Effects of Acute Red Spinach Powder (VitaSpinach®) Ingestion on Muscular Endurance and Resistance Exercise Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plasma Nitrate/Nitrite (NO3/NO2)

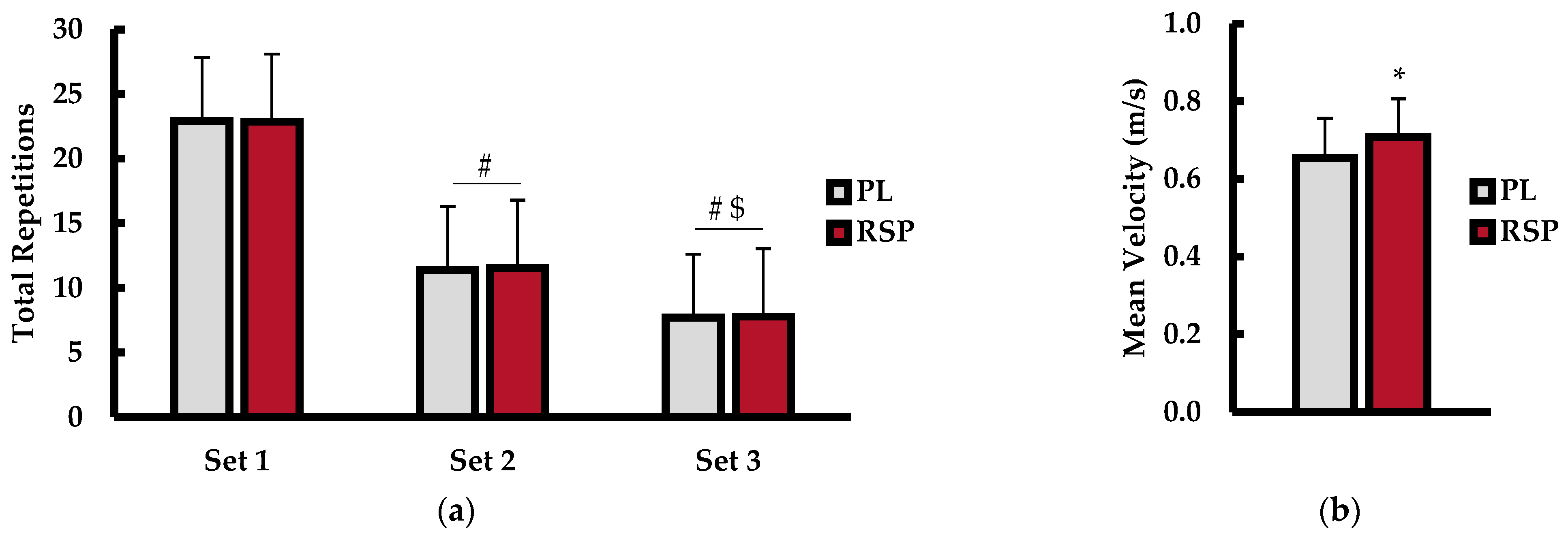

2.2. Repetitions to Exhaustion (RTE) and Mean Velocity

2.3. Global (gRPE) and Local (lRPE) Ratings of Perceived Exertion

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. One-Repetition Maximum (1-RM) and Familiarization

