Proliferation of Plastic Packaging and Its Environmental Impacts at the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 in Togo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

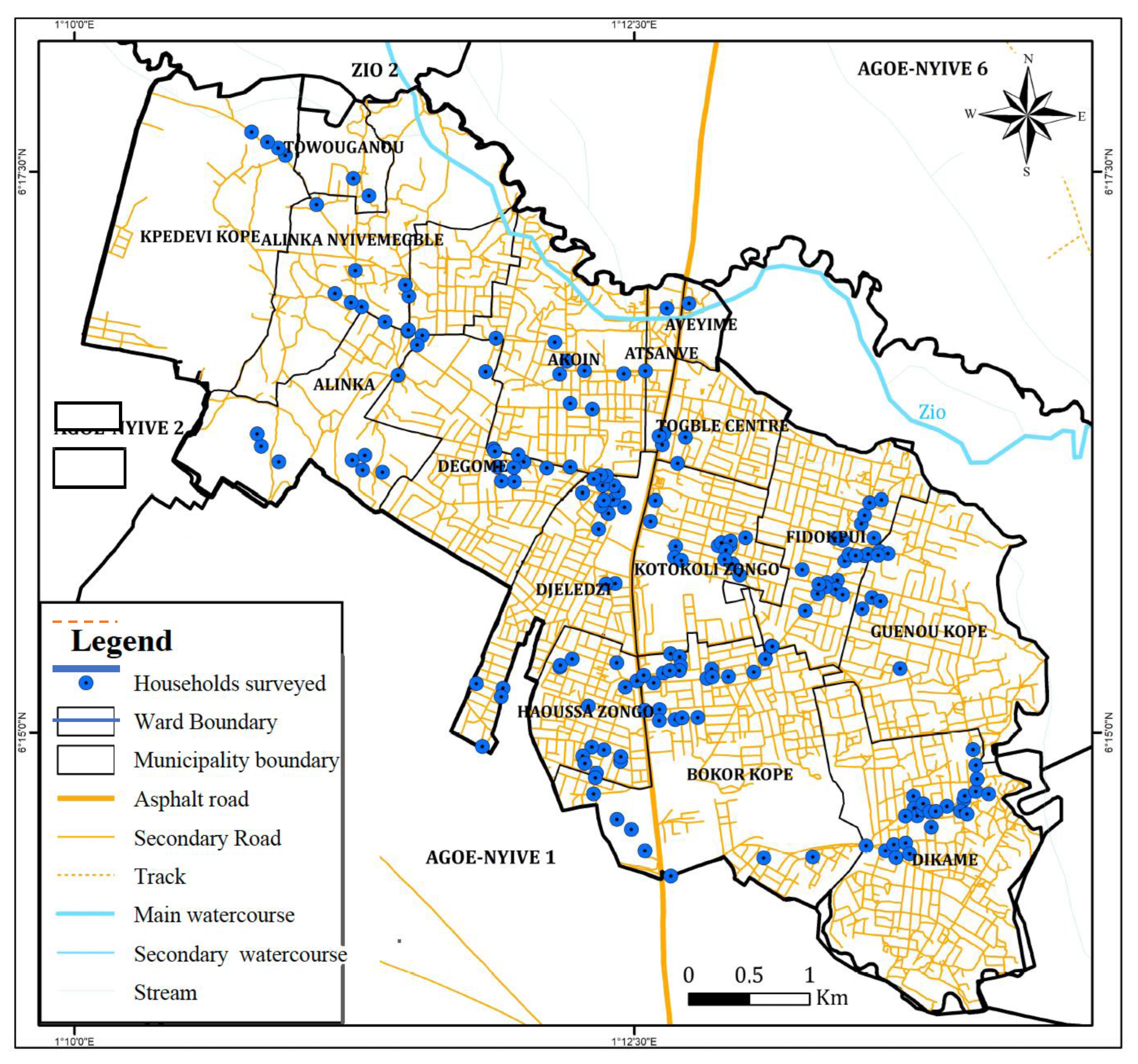

2.1. Location of the Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.3.1. Document Search

2.3.2. Field Observations

2.3.3. Neighborhood Selection and Sample Determination

2.3.4. Interviews

2.3.5. Survey Questionnaire

- ❖

- Questionnaire design

- ❖

- Pre-test and questionnaire administration

3. Results

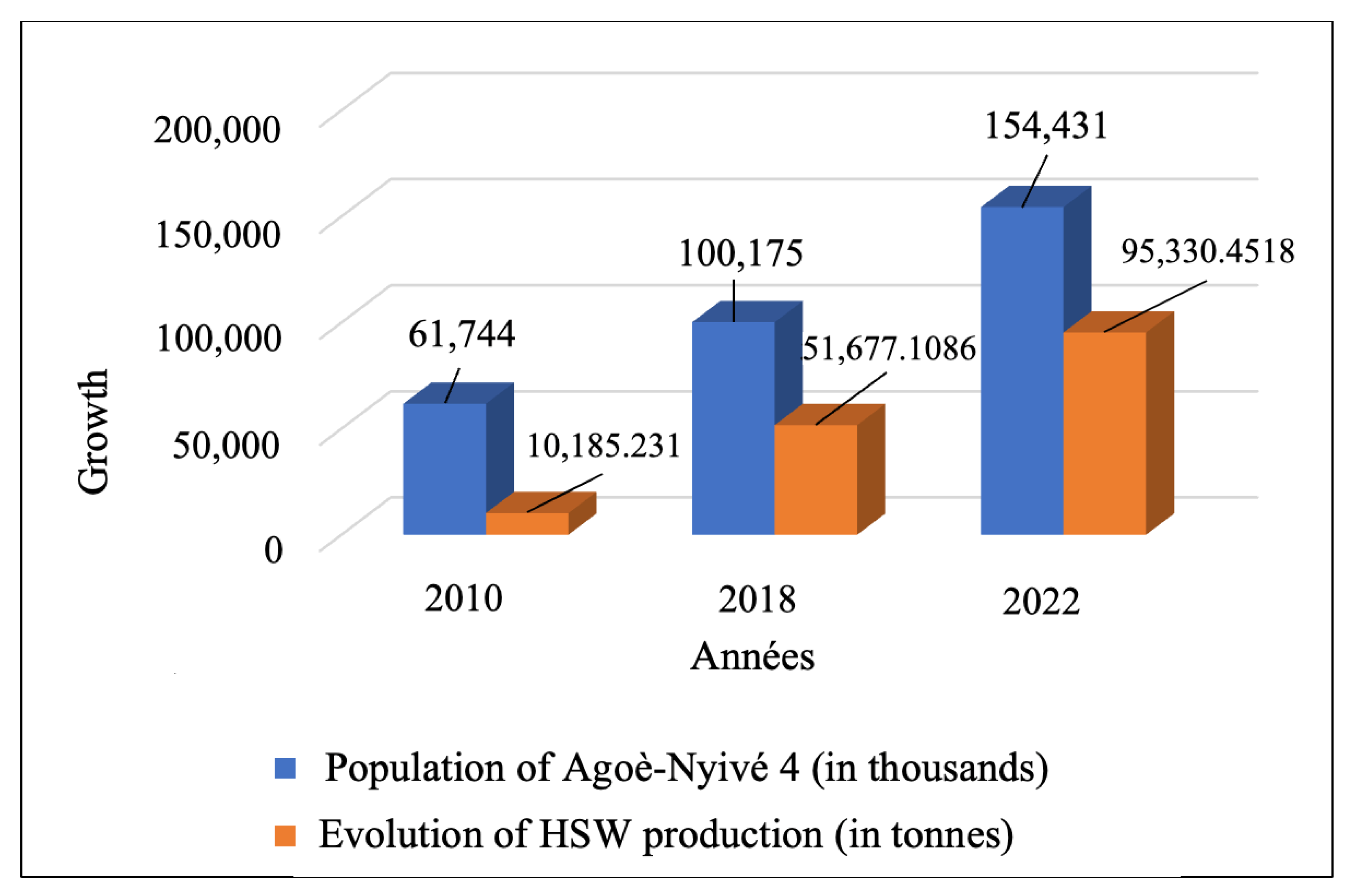

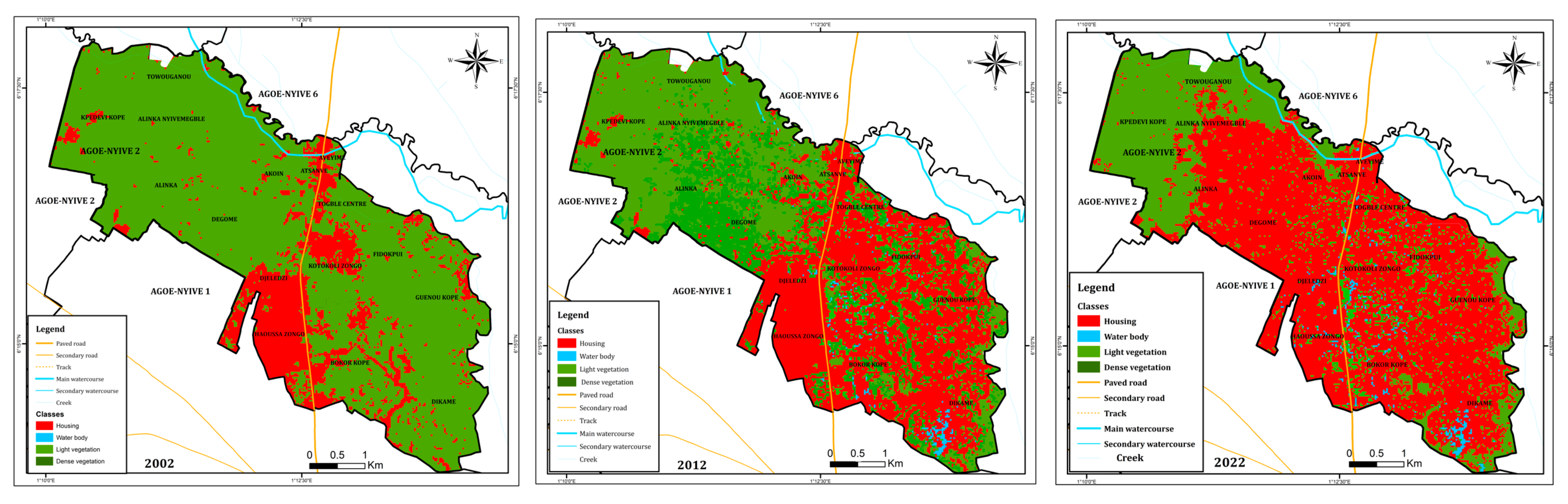

3.1. Rapid Population Growth: A Contributing Factor to the Increase in Household Plastic Waste

3.2. Socio-Professional Situation of Respondents Dominated by the Small Street Trader

- ❖

- Reasons for using plastic bags

- ❖

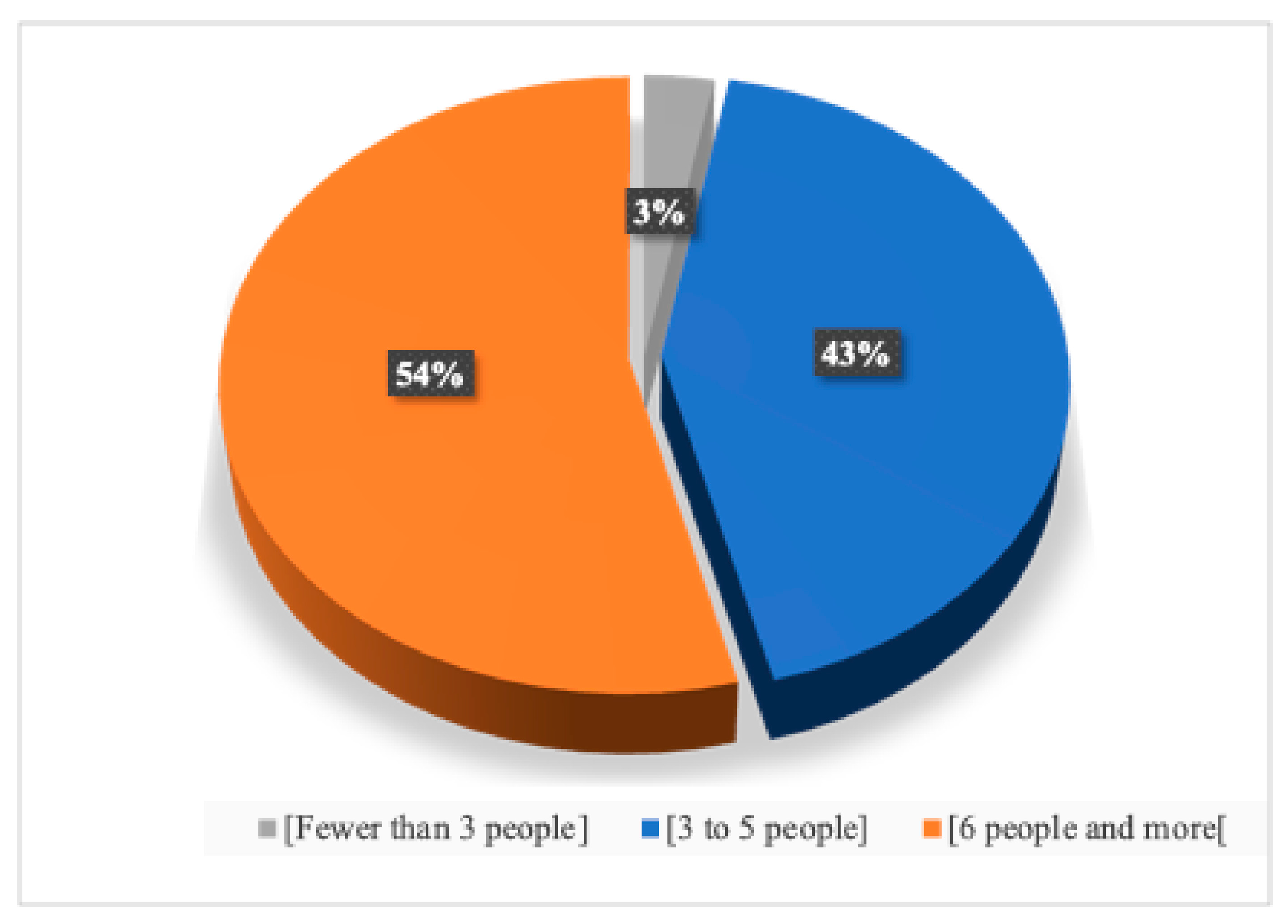

- A large household size in the commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4, a source of abundant plastic waste production

3.3. The Environmental Impacts Caused by Plastic Waste in the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4

- ❖

