1. Introduction

This article aims to analyze a specific training experience designed for teachers to help them identify and mitigate AI biases in educational applications. The intervention was conducted in higher education contexts, involving university lecturers and postgraduate students enrolled in teacher-training programs in the Dominican Republic. The central purpose is to explore how such training can enhance educators’ ability to design fairer and more inclusive practices when using AI tools in the classroom, with a particular focus on developing skills for creating inclusive prompts and strategies that promote algorithmic equity and educational justice [

1,

2]. The conceptual foundation of this study rests on three complementary theoretical frameworks: algorithmic justice, which situates fairness as an ethical and structural imperative in automated systems [

3]; the TRIC model (Technology, Relationships, Interactions, and Context), which emphasizes the relational and communicative dimensions of digital practices [

4]; and algorithmic intersectionality, which reveals how overlapping social categories such as gender, ethnicity, and class shape algorithmic outcomes [

5,

6].

However, despite growing interest in ethical AI in education, empirical research shows teachers possess declarative knowledge of AI applications in education but demonstrate gaps in conceptual understanding of bias mechanisms, such as how models perpetuate inequalities based on race, gender, or socio-economic status [

7,

8]. For instance, surveys and qualitative analyses reveal that educators frequently overlook AI’s replication of societal biases in grading or intervention recommendations, attributing this to insufficient professional development [

2]. Literature consistently identifies formative deficiencies, with teachers calling for institutional support, clear policies, and training to enhance bias awareness and promote equitable AI use [

8,

9]. These studies emphasize that bridging knowledge gaps through professional development is essential for translating awareness into classroom practices that mitigate bias risks [

7,

10].

The literature on AI ethics and AI bias education delineates diverse teaching methods that integrate conceptual instruction with experiential and critical practice across teacher training contexts. These approaches aim to equip learners with foundational knowledge of ethical principles—such as fairness, transparency, accountability, and justice—and practical competencies for identifying, analyzing, and mitigating biases in AI systems deployed in educational settings [

11,

12].

Explicit ethics modules constitute a foundational method, often adapting bioethics frameworks to structure content around core values like beneficence and non-maleficence, progressing from technical literacy on training data biases to normative decision-making assessed via ethics rubrics or literacy scales [

11]. Case-based learning immerses participants in real-world scenarios, such as biased automated grading or predictive analytics disadvantaging marginalized students, typically facilitated in small groups to dissect stakeholder impacts and design alternatives [

13].

On the technical side, project- and design-based methods extend involve bias audits, dataset debiasing, or tool redesigns that link ethics to technical agency [

13]. In teacher education, these converge in hands-on workshops centered on prompt engineering, where educators test generative tools to detect stereotypes in outputs and refine inputs for fairness, complemented by case study analyses of discriminatory grading systems through group discussions and bias checklists [

14]. This study is based on a modular program that aims at integrate data literacy and ethical reasoning on task-based simulations allow diverse educators to co-create mitigation strategies via prompt design and appropriate input data selection [

15]. This approach emphasize human–AI collaboration to prevent perpetuation of inequities in classroom applications. The innovative aspect of our work lies in the application of dialogical reflection as a methodological approach to foster deeper understanding and critical engagement throughout the process.

Few empirical studies have examined how dialogic reflection concretely shapes educators’ awareness and bias-mitigation practices. These perspectives jointly inform our research questions and guide the interpretation of results, framing dialogic reflection as a pedagogical process that links ethical awareness, inclusivity, and technological agency. In this study, the term “agency” refers to educators’ capacity to act autonomously and critically in shaping the ethical use of AI tools, rather than merely adopting them as passive users. As AI becomes entrenched in classroom applications, educators act as pivotal agents of change by both detecting AI-driven inequities and shaping inclusive teaching practices. Educational empowerment is a key concept of this topic that signals the importance of arming both teachers and students with skills to critically analyze and challenge AI recommendations. The emphasis on digital literacy and ethical agency prepares educators to design inclusive prompts and teach students how to recognize and address bias—enabling them to act as advocates for fairness in technology-mediated learning environments. This perspective foregrounds equitable AI use as an ongoing practice, reliant on curiosity, dialogue, and the intentional examination of disparities in outcomes [

16,

17,

18].

In this way, it becomes necessary to emphasize the necessity of proactive bias identification, continuous monitoring of AI tools, and cross-sector collaboration—particularly between educators, developers, and policymakers—to establish robust ethical guidelines that underpin fair use of AI in education [

19]. The importance of practical strategies for prompt design is illustrated by recent literature reviews and applied recommendations [

17,

20]. Equipping educators with clear frameworks for constructing inclusive and unbiased prompts helps preempt AI outputs that inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes or misinformation. These actions not only raise awareness but furnish educators with tangible ways to counteract the reproduction of historical inequities, thus contributing to the iterative enhancement of AI education systems towards greater fairness for all students.

This kind of collaborative responsibility is echoed in findings from the OECD’s notes on Trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) in education [

17], which note how educators, EdTech developers, and regulators each play distinct yet interdependent roles in combating AI bias. For educators, vigilance is essential: not only in interpreting and contextualizing AI-generated outputs, but also in ensuring critical and ethical application that supplements, rather than substitutes, human judgment. Developers are expected to thoroughly audit algorithms for bias pre-deployment, and policymakers must enforce effective, transparent standards such as the EU’s mandated bias audits—collectively underpinning algorithmic justice across educational ecosystems [

17,

18,

21,

22].

The analysis is particularly framed within the theory of algorithmic justice, which applies the principle of equity to the design, implementation, and evaluation of automated systems [

3,

23]. This perspective situates algorithms as social configurations that, if not critically supervised, reproduce systemic biases embedded in broader societal structures [

24]. In the educational sphere, such biases manifest not only in AI outputs but also in important processes such as student evaluation, access to content, and classification, generating invisible exclusions that require a more profound ethical and sociocultural examination than typically addressed. To enrich this understanding, the TRIC model (Technology, Relationships, Interactions and Context), proposed by Bernal-Meneses, Marta-Lazo, and Gabelas-Barroso [

4], is incorporated to analyze digital practices from communicative, ethical, and situated perspectives. This model expands the usual individual skill-based training highlighted in some empirical studies [

25] by emphasizing the teacher’s role as a cultural mediator, confronting automated processes that would otherwise remain unquestioned.

Further advancing the discourse, our framework integrates insights from algorithmic intersectionality [

5,

6], which reveal how AI systems can reinforce inequalities intersecting ethnicity, gender, language, and class. This dimension addresses critiques from voices such as [

17,

18], who highlight the limitations of focusing narrowly on prompt engineering and ethical awareness without confronting structural power imbalances that underpin algorithmic biases. It also resonates with findings on digital exclusion affecting marginalized groups, including migrant students and non-hegemonic ethnicities [

5,

18,

25,

26,

27] who document how sociotechnical factors deepen inequities in AI-augmented education.

