Viruses and Ticks: An Integrative Review of Virological Findings in Ticks

Abstract

1. Introduction

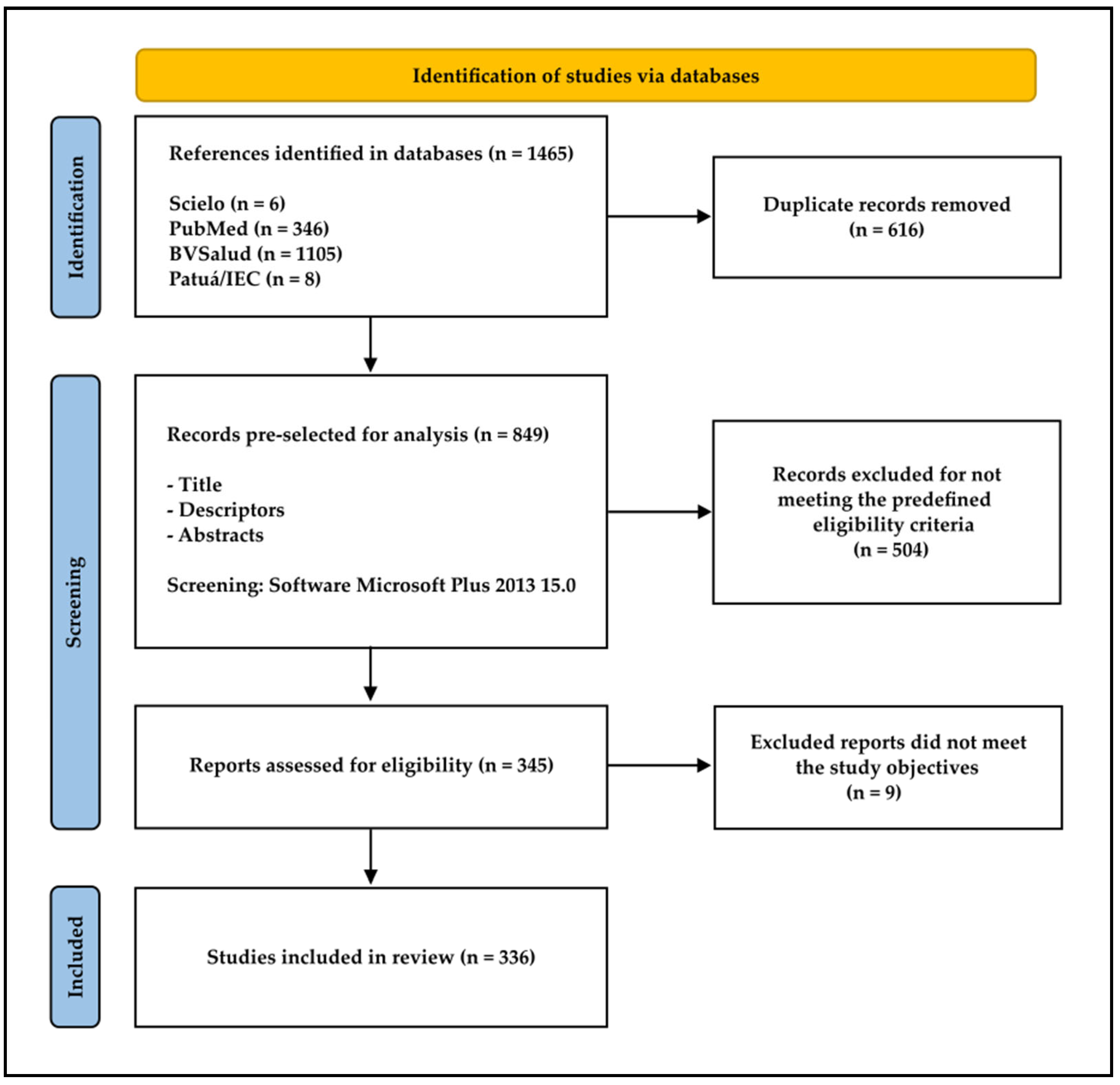

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concept of the Study

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

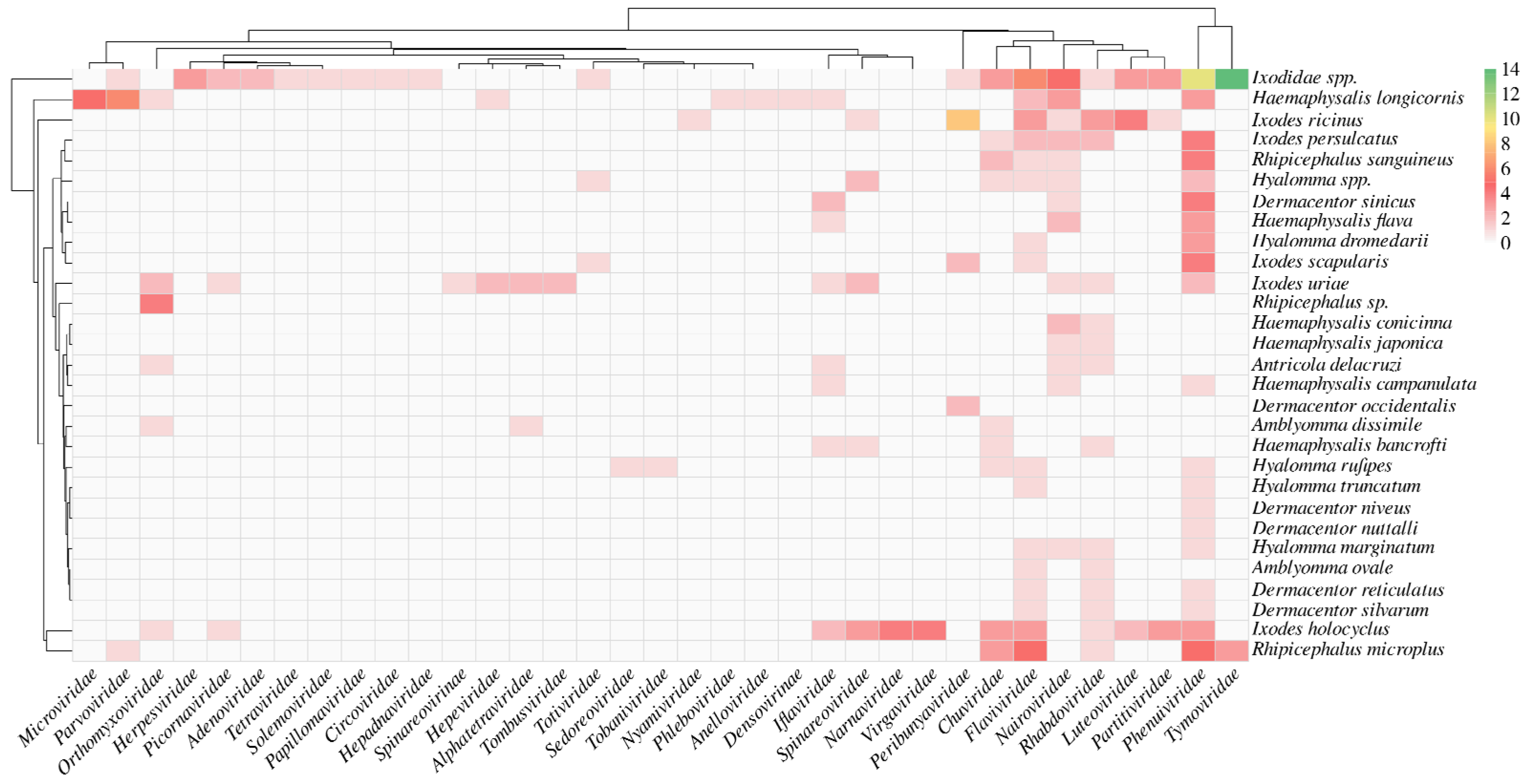

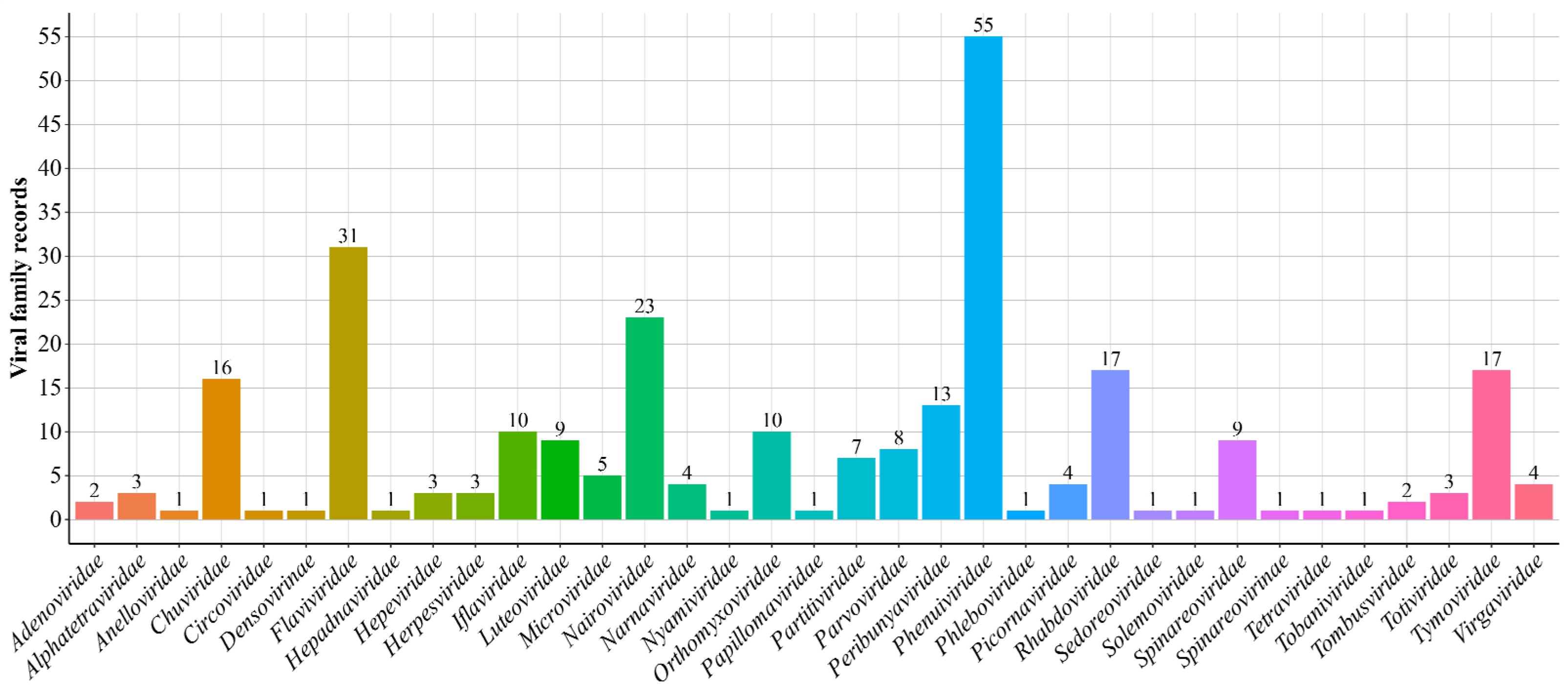

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Family Flaviviridae: Orthoflavivirus

