Abstract

This paper explores the impact of technology and wellness in the context of students entering post-secondary education. It aims to provide insights into the use of technology and how it affects students’ wellness. The transition from high school into post-secondary education has often been a complex phase in students’ lives, and such complexity may be especially significant for virtual high school graduates, in other words, students who finished their high school education mostly virtually due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students starting post-secondary education are usually between 17–19 years old, an age period at which these students are more developmentally vulnerable to the effects of rapid physiological, financial, and social changes. Despite some positive aspects of technology usage in education, challenges remain. Students navigate potential academic losses due to ineffective virtual schooling experiences during school lockdowns. This may aggravate students’ adaptation to higher-education culture and norms and academic expectations, especially formal writing standards often required in university papers. Other challenges may include the over-reliance on technology for academic, social, and personal tasks, accentuating students’ difficulties with wellness and requiring a rethinking of learning practices to eloquently respond to students’ needs in the context of the legacy of the coronavirus pandemic. This paper seeks to contribute to the conversation on how post-secondary institutions respond to the need to balance technology and wellness in the context of education. Ultimately, this paper explores perspectives on potential higher institutions’ responses to the impact of technology on students’ mental health and learning as well as implementing wellness practices while integrating technology into education.

1. Introduction

Pursuing higher education is often part of many young adults’ life goals as they transition into adulthood. Worldwide, higher institutions seek to provide students with various opportunities to integrate wellness into academia through numerous social clubs, services, and extracurricular activities and offer complex recreational facilities, including wellness rooms. In addition, students’ individual learning needs are usually accommodated so they can perform their best within the school environment. However, the day-to-day life of students is made of many ‘stressors’ that are complex and sometimes isolating, affecting students’ academic performances and mental health. This paper reflects on technology and wellness to provide some insights into the lives of students struggling to navigate the challenges associated with this process. Seeking to address the impact of technology on students’ wellness and learning, some high schools have banned students’ cell phone use in classrooms, but as these students transition into post-secondary education, how are these institutions responding to the need to balance the use of technology and wellness to provide students with a healthy learning environment? Ultimately, this paper explores perspectives on how higher institutions respond to the impact of technology on students’ mental health and learning as well as the implementation of wellness practices in the use of technology in education, especially in the context of academic writing.

2. Literature Review

There is a plurality of definitions for ‘wellness’, and one of them is inspired by Hettler [1]: “Wellness is functioning optimally within your current environment” [1] (p. 1). Hettler’s [1] wellness model, known as ‘The Six Dimensions of Wellness’, is represented in the Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

Six Dimensions of Wellness Model [1].

Hettler’s [1] ‘Six Dimensions of Wellness Model’ includes six aspects of life that must be optimal for an individual to function the best within the environment to which we choose to belong. As technology becomes more intertwined in our daily lives, it has impacted the current parameters of ‘wellness’, especially among first-year university students. Asselin et al. [2] argue that “the quality of time spent online may be a better predictor of digital well-being than time spent online alone” [2] (p. 1). This may suggest that how we choose to use technology is important in defining the quality of our experiences and influencing wellness perceptions.

Concerns with evolving technology, especially artificial intelligence (AI), and its impact on the lives and well-being of youth have span decades [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, in the last five years, such concerns have become more prevalent as we process the legacy of a pivotal moment in recent history, the COVID-19 pandemic, when reliance on technology became central to communication, social interactions, and education [6]. During the height of the pandemic, technology played a pivotal role in providing opportunities for social interactions. However, the initial excitement over the use of technology, especially among high schoolers, did not bridge the loneliness of being physically present to experience many developmental and social interactions with peers, creating a vacuum in many aspects of their lives, leading to social isolation, education losses, and mental health issues. The legacy of this period is still unfolding as challenges emerge. Many of these students, who finished partially or their entire high school online, are now in their first or second year of university.

Duffy et al. [11] and Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6] point to the difficult process of transitioning from adolescence into adulthood, when developmental changes often have a key impact on young adults’ lives, frequently seen in mental health struggles. Such a process is clearly illustrated in students in their first year of university. These students may struggle to balance their personal lives and studies, making life-changing decisions while handling part-time jobs and private life and navigating their self-image and others and their own perception of ‘success’, especially defined in social media.

According to Duffy et al. [11], this period coincides with a physical, psychological, and social development phase where students adapt to leaving home, making new friends and relationships and entering the workforce, as well as making sense of who they are becoming as their body and mind change, with risks and responsibilities becoming more prevalent in adulthood. University life also comes with its own stressors, as these students may not be prepared to write in the style and level required in academia, impacting their grades and mental health [6,12,13]. McCarthy [12] refers to students entering the university as ‘a stranger in strange lands’, pointing to students struggling to understand what they must do to receive higher grades while adapting to an unfamiliar educational environment. In addition, students must manage their personal lives and the dedicated time often required to do well in academia, with increased responsibility roles. Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6] describes these long-standing complex challenges as a ‘ceremony of passage’ for young adults entering post-secondary institutions. Ultimately, such challenges may lead to coping mechanisms sometimes found in the use of recreational drugs, alcohol consumption, and, in recent years, technology over-reliance and sometimes technology addiction [6,11,14].

Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6] further explains that the ‘ceremony of passage’ became increasingly more problematic during and now after the COVID-19 crisis, as its legacy may continue to significantly impact students’ lives: academically, socially, developmentally, and economically. These factors may have contributed to mental health care distress and the need for more effective mental health support on campus. Anxiety, mood changes, and illicit substance use are common problems experienced among youth aged 18–22 [11,15]. In response to an increasing demand for mental health services in higher institutions and even at the high school level, measures to address such problems go from services to regulations in the use of technology. Studies on the impact of technology on students’ wellness continue to expand, but some researchers point to some benefits and challenges [16].

The relationship between technology and wellness is often confined to the terms ‘technophilia and technophobia’, meaning liking or fearing technology [16,17]. However, High et al. [16] point to ‘the experience’ as an important factor in determining the relationship between technology and wellness:

Different types of well-being comprise different factors and are likely predicted by distinct antecedents. There are many variables in a person’s life, including aspects of their relationships that are intertwined with technology, that are likely to influence their overall sense of well-being.[16] (p. 1058)

The intrinsic relationship among technology, education, and wellness has resulted in a plurality of perspectives.

3. Wellness Perspective

According to High et al. [16], “Relationships have always been an integral part of people’s well-being” [16] (p. 1055). They explain that technology has evolved to play an important role in connecting people and facilitating the development of such processes, often beyond space and time limitations. Even though there must be recognition of technology having limitations and not properly replacing in-person social interactions, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, technology facilitated students’ learning and brought people together when they could not be in the same space. It provided an opportunity for ‘online’ social interactions: creating a virtual space for conversations, sharing a meal, singing together, and often exercising. It also contributed to the popularization of wellness-oriented technology, a new market focusing on online fitness companies, such as Peloton or simply free online yoga classes on YouTube. However, despite the benefits of virtual wellness technologies in supporting adult physical activities, research suggests that in-person wellness practices are often perceived as more effective or preferred [18,19].

Different approaches to technology in the context of wellness have emerged. To illustrate such approaches, digital well-being focuses on improving students’ relationships with technology by regulating its usage, aiming for effectiveness and promoting wellness practices [20]. It seeks to balance physical and mental health practices and productivity in the context of technology. This approach highlights the importance of students’ experiences with technology and its relationship with wellness.

Recognizing the role of students’ experiences is a path to addressing the challenges technology poses to wellness, as technological devices, such as cell phones, have been negatively associated with mental health issues and are often deemed a key stressor in education [21]. To exemplify this point, the use of ChatGPT 4, the most popular among artificial intelligence (AI) text generators, has been a stressor for many students and educators, as it mimics human conversational writing and can be used for plagiarizing papers [6,22]. Another example is students’ excessive attachment to cell phones, which distracts them from learning tasks and leads to phobias, such as Nomophobia—the “fear of being cut off from mobile phone connectivity” [3] (p. 1).

Many students experiencing difficulties adapting their writing skills to university standards may resort to misusing AI technology to fulfil paper assignments [6]. For instance, Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6] suggests that students’ use of AI text generators could be one of the coping mechanisms to bridge their writing deficiencies. However, the idea that ChatGPT is the ‘solution’ quite often does not translate into desired grades. According to Dobrin [22] and Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6], AI tools, such as ChatGPT, are unreliable for writing papers, mainly due to the lack of critical thinking abilities, a mechanical tone, and the failure to use reliable sources. In addition, cheating on written assignments has led to concerns about the implications on learning, ethics, student conduct, and the development of writing abilities necessary to portray critical analytical skills. These concerns have been central to many narratives among educators, and some are terrified of not knowing how to identify and mark an AI-generated paper, with others pondering how to integrate it into their pedagogy and others simply entertaining the idea of educating their students to use it as a tool to improve their writing. Many concerns about students missing the opportunity to develop critical analytical skills due to over-reliance on technology are valid and require policies and regulations to establish clear parameters for students’ adequate usage of AI in their studies.

Other technology-related stressors students experience as they transition into higher education include a sense of personal and professional uncertainty, which often leads to mental health issues [11,23]. Bankins et al. [23] highlight the important role of AI in “many aspects of life and is an increasingly important feature of organizations” [23] (p. 1). Many uncertainties remain as AI technology advances and impacts competitiveness, possibly reshaping career opportunities for young people. Bankins et al. [23] point to students’ concerns over the impact of technology on career choices. This may contribute to other problems related to economic anxiety as students may rethink careers and the potential cost benefit of their degree. However, the authors argue that AI could also help students, to a certain extent, to decide on career paths, as it could assist career counsellors in identifying important competencies, such as reflective, communicative, and behavioural abilities.

