How Do French Adults Consume Their Dairy Foods? A Characterisation Study Using the INCA3 Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

- (i)

- First dimension: intakes.

- (ii)

- Second dimension: “eaten” vs. “drunk”.

- (iii)

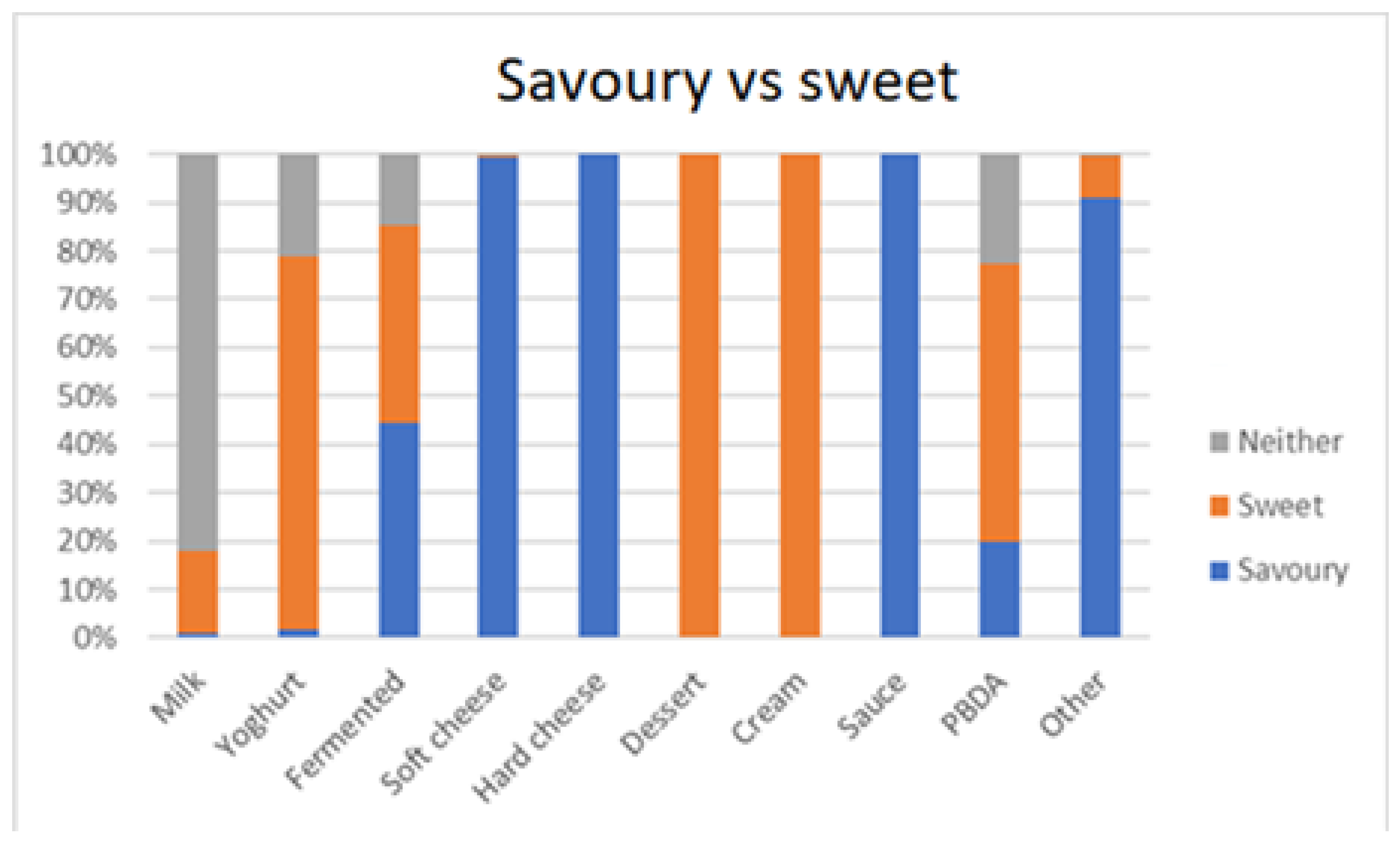

- Third dimension: “savoury” vs. “sweet”.

- (iv)

- Fourth dimension: “combined with other foods” vs. “by itself”.

- (v)

- Fifth dimension: time of day of the consumption (in hours, from 0 to 23).

