1. Introduction

Since its publication by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) in 1997, the 802.11 wireless network standard has become increasingly popular in industry and for home use [

1]. Wireless networks have become essential to modern mining operations, enabling real-time monitoring, control, and communication among various equipment and systems.

However, wireless networks are vulnerable to issues such as signal interference, congestion, and attenuation, which can cause network downtime and disrupt mining operations [

2]. For instance, in the S11D complex—Vale’s (

https://vale.com/, accessed on 1 October 2025) largest iron ore mining project, located in Brazil’s Carajás region—wireless network failures significantly impacted productivity. In the third quarter of 2018, the complex increased its share of premium iron ore sales and reached 70% of its nominal production capacity, setting a quarterly record of 16.1 million tons [

3]. By the third quarter of 2019, production had grown by 26.1% year over year, reaching 20.354 million tons [

4]. Despite this growth, the same report noted that wireless network disruptions led to approximately 25 h of production stoppages in that quarter, resulting in an estimated loss of 395,000 tons of ore and USD 40 million in revenue, based on the average iron ore price of USD 103 per ton for that period [

5].

To address the downtime issues caused by wireless network problems, some frameworks measure packet loss rate, delay, and throughput to assess network quality and, hence, detect and diagnose network problems [

6,

7]. The data are often presented using Radio Environment Maps (REMs). However, the software often needs a laptop or smartphone to perform data acquisition, which is problematic for applications where access to the measurement location is restricted, as in the case of mining [

6,

8].

The concept of REM was introduced by Zhao et al. [

9] and consists of an integrated database that contains comprehensive information from various domains related to cognitive radios, including geographical features, available services, spectral regulations, locations, and activities of radio devices, as well as policies and past experiences. The principal feature is to store information to be queried by intelligent entities that can interpret it.

Several interpolation techniques can fill in missing points in a REM, such as Kriging, a regression technique used in geostatistics formulated by Matheron [

10] from his master’s thesis and paper published by Krige [

11]. Some Kriging methods are Ordinary Kriging, Simple Kriging, Universal Kriging, and Regression Kriging.

Conceptually, all these Kriging methods are the same, varying only in the parametric assumptions made. While Simple and Ordinary Kriging interpolate continuous spatial variable values with unbiased data and minimal variance, only Simple Kriging assumes that the mean of the local variables is similar to the population means, which are known. In Ordinary Kriging, the local variables and population mean are not necessarily equivalent [

12]. Meanwhile, in Universal Kriging, conceived by [

13] and called Regression Kriging by some authors, a coordinate function models the tendency.

Some works have investigated Kriging for interpolation tasks. For instance, Boshoff [

14] evaluates the Kriging techniques to obtain a REM of a simulated TV network and concludes that, in this case, the best results were obtained using the Ordinary Kriging technique. Boshoff [

14] also suggests using data from a functional network instead of a simulated one. Demonstrating that using Kriging for 802.11b/g/n standard wireless networks is possible, Han et al. [

8] published a paper applying the technique to a small network of three radios. The authors used smartphones to collect information in the database.

Hence, this work aims to develop a dedicated embedded system for monitoring wireless network quality in remote or restricted-access areas, using the Kriging technique for interpolation. We adopt Kriging because it provides the best linear unbiased prediction by explicitly modeling spatial autocorrelation through the variogram, minimizing prediction error variance compared to deterministic methods such as inverse distance weighting [

15,

16]. Unlike other alternatives, Kriging also quantifies prediction uncertainty, offering variances that help assess the reliability of interpolated values [

16]. Its flexibility in handling irregular data distributions and proven superior performance in geosciences, environmental monitoring, and mining applications make it particularly well-suited for our study [

17,

18].

The area of study is S11D’s iron ore processing plant. The outdoor wireless network at the S11D plant consists of 23 radios extending approximately two square kilometers, differing in size and complexity from previous work [

8]. Furthermore, the monitoring platform developed in this work is designed for use in industrial and extensive environments and can be attached to mobile machines.

