Abstract

The purpose of this study was to establish a quantitative method to classify lingual frenulum as normal and altered. Methods: 98 people were included in this study. All measurements were made with maxium opening of the mouth. A digital caliper was used to measure the length of the frenulum under three conditions: a) with the tongue tip on the incisal papilla; b) with the tongue sucked up and maintained against the hard palate; and c) with tongue stretching over a spatula. Results: observations indicated that the most useful and statistically significant way of measuring frenulum length was achieved with maximum mouth opening and the tongue tip on the incisal papilla. Conclusion: this quantitative method was demonstrated to be effective for identifying and distinguishing normal and altered frenular length.

INTRODUCTION

Speech therapists find many patients with

various complaints leading to the hypothesis

that some alteration in the anatomy of the

lingual frenulum (or frenum) is the cause for

the problems, or at least, may aggravate

them. The most common symptoms that

may raise such hypotheses would be:

imprecision of speech; soft /r/ phoneme with

change for other phonemes or with

distortion; small opening of the mouth during

speech; imprecision or inefficacy of tongue

movements in isolated movements; the

tongue, when protruded, forming a heart in

its apex, with little protrusion capability, or

with protrusion bending its apex downward;

a tongue rest posture on the floor of the

mouth; difficulties of performing movements

with the tip of the tongue, such as licking ice

cream cone; history of difficulty to suckling

during breast-feeding; inefficient mastication

and deglutition with alteration for difficulty of

coupling the tongue in the hard palate.

The most frequent problem mentioned in the

literature related to an altered lingual

frenulum is speech production (Garcia-Pola

et all, 2002; Lee et all, 1989; Mukai et all,

1993; Velanovich, 1994; Wright, 1995;

Kotlow, 1999; Sanchez-Ruiz et all, 1999;

Messner et al, 2000 and 2002; Elias-

Podesta et all, 2001 & Lalakea et all, 2003).

Issues related to feeding, mainly during the breast-feeding phase, are the next most

frequently cited problem related to an

altered frenulum (Velanovich, 1994; Kotlow,

1999; Messner et all 2000; Elias-Podesta et

all, 2001; Berg, 1990; Marmet et all, 1990 &

Ballard et all 2002). These are followed by

problems with range of motion of the tongue

(Garcia-Pola et all, 2002; Wright, 1995;

Messner et al, 2000, 2002; Lalakea et all,

2003 & Defabianis, 2000); and deglutition

alterations (Wright, 1995; Kotlow, 1999 &

Sanches-Ruiz et all, 1999).

Various terms for and classifications of

lingual frenulum alterations are found in the

literature: tongue-tie, ankyloglossia,

hypertropic frenulum, thick frenulum,

muscular frenulum, fibrotic frenulum, and

frenulum with anterior insertion, short

frenulum and short frenulum with anterior

insertion (Kotlow, 1999; Singh & Kent, 2000;

Houaiss, 2001; Moore & Dalley, 2001 &

Marchesan, 2004). While many of

classifications address the form of the

frenulum, other characteristics are also

important. Singh and Kent (2000) describe

the lingual frenulum as a mucous membrane

fold that extends from the underside of the

tongue to the floor of the mouth. A large

median fold of mucous membrane cover

arises from the gingival on the lingual

surface of the tongue (Moore & Dalley, 2001). The foreshortened, small or absent

lingual frenulum characterizes

ankyloglossia. This can occur with full

fusion or partial fusion of the tongue with the

floor of the mouth.

Ankyloglossia is also characterized as the

tongue’s movement limited by a short or

absent lingual frenulum (Singh & Kent,

2000). Partial ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie,

is a congenital condition, the membrane

under the tongue is very short or its insertion

is very close to the tip of the tongue,

hindering the tongue’s protrusion (Berg,

1990). Ankyloglossia continues to be

defined as being a developmental anomaly,

characterized by short and thick lingual

frenulum resulting in limitations of tongue

movements (Garcia-Pola et all, 2002).