Despite these challenges, technology has become a part of our daily lives, and learning how to better utilize and integrate wellness into education is a process that will require time and a continuous understanding of its impact on different aspects of life. Further research is also necessary. Meanwhile, finding ways to manage technology engagement in the context of education may require oversights to curb the unnecessary stress of ‘uncertainty surrounding the use of technology’, which is especially relevant in the early stages of adulthood. This may be addressed through the following:

- Clear policies and regulations in educational environments seeking to develop healthy relationships between education and technology should be implemented [6,21,22]. In other words, the use of technology in classrooms should not be prohibited, but rather, a better craftsmanship sense of purpose should be added, while encouraging a reflective pedagogy approach on how and when to use technology in the context of education, considering the cost benefit for student wellness.

- Teaching should have wellness in mind, while utilizing technology for tasks such as reading, sharing resources, and virtual learning sites [3]. This also allows for a humanizing approach to technology by integrating technology as a learning tool while prioritizing the in-person opportunities required to develop social collaboration skills through engaging class discussions, group work, and combined lecture–seminar lessons.

In K–12 schools in Alberta, physical education is compulsory and there is an increasing focus on mental health problems impacting learning [21]. However, mental health support is not always effective in meeting students’ needs. That is to say, the students’ increasing population and their complex needs are not always met due to limited resource availability. Some schools utilize simpler preventive wellness measures, such as cost-effective initiatives, often based on volunteerism. For instance, some schools provide volunteer-based book clubs and drop-in opportunities for students to play board games or sports during recess. Such initiatives aim to encourage the development of social skills and physical activity habits, seeking to improve students’ mental health in schools.

Similarly, higher education has also invested in students’ wellness, as universities offer a variety of resources to support and engage students in wellness activities [24]. However, research suggests that more needs to be done to address technology addiction and other uncertainties in education [16,22]. A survey indicates that 60 percent of students do not utilize student support services, while some suggest that such services need improvement [25,26]. Revising the curriculum and current wellness services to incorporate practices seeking to identify and mitigate stressors may contribute to positive outcomes. Current stressor areas may include the following:

- Balancing academics and technology—wellness concepts should be integrated into foundational courses. The benefits and risks of using technology in papers should be acknowledged [22], while providing students with opportunities to develop foundational writing skills needed to meet the expectations of academic papers [13].

- Time management awareness—time management skills should be acknowledged to address students’ common need to develop organizational skills to effectively manage different course requirements and include allocated time to wellness activities. This may lead to a more proactive relationship with technology, possibly improving mental health on campus [16].

In conclusion, the process of integrating technology into wellness practices in education is a complex topic which requires further research. However, one may note that technology has become an integral part of students’ lives. It may suggest the important role of higher institutions in helping these students navigate technology effectively by promoting ways in which technology can be utilized in learning and wellness on campus.

4. Education Perspective

Technology is primarily understood as a tool for learning in education. However, its potential for misuse and its impact on students’ learning engagement have led to restrictive regulations on cell phone use in schools in some provinces in Canada [21]. The restriction on device usage, such as cell phones in classrooms, exemplifies the complexity of incorporating technology in education.

Many different technologies can be used for educational purposes. To illustrate this point, video conferencing platforms, which allow for synchronous or asynchronous virtual communications, such as ZOOM and Google Meet, have assisted classes, group work meetings, presentations, and other forms of virtual learning. According to Sandhu et al. [27], video conference platforms have become increasingly popular, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, when they were key to keeping students learning during campus closures. Despite the many positive aspects of these platforms, the authors argue that security and privacy issues concern some users.

Research suggests that the overuse of technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted students’ learning and mental health [6,14]. The detrimental legacy of the pandemic on literacy led to the worsening of students’ literacy skills, especially reading and writing skills [6]. Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [6] argues this may have contributed to the popularization of AI technologies such as ChatGPT, an AI tool that mimics human communications and can produce text.

Writing has become an important means of communication, impacting many aspects of life. Most available technologies favour a digitally written communication format, accentuating its key role in educational and professional settings. We use technology to write emails and to apply for educational programs, scholarships, and jobs, to name a few of the many functions writing has in formal settings. In an educational setting, digital writing, meaning writing facilitated by technology, has become part of academics. We write, submit, and are often assessed through digital writing technologies. Digital writing has some positive aspects, such as saving paper and time and often being able to submit a paper online. However, it also has many challenges since, as technology advances, it presents potential risks to the integrity of the writing process. For instance, AI tools, such as Grammarly’s constant pop-ups, may help with spelling, but they can also affect students’ focus. Another popular AI tool for writing is ChatGPT, and while it can be used to search sources and save time, it can also be detrimental to learning and can contribute to plagiarism.

5. Technology and Writing

Technological advances have further highlighted the importance of writing in communication, transcending its focus on informal settings, such as social media posts. Wilson [28] compares the relevance of formal writing to a life skill due to its impact on people’s lives and well-being. It implies that formal writing is an essential means of communication used for different purposes as students enter adulthood.