Finally, positioning AI ethics as the backbone of debates on justice and technological equity [

28,

29,

30], this framework proposes a comprehensive approach that moves beyond technical competencies to foster continuous critical reflection and systemic awareness in educator training. In this way, it complements and extends prior studies by demanding holistic educational policies and professional development programs that prepare teachers not only to mitigate technological bias but to actively promote social justice within AI-augmented learning environments. The novelty of our proposal lies precisely in transcending training models based on rapid prompt-engineering techniques or superficial checklists of ethical principles. Instead, our model positions dialogic reflection as the central mechanism through which educators interrogate the sociotechnical origins of bias, connect them to local inequities, and collaboratively craft context-sensitive mitigation strategies. This approach contrasts with technical-only interventions by emphasizing ethical agency, collective reasoning, and the sociohistorical roots of algorithmic injustice.

In line with the theory of algorithmic justice [

3,

23] and the critical models of digital literacy in education [

5,

6], dialogical reflection emerged in our intervention as a central component to transcend the mere technical identification of biases and move towards an ethical and situated understanding of AI use in educational contexts. Through collaborative dynamics and guided debate spaces [

20], teachers were able to recognize their own limitations and pre-existing biases in the use of technological tools, exposing assumptions and practices that could reproduce inequalities if left uncritically examined [

30]. This process strengthened their ability to connect the diversity and intersectionality of students with the functioning and outputs of algorithmic systems, understanding how certain configurations may favor or exclude specific student profiles. Finally, the dialogical interaction fostered a collective exploration of mitigation strategies and the redesign of inclusive prompts, incorporating frameworks such as the TRIC model [

4] and recent recommendations on teacher training for ethical AI use [

16,

18,

25], aiming to reinforce the role of teachers as critical mediators and agents of educational justice in the algorithmic era.

Regarding specific experiences on training teachers to identify and mitigate biases in generative AI in education reveal diverse approaches emphasizing ethical literacy, practical skills like prompt design, and reflective discussions. Several programs combine these elements, yet studies diverge in depth and focus needed in such training.

For instance, the Spanish National Institute for Educational Technologies and Teacher Training [

16] proposes a holistic professional development model that integrates AI literacy, ethical considerations aligned with EU regulations, and hands-on activities such as creating inclusive prompts and applying AI critically in lesson plans. This approach underscores active reflection forums fostering a community around ethical AI use, supporting educators as agents of fairness in AI-enabled classrooms.

Similarly, multimedia resources are designed to illustrate real classroom scenarios with generative AI, sensitizing teachers to both potential benefits and algorithmic risks, and reinforcing ethical awareness alongside technical skills. Sánchez et al. [

25] and Anwar [

31] emphasize experiential frameworks where teachers actively engage with multiple AI tools to identify biases through comparative analysis of outputs and iterative prompt engineering. Their work stresses ongoing bias auditing and data diversity as critical components, aligning with the practical focus of INTEF but with additional emphasis on systemic challenges such as data privacy.

On a more critical note, Vincent-Lancrin & Van der Vlies [

17] argue that training focused mainly on prompt engineering and technical mitigation may overlook deeper systemic biases embedded in AI datasets and algorithms. They warn that without embedding rigorous ethical engagement and critical pedagogical reflection, teacher training risks becoming superficial, potentially reinforcing inequities despite well-intended interventions.

Taking all those studies together, our intervention was based on two main steps to design teacher training activities on generative AI bias mitigation: first, a more practical, skills-based approach such as prompt engineering integrated with ethical awareness [

16,

25,

31]. Second, carry on training on a dialogic based method to stress the necessity of deep, continuous ethical reflection and systemic critique to avoid superficial adoption of GAI tools [

17,

32]. Both steps recognize educators’ crucial role in shaping fair and inclusive AI use in education but advocate that technical competence is not enough if we do not develop a collaborative and socially oriented ethical-pedagogical engagement. Subsequent sections explore educators’ attitudes toward AI ethics, their capacity-building needs for inclusive prompt design, and emerging references to Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) as a pedagogical resource, which are theoretically grounded in the frameworks outlined above.

2. Materials and Methods

The participants were 102 educators from higher education institutions, mainly university lecturers and postgraduate students specializing in Biology and Educational Innovation, participating voluntarily in a public professional development program. The pedagogical intervention designed to address discrimination biases in artificial intelligence (AI) was implemented as part of a series of teacher training courses for primary and secondary school educators, offered within the professional development programs of a public university in the Dominican Republic. The two cohorts were analyzed separately because disciplinary background influences how educators approach ethical decision-making and prompt-design practices. Prior studies in digital literacy and STEM education suggest that teachers’ epistemic frameworks shape the way they recognize and articulate algorithmic bias. For this reason, descriptive comparisons were included to identify whether disciplinary experience conditioned the salience of certain themes. This research follows qualitative design grounded in the principles of action research. Rather than observing pre-existing practices as in traditional ethnography, the study actively implemented an educational intervention—a teacher training program—and examined its effects on participants’ awareness and practices. The dual purpose of improving pedagogical action while simultaneously analyzing its outcomes aligns with action research orientation. The design thus combines intervention and reflection, enabling a situated understanding of how educators engage with ethical AI use and bias mitigation in real educational contexts.