- (vi)

- Sixth dimension: “meal” vs. “snack”.

3. Results

3.1. First Dimension: Intakes

3.2. Eating Patterns

3.2.1. Second Dimension: “Eaten” vs. “Drunk”

3.2.2. Third Dimension: “Savoury” vs. “Sweet”

3.2.3. Fourth Dimension: “In Combination with Other Foods” vs. “By Itself”

3.2.4. Fifth Dimension: Time of Day

3.2.5. Sixth Dimension: “Meals” vs. “Snacks”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| INCA | French Individual and National Survey Consumption (études Individuelles Nationales des Consommations Alimentaires) |

| Kcal | Kilocalories |

| kJ | Kilojoules, 1 Kcal = 4.186 kJ. |

| PBDA | Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives |

| PNNS | French National Nutrition and Health Program (Programme National Nutrition Santé) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Rozenberg, S.; Body, J.-J.; Bruyère, O.; Bergmann, P.; Brandi, M.L.; Cooper, C.; Devogelaer, J.-P.; Gielen, E.; Goemaere, S.; Kaufman, J.-M.; et al. Effects of Dairy Products Consumption on Health: Benefits and Beliefs—A Commentary from the Belgian Bone Club and the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 98, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, M.E.; Ribes, A.T.; Reynolds, R.; Kliem, K.; Stergiadis, S. A comparative assessment of the nutritional composition of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives available for sale in the UK and the implications for consumers’ dietary intakes. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Falvo, M.J. Protein—Which is best? J. Sports Sci. Med. 2004, 3, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian, D. Dairy Foods, Obesity, and Metabolic Health: The Role of the Food Matrix Compared with Single Nutrients. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 917S–923S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, A.M. Dairy products in global public health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1212S–1216S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunick, M.H.; Van Hekken, D.L. Dairy Products and Health: Recent Insights. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 9381–9388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaiano, D.A.; Hutkins, R.W. Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.R.; Hutkins, R. Yogurt and other fermented foods as sources of health-promoting bacteria. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Das, P.P.; Kambhampati, S.B.S. Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis. JOIO 2023, 57, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereford, T.; Kellish, A.; Samora, J.B.; Reid Nichols, L. Understanding the importance of peak bone mass. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Soc. N. Am. 2024, 7, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Lappe, J.; O’bRien, K.O.; Wang, D.D.; Sahni, S.; Weaver, C.M. Dairy intake and bone health across the lifespan: A systematic review and expert narrative. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 3661–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, F.; Bucci, C.; Iovino, P.; Ciacci, C. Consumption of milk and dairy products: Facts and figures. Nutrition 2017, 33, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, S.S.; Aparnathi, K.D.; Mehta, B.; Velpula, S. Goat Milk in Human Nutrition and Health—A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynal-Ljutovac, K.; Lagriffoul, G.; Paccard, P.; Guillet, I.; Chilliard, Y. Composition of goat and sheep milk products: An update. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 79, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. FAO Strategy on Climate Change 2022–2031; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022.

- Gaillac, R.; Marbach, S. The carbon footprint of meat and dairy proteins: A practical perspective to guide low carbon footprint dietary choices. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berners-Lee, M.; Hoolohan, C.; Cammack, H.; Hewitt, C.N. The relative greenhouse gas impacts of realistic dietary choices. Energy Policy 2012, 43, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, G.F.W. About the evolution of goat and sheep milk production. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 68, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, C.; Sherman, D.M. Sustainable goat production—Some global perspectives. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 89, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund, G. Dairy Processing Handbook; Tetra Pak Processing Systems: Lund, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; FAO. Milk and Milk Products, 2nd ed.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011.

