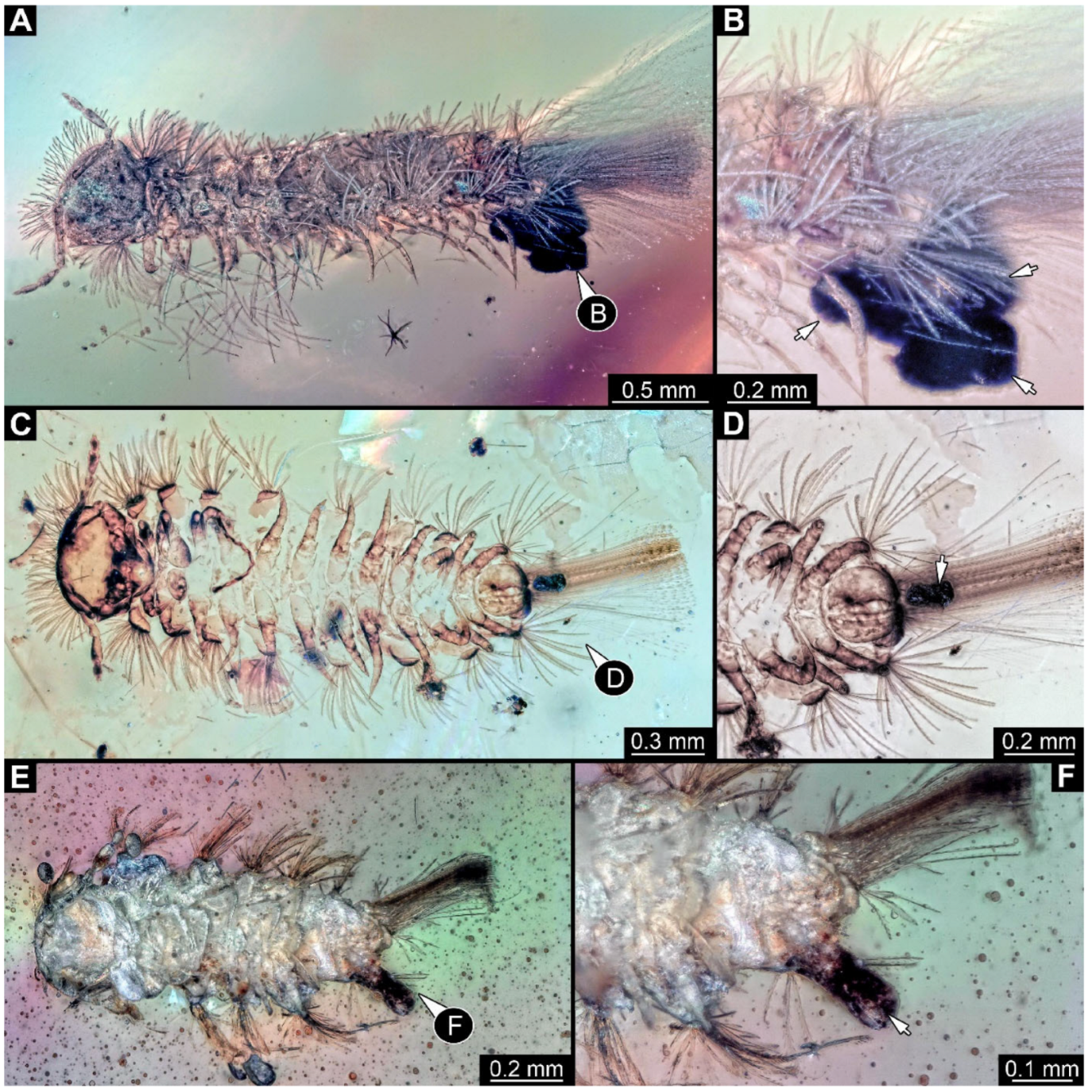

Figure 1.