4.1.1. Tick-borne encephalitis virus: Orthoflavivirus encephalitidis

4.1.2. Louping ill virus: Orthoflavivirus loupingi

4.1.3. Powassan virus: Orthoflavivirus powassanense

4.1.4. Kyasanur forest disease virus: Orthoflavivirus kyasanurense

4.1.5. Omsk haemorrhagic fever virus: Orthoflavivirus omskense

4.1.6. West Nile virus: Orthoflavivirus nilense

4.1.7. Kadam virus: Orthoflavivirus kadamense

4.1.8. Langat virus: Orthoflavivirus langatense

4.1.9. Usutu virus: Orthoflavivirus usutuense

4.1.10. Saint Louis encephalitis virus: Orthoflavivirus louisense

4.1.11. Karshi virus: Orthoflavivirus royalense

4.2. Family Nairoviridae: Orthonairovirus

4.2.1. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus: Orthonairovirus haemorrhagiae

4.2.2. Dugbe virus: Orthonairovirus dugbeense

4.2.3. Yezo virus: Orthonairovirus yezoense

4.2.4. Kasokero virus: Orthonairovirus kasokeroense

4.2.5. Nairobi sheep disease orthonairovirus: Orthonairovirus nairobiense

4.2.6. Hazara virus: Orthonairovirus hazaraense

4.2.7. Antu virus: Orthonairovirus antuense

4.2.8. Beiji nairovirus: Norwavirus beijiense

4.3. Family Phenuiviridae

4.3.1. SFTS virus: Dabie bandavirus: Bandavirus dabieense

4.3.2. Heartland virus: Bandavirus heartlandense

4.3.3. Hunter island group virus: Bandavirus albatrossense

4.3.4. Bhanja virus: Bandavirus bhanjanagarense

4.3.5. Dabieshan tick virus: Uukuvirus dabieshanense

4.3.6. Lihan tick virus: Uukuvirus lihanense

4.3.7. Kabuto mountain virus: Uukuvirus kabutoense

4.3.8. Uukuniemi virus: Uukuvirus uukuniemiense

4.3.9. Mukawa virus: Phlebovirus mukawaense

4.4. Family Orthomyxoviridae

4.4.1. Bourbon virus: Thogotovirus bourbonense

4.4.2. Thogoto virus: Thogoto thogotovirus: Thogotovirus thogotoense

4.4.3. Dhori virus: Dhori thogotovirus: Thogotovirus dhoriense

4.5. Family Togaviridae

4.5.1. Semliki forest virus: Alphavirus semliki

4.5.2. Ndumu virus: Alphavirus ndumu

4.6. Family Asfarviridae

African swine fever virus: Asfivirus haemorrhagiae

4.7. Family Poxviridae

4.7.1. Myxomatosum cuniculi virus: Leporipoxvirus myxoma

4.7.2. Milker’s node virus: Pseudocowpox virus: Parapoxvirus pseudocowpox

4.7.3. Bovine papular dermatitis virus: Parapoxvirus bovinestomatitis

4.7.4. Lumpy skin disease virus: Capripoxvirus lumpyskinpox

4.8. Family Arenaviridae

4.8.1. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: Mammarenavirus choriomeningitidis

