The Myokine FGF-21 Responds in a Time-Dependent Manner to Three Different Types of Acute Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Methods

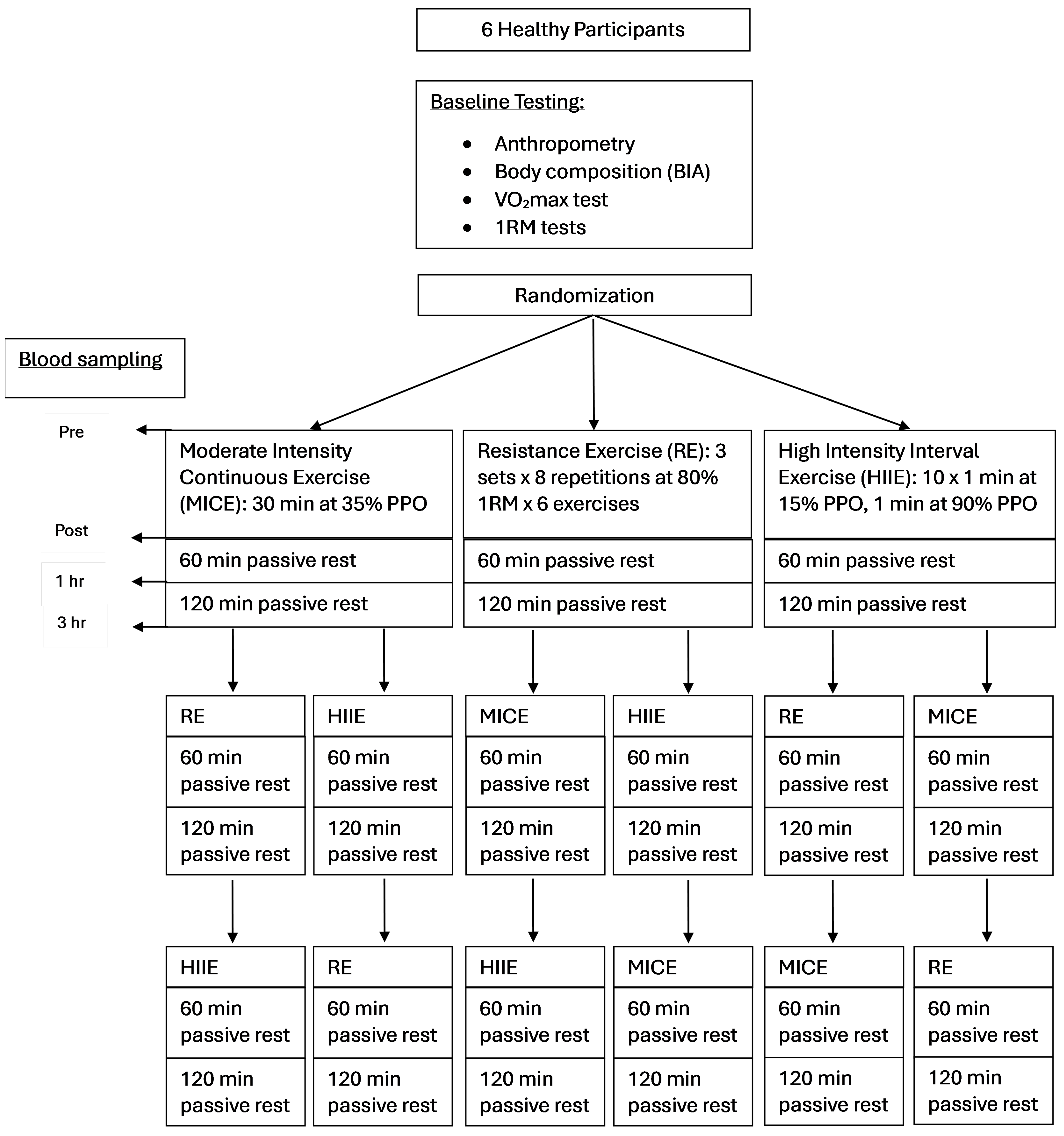

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Sample Size and Participants