Some researchers have attempted to

differentiate and classify the frenulum. In

one study the lingual frenulum is

differentiated and classified according to:

short mucous membrane; mandibular insert

and hypertropic long mucous membrane

inserted into the crest of the alveolar edge

(Elias-Podesta et all, 2001). In another

study, the frenulum is classified as: short;

anterior insertion; and short with anterior

insertion (Marhesan, 2004). This

classification is similar to the

aforementioned definition, where the

tongue-tie or ankyloglossia is defined as a

short membrane, or inserted very close of

the tip of the tongue (Berg, 1990). These

classifications depend on the qualitative

criteria used, which is often fundamentally

based on the evaluator’s experience.

Few studies have been designed to quantify

the frenulum through direct measurements.

This may be due to the difficulty and

imprecision in measuring the soft tissues

involved. Only three studies have been

identified that used quantitative criteria to

measure and classify the lingual frenulum.

In the first study (Lee, Kim, & Lim, 1989) the

lingual frenulum was measured with a ruler

created for this purpose. The length of the

lingual frenulum was classified in the

following manner: average length of

frenulum with less than 10 mm - a mild

ankyloglossia; between 10 and 15 mm -

moderate; more than 15 mm (type-1) severe

ankyloglossia; and, a frenulum clinically considered as representing severe

ankyloglossia eventhough frenulum length

was less than 15-mm length (2 subjects

were classified as type-2 severe

ankyloglossia). The authors of this study

noted that the longer the frenulum, the more

anterior it would be inserted and the less the

mobility and autonomy of the tongue (Lee

et.al., 1989).

In the second study (Kotlow, 1990), the

individual was requested to protrude the

tongue out of the mouth as far as possible

while the length of the tongue was

measured using a ruler. The frenulum was

designated as clinically acceptable when

longer than 16 mm; Class I as medium

ankyloglossia of 12 to 16mm; Class II as

moderate ankyloglossia of 8 to 11 mm;

Class III as severe ankyloglossia of 3 to 7

mm; and Class IV or as full ankyloglossia if

smaller than 3 mm (Kotlow, 1990). In the

last study the authors used the Hazelbaker

(1993) scale for assessing the frenulum.

Criteria were developed with this scale to

observe the appearance and movements of

the tongue, as well as the elasticity and

insertion point of the frenulum. The length

of tongue’s frenulum was measured with the

tongue in an elevated position, with the

following measurements recorded: big,

small or equal to 1 cm (Ballard et all, 2002).

For this study, a normal frenulum insertion

was considered as approximately 1-cm from

the apex.

A review of the literature indicates that

disagreement persists among some health

professionals regarding how to classify the

frenulum as normal or altered. Differences

in clinical judgment also exist regarding the

indications for/against surgery. Due to the

variety of professional opinions regarding

surgical treatment of an altered lingual

frenulum, patients are often insecure or

confused about their options regarding

intervention. While a lingual frenulum may

be characterized as normal or altered

depending on the evaluation criteria used by

the evaluator, those classified as altered

may or may not be indicated for surgery. If

a uniform method of classification and

evaluation quantification and qualification

were developed, it should result in higher

examiner reliability and accuracy in

distinguishing between a normal and altered frenulum and more consistency in

recommendations for surgery. Accordingly

the purpose of this study was to develop a

method of differentiating between a normal

frenulum and an altered frenulum using

qualitative evaluation and numeric

quantification. This study aims, therefore, to

determine and report a quantitative method

to classify a lingual frenulum as either

normal or altered.

METHODS

98 subjects were enrolled in this research.

They were accompanied by a parent or

relative. They were patients of the Clinic -

School CEFAC’s. Authorization for the

subjects’ participation in the study was

obtained after they had been informed in

writing about the procedures and the

purpose of the research. The subjects

included in this study were 18 years of age

or older, were not receiving speech therapy,

did not have any temporomandibular joint

problems, had not previously had a lingual

frenectomy, had their central upper and

lower incisors, and did not have anterior

open bite.