- Almena-Aliste, M.; Mietton, B. Cheese Classification, Characterization, and Categorization: A Global Perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, R. Milk Analog: Plant based alternatives to conventional milk, production, potential and health concerns. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3005–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Etaio, I.; Valentin, D.; Dacremont, C.; Zannoni, M.; Tupasela, T.; Lilleberg, L.; Pérez-Elortondo, F.J. Effect of consumers’ origin on perceived sensory quality, liking and liking drivers: A cross-cultural study on European cheeses. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104047. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, O.M.; Badran, J.; Drake, M.A.; Reisner, M.; Moskowitz, H.R. Consumer acceptance of cow’s milk versus soy beverages: Impact of ethnicity, lactose tolerance and sensory preference segmentation. J. Sens. Stud. 2009, 24, 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Jin, D.; Ryan, G.S.; Jaeger, S.R. Sensory drivers of liking, emotions, conceptual and sustainability concepts in plant-based and dairy yoghurts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105077. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.; Francis, C.; Jenkins, E.L.; Schivinski, B.; Jackson, M.; Florence, E.; Parker, L.; Langley, S.; Lockrey, S.; Verghese, K.; et al. Consumer Perceptions of Food Packaging in Its Role in Fighting Food Waste. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzon, C.; Dougkas, A.; Memery, J.; Prigent, J.; Appleton, K.M. A qualitative study to explore and identify reasons for dairy consumption and non-consumption among young adults (18–30 years old) in the UK and France. J. Nutr. Sci. 2024, 13, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Bevelander, K.E.; Hermans, R.C.J. Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite 2015, 86, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racey, M.; Bransfield, J.; Capello, K.; Field, D.; Kulak, V.; Machmueller, D.; Preyde, M.; Newton, G. Barriers and Facilitators to Intake of Dairy Products in Adolescent Males and Females with Different Levels of Habitual Intake. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2017, 4, 2333794X1769422. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Deciphering a Meal. Daedalus 1972, 101, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. Good to Eat: Riddles of Food and Culture; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chinea, C.; Suárez, E.; Hernández, B. Meaning of food in eating patterns. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3331–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.; Skov Luridsen, D.; Gronow, J.; Khama, N.; Kjærnes, U.; Bøker Lund, T.; Mäkelä, J.; Niva, M. The food we eat. In Everyday Eating in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. A Comparative Study of Meal Patterns 1997–2012; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M. The Rituals of Dinner. The Origin, Evolution, Eccentricities and Meaning of Table Manners; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, J.P. The contemporary diet in France: “de-structuration” or from commensalism to “vagabond feeding”. Appetite 2002, 39, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfosse, C. La France et ses terroirs. Un siècle de débats sur les produits et leurs liens à l’espace. Pour 2012, 215–216, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A. “The Greatest Ordeal”: Using Biography to Explore the Victorian Dinner. Post-Mediev. Archaeol. 2010, 44, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, G. Dinner Is the Great Trial: Sociability and Service à la Russe in the Long Nineteenth Century. Eur. J. Food Drink Soc. 2021, 1, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Almerico, G.M. Food and identity: Food studies, cultural, and personal identity. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Stud. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S.E. Dairy Products: The Next Generation. Altering the Image of Dairy Products Through Technology. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, G.; Milán, M.J.; Lavín, M.P.; Theodoridis, A.; Morin, E.; Capote, J.; Thomas, D.L.; Francesconi, A.H.D.; Caja, G. Invited review: Current production trends, farm structures, and economics of the dairy sheep and goat sectors. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6715–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laila, A.; Topakas, N.; Farr, E.; Haines, J.; Ma, D.W.; Newton, G.; Buchholz, A.C. Barriers and facilitators of household provision of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives in families with preschool-age children. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5673–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.J.; White-Flynn, T.T.; Lyons, O.C.; Cronin, B.E.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Donovan, C.M.; Flynn, M.A.T. Is it yoghurt or is it a dessert? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, E69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, C.; Traill, W.B. Culture and food: A model of yoghurt consumption in the EU. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, D.A.; Durrant, C.; Elliott, J.; Givens, D.I.; Lovegrove, J.A. Diets containing the highest levels of dairy products are associated with greater eutrophication potential but higher nutrient intakes and lower financial cost in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence de la Transition Ecologique. 2021 Agribalyse Dataset, Synthese. Available online: https://entrepot.recherche.data.gouv.fr/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.57745/XTENSJ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Our World in Data. “Yearly per Capita Supply of Milk—Excluding Butter” [Based on Original Dataset Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Food Balances: Food Balances (-2013, Old Methodology and Population)”; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Food Balances: Food Balances (2010-)]” 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- European Dairy Association. EDA Factsheet ‘Daily Dairy Recommendations: Are We Eating Enough Dairy?’; European Dairy Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C.M. How sound is the science behind the dietary recommendations for dairy? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1217S–1222S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, I.A.; Elwood, P.C.; Hughes, J.; Jones, M.; Moore, F.; Sweetnam, P.M. A randomised controlled trial of the effect of the provision of free school milk on the growth of children. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1980, 34, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-C.; Szeto, I.M.Y.; Chen, L.-H.; Han, S.-F.; Li, Y.-J.; van Hekezen, R.; Qin, L.-Q. Dairy products consumption and metabolic syndrome in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, J. Meat–Egg–Dairy Consumption and Frailty among Chinese Older Adults: Exploring Rural/Urban and Gender Differences. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, E.; Casey, M.C.; Ward, M.; Hoey, L.; Hughes, C.F.; Mccarroll, K.; Cunningham, C.; Strain, J.J.; Mcnulty, H.; Molloy, A.M. Dairy intakes in older Irish aduts and effects on vitamin micronutrient status: Data from the TUDA study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapaj, A. Factors that influence milk consumption world trends and facts. Eur. J. Bus. Econ. Account. 2018, 6, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Charby, J.; Hébel, P.; Vaudaine, S. Les produits laitiers en France: Évolution du marché et place dans la diète. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2017, 52, S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Programme National Nutrition Santé 2019–2023 (PNNS4), Annexe 4; Ministère du Travail, de la Santé, des Solidarités et de Famille: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (ANSES). INCA 3: Evolution des Habitudes et Modes de Consommation, de Nouveaux Enjeux en Matière de Sécurité Sanitaire et de Nutrition. 2017. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/inca-3-evolution-des-habitudes-et-modes-de-consommation-de-nouveaux-enjeux-en-matiere-de (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (ANSES). Étude Individuelle Nationale des Consommations Alimentaires 3 (INCA 3); Avis de l’Anses—Rapport d’Expertise Collective; Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (ANSES): Maisons-Alfor, France, 2017.

