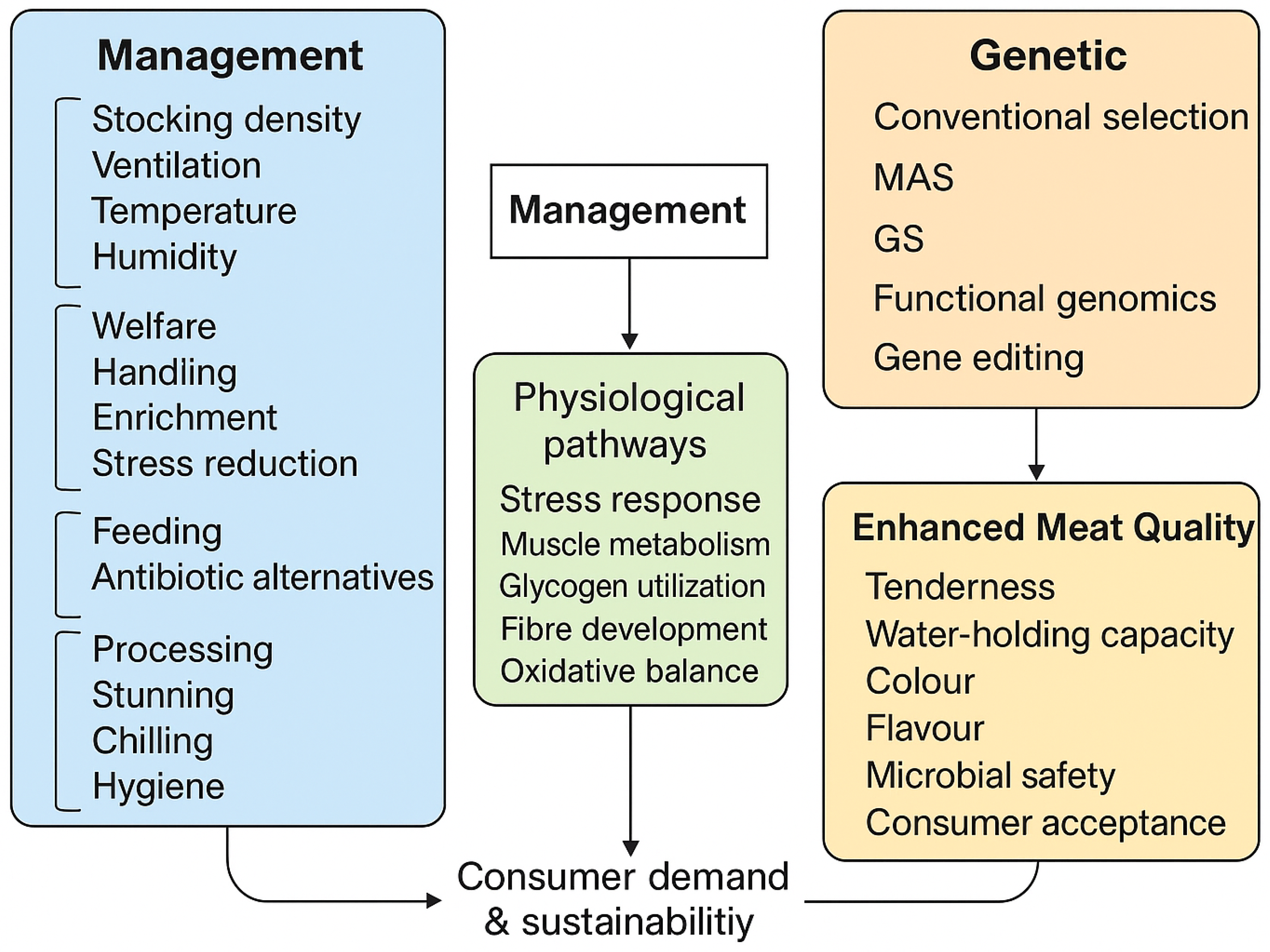

Management and Genetics Approaches for Enhancing Meat Quality in Poultry Production Systems: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Management Approaches

2.1. Rearing Conditions and Stocking Density

2.2. Antibiotics and Alternatives

2.3. Husbandry and Welfare Practices

2.4. Processing Innovations

2.5. HACCP and Hygiene Management

2.6. Technological Trends and Future Outlook

3. Genetic Approaches

3.1. Historical Context and the Shift Toward Quality

3.2. Understanding the Genetic Basis of Meat Quality Traits

3.3. Conventional Breeding and Selection Programs

3.4. Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS)