Several open source tools exist for Wi-Fi monitoring, including MonFi [

19], IAX [

20], ORCA [

21], and the Open Source Capture and Analysis Tool [

22]. While these solutions demonstrate strong research contributions—ranging from high-rate programmable monitoring (MonFi), fine-grained CSI extraction (IAX), and software-defined control (ORCA) to frame-level security analysis and indoor occupancy estimation—they remain limited in scope for harsh industrial applications. In contrast, our system is designed for field-ready, outdoor, and industrial environments, combining performance metrics (RSSI, latency, packet loss, and throughput) with GPS-based geolocation and Kriging-based interpolation to generate actionable REMs. Moreover, unlike many tools focused on research or indoor applications, our platform prioritizes autonomy, safety, and cost-effective scalability, validated against a commercial benchmark, the Ekahau Site Survey.

Table 1 summarizes other open source tools in comparison to our work.

2. Design

The monitoring system comprises the following two modules: the “location” module, which aims to capture geographic coordinates, and the “performance” module, responsible for recording the network signal and performance data. The quality status of the wireless network monitored by the platform consists of measuring the following parameters:

Channeling is the frequency of data transmission and reception by the wireless network radios and clients. In Brazil, the allowed frequencies for 802.11b/g/n range from 2400 MHz to 2483.5 MHz [

23], which comprise channels 1 to 13.

RSSI describes the total received signal strength in dBm. Values typically range from −100 dBm for a weak signal to -60 dBm for strong signals [

24].

Latency (RTT—Round-Trip Time) is the time elapsed for a signal’s transit in a closed circuit. It can range from microseconds for a short radio system to many seconds for a multi-link circuit with one or more satellite links involved, including node delays and transit time on the transmission medium [

25].

Packet loss occurs when one or more data packets traveling through a computer network do not reach their destination. It measures the percentage of packets lost over the sent ones [

25].

Bandwidth is the maximum data transfer rate over a given path [

26], usually measured in Kbps or Mbps.

The location module’s central component is a GPS antenna model GY-NEO6MV2, which operates using the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84) geodetic reference system. We decided to use an antenna without differential GPS support because no base station is available for this purpose in the S11D complex. The module will accept the GPS antenna error of 2.5 m, according to [

27].

The performance module’s central component is a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B board with a sensor attached as follows: a standard 802.11b/g/n wireless antenna with a USB connector, Multilaser model RE034. This module also communicates with other computers and servers to deliver the measurements.

Figure 1 illustrates the communication between the sensors and the modules.

The decision to use an external Wi-Fi module instead of the Raspberry Pi’s integrated Wi-Fi or a smartphone’s Wi-Fi was based on several technical and practical considerations. Firstly, for this type of operation, it is crucial to have a Wi-Fi interface capable of entering promiscuous mode, which the internal interface of the Raspberry Pi does not support. This mode is essential for accurately reading signal strength in dBm. After testing several interfaces, we found one that met this requirement—a common necessity among Wi-Fi professionals.

External antennas offer superior signal capture and transmission over long distances and in rugged terrain, where signals can be easily obstructed. Additionally, using an external module offers flexibility in configuration, allowing for the selection of different types of antennas (such as directional or omnidirectional) tailored to the specific needs of the environment. This flexibility is not possible with the integrated Wi-Fi of the Raspberry Pi or a smartphone, which have fixed, generally lower-gain antennas.

Moreover, the Raspberry Pi is significantly more cost-effective than smartphones, offering a lower initial cost and greater operational flexibility. Smartphones are not only more expensive but also unsuitable for high-risk areas where signal level readings are needed. The Raspberry Pi setup eliminates the risk of accidents involving personnel using smartphones in hazardous environments.

Finally, external Wi-Fi modules are often designed for harsher conditions, providing greater resistance to interference and adverse weather conditions, which is crucial in mining operations. This robustness and durability ensure the network’s quality and reliability in such demanding environments.

