Black Box Warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration: The Impact on the Dispensing Rate of Benzodiazepines

Abstract

1. Introduction

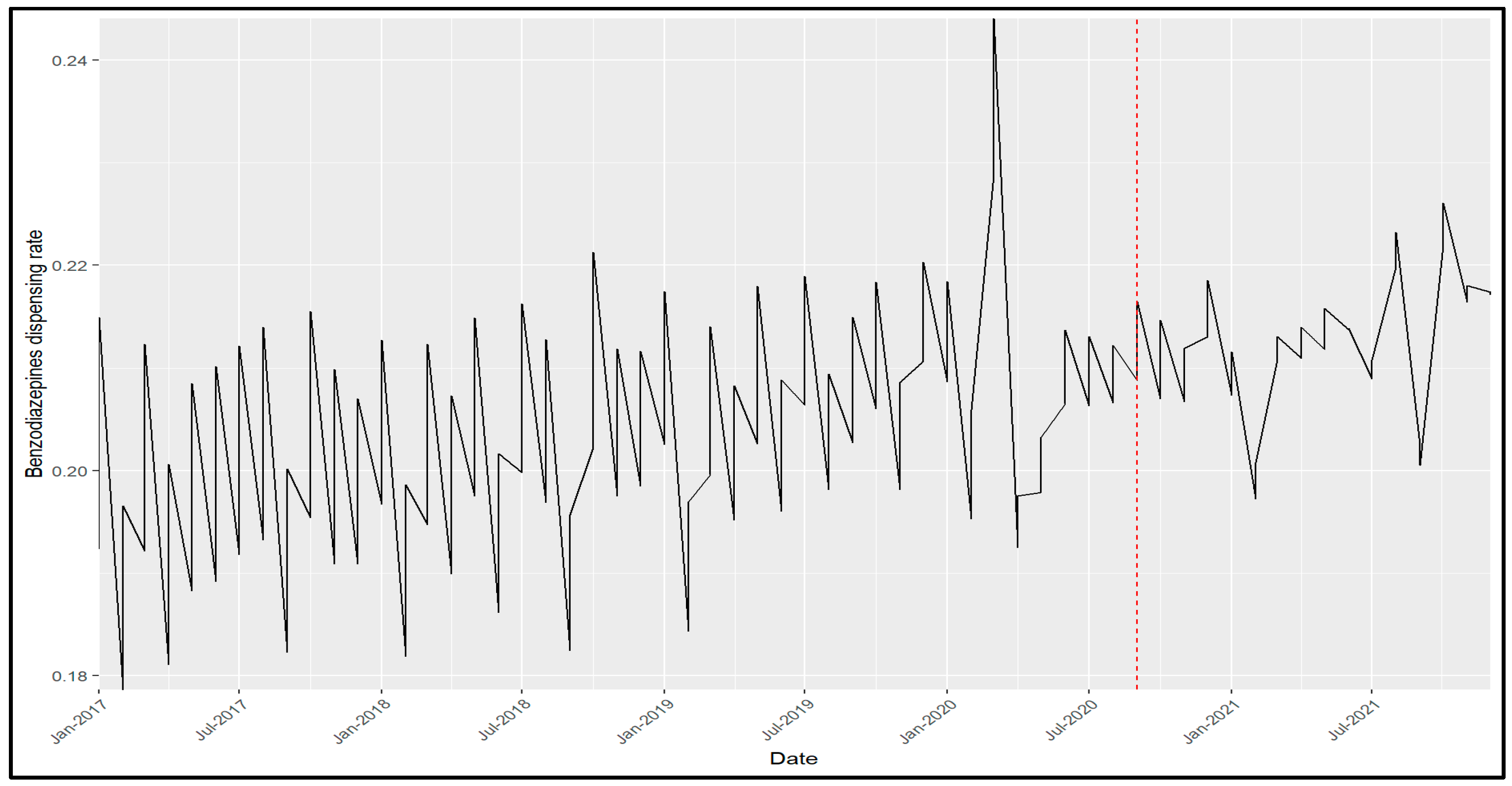

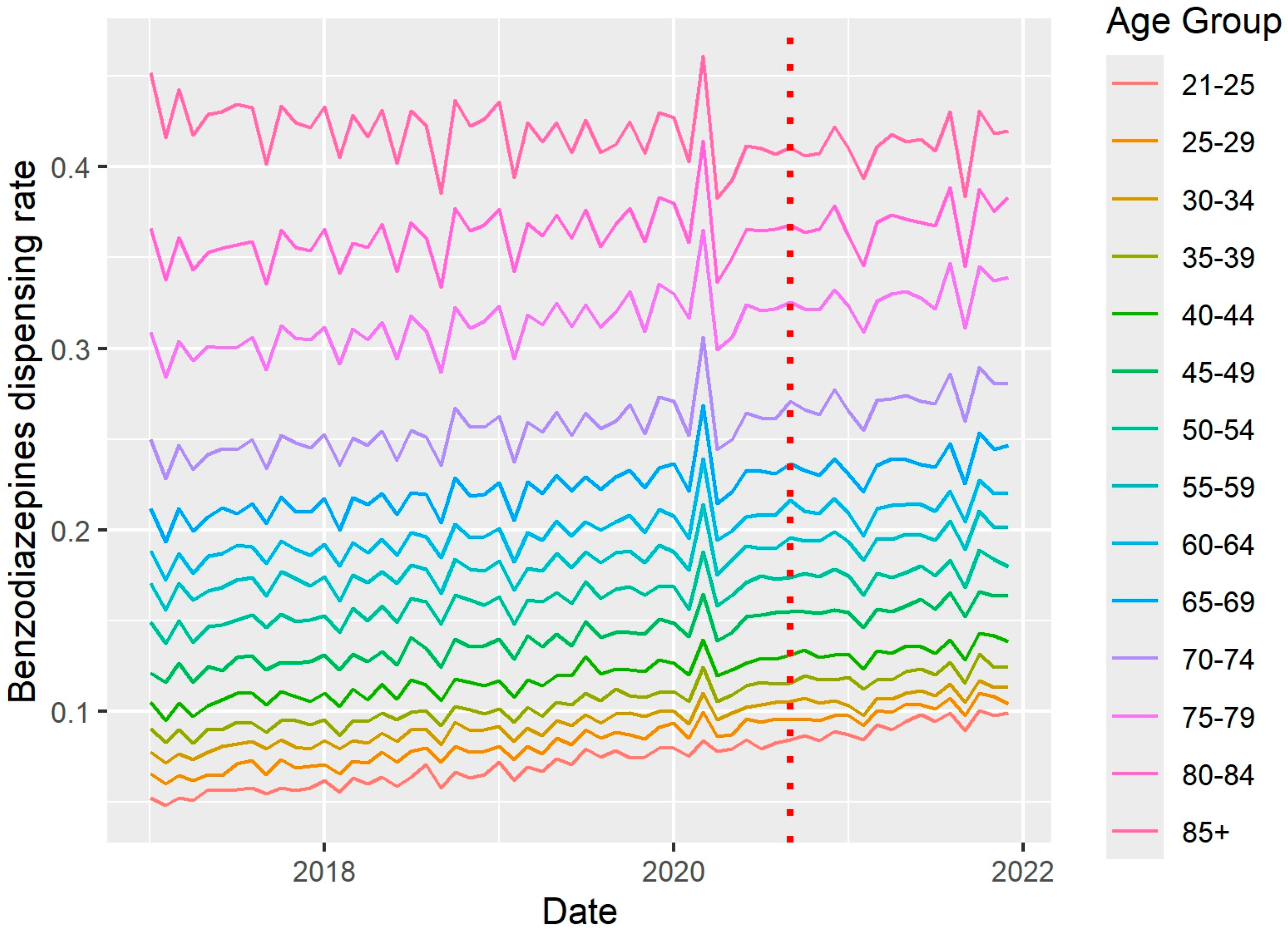

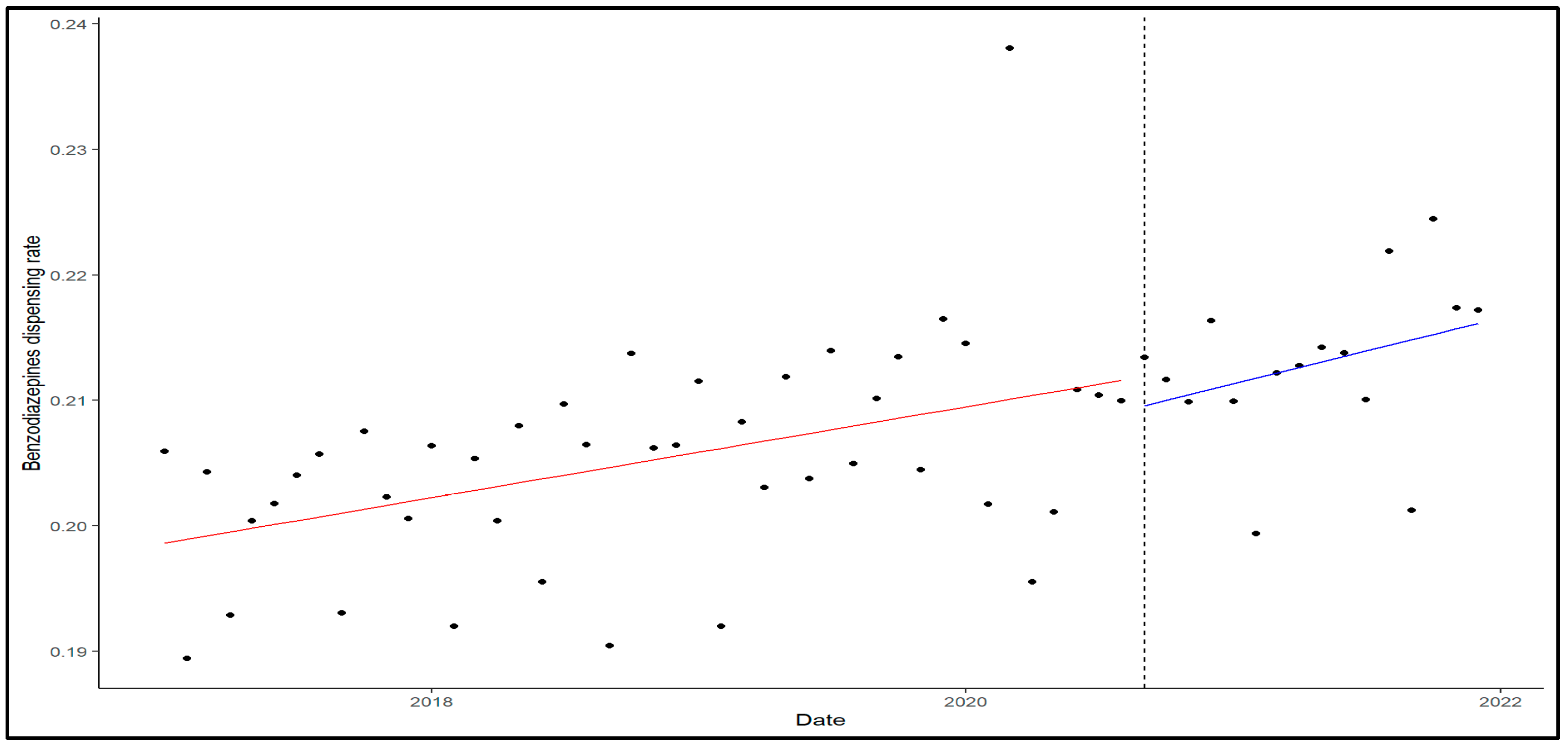