A 100-million-year-old community of 87 specimens of Synxenidae in Kachin amber (NIGP208860). (

A) Overview of the amber. (

B) Two individuals of Synxenidae with a mite (NIGP208860-92) attached to NIGP208860-27. (

C) Mouthparts of NIGP208860-92. (

D) Five individuals of Synxenidae (NIGP208860-46, 69–71, 83) of different developmental stages with frass close by. (

E) NIGP208860-81; immature of stage 1. (

F) NIGP208860-58, NIGP208860-61, and NIGP208860-62 with frass close by (arrows). (

G) NIGP208860-90–91, in ventral view. Abbreviations: numbers refer to specimen number in this amber piece (see

Supplementary Figure S1); arrows refer to frass.

Figure 1.

A 100-million-year-old community of 87 specimens of Synxenidae in Kachin amber (NIGP208860). (

A) Overview of the amber. (

B) Two individuals of Synxenidae with a mite (NIGP208860-92) attached to NIGP208860-27. (

C) Mouthparts of NIGP208860-92. (

D) Five individuals of Synxenidae (NIGP208860-46, 69–71, 83) of different developmental stages with frass close by. (

E) NIGP208860-81; immature of stage 1. (

F) NIGP208860-58, NIGP208860-61, and NIGP208860-62 with frass close by (arrows). (

G) NIGP208860-90–91, in ventral view. Abbreviations: numbers refer to specimen number in this amber piece (see

Supplementary Figure S1); arrows refer to frass.

Figure 2.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 2596. (B) Close-up view of the frass around the exuvia. (C) Wood bark with frass around. (D) PED 2596-1 in ventral view; unknown developmental stage. Abbreviations: e1–e4 = exuviae 1–4; arrows refer to pieces of frass.

Figure 2.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 2596. (B) Close-up view of the frass around the exuvia. (C) Wood bark with frass around. (D) PED 2596-1 in ventral view; unknown developmental stage. Abbreviations: e1–e4 = exuviae 1–4; arrows refer to pieces of frass.

Figure 3.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae and Polyxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 3238; numbers refer to the specimen number in this amber piece. (B) PED 3238-5 in dorsal view; immature of Polyxenidae of stage 6. (C) PED 3238-8; exuvia of Synxenidae. (D) PED 3238-2 in ventral view; immature of Synxenidae of stage 2. (E) PED 3238-7; fragmented remains of Synxenidae. Abbreviation: e1 = exuvia 1.

Figure 3.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae and Polyxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 3238; numbers refer to the specimen number in this amber piece. (B) PED 3238-5 in dorsal view; immature of Polyxenidae of stage 6. (C) PED 3238-8; exuvia of Synxenidae. (D) PED 3238-2 in ventral view; immature of Synxenidae of stage 2. (E) PED 3238-7; fragmented remains of Synxenidae. Abbreviation: e1 = exuvia 1.