Table 2 presents the parameters the platform measures, indicating which module and sensor perform each.

The software developed in Python (version 3.11.2) for the modules has four states of operation as follows: initial, search, collection, and final. All experiments were executed on a Raspberry Pi 3 running Raspbian (Buster) with Linux kernel version 5.10.x. The main Python packages and their versions utilized in this study are shown in

Table 3.

The Raspberry Pi serves as the central unit, coordinating the GPS receiver and Wi-Fi antenna via USB interfaces and Linux drivers. The system operates in unattended mode, automatically collecting data during machine operation without interfering with normal industrial processes.

The monitoring scripts automate data collection, geo-reference each measurement with GPS coordinates, and store results for interpolation. Given this modular architecture, the system can be extended with a mobile or web application to visualize radio environment maps in real time or to trigger alerts when thresholds are exceeded, supporting proactive network management.

The platform reads the coordinates’ file of the points of interest in the initial state. The system initializes the localization module, and the Raspberry Pi’s internal wireless network interface turns off. The program does not return to this state after its execution.

In the search state, the location module monitors the coordinates read by the GPS until it finds an interesting point within ten meters. We set this distance value because the GPS’s maximum error is 2.5 m, according to the manufacturer’s datasheet [

27]. Once found, the platform initiates the data collection state. The number of times the search state is visited equals the number of points of interest.

During the collection state, the location module collects GPS coordinates and timestamps, while the performance module collects SSID, RSSI, channelization, latency, packet loss, and bandwidth. After the collection finishes, the platform stores the data in text files in the performance module itself.

The final state starts after searching and collecting all points of interest. In this state, the performance module finishes running the program.

Bill of Materials Summary

This section covers the materials required to build the proposed system.

Table 4 lists the quantities, costs, purchase links, and material types.

