Exploring the Perception of Additional Information Content in 360° 3D VR Video for Teaching and Learning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Previous Research

- Immersion and presence—a sense of “being” within an environment has been highlighted as particularly important for spatial learning [19], whilst exploration of the content at the learner’s own pace facilitates a constructivist approach to learning.

- Comfort—discomfort has been associated with learner disengagement [25]. VR delivered by HMDs is often associated with motion sickness (often termed cybersickness in this context [26]). VR content can be designed to mitigate this risk, such as allowing the user to control all movement [27] to reduce sensory disconnect.

3. Materials and Methods

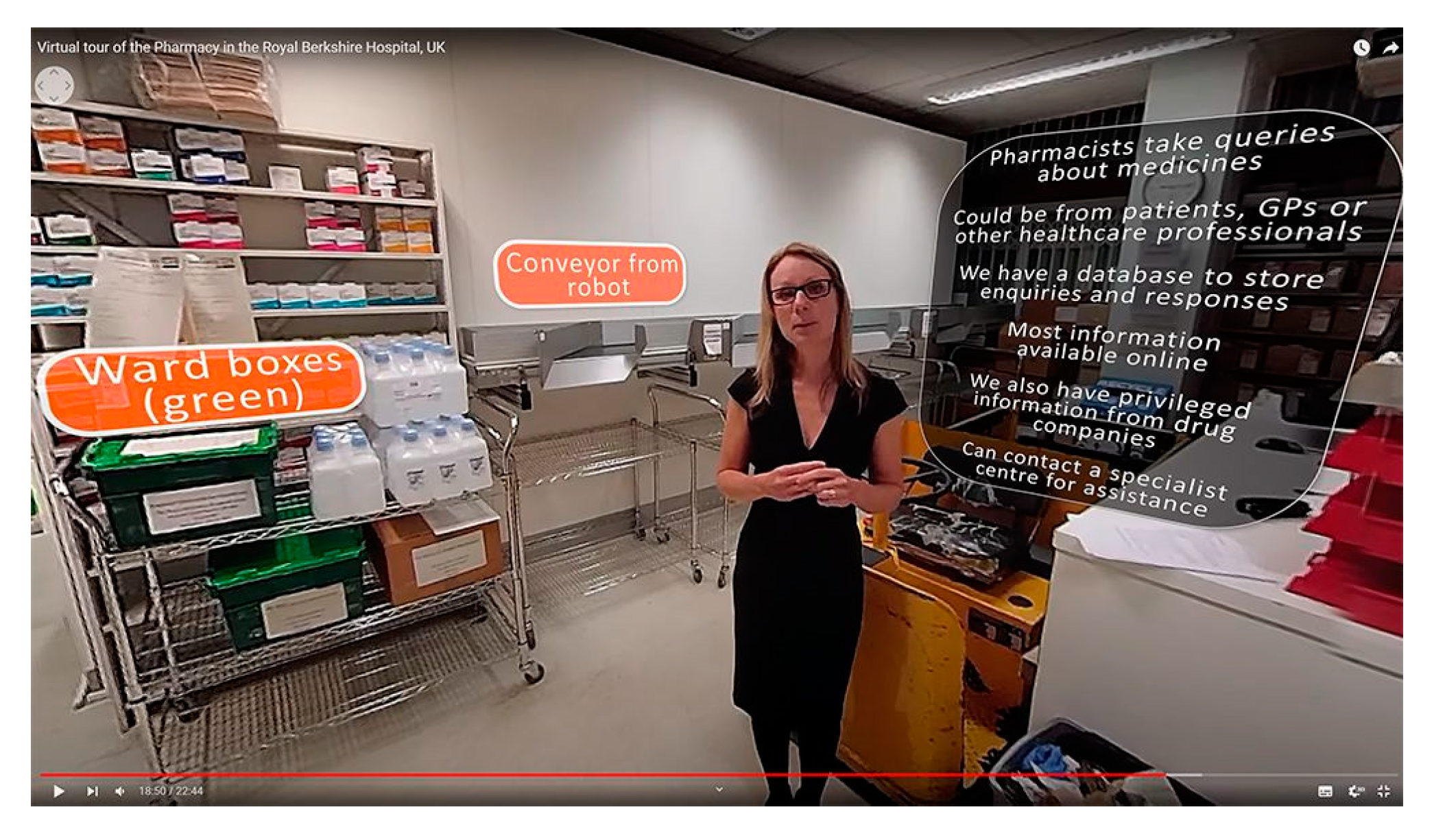

- 13 labels highlighting the name of the functional spaces within the pharmacy (one per space presented at the start of each new location; white text on a black background)

- 41 labels for key objects or areas within the video (2–7 on-screen simultaneously; white text with an orange background)

- 23 summary text boxes adjacent to the presenter summarising the spoken content (one on-screen at any time; white text on a black background)

3.1. Participants

3.2. Study Design

3.3. Thematic Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Interaction with the Virtual “Real” Environment

4.1.1. Exploration of Content in the Virtual “Real” Environment

“Curiosity, to see what everything was there just to get all of it in. It’s not usual where you get to see a film, you just get to have a look around and see the rest of the scenery as well but yeah its interesting being able to see everything in the room as opposed to what’s right in front of you.”

