A Critical Systematic Review of the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Methodology on University Students’ Autonomy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Documentary Search

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

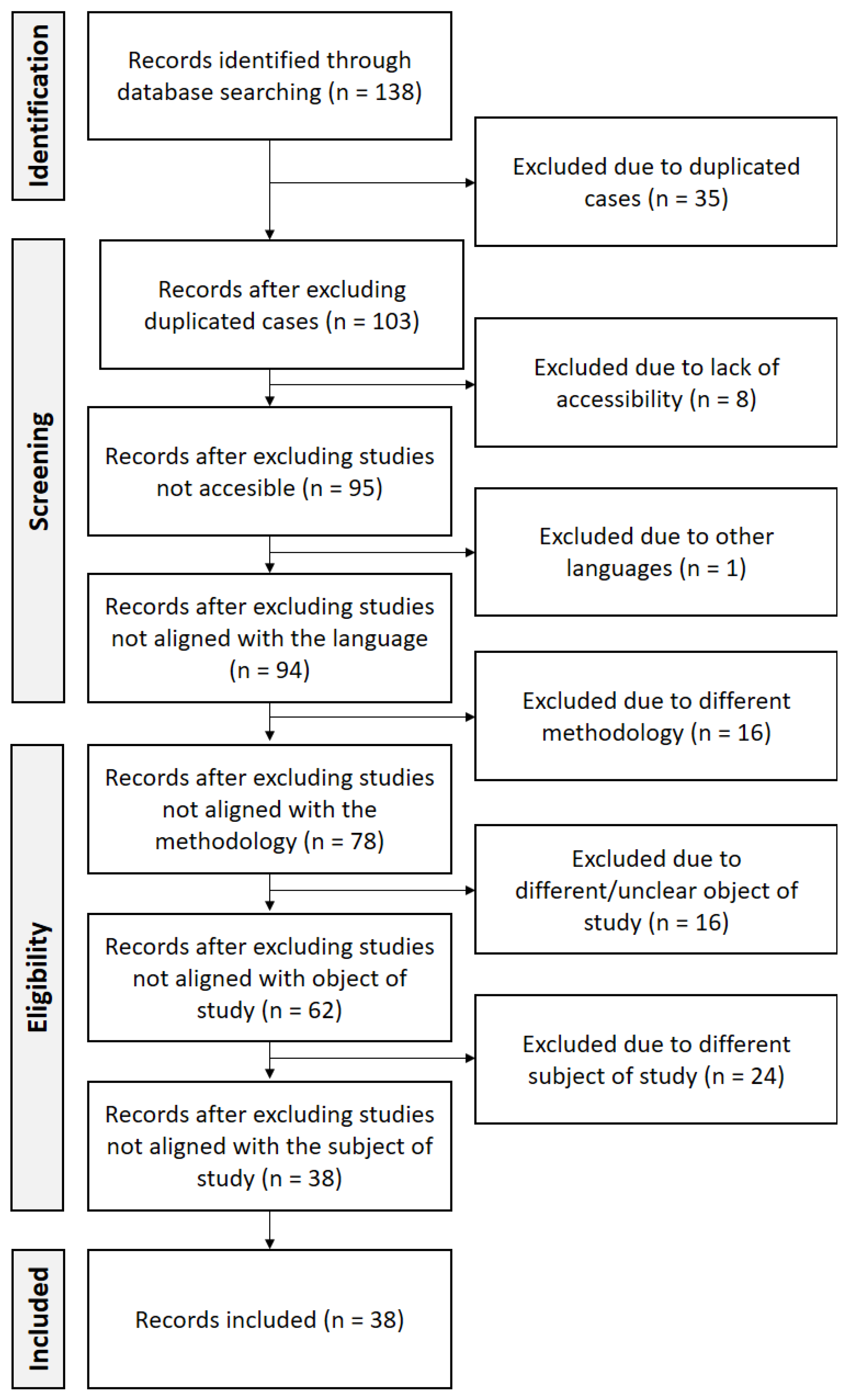

- Accessibility: All studies that were accessible through the selected databases were selected. Studies that were not accessible for the authors were excluded (n = 8).

- Language: Studies in Spanish and English were selected for the analysis. Therefore, studies that were written in other languages were rejected (n = 1).

- Methodology: Both quantitative and qualitative research approaches were accepted. Therefore, studies that just analyzed the research topic theoretically without field work or that proposed an intervention without applying it were rejected (n = 16).

- Object of study: Studies that addressed Flipped Classroom and autonomy were included. Therefore, studies that did not discuss this topic were rejected (n = 16).