The disconnect between the writing skills needed and the ones acquired as students finish high school to navigate formal settings may precede the technology age where cell phones have become an added distraction to learning [6,12,13]. Wilder and Yagelski [13] suggest that such disconnection is a complex problem as implied by curriculum changes, and it could also infringe on teachers’ authority to decide what students need to know, often leading to the writing focus in high school being linked to personal essays, which usually do not follow any rigorous evidence-based and structural features required in formal writing styles, such as academic writing.

As the use of written language becomes more prevalent in formal settings, there is a growing concern regarding teachers’ literacy skills and their impact on teaching outcomes. As Amo Sánchez-Fortún et al. [29] explain, “academic literacy is conceived as a specific formative process in which the teacher acts not as a mere supervisor of grammatical incorrectness or facilitator of creative writing proposals”, suggesting that students need to learn different types of writing styles to communicate effectively and address different audiences [29] (p. 2). These struggles may be rooted in teacher hiring practices and training. For instance, in Alberta, Fontenelle-Tereshchuk [30] argues that there is “a generalization of teachers’ education and abilities that will be moulded into the schools’ contexts”, meaning that teachers are assigned disciplines to teach which they may be not trained for [30] (p. 274). In other words, a math teacher could be assigned to teach English Language Arts, possibly undermining the importance of the training and development of the skillset necessary to teach the subject adequately. One would suppose that investing in developments in formal writing abilities could potentially contribute to bridging the writing skill gap between high school and post-secondary education, improving students’ overall well-being, as this could lead to less reliance on technology for writing.

Regardless of the challenges of using technology in writing, integrating technologies in education is possible. Highlighting the impact of advances in technologies and their usage, for example, AI technologies, specifically Large Language Model (LLM), have emerged as a tool for learning and can potentially be utilized in different learning tasks, especially in formal writing [31,32]. This includes assisting students in formatting citations and enhancing writing skills as an editing tool. AI tools can also be important in further assisting students with learning disabilities [31]. For instance, AI read-aloud tools can support students in learning concepts and tasks such as reading.

A study conducted on 47 students, attending three undergraduate classes of the same advanced-level writing course taught by the same instructor during one semester, illustrated the functionality of well-designed technology-integrating pedagogical practices [32]. The students in this study used ChatGPT as a search engine and editing tool and, sometimes, a starting point for their paper, and these students understood the foundational requirements of academic papers and were responsible for writing a paper and for the quality of its composition. The study shows the potential impact of this type of technology in improving the quality of papers, and could also suggest the following:

- Technology should be incorporated as a tool for learning strategies into curriculum design courses in teacher preparation curricula and professional development initiatives.

In rethinking teacher preparation programs and awareness of the increasing role of formal written styles, Amo Sánchez-Fortún et al. [29] point to the importance of including the following:

- Teacher preparation programs—academic and professional writing literacy courses and improving curriculum designing opportunities to reflect purposely designed practices utilizing technology as a tool.

- Professional development—implementing professional development initiatives to mitigate any possible knowledge gap in practicing teachers’ formal writing style abilities.

Notably, not all high school student graduates seek academic careers. Many students opt for vocational professions as they usually offer competitive salaries, job opportunities, and immediate employment [33]. However, as migration continues to shape society and education, Fuller [33] explains that language is also an important means of integration, especially in Canada due to its diverse population. Regardless of students’ career choices, writing has become the key to success in many aspects of life. Communications have increasingly migrated to online format, and while AI may be an option, it is often not autonomous and will require some degree of oversite to communicate adequately in formal environments, such as universities as well as other professional settings. Regulating technology usage in schools may offer an opportunity to reflect on technology’s role in education in purposely supporting learning goals. However, other measures must be implemented to address the impact that the overuse of technology likely has on students’ well-being and its impact on their communication skills, often seen through writing.

In conclusion, the challenges faced with the use of technology in educational contexts may persist, but hopes are that if purposely applied in learning settings, it could effectively function as a learning tool to support students’ growth [32]. However, technological integration in learning means adding a tool to enhance students’ literacy abilities, and it does not replace the crucial role of teachers in helping students develop the skills necessary to navigate written communication for different purposes. Addressing this complex problem could impact students’ well-being, as it may change how students understand different writing styles and their over-reliance on technology to communicate in formal settings, possibly leading to healthier relationships with technology.

6. Technological Perspective

In recent decades, technology has become an important tool for learning. LLM and AI are examples of technologies easily found in educational settings. Students’ learning experiences with these technologies vary, as most institutions and educators may still be defining policies regarding usage, ethics, and best pedagogic practices, as well as their integration into the curriculum [16]. As previously stated, we may know a lot more about how to utilize video conference platforms than AI technology due to its complex challenges. For instance, the use of ChatGPT as a learning tool may still be in its explorative phase in the search for best practices and approaches to integrate it into the curriculum while mitigating its risks. However, some studies suggest that focusing on students’ effective learning experiences and technology literacy may guide further practices and policies to regulate and utilize AI technology for education purposes [16,32,34,35]. Interestingly, Rapanta et al. [36] highlight the importance of rethinking practices and perhaps the curriculum as “the overall picture now reveals an openness towards innovation and new learning opportunities that were not as evident before” [36] (p. 716).