“Usually when you’re here in person, you expect it to be like looking at the person talking and to show you are actually listening to, but I didn’t feel that need there and I just listened to what happened and I was looking at all the things around me.”

“Looking around gave me a better idea of what it would be like to work in person.”

“I was so distracted by the fact I could look around and explore that I didn’t necessarily take in the information. I was aware she was talking, and I was trying to pay attention but then I was like, oh, what’s that over there?”

4.1.2. Learning in the Virtual “Real” Environment

“So I think it does definitely have sort of those advantages to VR so you can see more almost you can go back and review it, you can take your time with it”“The issue with going in person is that you don’t get to do it again if you forget something.”

“I think it was better because if you are in a big group you aren’t standing behind someone, you aren’t trying to listen to someone and its focussed on you, that’s a positive for the VR.“

“I think one downside of the VR headset is I couldn’t take notes, so I wouldn’t have been able to recall that information.“

“You wouldn’t be able to ask questions in a VR environment.”

“…if there was maybe a short quiz after each clip or like if you had maybe split it into two or something then that might work as well.“

4.2. Interaction with the Virtual “Augmented” Environment

4.2.1. Labelling

“I think it would have been very useful to have little labels pop up as things were being explained to explain which segments she was referring to.”“If you could see labels above different doors to other places that would potentially help there. So I think labels and the text would certainly be useful, absolutely.”“Smaller rooms its not that hard to figure out where she is pointing but then the largest rooms that might actually yeah be helpful.”

“There were the orange text markers, so I was looking around to see if there were any of those in the clip anywhere other than straight forward.”

“Sometimes I got distracted from what she was talking about and focused on reading”(Group B participant)

4.2.2. Summary Text

“I liked the pop-ups which summarised what she was saying, I thought they were really good and because they covered sort of the really important parts of what she was saying.”

“I don’t think I took in everything that [presenter] said but from the summaries that kept popping up I think that I got all of that information.”

“The orange ones were easier, I think they were shorter as well.”

“So asking about whose role was what, I struggled a bit more with and again perhaps that’s because I have less familiarity with the area but perhaps not if this is intended for students who are coming in kind of a baseline as well, then I think understanding which role applied to which room and which scenario. Maybe that could have been, you know, better signposted visually maybe with text.”

4.2.3. Request for Incorporation of Augmentation Features

“You’re kind of teleported there, so perhaps a video of just someone walking through those spaces at the beginning, or an embedded video or even a floor plan might be something that can help you picture where you are.”

4.2.4. Learning in the Virtual “Augmented” Environment

“If it were one on one I don’t think from the information delivered so much it would be much different. You would lose the summaries which I found really valuable because they gave you the really important information, so I think that would be a loss. However, an in person conversation you can do dialogue so if there is a query or you have something you don’t understand, you can ask and she will explain it better, which is something you can’t get using videos. But if the opportunity of questions weren’t there and she was just delivering the same talk, but I were in the same room rather than watching on VR, I think VR is better because of the popups in the summaries.”

“I think I liked having the little pop-ups on screen, that gave you a little more information, I think they were good. There might have been a case where one stayed on screen for a bit of time and I found myself reading that instead of listening.“

“I need to read something two to three times for it to solidify in my head”

4.2.5. Exploration of Content in the Virtual “Augmented” Environment

“I wanted to look around and see the space.”“It’s interesting being able to see everything in the room as opposed to what’s right in front of you.”

“There was one where there’s the patient bed, but then it became clear when she spoke why the medicine cabinet next to it was labelled, because she referenced that in terms of that’s where you keep the patient’s own medicine.”

4.3. Usability

4.3.1. Video Length

“I thought it was too long, I wasn’t able to focus for the length of the video.”

“It could work well if there were a break in the middle to just give yourself a bit of a break and acknowledge that you feel that discomfort and that its ok to pause the video and have that break.”

“I think it was a little bit too long, but that might have just been again because I was a bit uncomfortable towards the end, maybe a bit of motion sickness and by the end I wanted to take the headset off.”