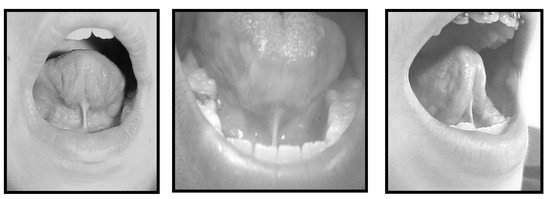

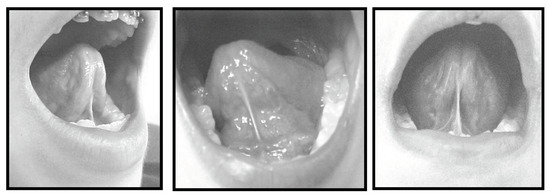

Two speech therapists evaluated the

frenulum and characterized it as normal or

altered using the qualitative protocol

proposed by Marchesan (2004) according to

the following criteria: a) short or smaller than

most frenulum, although inserted correctly

(Moore & Dalley, 2001) at the halfway back

area on the undersurface of the tongue and

extending to the floor of the mouth (Singh &

Kent, 2000) (Figure 1); b) with anterior

insertion, demonstrating normal size while

being inserted at any point forward from the

halfway area along the underside of the

tongue; it may be inserted close to the apex

(Figure 2); c) short with anterior insertion,

this being a mix of the previous two (Figure

3).

In addition to a qualitative evaluation, each

subject was requested to perform various

movements of the tongue to assess lingual

range of movement. The requested

movements were: protrude the tongue

outside the mouth; tongue moved laterally to

each labial commissure; and upward and

downward vertical movements of the tongue. Any difficulty with the requested movements resulted in the frenulum being

classified as altered.

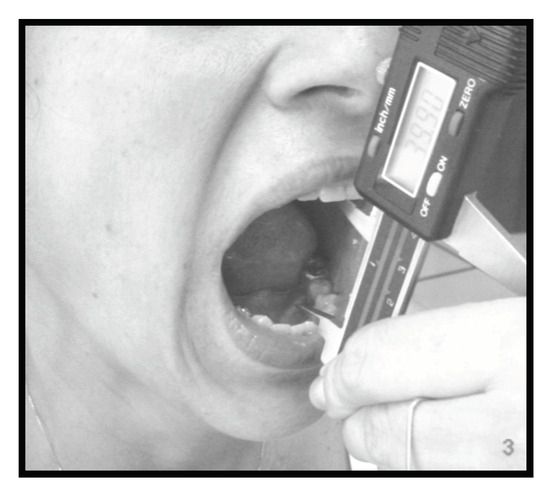

Following the classification of the frenulum

as normal or altered, four measurements

were obtained using the digital Starret slide

caliper. All measurements were taken by a

single speech therapist. The recorded

measurements included: a) maximum

mouth opening (with no tongue interference)