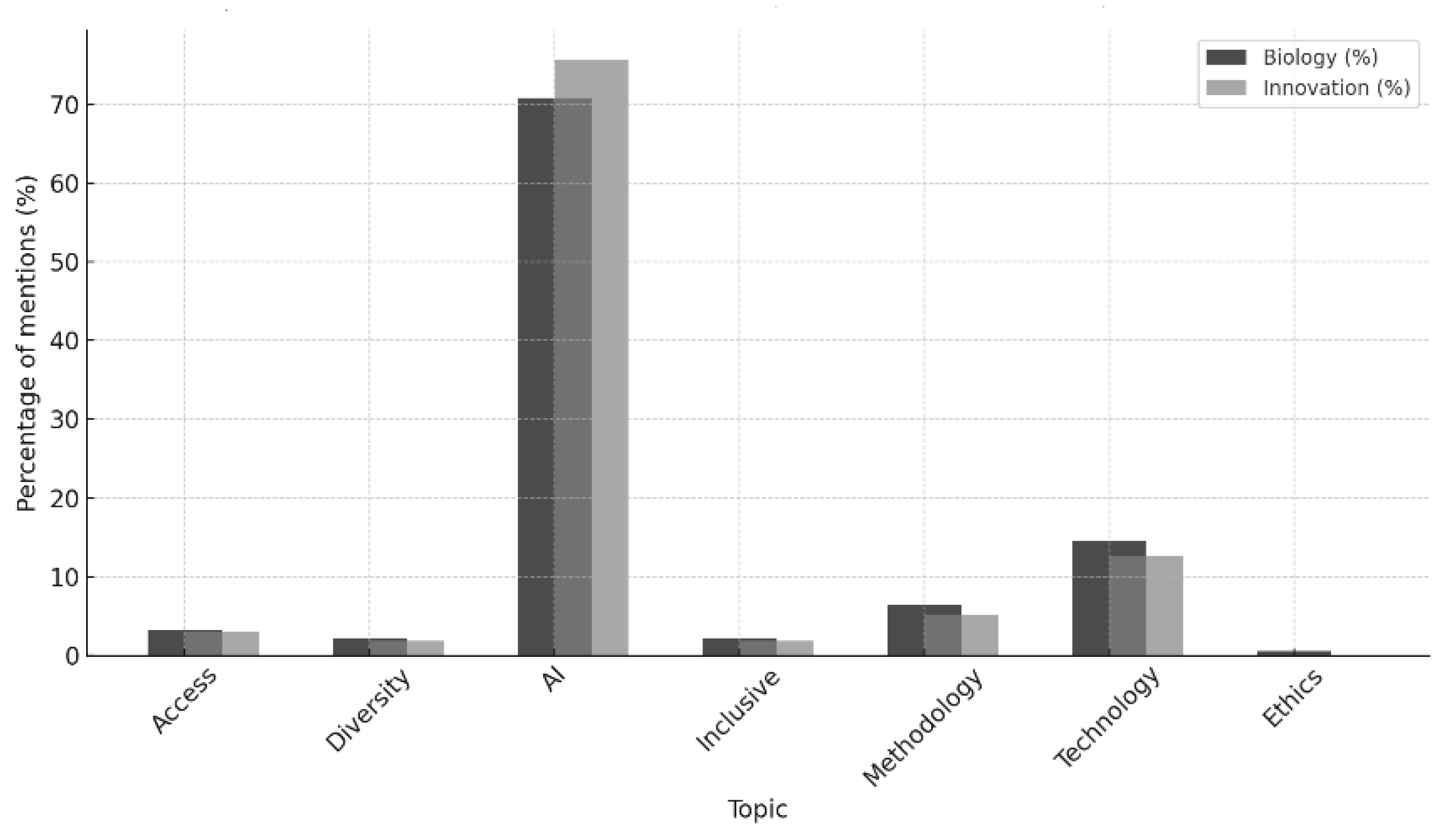

Although this study primarily follows a qualitative research design, it also incorporates descriptive quantitative elements to support interpretation. Specifically, the analysis includes the counting of term frequencies and thematic mentions (see

Table 1 and

Figure 1), which serve to contextualize qualitative findings. However, these descriptive measures are embedded within a qualitative content analysis rather than constituting a distinct quantitative phase. Therefore, the study is not presented as mixed methods but as a qualitative analysis enriched with descriptive statistics. This clarification ensures transparency about the nature of the data and the scope of our analytical approach. These free training programs were announced through a public, open call, in which teachers from various specialties and geographical areas of the country enrolled. The training followed an 8 h workshop format, combining theoretical grounding with hands-on practice. The session began with an introduction to key AI bias concepts, ethical principles, and illustrative real-world cases, followed by interactive group work on prompt design and bias identification. This synchronous component was directly linked to a virtual Moodle forum, where participants extended the discussion asynchronously over the following week. In this forum, they revisited workshop cases, debated ethical dilemmas, and collaboratively refined inclusive prompt strategies. This blended structure ensured a coherent progression from conceptual understanding to applied reflection, establishing continuity between guided learning and autonomous critical dialogue.

This formative intervention is grounded in the recognition, extensively documented in recent research, that algorithmic systems are sociotechnical products deeply influenced by values, power dynamics, and historical contexts [

33,

34]. It is assumed that AI is far from being a strictly technical field; rather, today it serves as a locus for either the reproduction or the questioning of entrenched social, institutional, and cultural inequalities, given that its functioning—and its errors—reflect human decisions codified into data, models, and automated processes [

35].

The methodological design of the corresponding sessions (totaling 8 h) prioritized experiential and collaborative learning in order to foster not only conceptual understanding of algorithms, but also a critical appropriation of their affordances and limitations. The introduction positioned students to confront the omnipresence of AI in their daily lives through familiar examples such as digital recommendation systems (Netflix, Instagram) and social media platforms. This initial approach allowed students to problematize the invisibility of algorithms and their influence on behaviors, tastes, consumption, and perceptions, as highlighted in critical digital literacy studies [

36,

37].

To advance understanding of the technical and sociocultural mechanisms of bias, participants engaged in a practical supervised-learning activity using gamified simulators. This activity made tangible how AI learns through patterns found in received data and demonstrated that classification errors are not only technical flaws but also reflect limitations or partialities in the selection and quantity of training data. As Buolamwini & Gebru [

34] have shown, the consequences of such errors can be severe when they affect the rights, opportunities, or recognition of underrepresented individuals and groups. Subsequent reflection, enriched through collaborative work with digital tools, linked the technical notion of pattern with the ethical and social dimensions of bias, emphasizing its inevitably situated character [

32,

38,

39].

Introducing students to the concept of algorithmic bias and its connection to systemic discrimination required delving into its definition as a systematic error stemming from deficient sampling or from the criteria or classifications chosen in algorithmic design [

35,

40]. The analysis of concrete cases, such as Amazon’s automated hiring system—which was withdrawn for showing a preference for male candidates due to training data predominantly consisting of male résumés—helped illustrate the labor and social implications of algorithmic bias and provided a springboard for discussing the responsibilities of developers and companies in preventing these problems [

41,

42].

The intervention also included a unit on experimentation with generative AI, where participants crafted and analyzed prompts concerning groups frequently subject to stereotyping. This exercise confirmed, in line with recent studies, that generative systems tend to reproduce limited and biased narratives when training data lack diversity, creativity, or cultural sensitivity [

43]. Thus, AI-generated text became an opportunity to discuss authentic creativity versus mere automated repetition, and to analyze how cultural products from AI can perpetuate stigmatizing views if there is not critical intervention in both training sets and use guidelines [

35].

Finally, the collaborative production of an open letter on responsible AI use served as a synthesis and ethical appropriation exercise. The process of formulating recommendations, debating priorities, and recording or sharing these reflections via technology reinforced the sense of active citizenship and awareness of contemporary AI challenges. Thus, the intervention not only provided technical knowledge but, in line with transformative pedagogy, also promoted the development of critical and argumentative capacities, as well as a willingness to participate in public debates about rights, algorithmic justice, and digital equity [

33,

44].

In summary, the proposal integrated both technical and social exploration of AI bias, prioritizing the construction of a complex, ethical, and situated perspective. The aim was not to foster the uncritical mastery of digital tools, but to enable students to identify, analyze, and question the power structures underlying intelligent systems and to propose alternatives oriented toward justice and equity in the design and use of these technologies [

32,

34,

35,

38].

The virtual forum was set up as a space for dialogue and collaboration on the Moodle platform, with the participation of 102 teachers and postgraduate students from different regions and specialties. The participants were organized into two main cohorts according to their academic affiliation: the biology cohort, composed of educators and postgraduate students specializing in biology and related sciences, and the Innovation cohort, which included participants from a multidisciplinary education innovation program. The comparison between these two groups was intended to explore whether disciplinary background influenced how educators perceived algorithmic bias and ethical AI integration. This distinction allows for nuanced interpretation of discourse patterns and thematic emphases across scientific and pedagogical domains. Participants were recruited through an open call circulated across universities and teacher training institutions in the Domini-can Republic. The invitation described the professional development course “Ethical AI in Education” and encouraged voluntary enrollment. Participation was entirely optional, with no academic credit or financial incentive. Before engaging in the activities, all participants received an informed consent form detailing the study’s objectives, confidentiality protocols, and voluntary nature. Only those who signed the consent form were included in the dataset. This process ensured adherence to ethical standards and transparency in participant involvement. Participants represented a broad range of professional experiences from early career lecturers to senior faculty members—with teaching experience spanning between 3 and 25 years. Although most participants were active educators in higher education, their prior familiarity with AI tools was generally limited. Fewer than 20% reported having previously used AI for instructional purposes. This heterogeneity of experience provided an ideal context for observing how dialogic reflection influenced bias awareness and inclusive pedagogical thinking across different professional stages. The sample consisted of higher education institutions (Higher Education), which confines the analysis to this specific sector. Of these, 26 were part of the Biology cohort (25.5%) and 76 were part of the Innovation cohort (74.5%). This distribution allowed for the comparison of discourses and reflections from different disciplinary fields, facilitating the analysis of similarities and contrasts in the way algorithmic biases and their educational implications are perceived. The forum was organized into thematic threads linked to practical cases of algorithmic bias (e.g., Amazon’s automated hiring system, the generation of stereotypical texts by AI, and inequality in technological access). In each thread, participants were asked to comment, debate and respond to their peers’ contributions, generating a process of negotiation of meanings and critical reflection. The contributions were collected and analyzed using Atlas.ti software (version 25), applying a predefined system of categories:

Quality of participation: depth of argument and relevance of examples.

