Blockchain Technology Application Domains along the E-Commerce Value Chain—A Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To examine the applications of Blockchain Technology along the e-commerce value chain according to news articles and to categorise them into application domains;

- To discuss why Blockchain Technology is utilised in these applications domains.

2. Background

2.1. Blockchain Technology, Smart Contracts, and Tokens

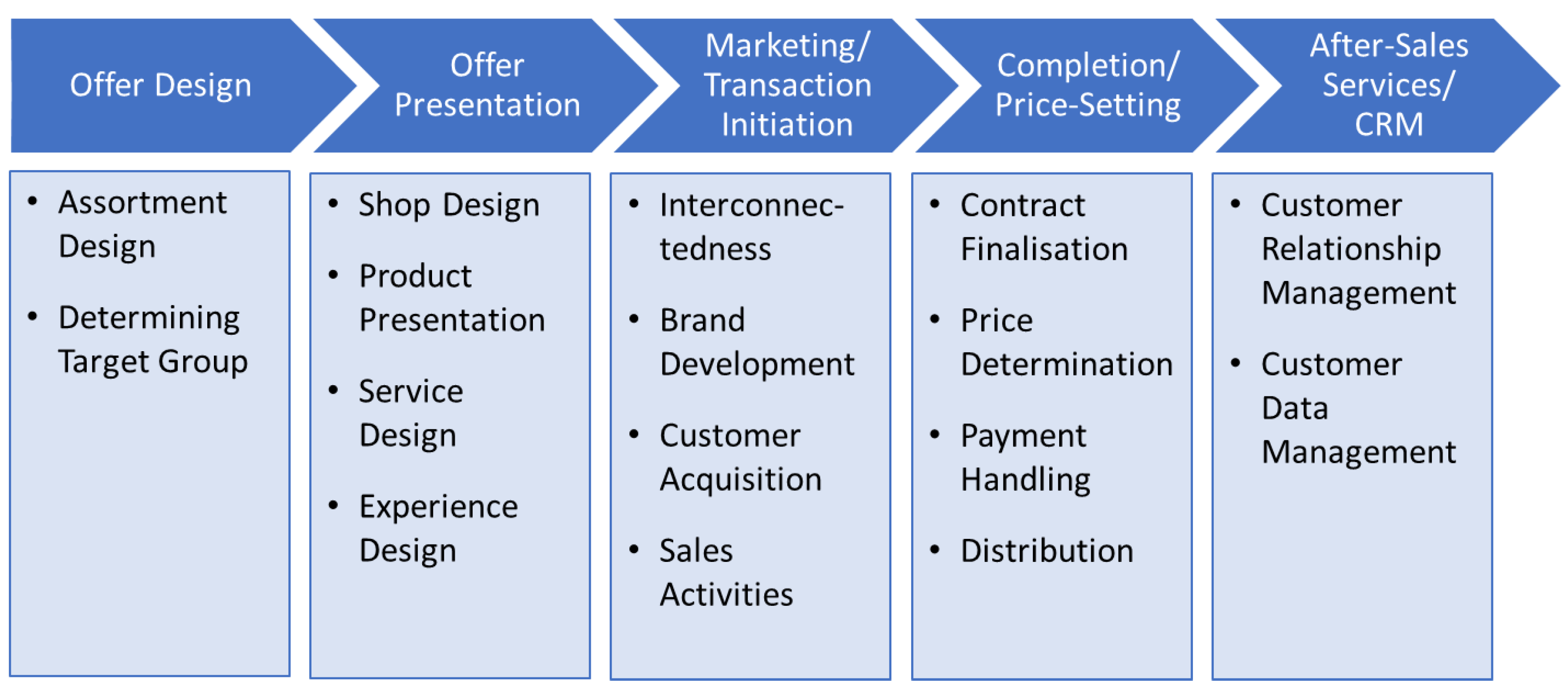

2.2. State-of-the-Art on Blockchain Technology Use Cases along the E-Commerce Value Chain

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. News Article Selection

3.2. Qualitative Content Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Offer Design

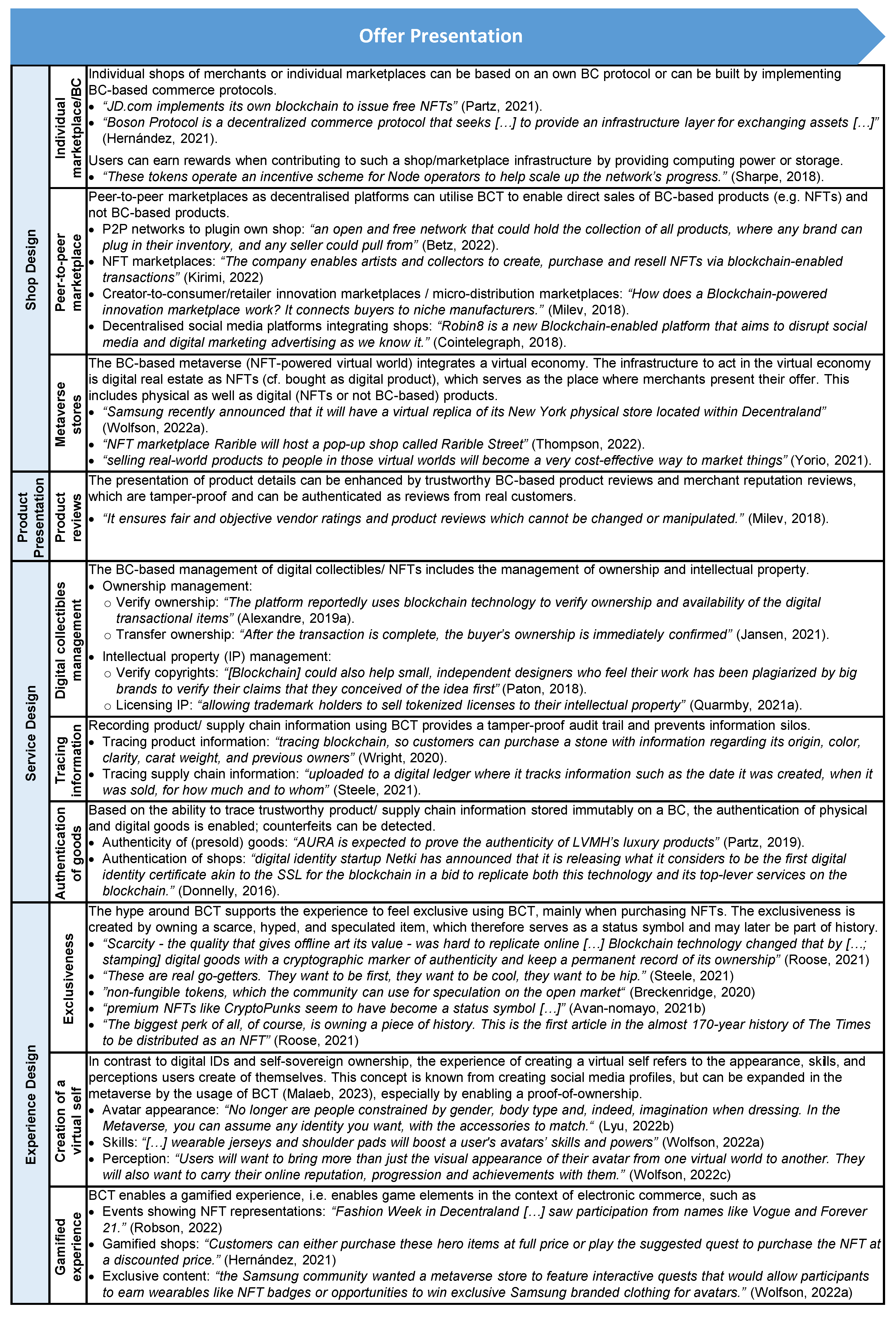

4.2. Offer Presentation

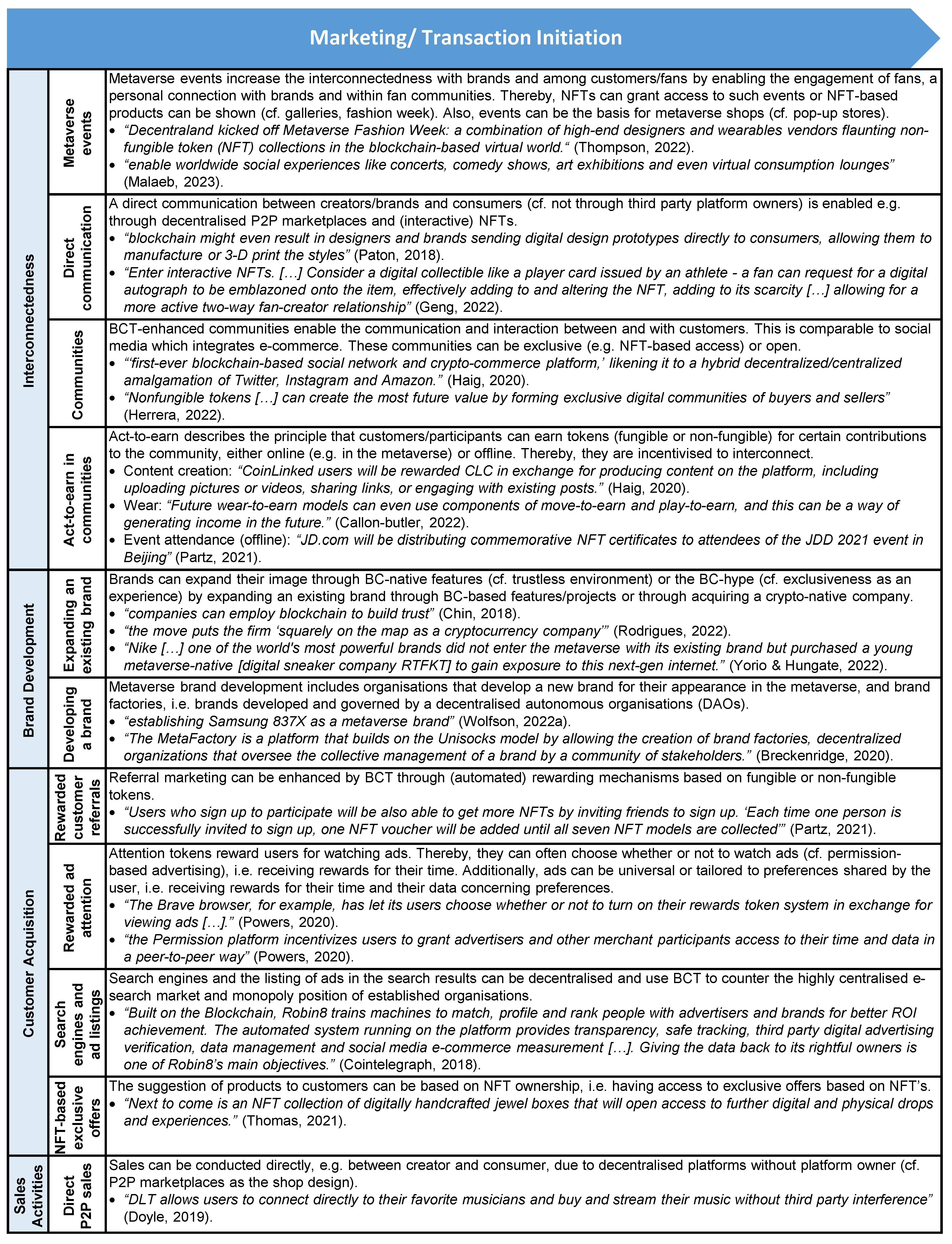