5. Validation

5.1. Prototype Validation

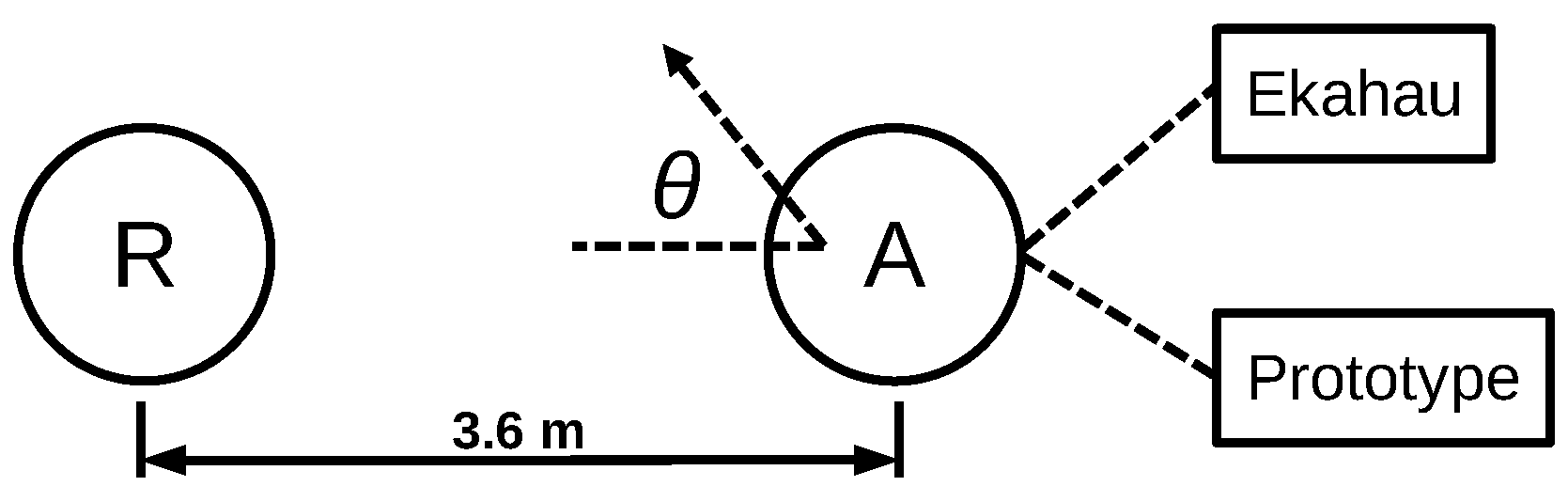

For the prototype’s validation, we set up a laboratory test scenario as shown in

Figure 3. We also installed a radio

R, model JR2-24 from the manufacturer Rajant, radiating a standard 802.11b/g/n wireless network, and a receiving antenna

A, model RE034 from the manufacturer Multilaser, at a fixed distance of 3.6 m from the

R.

We installed the prototype and the Ekahau Site Survey side by side using the same antenna (

A). By varying the transmission power of

R and the angle

of rotation of

A, the signal level (RSSI) received by the equipment and the Ekahau were measured alternately according to

Table 5. In this test, each device collected 240 examples, totaling 480 samples. It is worth mentioning that no one was connected to this wireless network during the test.

5.2. In Loco Field Test

The field tests to compare the prototype with the Ekahau Site Survey, Vale’s official wireless network monitoring tool, were performed during a visit to the processing plant of the S11D complex. The test consisted of traveling between 27 points of interest distributed around the stockyard (see

Figure 4) and stopping the vehicle when reaching each. Thus, the prototype could collect all the parameters of these points. In parallel, with the car still stopped, the same parameters were gathered with the Ekahau Site Survey.

The product stockyard of the S11D power plant has the coverage of a standard 802.11b/g/n wireless network, approximately 0.35 km

2 (see

Figure 5), which consists of the following:

Twelve Cisco model AIR-CAP1552E-N-K9 radios with three Cisco model AIR-ANT2568VG-N antennas each at fixed points.

Sixteen Cisco model AIR-LAP1261N-A-K9 radios, each with a Cisco model AIR-ANT2440NV-R antenna, installed in yard machines such as the stacker–reclaimer and yard stacker.

Two wireless Cisco model AIR-CT5508-50-K9 network controllers were installed at the data center.

In this context, understanding the application’s requirements is necessary to evaluate the quality of the monitoring network. The application 800xA from the manufacturer ABB is used in the S11D plant, which allows the control of the PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) of the stacker–reclaimer and yard stacker machines. The requirements for this application depend on the number of PLCs installed in each machine and the time it takes to send each instruction from the server to the PLC. Vale provided the minimum requirements for the correct operation of this application in this yard, which we describe in

Table 6.

We classified the monitored points of interest into the following categories:

Not observed: When there was no measurement of the point.

Does not meet (Unsatisfactory): When two or more parameters are outside the minimum requirements. In this situation, the network is unable to guarantee the safe and stable execution of control commands, and corrective action, such as adding new access points or redesigning the coverage area, is required.

Complies with restrictions (Satisfactory with restrictions): When exactly one parameter is outside the minimum requirements. In this case, the application may still function, but with degraded performance. This classification indicates the need for optimization measures such as antenna realignment, transmit power adjustment, or selective reinforcement of coverage.

Complies: When all parameters are within the minimum requirements.

For this comparison test, in addition to the prototype, we used an extra Raspberry Pi installed in the S11D technology server room to perform as an IPERF server. We also used a notebook with Ekahau Site Survey software licensed and installed, and an external antenna was attached to the vehicle’s roof.

The system is unable to recover network parameters in the absence of a radio signal. Under conditions of high packet loss—specifically, at 100% loss—iperf cannot report throughput or jitter. RTT is measured with ping, which also fails to produce RTT values when no ICMP replies are received (i.e., 100% loss). Nonetheless, it remains possible to obtain the RSSI, as this parameter does not depend on the successful transmission of data packets.