As High et al. [16] suggest, the experiences students have with technology often define its impact on their wellness. Choi [34] argues that “emerging digital media and web-based networking environments allow people to adopt new perspectives toward the self, the other, their community, and the world at large”, and especially for young people, online and offline defining lines are often intertwined [34] (p. 566). A humanized approach to technology focused on providing students with positive experiences is a necessary step to the healthy integration of its inevitable place in educational environments. Students’ understanding of the positive and negative aspects of technology requires a shift in the technology-centred narrative focus. This may mean that instead of focusing on technology usage, reflect on ‘when’ and ‘how’ technology contributes to our wellness. To educate students on the effective applicability of technology, curriculum considerations are essential to creating a space where the students’ experiences with technology are constructive.

Regardless of the challenge of technology potentially becoming a distraction from other important aspects of life, creating spaces to offer opportunities for students to experience using AI technology as tools in a responsible and goal-oriented environment is key to utilizing the benefits of technology [16]. Such spaces provide options beyond the dichotomy of a technofolia or technophobia overthinking paradigm and rather embrace personal experiences. Some research suggests, for example, that longhand note-taking may be more effective in learning concepts and remembering teaching points—some students may use a computer during this process, and others may prefer paper [35]. However, Voyer et al. [35] explain that for students using digital devices, other factors, such as how well a student can manage potential digital distractions during the notetaking process, can influence the effectiveness of their overall academic learning performance. They note that depending on how students use the two options, this may impact their desired outcomes. In other words, they suggest that if well utilized, digital note-taking practices may be just as efficient in facilitating the retention of information as hand note-taking.

Another key point to address is the ongoing conceptualization of technology education as a human learning activity within an online space, which may be similar, in some respects, to learning initiatives one may have in person. The difference between these two spaces, virtual and in-person, is the perception of such spaces and the time management focus to accomplish a task. However, one may note that some problems linked to internet usage, such as plagiarising papers, existed before the popularization of the internet, but the boundless anonymity aspect of the internet and advances in AI programs that could be used in education made geographical dimensions and its reach more detrimental to the human experience, as we may not be fully prepared to utilize it as a tool effectively. In short, education is struggling to prepare students to understand and utilize technological tools in a meaningful way, not as a replacement for traditional practices but rather as a complement to finishing tasks.

Technology education may be defined as the integration of ethics, the ‘self’ experience, and social responsibility towards the community into the curriculum and teaching practices, while teaching students how to apply technological tools to optimize their learning and wellness. This may be a novelty term, but it is closely connected to the definition of digital citizenship as established norms to regulate technology usage properly and responsibly [34,37]. Choi [34] suggests that the most common conceptualization of digital citizenship concerns how to educate students on how to use technology. He sides with a multilayered approach to digital citizenship where students should be taught to take responsibility but more in terms of being a productive member of a shared, project-based online community, avoiding activities that might negatively impact both traditional and online communities (such as piracy). … also help teachers understand that being informed citizens is not to put something in a search bar and/or just go to the Wikipedia to find information. Rather, teachers can provide more advanced and higher levels of skills and knowledge regarding how to express ideas and opinions online, evaluate information, and create online content [34] (p. 589).

Asselin et al. [2] highlight that 73% of Canadians aged 15–24 spend 20 hours a week playing video games. In general, they add that 9 in 10 Canadians—the highest rate of 26% was among the young ones, aged 15–24—watched online content, such as movies, series, eSports, video game streaming services, YouTube, and TikTok. Despite that there has been no consensus on defining digital addiction [38], the overuse of technology to the point that it interferes with our quality of life and affects one’s focus on different daily task performances and relationships at personal and professional levels may indicate that technology has become a problem and perhaps an addiction.

Voyer et al. [35] suggest that technology can distract students during classes often affecting academic outcomes. While in K–12 classrooms, clear regulations limiting the use of digital devices in schools is a common practice, in higher education, recommendations regulating the use of digital devices in class are still vague. It is usually the instructor who must ‘compete’ with devices, especially cell phones, for students’ attention during class. Banning technology may not be a solution; however, some serious considerations are necessary to address the students’ inability to self-regulate their use of digital devices, as the lack of focus or constant digital distractions can affect students academically, professionally, and personally, which may lead to mental health issues.

To address the increasing challenges of technology, especially AI usage in classrooms, exploring perspectives on technology education may provide some parameters to guide policies and practices, mitigating obstacles. This may include:

- AI-use conceptualization in the curriculum—some elements of AI education and acceptable parameters common to all courses should be integrated, focusing on educating students on the use of AI as a tool, not a replacement for other important academic-analytical and subject-foundational learning practices [32].