4.3. Marketing/Transaction Initiation

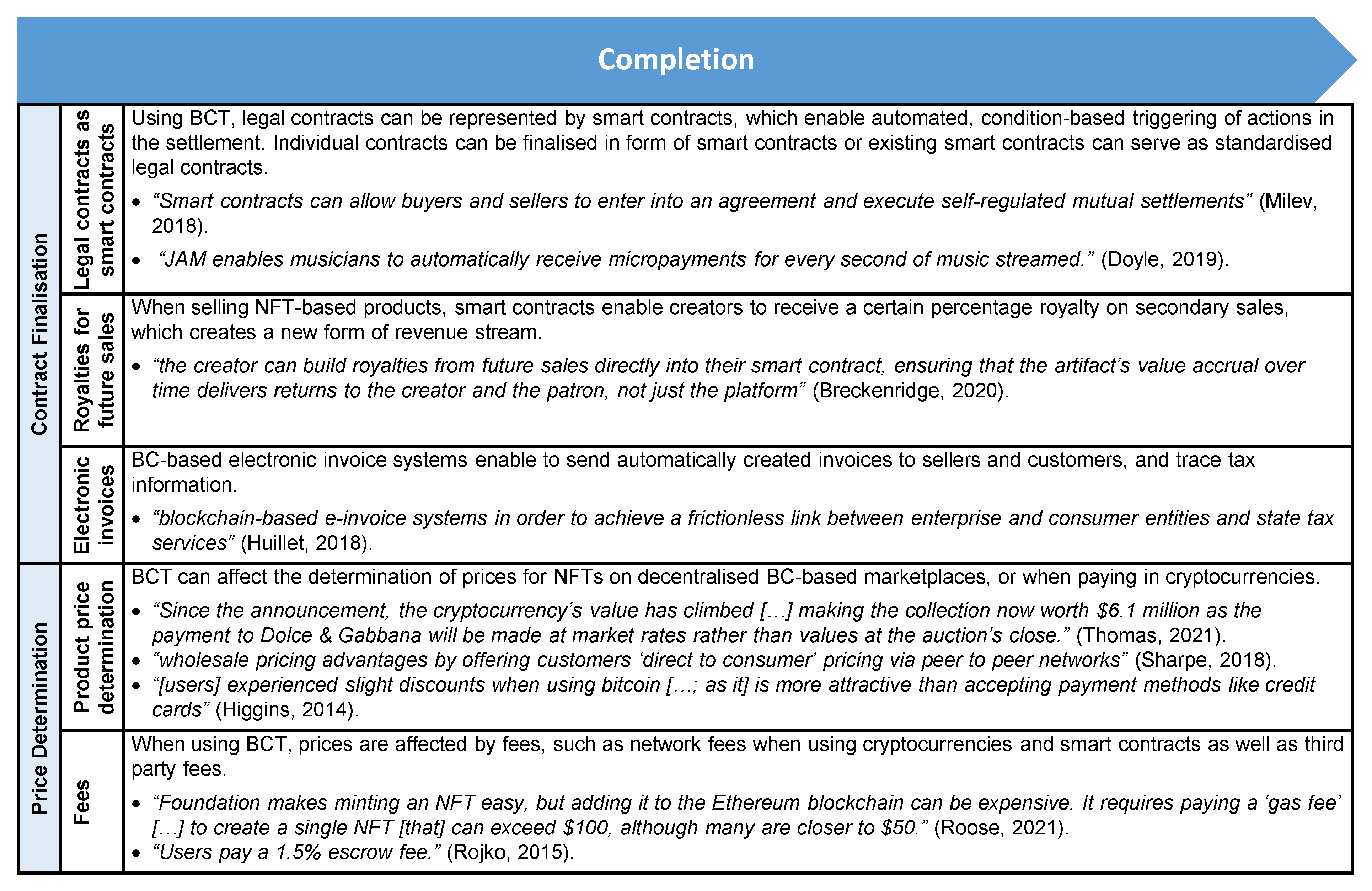

4.4. Completion

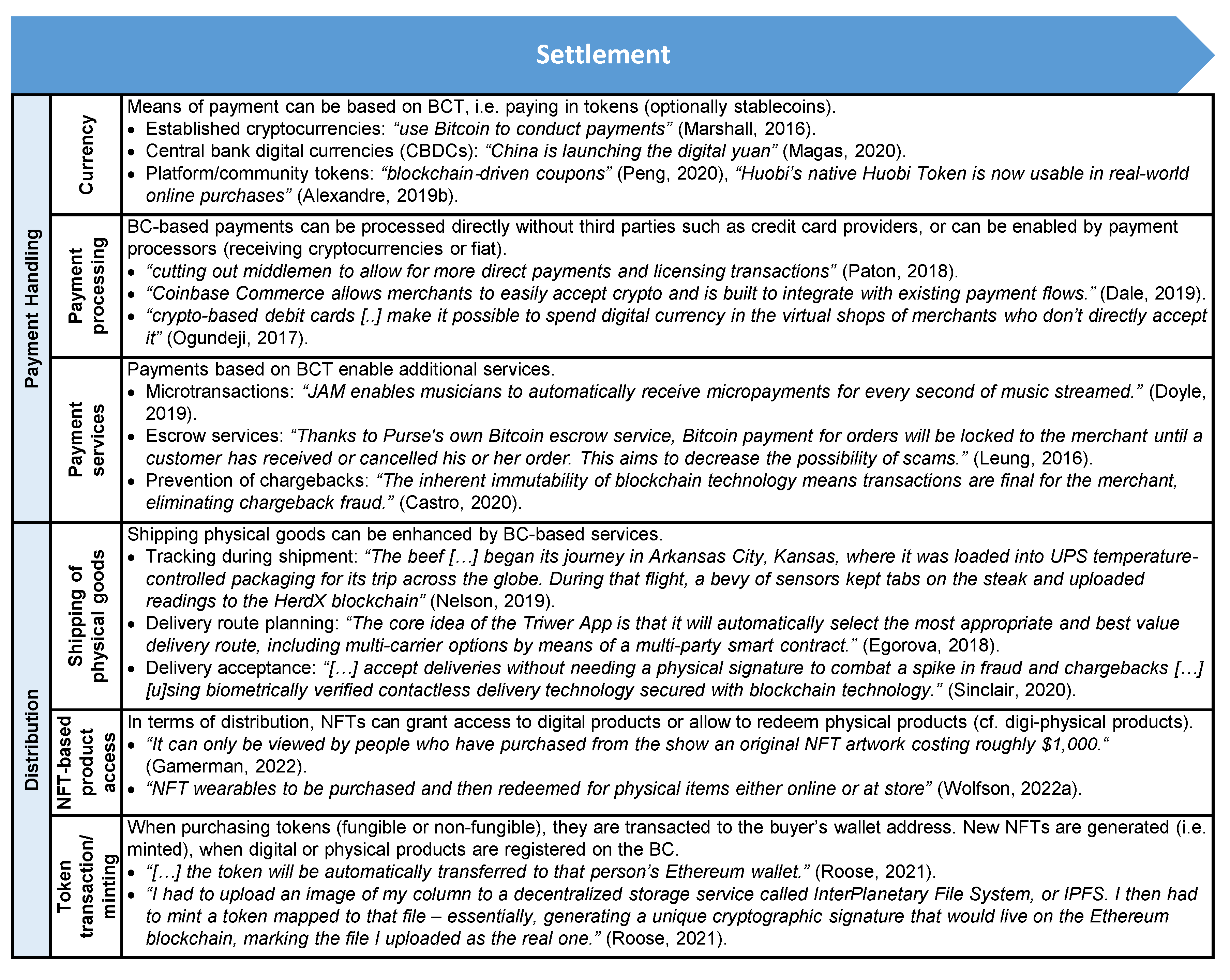

4.5. Settlement

4.6. After-Sale Services

5. Discussion

- The new target group of Blockchain/crypto enthusiasts is an opportunity to expand a business as they are early adopters willing to spend a lot of money on innovative products.

- The experience design is an important aspect besides purely convincing customers of the benefits of BCT.

- The interconnectedness through communities is of particular importance in BC-based e-commerce.

- Instead of just expanding a business, many organisations benefit from developing a brand specialised in BCT products and services.

- The completion and settlement are well understood in BC-based e-commerce and do not provide a competitive advantage or unique selling point for Blockchain enthusiasts.