- Subjects: Studies that focused on the students’ role in higher education were accepted. Therefore, studies that analyzed the object of study in other role (e.g., in teachers or out of higher education) were excluded (n = 24).

- Time: No time restriction was applied. Any study up to the date of February 2025 was accepted.

- Format: All research formats were accepted, including papers, proceedings, books, and dissertations.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akçayır, G.; Akçayır, M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Domínguez, H. A meta-analysis about flipped classroom methodology in primary education classroom. Edutec 2018, 63, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Dominguez, H. Flipped classroom in the educational system. Trend of effective pedagogical model compared to other methodologies? Educ. Technol. Soc. 2021, 24, 44–60. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27032855 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Jaramillo, N.; Jahren, C.T. A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering Education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, Z.; Akdag-Cimen, B. Flipped classroom in English language teaching: A systematic review. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 33, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, L.; Dawson, P. Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdamli, F.; Asiksoy, G. Flipped classroom approach. World J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 8, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain; David McKay: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gilboy, M.B.; Heinerichs, S.; Pazzaglia, G. Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.A.; Colbert-Getz, J.M. Measuring the impact of the flipped anatomy classroom: The importance of categorizing an assessment by Bloom’s taxonomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2016, 10, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; van Merrienboer, J.J.G.; Paas, F.G.W.C. Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 10, 251–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.C.; Nguyen, F.; Sweller, J. Efficiency in Learning: Evidence-Based Guidelines to Manage Cognitive Load; Pfeiffer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nalipay, M.J.N.; King, R.B.; Cai, Y. Autonomy is equally important across East and West: Testing the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory. J. Adolesc. 2020, 78, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.E.; Deci, E.L. The Effects of Instructors’ Autonomy Support and Students’ Autonomous Motivation on Learning Organic Chemistry: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation Development and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendran, R.; Almeida, S.; Coombes, R.; Hardie, G.; Quintana-Smark, E. The role of self-determination theory in developing curriculum for flipped classroom learning: A Case Study of First-Year Business Undergraduate Course. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2018, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiraal, W.; Nieuwenhuis, G.; Kooij, Y.; Dijkstra, T.; Cloosterman, I. Perceived autonomy support in primary education in the Netherlands: Differences between teachers and their students. World J. Educ. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.M.; Hsieh, P.J.; Uden, L.; Yang, C.H. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing university students’ behavioral engagement in flipped classrooms. Comput. Educ. 2021, 175, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Haruna, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wah, S.K. A systematic review of flipped classroom empirical evidence from different fields: What are the gaps and future trends? Horizon 2019, 27, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsell, E.; Horejsi, M. Science 2.0: A flipped classroom in action. Sci. Teach. 2013, 80, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Çakiroglu, U.; Öztürk, M. Flipped classroom with problem based activities: Exploring selfregulated learning in a programming language course. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2017, 20, 337–349. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.20.1.337 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Sams, A.; Bergmann, J. Flip your students learning. Educ. Leadersh. 2013, 70, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsell, E.; Horejsi, M. Science 2.0: Designing your course like a video game. Sci. Teach. 2013, 80, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbert, R. Inverting the transition-to-Proof classroom. Primus 2015, 25, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Z.D.; Otten, S.; Birisci, S. Mathematics teachers motivations for, conceptions of, and experiences with flipped instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 62, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H. On the relationships between behaviors and achievement in technology-mediated flipped classrooms: A two-phase online behavioral PLS-SEM model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 142, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghufron, M.A.; Ali, G.M.; Nurdianingsih, F.; Fitri, N. Flipped Teaching with Call in EFL Writing Class: How Does It Work and Affect Learner Autonomy? Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, Y. Flipping the Classroom towards Learner Autonomy in an EFL Writing Class. In Teaching and Learning in a Globalized World, Proceedings of the 1st Applied Linguistics and and Language Teaching Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–21 April 2018; Zoghbor, W., Al Alami, S., Alexiou, T., Eds.; Zayed University Press: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, 2018; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Atef, A. Flipped Learning: The Gateway to Learner Autonomy. In Proceedings of the European Distance and E-learning Network Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 9–12 June 2015; pp. 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, E.N.; Wulandari, M. The Implementation of Flipped Classroom in Promoting Students’ Learning Autonomy in a Call Class. Indones. J. Engl. Teach. 