- The state of the commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 during the rainy season.

- ❖

- Plastic waste clogs water drainage systems.

- ❖

- Flood and Health Risks Associated with Plastic Waste Accumulation in Agoè-Nyivé 4

4. Discussion

4.1. Source of the Proliferation of Plastic Waste

4.2. Household Plastic Waste Generation

4.3. Access to Collection Services and Household Practices

4.4. Environmental Impacts of Plastic Packaging

4.5. Reducing Plastic Waste and Its Impacts

4.6. Policy and Governance Implications

4.7. Limitations and Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kabore, S.G. Les Représentations Sociales du Déchet Dans la Ville de Ouagadougou: Le cas des Déchets Plastiques. Mémoire de Maîtrise, Unité de Formation et de Recherche en Sciences Humaines (UFR/SH), Département de Sociologie, Université de Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 94 p. 2008 2009. Available online: https://fr.scribd.com/document/519578238/A39-Memoire-Georgette-Kabore-Version-Finale (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.W.Y.; Shiran, Y.; Bailey, R.M.; Cook, E.D.; Stuchtey, M.R.; Koskella, J.; Velis, C.A.; Godfrey, L.; Boucher, J.; Murphy, M.B.; et al. Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjalo, D.K.; Houedakor, K.Z.; Zinsou-Klassou, K. Usage des emballages plastiques dans la restauration de rue et assainis-599 sement des villes ouest-africaines: Exemple de Lomé au Togo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepota, K.; Premlall, K.; Mabuza, M. Compositional Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste from Tshwane Metropolitan Landfill Sites in South Africa for Potential Sustainable Management Strategies. Waste 2025, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; McGivern, A.; Murphy, E.; Jambeck, J.; Leonard, G.H.; Hilleary, M.A.; et al. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.C.; Tse, H.F.; Fok, L. Plastic waste in the marine environment: A review of sources, occurrence and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophie, R.W.; Pacome, G.K.K.; Aminata, G.; Kelety, C.; Barthélemy, T.; Vinciale, A.A.W.; Boubacar, N.; Ngangue, P. Impact of Plastic Waste on the Human Health in Low-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J. Environ. Prot. 2024, 15, 572–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, M.K.; Wivine, M.K.; Jean-Claude, N.M.; Véronique, M.T.; Irène, K.D.S. Problématique d’emballages plastiques à Kinshasa: Facteurs d’adoption du comportement écologique des ménages. Rev. Française D’economie Et De Gest. 2023, 4, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbekley, E.H.; Nyakpo, A.; Adjalo, K.D.; Gbekley, A.-S.H.; Tchacondo, T. Urban governance and solid household waste management in Togo: Case of the town of Vogan in Togo (West Africa). Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koledzi, K.E.; Baba, G.; Agbebavi, J.; Koffi, D.; Matejka, G. Gestion des déchets dans les villes en développement: Transfert, adaptation de schéma et sources de financement. Déchets Sci. Et Tech. 2014, 68, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M. Microplastics research—From sink to source. Science 2018, 360, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Shu, C.; Wang, D.; Song, J.; Song, Y.; Zhen, W.; Feng, Z.; Wu, G. Isolation of 2019-nCoV from a stool specimen of a laboratory-confirmed case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). China CDC Wkly. 2020, 2, 123. [Google Scholar]