- Even though customers aim for data ownership and self-sovereign identity, CRM is still an important aspect of after-sale services and can be enhanced by BCT.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gassmann, O.; Frankenberger, K.; Csik, M. The Business Model Navigator: 55 Models that Will Revolutionise Your Business; Pearson: Harlow, UK; London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Boston, MA, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D.; Tapscott, A. Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies Is Changing the World; Portfolio/Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, J. When is Blockchain Technology Valuable?—A State-of-the-Art Analysis. In Proceedings of the UK Academy for Information Systems 2021 (UKAIS2021), Online Conference, 23–24 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Li, Z.; Qiao, G. Trust Building in Cross-border E-Commerce: A Blockchain-Based Approach for B2B Platform Interoperability. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on Knowledge and Systems Sciences, (KSS 2023), Guangzhou, China, 2–3 December 2023; pp. 246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Guntara, R.G.; Nurfirmansyah, M.N.; Ferdiansyah. Blockchain Implementation in E-Commerce to Improve The Security Online Transactions. JSRET J. Sci. Res. Educ. Technol. 2023, 2, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Be, K.; Shi, Q. Research on the Information Tracing Model for Cross-border E-commerce Products based on Blockchain. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 235, 03018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yeon, C. Blockchain-Based Traceability for Anti-Counterfeit in Cross-Border E-Commerce Transactions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Sillaber, C. The impact of blockchain on e-commerce: A framework for salient research topics. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 48, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, Y. Blockchain-Enabled Cross-Border E-Commerce Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Madanchian, M. Blockchain-Based E-Commerce: A Review on Applications and Challenges. Electronics 2023, 12, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qusa, H.; Tarazi, J.; Akre, V. Secure E-Auction System Using Blockchain: UAE Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2020 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2–9 April 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan, Ö.; Karacan, H. A Blockchain-Based E-Commerce Reputation System Built with Verifiable Credentials. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 47080–47097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.; Lim, E.; Hua, X.; Zheng, S.; Tan, C.-W. Business on Chain: A Comparative Case Study of Five Blockchain-Inspired Business Models. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 20, 1310–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, J.; Schoop, M. Blockchain technology in e-business value chains. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Strategy and the Internet. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, L.; Thomas, I.; Martin, A. Review: Ecological awareness, anxiety, and actions among youth and their parents—A qualitative study of newspaper narratives. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busam, B.; Solomon-Moore, E. Public Understanding of Childhood Obesity: Qualitative Analysis of News Articles and Comments on Facebook. Health Commun. 2023, 38, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Choudhury, S.; Basu, A.; Mahintamani, T.; Sharma, K.; Pillai, R.R.; Basu, D.; Mattoo, S.K. Extended lockdown and India’s alcohol policy: A qualitative analysis of newspaper articles. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 85, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, F.; Hawlitschek, F.; Notheisen, B. Blockchain as a Platform. In Business Transformation through Blockchain; Treiblmaier, H., Beck, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Seebacher, S.; Schüritz, R. Blockchain Technology as an Enabler of Service Systems: A Structured Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Exploring Services Science (IESS), Rome, Italy, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Weber, I.; Zhu, L.; Staples, M.; Bosch, J.; Bass, L.; Pautasso, C.; Rimba, P. A Taxonomy of Blockchain-based Systems for Architecture Design. In Proceedings of the 1st IEEE International Conference on Software Architecture, Gothenburg, Sweden, 5–7 April 2017; pp. 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, R.; Liu, L. Security and Privacy on Blockchain. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, K.; Xiao, L.; Cai, J.; Liang, W.; Castiglione, A. A Systematic Review of Consensus Mechanisms in Blockchain. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, B.; Musilek, P. A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43620–43652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Srivastava, G.; Karimipour, H. Secure Intelligent Fuzzy Blockchain Framework: Effective Threat Detection in IoT Networks. Comput. Ind. 2023, 144, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Hammoudeh, M.; Karimipour, H.; Srivastava, G. Block Hunter: Federated Learning for Cyber Threat Hunting in Blockchain-Based IIoT Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2022, 18, 8356–8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, F. Pervasive Decentralisation of Digital Infrastructures: A Framework for Blockchain enabled System and Use Case Analysis. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Qin, R.; Wang, F.-Y. An Overview of Smart Contract: Architecture, Applications, and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiderowski, J.; Pedersen, A.B.; Beck, R. Crypto Tokens and Token Systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freni, P.; Ferro, E.; Moncada, R. Tokenomics and blockchain tokens: A design-oriented morphological framework. Blockchain: Res. Appl. 2022, 3, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Zavolokina, L.; Bauer, I.; Schwabe, G. To Token or not to Token: Tools for Understanding Blockchain Tokens. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ethereum.org. Token Standards. Available online: https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/standards/tokens/ (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Borri, N.; Liu, Y.; Tsyvinski, A. The Economics of Non-Fungible Tokens. SSRN J. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Roubaud, D. Non-Fungible Token: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, E.; Wat, F. A literature review and classification of electronic commerce research. Inf. Manag. 2002, 39, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, E.; King, D.; Lee, J.K.; Liang, T.-P.; Turban, D.C. Electronic Commerce, 8th ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beinke, J.H.; Nguyen, D.; Teuteberg, F. Towards a Business Model Taxonomy of Startups in the Finance Sector using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kazan, E.; Tan, C.-W.; Lim, E.T.K. Value Creation in Cryptocurrency Networks: Towards A Taxonomy of Digital Business Models for Bitcoin Companies. In Proceedings of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Singapore, 5–9 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Viriyasitavat, W.; Xu, L.D.; Bi, Z.; Sapsomboon, A. Blockchain-based business process management (BPM) framework for service composition in industry 4.0. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, H.; Haq, I.U. Blockchain and IoT Based Disruption in Logistics. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Communication, Computing and Digital Systems (C-CODE), Islamabad, Pakistan, 6–7 March 2019; pp. 276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.E.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lu, M.-F. Supply chain re-engineering using blockchain technology: A case of smart contract based tracking process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W. Digital Business Models: Concepts, Models, and the Alphabet Case Study; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W. Electronic Business, 6th ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Wells, T.M.; Moody, G.; Humpherys, S.; Kettles, D. Online Payment Gateways Used to Facilitate E-Commerce Transactions and Improve Risk Management. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2006, 17, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antovski, L.; Gusev, M. M-payments. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Information Technology Interfaces (ITI), Cavtat, Croatia, 16–19 June 2003; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, M.; Weber, G. Social Media Marketing Strategies Based on CRM Value Chain Model. Int. J. Innov. Mark. Elem. 2022, 2, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahay, D. Advancing research in digital and social media marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, W.; Zainab, H.e.; Imran, J.; Bawany, N.Z. NFTs: Applications and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Muscat, Oman, 21–23 December 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, H.; Ko, N. Blockchain based Data Marketplace System. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on ICT Convergence (ICTC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 1255–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrenz, S.; Sharma, P.; Rausch, A. Blockchain Technology as an Approach for Data Marketplaces. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Blockchain Technology (ICBCT), Honolulu, HI, USA, 15–18 March 2019; pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sober, M.; Scaffino, G.; Schulte, S.; Kanhere, S.S. A blockchain-based IoT data marketplace. Cluster Comput. 