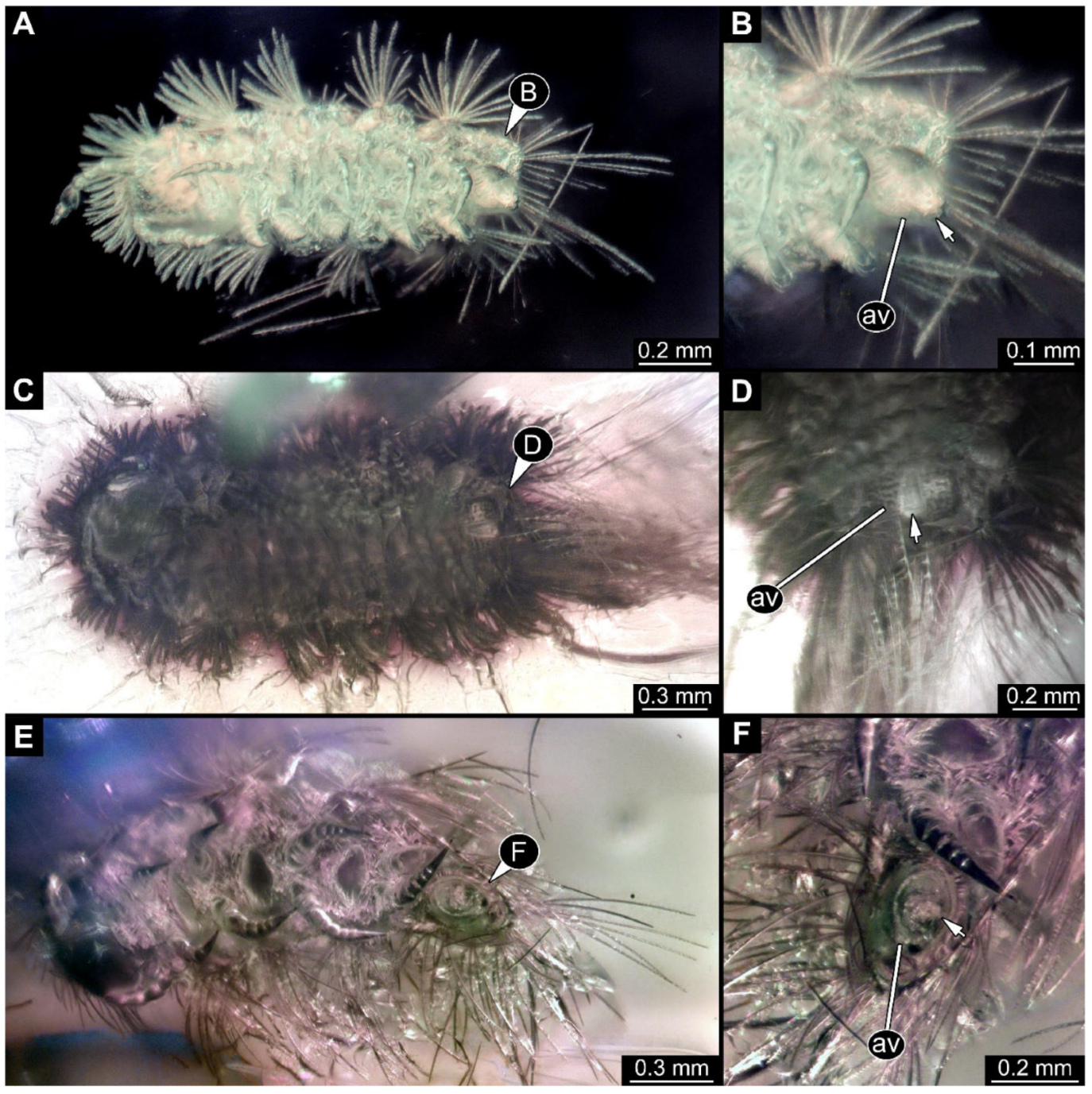

Figure 4.

A 100-million-year-old community of eleven specimens of Synxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 1488; numbers refer to the specimen number in this amber piece. (B) PED 1488-1 in ventral view; immature of stage 5. (C) PED 1488-3 in ventral view; immature of stage 8. (D) PED 1488-11 in ventral view; immature of stage 8. (E) PED 1488-4 in dorsal view; immature of stage 7. (F) PED 1488-5 in lateral view; immature of stage 7. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; te = terminal end; arrows refer to pieces of frass.

Figure 4.

A 100-million-year-old community of eleven specimens of Synxenidae in Kachin amber. (A) Overview of the amber PED 1488; numbers refer to the specimen number in this amber piece. (B) PED 1488-1 in ventral view; immature of stage 5. (C) PED 1488-3 in ventral view; immature of stage 8. (D) PED 1488-11 in ventral view; immature of stage 8. (E) PED 1488-4 in dorsal view; immature of stage 7. (F) PED 1488-5 in lateral view; immature of stage 7. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; te = terminal end; arrows refer to pieces of frass.

Figure 5.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae, preserved in the Kachin amber PED 2755. (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the specimen numbers. (B) PED 2755-5 in lateral view; poorly preserved individual. (C) PED 2755-3 in lateral view; immature with a preserved frass close by (arrow). (D,E) PED 2755-1 terminal end. (D) PED 2755-1 in ventral view; immature of unknown developmental stage. (E) Close-up of the terminal end with a frass (arrow).