4.8.2. Tacaribe virus: Mammarenavirus tacaribeense

4.9. Family Sedoreoviridae

4.9.1. Great Island virus: Kemerovo serocomplex: Orbivirus magninsulae

4.9.2. Bluetongue virus: Orbivirus caerulinguae

4.9.3. Murid herpesvirus 4: Rhadinovirus muridgamma4

4.10. Family Spinareoviridae

4.10.1. Eyach virus: Coltivirus ixodis

4.10.2. Colorado tick fever virus: Coltivirus dermacentoris

4.10.3. Kundal virus: Kundal coltivirus: Coltivirus kundalense

4.11. Family Peribunyaviridae

Bunyamwera virus: Orthobunyavirus bunyamweraense

4.12. Family Picornaviridae

Foot-and-mouth disease virus: Aphthovirus vesiculae

4.13. Family Rhabdoviridae

4.13.1. Zahedan rhabdovirus: Zarhavirus zahedan

4.13.2. Barur virus: Ledantevirus barur

4.14. Family Paramyxoviridae

Nipah virus: Henipavirus nipahense

4.15. Ungrouped

4.15.1. Alongshan virus

4.15.2. Yanggou tick virus

4.15.3. Mpulungu flavivirus

4.15.4. Meaban-like virus

4.15.5. Phlebovirus gomselga

4.15.6. Phenuivirus stavropol

4.15.7. Okutama tick virus

4.15.8. Shibuyunji virus

4.15.9. Phlebovirus-like-AYUT

4.15.10. Haseki tick virus

4.15.11. Kindia tick virus

4.15.12. Yichun nairovirus

4.15.13. Kinna virus

4.15.14. Sandy Bay virus

4.16. Climate Change

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization—WHO. Vector-Borne Diseases. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses—ICTV. Current ICTV Taxonomy Release. 2025. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Kleiboeker, S.B.; Scoles, G.A. Pathogenesis of African swine fever virus in Ornithodoros ticks. Anim. Health Res. Ver. 2001, 2, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, N.N.; Madden, D.W.; Wilson, W.C.; Trujillo, J.D.; Richt, J.A. African Swine Fever Virus: An Emerging DNA Arbovirus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, D.A. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE): From tick to pathology. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.M.; Park, S.J. Tick-borne viroses: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and animal models. One Health 2024, 19, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lani, R.; Moghaddam, E.; Haghani, A.; Chang, L.; AbuBakar, S.; Zandi, K. Tick-borne viruses: A review from the perspective of therapeutic approaches. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, K.L.; Jizhou, L.; Phipps, L.P.; Johnson, N. Emerging Tick-Borne Viruses in the Twenty-First Century. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustijanac, E.; Buršić, M.; Talapko, J.; Škrlec, I.; Meštrović, T.; Lišnjić, D. Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Prevention. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gömer, A.; Lang, A.; Janshoff, S.; Steinmann, J.; Steinmann, E. Epidemiology and global spread of emerging tick-borne Alongshan virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2404271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sameroff, S.; Tokarz, R.; Jain, K.; Oleynik, A.; Carrington, C.V.F.; Lipkin, W.I.; Oura, C.A.L. Novel quaranjavirus and other viral sequences identified from ticks parasitizing hunted wildlife in Trinidad and Tobago. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2021, 4, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, J.H.O.; Shi, M.; Bohlin, J.; Eldholm, V.; Brynildsrud, O.B.; Paulsen, K.M.; Andreassen, A.; Holmes, E.C. Characterizing the virome of Ixodes ricinus ticks from northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, A.; Dinçer, E.; Polat, C.; Hekimoğlu, O.; Hacıoğlu, S.; Földes, F.; Özkul, A.; Öktem, I.M.A.; Nitsche, A.; Ergünay, K. A metagenomic survey identifies Tamdy orthonairovirus as well as divergent phlebo-, rhabdo-, chu- and flavi-like viruses in Anatolia, Turkey. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Ding, M.; Tan, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, L.; Wu, J.; He, B.; Tu, C. Virome analysis of tick-borne viruses in Heilongjiang Province, China. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondard, M.; Temmam, S.; Devillers, E.; Pinarello, V.; Bigot, T.; Chrétien, D.; Aprelon, R.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Albina, E.; Eloit, M.; et al. RNA Viruses of Amblyomma variegatum and Rhipicephalus microplus and Cattle Susceptibility in the French Antilles. Viruses 2020, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, J.H.O.; Ellström, P.; Ling, J.; Nilsson, I.; Bergström, S.; González-Acuña, D.; Olsen, B.; Holmes, E.C. Circumpolar diversification of the Ixodes uriae tick virome. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, 1008759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Guo, M.; Hu, B.; Zhou, H.; Yang, W.; Hui, L.; Huang, R.; Zhan, J.; Shi, W.; Wu, Y. Tick virome diversity in Hubei Province, China, and the influence of host ecology. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratuleanu, B.E.; Temmam, S.; Chrétien, D.; Regnault, B.; Pérot, P.; Bouchier, C.; Bigot, T.; Savuța, G.; Eloit, M. The virome of Rhipicephalus, Dermacentor and Haemaphysalis ticks from Eastern Romania includes novel viruses with potential relevance for public health. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 1387–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercole, F.F.; Melo, L.S.; Alcoforado, C.L.G.C. Revisão integrativa versus revisão sistemática. Rev. Min. Enferm. 2014, 18, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.T.; Silva, M.D.; Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, L.L.R.; Cunha, C.C.A.; Macedo, M. O método da revisão integrativa nos estudos organizacionais. Gestão Soc. 2011, 5, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H.J.; Lim, S.M.; Vries, A.; Sprong, H.; Dekker, D.J.; Pascoe, E.L.; Bakker, J.W.; Suin, V.; Franz, E.; Martina, B.E.E.; et al. Continued Circulation of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Variants and Detection of Novel Transmission Foci, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Choi, C.; Lee, L.; Kim, S.; Aknazarov, B.; Nyrgaziev, R.; Atabekova, N.; Jetigenov, E.; Chung, Y.; Lee, H. Molecular Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus from Ticks Collected from Cattle in Kyrgyzstan, 2023. Viruses 2024, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, C.; Hoffmann, B.; Hering, U.; Mielke, B.; Sachse, K.; Beer, M.; Süss, J. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus prevalence and virus genome characterization in field-collected ticks (Ixodes ricinus) from risk, non-risk and former risk areas of TBE, and in ticks removed from humans in Germany. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Laaksonen, M.; Sajanti, E.; Sormunen, J.J.; Penttinen, R.; Hänninen, J.; Ruohomäki, K.; Sääksjärvi, I.; Vesterinen, E.J.; Vuorinen, I.; Hytönen, J.; et al. Crowdsourcing-based nationwide tick collection reveals the distribution of Ixodes ricinus and I. persulcatus and associated pathogens in Finland. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, D.; Ulrich, K.; Ginsbach, P.; Öhme, R.; Bock-Hensley, O.; Falk, U.; Teinert, M.; Lenhard, T. Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) prevalence in field-collected ticks (Ixodes ricinus) and phylogenetic, structural and virulence analysis in a TBE high-risk endemic area in southwestern Germany. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.M.; Song, B.G.; Choi, W.; Park, W.I.; Kim, S.Y.; Roh, J.Y.; Ryou, J.; Ju, Y.R.; Park, C.; Shin, E. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus in ixodid ticks collected from the republic of Korea during 2011-2012. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2012, 3, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topp, A.K.; Springer, A.; Dobler, G.; Bestehorn-Willmann, M.; Monazahian, M.; Strube, C. New and Confirmed Foci of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus (TBEV) in Northern Germany Determined by TBEV Detection in Ticks. Pathogens 2022, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, A.; Pavlidou, V.; Antoniadis, A. Greek Goat Encephalitis Virus Strain Isolated from Ixodes ricinus, Greece. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobitsyn, I.G.; Moskvitina, N.S.; Tyutenkov, O.Y.; Gashkov, S.I.; Kononova, Y.V.; Moskvitin, S.S.; Romanenko, V.N.; Mikryukova, T.P.; Protopopova, E.V.; Kartashov, M.Y.; et al. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in wild birds and their ticks in Western Siberia and high level of their mismatch. Folia Parasitol. 2021, 68, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejek, J.; Marinov, M.; Kiss, B.J.; Alexe, V.; Nowotny, N. The complete sequence of a West Nile virus lineage 2 strain detected in a Hyalomma marginatum marginatum tick collected from a song thrush (Turdus philomelos) in eastern Romania in 2013 revealed closest genetic relationship to strain Volgograd 2007. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, R.; Tagliafierro, T.; Cucura, D.M.; Rochlin, I.; Sameroff, S.; Lipkin, W.I. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan Virus in Ticks by a Multiplex Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay. mSphere 2017, 2, e00151-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez, Z.E.; Rainey, T.; Puelle, R.; Khan, A.; Jordan, R.A.; Egizi, A.M.; Price, D.C. Detection of multiple tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes scapularis from Hunterdon County, NJ, USA. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2023, 4, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.L.; Graham, C.B.; Maes, S.E.; Hojgaard, A.; Fleshman, A.; Boegler, K.A.; Delory, M.J.; Slater, K.S.; Karpathy, S.E.; Bjork, J.K.; et al. Prevalence and distribution of seven human pathogens in host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in Minnesota, USA. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.; Shin, A.; Tukhanova, N.; Turebekov, N.; Nurmakhanov, T.; Sutyagin, V.; Berdibekov, A.; Maikanov, N.; Lezdinsh, I.; Shapiyeva, Z.; et al. First Indications of Omsk Haemorrhagic Fever Virus beyond Russia. Viruses 2022, 14, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vial, L.; Wieland, B.; Jori, F.; Etter, E.; Dixon, L.; Roger, F. African Swine Fever Virus DNA in Soft Ticks, Senegal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1928–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, E.; Machuka, E.; Githae, D.; Okoth, E.; Cleaveland, S.; Shirima, G.; Kusiluka, L.; Pelle, R. Detection of African swine fever virus genotype XV in a sylvatic cycle in Saadani National Park, Tanzania. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 68, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaomanana, J.; Michaud, V.; Jori, F.; Andriatsimahavandy, A.; Roger, F.; Albina, E.; Vial, L. First detection of African Swine Fever Virus in Ornithodoros porcinus in Madagascar and new insights into tick distribution and taxonomy. Parasites Vectors 2010, 3, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Gao, S.; Xin, Q.; Yang, M.; Bi, Y.; Jiang, F.; Zeng, Z.; Kan, W.; Wang, T.; Chen, Q.; et al. Spatial risk of Haemaphysalis longicornis borne Dabieshan tick virus (DBTV) in China. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yin, H.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Bayasgalan, C.; Tserendorj, A.; et al. Discovery and vertical transmission analysis of Dabieshan Tick Virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks from Chengde, China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1365356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Niu, G.; Wang, X.; Ding, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, M.; Bi, Z.; et al. SFTS virus in ticks in an endemic area of China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, F.H.; Gao, Q.T.; Jiang, F.; Liu, B.S.; Shen, G.S.; et al. Identification of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus genotypes in patients and ticks in Liaoning Province, China. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Liang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Jia, L. Survey of tick species and molecular detection of selected tick-borne pathogens in Yanbian, China. Parasite 2022, 29, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Ou, S.C.; Maeda, K.; Shimoda, H.; Chan, J.P.W.; Tu, W.C.; Hsu, W.L.; Chou, C.C. The first discovery of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in Taiwan. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, B.C.; Sutton, W.B.; Moncayo, A.C.; Hughes, H.R.; Taheri, A.; Moore, T.C.; Schweitzer, C.J.; Wang, Y. Heartland Virus in Lone Star Ticks, Alabama, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1954–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuten, H.C.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Noel, K.R.; Hernandez, E.J.; Yates, S.; Wojnowski, K.; Hartleb, J.; Debosik, S.; Holmes, A.; Stone, C.M. Heartland Virus in Humans and Ticks, Illinois, USA, 2018–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziati, I.D.; McFarland, D., Jr.; Antia, A.; Joshi, A.; Aviles-Gamboa, A.; Lee, P.; Harastani, H.; Wang, D.; Adalsteinsson, S.A.; Boon, A.C.M. Prevalence of Bourbon and Heartland viruses in field collected ticks at an environmental field station in St. Louis County, Missouri, USA. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.L.; Scholte, F.E.M.; Ohlendorf, V.; Kopp, A.; Marklewitz, M.; Drosten, C.; Nichol, S.T.; Spiropoulou, C.; Junglen, S.; Bergeron, É. A single mutation in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus discovered in ticks impairs infectivity in human cells. eLife 2020, 9, e50999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, S.; Unicorn, N.M.; Kyeremateng, E.T.; Desewu, G.; Obuam, P.K.; Malm, R.O.T.; Osei-Frempong, E.; Torto, F.A.; Accorlor, S.K.; Boampong, K.; et al. Ticks and tick-borne pathogens in selected abattoirs and a slaughter slab in Kumasi, Ghana. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Barry, Y.; Stoek, F.; Pickin, M.J.; Ba, A.; Chitimia-Dobler, L.; Haki, M.L.; Doumbia, B.A.; Eisenbarth, A.; Diambar, A.; et al. Detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in blood-fed Hyalomma ticks collected from Mauritanian livestock. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, M.; Chinikar, S.; Telmadarraiy, Z.; Vatandoost, H.; Oshaghi, M.A.; Hanafi-Bojd, A.A.; Sedaghat, M.M.; Noroozi, M.; Faghihi, F.; Jalali, T.; et al. Molecular assay on Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in ticks (Ixodidae) collected from Kermanshah Province, Western Iran. J. Arthropod Borne Dis. 2016, 10, 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Moming, A.; Yue, X.; Shen, S.; Chang, C.; Wang, C.; Luo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, R.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in ticks from different ecosystems in Xinjiang, China. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadpour, F.; Telmadarraiy, Z.; Chinikar, S.; Akbarzadeh, K.; Moemenbellah-Fard, M.D.; Faghihi, F.; Fakoorziba, M.R.; Jalali, T.; Mostafavi, E.; Shahhosseini, N.; et al. Molecular detection of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in ticks collected from infested livestock populations in a new endemic area, south of Iran. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Matías, R.; Moraga-Fernández, A.; Peralbo-Moreno, A.; Negredo, A.I.; Sánchez-Seco, M.P.; Ruiz-Fons, F. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in questing non-Hyalomma spp. ticks in Northwest Spain, 2021. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Mukhami, N.N.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Burashev, Y.D.; Zakarya, K.D.; Nakhanov, A.K.; Barakbayev, K.B.; Orynbayev, M.B. The Prevalence and Genetic Variants of the CCHF Virus Circulating among Ticks in the Southern Regions of Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2022, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuivanen, S.; Levanov, L.; Kareinen, L.; Sironen, T.; Jääskeläinen, A.J.; Plyusnin, I.; Zakham, F.; Emmerich, P.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Hepojoki, J.; et al. Detection of novel tick-borne pathogen, Alongshan virus, in Ixodes ricinus ticks, south-eastern Finland, 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1900394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.J.; Lin, X.D.; Chen, Y.M.; Hao, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.X.; Yu, Z.M.; Lu, M.; Li, K.; Qin, X.C.; Wang, W.; et al. Diversity and circulation of Jingmen tick virus in ticks and mammals. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogola, E.O.; Kopp, A.; Bastos, A.D.S.; Slothouwer, I.; Marklewitz, M.; Omoga, D.; Rotich, G.; Getugi, C.; Sang, R.; Torto, B.; et al. Jingmen Tick Virus in Ticks from Kenya. Viruses 2022, 14, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodilov, I.S.; Litov, A.G.; Klimentov, A.S.; Belova, O.A.; Polienko, A.E.; Nikitin, N.A.; Shchetinin, A.M.; Ivannikova, A.Y.; Bell-Sakyi, L.; Yakovlev, A.S.; et al. Isolation and Characterisation of Alongshan Virus in Russia. Viruses 2020, 12, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçer, E.; Hacıoğlu, S.; Kar, S.; Emanet, N.; Brinkmann, A.; Nitsche, A.; Özkul, A.; Linton, Y.M.; Ergünay, K. Survey and Characterization of Jingmen Tick Virus Variants. Viruses 2019, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, R.; Cao, H.; Huang, P.; Yan, H.; Meng, P.; Xiong, Z.; Dai, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, L.; et al. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Jingmen tick virus in Jiangxi Province, China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1375852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodilov, I.S.; Belova, O.A.; Morozkin, E.S.; Litov, A.G.; Ivannikova, A.Y.; Makenov, M.T.; Shchetinin, A.M.; Aibulatov, S.V.; Bazarova, G.K.; Bell-Sakyi, L.; et al. Geographical and tick-dependent distribution of Flavi-like Alongshan and Yanggou tick viruses in Russia. Viruses 2021, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelshin, R.V.; Melnikova, O.V.; Karan, L.S.; Andaev, E.I.; Balakhonov, S.V. Complete genome sequences of four European subtype strains of tick-borne encephalitis virus from Eastern Siberia, Russia. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00609-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M.; Erickson, B.R.; Comer, J.A.; Nichol, S.T.; Rollin, P.E.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Memish, Z.A. Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus Alkhurma Subtype in Ticks, Najran Province, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielová, V.; Holubová, J.; Pejcoch, M.; Daniel, M. Potential significance of transovarial transmission in the circulation of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Folia Parasitol. 2002, 49, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xiao, J.; Moming, A.; Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Chen, C.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Z.; et al. Identification and characterization of new Siberian subtype of tick-borne encephalitis virus isolates revealed genetic variations of the Chinese strains. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2024, 124, 105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurchenko, O.O.; Dubina, D.O.; Vynograd, N.O.; Gonzalez, J.P. Partial characterization of tick-borne encephalitis virus isolates from ticks of Southern Ukraine. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telford, S.R., 3rd; Armstrong, P.M.; Katavolos, P.; Foppa, I.; Garcia, A.S.; Wilson, M.L.; Spielman, A. A new tick-borne encephalitis-like virus infecting New England deer ticks, Ixodes dammini. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1997, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, A.P., 2nd; Peters, R.J.; Prusinski, M.A.; Falco, R.C.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Kramer, L.D. Isolation of deer tick virus (Powassan virus, lineage II) from Ixodes scapularis and detection of antibody in vertebrate hosts sampled in the Hudson Valley, New York State. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, D.M.; Best, J.M.; Mahalingam, S.; Chernesky, M.A.; Wilson, W.E. Powassan virus: Summer infection cycle, 1964. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1964, 91, 1360–1362. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, D.M.; Cobb, C.; Gooderham, S.E.; Smart, C.A.; Wilson, A.G.; Wilson, W.E. Powassan virus: Persistence of virus activity during 1966. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1967, 96, 660–664. [Google Scholar]