4.3. Acute Exercise Sessions

4.4. Blood Sample Analysis

4.5. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.R.; Kwon, K.-S. Potential Roles of Exercise-Induced Plasma Metabolites Linking Exercise to Health Benefits. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 602748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.H.; Moon, K.M.; Min, K.-W. Exercise-Induced Myokines Can Explain the Importance of Physical Activity in the Elderly: An Overview. Healthcare 2020, 8, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, B.; Feehan, J.; Lombardi, G.; Duque, G. Muscle, Bone, and Fat Crosstalk: The Biological Role of Myokines, Osteokines, and Adipokines. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020, 18, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Steensberg, A.; Fischer, C.; Keller, C.; Keller, P.; Plomgaard, P.; Wolsk-Petersen, E.; Febbraio, M. The Metabolic Role of IL-6 Produced during Exercise: Is IL-6 an Exercise Factor? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinel, C.; Lukjanenko, L.; Batut, A.; Deleruyelle, S.; Pradère, J.-P.; Le Gonidec, S.; Dortignac, A.; Geoffre, N.; Pereira, O.; Karaz, S.; et al. The Exerkine Apelin Reverses Age-Associated Sarcopenia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, A.K.; Pontes, W.M.; De Souza, D.M.S.; Prazeres, J.S.F.; Marcucci-Barbosa, L.S.; Santos, J.M.M.; Veira, É.L.M.; Bearzoti, E.; Pinto, K.M.D.C.; Talvani, A.; et al. Strength Training Session Induces Important Changes on Physiological, Immunological, and Inflammatory Biomarkers. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 9675216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Soto, G.; Diaz-Vegas, A.; Casas, M.; Contreras-Ferrat, A.; Jaimovich, E. Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 Potentiates Glucose Transport in Skeletal Muscle Fibers. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020, 65, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Burns, S.F.; Ng, K.K.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Zhong, L.; Tan, F.H.Y.; Chia, K.L.; Fam, K.D.; Yap, M.M.C.; Yeo, K.P.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Mediates the Associations between Exercise, Aging, and Glucose Regulation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, C.; Wang, H.; Foss, R.M.; Clare, M.; George, E.V.; Li, S.; Katz, A.; Cheng, H.; Ding, Y.; et al. Irisin Exerts Dual Effects on Browning and Adipogenesis of Human White Adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 311, E530–E541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Lindley, M.R.; Mastana, S.S.; Nimmo, M.A. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Exercise: Mechanisms and Implications for the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.R.; Pedersen, B.K. The Biological Roles of Exercise-Induced Cytokines: IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.D.; Patra, S.K. Irisin, a Novel Myokine Responsible for Exercise Induced Browning of White Adipose Tissue. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. IJCB 2013, 28, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, B.V.; Paudel, Y.; Thomson, A.M.; Peskett, L.E.; Sénéchal, M. An Examination of Exercise Intensity and Its Impact on the Acute Release of Irisin across Obesity Status: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 49, 1712–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpitts, B.H.; Rioux, B.V.; Eadie, A.L.; Brunt, K.R.; Sénéchal, M. Irisin Response to Acute Moderate Intensity Exercise and High Intensity Interval Training in Youth of Different Obesity Statuses: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Tian, Y.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Huang, C.; Zhao, J.; Hong, P.; He, Z.; Yin, S.; Lucia, A. Myokine Response to High-Intensity Interval vs. Resistance Exercise: An Individual Approach. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, T.; Leung, P.S. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21: A Regulator of Metabolic Disease and Health Span. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 313, E292–E302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zou, T.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; You, J. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21: An Emerging Pleiotropic Regulator of Lipid Metabolism and the Metabolic Network. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porflitt-Rodríguez, M.; Guzmán-Arriagada, V.; Sandoval-Valderrama, R.; Tam, C.S.; Pavicic, F.; Ehrenfeld, P.; Martínez-Huenchullán, S. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Overweight and Obesity. A Systematic Review. Metabolism 2022, 129, 155137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Díez, J.; González, A.; Izquierdo, M. Exercise Training-Induced Changes in Exerkine Concentrations May Be Relevant to the Metabolic Control of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Sport Health Sci. 2023, 12, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.; Rosenbloom, C. Fundamentals of Glycogen Metabolism for Coaches and Athletes. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-Dependent Myokine That Drives Brown-Fat-like Development of White Fat and Thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, A.; Reisi, J.; Kargarfard, M.; Mansourian, M. Differences in the Impact of Various Types of Exercise on Irisin Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse-Patin, A.; Montastier, E.; Vinel, C.; Castan-Laurell, I.; Louche, K.; Dray, C.; Daviaud, D.; Mir, L.; Marques, M.-A.; Thalamas, C.; et al. Effect of Endurance Training on Skeletal Muscle Myokine Expression in Obese Men: Identification of Apelin as a Novel Myokine. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechman, S.E.; Balasekaran, G.; Roth, S.M.; Ferrell, R.E. Association of Interleukin-15 Protein and Interleukin-15 Receptor Genetic Variation with Resistance Exercise Training Responses. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 97, 2214–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J.A.; Leckey, J.J. Carbohydrate Dependence During Prolonged, Intense Endurance Exercise. Sports Med. 2015, 45, S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.P.; Jung, M.E.; Wright, A.E.; Wright, W.; Manders, R.J.F. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Exercise versus Continuous Moderate-Intensity Exercise on Postprandial Glycemic Control Assessed by Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Obese Adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.E.; Peeler, J.D.; Barr, M.; Gardiner, P.F.; Cornish, S.M. The Impact of a Single Bout of Intermittent Pneumatic Compression on Performance, Inflammatory Markers, and Myoglobin in Football Athletes. J. Trainology 2020, 9, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugera, E.M.; Duhamel, T.A.; Peeler, J.D.; Cornish, S.M. The Systemic Myokine Response of Decorin, Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Interleukin-15 (IL-15) to an Acute Bout of Blood Flow Restricted Exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 2679–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta Squared and Partial Eta Squared as Measures of Effect Size in Educational Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | All (n = 6) | Males (n = 4) | Females (n = 2) | t-Test (p-Value) Males vs. Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.83 ± 4.17 | 26.00 ± 4.97 | 28.50 ± 2.12 | 0.55 |