Strategies for identifying biases: resources and methods proposed by teachers.

Ethical responsibility: individual and collective conceptions of the role of teachers in relation to AI.

Social impact: perceived consequences for students, in the dynamic.

Equity proposals: initiatives to redesign prompts or activities with inclusive criteria.

This methodological approach allowed us to examine the forum as a discursive space where participants not only expressed individual viewpoints but also collectively articulated responses for the critical and just integration of AI in teaching. The categories enabled analysis of thematic co-occurrences—such as the link between bias identification and equity-oriented proposals—consistent with dialogic learning [

45] and algorithmic justice frameworks [

22,

46]. These excerpts were then integrated into the higher-order analytical categories described above, linking teachers’ narratives to the theoretical framework of algorithmic justice.

2.1. Methodology and Objectives

The general objective was to analyze how a dialogic and practical training on artificial intelligence enables postgraduate teachers and students to identify, reflect on, and propose strategies to mitigate algorithmic biases in educational contexts, promoting inclusive practices and algorithmic justice. From this central purpose, the following specific objectives were derived:

To explore teachers’ perceptions and experiences regarding biases in artificial intelligence through the analysis of practical cases, collaborative activities, and guided debates.

To evaluate the impact of forum dynamics on the Moodle platform as a space for collective knowledge construction, focusing on dimensions of participation, bias identification, ethical responsibility, social impact, and equity proposals.

To understand, through dialogue among teachers, whether the intervention contributed to strengthening teaching competencies in creating inclusive prompts and designing critical pedagogical strategies that encourage ethical and responsible AI use in the classroom.

2.2. Materials and RELIAmework

To ensure methodological clarity, redundant descriptions of the forum dynamics and analytical procedures have been consolidated here. This subsection now provides a unified account of data collection and analysis, presenting the sequence of activities and coding stages in a concise and coherent manner. The data analyzed come from a virtual forum configured as a dialogic and collaborative interaction space on the Moodle platform, involving 102 postgraduate teachers and students from diverse regions and specializations. The qualitative corpus consisted of three main data sources: (a) discussion threads from the Moodle forum, (b) written responses to open-ended questionnaires, and (c) individual reflective notes shared by participants after the training. Two researchers independently coded overlapping segments of the data to establish intercoder reliability, subsequently discussing discrepancies until full agreement was achieved. Although no formal statistics such as Cohen’s kappa was calculated due to the exploration and qualitative nature of the study, inter-coder reliability was ensured through a negotiated agreement process. Two researchers independently coded a 20% sample of the data, discussed discrepancies, and refined the codebook until full conceptual alignment was reached. The frequency analysis, presented in

Table 1 was used descriptively to identify the most recurrent thematic terms and contextualize qualitative findings rather than to perform statistical inference. In this phase, the TRIC model served as an interpretive lens, guiding how participants’ discussions were examined in relation to technological, relational, interactional, and contextual dimensions of digital ethics. Analytic memos were developed throughout to document insights, emerging hypotheses, and interpretive decisions. Importantly, these memos were not treated as data themselves but served as a methodological aid to enhance transparency and reflexivity in interpretation. All findings reported derive exclusively from participants’ discourse, ensuring that interpretations remain empirically grounded. Beyond segmenting and coding the data, the dialogic analysis examined how meaning was co-constructed through sequences of replies and counter-replies, identifying shifts in stance, negotiation of disagreement, and the emergence of shared ethical positions. Particular attention was paid to how teachers built on each other’s contributions to refine definitions of bias, articulate responsibilities, and formulate equity-oriented proposals—an element that distinguishes dialogic reflection from individual written responses. The organization was based on thematic threads linked to practical cases of algorithmic bias (for example, Amazon’s automated hiring system, AI-generated stereotyped texts, or inequality in technological access). In each thread, participants were required to comment, debate, and respond to peers’ interventions, generating a process of meaning negotiation and critical reflection. The interventions were collected and analyzed using Atlas.ti software, applying a predefined category system:

This methodological approach facilitated an understanding of how the forum functioned as a discursive laboratory, where participants not only expressed opinions but also co-constructed courses of action for the critical and just integration of AI in teaching. Each forum thread was treated as an independent primary document, enabling analysis of participation density, segmentation of significant quotations, and exploration of category cooccurrences (for example, how identifying a bias led to equity proposals). This multilevel approach aligns with dialogic learning [

45] and frameworks of algorithmic justice in education [

22,

46].

To prevent any risk of circular reasoning, analytic memos were explicitly distinguished from the data analyzed. While memos guided interpretation and theoretical linkage, they did not serve as empirical evidence. All conclusions in

Section 3 and

Section 4 are supported directly by the participants’ own contributions—quotes, reflections, and forum interactions—ensuring that the analytical reasoning remains grounded in the observed data rather than in the researchers’ interpretive notes.

3. Results

Section 3 is organized around the study’s three specific objectives:

(a) exploring teachers’ perceptions and experiences regarding AI bias; (b) evaluating the impact of the Moodle forum as a collaborative learning space; and (c) identifying whether the training contributed to strengthening inclusive prompt design and ethical teaching practices. Each subsection presents empirical findings corresponding to one of these focal points, directly linking results to the study’s objectives and facilitating a clearer understanding of how the data address the research aims. Using the visualization features of Atlas.ti, conceptual networks were generated that reveal relationships between categories, codes, and quotes. These networks enabled identification of discursive patterns, causal connections, and areas of tension between declared ethics and professional practice. Some of the most notable relationships identified were:

3.1. Teachers’ Awareness of AI Bias

Awareness of bias positively correlates with the perception of professional responsibility, though this does not always translate into explicit mitigation strategies. The training received emerges as a mediating variable between recognizing the problem and proposing concrete actions. From the analysis, the following key indicators were identified to understand teachers’ responsibility related to AI and biases (

Table 1).

The frequency analysis of thematic mentions in qualitative responses allowed identifying variations in discursive intensity between two participant cohorts (

Table 2). This facilitates the comparison of discussion emphases between the Biology specialty group and the Innovation group, showing not only the number of mentions but their relative weight within each group’s conversation. Overall, the term AI concentrates the majority of references—70.8% of mentions in Biology and 75.6% in Innovation—evidencing that the discussion was strongly centered on the technological tool itself. Nevertheless, relevant differences appear in other subjects:

Methodology, understood as pedagogical integration of AI, was mentioned in 6.5% of Biology and 5.2% of Innovation discussions, suggesting a slightly greater emphasis in the former cohort on linking AI to concrete teaching strategies.