5.3. Use in the Stacker Machine

The final prototype test aims to collect RSSI parameters at specific points within the product storage yard to generate the REM using Kriging interpolation. A stacker machine with recurrent wireless network connection issues was deliberately chosen to ensure that the REM would provide results directly applicable to the operation. As the stacker moves along a straight rail, monitoring points are set at 50 m intervals along the rail to ensure accurate tracking of its movements, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

The testing procedure for the prototype mirrors the methodology employed in the previous sections. As the stacker machine passes through designated points of interest, the program collects relevant parameters, which are subsequently stored in output text files. These files are later analyzed, and the RSSI data collected at each point serve as input for generating the REM using the Ordinary Kriging method.

5.4. Prototype Validation Results

Figure 7 shows the result of the sample collection in mW. It is possible to see the step shape every 15 instances due to the change in radio transmission power. Every 60 samples, the rotation of the antenna also changes the received signal level patterns according to its radiation diagram.

We plotted an error bar graph for the 16 sample sets in

Table 5 to effectively compare the Ekahau Site Survey and the prototype. Each error bar has its center point at the average RSSI of each sample set and has upper and lower limits that represent a standard deviation from the average. This graph, illustrated in

Figure 8, allows us to see how close the measurements are between the Ekahau Site Survey and the prototype.

One point to note is that the error bars for all 16 sample sets intersect, indicating that the sample measurements between the Ekahau Site Survey and the developed prototype are equivalent. It is further emphasized that the error bars in sets 1, 5, 9, and 13 are larger due to the logarithmic nature of RSSI, as this parameter was obtained in dBm by both Ekahau and the prototype during testing and was subsequently converted to mW in the representation shown in

Figure 8. The maximum standard deviation observed was

mW for sample 5.

5.5. In Loco Test Results

Although we mapped 27 points of interest for the collection of network parameters, we could only visit some of them. A deviation was necessary at points 12, 15, 16, and 17 due to road closures for civil construction. This situation highlights the difficulty of accessing points of interest for outdoor wireless network monitoring in the mining industry.

Table 7 reveals the nodes’ classifications and identifies the results of the Ekahau Site Survey and the developed platform.

With this mapping, it is possible to observe that the Ekahau Site Survey, unlike the developed platform, separates the points into only two classifications as follows: “Satisfy” and “Unsatisfactory”. Therefore, we assume that the nodes that the developed platform classifies as "Satisfy with restrictions" will fall into one of these two classifications (case of points 4, 6, 10, 11, 13, 14, 19, 20, 23, 24, 26, and 27). The “Unobserved” points are classified by the Ekahau Site Survey employing interpolation (case of points 12, 15, 16, and 17).

All the other remaining points have identical scores in the comparison, except point 21. The analyses of the RSSI comparisons developed below are necessary for a more assertive evaluation of this last point.

To compare the prototype with the mapping results from the Ekahau Site Survey, the RSSI for the region around the mapped points of interest must be interpolated. We interpolated these using the Variogram and Kriging algorithms available in the Python library Scikit-GStat [

28]. We used the RSSI measurements collected from the 23 points as input in this task. Interpolation via Ordinary Kriging was calculated for points every 10 m.

Figure 9 shows the results of the comparison.

In both maps, we highlight seven similar regions. Region 1 has a higher RSSI due to the radio installed at the beginning of the courtyard. Region 2 represents a large area with a lower signal level, followed by Region 3, which increases RSSI. Region 4 presents the highest RSSI in both maps. Regions 5 and 6 are under one radio each on the other side of the yard, and Region 7 is at a good RSSI level because two radios cover it.

We present a more detailed analysis by region as follows:

Region 1 has one of the highest RSSI levels. It contains points 1 and 2 in

Figure 4. Both meet the application requirements. Therefore, it is a region in which the wireless network meets the requirements for iron ore processing.

Region 2 highlights a large area with a lower RSSI level. It contains points 3 to 6 in

Figure 4. None of these points fully meets the application requirements. Therefore, it is one of the regions that should improve the wireless network quality.