| Height (cm) | 171.57 ± 5.25 | 171.98 ± 3.21 | 170.75 ± 10.25 | 0.82 |

| Mass (kg) | 70.23 ± 10.80 | 71.63 ± 2.94 | 67.45 ± 23.12 | 0.70 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 56.95 ± 9.49 | 60.00 ± 2.82 | 50.85 ± 17.75 | 0.32 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 13.28 ± 5.28 | 11.63 ± 5.08 | 16.60 ± 5.37 | 0.33 |

| Myokine | Exercise Type | Baseline | Immediately Post | 1 h Post | 3 h Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apelin (pg/mL) | MICE | 298.60 ± 156.80 | 266.20 ± 97.09 | 271.95 ± 138.08 | 268.63 ± 131.07 |

| HIIE | 268.27 ± 105.84 | 320.41 ± 147.33 | 281.17 ± 75.02 | 285.51 ± 84.21 | |

| RE | 279.27 ± 142.68 | 280.33 ± 87.14 | 234.65 ± 98.97 | 211.57 ± 112.12 | |

| All | 282.12 ± 129.15 | 288.98 ± 109.31 | 262.59 ± 102.86 | 255.24 ± 109.06 | |

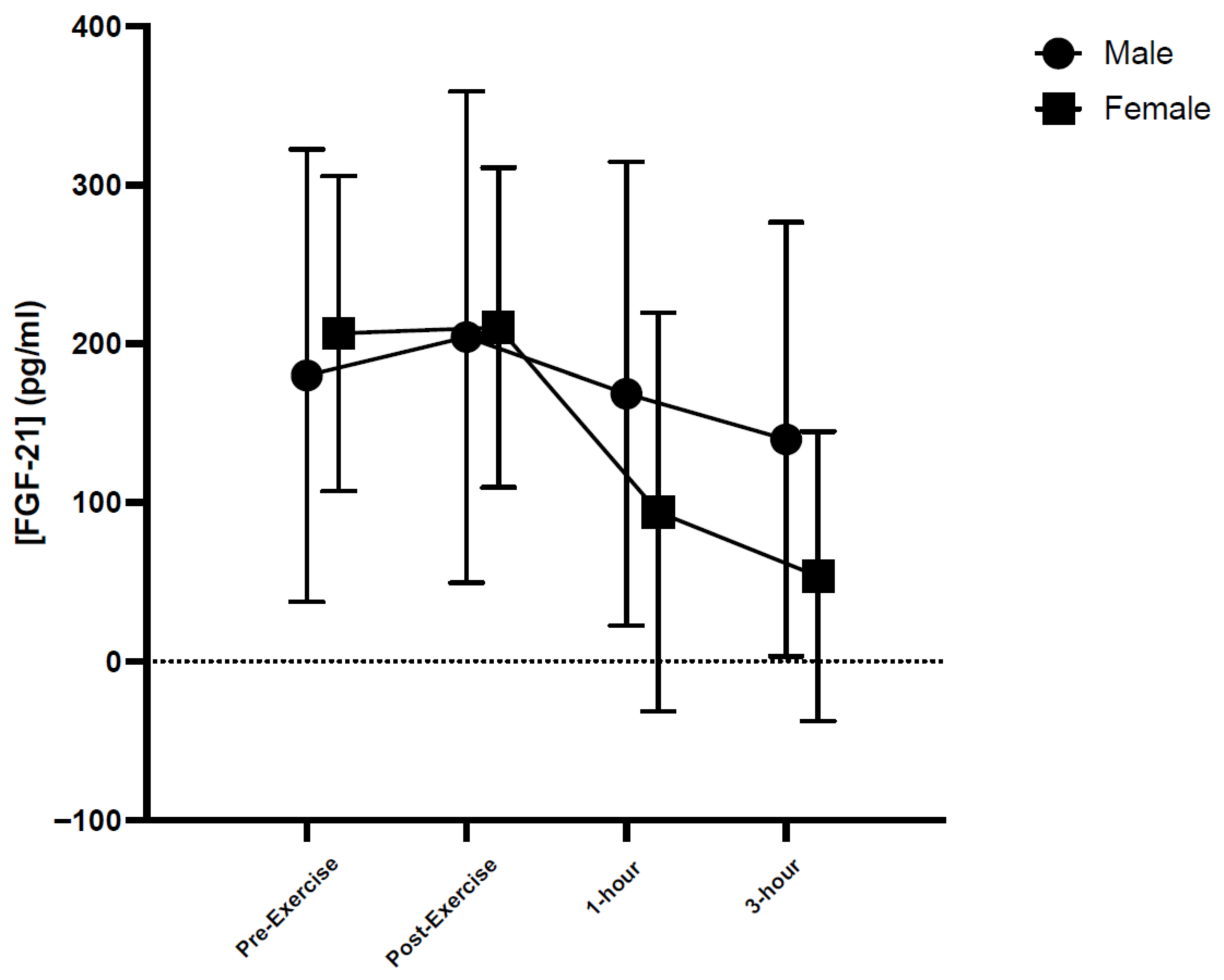

| FGF-21 (pg/mL) | MICE | 162.46 ± 147.27 | 184.58 ± 111.59 | 153.18 ± 153.52 | 113.35 ± 146.17 |

| HIIE | 201.23 ± 119.39 | 217.85 ± 133.89 | 166.52 ± 144.20 | 139.70 ± 98.70 | |

| RE | 203.19 ± 133.86 | 216.38 ± 177.79 | 111.40 ± 144.53 | 80.20 ± 148.88 | |

| All * | 188.96 ± 127.34 | 206.27 ± 135.95 | 143.70 ± 140.62 | 111.08 ± 127.65 | |

| Irisin (pg/mL) | MICE | 1033.59 ± 1322.80 | 633.34 ± 623.35 | 1326.79 ± 834.74 | 1557.02 ± 1196.32 |

| HIIE | 586.43 ± 532.30 | 1838.01 ± 1752.78 | 1312.97 ± 719.21 | 1268.72 ± 1052.58 | |

| RE | 1421.29 ± 1531.44 | 1259.43 ± 1301.57 | 683.90 ± 709.60 | 741.71 ± 624.51 | |