- Ministère du Travail, de la Santé, des Solidarités et de Famille. Programme National Nutrition Santé (PNNS)—Professionnels. 2025. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr/prevention-en-sante/preserver-sa-sante/le-programme-national-nutrition-sante/article/programme-national-nutrition-sante-pnns-professionnels (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Tamime, A. Fermented milks: A historical food with modern applications—A review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Adamczyk, D.; Jaworska, D.; Affeltowicz, D.; Maison, D. Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives: Consumers’ Perceptions, Motivations, and Barriers—Results from a Qualitative Study in Poland, Germany, and France. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Arvisenet, G.; Gonera, A.; Myhrer, K.S.; Fifi, V.; Valentin, D. Meat replacer? No thanks! The clash between naturalness and processing: An explorative study of the perception of plant-based foods. Appetite 2022, 169, 105793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, R.M.; Worsley, A.; Timperio, A.; McNaughton, S.A. Characterizing eating patterns: A comparison of eating occasion definitions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.M.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Slavin, J.L. What Is a Snack, Why Do We Snack, and How Can We Choose Better Snacks? A Review of the Definitions of Snacking, Motivations to Snack, Contributions to Dietary Intake, and Recommendations for Improvement. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen, M.-L.; Reinivuo, H.; Tapanainen, H.; Hannila, M.-L.; Korhonen, T.; Pakkala, H. Snacks as an element of energy intake and food consumption. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatoire Economique de l’Achat Publique. Recommandation Nutrition Groupe d’étude des Marchès de Restauration Collective et Nutrition GEM-RCN. Version 2.0—July 2015; Observatoire Economique de l’Achat Publique: Paris, France, 2015.

- Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Programme National Nutrition Santé (PNNS) 2019–2023; Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ANSES. Ciqual Table de Composition Nutritionnelle des Aliments. 2016. Available online: https://ciqual.anses.fr/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- European Commission. MMO Economic Board. Milk Market Observatory. Annex: Milk Market Situation. 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/data-and-analysis/markets/overviews/market-observatories/milk_en (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Szczepańska, E.; Janota, B.; Wlazło, M.; Czapla, M. Eating behaviours, the frequency of consumption of selected food products, and selected elements of lifestyle among young dancers. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2021, 72, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cesbron-Lavau, E.; Lubrano-Lavadera, A.-S.; Braesco, V.; Deschamps, E. Fromages blancs, petits-suisses et laits fermentés riches en protéines. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2017, 52, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlioux, P. Histoire des laits fermentes. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2007, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpin, N. Le repas comme institution: Compte rendu d’une enquête exploratoire. Rev. Française Sociol. 1988, 29, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.D. Milk: The new sports drink? A Review. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2008, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Jebb, S.A.; Popkin, B.M. Patterns and trends of beverage consumption among children and adults in Great Britain, 1986–2009. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.S.; Parker, M.; Ameerally, A.; Drake, S.L.; Drake, M.A. Drivers of choice for fluid milk versus plant-based alternatives: What are consumer perceptions of fluid milk? J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 6125–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvera-Paredes, B.; Sánchez-Reséndiz, A.I.; Medina, D.I.; Espiricueta-Candelaria, R.S.; Serna-Saldívar, S.; Chuck-Hernández, C. Soft Tribology and Its Relationship with the Sensory Perception in Dairy Products: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 874763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupiec, B.; Revell, B. Speciality and artisanal cheeses today: The product and the consumer. Br. Food J. 1998, 100, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Silva, A.C.; Souza-Borges, P.K.D. Sensory characteristics, brand and probiotic claim on the overall liking of commercial probiotic fermented milks: Which one is more relevant? Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Jomaa, S.A.; Abd El-Wahed, A.; El-Seedi, H.R. The Many Faces of Kefir Fermented Dairy Products: Quality Characteristics, Flavour Chemistry, Nutritional Value, Health Benefits, and Safety. Nutrients 2020, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Eve, A.; Leclercq, H.; Berthelo, S.; Saulnier, B.; Oettgen, W.; Delarue, J. How much sugar do consumers add to plain yogurts? Insights from a study examining French consumer behavior and self-reported habits. Appetite 2016, 99, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, C.; Baudier, F.; Guilbert, P.; Carel, D.; Le Bihan, G.; Gautier, A.; Delamaire, C. Les repas des français: Résultats du baromètre santé nutrition 2002. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2004, 39, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, N.; De Henauw, S.; Beghin, L.; Cuenca-García, M.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Hallstrom, L.; Kafatos, A.; Kersting, M.; Manios, Y.; Marcos, A.; et al. Ready-to-eat cereals improve nutrient, milk and fruit intake at breakfast in European adolescents. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, Y.; Yardimci, H.; Ozcelik, A.O. Young adults’ milk consumption habits and knowledge about milk. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2017, 11, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Martín, E.; García-Escobar, E.; Ruiz de Adana, M.-S.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Peláez, L.; Caracuel, A.-M.; Bermúdez-Silva, F.-J.; Soriguer, F.; Rojo-Martínez, G.; Olveira, G. Comparison of the Effects of Goat Dairy and Cow Dairy Based Breakfasts on Satiety, Appetite Hormones, and Metabolic Profile. Nutrients 2017, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondin, S.A.; Goldberg, J.P.; Cash, S.B.; Griffin, T.S.; Economos, C.D. Factors Influencing Fluid Milk Waste in a Breakfast in the Classroom School Breakfast Program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 349–356.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagt, S.; Matthiessen, J.; Thyregod, C.; Kørup, K.; Biltoft-Jensen, A. Breakfast in Denmark. Prevalence of Consumption, Intake of Foods, Nutrients and Dietary Quality. A Study from the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.; Cowan, C.; Meehan, H.; O’Reilly, S. A conjoint analysis of Irish consumer preferences for farmhouse cheese. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Porcherot, C. Consumption context in consumer research: Methodological perspectives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 15, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, A. What Is a Recipe? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 719–738. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M.E.; Mistry, C.; Bourne, J.E.; Perrier, M.-J.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. A qualitative investigation of adults’ perceived benefits, barriers and strategies for consuming milk and milk products. Health Educ. J. 2015, 74, 364–378. [Google Scholar]