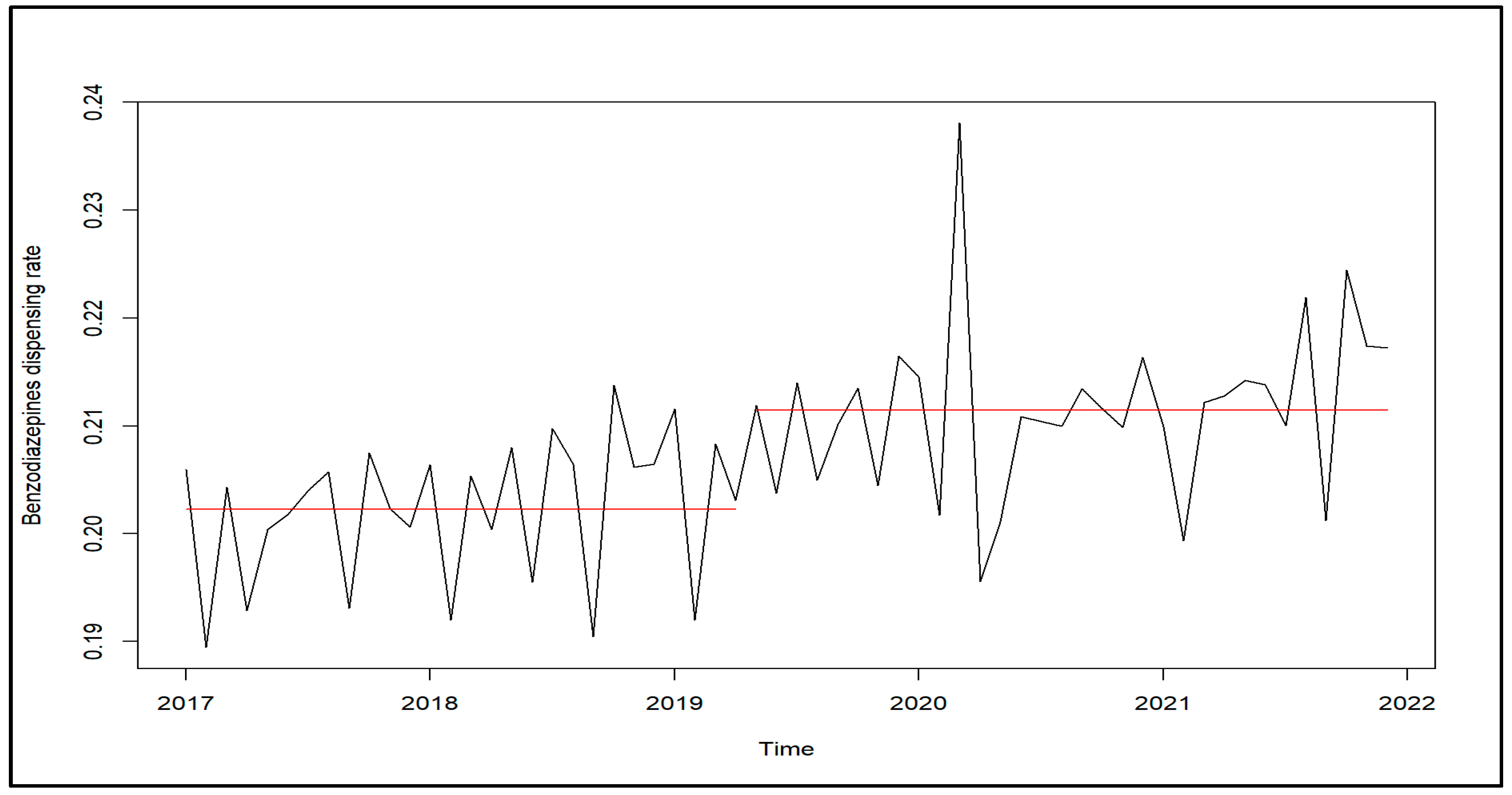

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects and Data Source

4.2. Analyses

4.3. Ethics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBS | Central Bureau of Statistics |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| SSA | Small statistical area |

