Efficiency of Orthopaedic Audits in a Level-1 Trauma Centre Using a Modified Clavien–Dindo Complications Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modified Classification System

2.2. Development and Implementation

2.3. Research Question and Data Recording

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications: A New Proposal with Evaluation in a Cohort of 6336 Patients and Results of a Survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; De Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; De Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications: Five-Year Experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, S.; Sugawara, Y.; Kaneko, J.; Yamashiki, N.; Kishi, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Kokudo, N.; Makuuchi, M. Systematic Grading of Surgical Complications in Live Liver Donors According to Clavien’s System. Transpl. Int. 2006, 19, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, A.B.; Weiser, T.G.; Berry, W.R.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Breizat, A.-H.S.; Dellinger, E.P.; Herbosa, T.; Joseph, S.; Kibatala, P.L.; Lapitan, M.C.M.; et al. A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permpongkosol, S.; Link, R.E.; Su, L.-M.; Romero, F.R.; Bagga, H.S.; Pavlovich, C.P.; Jarrett, T.W.; Kavoussi, L.R. Complications of 2,775 Urological Laparoscopic Procedures: 1993 to 2005. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodwell, E.R.; Pathy, R.; Widmann, R.F.; Green, D.W.; Scher, D.M.; Blanco, J.S.; Doyle, S.M.; Daluiski, A.; Sink, E.L. Reliability of the Modified Clavien-Dindo-Sink Complication Classification System in Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgery. JBJS Open Access 2018, 3, e0020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veen, M.R.; Lardenoye, J.W.; Kastelein, G.W.; Breslau, P.J. Recording and Classification of Complications in a Surgical Practice. Eur. J. Surg. 1999, 165, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riekert, M.; Kreppel, M.; Schier, R.; Zöller, J.E.; Rempel, V.; Schick, V.C. Postoperative Complications after Bimaxillary Orthognathic Surgery: A Retrospective Study with Focus on Postoperative Ventilation Strategies and Posterior Airway Space (PAS). J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guissé, N.F.; Stone, J.D.; Keil, L.G.; Bastrom, T.P.; Erickson, M.A.; Yaszay, B.; Cahill, P.J.; Parent, S.; Gabos, P.G.; Newton, P.O.; et al. Modified Clavien–Dindo–Sink Classification System for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2022, 10, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roye, B.D.; Fano, A.N.; Quan, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Garg, S.; Heffernan, M.J.; Poon, S.C.; Glotzbecker, M.P.; Fletcher, N.D.; Sturm, P.F.; et al. Modified Clavien–Dindo-Sink System Is Reliable for Classifying Complications Following Surgical Treatment of Early-Onset Scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2023, 11, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sink, E.L.; Beaulé, P.E.; Sucato, D.; Kim, Y.-J.; Millis, M.B.; Dayton, M.; Trousdale, R.T.; Sierra, R.J.; Zaltz, I.; Schoenecker, P.; et al. Multicenter Study of Complications Following Surgical Dislocation of the Hip. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2011, 93, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, A.F.; Bowerman, J.W.; Robinson, R.A.; Riley, L.H. Ectopic Ossification Following Total Hip Replacement. Incidence and a Method of Classification. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1973, 55, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, J.J.; Dahmen, J.; Emanuel, K.S.; Stufkens, S.A.S.; Kennedy, J.G.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J. The Frequency and Severity of Complications in Surgical Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 6962 Lesions. Cartilage 2023, 14, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorhies, J.S.; Hauth, L.; Garcia, S.; Roye, B.D.; Poon, S.; Sturm, P.F.; Glotzbecker, M.; Fletcher, N.D.; Stone, J.D.; Cahill, P.J.; et al. A New Look at Vertebral Body Tethering (VBT): Through the Modified Clavien-Dindo-Sink (mCDS) Classification. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2024, 44, e389–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolfi, D.; Oyekan, A.A.; Tang, M.Y.; Chen, S.R.; Como, C.J.; Dalton, J.; Gannon, E.J.; Jackson, K.L.; Bible, J.E.; Kowalski, C.; et al. Modified Clavien-Dindo-Sink Classification System for Operative Complications in Adult Spine Surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2024, 40, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasiak, M.; Piekut, M.; Ratajczak, K.; Waśko, M. Early Complications of Percutaneous K-Wire Fixation in Pediatric Distal Radius Fractures—A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2023, 143, 6649–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Rhee, J.; Sutherland, D.; Benjamin, C.; Engel, J.; Frazier, H. Surgical Complications After Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: The Initial 1000 Cases Stratified by the Clavien Classification System. J. Endourol. 2012, 26, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, S.R.; Whitty, S.; Flood, S.; Neoh, D.; Nunn, A.; Clegg, B.; Ng, S.K. Surgical Management of Pressure Ulcers in Spinal Cord Injury Patients. ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, S.; Blackburn, A. Modified Clavien-Dindo Classification for Microsurgical Breast Reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2024, 94, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou, C.; Hu, L.; Smith, T.O.; Hing, C.B. Hawthorne Effect on Surgical Studies. ANZ J. Surg. 2019, 89, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemons, K.; Bosch, M.; Coakeley, S.; Muzammal, B.; Kachra, R.; Ruzycki, S.M. Barriers and Facilitators of Following Perioperative Internal Medicine Recommendations by Surgical Teams: A Sequential, Explanatory Mixed-Methods Study. Perioper. Med. 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P.A.; Sanabria, J.R.; Strasberg, S.M. Proposed Classification of Complications of Surgery with Examples of Utility in Cholecystectomy. Surgery 1992, 111, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Golder, H.; Casanova, D.; Papalois, V. Evaluation of the Usefulness of the Clavien-Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications. Cir. Esp. Engl. Ed. 2023, 101, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS). Updated Surgical Competence and Performance Guide. Available online: https://www.surgeons.org/News/News/Updated-Surgical-Competence-and-Performance-Guide (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Birkmeyer, J.D.; Siewers, A.E.; Finlayson, E.V.A.; Stukel, T.A.; Lucas, F.L.; Batista, I.; Welch, H.G.; Wennberg, D.E. Hospital Volume and Surgical Mortality in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, J.H.; Gaski, G.E. Update on Venous Thromboembolism in Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, M.L.; Martín-Lorenzo, J.G.; Lirón-Ruiz, R.; Torralba-Martínez, J.A.; García-López, J.A.; Aguayo-Albasini, J.L. Perioperative Complications Following Bariatric Surgery According to the Clavien-Dindo Classification. Score Validation, Literature Review and Results in a Single-Centre Series. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Bai, B.; Ji, G.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q. Relationship between Clavien–Dindo Classification and Long-Term Survival Outcomes after Curative Resection for Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 60, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téoule, P.; Bartel, F.; Birgin, E.; Rückert, F.; Wilhelm, T.J. The Clavien-Dindo Classification in Pancreatic Surgery: A Clinical and Economic Validation. J. Investig. Surg. 2019, 32, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosma, E.; Pullens, M.J.J.; De Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A. The Impact of Complications on Quality of Life Following Colorectal Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study to Evaluate the Clavien–Dindo Classification System. Color. Dis. 2016, 18, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, R.S.; King, K.L.; Lewis, D.P.; Weaver, N.A.; Balogh, Z.J. Modifiability of Surgical Timing in Postinjury Multiple Organ Failure Patients. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Morrison, S.G.; Lade, J.A.; Haw, C.S. An Integrated Approach to Surgical Audit: Perspectives. ANZ J. Surg. 2011, 81, 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Definition | Examples of Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| I | Any deviation from normal post-operative course without the need for pharmacological, surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic treatment | IV fluids, antipyretics, anti-emetics, electrolytes, physiotherapy |