Region 3 has the highest RSSI level. It contains points 7 and 8 in

Figure 4. Both meet the application requirements. Therefore, it is a region in which the wireless network meets the requirements for iron ore processing.

Region 4 shows the region with the highest RSSI in

Figure 9a,b. It contains points 9 and 10 from

Figure 4. One point fully meets the application requirements, while the other meets them only partially. Although it has higher wireless network quality than region 2, it is one of the regions for which wireless network quality should be improved.

Region 5 is under a wireless network radio. It contains points 18 to 20 in

Figure 4. While point 18 does not meet the application requirements, points 19 and 20 partially do. Therefore, despite a higher RSSI level, this region must undergo wireless network enhancements to meet the application requirements fully.

Region 6 is under a wireless network radio. It contains points 22 and 23 in

Figure 4. While point 22 does not meet the application requirements, point 23 partially does. Therefore, despite a higher RSSI level, this region must undergo wireless network enhancements to meet the application requirements fully.

Region 7 has one of the highest RSSI levels in

Figure 4. It contains points 24 to 27. In this region, all points meet the application requirements to some extent. Although it has higher wireless network quality than regions 5 and 6, it is one of the regions that should continue to improve its wireless network quality.

Finally, comparing

Figure 4 and

Figure 9 shows that point 21 is located between regions 5 and 6. The previous analysis concluded that both regions should undergo wireless network improvements. In addition, the following point (22) does not meet the application requirements (see

Table 7) even though it is located directly below a radio (see

Figure 5). It is reasonable to conclude that this radio is not operating correctly, and for these reasons, point 21 does not meet the application requirements.

5.6. Quantitative Comparison Between the Prototype and Ekahau Site Survey

To complement our qualitative analysis, we performed a quantitative comparison of the RSSI measurements across the seven identified regions.

Table 8 presents the mean RSSI values in mW and their respective standard deviations for both systems.

To quantify the similarity between the two measurement systems, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between the RSSI values in the linear mW scale, obtaining a value of . This moderate positive correlation indicates that despite some differences in absolute readings, both systems capture similar relative signal strength patterns across the monitored area. This finding supports our qualitative analysis, which suggests that network specialists would likely make similar decisions regarding network quality and improvement strategies when using either system.

Further analysis of the data shows that regions with the strongest signals (Regions 1, 4, and 7) and weakest signals (Region 2) were consistently identified by both systems, supporting our qualitative conclusion that network specialists would make similar decisions using either tool. The most significant discrepancies were observed in Regions 5 and 7, which can be attributed to differences in the prediction algorithms between systems. While our prototype uses documented Kriging interpolation, Ekahau employs proprietary algorithms that are not publicly disclosed. Since both systems were exposed to identical environmental conditions, these mathematical differences in signal processing are the most likely explanation for the observed variations.

It is worth noting that the prototype generally exhibited lower standard deviations in most regions, suggesting more consistent readings under the test conditions. This consistency, combined with the demonstrated correlation with Ekahau measurements, further validates the prototype’s utility for wireless network monitoring in mining environments.

5.7. Stacker Machine Usage Results

The prototype is secured to a handrail using nylon ties and connected to a power source on a nearby distribution board. Given that the prototype weighs approximately 300 g, a more robust installation was deemed unnecessary. Because of its compact design and seamless integration with mobile equipment, the platform can continuously operate in the yard. Its outputs can also feed higher-level applications such as dashboards or maintenance alert systems, thereby improving the decision-making process for network deployment and remediation.