Figure 5.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae, preserved in the Kachin amber PED 2755. (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the specimen numbers. (B) PED 2755-5 in lateral view; poorly preserved individual. (C) PED 2755-3 in lateral view; immature with a preserved frass close by (arrow). (D,E) PED 2755-1 terminal end. (D) PED 2755-1 in ventral view; immature of unknown developmental stage. (E) Close-up of the terminal end with a frass (arrow).

Figure 6.

A 100-million-year-old community of ten individuals of Synxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber PED 2885. (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of specimens. (B) PED 2885-2 in ventro-lateral view; immature female of stage 9. (C) Close-up view of PED 2885-2 terminal end with a frass piece (arrow). (D) PED 2885-1 in dorsal view; immature of stage 1–2. (E) PED 2885-6; exuvia of Synxenidae. Abbreviation: vu = vulval sacs.

Figure 6.

A 100-million-year-old community of ten individuals of Synxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber PED 2885. (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of specimens. (B) PED 2885-2 in ventro-lateral view; immature female of stage 9. (C) Close-up view of PED 2885-2 terminal end with a frass piece (arrow). (D) PED 2885-1 in dorsal view; immature of stage 1–2. (E) PED 2885-6; exuvia of Synxenidae. Abbreviation: vu = vulval sacs.

Figure 7.

A 100-million-year-old community of five representatives of Synxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber (PED 3328). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of the specimens. (B) PED 3328-1 in dorsal view; fragmented seemingly immature of at least stage 9. (C) PED 3328-2 in ventral view; immature of seemingly stage 5 with frass in front of the anal valves (arrow). (D) PED 3328-4 in dorsal view; adult female of stage 10 with PED 3328-3 in ventro-lateral view, and immature of unknown stage with frass close by (arrow).

Figure 7.

A 100-million-year-old community of five representatives of Synxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber (PED 3328). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of the specimens. (B) PED 3328-1 in dorsal view; fragmented seemingly immature of at least stage 9. (C) PED 3328-2 in ventral view; immature of seemingly stage 5 with frass in front of the anal valves (arrow). (D) PED 3328-4 in dorsal view; adult female of stage 10 with PED 3328-3 in ventro-lateral view, and immature of unknown stage with frass close by (arrow).

Figure 8.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae, in Kachin amber (PED 2439). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the number of specimens. (B) PED 2439-1 in ventro-lateral view; immature of stage 6 with frass around it (arrow). (C) Close-up of multiple pieces of frass. (D) PED 2439-2 in lateral view; fragmented immature of seemingly stage 6. (E) PED 2439-3 in ventral view; curled specimens of unknown stage.

Figure 8.

A 100-million-year-old community of Synxenidae, in Kachin amber (PED 2439). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the number of specimens. (B) PED 2439-1 in ventro-lateral view; immature of stage 6 with frass around it (arrow). (C) Close-up of multiple pieces of frass. (D) PED 2439-2 in lateral view; fragmented immature of seemingly stage 6. (E) PED 2439-3 in ventral view; curled specimens of unknown stage.

Figure 9.

The different phases of defecation in Synxenidae and Polyxenidae. (A,B) PED 0787, Baltic amber, Synxenidae. (A) Immature of stage 3 in ventral view, with anal valves closed. (B) Close-up of the terminal end. (C,D) PED 0786, Baltic amber, Synxenidae. (C) Immature of stage 4 in ventral view, with anal valves opened and frass within it. (D) Close-up of the terminal end and frass (arrow). (E,F) PED 1430, Kachin amber, Polyxenidae. (E) Immature of at least stage 7 in ventral view, with frass going out. (F) Close-up of the terminal end and frass (arrow). Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 9.