Access, related to technological inequality and students’ material conditions, had 3.2% mentions in Biology and 2.9% in Innovation, reflecting a shared concern that is somewhat more pronounced in the first cohort.

Topics of diversity and inclusion showed similar values between cohorts (≈2%), indicating that while relevant, they occupy a much smaller space in discourse relative to the core theme of AI.

These figures suggest that although AI constitutes the debate’s nucleus, social and pedagogical dimensions are still emergent and less intense than technical considerations. This finding aligns with prior studies [

26,

46], which note that teacher AI literacy remains primarily focused on tool operation, with reflections on bias, equity, and algorithmic justice still peripheral and fragmented.

3.2. Ethical and Inclusive Practices

Before examining the ethical and inclusive practices reflected in teachers’ discourse, it is necessary to contextualize how the main thematic dimensions are distributed across the dataset. The frequency analysis provides an overview of which topics occupy a central position and which appear more marginal, offering an initial indication of the relative weight that technical, ethical, and socio-educational considerations hold within participants’ reflections. This panoramic view serves as the starting point for interpreting how these themes later unfold in discursive practices and shape perceptions of professional responsibility, equity, and the educational use of AI. Against this backdrop,

Figure 1 and

Table 2 illustrate how these thematic trends manifest quantitatively within each cohort. As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 1, technical references to AI dominate the discourse, while ethical and inclusion-related dimensions remain comparatively less salient—an imbalance that becomes clearer in the qualitative excerpts and coded categories presented next.

References to methodology and access are more frequent in Biology, while diversity and ethics are mentioned similarly in both groups. This suggests that despite technology being the focal point, ethical and equity considerations are just beginning to emerge, confirming that teacher AI literacy requires consolidation of ethical and socioeducational dimensions.

The coded citations help identify discursive and thematic patterns present in the primary documents, capturing teacher voices and their perceptions about algorithmic biases, ethical responsibility, and equity concerning AI use in educational contexts. Segmentation of collected texts from open questionnaires extracted significant fragments representing complete, meaningful ideas directly linked to study objectives.

These citations illustrate the diversity of stances observed in the sample—from favorable attitudes toward AI integration to strengthen inclusion, to ethical caution and awareness of structural inequalities that the technology might reproduce. The inductive coding approach preserved teachers’ original language, allowing meanings to emerge from data rather than preconceived conceptual frameworks. Representative citations include:

Citation A (Innovation): “Innovative teaching methodologies allow effective integration of AI to address diversity in the classroom.” This expresses a positive valuation of AI when linked to inclusive education.

Citation B (Biology): “Inclusive education and attention to diversity have always been my focus; AI can help but care must be taken regarding biases.” Here a critical awareness about responsible AI use is perceived.

Citation C (Innovation): “Information technologies are useful, but not all students have access or conditions to benefit equally.” This reflects an ethical concern about equity of access—an indication of structural bias.

Each quote was subsequently inductively coded focusing on emerging meanings and their relation to algorithmic bias, teacher responsibility, and educational equity dimensions.

Table 3 synthesizes the linkage between original quotes and assigned codes, showing how individual narratives become analysis units advancing interpretive categories of higher order.

The linking of quotations to theoretical codes reflects the need to transcend the literal description of teachers’ narratives and situate them within a broader analytical framework grounded in algorithmic justice and critical theories of technology-mediated education. As Bender & Friedman [

47] point out, interpreting algorithmic biases is not limited to identifying technical errors but requires recognizing how data and AI systems reproduce sociocultural inequalities in educational environments. Assigning codes to each quotation preserves the contextual meaning expressed by educators while operationalizing key concepts from the theoretical framework for analytical purposes. Authors such as Morley et al. [

22] and UNESCO [

48] underscore the importance of integrating ethical and social dimensions into AI-in-education research to better understand not only biases but also professional responsibility and the socio-educational implications of AI use. The subsequent grouping into larger categories follows the axial coding procedure [

49], whose purpose is to identify relationships between meanings expressed in the data and the conceptual structures organizing them. For example, the categories “AI Bias” and “Ethical Awareness” enable recognition of the problem and critical reflection, while “Teacher Responsibility” and “Integration Strategies” point to fields of action and potential responses from educators. The “Social Impact” category incorporates consequences for students and educational communities, aligning with frameworks of educational justice and digital equity [

46]. Selected examples (

Table 4) illustrate how these categories emerge in concrete situations—from unfair penalization of responses by normative algorithms to the emotional impact experienced by students labeled as low-performing by automated systems. These narratives confirm international literature warnings that algorithmic biases are not isolated incidents but structural phenomena with ethical, pedagogical, and social repercussions [

50,

51].

3.3. Impact of Dialogic Reflection

To deepen the interpretive rigor of the qualitative analysis, it was necessary to articulate how individual quotations were systematically connected to the theoretical constructs guiding this study. This step ensures that teachers’ narratives are not reduced to descriptive accounts but are analytically positioned within broader frameworks of algorithmic justice and critical AI-in-education research. The following section explains how this linkage was achieved and how it informed the construction of the analytical categories used throughout the study.

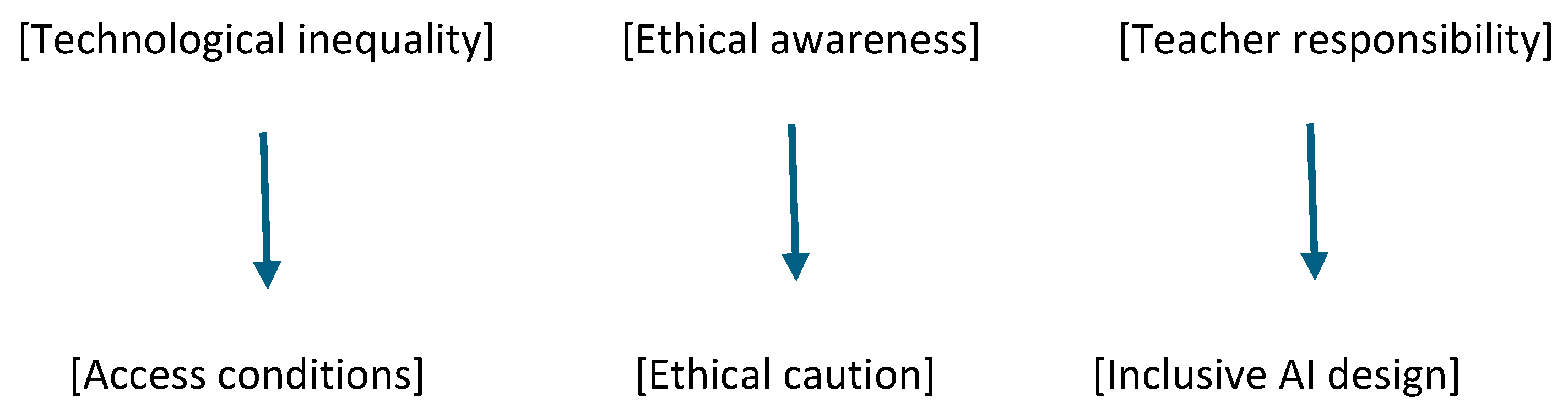

In Atlas.ti, these analytical categories were structured into five code families representing the main dimensions of the phenomenon under study. Each family brought together conceptually related codes derived from the open and axial coding phases: (1) AI Bias, which included “technological inequality” and “structural bias”; (2) Ethical Awareness, grouping “awareness of bias” and “ethical caution”; (3) Teacher Responsibility, encompassing “inclusive education” and “access conditions”; (4) Social Impact, incorporating “academic performance” and “equity effects”; (5) Integration Strategies, which included “inclusive AI integration” and “methodological innovation.” This organization within Atlas.ti facilitated coherence across the coding structure and the visualization of relationships later represented in the conceptual network (