- Garabuau-Moussaoui, I. La cuisine des jeunes: Désordre alimentaire, identité générationnelle et ordre social. Anthropol. Food-Tradit. Identités Aliment. Locales 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Thompson, W.G.; Almasri, J.; Wang, Z.; Lakis, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Hensrud, D.D.; Frie, K.S.; Wirtz, M.J.; Murad, A.L.; et al. The effect of culinary interventions (cooking classes) on dietary intake and behavioral change: A systematic review and evidence map. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, H. The Relationships between Food Literacy, Health Promotion Literacy and Healthy Eating Habits among Young Adults in South Korea. Foods 2022, 11, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfosse, C. La diffusion mondiale de la consommation de fromage, de l’ingrédient de pizza au produit de terroir. Pour 2012, 215–216, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumey, G. La France, un plateau de fromages. Géographie 2012, 1544, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forwood, S.E. Solving the diet problem: Meals as food choice heuristics for behaviour change. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 64, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, B.; Duval, Q.; Girdhar, R.; Drozdzal, M.; Romero-Soriano, A. Learning to Substitute Ingredients in Recipes. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake by changing environments, policy and pricing: Restaurant-based research, strategies, and recommendations. Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Mullis, R.M. Environmental Interventions to Promote Healthy Eating: A Review of Models, Programs, and Evidence. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Mandracchia, F.; Tarro, L.; Llauradó, E.; Valls, R.M.; Solà, R. Interventions to Promote Healthy Meals in Full-Service Restaurants and Canteens: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, U.; Lorber, M.; Bolha, A.; Bahar, J.B.; Lavrič, M.; Turk, S.Š. Sustainability aspects of food and drinks offered in vending machines at Slovenian universities. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1439690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.; Fozard, T.; Kolokotroni, K.Z.; Marwood, J.; Evans, T.; Ells, L.J.; Burrows, T. Understanding eating behaviours, mental health and weight change in young adults: Protocol paper for an international longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabro, R.; Kemps, E.; Prichard, I.; Tiggemann, M. Vending machine backgrounds: Nudging healthier beverage choices. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, C.; van der Lans, I.A.; van Kleef, E.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Promoting healthy choices from vending machines: Effectiveness and consumer evaluations of four types of interventions. Food Policy 2018, 79, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Zerbini, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Scazzina, F.; Brighenti, F.; Lugli, G. How to improve food choices through vending machines: The importance of healthy food availability and consumers’ awareness. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Carrad, A.M.; Louie, J.C.; Milosavljevic, M.; Kelly, B.; Flood, V.M. Consumer support for healthy food and drink vending machines in public places. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar]

- Palascha, A.; Chang, B.P.I. Which messages about healthy and sustainable eating resonate best with consumers with low socio-economic status? Appetite 2024, 198, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Schweiger, D.; Clark, S. Dairy nutrition educational messages help increase dairy product knowledge, purchasing, and consumption. JDS Commun. 2024, 5, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohoff, E.; Perrar, I.; Jancovic, N.; Alexy, U. Age and time trends of dairy intake among children and adolescents of the DONALD study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3861–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbouys, L.; Méjean, C.; De Henauw, S.; Castetbon, K. Socio-economic and cultural disparities in diet among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witard, O.C.; Devrim-Lanpir, A.; McKinley, M.C.; Givens, D.I. Navigating the protein transition: Why dairy and its matrix matter amid rising plant protein trends. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yackobovitch-Gavan, M.; Phillip, M.; Gat-Yablonski, G. How Milk and Its Proteins Affect Growth, Bone Health, and Weight. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2017, 88, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 783 | Average Weight Consumed [g/Day] | Average Energy Intake [kcal/Day] | Average Energy Intake [kJ/day] |

|---|---|---|---|

| All dairy | 246 | 269 | 1126 |

| Soft dairy | 215 | 187 | 783 |

| Milk | 118 | 60 | 252 |

| Yoghurt | 63 | 54 | 227 |

| Fermented dairy | 15 | 18 | 75.3 |

| Soft cheese | 19 | 54 | 227 |

| Hard cheese | 12 | 45 | 187 |

| Dessert | 19 | 36 | 151 |

| Cream | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| Sauce | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| PBDA | 3 | 2 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franzon, C.; Dougkas, A.; Memery, J.; Appleton, K.M. How Do French Adults Consume Their Dairy Foods? A Characterisation Study Using the INCA3 Database. Gastronomy 2025, 3, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3040018

Franzon C, Dougkas A, Memery J, Appleton KM. How Do French Adults Consume Their Dairy Foods? A Characterisation Study Using the INCA3 Database. Gastronomy. 2025; 3(4):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3040018

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranzon, Caterina, Anestis Dougkas, Juliet Memery, and Katherine M. Appleton. 2025. "How Do French Adults Consume Their Dairy Foods? A Characterisation Study Using the INCA3 Database" Gastronomy 3, no. 4: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3040018

APA StyleFranzon, C., Dougkas, A., Memery, J., & Appleton, K. M. (2025). How Do French Adults Consume Their Dairy Foods? A Characterisation Study Using the INCA3 Database. Gastronomy, 3(4), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3040018