The different phases of defecation in Synxenidae and Polyxenidae. (A,B) PED 0787, Baltic amber, Synxenidae. (A) Immature of stage 3 in ventral view, with anal valves closed. (B) Close-up of the terminal end. (C,D) PED 0786, Baltic amber, Synxenidae. (C) Immature of stage 4 in ventral view, with anal valves opened and frass within it. (D) Close-up of the terminal end and frass (arrow). (E,F) PED 1430, Kachin amber, Polyxenidae. (E) Immature of at least stage 7 in ventral view, with frass going out. (F) Close-up of the terminal end and frass (arrow). Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 10.

Holotype of Polyxenus conformis, from the Berendt Collection in Berlin (MB.A.1606-1). (A) Ventral view of the millipede; adult of stage 8. (B) Close-up view of the frass in front of the anal valves (arrows) of the animal. (C) Dorsal view of the bristly millipede. Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 10.

Holotype of Polyxenus conformis, from the Berendt Collection in Berlin (MB.A.1606-1). (A) Ventral view of the millipede; adult of stage 8. (B) Close-up view of the frass in front of the anal valves (arrows) of the animal. (C) Dorsal view of the bristly millipede. Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 11.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, in Kachin amber; arrows refer to the frass. (A,B) PED 3560, in ventral view. (A) Immature of stage 4. (B) Close-up stereo anaglyph image of defecation. (C,D) PED 3665, in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 4. (D) Close-up stereo anaglyph image of defecation. (E,F) PED 1084, in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 7. (F) Close-up of the frass in front of the anal valves. Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 11.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, in Kachin amber; arrows refer to the frass. (A,B) PED 3560, in ventral view. (A) Immature of stage 4. (B) Close-up stereo anaglyph image of defecation. (C,D) PED 3665, in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 4. (D) Close-up stereo anaglyph image of defecation. (E,F) PED 1084, in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 7. (F) Close-up of the frass in front of the anal valves. Abbreviation: av = anal valves.

Figure 12.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in Kachin amber (PED 2209) with traces of defecation. (A) Overview of the amber piece. (B,C) PED 2209-1. (B) Immature of stage 6 in ventral view. (C) Close-up of the frass in front of the anal valves. (D,E) PED 2209-2. (D) Immature of stage 8 in ventral view. (E) Close-up of the frass, close to the anal valves. Abbreviations: vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to the frass.

Figure 12.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in Kachin amber (PED 2209) with traces of defecation. (A) Overview of the amber piece. (B,C) PED 2209-1. (B) Immature of stage 6 in ventral view. (C) Close-up of the frass in front of the anal valves. (D,E) PED 2209-2. (D) Immature of stage 8 in ventral view. (E) Close-up of the frass, close to the anal valves. Abbreviations: vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to the frass.

Figure 13.

Community of Synxenidae with a pseudoscorpion, syninclusion in Kachin amber (PED 1003). (A) Overview of the amber PED 1003; numbers refer to the number of the specimens. (B) PED 1003-1, potential exuvia with seemingly frass. (C) PED 1003-2, exuvia of Synxenidae. (D) Close-up view of the amber piece with frass pieces. (E) PED 1003-3, seemingly an immature of unknown stage, targeted by PED 1003-4, a pseudoscorpion; black arrows refer to detached defensive setae. (F) Close-up of defensive setae and a piece of frass attached to the body of PED 1003-4. Abbreviations: sc = scale setae; arrows refer to the frass.

Figure 13.

Community of Synxenidae with a pseudoscorpion, syninclusion in Kachin amber (PED 1003). (A) Overview of the amber PED 1003; numbers refer to the number of the specimens. (B) PED 1003-1, potential exuvia with seemingly frass. (C) PED 1003-2, exuvia of Synxenidae. (D) Close-up view of the amber piece with frass pieces. (E) PED 1003-3, seemingly an immature of unknown stage, targeted by PED 1003-4, a pseudoscorpion; black arrows refer to detached defensive setae. (F) Close-up of defensive setae and a piece of frass attached to the body of PED 1003-4. Abbreviations: sc = scale setae; arrows refer to the frass.