Figure 2, ensuring transparency in how raw data were aggregated into interpretive categories. This analytical step—from quotations to codes and from codes to categories—constructed a bridge between teacher voices and critical theory of AI in education. It enabled the development of a more robust interpretative model that not only describes individual perceptions but also delineates fields of pedagogical action and institutional responsibility, fundamental to advancing a just, inclusive, and ethically supervised educational AI. Representative examples emerging from analysis include:

AI Bias: Automatic correction algorithms penalized responses that did not conform to standard Spanish, affecting migrant students.

Ethical Awareness: AI fails to adequately recognize dialectal expressions, reinforcing exclusion of diverse students.

Teacher Responsibility: Teachers reported a lack of prior training on ethical limitations when using digital tools.

Social Impact: Emotional effects were evident in students labeled as low-performing by algorithms.

Integration Strategies: School leadership proposed adapting grading algorithms to classroom diversity.

During this process, analytic memos—interpretative reflections accompanying coding—were developed to consolidate inferences, observe connections, and detect pedagogical or institutional implications. These memos reveal, among other insights, that algorithmic invisibility functions as a form of silent exclusion, that the lack of teacher training generates a cascade of errors in ethical AI application, and that the most effective improvement proposals tend to originate locally with inclusive approaches. For instance, memo MA-04 “Emerging Critical Awareness in INNOVATION Cohorts” exemplifies teachers’ genuine concern for equity. Although not always employing technical language about algorithmic bias, their ethical intuition formed a solid foundation for future specialized training.

These findings highlight that dialogic reflection enabled teachers to:

Recognize their own limitations and prior biases in using technologies;

Connect student diversity and intersectionality with AI functioning and outputs;

Collaboratively explore strategies for bias mitigation and prompt redesign.

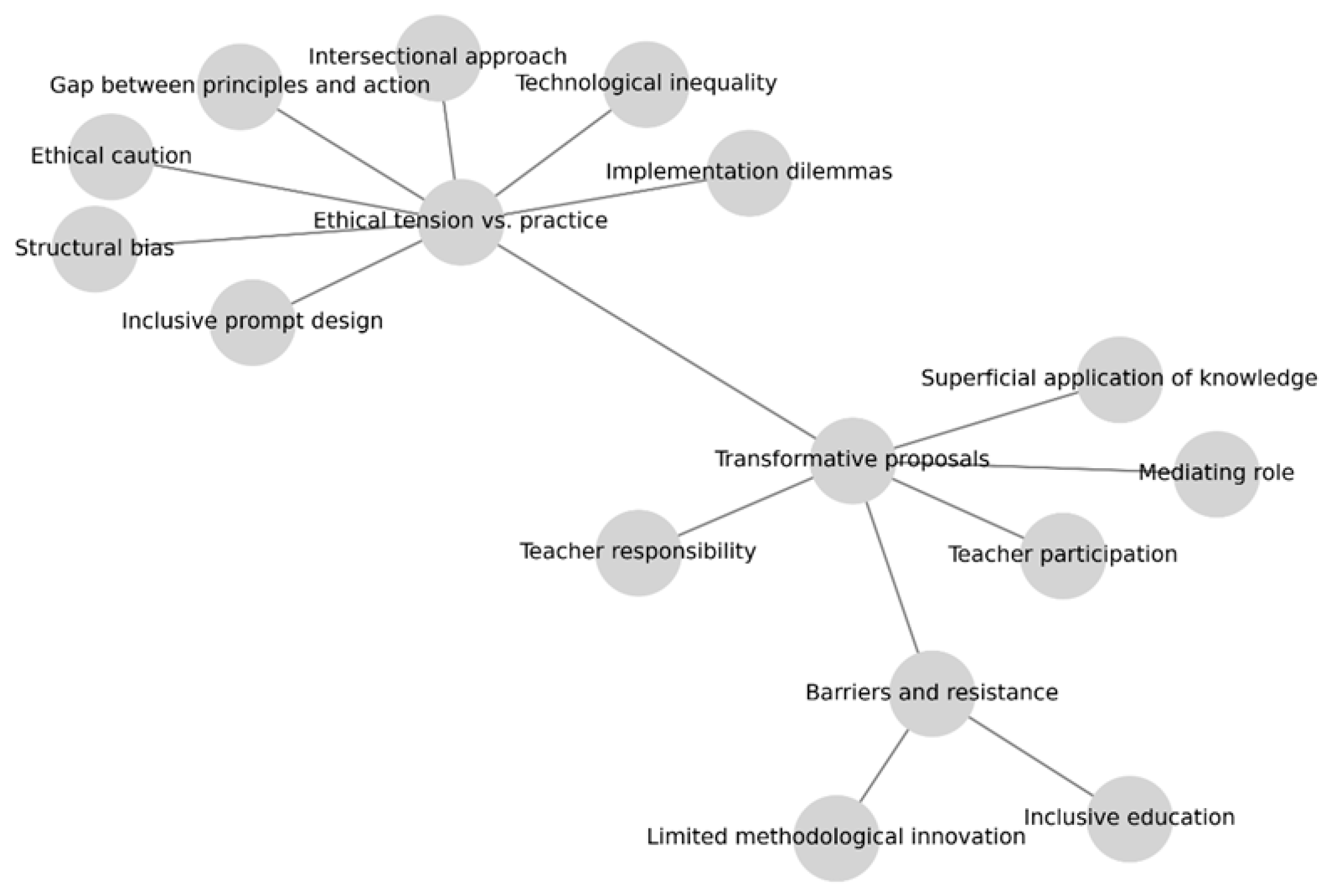

The analysis performed using Atlas.ti also enabled the representation of these relationships in conceptual networks that illustrate the transition from initial observations to ethical reflections and proposed actions. One such network, shown in

Figure 2, graphically synthesizes how the concrete experience of identifying a bias (for example, penalization of nonstandard language) triggered a reflective process among teachers, which led to inclusive action proposals such as redesigning activities or collaboratively reviewing prompts. The training thus functioned as a catalyst for critical awareness and shared responsibility, facilitating a transition from problem recognition toward the construction of ethically grounded solutions.

Overall,

Figure 2 not only represents the connections between categories but also makes visible the journey teachers undertook from identifying a concrete problem to formulating response strategies. This conceptual network evidences that awareness about algorithmic biases can become a catalyst for pedagogical transformation when accompanied by dialogic and collaborative spaces. Thus, the visual analysis reinforces the idea that training in inclusive AI requires both ethical frameworks and concrete practices to guide teaching action.