- The term ‘digital wellness’ may be relatively new but is of fundamental importance as campuses deal with increasing mental health issues among students [20,39]. Balancing academics and technology—providing students with a ‘safe space’ to purposely ‘disconnect’ may lead to healthier relationships with technology.

- According to Thomas et al. [20], “digital wellness essentially prioritizes the level of self-control one can assert over their usage of digital devices and focuses on aligning them to achieve long-standing goals” [20] (p. 1). Developing mechanisms to address technology addiction and its impact on mental health and purposely promoting technology usage on campus may positively impact students’ wellness.

- Libraries and learning centres could also offer seminars on life skills, such as time management and healthy technology-use strategies.

- As Hollender [40] and Rapanta et al. [36] suggest, the pandemic challenged higher education practices and what we knew about technology. The new ‘normal’, as students return to class, may prompt post-secondary institutions to make technology literacy classes part of foundational courses, educating students on the risks and benefits of using technology and the importance of healthy technology habits to wellness.

- Writing has become a stressor for students. Providing these students with academic writing courses addressing academic norms, language, and culture could lead to growing confidence and possibly better learning outcomes [13].

Ultimately, the curriculum practices discussed in this paper are suggestions to add to the ongoing narrative of technology education, focusing on the rationalization of how to integrate it, in practical terms, into education.

7. The Intersection of Technology, Education, and Wellness

As universities increasingly digitalize how we communicate and share knowledge, online platforms, such as email providers and D2L, have become an extension of the classroom—where students ‘hand in’ assignments, check for class updates, do quizzes, communicate with professors, and often contact other services on campus. In other words, technology has become an intrinsic part of people’s lives, featured in social, personal, educational, and professional aspects of our daily interactions. Asselin et al. [2] and Voyer et al. [35] argue that as technology continues to evolve into intertwined aspects of students’ lives, concerns about its effect on mental and physical health and academic prospects are evident. Ultimately, Flaherty [26] suggests that rethinking the availability, accessibility, and integration of wellness practices in students’ experiences is essential to make wellness a part of the academic experience on campuses.

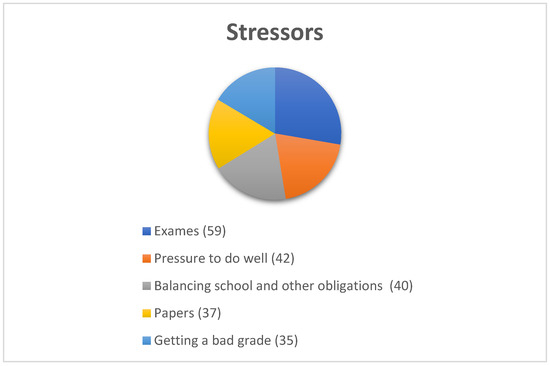

A survey of 3000 students in their second and fourth year of university shows that stress and mental health are major obstacles to academic success [25]. The survey highlights the students’ main areas of concern, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sources of stress for students [25].

Flaherty’s [25] chart shows the main sources of stress students often experience in university: exams, a balance of life and education, papers, as well as social and academic pressures and low grades. In search of addressing stress and mental health issues to balance education and personal life, most higher institutions acknowledge the key role of wellness in education [26]. These institutions offer sports and fitness centres, mental health services where students can access mental health counsellors, and other services, such as academic accessibility services and writing centres. In addition, informal mental health initiatives focusing on socialization, such as student-themed clubs and volunteer support/mentorship groups, are easily seen on campuses.

However, Flaherty [25] argues that 45 percent of students surveyed expect professors to offer mental health support, and 60 percent of these students never used the mental health centres available on campus. Questions remain as to ‘why’ students are not utilizing these campus services and ‘why’ they seem to blame professors for not addressing their mental health problems. Research notes that students transitioning into university often struggle to adapt to university culture and academic requirements [6,12,13]. McCarthy’s [12] still relevant analogy to freshmen students as ‘a stranger in a strange land’ points to the vital difference in students’ academic and social environments as they transition from high school into post-secondary education. This may suggest that in high school, students may rely more on their teachers for academic and personal support and might not know how to navigate services offered on campus, as they are still trying to understand the context and culture of higher education.

Douwes et al. [41] point to the importance of adhering to a holistic approach to students’ academic needs, one that includes wellness. They suggest wellness is found in happiness and the development of one’s full potential. A 2020 study in the Netherlands, coincidently during the COVID-19 pandemic and facilitated by video conference platforms, interviewed students seeking to understand what would contribute to better wellness practices on campus [41]. These students shared their perspectives on defining well-being, which are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Student Perspectives on the Definition of Student Well-being.

This table illustrates the students’ key perspectives on well-being. The study also emphasized the importance of developing self-regulation skills and resilience in students. Research, such as Douwes et al.’s [41] study, may contribute to our understanding of which areas higher education can further focus their efforts on to promote wellness on campus.

In sum, promoting wellness may require aligning academic and non-academic aspects of life goals as an integral part of higher education. This may include:

- Provide support for students regarding cultural and academic aspects of higher institutions, which is especially important for first-year university students [13]. Such aspects include utilizing wellness and academic services available on campus [18].