References

- Murphy, S.; Roberts, R. “Black box” 101: How the Food and Drug Administration evaluates, communicates, and manages drug benefit/risk. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The FDA Development Approval Process. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- O’Connor, N.R. FDA boxed warnings: How to prescribe drugs safely. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 81, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.G. US food and drug administration black box warnings. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2020, 110, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasser, K.E.; Seger, D.L.; Yu, D.T.; Karson, A.S.; Fiskio, J.M.; Seger, A.C.; Shah, N.R.; Gandhi, T.K.; Rothschild, J.M.; Bates, D.W. Adherence to black box warnings for prescription medications in outpatients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Sinha, M.S.; Campbell, E.G.; Schneeweiss, S.; Rausch, P.; Lappin, B.M.; Zhou, E.H.; Avorn, J.; Dal Pan, G.J. Multimodal analysis of FDA drug safety communications: Lessons from zolpidem. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmacy Division—Department of Risk Management and Medicinal Information. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/units/drugs-risk-management-unit/govil-landing-page (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- FDA Requiring Boxed Warning Updated to Improve Safe Use of Benzodiazepine Drug Class-FDA Drug Safety Podcast. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-drug-safety-podcasts/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Griffin, C.E.; Kaye, A.M.; Bueno, F.R.; Kaye, A.D. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner. J. 2013, 13, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benzodiazepines Drug Profile. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/drug-profiles/benzodiazepines_en (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Uzun, S.; Kozumplik, O.; Jakovljević, M.; Sedić, B. Side effects of treatment with benzodiazepines. Psychiatr. Danub. 2010, 22, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brett, J.; Murnion, B. Management of benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. Aust. Prescr. 2015, 38, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinoff, A.N.; Nix, C.A.; Hollier, J.; Sagrera, C.E.; Delacroix, B.M.; Abubakar, T.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.M.; Kaye, A.D. Benzodiazepines: Uses, dangers, and clinical considerations. Neurol. Int. 2021, 13, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, S.A.; Raji, M.A.; Chen, L.; Kuo, Y.-F. Trends in the use of benzodiazepines, Z-hypnotics, and serotonergic drugs among US women and men before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2131012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhan, R.; Agrawal, A.; Sharma, M. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2020, 11, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinman, M.A.; Low, M.; Balicer, R.D.; Shadmi, E. Epidemic use of benzodiazepines among older adults in Israel: Epidemiology and leverage points for improvement. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dios, C.; Fernandes, B.S.; Whalen, K.; Bandewar, S.; Suchting, R.; Weaver, M.F.; Selvaraj, S. Prescription fill patterns for benzodiazepine and opioid drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2021, 229 Pt A, 109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, M.; King, M.; Schoenbaum, M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Brett, J.; Daniels, B.; Buckley, N.A.; Pearson, S.-A.; Schaffer, A.L. Potentially inappropriate benzodiazepine use in Australian adults: A population-based study (2014–2017). Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2020, 39, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthayakumar, S.; Tadrous, M.; Vigod, S.N.; Kitchen, S.A.; Gomes, T. The effects of COVID-19 on the dispensing rates of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in Canada. Depress. Anxiety 2022, 39, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, N.; Brakoulias, V. The impact of COVID-19 on benzodiazepine usage in psychiatric inpatient units. Australas Psychiatry 2022, 30, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, L.D.; Bicket, M.C.; Hu, H.M.; O’Malley, M.; McLaughlin, E.; Flanders, S.A.; Vaughn, V.M.; Waljee, J.F. Opioid and benzodiazepine prescribing after COVID-19 hospitalization. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 17, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasanagottu, K.; Herzig, S.J. Opioids, benzodiazepines, and COVID-19: A recipe for risk. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 17, 580–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, S. Factors associated with adverse mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Pract. 2023, 5, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welton-Mitchell, C.; Dally, M.; Dickinson, K.L.; Morris-Neuberger, L.; Roberts, J.D.; Blanch-Hartigan, D. Influence of mental health on information seeking, risk perception and mask wearing self-efficacy during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal panel study across 6 U.S. States. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenberg Weisband, Y.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Wolff Sagy, Y.; Krieger, M.; Abu Ahmad, W.; Manor, O. Area-level socioeconomic disparity trends in nutritional status among 5-6-year-old children in Israel. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Points Location Intelligence. Available online: https://points.co.il/en/points-location-intelligence (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Central Bureau of Statistics Israel. Characterization and Classification of Geographical Units by the Socio-Economic Level of the Population 2008. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/DocLib/2013/1530/pdf/e_print.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