| II | Requiring pharmacological treatments other than those allowed in grade I | IV antibiotics, blood transfusions, parenteral nutrition |

| III | Requiring surgical or endoscopic treatment

| Return to theatre for washout of septic wound, gastrointestinal endoscopy, radiological angioembolisation |

| IV | Life-threatening complication requiring specialist intensive care management

| Admission to ICU for haemofiltration or ventilation |

| V | Patient mortality | n/a |

| Modified Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| Grade I | Any deviation from post-op course without the need for non-standard intervention. |

| Allowed regimens: Antiemetics, analgesics, antipyretics, electrolytes, and physiotherapy | |

| Grade II | Complication requiring pharmacological treatment (other than allowed drugs in grade I) |

| Examples: Blood transfusions, TPN, IV antibiotics | |

| Grade III | Requiring surgical, radiological or endoscopic intervention |

| III-A: NOT under general anaesthesia | |

| III-B: Under general anaesthesia | |

| Grade IV | Life threatening complication requiring immediate care |

| IV-A: Requiring pharmacological treatment on ward alone (+/− ICU outreach) | |

| IV-B: Requiring ICU admission (e.g., for inotropic support) | |

| IV-C: Requiring specialist ICU intervention (e.g., ECMO, haemofiltration, etc.) | |

| Grade V | Patient mortality |

| V-A: Expected or non-preventable | |

| V-B: Unexpected or preventable | |

| VTE | Additional classification for any complication, including a thromboembolic event (VTE/PE) |

| VTE-A: Prophylaxis was prescribed and in line with local guidelines | |

| VTE-B: Prophylaxis WAS NOT prescribed or WAS prescribed but not in line with local guidelines |

| Original CD Scale (Q2 2020–Q1 2021) | Modified CD Scale (Q2 2021–Q1 2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of audit presentations | 8 | 8 |

| Number of total complications | 176 | 165 |

| Number of complication cases presented at each meeting | 21.63 ± 3.2 | 20.63 ± 3.1 |