- De-la-Torre, G.E.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C.; Pizarro-Ortega, C.I.; Santillán, L. New plastic formations in the Anthropocene. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and human health: A micro issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.; Vinoda, K.S.; Papireddy, M.; Gowda, A.N.S. Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste—A Review. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboaa, C.; Tetteh, E.K.; Chollom, M.N.; Rathilal, S. Sustainable Solutions for Plastic Waste Mitigation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Future Perspectives Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Teye, G.K.; Dinis, M.A.P. Barriers and Challenges to Waste Management Hindering the Circular Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakime, T.-H.; Komi, K.; Adjonou, K.; Hlovor, A.K.D.; Gbafa, K.S.; Oyedele, P.B.; Polorigni, B.; Kokou, K. Derivation of a GIS-Based Flood Hazard Map in Peri-Urban Areas of Greater Lomé, Togo (West Africa). Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safougne Djomekui, B.L.; Ngouanet, C.; Smit, W. Urbanization and Health Inequity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examining Public Health and Environmental Crises in Douala, Cameroon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velis, C.A.; Hardesty, B.D.; Cottom, J.W.; Wilcox, C. Enabling the informal recycling sector to prevent plastic pollution and deliver an inclusive circular economy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 138, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoe, C.A.; Effebi, K.R.; Kanga, N.M.; Krou, H.A.; Yao, K.J.E. Mode de gestion des sachets plastiques et perception des ménages dans la ville d’Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Afr. Sci. 2024, 24, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mouloungui Kussu, L.B.; Zoo Eyindanga, R.C.; Vimenyo, M.; Ngawandji, B.N.; Fiagan, K.-A.; Mambani, J.-B. Physical Characterisation and Analysis of the Perception of Potential Risks Associated with the Proliferation of Solid Waste along the Lomé Coastline in Togo. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Opoku, E.E.O. Environmental degradation and economic growth: Investigating linkages and potential pathways. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambiani, K.; Lare, Y.; Zanguina, A.; Narra, S. Physicochemical properties and energy potential of combustible municipal solid waste from Lomé, Togo. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2024, 17, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguedou, E.; Narra, S.; Agboka, K.; Kongnine, D.M.; Afrakoma Armoo, E. Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management. Waste 2023, 1, 654–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouye, I.; Adjoussi, D.P.; Ndione, J.A.; Sall, A.; Adjaho, K.D.; Gomez, M.L.A. Coastline dynamics analysis in dakar region, Senegal from 1990 to 2040. Am. J. Clim. Change 2022, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Togo, UNICEF, et UNDP, Togo Population and Housing Census 2022 (RGPH-5). INSEED—Directorate General of Statistics and National Accounts, Lomé, Togo. 2022. [En ligne]. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/togo-population-and-housing-census-2022 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Togolese Republic, Law No. 2019-006 of 26 June 2019 on the Organization of Municipalities. 2019. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/Tog144583.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Anoumou, K.R.; Sondou, T. Photography in urban studies in Greater Lomé, an objectifying approach? J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.; Meyer, M. Photographier les Paysages Sociaux Urbains: Itinéraires Visuels Dans la Ville. In Ethnographiques.org, n°17 Novembre (2008). L’éthique en Anthropologie de la Santé: Conflits, Pratiques, Valeur Heuristique [en ligne]. Available online: http://www.ethnographiques.org/2008/Du,Meyer.html (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Ikart, E.M. Survey Questionnaire Survey Pretesting Method: An Evaluation of Survey Questionnaire via Expert Reviews Technique. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiankpa, Y. Insalubrité et Gestion des Déchets Ménagers dans la Ville de Lomé au Togo. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akindele, E.O.; Alimba, C.G. Plastic pollution threat in Africa: Current status and implications for aquatic ecosystem health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 7636–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Van Velthoven, C.T.J.; Nguyen, T.N.; Goldy, J.; Sedeno-Cortes, A.E.; Baftizadeh, F.; Bertagnolli, D.; Casper, T.; Chiang, M.; Crichton, K.; et al. A taxonomy of transcriptomic cell types across the isocortex and hippocampal formation. Cell 2021, 184, 3222–3241.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyathi, B.; Togo, C.A. Overview of Legal and Policy Framework Approaches for Plastic Bag Waste Management in African Countries. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 8892773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro-Appiah, K.; Scheinberg, A.; Mensah, A.; Afful, A.; Boadu, H.K.; De Vries, N. Assessment of the municipal solid waste management system in Accra, Ghana: A ‘Wasteaware’ benchmark indicator approach. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2017, 35, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjalo, D. Le développement de la filière plastique et son impact socioéconomique et environnemental dans la ville de Lomé. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zurbrügg, C.; Gfrerer, M.; Ashadi, H.; Brenner, W.; Küper, D. Determinants of sustainability in solid waste management–The Gianyar Waste Recovery Project in Indonesia. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Wal, E.; Festa-Bianchet Réale, D.; Coltman, D.W.; Pelletier, F. Sex-based differences in the adaptive value of social behavior contrasted against morphology and environment. Ecology 2015, 96, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, A.L.; Kawaguchi, S.; King, C.K.; Townsend, K.A.; King, R.; Huston, W.M.; Bengtson Nash, S.M. Turning microplastics into nanoplastics through digestive fragmentation by Antarctic krill. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrady, A.L. The plastic in microplastics: A. review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achigan-Dako, E.G.; Tchokponhoué, D.A.; N’Danikou, S.; Gebauer, J.; Vodouhè, R.S. Current knowledge and breeding perspectives for the miracle plant Synsepalum dulcificum (Schum. et Thonn.) Daniell. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campitelli, A.; Schebek, L. How is the performance of waste management systems assessed globally? A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Harrison, J.; Rooney, D.W. Pyrolysis kinetic modelling of abundant plastic waste (PET) and in-situ emission monitoring. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeru, J. The urban political ecology of plastic bag waste problem in Nairobi, Kenya. Geoforum 2006, 6, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.C.; Velis, C.; Cheeseman, C. Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batcham, I.; Adjalo, D.K.; Houedakor, K.Z.; Tede, K.K.E.; Zinsou-Klassou, K. Proliferation of Plastic Packaging and Its Environmental Impacts at the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 in Togo. Waste 2025, 3, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste3040038

Batcham I, Adjalo DK, Houedakor KZ, Tede KKE, Zinsou-Klassou K. Proliferation of Plastic Packaging and Its Environmental Impacts at the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 in Togo. Waste. 2025; 3(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste3040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatcham, Ibrahim, Djiwonou Koffi Adjalo, Koko Zébéto Houedakor, Komlan Kounon Etienne Tede, and Kossiwa Zinsou-Klassou. 2025. "Proliferation of Plastic Packaging and Its Environmental Impacts at the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 in Togo" Waste 3, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste3040038

APA StyleBatcham, I., Adjalo, D. K., Houedakor, K. Z., Tede, K. K. E., & Zinsou-Klassou, K. (2025). Proliferation of Plastic Packaging and Its Environmental Impacts at the Commune of Agoè-Nyivé 4 in Togo. Waste, 3(4), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste3040038