4.3.2. Comfort and Discomfort

“So that specific headset was very comfortable inside.”

“it’s obviously quite bulky and a little bit heavy.”

“If I have head bobbing on in a video game, this will cause me motion sickness. I found a similar experience if I moved my head too quickly. If I sat still it wasn’t too bad but if I move my head too quickly to the right or left I would get a bit of motion sickness or disorientation.”“I think worst part was the quality of the video. My eyes get really tired after a while.““…it’s a bit uncomfortable with glasses on…”

4.3.3. Experience of Headset Use

“I found that it was very intuitive with the controller, like to point and click.”

“Initially it was a bit difficult but within a few minutes, I understand how to use it easily now...”

“You know, just hold the button down to sort of bring up the menu and then from there it’s just like using, I don’t know, say another games console or controller of some kind.”

“It took time to get it like it actually fitted…”

4.3.4. Factors Affecting Enjoyment

“I quite liked the novelty of it at least and I quite liked the different format and I found it quite fascinating, actually being able to look at it from a 360 degree point of view.”“I had fun and it was something new to try.”

“It was immersive, I was interested in finding out what was happening in the video but some of the discomfort elements were negative.”

“The video quality wasn’t perfect, it was pixelated, so it didn’t feel like I was completely in but it was still enough that I was able to see what the room was like.”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Labelling may lead to additional exploration and 3D awareness by the learner and incorporation can help direct the learner’s attention to notable features. Where 3D spatial awareness is a key learning outcome, the incorporation of labelling may then assist the learner.

- Summary text may be useful to learners, particularly where text overlaps with information provided orally. This may allow learners to select which cognitive stream they prefer to use to learn, helping the learner to focus.

- The principle of segmentation within the framework for cognitive learning should be applied to 360° 3D VR video to reduce cognitive overload and maximise user comfort. Participants in this study suggested 10 min as the optimal length of the experience. Elements to evaluate student learning could be included between segments for learner self-evaluation outside of the VR environment.

- Video-based experiences should be recorded to maximize fidelity. This may increase both enjoyment and immersion, whereas low fidelity contributes to feelings of discomfort and a reduction in enjoyment.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelly, K.; Heilbrun, A.; Stacks, B. Virtual reality: An interview with jaron lanier. Whole Earth Rev. 1989, 64, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, W.; Bricken, W. Designing virtual worlds for use in mathematics education: The example of experiential algebra. Educ. Technol. 1992, 32, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zeltzer, D. Autonomy, interaction, and presence. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1992, 1, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Wuensche, B.; Plimmer, B. A systematic review of virtual reality in education. Themes Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Horlick, K. Virtual Reality Helps Simulation Team Tackle COVID-19. Available online: https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/news/virtual-reality-helps-simulation-team-tackle-covid19--8664 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Hills-Duty, R. Thames Water Turns To VR To Reduce Work Stress—GMW3. Available online: https://www.gmw3.com/2018/05/thames-water-turns-to-vr-to-reduce-work-stress/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Pulijala, Y.; Ma, M.; Pears, M.; Peebles, D.; Ayoub, A. An innovative virtual reality training tool for orthognathic surgery. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carruth, D.W. Virtual reality for education and workforce training. In Proceedings of the 2017 15th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 26–27 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stupar-Rutenfrans, S.; Ketelaars, L.E.H.; van Gisbergen, M.S. Beat the fear of public speaking: Mobile 360° video virtual reality exposure training in home environment reduces public speaking anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhyaru, J.S.; Kemp, C. Virtual reality as a tool to promote wellbeing in the workplace. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762210844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Yoon, Y.-J.; Song, O.-Y.; Choi, S.-M. Interactive and immersive learning using 360° virtual reality contents on mobile platforms. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, F.; Helms, N.H.; Frandsen, U.P.; Rafn, A.V. Learning effectiveness of 360° video: Experiences from a controlled experiment in healthcare education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, R.; Green, H. Virtual reality for teaching and learning in crime scene investigation. Sci. Justice 2020, 60, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC AR and VR in Learning and Teaching. Available online: https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/7555/1/ar-vr-survey-report-2019.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Pappa, D.; Dunwell, I.; Protopsaltis, A.; Pannese, L.; Hetzner, S.; de Freitas, S.; Rebolledo-Mendez, G. Game-based learning for knowledge sharing and transfer. In Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games; Felicia, P., Ed.; Advances in Game-Based Learning; IGI Global: Portland, OR, USA, 2011; pp. 974–1003. ISBN 9781609604950. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hattingh, H.L.; Robinson, D.; Kelly, A. Evaluation of a simulation-based hospital pharmacy training package for pharmacy students. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lucas, C.; Williams, K.; Bajorek, B. Virtual Pharmacy programs to prepare pharmacy students for community and hospital placements. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, K.A.; Oiknine, A.H.; Files, B.T.; Sinatra, A.M.; Patton, D.; Ericson, M.; Thomas, J.; Khooshabeh, P. Level of immersion affects spatial learning in virtual environments: Results of a three-condition within-subjects study with long intersession intervals. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.M.; Kavanagh, D.O.; Wright Ballester, G.; Wright Ballester, A.; Dicker, P.; Traynor, O.; Hill, A.; Tierney, S. 360° operative videos: A randomised cross-over study evaluating attentiveness and information retention. J. Surg. Educ. 2018, 75, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, D.T.; Chalk, C.; Funnell, W.R.J.; Daniel, S.J. Can virtual reality improve anatomy education? A randomised controlled study of a computer-generated three-dimensional anatomical ear model. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelov, V.; Petkov, E.; Shipkovenski, G.; Kalushkov, T. Modern virtual reality headsets. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Ankara, Turkey, 26–28 June 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, P.; Zarraonandía, T.; Sánchez-Francisco, M.; Aedo, I.; Onorati, T. Do low cost virtual reality devices support learning acquisition? In Proceedings of the XX International Conference on Human Computer Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 25–28 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Siddig, A.; Ragano, A.; Jahromi, H.Z.; Hines, A. Fusion confusion. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Workshop on Immersive Mixed and Virtual Environment Systems—MMVE ’19, New York, NY, USA, 18 June 2019; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman, J.; Sjörs, A.; Lindström, J.; Ledin, T.; Falkmer, T. Performance and autonomic responses during motion sickness. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2009, 51, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebenitsch, L.; Owen, C. Review on cybersickness in applications and visual displays. Virtual Real. 2016, 20, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanney, K.M.; Hash, P. Locus of user-initiated control in virtual environments: Influences on cybersickness. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1998, 7, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velev, D.; Zlateva, P. Virtual reality challenges in education and training. Int. J. Learn. Teach. 2017, 3, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, B. Digital literacy in UK health education: What can be learnt from international research? Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P.; Dionisio, D.; Nisi, V.; Nunes, N. Visually induced motion sickness in 360° videos: Comparing and combining visual optimization techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Munich, Germany, 16–20 October 2018; pp. 244–249. [Google Scholar]