Figure 14.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, preserved in Kachin amber. (A) PED 1298 in dorso-lateral view; immature of unclear stage. (B,C) PED 1457-2 in ventro-lateral view. (B) Close-up view on the frass. (C) Immature of stage 6. (D,E) PED 1309 in ventro-lateral view. (D) Immature of stage 9; seemingly female. (E) Close-up view on the frass. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 14.

Fossilized individuals of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, preserved in Kachin amber. (A) PED 1298 in dorso-lateral view; immature of unclear stage. (B,C) PED 1457-2 in ventro-lateral view. (B) Close-up view on the frass. (C) Immature of stage 6. (D,E) PED 1309 in ventro-lateral view. (D) Immature of stage 9; seemingly female. (E) Close-up view on the frass. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 15.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, in Kachin amber. (A) PED 1691 in lateral view, fragmented specimen of unknown stage. (B) PED 1843 in lateral view, immature of stage 4. (C) PED 2061-2 in lateral view, immature of stage 8. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 15.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae in the process of defecation, in Kachin amber. (A) PED 1691 in lateral view, fragmented specimen of unknown stage. (B) PED 1843 in lateral view, immature of stage 4. (C) PED 2061-2 in lateral view, immature of stage 8. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 16.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae, preserved while defecating in Kachin amber. (A,B) PED 0863 in ventral view. (A) Adult female with frass in front of its anal valves. (B) Close-up view of the frass. (C) PED 0591 in ventro-lateral view, immature female of stage 8. (D,E) BUB 4991 in ventral view. (D) Fragmented immature female of seemingly stage 9. (E) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviation: vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 16.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae, preserved while defecating in Kachin amber. (A,B) PED 0863 in ventral view. (A) Adult female with frass in front of its anal valves. (B) Close-up view of the frass. (C) PED 0591 in ventro-lateral view, immature female of stage 8. (D,E) BUB 4991 in ventral view. (D) Fragmented immature female of seemingly stage 9. (E) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviation: vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 17.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae, preserved while defecating in Kachin amber. (A,B) PED 1598-2 in ventral view. (A) Immature female of stage 7. (B) Close-up view of the frass. (C,D) PED 1570 in ventral view. (C) Adult female of stage 10. (D) Close-up view of the frass. (E,F) PED 3468 in ventro-lateral view. (E) Immature of stage 9. (F) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 17.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae, preserved while defecating in Kachin amber. (A,B) PED 1598-2 in ventral view. (A) Immature female of stage 7. (B) Close-up view of the frass. (C,D) PED 1570 in ventral view. (C) Adult female of stage 10. (D) Close-up view of the frass. (E,F) PED 3468 in ventro-lateral view. (E) Immature of stage 9. (F) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 18.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae preserved in Eocene ambers, in the process of defecation. (A) PED 0056 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, immature of stage 1. (B) PED 0035 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, immature of stage 2. (C) GPIH Scheele 1362 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, adult female of stage 10. (D) GPIH Nielsen AKBS-01419 (Baltic amber) in ventro-lateral view, immature of stage 3. (E,F) Bi0586 (Bitterfeld amber) in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 1. (F) Close-up stereoscopic image the terminal end. Abbreviations: av? = possible anal valves; vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 18.

Fossilized representatives of Synxenidae preserved in Eocene ambers, in the process of defecation. (A) PED 0056 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, immature of stage 1. (B) PED 0035 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, immature of stage 2. (C) GPIH Scheele 1362 (Baltic amber) in ventral view, adult female of stage 10. (D) GPIH Nielsen AKBS-01419 (Baltic amber) in ventro-lateral view, immature of stage 3. (E,F) Bi0586 (Bitterfeld amber) in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 1. (F) Close-up stereoscopic image the terminal end. Abbreviations: av? = possible anal valves; vu = vulval sacs; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 19.

A 100-million-year-old community of Polyxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber (PED 4057). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of specimens. (B) Close-up view of multiple pieces of frass. (C) PED 4057-2, exuvia of Polyxenidae. (D) PED 4057-1 in ventral view, immature of stage 6. (E,F) PED 4057-3 in ventral view. (E) Immature of seemingly stage 7 with frass in front of the anal valves. (F) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 19.

