondents argued that giving homeownership would lead families to resell their units for substantial profit and build unauthorized homes elsewhere as they were accustomed to that lifestyle and wanted to avoid it.

“We hold these houses until their kids adjust. We know, after that, they won’t return to shanties.”

The discussions revealed that the CMA was not the only agency obstructing the URP. As Gotabaya’s brainchild, the URP had a dominant role not only within the UDA but also on a national level, sidelining collaboration with other key agencies such as the National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWS&DB), the Electricity Board (EB), the CMA, and notably, the Colombo Municipality. Even within UDA departments essential to the URP’s high-rise housing projects, collaboration was limited. These institutions frequently obstructed URP implementation, withholding support, particularly in the post-implementation phase, such as necessary approvals, maintenance, and ongoing collaboration. Lack of support forced UDA to spend millions of rupees on maintaining buildings and utilities, requiring them to employ their own officers.

Despite these drawbacks, the relocation initiatives failed to accommodate the social and cultural patterns of the underserved community. Some respondents who closely worked with resettled families shared their concerns about these communities. We noted that relocated families were unaccustomed to high-rise living, particularly regarding their children’s safety in tall buildings of 10 to 15 floors. The design of these apartments, sized between 350 sq. ft. and 450 sq. ft., presents numerous challenges, including limited space for dining, washing, and drying clothes, as well as privacy concerns due to the placement of doors and windows, which exposes private life to neighbors. Noise is also a significant issue, with sound easily passing between units, posing challenges for children studying at home. One respondent noted that the main focus of the URP was on releasing land, with little consideration for building size or height, neglecting social mobilization efforts to assist families in adapting to their new lifestyle in condominium-type apartments. Moreover, these large housing complexes, accommodating approximately 5000 to 6000 families, often lack essential community facilities such as playgrounds, daycares, and shops for daily needs. Remarkably, planners and military officers in our interviews acknowledged these issues as mistakes.

The land sale business in the URP faced significant challenges and was widely considered a failure for several reasons, according to the respondents. First, according to government protocols, the UDA must follow mandatory steps when selling land. Although it is called land selling, UDA could only offer long-term leases while retaining the power to reacquire it. Investors were reluctant to purchase land on lease terms, especially at market value, as this reflected the freehold value in the market. This reluctance stemmed from distrust of UDA’s politically influenced land reacquisitions. Second, the market value of the land was determined by the government chief valuer from a different ministry (Ministry of Finance), which did not align with the UDA’s land sale objectives. The UDA could not offer land below this government-set price, which was always considered high. Investors could purchase freehold land directly from private landowners at lower prices through brokers without strict government terms. Third, the UDA lacked a marketing strategy to attract global investors. This was beyond their expertise and outside the project’s scope. To them, URP managed to free up less than 150 acres, although it was initially planned to liberate 900 acres and allocate 450 acres for sale. Due to the failure of the land sale business, the UDA sold less than 40 acres, leaving 110 acres still available for sale. Accordingly, the financial feasibility assumptions that URP adopted to recover the capital invested from 10 billion state bank debentures did not work.

Additionally, many relocated families refused to make regular payments due to the URP’s failure to provide legal titles. This resulted in substantial outstanding payment arrears that the URP must now settle with the WS&DB and EB. According to a respondent,

“Honestly, we are utterly lost now. We couldn’t sell land and the 1 Mn [SLR] idea failed. We’re trapped in these houses, paying for water and electricity and also doing maintenance. But families don’t pay for those bills.”

These outcomes highlight the challenges of a planning model that placed a greater emphasis on speed, land recovery, and physical delivery over legal, social, and institutional coordination. Although the URP was initially designed to promote real estate profitability and financial independence, it failed to achieve its investment objectives, generate sufficient land sales, or recover housing costs from relocated residents. Rather than functioning as a market-based model, it transformed into a state-subsidized framework facing difficulties due to ongoing ownership disputes, regulatory issues, and a lack of collaboration among agencies.

5. Discussion

We realized that understanding postwar public housing in Sri Lanka requires examining the complex interplay between government politics, aspirations for a world-class city, and military involvement. This section contextualizes these interplays in light of our findings, situating them within the broader theoretical framework of urban planning, spatial justice, and governance. Instead of thematically repeating each finding, the discussion highlights four key dimensions that help explain how public housing in Colombo was influenced by the principles of centralization, elite dominance, and speculative urbanism. These include (1) the political motivations and development approach behind the ‘world-class’ city transformation; (2) the shifting perceptions of urban space and social exclusion in Colombo; (3) the integration of the military into civil governance; and (4) the implications of these processes for public housing delivery and displacements. Together, these dimensions illustrate how tensions between authoritarian delivery models and the ideals of inclusive urban development influenced Colombo’s postwar housing strategy.

5.1. Political Motivations and Development Approach

Rajapaksa’s postwar campaign was driven by a combination of strategic, political, and personal motivations. He aimed to consolidate power and cement his legacy as a transformative leader by capitalizing on the public euphoria generated by his decisive leadership following the war. This reflected a hybrid governance model parallel to the East Asian model of neoliberal developmentalism [1], blending market-oriented strategies with strong state intervention that legitimizes authoritarian practices through the promise of rapid economic growth, emphasizing urbanism and real estate development as key drivers.

For Rajapaksa, transforming Colombo into a ‘world-class city’ was not just about economic modernization; it was a strategic political move to shape the country’s future. In emulating cities like Singapore, his administration aimed to establish a governance model supported by loyal military and civil elites to ensure political stability and safeguard—characteristics associated with Eisenstadt’s [10] notion of neopatrimonialism. At the same time, this aimed to deeply embed Rajapaksa’s ideals in society, suppress opposing views and secure his ideological dominance. This blend of authoritarian nationalism, grandiose leadership and market-oriented growth aligns with Weber’s [31] concept of charismatic domination, where a leader’s authority legitimizes broad state control over societal structures—bears noticeable similarities to the strongman political leadership styles like Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad and Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew [75,78]. This approach focused less on participatory planning and more on establishing a lasting political order based on elite consolidation and image-driven development.