Classification of Music Space from the Perspective of Information Philosophy †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

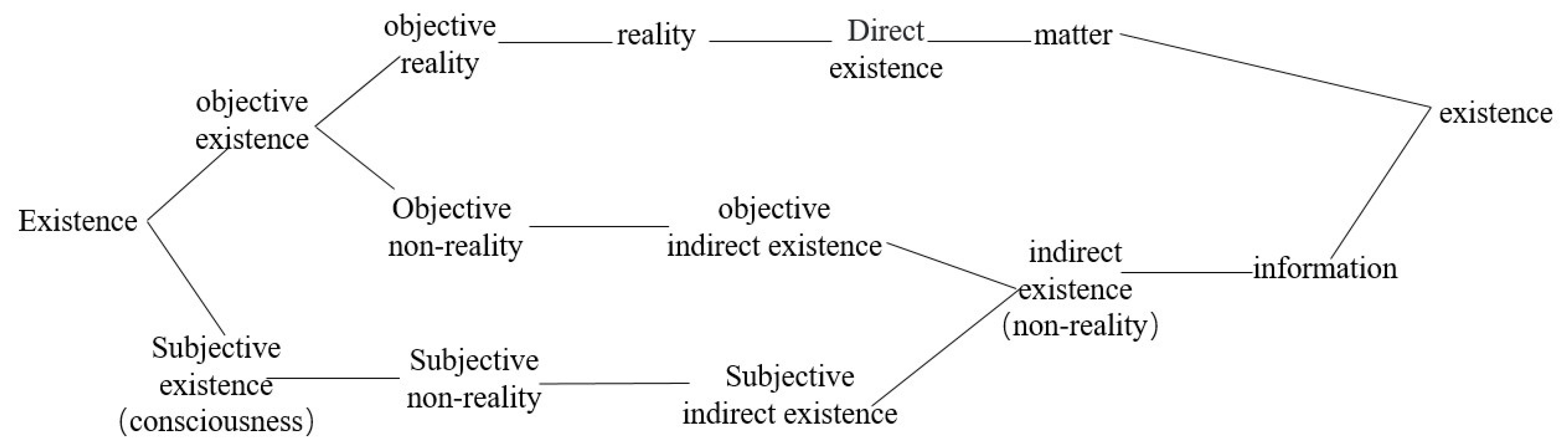

2. An Overview of the Division of Existence Domains in Information Philosophy

3. General Classification of Music Space Types

3.1. Musical Space that Differs from that of Other Arts

3.2. General Division of Music Space Types

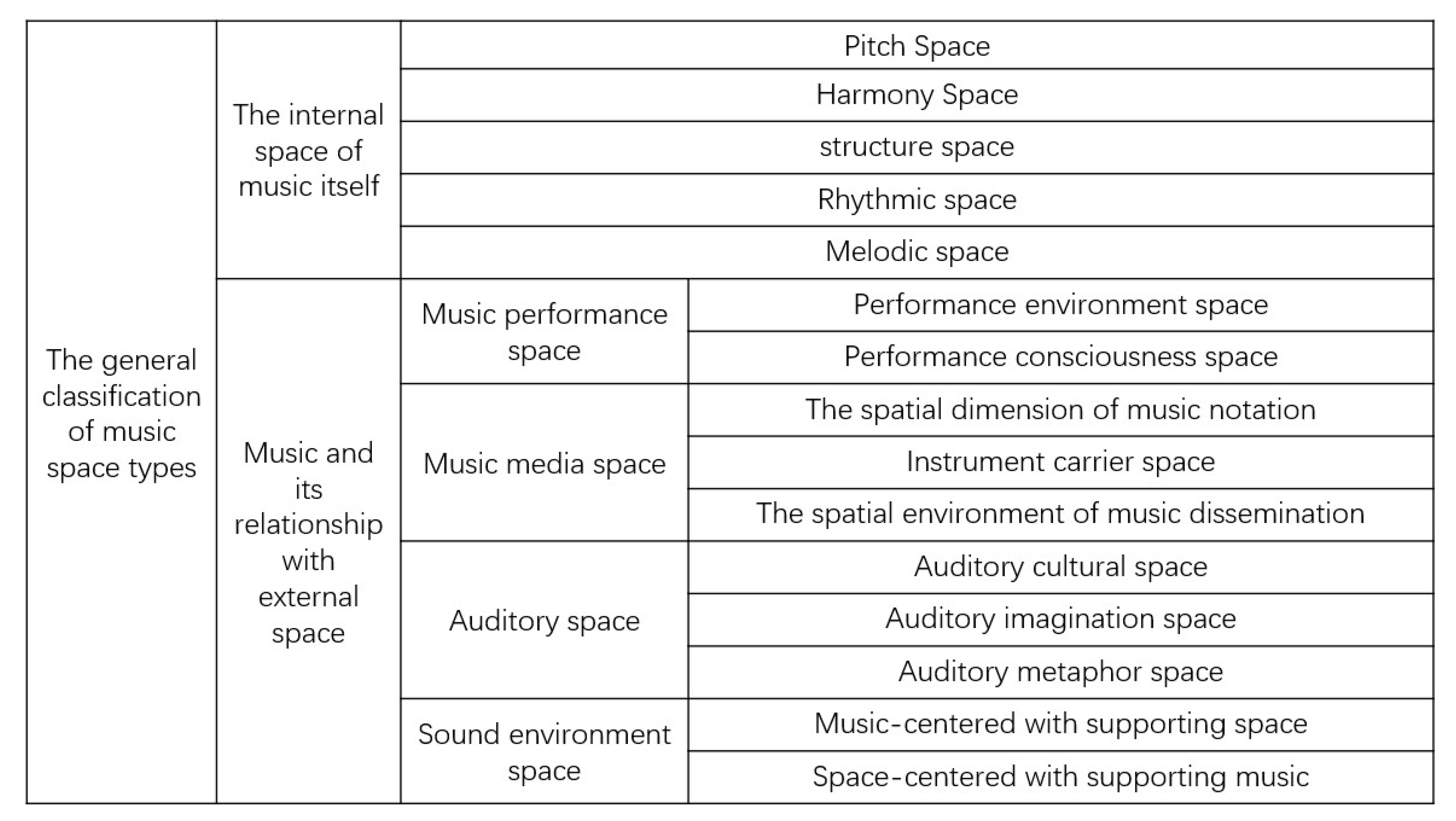

- After the spatiality of music is revealed, it is necessary to classify the types of music space. We can roughly divide music into two categories: internal relational space and external relational space.

- First, the internal space of music, as the name implies, refers to the types of spaces related to the compositional elements of music, such as pitch space, harmony space, formal structure space, rhythm space, melody space, tonality space, and so on.

- Second, the external spatial relationships of music include a wide range of elements, which can be roughly divided into the performance space, media space, auditory space, and sound environment space. The performance space can be divided into performance environment space and performance consciousness space. The music media space can be divided into music score carrier space, pronunciation instrument space (the resonance cavity space of instruments directly affects the timbre and volume), and communication environment space (music hall, record playing space, small chamber music, etc.).

- Auditory space refers to the dynamic relationship between music and people, where a reciprocal interaction occurs between the musical works and the auditory perception of the subject. This space can be further categorized into cultural, metaphorical, imaginative, and other dimensions. The external sound environment space can be classified into two main types; one is music-centric with space as a supplement, such as theater music, and the other is space-centric with music as a supplement, such as ritual music, labor songs, ambient music in restaurants, etc. The types of music spaces summarized above are shown in Figure 2.

4. The Classification of Music Space Types in Information Philosophy

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kun, W.U. The Philosophy of Information; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stravinsky, I. Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons; Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press: Shanghai, China, 2014; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. The Space-Time Effect of Music; Art of Music: Shanghai, China, 1991; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, S.K. Emotion and Form; Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1986; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S. Classification of Music Space from the Perspective of Information Philosophy. Comput. Sci. Math. Forum 2023, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2023008018

Zhang S. Classification of Music Space from the Perspective of Information Philosophy. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum. 2023; 8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2023008018

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shan. 2023. "Classification of Music Space from the Perspective of Information Philosophy" Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum 8, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2023008018

APA StyleZhang, S. (2023). Classification of Music Space from the Perspective of Information Philosophy. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2023008018