A 100-million-year-old community of Polyxenidae, preserved in Kachin amber (PED 4057). (A) Overview of the amber piece; numbers refer to the numbers of specimens. (B) Close-up view of multiple pieces of frass. (C) PED 4057-2, exuvia of Polyxenidae. (D) PED 4057-1 in ventral view, immature of stage 6. (E,F) PED 4057-3 in ventral view. (E) Immature of seemingly stage 7 with frass in front of the anal valves. (F) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 20.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenidae found defecating, in Kachin amber. (A) PED 0429 in dorsal view, fragmented immature of at least stage 7. (B) PED 0860 in ventral view, immature of stage 6. (C,D) PED 1685 in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 7. (D) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 20.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenidae found defecating, in Kachin amber. (A) PED 0429 in dorsal view, fragmented immature of at least stage 7. (B) PED 0860 in ventral view, immature of stage 6. (C,D) PED 1685 in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 7. (D) Close-up view of the frass. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 21.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenidae found defecating. (A,B) PED 0285 in Baltic amber, in ventro-lateral view. (A) Immature of stage 7 with multiple frass. (B) Close-up view on the terminal end. (C,D) PED 0697 in Kachin amber, in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 7 with one detached frass. (D) Close-up view on the terminal end. (E,F) PED 0947 in Kachin amber, in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 4 with frass coming out. (F) Close-up on the terminal end of PED 0947. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 21.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenidae found defecating. (A,B) PED 0285 in Baltic amber, in ventro-lateral view. (A) Immature of stage 7 with multiple frass. (B) Close-up view on the terminal end. (C,D) PED 0697 in Kachin amber, in ventral view. (C) Immature of stage 7 with one detached frass. (D) Close-up view on the terminal end. (E,F) PED 0947 in Kachin amber, in ventral view. (E) Immature of stage 4 with frass coming out. (F) Close-up on the terminal end of PED 0947. Abbreviation: arrows refer to frass.

Figure 22.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenida found in the process of defecation. (A,B) SMF Be 628b in Chiapas amber, in ventro-lateral view. (A) Immature of stage 3 with protruding anal valves. (B) Close-up view of the terminal end. (C,D) MB.A.0537 in Baltic amber, in ventral view. (C) Adult of Polyxenidae from stage 8, identified as Polyxenus sp. Latzel, 1884, with opened anal valves and frass visible. (D) Close-up view of the terminal end. (E,F) MB.A.0539 in Baltic amber, in ventral view. (E) Immature of Synxenidae from stage 2, with frass going out from the anal valves. (F) Close-up view of the terminal end. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 22.

Fossilized representatives of Polyxenida found in the process of defecation. (A,B) SMF Be 628b in Chiapas amber, in ventro-lateral view. (A) Immature of stage 3 with protruding anal valves. (B) Close-up view of the terminal end. (C,D) MB.A.0537 in Baltic amber, in ventral view. (C) Adult of Polyxenidae from stage 8, identified as Polyxenus sp. Latzel, 1884, with opened anal valves and frass visible. (D) Close-up view of the terminal end. (E,F) MB.A.0539 in Baltic amber, in ventral view. (E) Immature of Synxenidae from stage 2, with frass going out from the anal valves. (F) Close-up view of the terminal end. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; arrows refer to frass.

Figure 23.

Extant representatives of Polyxenida, mounted permanently on slides or stored in ethanol in the Zoological State Collection Munich; arrows refer to the frass. (A) Phryssonotus novaehollandiae in ventral view, immature of stage 5 in the process of defecating. (B) Polyxenus lagurus in ventral view, adult of stage 8 with frass pushed through the anal valves. (C–F) Representatives of Lophoproctus. (C) Fragmented seemingly adult in lateral view with frass pushed through the anal valves. (D) Immature of stage 5 in ventral view in the process of defecating. (E) Close-up view of the frass pushed through the anal valves. (F) Seemingly prolapsed digestive tracks, in lateral view, sticking out of the anal valves. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; dt? = possible digestive tracks.