4.4. Supplementation and Plasma NO3/NO2

4.5. Procedures

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebert, A.W.; Wu, T.; Wang, S. Vegetable amaranth (Amaranthus L.); AVRDC Publication: Shanhua, Taiwan, 2011; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, H.A.; Rahmat, A.; Ismail, M.; Rosli, R.; Endrini, S. Potential anticancer effect of red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus) extract. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 13, 396–400. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M.V.; Yount, T.M.; Rogers, R.R.; Ballmann, C.G. Effects of acute red spinach extract ingestion on repeated sprint performance in Division I NCAA female soccer athletes. Oxygen 2023, 3, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linoby, A.; Nurthaqif, M.; Mohamed, M.N.; Mohd Saleh, M.; Md Yusoff, Y.; Md Radzi, N.A.A.; Abd Rahman, S.A.; Mohamed Sabadri, S.N.S. Nitrate-rich red spinach extract supplementation increases exhaled nitric oxide levels and enhances high-intensity exercise tolerance in humans. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Movement, Health and Exercise, Kuching, Malaysia, 30 September–2 October 2019; pp. 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.; Feelisch, M.; Horowitz, J.; Frenneaux, M.; Madhani, M. Pharmacology and therapeutic role of inorganic nitrite and nitrate in vasodilatation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 144, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.C.; Racine, M.L.; Hearon, C.M., Jr.; Kunkel, M.; Luckasen, G.J.; Larson, D.G.; Allen, J.D.; Dinenno, F.A. Acute ingestion of dietary nitrate increases muscle blood flow via local vasodilation during handgrip exercise in young adults. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.C.; Broxterman, R.M.; Smith, J.R.; Allen, J.D.; Barstow, T.J. Effect of dietary nitrate supplementation on conduit artery blood flow, muscle oxygenation, and metabolic rate during handgrip exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 125, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, M.; Christensen, P.M.; Blackwell, J.R.; Hostrup, M.; Jones, A.M.; Bangsbo, J. Nitrate-rich beetroot juice ingestion reduces skeletal muscle O2 uptake and blood flow during exercise in sedentary men. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 5203–5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.D.; Martin, M.P.; Mintz, J.A.; Rogers, R.R.; Ballmann, C.G. Effect of acute beetroot juice supplementation on bench press power, velocity, and repetition volume. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.R.; Davis, A.M.; Rice, A.E.; Ballmann, C.G. Effects of Acute Beetroot Juice Ingestion on Reactive Agility Performance. Oxygen 2022, 2, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Castro, J.M.; Campos-Perez, J.; Ranchal-Sanchez, A.; Durán-López, N.; Domínguez, R. Acute Effects of Beetroot Juice Supplements on Lower-Body Strength in Female Athletes: Double-Blind Crossover Randomized Trial. Sports Health 2022, 14, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchal-Sanchez, A.; Diaz-Bernier, V.M.; De La Florida-Villagran, C.A.; Llorente-Cantarero, F.J.; Campos-Perez, J.; Jurado-Castro, J.M. Acute effects of beetroot juice supplements on resistance training: A randomized double-blind crossover. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Castillo, D.; Raya-González, J.; Domínguez, R.; Bailey, S.J. Beetroot juice supplementation increases concentric and eccentric muscle power output. Original investigation. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Maté-Muñoz, J.L.; Cuenca, E.; García-Fernández, P.; Mata-Ordoñez, F.; Lozano-Estevan, M.C.; Veiga-Herreros, P.; da Silva, S.F.; Garnacho-Castaño, M.V. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on intermittent high-intensity exercise efforts. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Accetta, M.R.; Spitz, R.W.; Mangine, G.T.; Ghigiarelli, J.J.; Sell, K.M. Red spinach extract supplementation improves cycle time trial performance in recreationally active men and women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2541–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.N.; Haun, C.T.; Kephart, W.C.; Holland, A.M.; Mobley, C.B.; Pascoe, D.D.; Roberts, M.D.; Martin, J.S. Red spinach extract increases ventilatory threshold during graded exercise testing. Sports 2017, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.S.; Haun, C.T.; Kephart, W.C.; Holland, A.M.; Mobley, C.B.; McCloskey, A.E.; Roberts, M. The effects of a novel red spinach extract on graded exercise testing performance. In Proceedings of the American College of Sport Medicine Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 31 May–4 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, J.R.; Hart, T.L.; Haynes IV, J.T.; Woods, C.A.; Toy, A.M.; Pihera, B.C.; Aziz, M.A.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Jones, M.D.; Vantrease, W.C. Influence of dietary nitrate supplementation on physical performance and body composition following offseason training in Division I athletes. J. Diet. Suppl. 2022, 19, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Syed, B.; Abed, I.; Manguerra, D.; Shehabat, M.; Razick, D.I.; Nadora, D.; Nadora, D.; Akhtar, M.; Pai, D. Improved Effect of Spinach Extract on Physical Performance: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus 2025, 17, e77840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes IV, J.T.; Townsend, J.R.; Aziz, M.A.; Jones, M.D.; Littlefield, L.A.; Ruiz, M.D.; Johnson, K.D.; Gonzalez, A.M. Impact of red spinach extract supplementation on bench press performance, muscle oxygenation, and cognitive function in resistance-trained males. Sports 2021, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, M.; Jansson, E.Å.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. The increase in plasma nitrite after a dietary nitrate load is markedly attenuated by an antibacterial mouthwash. Nitric Oxide 2008, 19, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, A.; Schiffer, T.A.; Ivarsson, N.; Cheng, A.J.; Bruton, J.D.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Westerblad, H. Dietary nitrate increases tetanic [Ca2+] i and contractile force in mouse fast-twitch muscle. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 3575–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J.; Gamu, D.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Van Loon, L.J.; Spriet, L.L.; Tupling, A.R.; Holloway, G.P. Beetroot juice increases human muscle force without changing Ca2+-handling proteins. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 2016–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggan, A.R.; Peterson, L.R. Dietary nitrate enhances the contractile properties of human skeletal muscle. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2018, 46, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacramento, H.S.; da Silva, L.C.; Papoti, M.; Rossi, F.E.; dos Santos Gomes, W.; dos Santos Costa, A.; Campos, E.Z. Sodium nitrate improves oxidative energy contribution and reduces phosphocreatine contribution during high-intensity intermittent exercise. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2025, 96, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husmann, F.; Bruhn, S.; Mittlmeier, T.; Zschorlich, V.; Behrens, M. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves exercise tolerance by reducing muscle fatigue and perceptual responses. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 432050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.K.; Granner, D.K.; Mayes, P.A.; Rodwell, V.W. Harper’s Illustrated Biochemistry; McGraw Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, K.A.; Swenson, J.D.; Vanhaitsma, T.A.; Hughen, R.W.; Jo, D.; Light, K.C.; Schweinhardt, P.; Amann, M.; Light, A.R. Exogenously applied muscle metabolites synergistically evoke sensations of muscle fatigue and pain in human subjects. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcora, S.M.; Staiano, W. The limit to exercise tolerance in humans: Mind over muscle? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ballmann, C.G.; Cook, G.D.; Hester, Z.T.; Kopec, T.J.; Williams, T.D.; Rogers, R.R. Effects of Preferred and Non-Preferred Warm-Up Music on Resistance Exercise Performance. J. Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebe, D.; Ehrman, J.K.; Liguori, G.; Magal, M.; American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Wolters Kluwer: Alfen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.D.; Langley, H.N.; Roberson, C.C.; Rogers, R.R.; Ballmann, C.G. Effects of Short-Term Golden Root Extract (Rhodiola rosea) Supplementation on Resistance Exercise Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Bae, S.; Kim, Y.; Cho, C.-H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-P.; Kim, H.-R.; Hwang, Y.-I.; Kang, J.S. Vitamin C prevents stress-induced damage on the heart caused by the death of cardiomyocytes, through down-regulation of the excessive production of catecholamine, TNF-α, and ROS production in Gulo (−/−) Vit C-insufficient mice. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bada, A.; Svendsen, J.; Secher, N.; Saltin, B.; Mortensen, S. Peripheral vasodilatation determines cardiac output in exercising humans: Insight from atrial pacing. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 2051–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrell, H.F.; Moore, J.M.; Smith, M.F.; Gee, T.I. Validity and reliability of a linear positional transducer across commonly practised resistance training exercises. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orange, S.T.; Metcalfe, J.W.; Marshall, P.; Vince, R.V.; Madden, L.A.; Liefeith, A. Test-retest reliability of a commercial linear position transducer (GymAware PowerTool) to measure velocity and power in the back squat and bench press. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, M.; Aybek, E. Jamovi: An easy to use statistical software for the social scientists. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2019, 6, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, A.B. Fundamental Statistical Concepts and Techniques in the Biological and Environmental Sciences: With Jamovi; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Characteristics (n = 14) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23.1 ± 6.3 |