2023, 26, 3523–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, J.; Karkazis, P.A.; Papadopoulos, P.; Leligou, H.C. Decentralized Blockchain-Based IoT Data Marketplaces. JSAN 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, R.-V.; Ilie, D.; Robert, R.; Kebande, V.; Tutschku, K. Towards efficient privacy and trust in decentralized blockchain-based peer-to-peer renewable energy marketplace. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 35, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, M.T.; Cuffe, P. Blockchain Electricity Trading Under Demurrage. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 2323–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, V.; George, L.; Badis, H.; Desta, A.A. Blockchain Based Decentralized Framework for Energy Demand Response Marketplace. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium (NOMS 2020), Budapest, Hungary, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ahokangas, P.; Yrjölä, S.; Koivumäki, T. The fifth archetype of electricity market: The blockchain marketplace. Wireless Netw. 2021, 27, 4247–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S. ArtChain: Blockchain-Enabled Platform for Art Marketplace. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Blockchain, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 July 2019; pp. 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Grintsvayg, A.; Kauffman, J.; Fleming, C. LBRY: A Blockchain-Based Decentralized Digital Content Marketplace. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures, Oxford, UK, 3–6 August 2020; pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kadir, K.A.; Wahab, N.H.A.; Soh, N.Z.R.; Teoh, X.G.; Luk, S.; Zin, A.W.M. OWNTRAD: A Blockchain-Based Decentralized Application for Vintage E-commerce Marketplaces. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Wireless Technology & Applications (ISWTA 2023), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 15–16 August 2023; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, M.; Yang, C.-N.; Fu, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, Q.J. Blockchain-based decentralized reputation system in E-commerce environment. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 124, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lal, C.; Conti, M.; Alazab, M. Anonymous and Verifiable Reputation System for E-Commerce Platforms Based on Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 4434–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.; Wörner, D.; Ilic, A. Collaborative Filtering on the Blockchain: A Secure Recommender System for e-Commerce. In Proceedings of the 22nd Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), San Diego, CA, USA, 11–14 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xue, R.; Zhang, R.; Su, Q.; Gao, S. RTChain: A Reputation System with Transaction and Consensus Incentives for E-commerce Blockchain. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2021, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Pereira, R.H.; Coelho, M.A.G.M. User Reputation on E-Commerce: Blockchain-Based Approaches. JCP J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Laskowski, M. Towards an Ontology-Driven Blockchain Design for Supply Chain Provenance. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2018, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Xiao, X. Research on Decision Support System of E-Commerce Agricultural Products Based on Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on E-Commerce and Internet Technology (ECIT), Zhangjiajie, China, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Fan, Z.-P.; Wu, X.-Y. The Choice Strategy of Authentication Technology for Luxury E-Commerce Platforms in the Blockchain Era. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Dash, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S. How is Blockchain used in marketing: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2021, 1, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallone, V.; Wetzels, M.; Klaas, M. Applications of Blockchain Technology in marketing—A systematic review of marketing technology companies. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Saraniemi, S. Trust in blockchain-enabled exchanges: Future directions in blockchain marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 914–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, R.; Schreier, M.; Schweidel, D.A.; Sorescu, A. Blockchain meets marketing: Opportunities, threats, and avenues for future research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertemel, A.V. Implications of Blockchain Technology on Marketing. J. Int. Trade Logist. Law 2018, 4, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ante, L. Smart contracts on the blockchain—A bibliometric analysis and review. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 57, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Smart Contracts in Blockchain Technology: A Critical Review. Information 2023, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenfein, J.; Leiter, A. Legal Engineering on the Blockchain: ‘Smart Contracts’ as Legal Conduct. Law Crit. 2018, 29, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governatori, G.; Idelberger, F.; Milosevic, Z.; Riveret, R.; Sartor, G.; Xu, X. On legal contracts, imperative and declarative smart contracts, and blockchain systems. Artif. Intell. Law 2018, 26, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karle, R.; Witt, J. An Empirical Approach on Exploring NFT Launch Strategies. In Proceedings of the Blockchain Autumn School, Mittweida, Germany, 11–15 September 2023; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eikmanns, B.C.; Sandner, P.G. Bitcoin: The Next Revolution in International Payment Processing? An Empirical Analysis of Potential Use Cases. SSRN J. 2015, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.W.; Panayi, E.; Chapelle, A. Trends in Crypto-Currencies and Blockchain Technologies: A Monetary Theory and Regulation Perspective. SSRN J. 2015, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-I.; Kim, S.-H. E-commerce payment model using blockchain. J. Ambient Intell. Human Comput. 2022, 13, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Sakamoto, M. Blockchain-LI: A Study on Implementing Activity-Based Micro-Pricing using Cryptocurrency Technologies. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multi Media, Singapore, 28–30 November 2016; pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bel Hadj Youssef, S.; Boudriga, N. A Robust and Efficient Micropayment Infrastructure Using Blockchain for e-Commerce. In Intelligent Computing: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Arai, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 825–839. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, J.; Richter, S. Ein problemzentrierter Blick auf Blockchain Anwendungsfälle. In Proceedings of the Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik (MKWI), Lüneburg, Germany, 6–9 March 2018; pp. 1247–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Javangula, V.; Hu, Q.; Wang, S.; Cheng, X. NormaChain: A Blockchain-Based Normalized Autonomous Transaction Settlement System for IoT-Based E-Commerce. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4680–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z. A blockchain-based framework of cross-border e-commerce supply chain. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachana Harish, A.; Liu, X.L.; Zhong, R.Y.; Huang, G.Q. Log-flock: A blockchain-enabled platform for digital asset valuation and risk assessment in E-commerce logistics financing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Blockchain Technology and Artificial Intelligence Together: A Critical Review on Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M.; Senthilkumar, N.; Girimurugan, B.; P, L.A.; Hasan, K.s.; Sanjay. Customer Relationship Management in the Digital Age by Implementing Blockchain for Enhanced Data Security and Customer Trust. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 March 2024; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ismanto, L.; Ar, H.S.; Fajar, A.N.; Sfenrianto; Bachtiar, S. Blockchain as E-Commerce Platform in Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1179, 012114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L. A Privacy-Preserving E-Commerce System Based on the Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Workshop on Blockchain Oriented Software Engineering (IWBOSE), Hangzhou, China, 24 February 2019; pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, J. Framework of Blockchain-Supported E-Commerce Platform for Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, C. A Novel Decentralized E-Commerce Transaction System Based on Blockchain. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorman, S.M.; Allaymounq, M.; Hamid, O. Developing the E-Commerce Model a Consumer to Consumer Using Blockchain Network Technique. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Technol. 2019, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, E.; Aydemir, M.F. Blockchain-Based E-Commerce: An Evaluation. Int. J. Soc. Inq. 2022, 15, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, D.; Chamberlain, K. Analysing News Media. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 380–393. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, T. Top 15 Best Crypto News Websites in 2024. Prestmit [Online], 31 August 2023. Available online: https://prestmit.com/blog/top-15-best-crypto-news-websites/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Bhattacharya, J. 10 Best Crypto News Websites for 2024. Ninjapromo [Online], 16 January 2024. Available online: https://ninjapromo.io/best-crypto-news-websites (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Luis. The 14 Best Crypto News Outlets in 2023 [Online], 25 January 2023. Available online: https://cointracking.info/blog/the-best-crypto-news-outlets/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Legge, M. 11 Best Crypto News Websites in 2024. Koinly [Online], 22 January 2024. Available online: https://koinly.io/de/blog/best-crypto-news-websites/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 13th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann, T.; Stieglitz, S.; Cvetkovic, A. Prevalent Business Models for the Apple App Store. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI), Osnabrueck, Germany, 4–6 March 2015; pp. 1206–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Valtanen, K.; Backman, J.; Yrjola, S. Blockchain-Powered Value Creation in the 5G and Smart Grid Use Cases. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 25690–25707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, B. Nifty News: Dolce & Gabbana’s Historic NFTs, ‘26 Minute’ CryptoPunk Flip, FTX Spammed. Cointelegraph [Online], 7 September 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/nifty-news-dolce-gabbana-s-historic-nfts-26-minute-cryptopunk-flip-ftx-spammed (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Yorio, J. What NFT Sales Mean for Digital Real Estate. CoinDesk [Online], 17 March 2021. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2021/03/17/what-nft-sales-mean-for-digital-real-estate/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Roose, K. Buy This NFT Column on the Blockchain! The New York Times [Online], 30 June 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/technology/nft-column-blockchain.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Thomas, D. Dolce & Gabbana Sets $6 Million Record for Fashion NFTs. The New York Times [Online], 4 October 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/04/style/dolce-gabbana-nft.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Haig, S. Chinese Artist Showcases NFT Real Estate at Alibaba-SPONSORED innovation Festival. Cointelegraph [Online], 19 July 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/chinese-artist-showcases-nft-real-estate-at-alibaba-sponsored-innovation-festival (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Lyu, J. The Metaverse will Change the Paradigm of Content Creation. Cointelegraph [Online], 20 March 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/the-metaverse-will-change-the-paradigm-of-content-creation (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Quarmby, B. Alibaba Launches NFT Marketplace for Copyright Trading. Cointelegraph [Online], 17 August 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/alibaba-launches-nft-marketplace-for-copyright-trading (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Olsen, K. Children of Famous Fashion Brands Are Going Their Own Ways. The New York Times [Online], 22 February 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/22/style/italian-family-businesses-milan-fashion-week.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Blenkinsop, C. Blockchain Platform to Allow Users to Trade Gold for Virtual Currencies. Cointelegraph [Online], 1 August 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-platform-to-allow-users-to-trade-gold-for-virtual-currencies (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Breckenridge, G. Unlocking Cultural Markets with Blockchain: Web3 Brands and the Decentralized Renaissance. Cointelegraph Magazine [Online], 1 June 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/magazine/blockchain-web3-brands-decentralized-renaissance/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Baydakova, A. Overstock’s Medici Ventures Invests in Wine-Tracking Blockchain Startup. CoinDesk [Online], 4 October 2018. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2018/10/04/overstocks-medici-ventures-invests-in-wine-tracking-blockchain-startup/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Marshall, A. Riding Hermès to Record Revenue. The Wall Street Journal [Online], 15 September 2022. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/hermes-axel-dumas-ceo-biggest-us-store-new-york-11663007439 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Zhao, W. Blockchain Water Purifier? New China Mobile Appliance Earns You Tokens. CoinDesk [Online], 8 January 2019. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2019/01/08/blockchain-water-purifier-new-china-mobile-appliance-earns-you-tokens/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Milev, A. Innovation Marketplaces, Explained. Cointelegraph [Online], 13 March 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/explained/innovation-marketplaces-explained (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Steele, A. Martha Stewart Does NFTs—Jack-o’-Lantern Art and a Seductive Selfie. The Wall Street Journal [Online], 19 October 2021. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/martha-stewart-does-nftsjack-o-lantern-art-and-a-seductive-selfie-11634634001 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Wolfson, R. Reinventing Yourself in the Metaverse through Digital Identity. Cointelegraph [Online], 11 August 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/reinventing-yourself-in-the-metaverse-through-digital-identity (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Tripathi, A. NFTs Can Bring the Real World On-Chain. CoinDesk [Online], 17 March 2021. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2021/03/17/nfts-can-bring-the-real-world-on-chain/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Nikolskaia, K.; Snegireva, D.; Minbaleev, A. Development of the Application for Diploma Authenticity Using the Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT & QM & IS), Sochi, Russia, 23–27 September 2019; pp. 558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Jirgensons, M.; Kapenieks, J. Blockchain and the Future of Digital Learning Credential Assessment and Management. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 20, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampora, G.; Alghazzawi, D.; Hagras, H.; Vitiello, A. An interval type-2 fuzzy logic based framework for reputation management in Peer-to-Peer e-commerce. Inf. Sci. 2016, 333, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.-C. Blockchain-Based Real Estate Market: One Method for Applying Blockchain Technology in Commercial Real Estate Market. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Blockchain, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–17 May 2019; pp. 528–535. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Contemporary Strategy Analysis, 10th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Partz, H. Chinese e-Commerce Giant JD.com Drops NFT Series on Its Own Blockchain. Cointelegraph [Online], 20 October 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/chinese-e-commerce-giant-jd-com-drops-nft-series-on-its-own-blockchain (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Hernández, O. Boson Protocol Seeks to Blend Physical and Digital Marketplaces in the Metaverse. Cointelegraph [Online], 18 November 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/boson-protocol-seeks-to-blend-physical-and-digital-marketplaces-in-the-metaverse (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Sharpe, K. Blockchain E-Commerce Platform Allows Shoppers to Purchase Directly from Manufacturers. Cointelegraph [Online], 18 October 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-e-commerce-platform-allows-shoppers-to-purchase-directly-from-manufacturers (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Betz, B. A16z Leads $14M Funding Round for New E-Commerce Platform from Twitch Co-Founder. CoinDesk [Online], 11 October 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2022/10/11/a16z-leads-14m-funding-round-for-new-e-commerce-platform-from-twitch-co-founder/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Kirimi, A. eBay Acquires KnownOrigin, Expanding Its Foray into NFTs and Blockchain [Online], 22 June 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/ebay-acquires-knownorigin-expanding-its-foray-into-nfts-and-blockchain (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Cointelegraph. Restoring Data Back to its Owners with Blockchain. Cointelegraph [Online], 8 January 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/restoring-data-back-to-its-owners-with-blockchain (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Wolfson, R. Blockchain Metaverse Ecosystems Gain Traction as Brands Create Digital Experiences. Cointelegraph [Online], 23 January 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-metaverse-ecosystems-gain-traction-as-brands-create-digital-experiences (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Thompson, C. Metaverse Fashion Week: 70 Brands Do Their Best to Showcase Style in Decentraland. CoinDesk [Online], 24 March 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/tech/2022/03/24/metaverse-fashion-week-70-brands-do-their-best-to-showcase-style-in-decentraland/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Alexandre, A. Overstock’s tZERO Receives Patent for ‘Crypto Integration Platform’. Cointelegraph [Online], 8 January 2019. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/overstocks-tzero-receives-patent-for-crypto-integration-platform (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Jansen, S. Modeled after Amazon, This Platform Is Building the Bridge between DeFi and e-Commerce. Cointelegraph [Online], 16 September 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/modeled-after-amazon-this-platform-is-building-the-bridge-between-defi-and-e-commerce (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Paton, E. Blockchain Could Work for Luxury, too. The New York Times [Online], 19 November 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/fashion/news/blockchain-luxury-ethereum-consensys.