- Wilson [28] defines formal writing as a life skill. Technology has further stressed the importance of written communications, requiring closer attention to a recurring problem: ‘Many students are ignorant of the role of academic writing and its potential impact on their grades’ [6,12,13]. It highlights how academic papers’ requirements and expectations differ from high school writing practices, which often focus on personal essays. As students are assessed mostly through writing, poor writing skills often lead to low grades [13]. According to Douwes et al. [41], low grades are one of the main stressors for students, impacting wellness.

- A holistic approach to wellness may also be necessary to develop in students the skills they will need for a happy life [41]. It may point to the importance of life skills being a key to a happy life and a core value to wellness. Higher education has an important role in preparing students for adulthood. This holistic approach may consider incorporating aspects of academic and life skills in the curriculum, such as the following:

- Time management—organizational skills, which include understanding that time is a limited commodity and that it has its rules when navigating well-balanced educational, professional, social, and personal needs, require optimizing time [41].

- Reroute the main focus of initial ‘technology literacy education’ from ‘how to use devices’ and ‘how devices are made’ to include technology literacy theory reflecting the concept of technology’s healthy function in students’ lives [2].

Overall, the intersection of the different factors impeding students’ wellness success in education is a long-standing, complex issue. Post-secondary institutions’ awareness of such problems has led to the development of wellness services seeking to attend to students’ diverse needs. However, students’ access and utilization of such services have often proven challenging, requiring a rethinking of how to make wellness an intrinsic part of students’ academic experience.

8. Reflections of an Educator

In closing, the dichotomy of thinking in technology between ‘technophilia and technophobia’ may be one of the major obstacles to addressing wellness in education. Throughout history, such a phenomenon is not uncommon. For instance, the Industrial Revolution was also a complex process that brought benefits and challenges that are still pertinent in society today. Rafferty [42] explains the following on the industrial revolution:

This economic transformation changed not only how work was done, and goods were produced, but it also altered how people related both to one another and to the planet at large. This wholesale change in societal organization continues today, and it has produced several effects that have rippled throughout Earth’s political, ecological, and cultural spheres.[42] (p. 1)

Creating community-based educational spaces that integrate technology as a learning tool while acknowledging the challenges one may encounter as technology increasingly evolves in its potential to become a distraction is key to curbing its negative impact on learning outcomes and students’ well-being. Such a perspective is aligned with concepts described in Suh et al.’s [43] ‘person center’ approach to supporting wellness in technology. Their study suggests an individually centred proactive approach—evaluate and meaningfully recognize students’ struggles with understanding and utilizing technology. Empowering students through technology literacy and providing constructive opportunities for interactions with technology may be vital to supporting students’ mental health. Bhattacharya et al. [3] argue that “social interaction can alleviate stress, worry, and depression; on the other hand, social isolation can be extremely harmful to one’s mental health” [3] (p. 1). These authors suggest that the increasing trend of spending more time on social media platforms than on in-person social interactions may contribute to social isolation and mental health issues.