as measured at the incisal edges of the left

upper and lower central incisors. This

measurement served as a reference support

point for the slide caliper (Figure 4), and was

taken as an absolute value reference for

subsequent comparison with other

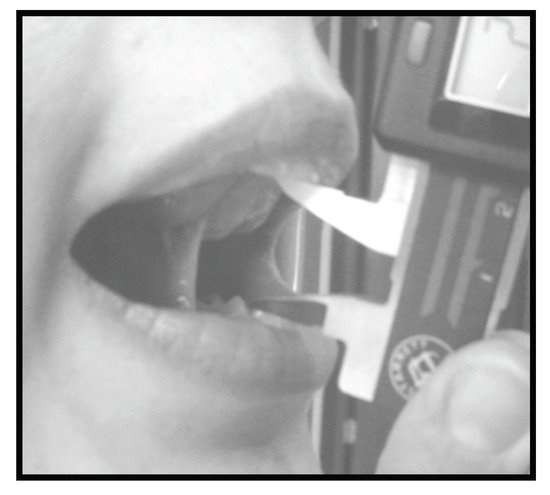

measurements; b) for the second

measurement each subject was requested

to put the apex of his/her tongue on the

palatine (incisal) papilla, maintaining this

posture with the mouth open maximally and

with the support points for the slide caliper

maintained at the left central incisors (Figure

5); c) the third measurement was obtained

while the subject created a negative

pressure by sucking the tongue against the

hard palate area, maintaining this position

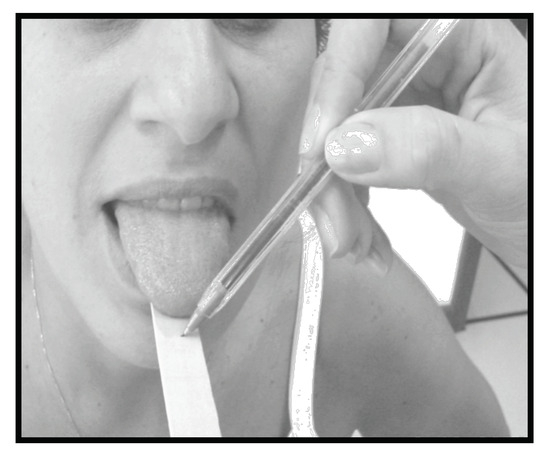

with the mouth open (Figure 6); d) the last

measurement was taken while each subject

protruded the tongue and stretched it

maximally over a wooden spatula held by

the examiner at the lower incisors (Figure 7).

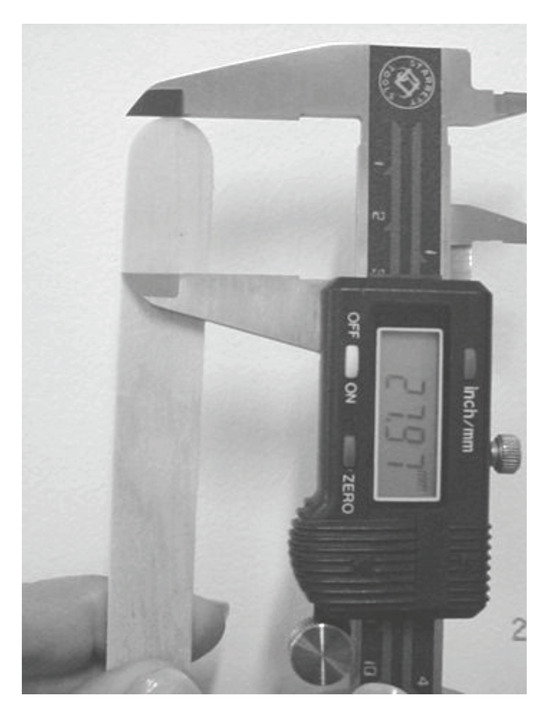

A mark made with a black pencil was

recorded on the spatula at the place of the

longest measurement of the tongue. Using

the slide caliper, this measurement, from the

tip of the spatula to the place where the

tongue had reached in extension was

measured (Figure 8). All measurements

were logged onto a previously designed

table consisting of the following data: initials

of subject’s name and age, collection date,

classification of frenulum as normal or

altered, the measurements taken at full

mouth opening, tongue on the papilla,

tongue sucked against the hard palate, and

tongue on the spatula. The rule of three

was applied, comparing the wide-open

mouth reference valus with each of the other

three measurements. The data were

collected between the months - August 2002

to December 2003.

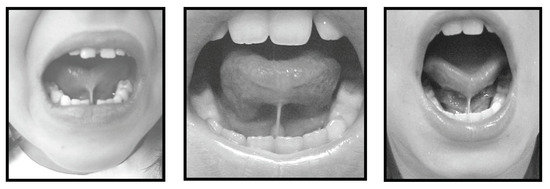

Figure 1.

Short Frenulum.

Figure 2.

Frenulum with Anterior Insertion.

Figure 3.

Frenulum with Anterior Insertion and Short.

Figure 4.

Full Mouth Opening.

Figure 5.

Tongue on the Papilla.

Figure 6.

Tongue Suctioned on the Hard Palate.

Figure 7.

Tongue on the Spatula.

Figure 8.

Measuring the Spatula.

The Mann-Whitney U test was adopted as the

statistical instrument to evaluate differences among the normal and altered

groups. 5% (0.050)

significance level was adopted for statistical tests. This research was

approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research under Nº. 100/03. It was

considered without risk, but informed written consent was necessary.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the comparison data for the 98 subjects. For the open mouth task there was no significant difference

among the medians of the frenulum (p>0.05). For the normal frenulum, the median of the tongue on the papilla (33.2),

the median of the tongue sucked against the hard palate (27.1), and tongue on the spatula (29.9) was larger than for the altered group, 27.7; 25.1 and 26.2 respectively. These findings were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Distribution of 98 cases above 18 years old in relation with the normal frenulum versus altered frenulum.