| All | 1013.77 ± 1187.85 | 1243.59 ± 1301.57 | 1107.89 ± 774.84 | 1189.15 ± 991.04 | |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | MICE | 7.51 ± 8.17 | 6.26 ± 5.70 | 5.96 ± 8.23 | 7.61 ± 5.61 |

| HIIE | 9.20 ± 6.39 | 8.89 ± 6.59 | 5.88 ± 6.11 | 6.60 ± 3.08 | |

| RE | 10.48 ± 6.88 | 8.35 ± 8.58 | 5.64 ± 7.01 | 7.49 ± 5.72 | |

| All | 9.06 ± 6.87 | 7.83 ± 6.73 | 5.83 ± 6.74 | 7.24 ± 4.68 | |

| IL-15 (pg/mL) | MICE | 5.53 ± 4.26 | 4.35 ± 2.14 | 5.89 ± 3.66 | 6.12 ± 1.61 |

| HIIE | 4.67 ± 3.20 | 5.73 ± 2.38 | 5.03 ± 2.62 | 4.88 ± 0.90 | |

| RE | 5.51 ± 2.99 | 5.36 ± 2.41 | 5.61 ± 2.41 | 4.41 ± 1.96 | |

| All | 5.24 ± 3.34 | 5.15 ± 2.46 | 5.51 ± 2.80 | 5.14 ± 1.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thrones, M.; Rawliuk, T.; Cordingley, D.M.; Cornish, S.M. The Myokine FGF-21 Responds in a Time-Dependent Manner to Three Different Types of Acute Exercise. Muscles 2026, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles5010003

Thrones M, Rawliuk T, Cordingley DM, Cornish SM. The Myokine FGF-21 Responds in a Time-Dependent Manner to Three Different Types of Acute Exercise. Muscles. 2026; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleThrones, Mikal, Thomas Rawliuk, Dean M. Cordingley, and Stephen M. Cornish. 2026. "The Myokine FGF-21 Responds in a Time-Dependent Manner to Three Different Types of Acute Exercise" Muscles 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles5010003

APA StyleThrones, M., Rawliuk, T., Cordingley, D. M., & Cornish, S. M. (2026). The Myokine FGF-21 Responds in a Time-Dependent Manner to Three Different Types of Acute Exercise. Muscles, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles5010003