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Wright, T. DLT Tracking Partnership to Fight Fake Diamonds in China. Cointelegraph [Online], 26 August 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/dlt-tracking-partnership-to-fight-fake-diamonds-in-china (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Partz, H. Report: Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior Owner Develops DLT Project with ConsenSys and Azure. Cointelegraph [Online], 26 March 2019. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/report-louis-vuitton-christian-dior-owner-develops-dlt-project-with-consensys-and-azure (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Donnelly, J. Identity Startup Netki to Launch SSL Certificate for Blockchain. CoinDesk [Online], 16 May 2016. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2016/05/16/identity-startup-netki-to-launch-ssl-certificate-for-blockchain/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Avan-nomayo, O. Corporate Brands Target NFTs, and Adoption Continues to Skyrocket. Cointelegraph [Online], 30 August 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/corporate-brands-target-nfts-and-adoption-continues-to-skyrocket (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Malaeb, J. The Metaverse is Creating a New Virtual Marketplace for Retail Brands. Cointelegraph [Online], 27 January 2023. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/the-metaverse-is-creating-a-new-virtual-marketplace-for-retail-brands (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Lyu, J. In the Economy 3.0, Metaverses Will Create Jobs for Millions. Cointelegraph [Online], 29 May 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/in-the-economy-3-0-metaverses-will-create-jobs-for-millions (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Robson, W. ‘Does Radio Ring a Bell?’: How the Metaverse Will Change Society. CoinDesk [Online], 25 May 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/layer2/metaverseweek/2022/05/25/does-radio-ring-a-bell-how-the-metaverse-will-change-society/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Belchior, R.; Vasconcelos, A.; Guerreiro, S.; Correia, M. A Survey on Blockchain Interoperability: Past, Present, and Future Trends. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotey, S.D.; Tchao, E.T.; Ahmed, A.-R.; Agbemenu, A.S.; Nunoo-Mensah, H.; Sikora, A.; Welte, D.; Keelson, E. Blockchain interoperability: The state of heterogenous blockchain-to-blockchain communication. IET Commun. 2023, 17, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, B. eBay Drops First NFT Collection to Non-Crypto Mainstream Buyers [Online], 24 May 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/ebay-drops-first-nft-collection-to-non-crypto-mainstream-buyers (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- van der Lans, S. Circling back to Blockchain’s Originally Intended Purpose: Timestamping. Cointelegraph [Online], 7 February 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/circling-back-to-blockchain-s-originally-intended-purpose-timestamping (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Jeffries, D. It’s 2031. This Is the World That Crypto Created. CoinDesk [Online], 21 May 2021. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2021/05/21/its-2031-this-is-the-world-that-crypto-created/ (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. An Overview of Blockchain Technology: Architecture, Consensus, and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress), Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, G.A. The market for ‘lemons’: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In Uncertainty in Economics: Readings and Exercises; Diamond, P.A., Rothschild, M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Balachander, S.; Liu, Y.; Stock, A. An Empirical Analysis of Scarcity Strategies in the Automobile Industry. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 1623–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierl, H.; Plantsch, M.; Schweidler, J. Scarcity effects on sales volume in retail. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2008, 18, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avan-nomayo, O. Forget Lambos, NFTs Are the New Crypto Status Symbol. Cointelegraph [Online], 26 August 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/forget-lambos-nfts-are-the-new-crypto-status-symbol (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasalou, A.; Joinson, A.; Bänziger, T.; Goldie, P.; Pitt, J. Avatars in social media: Balancing accuracy, playfulness and embodied messages. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrat, A.A.; Schelen, O.; Andersson, K. A Survey of Blockchain From the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 117134–117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W. Decentralization Revolutionizes the Creator’s Economy, but What Will It Bring? Cointelegraph [Online], 19 February 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/decentralization-revolutionizes-the-creator-s-economy-but-what-will-it-bring (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Haig, S. Wall St Veteran Launches Crypto-Powered Social Network and Marketplace. Cointelegraph [Online], 7 May 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/wall-st-veteran-launches-crypto-powered-social-network-and-marketplace (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Herrera, S. Metaverse Seems Poised to Spawn a New Economy, Says Activate CEO. The Wall Street Journal [Online], 26 October 2022. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/metaverse-seems-poised-to-spawn-a-new-economy-says-activate-ceo-11666741219 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Callon-butler, L. Megan Kaspar: Meta-a-Porter Fashion. CoinDesk [Online], 31 May 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2022/05/31/megan-kaspar-meta-a-porter-fashion/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Chin, M. In Luxury, What’s Next? The New York Times [Online], 19 November 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/fashion/luxury-retail-technology.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Rodrigues, F. PayPal stablecoin: What it could mean for payments. Cointelegraph [Online], 29 January 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/paypal-stablecoin-what-it-could-mean-for-payments (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Yorio, J.; Hungate, Z. The Metaverse Will Make Gamers of Us All. CoinDesk [Online], 23 May 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/layer2/metaverseweek/2022/05/23/the-metaverse-will-make-gamers-of-us-all/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Powers, B. Permission.io Has Quietly Raised $50M to Make Advertising Personal and Data Private. CoinDesk [Online], 29 September 2020. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2020/09/29/permissionio-has-quietly-raised-50m-to-make-advertising-personal-and-data-private/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Doyle, E. Can Cryptocurrency Create a New Niche in Music Streaming? Cointelegraph [Online], 11 November 2019. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/can-cryptocurrency-create-a-new-niche-in-music-streaming (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Blenkinsop, C. How DeFi Can Improve the e-Commerce Sector. Cointelegraph [Online], 18 November 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/how-defi-can-improve-the-e-commerce-sector (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Koay, K.Y.; Tjiptono, F.; Teoh, C.W.; Memon, M.A.; Connolly, R. Social Media Influencer Marketing: Commentary on the Special Issue. J. Internet Commer. 2023, 22 (Suppl. S1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. Virtual Worlds, Real-Life Use Cases: How Web2 and Web3 Tackled the Metaverse at CES 2023. CoinDesk [Online], 10 January 2023. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/web3/2023/01/10/virtual-worlds-real-life-use-cases-how-web2-and-web3-tackled-the-metaverse-at-ces-2023/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Sephton, C. Q&A: How Is This Crypto Platform Helping Big Brands Market to Consumers? Cointelegraph [Online], 29 April 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/qa-how-is-this-crypto-platform-helping-big-brands-market-to-consumers (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Lova, V. How to Get Paid for Your Web Search: A Startup to Give Data Control Back to Users. Cointelegraph [Online], 15 February 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/how-to-get-paid-for-your-web-search-a-startup-to-give-data-control-back-to-users (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Huillet, M. Chinese Retail Giant JD.com Launches Enterprise Blockchain-as-a-Service Platform. Cointelegraph [Online], 17 August 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/chinese-retail-giant-jdcom-launches-enterprise-blockchain-as-a-service-platform (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Higgins, S. Boston Fed: Bitcoin Could Be Reducing Online Shopping Costs. CoinDesk [Online], 17 September 2014. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2014/09/16/boston-fed-bitcoin-could-be-reducing-online-shopping-costs/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Rojko, M. The First and Most Reputable BTC Escrow Is for Sale. Cointelegraph [Online], 25 December 2015. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/the-first-and-most-reputable-btc-escrow-is-for-sale (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Buck, J. New Platform Leverages Blockchain Infrastructure to Create, Rent, Sell 3D Content. Cointelegraph [Online], 15 August 2017. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/new-platform-leverages-blockchain-infrastructure-to-create-rent-sell-3d-content (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Milionis, J.; Hirsch, D.; Arditi, A.; Garimidi, P. A Framework for Single-Item NFT Auction Mechanism Design. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.11293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbaan, E. The Elon Effect: How Musk’s Tweets Move Crypto Markets. CoinDesk [Online], 14 December 2021. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/layer2/culture-week/2021/12/14/the-elon-effect-how-musks-tweets-move-crypto-markets/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Arthur, W.B. The Second Economy. McKinsey Quaterly [Online], 1 October 2011. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-second-economy#/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Marshall, A. How Social E-Commerce Can Solve Problems of Decentralized Markets. Cointelegraph [Online], 14 September 2016. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/how-social-e-commerce-can-solve-problems-of-decentralized-markets (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Magas, J. Digital Yuan CBDC Momentum Grows as More Chinese Firms Get to Testing. Cointelegraph [Online], 19 July 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/digital-yuan-cbdc-momentum-grows-as-more-chinese-firms-get-to-testing (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Peng, T. Chinese City Issues Post-Pandemic Consumer Vouchers on the Blockchain. Cointelegraph [Online], 22 June 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/chinese-city-issues-post-pandemic-consumer-vouchers-on-the-blockchain (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Alexandre, A. FomoHunt Becomes First Merchant to Accept Huobi Tokens as Payment. Cointelegraph [Online], 22 August 2019. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/fomohunt-becomes-first-merchant-to-accept-huobi-tokens-as-payment (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Dale, B. Coinbase’s Merchant App Hits $50 Million in Volume Since 2018 Launch. CoinDesk [Online], 23 May 2019. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2019/05/23/coinbases-merchant-app-hits-50-million-in-volume-since-2018-launch/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Ogundeji, O. More Attempts to Bring E-Commerce to World’s Two Billion Unbanked. Cointelegraph [Online], 15 September 2017. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/more-attempts-to-bring-e-commerce-to-worlds-two-billion-unbanked- (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Leung, A. Purse.io Fights for Its Share in E-Commerce, Launches Pre-Order Service. Cointelegraph [Online], 25 May 2016. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/purseio-fights-for-its-share-in-e-commerce-launches-pre-order-service (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Castro, F. Friendly Fraud and the Failure of Chargeback Protections. Cointelegraph [Online], 2 January 2020. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/friendly-fraud-and-the-failure-of-chargeback-protections (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Nelson, D. UPS Ships Beef to Japan, Tracked and Monitored Using Blockchain Tech. CoinDesk [Online], 12 November 2019. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2019/11/12/ups-ships-beef-to-japan-tracked-and-monitored-using-blockchain-tech/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Egorova, K. Blockchain Startup Develops an Uber-like App for Parcel Shipment. Cointelegraph [Online], 5 June 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-startup-develops-an-uber-like-app-for-parcel-shipment (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Sinclair, S. Blockchain ID Solution Aims to Tackle Spike in Delivery Fraud Amid Coronavirus Measures. CoinDesk [Online], 29 May 2020. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/tech/2020/05/29/blockchain-id-solution-aims-to-tackle-spike-in-delivery-fraud-amid-coronavirus-measures/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Gamerman, E. Reese Witherspoon and Gwyneth Paltrow Push for Crypto Sisterhood. The Wall Street Journal [Online], 11 March 2022. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/reese-witherspoon-and-gwyneth-paltrow-push-for-crypto-sisterhood-11647017051 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Ahamad, S.S.; Nair, M.; Varghese, B. A survey on crypto currencies. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Advances in Computer Science, NCR, India, 13–14 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amri, R.; Zakaria, N.H.; Habbal, A.; Hassan, S. Cryptocurrency adoption: Current stage, opportunities, and open challenges. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Res. (IJACR) 2019, 9, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsop, C. Crypto Payment Gateway Offers Low Withdrawal Fees. Cointelegraph [Online], 13 December 2019. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/crypto-payment-gateway-offers-low-withdrawal-fees (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Baydakova, A. Hodl Hodl Wants You to Clone Its Bitcoin Exchange. CoinDesk [Online], 14 September 2019. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2019/09/14/hodl-hodl-wants-you-to-clone-its-bitcoin-exchange/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Allison, I. IBM Makes Another Blockchain Identity Play with Health Data App. CoinDesk [Online], 6 September 2018. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2018/09/06/ibm-makes-another-blockchain-identity-play-with-health-data-app/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Bakursky, N. Startup Aims to Make Online Shopping Easier and Sharing Personal Data Safer. Cointelegraph [Online], 11 March 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/startup-aims-to-make-online-shopping-easier-and-sharing-personal-data-safer (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Floyd, D. Amazon Sees Bitcoin Use Case in Data Marketplaces. CoinDesk [Online], 17 April 2018. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2018/04/17/amazon-sees-bitcoin-use-case-in-data-marketplaces/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Wilser, J. Virtual Beers and Digital Orgasms: Welcome to the Age of Metaverse Commerce. CoinDesk [Online], 8 March 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/layer2/2022/03/08/virtual-beers-and-digital-orgasms-welcome-to-the-age-of-metaverse-commerce/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Martin, J. YouTube boxer Logan Paul Turns Himself into an NFT Pokemon card. Cointelegraph [Online], 5 February 2021. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/youtube-boxer-logan-paul-turns-himself-into-an-nft-pokemon-card (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Wolfson, R. Blockchain-Enabled Digital Fashion Creates New Business Models for Brands. Cointelegraph [Online], 24 January 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-enabled-digital-fashion-creates-new-business-models-for-brands (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Reguerra, E. Shopify Bitcoin Payments Integration Triggers Legal Questions from the Community. Cointelegraph [Online], 8 April 2022. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/shopify-bitcoin-payments-integration-triggers-legal-questions-from-the-community (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Mühle, A.; Grüner, A.; Gayvoronskaya, T.; Meinel, C. A survey on essential components of a self-sovereign identity. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 30, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyskind, G.; Nathan, O.; Pentland, A. Decentralizing Privacy: Using Blockchain to Protect Personal Data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–22 May 2015; pp. 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Stokkink, Q.; Pouwelse, J. Deployment of a Blockchain-Based Self-Sovereign Identity. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conferences on Internet of Things, Green Computing and Communications, Cyber, Physical and Social Computing, Smart Data, Blockchain, Computer and Information Technology, Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018; pp. 1336–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.; Heumüller, E. Ansatz für ein faires Beteiligungsmodell am Datenerlös. In Marktforschung für Die Smart Data World: Chancen, Herausforderungen und Grenzen; Keller, B., Klein, H.-W., Wachenfeld-Schell, A., Wirth, T., Eds.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, T.; Gai, K.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. RAC-Chain: An Asynchronous Consensus-based Cross-chain Approach to Scalable Blockchain for Metaverse. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, A. Japanese E-Commerce Giant Rakuten To Launch Its Own Cryptocurrency. Cointelegraph [Online], 27 February 2018. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/news/japanese-e-commerce-giant-rakuten-to-launch-its-own-cryptocurrency (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Menard, C.; Shirley, M.M. Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Web3: Exploring Decentralized Technologies and Applications for the Future of Empowerment and Ownership. Blockchains 2023, 1, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaria, A.; Ekblaw, A.; Vieira, T.; Lippman, A. MedRec: Using Blockchain for Medical Data Access and Permission Management. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Open and Big Data, Vienna, Austria, 22–24 August 2016; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Chu, W.C.-C. Digital Asset Management with Distributed Permission over Blockchain and Attribute-Based Access Control. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Services Computing (IEEE SCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–7 July 2018; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamae, T.; Nishimaki, S.; Nakamura, M.; Fukuoka, T.; Morinaga, M. Advanced Ledger: Supply Chain Management with Contribution Trails and Fair Reward Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain, Espoo, Finland, 22–25 August 2022; pp. 435–442. [Google Scholar]