The conceptual network generated from qualitative analysis using ATLAS.ti graphically represents the relationships among the most significant discourse dimensions concerning algorithmic discrimination. Unlike a linear structure, this network organizes data around five core code families that serve as structuring nuclei of the phenomenon:

Barriers and Resistances: Highlighting obstacles impeding ethical AI implementation in educational contexts, including superficial application of knowledge gained in trainings and scarce methodological innovation integrating AI inclusively.

Ethical Awareness of Bias: Grouping reflections on recognizing technological inequalities [

52] and structural biases in algorithmic systems. Also includes emerging ethical caution among teachers facing automated decisions.

Transformative Proposals: Compiling initiatives aiming to foster a fairer, more inclusive AI—such as ethically oriented prompt design, teacher participation in system adjustments, and intersectional approaches to technological equity analysis.

Teacher Responsibility: Emphasizing the mediating role of teachers between technology and pedagogy, addressing inclusive education, access conditions, and co-responsibility in critical AI integration.

Tension Between Ethical Intentions and Practical Application: Reflecting the gap between declared principles and real actions in using algorithmic technologies, highlighting implementation dilemmas, institutional difficulties, and perceived contradictions between ought-to-be and everyday practice.

The visual representation (

Figure 3) shows the dynamic interrelation among these five dimensions. For example, lack of technical and methodological training (barrier) may limit teachers’ capacity to develop transformative proposals, whereas well-developed ethical awareness can bolster teacher responsibility and lessen the gap between intention and practice. This relational architecture facilitates understanding algorithmic justice not as merely a normative ideal but as a field of disputes, decisions, and mediations constructed from classrooms, policies, and reflective practices. The qualitative analysis revealed a complex network of relationships between ethical concerns, algorithmic design, and educational practices. Using ATLAS.ti, a conceptual network (

Figure 3) was created to visually convey the interdependence among topics such as bias invisibility, ethical responsibility, pedagogical mediation, and inclusive innovation. This network serves as an interpretative lens to comprehend how algorithmic discrimination manifests in educational contexts and how it can be actively counteracted through informed pedagogical actions.

The figure illustrates interconnections identified in teachers’ discourse on algorithmic bias in education. Central dimensions like ethical tension vs. practice and transformative proposals link to related categories including inclusive prompt design, technological inequality, ethical caution, and intersectional approach. Additional nodes represent barriers (e.g., limited methodological innovation, barriers and resistance) and areas of responsibility (teacher participation, inclusive education). This network highlights the dynamic interplay between ethical awareness, professional responsibility, and structural obstacles in AI integration within educational.

4. Discussion

Measuring the relative frequency of the term “AI” in participants’ discourse provided an indirect indicator of thematic salience and focus, helping to contrast the predominance of technical over ethical considerations. This approach aligns with prior discourse-analytic studies that quantify topic prominence to contextualize qualitative interpretation [

22,

26]. The findings provide empirical support for the proposed hypothesis-driven model, indicating that dialogic reflection functions as a mediating mechanism linking bias awareness to inclusive pedagogical practice. The network analysis showed clear pathways from problem identification—in this case, recognizing bias such as penalizing nonstandard language—to concrete proposals, such as redesigning pedagogical activities and collaboratively reviewing prompts (

Figure 2). The findings empirically confirm that dialogic reflection mediates the link between bias awareness and inclusive pedagogical practice. By engaging in collaborative discussions and practical exercises, participants were able not only to critically assess algorithmic systems but also to propose feasible strategies for creating fairer technologies. One of the most innovative outcomes was the ability to design inclusive prompts, a skill directly linked to objective 3, which sought to strengthen teachers’ competences in creating inclusive prompts and pedagogical strategies. This practice empowers educators to mitigate systemic bias by shaping the interaction between human agency and algorithmic outputs, positioning teachers as active contributors to algorithmic justice rather than passive users of technology. In relation to objective 1—exploring teachers’ perceptions and experiences regarding AI bias—the results highlight that participants, even when not employing highly technical vocabulary, demonstrated clear ethical intuitions. This trend resonates with previous evidence from teacher-training contexts [

20,

25], confirming that initial ethical intuitions often precede the development of formal conceptual frameworks on AI bias and justice. These intuitions served as an entry point for dialogic reflection, which progressively expanded into a more structured awareness of risks, responsibilities, and possible mitigation strategies. While the differences between cohorts were explored descriptively, their modest variation suggests that disciplinary background shapes emphasis but does not fundamentally alter the ethical reasoning processes activated during dialogic reflection. Although the Innovation cohort was substantially larger than the Biology group, the analytic strategy mitigated this imbalance by comparing proportional frequencies rather than absolute counts and by examining qualitative patterns within each cohort independently before drawing cross-group interpretations. This ensured that dominant voices did not overshadow minority perspectives and that thematic contrasts reflected genuine discursive differences rather than sample size effects. This process illustrates how initial ethical concerns can be transformed into professional commitments when supported by collective learning environments. This is one of the clear patterns emerging from the network visualizations (

Figure 2) and coded data (

Table 1), the positive correlation between teachers’ awareness of algorithmic bias and their perceived professional responsibility to address these issues. Dialogic interaction also operates as a micro-process of algorithmic justice and intersectionality. By collectively examining how AI systems differently affect students depending on gender, linguistic background, socioeconomic status, or migration experience, participants enacted the core principles of intersectional analysis—linking multiple axes of inequality to algorithmic behavior. This situated, relational examination of harm is what turns dialogic reflection into a practical enactment of algorithmic justice rather than an abstract theoretical stance. Participants explicitly acknowledge algorithmic bias as a systemic but often invisible problem influencing educational equity. They recognize that AI tools can perpetuate exclusionary practices, especially when penalizing nonstandard language or neglecting cultural diversity (see the network analysis). Nevertheless, this ethical awareness does not consistently translate into concrete mitigation strategies. This ethical–practical tension emerges from the coexistence of strong normative commitments and limited operational tools. Participants expressed clear ethical principles, yet lacked institutional guidelines, curricular time, technical training, or decision-making authority to implement them. As a result, teachers often recognized the need for equitable AI practices without possessing the structural or methodological means to enact them—revealing that ethical agency is constrained by organizational and sociotechnical conditions. The tension between declared principles and practical implementation—the “ethical–practical tension” coded in the analysis—indicates a gap between knowledge and applied pedagogical innovation. This gap reflects systemic barriers, including insufficient training and institutional support. The limited presence of explicit bias mitigation actions in teacher discourse shows that although ethical concerns are recognized cognitively, operationalizing this awareness into consistent, context-sensitive practices remains challenging. It should be noted that the sample corresponds exclusively to the field of Higher Education, which limits the generalization of the results to other educational levels.