- Lwande, O.W.; Lutomiah, J.; Obanda, V.; Gakuya, F.; Mutisya, J.; Mulwa, F.; Michuki, G.; Chepkorir, E.; Fischer, A.; Venter, M.; et al. Isolation of tick and mosquito-borne arboviruses from ticks sampled from livestock and wild animal hosts in Ijara District, Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, Y.; Adcock, K.; Wei, Z.; Mead, D.G.; Kirstein, O.; Bellman, S.; Piantadosi, A.; Kitron, U.; Vazquez-Prokopec, G.M. Isolation of Heartland Virus from Lone Star Ticks, Georgia, USA, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.-M.; Song, B.G.; Choi, W.; Roh, J.Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Park, W.I.; Han, M.G.; Ju, Y.R.; Lee, W.-J. First Isolation of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus from Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks Collected in Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Outbreak Areas in the Republic of Korea. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanein, K.M.; El-Azazy, O.M. Isolation of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus from ticks on imported Sudanese sheep in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2000, 20, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J.; Su, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wang, C.; Abudurexiti, A.; et al. Isolation, characterization, and phylogenetic analysis of two new Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus strains from the northern region of Xinjiang Province, China. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.J.; Pegram, R.G.; Perry, B.D.; Lemche, J.; Schels, H.F. The distribution of African swine fever virus isolated from Ornithodoros moubata in Zambia. Epidemiol. Infect. 1988, 101, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haresnape, J.M.; Wilkinson, P.J.; Mellor, P.S. Isolation of African swine fever virus from ticks of the Ornithodoros moubata complex (Ixodoidea: Argasidae) collected within the African swine fever enzootic area of Malawi. Epidemiol. Infect. 1988, 101, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ličková, M.; Fumačová Havlíková, S.; Sláviková, M.; Slovák, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Klempa, B. Dermacentor reticulatus is a vector of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, K.; Boelke, M.; Grund, D.; Schicht, S.; Springer, A.; Strube, C.; Chitimia-Dobler, L.; Dobler, G.; Jung, K.; Becker, S. Tick populations from endemic and non-endemic areas in Germany show differential susceptibility to TBEV. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, O.A.; Polienko, A.E.; Averianova, A.D.; Karganova, G.G. Hybrids of Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks effectively acquire and transmit tick-borne encephalitis virus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.W.; Esser, H.J.; Sprong, H.; Godeke, G.-J.; Hoornweg, T.E.; de Boer, W.F.; Pijlman, G.P.; Koenraadt, C.J.M. Differential susceptibility of geographically distinct Ixodes ricinus populations to tick-borne encephalitis virus and louping ill virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2321992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migné, C.V.; Seixas, H.B.; Heckmann, A.; Galon, C.; Jaafar, F.M.; Monsion, B.; Attoui, H.; Moutailler, S. Evaluation of vector competence of Ixodes ticks for Kemerovo virus. Viruses 2022, 14, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.S.; Zanluca, C.; Guglielmone, A.A.; Duarte Dos Santos, C.N.; Labruna, M.B.; Diaz, A. Vector competence for West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis virus (Flavivirus) of three tick species of the genus Amblyomma (Acari: Ixodidae). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răileanu, C.; Tauchmann, O.; Vasić, A.; Neumann, U.; Tews, B.A.; Silaghi, C. Transstadial transmission and replication kinetics of West Nile virus lineage 1 in laboratory reared Ixodes ricinus ticks. Pathogens 2020, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, C.H.; Uzcátegui, N.Y.; Gould, E.A.; Nuttall, P.A. Ixodid and argasid tick species and West Nile virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, W.R.; Herslebs, E.J.; Langohr, I.M.; Stone, M.C.; Hermance, M.E. Horizontal and vertical transmission of Powassan virus by the invasive Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, under laboratory conditions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 923914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMinn, R.J.; Gallichotte, E.N.; Courtney, S.; Telford, S.R.; Ebel, G.D. Strain-dependent assessment of Powassan virus transmission to Ixodes scapularis ticks. Viruses 2024, 16, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obellianne, C.; Norman, P.D.; Esteves, E.; Hermance, M.E. Interspecies co-feeding transmission of Powassan virus between a native tick, Ixodes scapularis, and the invasive East Asian tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Cozens, D.W.; Armstrong, P.M.; Brackney, D.E. Vector competence of human-biting ticks Ixodes scapularis, Amblyomma americanum and Dermacentor variabilis for Powassan virus. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.J.; Swanepoel, R.; Shepherd, S.P.; Leman, P.A.; Mathee, O. Viraemic transmission of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus to ticks. Epidemiol. Infect. 1991, 106, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, O.; Cornet, J.P.; Camicas, J.L.; Fontenille, D.; Gonzalez, J.P. [Experimental transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus: Role of 3 vector species in the maintenance and transmission cycles in Senegal]. Parasite 1999, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Hutet, E.; Paboeuf, F.; Duhayon, M.; Boinas, F.; Perez de Leon, A.; Filatov, S.; Vial, L.; Le Potier, M.-F. Comparative vector competence of the Afrotropical soft tick Ornithodoros moubata and Palearctic species, O. erraticus and O. verrucosus, for African swine fever virus strains circulating in Eurasia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Hutet, E.; Lancelot, R.; Paboeuf, F.; Duhayon, M.; Boinas, F.; Pérez de León, A.A.; Filatov, S.; Le Potier, M.-F.; Vial, L. Differential vector competence of Ornithodoros soft ticks for African swine fever virus: What if it involves more than just crossing organic barriers in ticks? Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiboeker, S.B.; Scoles, G.A.; Burrage, T.G.; Sur, J. African swine fever virus replication in the midgut epithelium is required for infection of Ornithodoros ticks. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 8587–8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, W.R.; Perry, J.B.; Hermance, M.E. Transovarial Transmission of Heartland Virus by Invasive Asian Longhorned Ticks under Laboratory Conditions. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.L.; Söder, L.; Kubinski, M.; Glanz, J.; Gregersen, E.; Dümmer, K.; Grund, D.; Wöhler, A.-S.; Könenkamp, L.; Liebig, K.; et al. Detection and Characterization of Alongshan Virus in Ticks and Tick Saliva from Lower Saxony, Germany with Serological Evidence for Viral Transmission to Game and Domestic Animals. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-Sakyi, L.; Růzek, D.; Gould, E.A. Cell lines from the soft tick Ornithodoros moubata. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2009, 49, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciota, A.T.; Payne, A.F.; Kramer, L.D. West Nile virus adaptation to ixodid tick cells is associated with phenotypic trade-offs in primary hosts. Virology 2015, 482, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ciota, A.T.; Payne, A.F.; Ngo, K.A.; Kramer, L.D. Consequences of in vitro host shift for St. Louis encephalitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, B.L.; Grabowski, J.M.; Rosenke, R.; Pulliam, M.; Long, D.R.; Scott, D.P.; Offerdahl, D.K.; Bloom, M.E. Characterization of flavivirus infection in salivary gland cultures from male Ixodes scapularis ticks. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, W.M.; Fumagalli, M.J.; Carrasco, A.O.T.; Romeiro, M.F.; Modha, S.; Seki, M.C.; Gheller, J.M.; Daffre, S.; Nunes, M.R.T.; Murcia, P.R.; et al. Viral diversity of Rhipicephalus microplus parasitizing cattle in southern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, S.; Tokarz, R.; Vucelja, M.; Jain, K.; Oleynik, A.; Boljfetić, M.; Bjedov, L.; Yates, R.A.; Margaletić, J.; Oura, C.A.L.; et al. Virome of Ixodes ricinus, Dermacentor reticulatus, and Haemaphysalis concinna Ticks from Croatia. Viruses 2022, 14, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmüller, S.; Qi, W.; Torgerson, P.R.; Fraefel, C.; Kubacki, J. Hazard potential of Swiss Ixodes ricinus ticks: Virome composition and presence of selected bacterial and protozoan pathogens. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Shen, Q.; Ji, L.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, W.; Gong, H.; Shan, T. Virome diversity of ticks feeding on domestic mammals in China. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Hu, C.; Zhang, D.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Kou, Z.; Fan, Z.; Bente, D.; Zeng, C.; Li, T. Metagenomic profile of the viral communities in Rhipicephalus spp. ticks from Yunnan, China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, G.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Tan, Z.; Tu, C.; He, B. Genomes and seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus and Nairobi sheep disease virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks and goats in Hubei, China. Virology 2019, 529, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tian, X.; Peng, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; et al. Genomic and phylogenetic profiling of RNA of tick-borne arboviruses in Hainan Island, China. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Cai, X.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Fu, L.; Men, X.; Zhu, Y. Virome analysis of ticks and tick-borne viruses in Heilongjiang and Jilin Provinces, China. Virus Res. 2023, 323, 199006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Shi, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Feng, H.; Sun, Y. Diversity of RNA viruses of three dominant tick species in North China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 13, 1057977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Xu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Z.; Sui, L.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, Y.; et al. Extensive diversity of RNA viruses in ticks revealed by metagenomics in northeastern China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0011017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Tian, F.; Han, X.; Liu, L.; Tong, Y. Diversity analysis of tick-associated viruses in northeast China. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Gong, H.; Shen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shan, T.; Yu, X.; Wang, S.J.; Cui, L. Comparison of Viromes in Ticks from Different Domestic Animals in China. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, R.; Tagliafierro, T.; Sameroff, S.; Cucura, D.M.; Oleynik, A.; Che, X.; Jain, K.; Lipkin, W.I. Microbiome Analysis of Ixodes scapularis Ticks from New York and Connecticut. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, S.T.; Kapuscinski, M.L.; Perino, J.; Maertens, B.L.; Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Ebel, G.D.; Stenglein, M.D. Co-Infection Patterns in Individual Ixodes scapularis Ticks Reveal Associations between Viral, Eukaryotic and Bacterial Microorganisms. Viruses 2018, 10, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J.M.; Ng, T.F.F.; Suzuki, Y.; Tsujimoto, H.; Deng, X.; Delwart, E.; Rasgon, J.L. Bunyaviruses are common in male and female Ixodes scapularis ticks in central Pennsylvania. PeerJ 2016, 11, e2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzek, D.; Avšič Županc, T.; Borde, J.; Chrdle, A.; Eyer, L.; Karganova, G.; Kholodilov, I.; Knap, N.; Kozlovskaya, L.; Matveev, A.; et al. Tick-borne encephalitis in Europe and Russia: Review of pathogenesis, clinical features, therapy, and vaccines. Antiviral Res. 2019, 164, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P.; Becher, P.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E.A.; Meyers, G.; Monath, T.; Muerhoff, S.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-Hesse, R.; Smith, D.B.; et al. ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, S.Y.; Mukhacheva, T.A. Reconsidering the classification of tick-borne encephalitis virus within the Siberian subtype gives new insights into its evolutionary history. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 55, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shang, G.; Lu, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, J. A new subtype of eastern tick-borne encephalitis virus discovered in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiyeva, K.; Turebekov, N.; Yegemberdiyeva, R.; Dmitrovskiy, A.; Yeraliyeva, L.; Shapiyeva, Z.; Nurmakhanov, T.; Sansyzbayev, Y.; Froeschl, G.; Hoelscher, M.; et al. Vectors, molecular epidemiology and phylogeny of TBEV in Kazakhstan and central Asia. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Kang, J.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.C.; Klein, T.A.; Chong, S.T.; Sames, W.J.; Yun, S.M.; Ju, Y.R.; Chae, J.S. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus in ticks from southern Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2010, 11, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capligina, V.; Seleznova, M.; Akopjana, S.; Freimane, L.; Lazovska, M.; Krumins, R.; Kivrane, A.; Namina, A.; Aleinikova, D.; Kimsis, J.; et al. Large-scale countrywide screening for tick-borne pathogens in field-collected ticks in Latvia during 2017-2019. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholodilov, I.; Belova, O.; Burenkova, L.; Korotkov, Y.; Romanova, L.; Morozova, L.; Kudriavtsev, V.; Gmyl, L.; Belyaletdinova, I.; Chumakov, A.; et al. Ixodid ticks and tick-borne encephalitis virus prevalence in the South Asian part of Russia (Republic of Tuva). Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffries, C.L.; Mansfield, K.L.; Phipps, L.P.; Wakeley, P.R.; Mearns, R.; Schock, A.; Bell, S.; Breed, A.C.; Fooks, A.R.; Johnson, N. Louping ill virus: An endemic tick-borne disease of Great Britain. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balseiro, A.; Royo, L.J.; Pérez Martínez, C.; Fernández de Mera, I.G.; Höfle, Ú.; Polledo, L.; Marreros, N.; Casais, R.; García Marín, J.F. Louping ill in goats, Spain, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, J.; Willoughby, K.; Underwood, C.; Newman, B.; Mitchell, G.; Carty, H. Encephalitis and neuronal necrosis in a 3-month-old suckled beef calf. Vet. Pathol. 2011, 48, E1–E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, P.J.; Donnelly, W.J.; Clements, L.O.; Fenlon, M. Encephalitis caused by louping ill virus in a group of horses in Ireland. Equine Vet. J. 1976, 8, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerhood, S.; Mansfield, K.L.; Folly, A.J.; Gomez Vitores, A.; Rocchi, M.; Clarke, D.; Gola, C. Meningoencephalomyelitis and brachial plexitis in a dog infected with louping ill virus. Vet. Pathol. 2025, 62, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Oesterle, P.T.; Jardine, C.M.; Dibernardo, A.; Huynh, C.; Lindsay, R.; Pearl, D.L.; Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Nemeth, N.M. Powassan Virus and Other Arthropod-Borne Viruses in Wildlife and Ticks in Ontario, Canada. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klontz, E.H.; Chowdhury, N.; Holbrook, N.; Solomon, I.H.; Telford, S.R., 3rd; Aliota, M.T.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Helgager, J.; Hughes, H.R.; et al. Analysis of Powassan Virus Genome Sequences from Human Cases Reveals Substantial Genetic Diversity with Implications for Molecular Assay Development. Viruses 2024, 16, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.A.; Kennedy, R.C.; Eklund, C.M. Isolation of a virus closely related to Powassan virus from Dermacentor andersoni collected along North Cache la Poudre River, Colo. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1960, 104, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, H.M.; Telford, S.; Goethert, H.K.; Wormser, G.P. Powassan Virus Encephalitis Following Brief Attachment of Connecticut Deer Ticks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2350–e2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermance, M.E.; Thangamani, S. Powassan Virus: An Emerging Arbovirus of Public Health Concern in North America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Powassan Virus Disease. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/powassan/hcp/clinical-signs/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Hoffman, T.; Lindeborg, M.; Barboutis, C.; Erciyas-Yavuz, K.; Evander, M.; Fransson, T.; Figuerola, J.; Jaenson, T.G.T.; Kiat, Y.; Lindgren, P.; et al. Alkhurma Hemorrhagic Fever Virus RNA in Hyalomma rufipes Ticks Infesting Migratory Birds, Europe and Asia Minor. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrel, R.N.; Fagbo, S.; Moureau, G.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Temmam, S.; Lamballerie, X. Alkhurma Hemorrhagic Fever Virus in Ornithodoros savignyi Ticks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, K.C.; Fahmy, N.T.; Watany, N.; Zayed, A.; Mohamed, A.; Ahmed, A.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Dueger, E.L. Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus and Alkhurma (Alkhumra) Virus in Ticks in Djibouti. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Andrade, F.C.D.; Ghosh, S.; Uelmen, J.; Ruiz, M.O. Historical Expansion of Kyasanur Forest Disease in India From 1957 to 2017: A Retrospective Analysis. Geohealth 2019, 3, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munivenkatappa, A.; Sahay, R.R.; Yadav, P.D.; Viswanathan, R.; Mourya, D.T. Clinical & epidemiological significance of Kyasanur forest disease. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2018, 148, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumakov, M. Results of a study made by Omsk hemorrhagic fever (OL) by an expedition of the Institute of Neurology. Vestn. Akad. Med. Nauk. 1948, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever Fact Sheet. 2006. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/25382 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Yastrebov, V.K.; Yakimenko, V.V. The Omsk hemorrhagic fever: Research results (1946–2013). Vopr. Virusol. 2014, 59, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.P.; Hathaway, M.; Demshuk, M.K.; DeHaven, T.O.; Farha, S.M.; Donovan, A.M.; Burdette, A.J.; Walls, G.L.; Selesky, K.M.; Beachboard, D.C.; et al. Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus: Review of the biology, ecology, and disease associated with a historic tick-borne pathogen. Infect. Dis. Immun. 2025, 5, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimidt, J.R.; Said, M.I. Isolation of West Nile Virus from the African Bird Argasid, Argas Reflexus Hermanni, in Egypt. J. Med. Entomol. 1964, 1, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.E.; Tukei, P.M.; McCrae, A.W.; Ssenkubuge, Y.; Mugo, W.N. Virus isolations from Ixodid ticks in Uganda. II. Kadam virus—A new member of arbovirus group B isolated from Rhipicephalus pravus Dontiz. East. Afr. Med. J. 1970, 47, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sang, R.; Onyango, C.; Gachoya, J.; Mabinda, E.; Konongoi, S.; Ofula, V.; Dunster, L.; Okoth, F.; Coldren, R.; Tesh, R.; et al. Tickborne arbovirus surveillance in market livestock, Nairobi, Kenya. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, O.L.; Moussa, M.I.; Hoogstraal, H.; Büttiker, W. Kadam virus (Togaviridae, Flavivirus) infecting camel-parasitizing Hyalomma dromedarii ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Entomol. 1982, 19, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirya, B.G.; Hewitt, L.E.; Sekyalo, E.; Mujomba, A. Arbovirus serology. East. Afr. Virus Res. Inst. Rep. 1970, 19, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogstraal, H. The epidemiology of tick-borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Asia, Europe, and Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 1979, 15, 307–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.G. A virus resembling Russian spring-summer encephalitis virus from an ixodid tick in Malaya. Nature 1956, 178, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobler, G. Zoonotic tick-borne flaviviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J. The Vector Competence of Asian Longhorned Ticks in Langat Virus Transmission. Viruses 2024, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talactac, M.R.; Yoshii, K.; Hernandez, E.P.; Kusakisako, K.; Galay, R.L.; Fujisaki, K.; Mochizuki, M.; Tanaka, T. Synchronous Langat Virus Infection of Haemaphysalis longicornis Using Anal Pore Microinjection. Viruses 2017, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Rajendran, K.V.; Neelakanta, G.; Sultana, H. An Experimental Murine Model to Study Acquisition Dynamics of Tick-Borne Langat Virus in Ixodes scapularis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 849313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, A.; Ruiz, S.; Herrero, L.; Moreno, J.; Molero, F.; Magallanes, A.; Sánchez-Seco, M.P.; Figuerola, J.; Tenorio, A. West Nile and Usutu viruses in mosquitoes in Spain, 2008–2009. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 85, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzolari, M.; Bonilauri, P.; Bellini, R.; Albieri, A.; Defilippo, F.; Maioli, G.; Galletti, G.; Gelati, A.; Barbieri, I.; Tamba, M.; et al. Evidence of simultaneous circulation of West Nile and Usutu viruses in mosquitoes sampled in Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) in 2009. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzolari, M.; Bonilauri, P.; Bellini, R.; Albieri, A.; Defilippo, F.; Tamba, M.; Tassinari, M.; Gelati, A.; Cordioli, P.; Angelini, P.; et al. Usutu virus persistence and West Nile virus inactivity in the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) in 2011. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, J.W.; Münger, E.; Esser, H.J.; Sikkema, R.S.; de Boer, W.F.; Sprong, H.; Reusken, C.B.E.M.; de Vries, A.; Kohl, R.; van der Linden, A.; et al. Ixodes ricinus as potential vector for Usutu virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, V.; Barbić, L.; Bogdanić, M.; Rončević, I.; Klobučar, A.; Medić, A.; Vilibić-Čavlek, T. Zoonotic Orthoflaviviruses Related to Birds: A Literature Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, D.K.; Neronov, V.M.; Gromashevsky, V.L.; Skvortsova, T.M.; Berezina, L.K.; Sidorova, G.A.; Zhmaeva, Z.M.; Gofman, Y.A.; Klimenko, S.M.; Fominam, K.B. “Karshi” virus, a new flavivirus (Togaviridae) isolated from Ornithodoros papillipes (Birula, 1895) ticks in Uzbek S.S.R. Arch. Virol. 1976, 50, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Yang, J.; Moming, A.; Zhang, Y.; Bell-Sakyi, L.; et al. Discovery of Tick-Borne Karshi Virus Implies Misinterpretation of the Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Seroprevalence in Northwest China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 872067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H. Antigenic classification and taxonomy of flaviviruses (family Flaviviridae) emphasizing a universal system for the taxonomy of viruses causing tick-borne encephalitis. Acta Virol. 1988, 32, 469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Gritsun, T.S.; Nuttall, P.A.; Gould, E.A. Tick-borne flaviviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2003, 61, 317–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turell, M.J. Experimental transmission of Karshi (Mammalian Tick-Borne Flavivirus Group) virus by Ornithodoros ticks >2,900 days after initial virus exposure supports the role of soft ticks as a long-term maintenance mechanism for certain flaviviruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, A.R.; Alkhovsky, S.V.; Avšič-Županc, T.; Bente, D.A.; Bergeron, É.; Burt, F.; Di Paola, N.; Ergünay, K.; Hewson, R.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Nairoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 798–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, T.M.; Linthicum, K.J.; Bailey, C.L.; Watts, D.M.; Moulton, J.R. Experimental transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus by Hyalomma truncatum Koch. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1989, 40, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparagano, O.A.; Allsopp, M.T.; Mank, R.A.; Rijpkema, S.G.; Figueroa, J.V.; Jongejan, F. Molecular detection of pathogen DNA in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae): A review. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1999, 23, 929–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasi, K.K.; von Arnim, F.; Schulz, A.; Rehman, A.; Chudhary, A.; Oneeb, M.; Sas, M.A.; Jamil, T.; Maksimov, P.; Sauter-Louis, C.; et al. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in ticks collected from livestock in Balochistan, Pakistan. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badji, A.; Ndiaye, M.; Gaye, A.; Dieng, I.; Ndiaye, E.H.; Dolgova, A.S.; Mhamadi, M.; Diouf, B.; Dia, I.; Dedkov, V.G.; et al. Detection of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus from livestock ticks in northern, central and southern Senegal in 2021. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchetgna, H.S.; Yousseu, F.S.; Cosset, F.L.; Freitas, N.B.; Kamgang, B.; McCall, P.J.; Ndip, R.N.; Legros, V.; Wondji, C.S. Molecular and serological evidence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus prevalence in livestock and ticks in Cameroon. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1132495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appannanavar, S.B.; Mishra, B. An Update on Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2011, 3, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zé-Zé, L.; Nunes, C.; Sousa, M.; de Sousa, R.; Gomes, C.; Santos, A.S.; Alexandre, R.T.; Amaro, F.; Loza, T.; Blanco, M.; et al. Fatal Case of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever, Portugal, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causey, O.R. Supplement to the Catalogue of Arthropod-borne viroses. In Catalogue of Arthropod-Borne and Selected Vertebrate Viruses of the World. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970, 20, 1017–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye, M.; Badji, A.; Dieng, I.; Dolgova, A.S.; Mhamadi, M.; Kirichenko, A.D.; Gladkikh, A.S.; Gaye, A.; Faye, O.; Sall, A.A.; et al. Molecular Detection and Genetic Characterization of Two Dugbe Orthonairovirus Isolates Detected from Ticks in Southern Senegal. Viruses 2024, 16, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.L.; Causey, O.R.; Carey, D.E.; Reddy, S.; Cooke, A.R.; Akinkugbe, F.M.; David-West, T.S.; Kemp, G.E. Arthropod-borne viral infections of man in Nigeria, 1964–1970. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1975, 69, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomori, O.; Monath, T.P.; O’Connor, E.H.; Lee, V.H.; Cropp, C.B. Arbovirus infections among laboratory personnel in Ibadan, Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1981, 30, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, F.J.; Spencer, D.C.; Leman, P.A.; Patterson, B.; Swanepoel, R. Investigation of tick-borne viruses as pathogens of humans in South Africa and evidence of Dugbe virus infection in a patient with prolonged thrombocytopenia. Epidemiol. Infect. 1996, 116, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, F.; Yamaguchi, H.; Park, E.; Tatemoto, K.; Sashika, M.; Nakao, R.; Terauchi, Y.; Mizuma, K.; Orba, Y.; Kariwa, H.; et al. A novel nairovirus associated with acute febrile illness in Hokkaido, Japan. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Minamikawa, M.; Kovba, A.; Numata, H.; Itoh, T.; Ariizumi, T.; Shigeno, A.; Katada, Y.; Niwa, S.; Taya, Y.; et al. Environmental and host factors underlying tick-borne virus infection in wild animals: Investigation of the emerging Yezo virus in Hokkaido, Japan. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2024, 15, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, A.; Tatemoto, K.; Ishijima, K.; Inoue, Y.; Park, E.-S.; Yamamoto, T.; Taira, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Virhuez-Mendoza, M.; Harada, M.; et al. Transboundary Movement of Yezo Virus via Ticks on Migratory Birds, Japan, 2020–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2674–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, A.J.; Amman, B.R.; Patel, K.; Sealy, T.K.; Swanepoel, R.; Towner, J.S. Human-Pathogenic Kasokero Virus in Field-Collected Ticks. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2944–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, E. On a tick-borne gastroenteritis of sheep and goats occurring in British east Africa. J. Comp. Pathol. Ther. 1917, 30, 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.V.; Geevarghese, G.; Joshi, G.D.; Ghodke, Y.S.; Mourya, D.T.; Mishra, A.C. Isolation of Ganjam virus from ticks collected off domestic animals around Pune, Maharashtra, India. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; He, B.; Wang, Z.; Shang, L.; Wei, F.; Liu, Q.; Tu, C. Nairobi sheep disease virus RNA in ixodid ticks, China, 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.K.; Chanas, A.C.; Squires, E.J.; Shockley, P.; Simpson, D.I.; Parsons, J.; Smith, D.H.; Casals, J. Arbovirus isolations from ixodid ticks infesting livestock, Kano Plain, Kenya. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1980, 74, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasteva, S.; Jara, M.; Frias-De-Diego, A.; Machado, G. Nairobi Sheep Disease Virus: A Historical and Epidemiological Perspective. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, C. Nairobi sheep disease. In Infectious Dieases of Livestock with Special Reference to Southern Africa; Coetzer, J.A.W., Thomson, G.R., Tustin, R.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 1994; pp. 718–722. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, F.; Wisseman, C.L., Jr.; Casals, J. Tick-borne viruses of West Pakistan. II. Hazara virus, a new agent isolated from Ixodes redikorzevi ticks from the Kaghan Valley, W. Pakistan. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1970, 92, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, M.A.; Hoogstraal, H.; Roberts, T.J.; Ghazi, R.; Amer, T. A sero-epidemiological survey for Bunyaviridae and certain other arboviruses in Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983, 77, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flusin, O.; Vigne, S.; Peyrefitte, C.N.; Bouloy, M.; Crance, J.M.; Iseni, F. Inhibition of Hazara nairovirus replication by small interfering RNAs and their combination with ribavirin. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.H.; Wiley, M.R.; Rodriguez, S.E.; Bào, Y.; Prieto, K.; Travassos da Rosa, A.P.A.; Guzman, H.; Savji, N.; Ladner, J.T.; Tesh, R.B.; et al. Genomic characterization of the genus Nairovirus (Family Bunyaviridae). Viruses 2016, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan-Yazıcı, M.; Karaaslan, E.; Çetin, N.S.; Hasanoğlu, S.; Güney, F.; Zeybek, Ü.; Doymaz, M.Z. Cross-reactive anti-nucleocapsid protein immunity against Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Hazara virus in multiple species. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e02156-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, J.; Song, J.; Yin, Q.; Nie, K.; Xu, S.; He, Y.; Fu, S.; Liang, G.; Wei, Q.; et al. Novel Orthonairovirus Isolated from Ticks near China–North Korea Border. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1254–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moming, A.; Shen, S.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Li, T.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Evidence of human exposure to Tamdy virus, Northwest China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 3166–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Xie, S.; Jiang, M.; Song, R.; Ma, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, K.; et al. A tentative Tamdy orthonairovirus related to febrile illness in northwestern China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lv, X.-L.; Zhang, X.; Han, S.-Z.; Wang, Z.-D.; Li, L.; Sun, H.-T.; Ma, L.-X.; Cheng, Z.-L.; Shao, J.-W.; et al. Identification of a new orthonairovirus associated with human febrile illness in China. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, M.; Itakura, Y.; Tabata, K.; Komagome, R.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ogasawara, K.; Nakao, R.; Qiu, Y.; Sato, K.; Kawabata, H.; et al. A wide distribution of Beiji nairoviruses and related viruses in Ixodes ticks in Japan. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2024, 15, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Wei, Z.; Lv, X.; Han, S.; Wang, Z.-D.; Fan, C.; Zhang, X.; Shao, J.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Sui, L.; et al. A new nairo-like virus associated with human febrile illness in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomizo, K.; Tomozane, M.; Sano, C.; Ohta, R. Clinical presentation and mortality of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan: A systematic review of case reports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.R.; Heo, S.T.; Song, S.W.; Bae, S.G.; Lee, S.; Choi, S.; Lee, C.; Jeong, S.; Kim, M.; Sa, W.; et al. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus in Ticks and SFTS Incidence in Humans, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2292–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.-J.; Liang, M.-F.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.-D.; Sun, Y.-L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.-F.; Popov, V.L.; Li, C.; et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-J.; Li, J.-D.; Ding, S.-J.; Zhang, Q.-F.; Qu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Wu, W.; Jiang, M.; et al. Isolation, identification and characterization of SFTS bunyavirus from ticks collected on the surface of domestic animals. Bing Du Xue Bao 2012, 28, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-H.; Park, S.-J. Emerging tick-borne Dabie bandavirus: Virology, epidemiology, and prevention. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, W.; Kim, H.C.; Chong, S.T.; Chang, K.S.; Coburn, J.M.; Klein, T.A.; Lee, W.J. Molecular detection of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome and tick-borne encephalitis viruses in ixodid ticks collected from vegetation, Republic of Korea, 2014. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Noh, B.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, T.; Song, B.; Lee, H.I. Nationwide Temporal and Geographical Distribution of Tick Populations and Phylogenetic Analysis of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus in Ticks in Korea, 2020. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Casel, M.A.B.; Jang, S.; Choi, J.H.; Gil, J.; Rollon, R.; Cheun, S.Y.; Kim, Y.; Song, M.S.; Choi, Y.K. Seasonal dynamics of Haemaphysalis tick species as SFTSV vectors in South Korea. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0048924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yu, P.; Chowell, G.; Li, S.; Wei, J.; Tian, H.; Lv, W.; Han, Z.; Yang, J.; Huang, S.; et al. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus in Humans, Domesticated Animals, Ticks, and Mosquitoes, Shaanxi Province, China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 1346–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, Y.; Azama, Y.; Kyan, H.; Fukuchi, Y.; Maeshiro, N.; Kakita, T.; Miyahira, M.; Kudeken, T.; Nidaira, M. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus RNA in Ticks from Wild Mongooses in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, G.; Li, J.; Liang, M.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, M.; Yin, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, C.; et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus among domesticated animals, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, H.M.; Godsey, M.S.; Lambert, A.; Panella, N.A.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Harmon, J.R.; Lash, R.R.; Ashley, D.C.; Nicholson, W.L. First detection of heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) from field collected arthropods. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Heartland Virus Disease. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heartland-virus/hcp/clinical-diagnosis/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Wang, J.; Selleck, P.; Yu, M.; Ha, W.; Rootes, C.; Gales, R.; Wise, T.; Crameri, S.; Chen, H.; Broz, I.; et al. Novel Phlebovirus with Zoonotic Potential Isolated from Ticks, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubálek, Z. Biogeography of tick-borne Bhanja virus (Bunyaviridae) in Europe. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009, 2009, 372691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiler, M.; Downs, W.G. The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates. In The Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hubálek, Z. Experimental pathogenicity of Bhanja virus. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. 1987, 266, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-X.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.-H.; Lin, X.-D.; Kang, Y.-J.; Chen, L.-J.; Qin, X.-C.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. eLife 2015, 4, e05378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Pang, Z.; Liu, L.; Ma, Q.; Han, Y.; Guan, Z.; Qin, H.; Niu, G. Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of a Novel Tick-Borne Virus in Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces, Southwestern China. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; He, T.; Wu, T.; Ai, L.; Hu, D.; Yang, X.; Lv, R.; Yang, L.; Lv, H.; Tan, W. Distribution and phylogenetic analysis of Dabieshan tick virus in ticks collected from Zhoushan, China. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 1226–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Pang, Z.; Fu, H.; Chang, R.; Lin, Z.; Lv, A.; Wang, S.; Kong, X.; Luo, M.; Liu, X.; et al. Identification of recently identified tick-borne viruses (Dabieshan tick virus and SFTSV) by metagenomic analysis in ticks from Shandong Province, China. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekata, H.; Kobayashi, I.; Okabayashi, T. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of Dabieshan tick virus and Okutama tick virus in ticks collected from Cape Toi, Japan. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Chang, R.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, H.; Niu, G. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of a novel tick-borne virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks and sheep from Shandong, China. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, Y.; Miranda, J.; Mattar, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Rovnak, J. First report of Lihan Tick virus (Phlebovirus, Phenuiviridae) in ticks, Colombia. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Hoyos, K.; Montoya-Ruíz, C.; Aguilar, P.V.; Pérez-Doria, A.; Díaz, F.J.; Rodas, J.D. Virome analyses of Amblyomma cajennense and Rhipicephalus microplus ticks collected in Colombia. Acta Trop. 2024, 253, 107158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiri, H.; Lim, C.-K.; Isawa, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Fujita, R.; Takayama-Ito, M.; Kuwata, R.; Kobayashi, D.; Horiya, M.; Posadas-Herrera, G.; et al. Isolation and characterization of Kabuto Mountain virus, a new tick-borne phlebovirus from Haemaphysalis flava ticks in Japan. Virus Res. 2018, 244, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.B.; Shimoda, H.; Mizuno, J.; Ishijima, K.; Yonemitsu, K.; Minami, S.; Supriyono; Kuroda, Y.; Tatemoto, K.; Mendoza, M.V.; et al. Epidemiological study of Kabuto Mountain virus, a novel uukuvirus, in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikku, O.; Brummer-Korvenkontio, M. Arboviruses in Finland: II. Isolation and Characterization of Uukuniemi Virus, a Virus Associated with Ticks and Birds. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 22, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazelier, M.; Rouxel, R.N.; Zumstein, M.; Mancini, R.; Bell-Sakyi, L.; Lozach, P.-Y. Uukuniemi virus as a tick-borne virus model. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 6784–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereventsova, A.V.; Klimentov, A.S.; Kholodilov, I.S.; Belova, O.A.; Butenko, A.M.; Karganova, G.G. Real-time polymerase chain reaction systems for detection and differentiation of unclassified viruses of the Phenuiviridae family. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuno, K.; Kajihara, M.; Nakao, R.; Nao, N.; Mori-Kajihara, A.; Muramatsu, M.; Qiu, Y.; Torii, S.; Igarashi, M.; Kasajima, N.; et al. The Unique Phylogenetic Position of a Novel Tick-Borne Phlebovirus Ensures an Ixodid Origin of the Genus Phlebovirus. mSphere 2018, 3, e00239-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-N.; Jiang, R.-R.; Ding, H.; Zhang, X.-L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.-J.; Zhang, P.-H.; Li, H.; et al. First Detection of Mukawa Virus in Ixodes persulcatus and Haemaphysalis concinna in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 791563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, H.M.