| Content Analysis Process Steps | Analysis According to Our Research Approach |

|---|---|

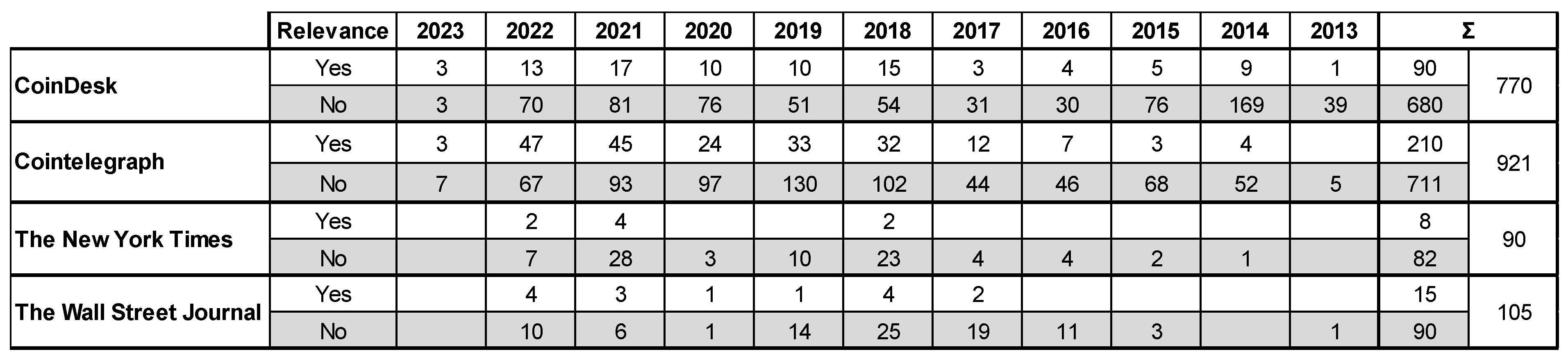

| Building a deductive coding frame | The main (structuring) categories of the coding frame are derived from our research aim, i.e., the e-commerce value chain steps. These concept-driven categories are based on the e-commerce value chain of Wirtz [43] and comprises two hierarchical levels, i.e., primary value chain steps as the main categories and their subdimensions as subcategories. The value chain focuses on the question of how e-commerce is conducted [1]. The value chain is a tool to understand the influence of IT on organisations [16]. It is, therefore, suitable to examine which parts of conducting commerce electronically might be affected by BCT usage. Furthermore, we base our concept-driven categories on the e-commerce value chain of Wirtz [43] for two reasons. First, the originally introduced value chain concept by Porter [49] tailored to manufacturing companies has been adapted to e-commerce already. Second, academic papers (e.g., [15,105,106]) have used single or multiple of the adapted business models including their value chains (cf. 4C-Net model) by Wirtz (e.g., [43,44]) already as a theoretical basis for further analyses. We use the e-commerce value chain as presented in Figure 1 apart from the value chain step “completion/price-setting”. As all the main categories, i.e., first-level categories, should only cover one aspect, we split this step into “completion” comprising contract finalisation and price determination, and “settlement” comprising payment handling and distribution. Furthermore, we have added category definitions, anchoring examples, and coding rules in the final coding frame. |

| Building inductive categories during trial coding | The categories on the third and final level of the coding frame are developed based on data. Therefore, we selected half of the material reflecting the full diversity of our data, i.e., material from all four news outlets over the whole time period, dealing with various topics according to the headlines. Based on this material, we conducted a trial coding, built categories, and determined anchoring examples for these newly derived categories. The coding process followed a sequential approach until saturation was reached as introduced by Schreier [104]: (1) read material until a relevant passage is found; (2) check whether it fits an existing data-drive subcategory; (3) either subsume it under the existing subcategory or create a new subcategory. All the steps were conducted manually using the qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA (https://www.maxqda.com/, accessed on 20 June 2024). |

| Revising the coding frame | The saturation of the coding frame was determined by the fact that no new categories were created after analysing new articles. In our trial coding, we already reached saturation after approximately 60% of the trial coding material. Some categories were stabilised at an early stage while the distinction of others was more challenging. To ensure validity (i.e., ensure the categories describe the material in an adequate way), in the next step we revised the coding frame and its assigned codes in a team of two researchers. Thereby, we determined category definitions, anchoring examples, and coding rules for the data-driven categories as well. Afterwards, the complete data set used for the trial coding was coded another time based on the final third-level categories to ensure intra-coder reliability. |

| Main analysis | During the main analysis, the remaining material is coded based on the finalised coding frame. |

| Presenting and interpreting the findings | Finally, we present the findings by proposing 41 BCT application domains in the e-commerce VC (according to the data-driven categories), which are described and illustrated through quotes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Witt, J.; Schoop, M. Blockchain Technology Application Domains along the E-Commerce Value Chain—A Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles. Blockchains 2024, 2, 234-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/blockchains2030012

Witt J, Schoop M. Blockchain Technology Application Domains along the E-Commerce Value Chain—A Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles. Blockchains. 2024; 2(3):234-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/blockchains2030012

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitt, Josepha, and Mareike Schoop. 2024. "Blockchain Technology Application Domains along the E-Commerce Value Chain—A Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles" Blockchains 2, no. 3: 234-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/blockchains2030012

APA StyleWitt, J., & Schoop, M. (2024). Blockchain Technology Application Domains along the E-Commerce Value Chain—A Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles. Blockchains, 2(3), 234-264. https://doi.org/10.3390/blockchains2030012