Addressing objective 2, which examined the impact of the training activity and the Moodle forums as spaces of collective knowledge-building, the analysis revealed that asynchronous dialogues facilitated the articulation of individual concerns and their consolidation into shared ethical stances. Teachers connected issues of diversity, equity, and intersectionality with the functioning of AI systems, demonstrating the capacity of online collaborative spaces to mediate between personal experience and theoretical frameworks. The TRIC model reinforces this connection: its emphasis on Relationships and Context aligns naturally with intersectional perspectives, as both frameworks foreground how social identities, power structures, and communicative dynamics shape the meanings assigned to AI outputs. By integrating TRIC with intersectionality, the analysis captures how algorithmic harms emerge not only from technical design but from relational and contextual conditions embedded in educational environments. The memos generated during the analysis further confirmed that dialogic interaction was key to enabling critical awareness and actionable proposals. The analysis highlights training and capacity-building, identified as key dimensions (

Table 1), as crucial mediators between problem recognition and the generation of equitable AI integration strategies. The indication that teachers who engaged more deeply with dialogic and action-oriented learning spaces were more likely to propose transformative approaches points to the centrality of sustained professional development. Specifically, discussions concerning inclusive prompt design and collaborative system adjustment indicate that methodological innovation is stimulated by experiential, participatory training formats. The training sessions’ experiential design—utilizing gamified simulators and collaborative forums (see

Section 2.1)—seems to have effectively mobilized teachers’ ethical awareness into proposing local adaptations, such as prompt reconfiguration and activity redesign, which align with scholars’ suggestions for co-constructive AI ethics frameworks [

17,

22]. Another key insight concerns the shared responsibility in the development and use of AI. Participants consistently emphasized that accountability should not rest solely with educators: developers must design algorithms with diverse datasets and transparent processes, while governments should enforce regulatory frameworks that prevent discriminatory outcomes. Within this triad, teachers emerge as mediators who can evaluate AI tools critically before integrating them into classrooms, ensuring that their use aligns with ethical and inclusive principles. The discussion also highlighted the broader social and ethical consequences of algorithmic bias. In education, biased systems may disadvantage students from minority or nondominant backgrounds by reinforcing stereotypes or penalizing nonstandard language. In employment, recruitment algorithms risk excluding qualified candidates due to gender or socioeconomic markers, while in justice systems, biases can translate into disproportionate surveillance or sentencing. These reflections illustrate that addressing bias is not only a technical challenge but a societal imperative that intersects with issues of equity and human rights. Linking these findings to the qualitative analysis, five dimensions emerge as crucial interpretative keys. Barriers such as lack of training confirm argument that ethical integration of AI in education often remains superficial without pedagogical support [

1,

20]. Ethical awareness resonates with Floridi and Cowls’ [

26] framework, underlining that ethical literacy is indispensable for fair AI. Transformative proposals, though still fragmented, align with recommendations from INTEF [

16] on equipping teachers with concrete tools for mitigation, while the responsibility attributed to educators reinforces Flecha [

45] view of teachers as cultural mediators. Finally, the tension between ethical intention and practical implementation echoes Mittelstadt’s [

29] claim that principles alone cannot guarantee justice without realistic mechanisms of application. It should be pointed out how coded data and emerging clusters in the conceptual network emphasize teachers’ growing recognition of the importance of sociocultural factors in algorithmic fairness. Although explicit mentions of the term “ethics” were scarce in

Table 2 and

Figure 1, the qualitative data reveal that ethical reasoning was nonetheless embedded throughout participants’ discourse. Rather than using the word explicitly, teachers articulated ethical dimensions through concepts such as fairness, responsibility, and inclusion. This linguistic pattern suggests that ethical awareness was implicit, reflected in the participants’ emphasis on equitable AI use and student diversity. Future training sessions should therefore aim to make ethical terminology more explicit, encouraging educators to name and articulate ethical frameworks directly as part of their reflective practice. Teachers explicitly raise concerns about language penalization, dialect invisibility, and technological access disparities affecting diverse student populations (coded under sociocultural sensitivity and technological inequality). These concerns highlight that ethical AI integration cannot be decoupled from local contexts. The call for intersectional approaches embedded in training and practice reflects broader theoretical frameworks stressing that algorithmic justice entails awareness of multiple, overlapping axes of inequality [

6,

17,

53]. Regarding the discourse analysis, it is worth emphasizing the central prominence of AI in participants’ conversations. As shown in

Table 2, the term AI accounted for more than 70% of thematic mentions, far surpassing other categories such as inclusion, access, or diversity. However, while participants frequently referred to AI as a technical or practical topic, explicit discussions of its ethical implications were comparatively limited. This suggests that teachers often assumed AI as a given part of their professional environment, focusing more on its applications, limitations, and social effects than on articulating the concept of “AI ethics” explicitly. Such a pattern reveals the need to foster not only critical but also explicit ethical literacy, encouraging educators to frame their reflections using clear ethical terminology and conceptual references in future training contexts. Areas for the improvement of this intervention include fostering collaborative spaces where best practices for equitable AI use in classrooms can be shared and iteratively refined. Those spaces should be used for integrating more concrete examples of AI biases—such as real incidents where algorithms perpetuated gender, cultural, or socioeconomic discrimination in student evaluation and admissions—and offering clear, actionable methodologies for inclusive prompt design to facilitate this labor for non-expert teachers. Furthermore, it is essential to develop training spaces that intentionally bridge technical skills with ethical reflection in a deliberate, step-by-step manner. Rather than treating ethical considerations as an abstract addon to technical knowledge, these programs should intertwine both dimensions throughout the training process. One highly effective approach would be to present educators with practical examples showing how language models can be ethically modified and adjusted—using techniques such as finetuning or Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)—and to explicitly teach teachers how to implement such interventions independently. This advanced, hands-on work empowers educators to understand, from the inside, how datasets and prompt design directly influence AI biases. By working on curated datasets and observing the effect of introducing, excluding, or balancing data samples, teachers gain the analytical tools to foresee and compensate for algorithmic partiality. Furthermore, guiding teachers through step-by-step exercises on adjusting prompts and modifying language model behavior fosters not only critical AI literacy, but also a robust capacity for ongoing, sustainable bias mitigation well beyond solely crafting inclusive prompts. Connecting technical mastery with ethical awareness in this way may be too technical and, for sure, exceed the target of the courses we are analyzing. But our analysis has shown that we need to transform ethics from a theoretical checklist into a dynamic and adaptive set of skills and technical competencies that educators can apply as AI technologies evolve. And such tools from GAI like fine-tuning and RAG will allow to do that. Only these comprehensive training programs—grounded in real classroom examples of bias and equipped with practical modules for data intervention, prompt auditing, and iterative model adjustment—would build a unique professional profile that allows teachers to act as informed guardians of fairness, transparency, and inclusion in AI-augmented education. Ultimately, such initiatives do not just mitigate the risk of algorithmic bias—they situate teachers at the heart of responsible educational innovation, capable of leading sustainable, ethically sound digital transformation in schools.

Building upon these empirical insights, the following hypothesis-driven model synthesizes the observed relationships and provides a theoretical foundation for future research. Based on the qualitative findings, we propose a hypothesis-driven conceptual model that encapsulates the relationship between dialogic reflection, bias awareness, and inclusive teaching practices. The model posits that dialogic reflection training (independent variable) fosters teachers’ awareness and critical engagement with AI (mediating variables), which, in turn, lead to more inclusive pedagogical practices (dependent variable). This framework provides a testable hypothesis for future empirical research: that dialogic reflection operates as a mediating mechanism linking dialogic reflection training to measurable improvements in equity-oriented teaching. By articulating this model, we aim to establish a theoretical foundation that bridges qualitative insights and quantitative validation, encouraging further exploration of dialogic reflection as a transformative catalyst for algorithmic justice in education.