Table 2 displays the distribution of differences among the tongue measurements on the incisal papilla and wide-open mouth with relation to the normal versus altered frenulum in the 98 adults subjects. The differences in the measurements were significantally larger among the altered frenulum group. The median of the difference between wide-open mouth and mouth open with the tongue on the papilla was 12.2 for normal frenulum and 21 for altered frenulum. Also, the median of the difference between wide-open mouth and tongue on the papilla was 13.4 (6.1) and for altered frenulum 19.4 (7.7).

Table 2.

- Distribution of the differences among the tongue measurements on the papilla and open mouth with relation to the normal frenulum versus altered frenulum of all the 98 adults older than 18 years.

DISCUSSION

After the measurement phase of the study was completed, from the examiner’s point of view, the more-easily obtained measurement was with the tongue on the incisal papilla. It was possible to obtain this measurement with any type of frenulum alteration. The measurement obtained with the tongue sucked onto the hard palate by negative pressure is difficult to obtain, since few subjects were able to maintain this posture while the measurement was taken. The posture of the tongue required for this measurement was particularly difficult to maintain in subjects with a short frenulum, especially for subjects with short frenulum who also had an anterior attachment.

The measurement of the tongue on the spatula in subjects whose frenulum had severe anterior insertion was much lower when compared with the wide-open mouth. However, in the subjects with a short frenulum that attached posteriorly on the undersurface of the tongue, which allowed freedom in the anterior portion of the tongue, little measurement differences were found when compared with the wide-open mouth measurement. For subjects with a short frenulum or with slight anterior insertion, no significant differences were identified, while in normal subjects there were relevant differences. While measurements for tongue protrusion are easily collected, this measurement condition is not considered to be critical in the comparison and differentiation between a normal and altered frenulum. In contrast, it seems important to point out that the significant difference between the measurement of the tongue on the incisal papilla and the measurement for the open mouth has the most potential for differentiating between a normal and altered frenulum, with a 33.2 median for a normal frenulum and of 27.7. for an altered frenulum.

The findings submitted in Table 1 indicate that there is no statistical difference (p = 0.6071) among subjects with either a normal frenulum (46.0) for the open mouth measurements or an altered frenulum (47.2 median). Accordingly, this measurement can be considered as absolute value and can serve as a reference for other measures of the frenulum.

The quantitative classifications found in the three unique studies mentioned in the literature (Lee et al, 1989; Kotlow, 1999 &

Ballard et al, 2002)) used frenulum measuring forms that differ from those used in this study. For this reason, it is not possible to compare the data with these studies.

To facilitate the physician’s analysis of the frenulum, the percentages of all sampled subjects were calculated by dividing the measurement of the tongue on the incisal papilla by the measurement obtained with the wide-open mouth. It was determined that for the subjects whose frenulum had been classified as normal, a percentage above approximately 60% was found, while, for subjects whose frenulum had been classified as altered, a percentage around 50% or less was obtained.

There is obviously no measurement (percentile) that can be strictly adopted that clearly designates a frenulum as normal or altered, because some normal subjects, although few, also showed a value below 50%, while some subjects with altered frenulum showed values above 50%. This variation may have occurred due to a lack of differentiation of the data for the group with an altered frenulum when compared with the data for the group with normal frenulum.

All subjects with an altered frenulum were grouped together for statistical purposes, and treated as a single group. It was noted that for the subjects with altered frenulum with anterior insertion, the percentage with mouth fully open, compared with mouth open with tongue on the papilla was above 50%. Even though this occurred with few subjects it should be considered. A trend was identified that subjects with an altered frenulum had low percentile values, while normal subjects, tended to have higher percentile values when comparing relationships between the wide-open mouth measurements with those of the tongue on the incisal papilla.

Based on the results of this study, it can be infered that the smaller the relationship between the measurement of the tongue on the incisal papilla and the measurement of mouth opening, the larger the chance that the frenulum is altered. There is no value in making a recommendation for surgery based only on a calculated figure. An appropriate suggestion based on the data in this study is that quantitative data should be analyzed together with the qualitative data in evaluating the normal or altered state of a lingual frenulum. For this purpose, use one of the frenulum classifications proposed in the literature (Garcia-Pola et all, 2002; Elias-

Podesta et all, 2001;; Berg, 1990; Singh & Kent, 2000; Marchesan, 2004 & Halzebaker,

1993).