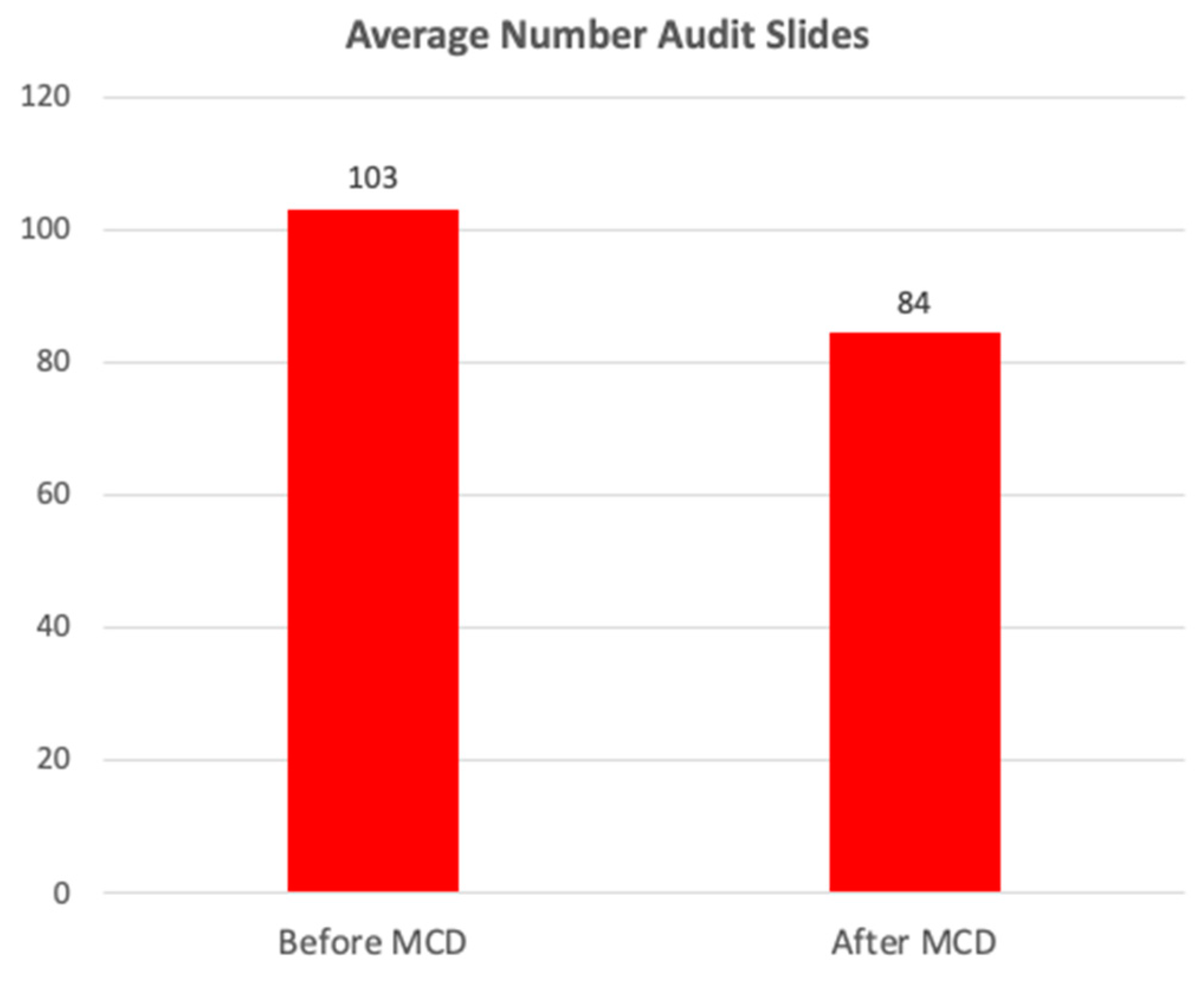

| Number of slides in each presentation | 103.13 ± 10.50 | 84.36 ± 3.35 * |

| Time spent for audit (mins) | 87.66 ± 13.80 | 71.72 ± 3.05 ^ |

| Proportion of audit time spent discussing complications (%) | 53 ± 4 | 37 ± 3 |

| Original CD Scale (Q2 2020–Q1 2021) | Modified CD Scale (Q2 2021–Q1 2022) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 20 | I | 23 |

| II | 45 | II | 40 |

| III | 70 | III A | 8 |

| IV | 16 | III B | 58 |

| V | 25 | IV A | 7 |

| IV B | 6 | ||

| IV C | 0 | ||

| V A | 6 | ||

| V B | 17 | ||

| Total | 176 | Total | 165 |

| VTE A | 32 | ||

| VTE B | 12 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talia, A.J.; Furness, N.; Liew, S.M. Efficiency of Orthopaedic Audits in a Level-1 Trauma Centre Using a Modified Clavien–Dindo Complications Classification. Complications 2024, 1, 14-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications1010004

Talia AJ, Furness N, Liew SM. Efficiency of Orthopaedic Audits in a Level-1 Trauma Centre Using a Modified Clavien–Dindo Complications Classification. Complications. 2024; 1(1):14-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications1010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalia, Adrian J., Nicholas Furness, and Susan M. Liew. 2024. "Efficiency of Orthopaedic Audits in a Level-1 Trauma Centre Using a Modified Clavien–Dindo Complications Classification" Complications 1, no. 1: 14-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications1010004

APA StyleTalia, A. J., Furness, N., & Liew, S. M. (2024). Efficiency of Orthopaedic Audits in a Level-1 Trauma Centre Using a Modified Clavien–Dindo Complications Classification. Complications, 1(1), 14-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications1010004