In conclusion, advances in technology and its increasing role in students’ lives have expanded the conceptualization of wellness to incorporate the challenges and benefits of living with technology. The understanding that education is an integral part of life, as it is mainly affected by developmental and social factors, especially in the context of students transitioning into higher education where technology is interconnected with daily life, prompting a need to rethink education in the context of the interactions with our surroundings, whether they are in-person or virtual, has become a vital part of academic success.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hettler, B. The six dimensions of wellness model. In National Wellness Institute; Six Dimensions of Wellness; National Wellness Institute: Brookfield, WI, USA, 1976; Available online: https://nationalwellness.org/resources/six-dimensions-of-wellness/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Asselin, G.; Bilodeau, H.; Khalid, A. Digital well-being: The relationship between technology use, mental health and interpersonal relationships. Stat. Can. 2024, 1–9. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/22-20-0001/222000012024001-eng.pdf?st=JZUw4Vhv (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Vallabh, V.; Marzo, R.R.; Juyal, R.; Gokdemir, O. Digital well-being through the use of technology: A perspective. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2023, 12, e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, N.A.; Colvin, D.A. Technology, Human Relationships, and Human Interaction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwikel, J.; Cnaan, R. Ethical dilemmas in applying second-wave information technology to social work practice. Soc. Work 1991, 36, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, D. Academic writing and ChatGPT: Students transitioning into college in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. Discov. Educ. 2024, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. CyberSociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, N.H.; Erbring, L. Internet and society: A preliminary report. Stanf. Inst. Quant. Study Soc. 2000, 1, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, S. The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Weizenbaum, J. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, A.; Saunders, K.E.A.; Malhi, G.S.; Patten, S.; Cipriani, A.; McNevin, S.H.; MacDonald, E.; Geddes, J. Mental health care for university students: A way forward? Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, L.P. A stranger in strange lands: A college student writing across the curriculum. Res. Teach. Engl. 1987, 21, 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, L.; Yagelski, R.P. Describing cross-disciplinary academic moves in first-year college student writing. Res. Teach. Engl. 2018, 52, 382–403. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-García, G.; Ramos-Navas-Parejo, M.; de la Cruz-Campos, J.C.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, C. Impact of COVID-19 on university students: An analysis of its influence on psychological and academic factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; Mortier, P.; et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2955–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, A.C.; Fox, J.; McEwan, B. Technology, relationships, and well-being: An overview of critical research issues and an introduction to the special issue. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2024, 41, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. Technophile. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technophile (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Myers, N.D.; Prilleltensky, I.; Lee, S.; Dietz, S.; Prilleltensky, O.; McMahon, A.; Pfeiffer, A.K.; Ellithorpe, E.M.; Brincks, M.A. Effectiveness of the fun for wellness online behavioral intervention to promote well being and physical activity: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, C. Effectiveness of virtual wellness programming for adults with disabilities: Clients’ perspectives. J. Allied Health 2021, 50, 63E–66E. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N.M.; Choudhari, S.G.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Quazi Syed, Z. ‘Digital Wellbeing’: The need of the hour in today’s digitalized and technology driven world! Cureus 2022, 14, e27743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alberta Education. Standards for the Use of Personal Devices and Social Media in Schools. 2024. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/b44bcae6-2e6e-4814-bb25-2e7d7b592b8d/resource/096ddf6b-fc6d-475d-a693-d9fa77aae862/download/educ-standards-use-personal-mobile-devices-social-media-schools-parent-guide-2024-08.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Dobrin, I.S. Talking About Generative AI: A Guide for Educators. Attribution-NonCommertial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International; Creative Commons: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bankins, S.; Jooss, S.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Marrone, M.; Ocampo, A.C.; Shoss, M. Navigating career stages in the age of artificial intelligence: A systematic interdisciplinary review and agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2024, 153, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount Royal University. Wellness Services. Wellness Services|MRU; Mount Royal University: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, C. Survey: Stress undercutting student success. Inside High. Educ. 2023. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/health-wellness/2023/05/17/survey-stress-undercutting-student-success (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Flaherty, C. Physical health and wellness linked to student success. Inside High. Educ. 2023. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/health-wellness/2023/05/31/how-college-students-rate-campus-health-and (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Sandhu, R.K.; Vasconcelos-Gomes, J.; Thomas, M.A.; Oliveira, T. Unfolding the popularity of video conferencing apps—A privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.J. Academic Writing; Harvard Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://wilson.fas.harvard.edu/files/jeffreywilson/files/jeffrey_r._wilson_academic_writing.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Amo Sánchez-Fortún, J.M.d.; Baldrich, K.; Domínguez-Oller, J.C.; Pérez-García, C. Writing in the discipline of education: Beliefs of future teachers regarding their academic literacy. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1422120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, D. Hiring practices and its connection to the conceptualization of ‘a good teacher’ in diverse classrooms. J. Educ. Thought 2020, 53, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Coombs, L.; Luckett, J.; Marin, M.; Olson, P. Risks of AI applications used in higher education. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2024, 22, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Aguilar, S.J.; Bankard, J.S.; Bui, E.; Nye, B. Writing with AI: What college students learned from utilizing ChatGPT for a writing assignment. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A. Vocational education. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 25, pp. 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M. A concept analysis of digital citizenship for democratic citizenship education in the internet age. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2016, 44, 565–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Ronis, S.T.; Byers, N. The effect of notetaking method on academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 68, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Balancing technology, pedagogy and the new normal: Post-pandemic challenges for higher education. Postdigit Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 715–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribble, M. Digital citizenship: Addressing appropriate technology behavior. Learn. Lead. Technol. 2004, 32, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cemiloglu, D.; Basel Almourad, M.; McAlaney, J.; Ali, R. Combatting digital addiction: Current approaches and future directions. Technol. Soc. 2021, 68, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffier, J.; Rehman, A.; Westley, M. Exploring digital wellness perspectives among graduate students. In EDULEARN24 Proceedings, 16th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, 1–3 July 2024; International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED): Palma, Spain, 2024; pp. 3055–3059. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, J.B. The Pandemic Is Taking Higher Education Back to School. University World News. 2021. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210118070559840 (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Douwes, R.; Metselaar, J.; Pijnenborg GH, M.; Boonstra, N. Well-being of students in higher education: The importance of a student perspective. Cogent Educ. 2023, 10, 2190697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, J.P. The Rise of the Machines: Pros and Cons of the Industrial Revolution. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/story/the-rise-of-the-machines-pros-and-cons-of-the-industrial-revolution (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Suh, J.; Pendse, S.R.; Lewis, R.; Howe, E.; Saha, K.; Okoli, E.; Amores, J.; Ramos, G.; Shen, J.; Borghouts, J.; et al. Rethinking technology innovation for mental health: Framework for multi-sectoral collaboration. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).