Additional research should be conducted to increase the precision criteria for measuring the lingual frenulum. As a limiting factor, it should be noted that such measurements are of soft tissue structures which can possess a great degree of variation. Depending on the place of contact for tongue support with maximal opening of the mouth, and while attempting to sustain a specific posture of the tongue during the measurement, subject performances may show differing numerical values in repeated measures.

The data obtained with the classification of a frenulum, when using qualitative or quantitative classifications, or both, should always be analyzed together with the clinical history and with the data found in the clinical examination.

It is hoped that this study may aid other health professionals in evaluating weather a lingual frenulum is normal or altered. Additional research is needed to fully identify all the pertinent factors and variations that may be found when assessing a lingual frenum.

CONCLUSION

The comparison of the values obtained with the measurement of the mouth maximally open with the values found when the mouth is open with the tongue tip touching the incisal papilla, seems to be a viable clinical tool for determining whether a lingual frenulum is normal or altered.

References

- Ballard, J. L., C. E. Auer, and J. C. Khoury. 2002. Ankyloglossia: Assessment, incidence, and effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics 110: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, K. L. 1990. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) and breastfeeding: A review. Journal Human Lactent 6: 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defabianis, P. 2000. Ankyloglossia and its influence on maxillary and mandibular development. (A seven-year follow-up case report). Function. Orthodontic 17: 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elias-Podesta, M. C., M Seclén-Nunez del Arco, P. G. Tello-Meléndez, and B. A. Cháves-González. 2001. Diagnóstico clínico de anquiloglosia, posibles complicaciones y propuesta de solución quirúrgica. Revista Odontologica 3: 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pola, M. J., J. M. Garcia-Martin, and M. Gonzalez-Garcia. 2002. Prevalence of oral lesions in the 6 years-old pediatric population of Oviedo (Spain). Medicina Oral 7: 184–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halzelbaker, A. K. 1993. The assessment tool for lingual frenulum function (ATLFF): Use in a lactation consultant private practice . Ph. D. Thesis, Pasadena, CA. Pacific Oaks College. [Google Scholar]

- Houaiss, A. 2001. Dicionário da língua portuguesa. Objetiva. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlow, L. A. 1999. Ankyloglossia (tongue-tie): A diagnostic and treatment quandary. Quintessence International 30: 259–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lalakea, M. L., and A. H. Messner. 2003. Ankyloglossia: The adolescent and adult perspective. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 128: 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. K., Y. S. Kim, and C. Y. Lim. 1989. A pathological consideration of ankyloglossia and lingual myoplasty. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa hyophoe Chi 27: 287–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchesan, I. Q. 2004. Lingual frenulum: Classification and speech interference. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 30: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmet, C., E. Shell, and R. Marmet. 1990. Neonatal frenotomy may be necessary to correct breastfeeding problems. Journal Human Lactent 6: 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, A. H., M. L. Lalakea, J. Aby, J. MacMahon, and E. Bair. 2000. Ankyloglossia incidence and associated feeding difficulties. Archives Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery 126: 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, A. H., and M. L. Lalakea. 2002. The effect of ankyloglossia on speech in children. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 127: 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K. L., and A. F. Dalley. 2001. Anatomia orientada para a clínica, 4th ed. Guanabara Koogan. [Google Scholar]

- Mukai, S., C. Mukai, and K. Asaoka. 1993. Congenital ankyloglossia with deviation of the epiglottis and larynx: Symptoms and respiratory function in adults. Annals Otology Rhinology Laryngology 102: 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches-Ruiz, I., G. Gonzalez-Landa, V. Perez-González, L. Sanchez-Fernández, C. Prado-Fernández, and I. Azcona-Zorrilla. 1999. Section of the sublingual frenulum: Are the indications correct? Cirurgia Pediatrica 12: 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., and R. D. Kent. 2000. Dictionary of speech-language pathology. Singular. [Google Scholar]

- Velanovich, V. 1994. The transverse-vertical frenuloplasty for ankyloglossia. Mil. Medicine 159: 714–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. E. 1995. Tongue-tie. Journal Pediatric Child Health 31: 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2008 by the authors. 2008 Irene Queiroz Marchesan