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Godsey, M.S., Jr.; Panella, N.A.; Ashley, D.C.; Nicholson, W.L.; Lambert, A.J. Bourbon virus in field-collected ticks, Missouri, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 2017–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsey, M.S.; Rose, D.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Breuner, N.; Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Kosoy, O.I.; Savage, H.M. Experimental Infection of Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) With Bourbon Virus (Orthomyxoviridae: Thogotovirus). J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, R.G.; White, D.J. New distribution records of Amblomma americanum (L.) (Acari: Ixodidae) in New York state. J. Vector Ecol. 1997, 22, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, T.L.; Shafiuddin, M.; Gounder, A.P.; Janowski, A.B.; Zhao, G.; Williams, G.D.; Jagger, B.W.; Diamond, M.S.; Bailey, T.; Kwon, J.H.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of favipiravir against Bourbon virus in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, A.P., 2nd; Prusinski, M.A.; O’Connor, C.; Maffei, J.G.; Koetzner, C.A.; Zembsch, T.E.; Zink, S.D.; White, A.L.; Santoriello, M.P.; Romano, C.L.; et al. Bourbon virus transmission, New York, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, D.A.; Woodall, J.P.; Danskin, D. Thogoto virus: A hitherto underscribed agent isolated from ticks in Kenya. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1965, 38, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, K.; Okamoto, N.; Nakao, R.; Hofstetter, R.K.; Yabu, T.; Masumoto, H.; Someya, A.; Kariwa, H.; Maeda, A. Isolation of the Thogoto virus from a Haemaphysalis longicornis in Kyoto City, Japan. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talactac, M.R.; Yoshii, K.; Hernandez, E.P.; Kusakisako, K.; Galay, R.L.; Fujisaki, K.; Mochizuki, M.; Tanaka, T. Vector competence of Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks for a Japanese isolate of the Thogoto virus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutomiah, J.; Musila, L.; Makio, A.; Ochieng, C.; Koka, H.; Chepkorir, E.; Mutisya, J.; Mulwa, F.; Khamadi, S.; Miller, B.R.; et al. Ticks and tick-borne viruses from livestock hosts in arid and semiarid regions of the eastern and northeastern parts of Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 2014, 51, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithburn, K.C.; Haddow, A.J. Semliki forest virus. Am. Assoc. Immunol. 1944, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, B.M.; Worth, C.B.; Kokernot, R.H. Isolation of Semliki Forest virus from Aedes (Aedimorphus) argenteopunctatus (Theobald) collected in Portuguese East Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1961, 55, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubálek, Z.; Rudolf, I.; Nowotny, N. Chapter Five—Arboviruses Pathogenic for Domestic and Wild Animals. Adv. Virus Res. 2014, 89, 201–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokernot, R.H.; McIntosh, B.M.; Worth, C.B. Ndumu virus, a hitherto unknown agent, isolated from culicine mosquitoes collected in northern Natal, Union of South Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1961, 10, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutomiah, J.; Ongus, J.; Linthicum, K.J.; Sang, R. Natural vertical transmission of Ndumu virus in Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes collected as larvae. J. Med. Entomol. 2014, 51, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, C.; Lutomiah, J.; Makio, A.; Koka, H.; Chepkorir, E.; Yalwala, S.; Mutisya, J.; Musila, L.; Khamadi, S.; Richardson, J.; et al. Mosquito-borne arbovirus surveillance at selected sites in diverse ecological zones of Kenya; 2007–2012. Virol. J. 2013, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, E.H.; Diallo, D.; Fall, G.; Ba, Y.; Faye, O.; Dia, I.; Diallo, M. Arboviruses isolated from the Barkedji mosquito-based surveillance system, 2012–2013. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.F.; Schade-Weskott, M.L.; Rametse, T.; Heath, L.; Kriel, G.J.P.; Klerk-Lorist, L.; Schalkwyk, L.; Trujillo, J.D.; Crafford, J.E.; Richt, J.A.; et al. Detection of African Swine Fever Virus in Ornithodoros Tick Species Associated with Indigenous and Extralimital Warthog Populations in South Africa. Viruses 2022, 14, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Otte, J.; Madeira, S.; Hutchings, G.H.; Boinas, F. Experimental Infection of Ornithodoros erraticus sensu stricto with Two Portuguese African Swine Fever Virus Strains: Study of Factors Involved in the Dynamics of Infection in Ticks. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golnar, A.J.; Martin, E.; Wormington, J.D.; Kading, R.C.; Teel, P.D.; Hamer, S.A.; Hamer, G.L. Reviewing the potential vectors and hosts of African swine fever virus transmission in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019, 19, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pereira, S.; González-Barrio, D.; Fernández-García, L.J.; Gómez-Martín, A.; Habela, M.A.; García-Bocanegra, I.; Calero-Bernal, R. Detection of Myxoma Virus DNA in Ticks from Lagomorph Species in Spain Suggests Their Possible Role as Competent Vector in Viral Transmission. J. Wildl. Dis. 2021, 57, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, P.J.; Liu, J.; Cattadori, I.; Ghedin, E.; Read, A.F.; Holmes, E.C. Myxoma virus and the Leporipoxviruses: An evolutionary paradigm. Viruses 2015, 7, 1020–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanarelli, G. Das myxomatogene Virus. Beitrag zum Stadium der Krankheitserreger ausserhalb des Sichtbaren. Zentrabl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. Infektienskrankh. Hyg. 1898, 23, 865–873. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, A.; Luciani, L.; Zannou, O.; Biguezoton, A.; Pezzi, L.; Thirion, L.; Belem, A.; Saegerman, C.; Charrel, R.; Lempereur, L. Detection of Two Species of the Genus Parapoxvirus (Bovine Papular Stomatitis Virus and Pseudocowpox Virus) in Ticks Infesting Cattle in Burkina Faso. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicculli, V.; Ayhan, N.; Luciani, L.; Pezzi, L.; Maitre, A.; Decarreaux, D.; de Lamballerie, X.; Paoli, J.-C.; Vial, L.; Charrel, R.; et al. Molecular detection of parapoxvirus in Ixodidae ticks collected from cattle in Corsica, France. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, N.; Hopker, A.; Prajapati, G.; Rahangdale, N.; Gore, K.; Sargison, N. Observations on presumptive lumpy skin disease in native cattle and Asian water buffaloes around the tiger reserves of the central Indian highlands. N. Z. Vet. J. 2022, 70, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ansary, R.E.; El-Dabae, W.H.; Bream, A.S.; El Wakil, A. Isolation and molecular characterization of lumpy skin disease virus from hard ticks, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus in Egypt. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppurainen, E.S.M.; Venter, E.H.; Coetzer, J.A.W.; Bell-Sakyi, L. Lumpy skin disease: Attempted propagation in tick cell lines and presence of viral DNA in field ticks collected from naturally-infected cattle. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2015, 6, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Shynybekova, G.O.; Issabek, A.U.; Mukhami, N.N.; Melisbek, A.M.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Kozhabergenov, N.S.; Barmak, S.M.; Bopi, A.K.; Omarova, Z.D.; et al. The Prevalence of Pathogens among Ticks Collected from Livestock in Kazakhstan. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeedan, G.S.G.; Abdalhamed, A.M.; Allam, A.M.; Abdel-Shafy, S. Molecular detection of lumpy skin disease virus in naturally infected cattle and buffaloes: Unveiling the role of tick vectors in disease spread. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 3921–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuppurainen, E.S.M.; Stoltsz, W.H.; Troskie, M.; Wallace, D.B.; Oura, C.A.L.; Mellor, P.S.; Coetzer, J.A.W.; Venter, E.H. A potential role for ixodid (hard) tick vectors in the transmission of lumpy skin disease virus in cattle. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, C.; Matsuura, Y.; Fujii, H.; Joh, K.; Baba, K.; Kato, M.; Hisada, M. Isolation of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus from wild house mice (Mus musculus) in Osaka Port, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1991, 53, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- N’Dilimabaka, N.; Berthet, N.; Rougeron, V.; Mangombi, J.B.; Durand, P.; Maganga, G.D.; Bouchier, C.; Schneider, B.S.; Fair, J.; Renaud, F.; et al. Evidence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) in domestic mice in Gabon: Risk of emergence of LCMV encephalitis in Central Africa. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, A.; de Thoisy, B.; Tirera, S.; Donato, D.; Bouchier, C.; Catzeflis, F.; Lacoste, V. Identification of lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus in house mouse (Mus musculus, Rodentia) in French Guiana. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 37, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthius, D.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: An underrecognized cause of neurologic disease in the fetus, child, and adult. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2012, 19, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wei, F. Molecular detection and phylogenetic analysis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in ticks in Jilin Province, northeastern China. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 85, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Huang, S.J.; Wang, Z.D.; Wei, F.; Feng, X.M.; Jiang, D.X.; Liu, Q. Isolation and genomic characterization of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in ticks from northeastern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayler, K.A.; Barbet, A.F.; Chamberlain, C.; Clapp, W.L.; Alleman, R.; Loeb, J.C.; Lednicky, J.A. Isolation of Tacaribe virus, a Caribbean arenavirus, from host-seeking Amblyomma americanum ticks in Florida. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schountz, T. Unraveling the mystery of Tacaribe virus. mSphere 2024, 9, e0060524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.J.; Downs, W.G.; Shope, R.E.; Wallis, R.C. Great Island and Bauline: Two new Kemerovo group orbiviruses from Ixodes uriae in eastern Canada. J. Med. Entomol. 1973, 10, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejiri, H.; Lim, C.K.; Isawa, H.; Kuwata, R.; Kobayashi, D.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Takayama-Ito, M.; Kinoshita, H.; Kakiuchi, S.; Horiya, M.; et al. Genetic and biological characterization of Muko virus, a new distinct member of the species Great Island virus (genus Orbivirus, family Reoviridae), isolated from ixodid ticks in Japan. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 2965–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, R.M. The transmission of blue-tongue and horse-sickness by Culicoides. J. Vet. Anim. Ind. 1944, 19, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Saminathan, M.; Singh, K.P.; Khorajiya, J.H.; Dinesh, M.; Vineetha, S.; Maity, M.; Rahman, A.F.; Misri, J.; Malik, Y.S.; Gupta, V.K.; et al. An updated review on bluetongue virus: Epidemiology, pathobiology, and advances in diagnosis and control with special reference to India. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 258–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwknegt, C.; van Rijn, P.A.; Schipper, J.J.M.; Hölzel, D.; Boonstra, J.; Nijhof, A.M.; van Rooij, E.M.A.; Jongejan, F. Potential role of ticks as vectors of bluetongue virus. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 52, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistriková, J.; Briestenska, K. Murid herpesvirus 4 (muHV-4, prototype strain mHV-68) as an important model in global research of human oncogenic gammaherpesviruses. Acta Virol. 2020, 64, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.C.L.; Fenton, A.; Pedersen, A.B. Epidemiology and fitness effects of wood mouse herpesvirus in a natural host population. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 2447–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeippen, C.; Javaux, J.; Xiao, X.; Ledecq, M.; Mast, J.; Farnir, F.; Vanderplasschen, A.; Stevenson, P.; Gillet, L. The Major Envelope Glycoprotein of Murid Herpesvirus 4 Promotes Sexual Transmission. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00235-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnická, V.; Kúdelová, M.; Štibrániová, I.; Slovák, M.; Bartíková, P.; Halásová, Z.; Pančík, P.; Belvončíková, P.; Vrbová, M.; Holíková, V.; et al. Tick-Borne Transmission of Murine Gammaherpesvirus 68. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariconti, M.; Obadia, T.; Mousson, L.; Malacrida, A.; Gasperi, G.; Failloux, A.-B.; Yen, P.-S. Estimating the risk of arbovirus transmission in Southern Europe using vector competence data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglietta, M.; Bellone, R.; Blisnick, A.A.; Failloux, A.-B. Vector Specificity of Arbovirus Transmission. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 773211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehse-Küpper, B.; Casals, J.; Rehse, E.; Ackermann, R. Eyach—An arthropod-borne virus related to Colorado tick fever virus in the Federal Republic of Germany. Acta Virol. 1976, 20, 339–342. [Google Scholar]

- Chastel, C.; Main, A.J.; Couatarmanac’h, A.; Le Lay, G.; Knudson, D.L.; Quillien, M.C.; Beaucournu, J.C. Isolation of Eyach virus (Reoviridae, Colorado tick fever group) from Ixodes ricinus and I. ventalloi ticks in France. Arch. Virol. 1984, 82, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, B.N.; Fischer, R.J.; Lopez, J.E.; Ebihara, H.; Schwan, T.G. Prevalence and strains of Colorado tick fever virus in Rocky Mountain wood ticks in the Bitterroot Valley, Montana. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019, 19, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]