- Snelson, C.; Hsu, Y.-C. Educational 360-degree videos in virtual reality: A scoping review of the emerging research. TechTrends 2020, 64, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Sergueeva, K.; Catangui, M.; Kandaurova, M. Assessing google cardboard virtual reality as a content delivery system in business classrooms. J. Educ. Bus. 2017, 92, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgunsöz, E.; Yildirim, G.; Yildirim, S. The effect of virtual reality on EFL writing performance. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2018, 14, 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, N.; Driver, P. Developing reflective trainee teacher practice with 360-degree video. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 78, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, H.; Fırat, M.; Yüzer, T.V. Trends of video use in distance education: A research synthesis. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 2017, 7, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranieri, M.; Bruni, I.; Luzzi, D. Introducing 360-degree video in higher education: An overview of the literature. In Proceedings of the EDEN Conference Proceedings, Timisoara, Romania, 22–24 June 2020; pp. 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E.; Heiser, J.; Lonn, S. Cognitive Constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Fiorella, L. Principles for Reducing extraneous processing in multimedia learning: Coherence, signaling, redundancy, spatial contiguity, and temporal contiguity principles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Mayer, R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 279–315. [Google Scholar]

- Violante, M.G.; Vezzetti, E.; Piazzolla, P. Interactive virtual technologies in engineering education: Why not 360° videos? Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.; Ross, D. Learning style awareness: A basis for developing teaching and learning strategies. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2001, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowsky, B.A.; Calhoun, B.M.; Tallal, P. Matching learning style to instructional method: Effects on comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mat Halif, M.; Hassan, N.; Sumardi, N.A.; Shekh Omar, A.; Ali, S.; Abdul Aziz, R.; Abdul Majid, A.; Salleh, N.F. Moderating effects of student motivation on the relationship between learning styles and student engagement. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2020, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.W. Qualitative interview design: A practical guide for novice investigators. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative evaluation checklist. Eval. Checklists Proj. 2003, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, A.; Cox, A.L. Questionnaires, in-depth interviews and focus groups. In Research Methods for Human Computer Interaction; Cairns, P., Cox, A.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argyriou, L.; Economou, D.; Bouki, V. Design methodology for 360° immersive video applications: The case study of a cultural heritage virtual tour. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 24, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geri, N.; Winer, A.; Zaks, B. Challenging the six-minute myth of online video lectures: Can interactivity expand the attention span of learners? Online J. Appl. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 5, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.P.; Allman, S.A. Blending virtual reality with traditional approaches to encourage engagement with core chemistry concepts relevant to an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prithul, A.; Adhanom, I.B.; Folmer, E. Teleportation in virtual reality: A mini-review. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai Chin, W.; Ahmad Jaafar Wan Yahaya, W.; Muniandy, B. Virtual science laboratory (Vislab): The effect of visual signalling principles towards students’ perceived motivation. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, T.; Nóbrega, R.; Rodrigues, R.; Pinheiro, M. Dynamic annotations on an interactive web-based 360° video player. In Proceedings of the 23rd International ACM Conference on 3D Web Technology, New York, NY, USA, 20 June 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Litleskare, S.; Calogiuri, G. Camera stabilization in 360° videos and its impact on cyber sickness, environmental perceptions, and psychophysiological responses to a simulated nature walk: A single-blinded randomized trial. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, A.; Turner, J.; Patterson, J.; Schmitz, A.; Armstrong, M.; Glancy, M. Subtitles in 360-degree video. In Proceedings of the Adjunct Publication of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, New York, NY, USA, 14 June 2017; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Agulló, B.; Montagud, M.; Fraile, I. Making interaction with virtual reality accessible: Rendering and guiding methods for subtitles. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2019, 33, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoßfeld, T.; Schatz, R.; Biersack, E.; Plissonneau, L. Internet video delivery in youtube: From traffic measurements to quality of experience. In Data Traffic Monitoring and Analysis: From Measurement, Classification, and Anomaly Detection to Quality of Experience; Biersack, E., Callegari, C., Matijasevic, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 264–301. ISBN 978-3-642-36784-7. [Google Scholar]

| Theme & Definition | Sub-theme & Definition |

|---|---|

| Interaction with the virtual “real” environment | Exploration of content in the virtual real environment |

| Perceptions around the experience and learning related to the simulated environment with no additional augmentation; i.e., the virtual representation of the environment as it would be in the real world | Factors affecting the extent to which learners explore the virtual real environment within the experience |

| Learning in the virtual real environment | |

| Perceptions around learning in the virtual real environment | |

| Interaction with the virtual “augmented” environment | Labelling |

| Perceptions around the experience of learning and content within a simulated real environment which has then been augmented with elements not found within the real environment; in this case text, labels and sounds | Perceptions of usefulness and optimal placement of labels within the virtual augmented environment |

| Summary text | |

| Perceptions of usefulness and optimal placement of summary text within the virtual augmented environment | |

| Learning in the virtual augmented environment | |

| Perceptions around learning in the virtual augmented environment | |

| Exploration of content in the virtual augmented environment | |

| Factors affecting the extent to which learners explore the virtual augmented environment within the experience | |

| Adding augmentation features | |

| Requests to add features which would not have been possible in a real-life environment | |

| Usability | Comfort and discomfort |

| Physical factors which affect the learning experience related to the physical learning environment and delivery method | Factors influencing learner comfort and discomfort during the experience |

| Factors affecting enjoyment | |

| Physical elements which positively or negatively affect the enjoyment of the experience by the learner | |

| Experience of headset use | |

| Perceptions of the overall experience of using the headset, such as ease of use | |

| Video length | |

| Perceived parity or disparity between the actual video length and that viewed as ideal by learners |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allman, S.A.; Cordy, J.; Hall, J.P.; Kleanthous, V.; Lander, E.R. Exploring the Perception of Additional Information Content in 360° 3D VR Video for Teaching and Learning. Virtual Worlds 2022, 1, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds1010001

Allman SA, Cordy J, Hall JP, Kleanthous V, Lander ER. Exploring the Perception of Additional Information Content in 360° 3D VR Video for Teaching and Learning. Virtual Worlds. 2022; 1(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds1010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllman, Sarah A., Joanna Cordy, James P. Hall, Victoria Kleanthous, and Elizabeth R. Lander. 2022. "Exploring the Perception of Additional Information Content in 360° 3D VR Video for Teaching and Learning" Virtual Worlds 1, no. 1: 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds1010001

APA StyleAllman, S. A., Cordy, J., Hall, J. P., Kleanthous, V., & Lander, E. R. (2022). Exploring the Perception of Additional Information Content in 360° 3D VR Video for Teaching and Learning. Virtual Worlds, 1(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds1010001