2020, 9, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.A.; Nyoman, N.; Made, N.; Hery, M. Promoting Learner Autonomy in Online Argumentative Writing: Virtual Flipped Classroom and Process Writing Approach Enactment. Res Mil. 2022, 12, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Khidr, I.M. An Investigation into the Impact of the Flipped Classroom on Intrinsic Motivation (IM) and Learning Outcomes on an EFL Writing Course at a University in Saudi Arabia Based on Self-determination Theory (SDT). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.Y.; Young, S. A Comparative Study on Blended Learning and Flipped Learning: EFL Students’ Learner Autonomy, Independence, and Attitudes. Korean J. Engl. Lang. Linguist. 2021, 21, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Aprianto, E.; Purwati, O.; Anam, S. Multimedia-Assisted Learning in a Flipped Classroom: A Case Study of Autonomous Learning on EFL University Students. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, W.O. Modelo de Aula Invertida Como Respuesta ante el COVID-19 Para Fomentar la Autonomía, la Motivación y la Expresión Oral en un Curso de Inglés II del BEP de la UdeA. Master’s Thesis, University of Cartagena, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.M. Metodología del Aula Invertida y Aprendizaje Autónomo en Estudiantes de Ingeniería Eléctrica en una Universidad de Lima. Master’s Thesis, University of César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lechuga, C.A. Metodología del Aula Invertida y Aprendizaje Autónomo en los Estudiantes de Administración de una Universidad Privada, Arequipa. Master’s Thesis, University of César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pumacayo, Z.O.; Dionisio, W.; Dionisio, J.Z.; Pumacayo, H.F. Metodología del aula invertida y aprendizaje autónomo en estudiantes de la Facultad de Ciencias–UNE. Rev. Investig. Científica Tecnol. Alpha Centauri 2022, 3, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, M.Y. Aula Invertida y Aprendizaje Autónomo en Estudiantes de Psicología en una Universidad Privada de Arequipa. Master’s Thesis, University of César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Lan, Y. Research and practice of flipped classroom based on mobile applications in local universities from the perspective of self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, S.; Kang, M. Predictive power of grit, professor support for autonomy and learning engagement on perceived achievement within the context of a flipped classroom. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ponce, E.E.; Mora-Pablo, I. Challenges of Using a Blended Learning Approach: A Flipped Classroom in an English Teacher Education Program in Mexico. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2020, 10, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, A. The effect of flipped learning on EFL students’ writing performance, autonomy, and motivation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 3743–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, M. Fostering learning autonomy through the implementation of flipped learning in language teaching media course. Int. J. Indones. Educ. Teach. 2017, 1, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, E.M. La metodología aula invertida en la construcción del aprendizaje autónomo y colaborativo del estudiante actual. Rev. San Gregor. 2019, 31, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H. The Effect of Flipped Learning Using Multimedia on Learners’ Academic Achievement, Intercultural Competence, and Autonomy. Multimed.-Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 22, 84–101. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, A.; Álvarez-Ruf, J.; Vega, E. Implementación de Aprendizaje Invertido y Aprendizaje Basado en Problemas para Abordar las Competencias de Análisis y Autonomía en Estudiantes de Biomecánica y Fisiología Articular; Universidad del Desarrollo: Las Condes, Chile, 2019; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11447/5702 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Polat, E.; Hopcan, S.; Albayrak, E.; Yildiz, H. Examining the effect of feedback type and gender on computing achievements, engagement, flipped learning readiness, and autonomous learning in online flipped classroom. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 1641–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, M.P.; Reyna, G.P. Use of the flipped classroom for the development of autonomy and critical thinking. Hum. Rev. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, H. El Aula Invertida y su Incidencia en el Aprendizaje Autónomo de los Alumnos de Ingeniería Industrial de una Universidad de Lima Norte. Master’s Thesis, University of César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ventosilla, D.N.; Santa Martía, H.R.; Ostos, F.; Flores, A.M. Flipped classroom as a tool for the achievement of autonomous learning in university students. Propósitos Represent. 2021, 9, e1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cay, T.; Karakus, F. The Effect of Flipped Classroom on English Preparatory Students’ Autonomous Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Learning Grammar. Eur. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 2022, 3, e02209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y. Study on Cultivating College Students’ English Autonomous Learning Ability under the Flipped Classroom Model. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2020, 13, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, M.L.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.C.; Pan, S.J.; Guo, J.H.; Tian, Z.E.; Cui, L. The influence of “small private online course + flipped classroom” teaching on physical education students’ learning motivation from the perspective of self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.R. Promotion of learner autonomy within the framework of a flipped EFL instructional model: Perception and perspectives. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 34, 979–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashadi, J. Investigating the Efficacy of Flipped Learning on Autonomy and Skill-Learning of Iranian EFL Learners. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, M.; Hafezi, F.; Asgari, P.; Talebzadeh, M. Comparing the Effectiveness of Flipped and Traditional Teaching Methods in Problem-solving Learning and Self-determination Among University Students. J. Med. Educ. 2020, 19, e110069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, M.; Hafezi, F.; Asgari, P.; Talebzadeh, M. Comparison of the effectiveness of flipped classroom and traditional teaching method on the components of self-determination and class perception among University students. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2021, 9, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaneh, H.; Zoghi, M.; Asadi, N. Effect of the Flipped Classroom Approach and Language Proficiency on Learner Autonomy and Foreign Language Anxiety. Int. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2022, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Campillo-Ferrer, J.M.; Miralles-Martínez, P. Effectiveness of the flipped classroom model on students’ self-reported motivation and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R. Exploring the role of e-learning readiness on student satisfaction and motivation in flipped classroom. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Kumar, K.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, X. The Effectiveness of the Flipped Classroom on Students’ Learning Achievement and Learning Motivation. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2020, 23, 1–15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26915403 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Chih-Yuan, J.; Wu, Y.T.; Lee, W. The effect of the flipped classroom approach to OpenCourseWare instruction on students’ self-regulation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 48, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacaroğlu, O.; Bektaş, O. The effect of the flipped classroom model on gifted students’ self-regulation skills and academic achievement. Think. Skills Creat. 2023, 47, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Domínguez, H. Influence of flipped classroom methodology on the self-concept of primary education students. Aloma 2019, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, B.; Lortie-Forgues, H. An evaluation of the impact of flipped-classroom teaching on mathematics proficiency and self-efficacy in Saudi Arabia. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaser, A.M. Effectiveness of Using Flipped Classroom Strategy in Academic Achievement and Self-Efficacy among Education Students of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2017, 10, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih-Yuan, J.; Lin, H.S. Effects of integrating an interactive response system into flipped classroom instruction on students’ anti-phishing self-efficacy, collective efficacy, and sequential behavioral patterns. Comput. Educ. 2022, 180, 104430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namaziandost, E.; Çakmak, F. An Account of EFL learners’ self-efficacy and gender in the Flipped Classroom Model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 4041–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, M.; Maur, A.; Weiser, C.; Winkel, K. Pre-class video watching fosters achievement and knowledge retention in a flipped classroom. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencastre, J.A.; Morgado, J.C.; Freires, T.; Bento, M. A Systematic Review on the Flipped Classroom Model as a Promoter of Curriculum Innovation. Int. J. Instruct. 2020, 13, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, P.A.; Jackson, D.E.; McLaughlin, P.M.; O’Malley, C.J. Curriculum Design of a Flipped Classroom to Enhance Haematology Learning. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2016, 25, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behforouz, B.; Al Ghaithi, A. The Impact of Traditional and Holistic Flipped Classrooms on Undergraduate Students’ Academic Writing and Autonomy. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2025, 12, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bich, N. Enhancing student engagement and autonomy in flipped classrooms: From a self-determination theory perspective. Tạp Chí Khoa Học Và Công Nghệ 2024, 22, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravani, M.; Khoshsima, H.; Mohamadian, A. On the Effect of Flipped Classroom on Learners’ Achievement, Autonomy, Motivation and WTC: Investigating Learning and Learner Variables. J. Engl. Lang. 2020, 12, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Nilubol, K. The Feasibility of an Innovative Gamified Flipped Classroom Application for University Students in EFL Context: An Account of Autonomous Learning. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2023, 16, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwichow, M.; Hellmann, K.A.; Milkelskis-Seifert, S. Pre-service Teachers’ Perception of Competence, Social Relatedness, and Autonomy in a Flipped Classroom: Effects on Learning to Notice Student Preconceptions. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2022, 33, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galindo-Domínguez, H.; Bezanilla, M.-J. A Critical Systematic Review of the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Methodology on University Students’ Autonomy. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020022

Galindo-Domínguez H, Bezanilla M-J. A Critical Systematic Review of the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Methodology on University Students’ Autonomy. Trends in Higher Education. 2025; 4(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalindo-Domínguez, Héctor, and Maria-José Bezanilla. 2025. "A Critical Systematic Review of the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Methodology on University Students’ Autonomy" Trends in Higher Education 4, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020022

APA StyleGalindo-Domínguez, H., & Bezanilla, M.-J. (2025). A Critical Systematic Review of the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Methodology on University Students’ Autonomy. Trends in Higher Education, 4(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020022