| Height (cm) | 174.2 ± 11.7 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 76.7 ± 10.4 |

| RT Experiences (years) | 6.4 ± 6.9 |

| 1-RM (kg) | 104.3 ± 20.7 |

| Relative 1-RM (1-RM/Body mass) | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, H.M.; Porrill, S.L.; Rogers, R.R.; Jose-Gomez, J.; Wright, R.E.; Spears, P.N.; Ballmann, C.G. Effects of Acute Red Spinach Powder (VitaSpinach®) Ingestion on Muscular Endurance and Resistance Exercise Performance. Muscles 2025, 4, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4040060

Nguyen HM, Porrill SL, Rogers RR, Jose-Gomez J, Wright RE, Spears PN, Ballmann CG. Effects of Acute Red Spinach Powder (VitaSpinach®) Ingestion on Muscular Endurance and Resistance Exercise Performance. Muscles. 2025; 4(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Haley M., Sophia L. Porrill, Rebecca R. Rogers, Josselyn Jose-Gomez, Rachel E. Wright, Phoebe N. Spears, and Christopher G. Ballmann. 2025. "Effects of Acute Red Spinach Powder (VitaSpinach®) Ingestion on Muscular Endurance and Resistance Exercise Performance" Muscles 4, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4040060

APA StyleNguyen, H. M., Porrill, S. L., Rogers, R. R., Jose-Gomez, J., Wright, R. E., Spears, P. N., & Ballmann, C. G. (2025). Effects of Acute Red Spinach Powder (VitaSpinach®) Ingestion on Muscular Endurance and Resistance Exercise Performance. Muscles, 4(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4040060