Figure 23.

Extant representatives of Polyxenida, mounted permanently on slides or stored in ethanol in the Zoological State Collection Munich; arrows refer to the frass. (A) Phryssonotus novaehollandiae in ventral view, immature of stage 5 in the process of defecating. (B) Polyxenus lagurus in ventral view, adult of stage 8 with frass pushed through the anal valves. (C–F) Representatives of Lophoproctus. (C) Fragmented seemingly adult in lateral view with frass pushed through the anal valves. (D) Immature of stage 5 in ventral view in the process of defecating. (E) Close-up view of the frass pushed through the anal valves. (F) Seemingly prolapsed digestive tracks, in lateral view, sticking out of the anal valves. Abbreviations: av = anal valves; dt? = possible digestive tracks.

Table 1.

Number of individuals per developmental stage in NIGP208860 (unsure stages are included in brackets).

Table 1.

Number of individuals per developmental stage in NIGP208860 (unsure stages are included in brackets).

| nind (Unsure) | Stage |

|---|

| 4 (2) | 1 |

| 6 (1) | 2 |

| 8 (2) | 3 |

| 9 (4) | 4 |

| 11 (5) | 5 |

| 4 (2) | 6 |

| 4 | 7 |

| 4 (2) | 8 |

| (1) | 9 |

| 0 | 10 |

| 18 | not identifiable |

Table 2.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 3238, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

Table 2.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 3238, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 3238-1 | 3? | Yes |

| PED 3238-2 | 2 | - |

| PED 3238-3 | 6 | - |

| PED 3238-4 | 2 | - |

| PED 3238-5 | 6 | - |

| PED 3238-6 | - | - |

| PED 3238-7 | - | - |

| PED 3238-8 | exuvia | - |

| PED 3238-9 | 5? | - |

| PED 3238-10 | 6? | Yes |

| PED 3238-11 | 4 | - |

| PED 3238-12 | 5 | Yes |

Table 3.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 1488, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

Table 3.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 1488, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 1488-1 | 5 | Yes? |

| PED 1488-2 | - | - |

| PED 1488-3 | 8 | Yes |

| PED 1488-4 | 7 | Yes? |

| PED 1488-5 | 7 | Yes? |

| PED 1488-6 | unclear | - |

| PED 1488-7 | unclear | - |

| PED 1488-8 | 8? | - |

| PED 1488-9 | 7 | - |

| PED 1488-10 | unclear | - |

| PED 1488-11 | 8 | Yes? |

Table 4.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2755, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

Table 4.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2755, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 2755-1 | unclear | Yes |

| PED 2755-2 | - | - |

| PED 2755-3 | unclear | Yes? |

| PED 2755-4 | 3 | - |

| PED 2755-5 | unclear | - |

| PED 2755-6 | exuvia | - |

| PED 2755-7 | unclear | - |

Table 5.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2885, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

Table 5.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2885, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 2885-1 | 1–2? | - |

| PED 2885-2 | unclear | - |

| PED 2885-3 | - | - |

| PED 2885-4 | 4 | - |

| PED 2885-5 | exuvia | - |

| PED 2885-6 | exuvia | - |

| PED 2885-7 | 9 | Yes |

| PED 2885-8 | 9? | - |

| PED 2885-9 | unclear | - |

| PED 2885-10 | - | - |

Table 6.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 3328, including the ones defecating.

Table 6.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 3328, including the ones defecating.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 3328-1 | - | - |

| PED 3328-2 | 3 | Yes |

| PED 3328-3 | unclear | Yes |

| PED 3328-4 | 10 | - |

| PED 3328-5 | unclear | - |

Table 7.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2439, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

Table 7.

Information on the developmental stage of bristly millipedes in PED 2439, including the ones defecating. Abbreviation: (?) refers to unclear finds.

| Ind# | Stage | Defecation |

|---|

| PED 2439-1 | 6 | Yes? |

| PED 2439-2 | 7? | - |

| PED 2439-3 | unclear | Yes? |

| PED 2439-4 | 10? | - |