When installing the platform on mining machinery, several safety and operational considerations must be taken into account. The device is lightweight, but it must be securely fixed to withstand vibrations. This prevents interference with machine operation. Electrical protection is ensured by a DC-DC regulator with a fuse. This setup prevents any connection to safety-critical circuits. The hardware must be housed in an enclosure due to harsh outdoor conditions. This enclosure shields against dust, rain, and mechanical shocks. Proper antenna positioning is essential. Good placement minimizes obstructions from metallic structures or ore piles that could degrade signal quality. The GPS accuracy margin is about 2.5 m. This margin must be addressed, especially in areas with multipath effects or partial blockages. Automation features, such as auto-start configuration and remote operation, are also crucial. They reduce the need for human intervention in hazardous areas, increasing both safety and efficiency.

Although 18 points of interest were mapped for network parameter collection, the forklift EP-2091KS-03 only visited points 7 through 13 during its operational route.

The REM could not be generated concurrently using the Ekahau Site Survey because the area where the stacker operates is inaccessible to a mapping vehicle. Additionally, conducting this mapping on foot with a laptop is not feasible, as the area is very dangerous and access is restricted. In this context, our work contributes by enabling the capture of network parameters in a location where Vale’s tools have previously been unable to do so.

It is also important to note that the Ekahau Site Survey (ESS) does not support automatic monitoring, requiring the local intervention of an operator to initiate and complete the mapping process. If the operator does not have a GPS receiver installed and configured on their notebook to work with the ESS, they must manually mark the reading positions on the map. The platform developed in this work replaces the entire process because it eliminates the need for any intervention during data collection, allowing the algorithm to be initiated remotely.

The analysis of

Figure 10 reveals a blue region in the courtyard’s center, indicating a low signal level. This area corresponds precisely to the location where the stacker was operating on the data collection date. The communication problems experienced by the stacker can be correlated with the interpolation results. These issues are likely due to signal obstruction caused by the piles of ore surrounding the machine.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we developed an outdoor wireless network monitoring platform. We tested the platform in the laboratory and in loco (area of the stockyard) to compare its diagnosis with the diagnosis generated by the commercial tool used by Vale. We verified that both have significant similarities in the generated map, which would allow the local network operation team to replace the Ekahau Site Survey with the platform developed in this work.

With the map generated by the developed platform and illustrated in

Figure 9a, some actions could be taken to decrease the production stoppage hours at the S11D complex due to wireless network problems. These actions would be the same as if we used the analysis in

Figure 9b as the basis and they are outlined as follows:

Identification of problem radios for corrective maintenance.

Changing wireless network settings on the radios or controller.

Increasing or decreasing the transmission power of the installed radios.

Installation of more radios in regions with insufficient RSSI levels.

Replacement of radio antennas with different gains or apertures.

Hardware or software upgrade for obsolete radios.

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the platform developed in this work does not depend on human intervention to collect the network quality status, which eliminates exposure to risk for Vale’s employees who currently perform this work with the Ekahau Site Survey. On the developed platform, human intervention is required only to start the software and for the final collection, which can be done remotely from a secure workstation.

The monitoring platform developed in this work can be replicated in the future for decentralized installation in several mobile mining and processing machines of the complex because it has simpler hardware than the Ekahau Site Survey, being this hardware composed of a Raspberry Pi, a GPS antenna, and a wireless network antenna, besides the electrical connection cables. On the other hand, the Ekahau Site Survey features a centralized architecture, executed through a single notebook with the licensed software installed.

It is also important to emphasize that the platform is not restricted only to mining and processing areas but can be applied in other industrial domains such as ports, railroads, and large-scale outdoor facilities, where wireless coverage is equally mission-critical and infrastructure presents similar constraints.

The implementation of the platform at multiple locations within an operating area would ensure the generation of more comprehensive REMs. These REMs could be automatically produced to facilitate near real-time monitoring of the wireless network’s health, enabling optimization and adjustments to maintain network integrity. Additionally, the system’s remote operation feature allows for dynamic changes to monitoring coordinates, ensuring expanded and adaptive coverage.

Finally, future enhancements will also focus on low-power operation for battery-constrained deployments, tighter integration with IoT and sensing modules, and improved modularity to allow rapid adaptation to diverse industrial scenarios. These developments will broaden the platform’s applicability and long-term impact.