| Baseline Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Man | 254,355 (39.8) |

| Woman | 385,149 (60.2) |

| Unknown | 11 (0.0) |

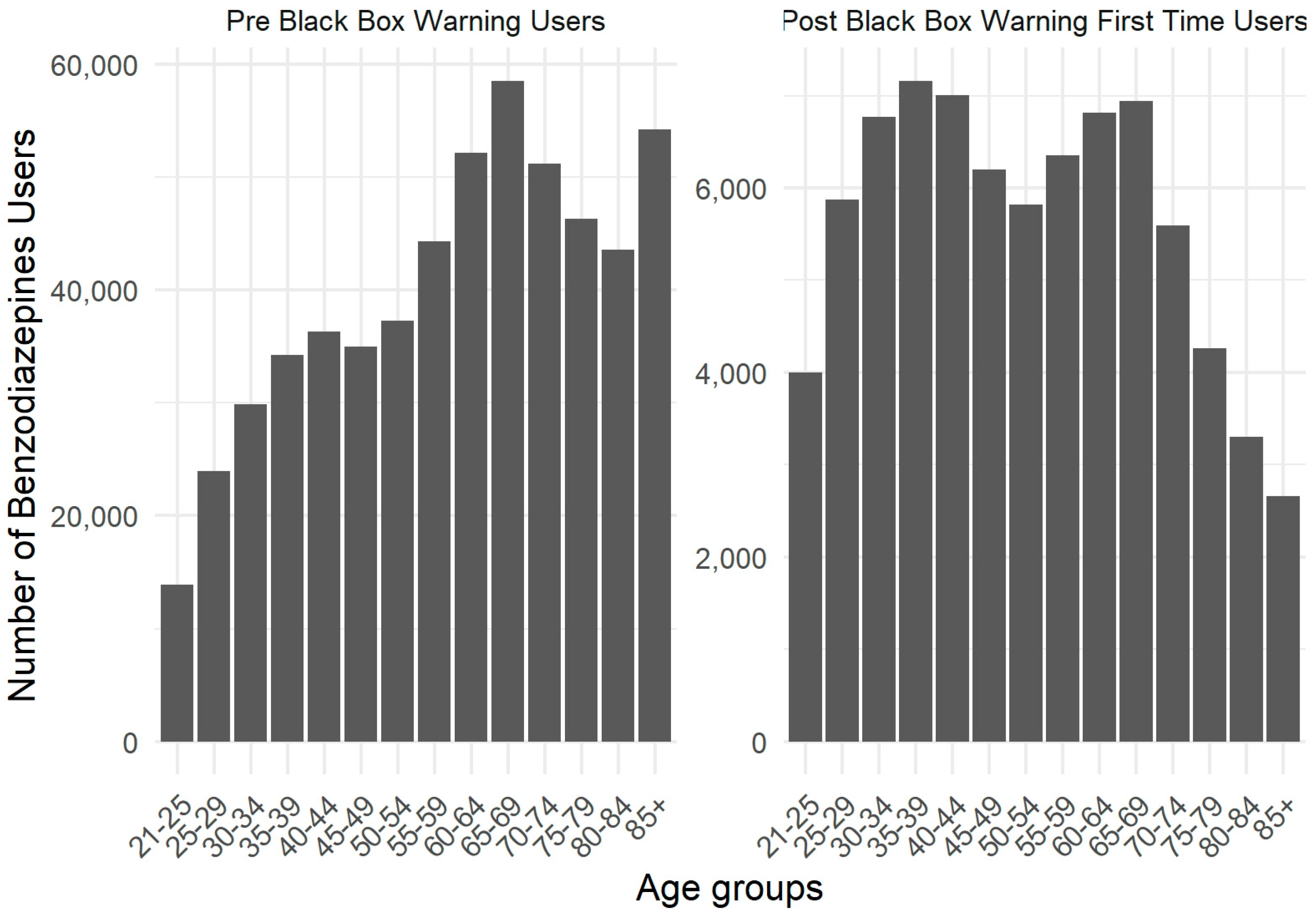

| Age, years 1 | |

| 21–24 | 17,873 (2.8) |

| 25–29 | 29,855 (4.7) |

| 30–34 | 36,679 (5.7) |

| 35–39 | 41,370 (6.5) |

| 40–44 | 43,339 (6.8) |

| 45–49 | 41,171 (6.4) |

| 50–54 | 43,130 (6.7) |

| 55–59 | 50,626 (7.9) |

| 60–64 | 58,963 (9.2) |

| 65–69 | 65,452 (10.2) |

| 70–74 | 56,753 (8.9) |

| 75–79 | 50,542 (7.9) |

| 80–84 | 46,897 (7.3) |

| ≥85 | 56,865 (8.9) |

| Socioeconomic score (0, low; 10, high) | |

| 0 | 24,196 (3.8) |

| 1 | 2980 (0.5) |

| 2 | 16,230 (2.5) |

| 3 | 69,803 (10.9) |

| 4 | 80,782 (12.6) |

| 5 | 97,873 (15.3) |

| 6 | 108,757 (17.0) |

| 7 | 93,385 (14.6) |

| 8 | 78,089 (12.2) |

| 9 | 53,818 (8.4) |

| 10 | 13,602 (2.1) |

| Country of Birth | |

| Israel | 344,253 (53.8) |

| Not Israel | 295,262 (46.2) |

| Ethnic and Religious Distribution | |

| General | 525,978 (82.2) |

| Arab | 76,336 (11.9) |

| Ultra-orthodox | 26,518 (4.1) |

| Unknown | 10,683 (1.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shanwetter Levit, N.; Filosof, K.; Glazer, J.; Goldstein, D.A. Black Box Warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration: The Impact on the Dispensing Rate of Benzodiazepines. Pharmacoepidemiology 2025, 4, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharma4030016

Shanwetter Levit N, Filosof K, Glazer J, Goldstein DA. Black Box Warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration: The Impact on the Dispensing Rate of Benzodiazepines. Pharmacoepidemiology. 2025; 4(3):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharma4030016

Chicago/Turabian StyleShanwetter Levit, Neta, Keren Filosof, Jacob Glazer, and Daniel A. Goldstein. 2025. "Black Box Warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration: The Impact on the Dispensing Rate of Benzodiazepines" Pharmacoepidemiology 4, no. 3: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharma4030016

APA StyleShanwetter Levit, N., Filosof, K., Glazer, J., & Goldstein, D. A. (2025). Black Box Warning by the United States Food and Drug Administration: The Impact on the Dispensing Rate of Benzodiazepines. Pharmacoepidemiology, 4(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharma4030016