3.5. Genomic Selection (GS)

3.6. Functional Genomics and Gene Expression

3.7. Transgenic and Gene Editing Technologies

3.8. Balancing Quality with Performance and Welfare

3.9. Commercial Applications

3.10. Integrated Strategies for Synergizing Management and Genetic Interventions

3.11. Challenges and Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mueller, A.J.; Maynard, C.J.; Jackson, A.R.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Kidd, M.T.; Rochell, S.J.; Caldas-Cueva, J.P.; Sun, X.; Giampietro-Ganeco, A.; Owens, C.M. Assessment of Meat Quality Attributes of Four Commercial Broiler Strains Processed at Various Market Weights. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, N.A.; Rafiq, A.; Kumar, F.; Singh, V.; Shukla, V. Determinants of Broiler Chicken Meat Quality and Factors Affecting Them: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2997–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kong, B.; Bowker, B.C.; Zhuang, H.; Kim, W.K. Nutritional Strategies to Improve Meat Quality and Composition in the Challenging Conditions of Broiler Production: A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracci, M.; Estévez, M. (Eds.) Burleigh Dodds series in agricultural science. In Improving Poultry Meat Quality; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-28683-7. [Google Scholar]

- Petracci, M.; Mudalal, S.; Soglia, F.; Cavani, C. Meat Quality in Fast-Growing Broiler Chickens. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2015, 71, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Watcharaanantapong, P.; Yang, X.; Thornton, T.; Gan, H.; Tabler, T.; Prado, M.; Zhao, Y. Evaluating Broiler Welfare and Behavior as Affected by Growth Rate and Stocking Density. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Marmion, M.; Ferone, M.; Wall, P.; Scannell, A.G.M. On Farm Interventions to Minimise Campylobacter Spp. Contamination in Chicken. Br. Poult. Sci. 2021, 62, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabir, M.; Miah, M.; Alam, M.; Bhuiyan, M.; Haque, M.; Sujan, K.; Mustari, A. Impacts of Stocking Density Rates on Welfare, Growth, and Hemato-Biochemical Profile in Broiler Chickens. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, R.M.; Hassan, F.; Farag, M.R.; Nasir, T.A.; Ragni, M.; Mahgoub, H.A.M.; Alagawany, M. Thermal Stress and High Stocking Densities in Poultry Farms: Potential Effects and Mitigation Strategies. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 99, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasr, M.A.F.; Alkhedaide, A.Q.; Ramadan, A.A.I.; Hafez, A.E.S.E.; Hussein, M.A. Potential Impact of Stocking Density on Growth, Carcass Traits, Indicators of Biochemical and Oxidative Stress and Meat Quality of Different Broiler Breeds. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Hong, E.-C.; Kang, H.-K. Effects of Stocking Density on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Status, and Meat Quality of Finisher Broiler Chickens under High Temperature. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbut, S.; Leishman, E.M. Quality and Processability of Modern Poultry Meat. Animals 2022, 12, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, R.K.; Abrahimkhil, M.A.; Rahimi, N.; Banuree, S.Z.; Banuree, S.A.H. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Vitamin E on Growth Performance and Immune System of Broiler Chickens. J. World’s Poult. Res. 2023, 208, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, I.C.; Gunnink, H.; van Harn, J. Wet Litter Not Only Induces Footpad Dermatitis but Also Reduces Overall Welfare, Technical Performance, and Carcass Yield in Broiler Chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2014, 23, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Zulkifili, I.; Islam, S.; Awad, E. Effect of Wood Shaving Litter Density on the Growth, Leg Disorders and Manurial Value in Broiler. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 47, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunitasari, F.; Jayanegara, A.; Ulupi, N. Performance, Egg Quality, and Immunity of Laying Hens Due to Natural Carotenoid Supplementation: A Meta-Analysis. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2022, 43, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussaada, T.; Lakhdari, K.; Benatallah, S.A.; Meradi, S. Effects of Common Litter Types and Their Physicochemical Properties on the Welfare of Broilers. Vet. World 2022, 15, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirri, F.; Minelli, G.; Folegatti, E.; Lolli, S.; Meluzzi, A. Foot Dermatitis and Productive Traits in Broiler Chickens Kept with Different Stocking Densities, Litter Types and Light Regimen. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 6, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shynkaruk, T.; Long, K.; Leblanc, C.A.; Schwean-Lardner, K. Impact of Stocking Density on the Welfare and Productivity of Broiler Chickens Reared to 34 d of Age. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, O.W.; Miller, S.P.; Wood, B.J. Aspects of Selection for Feed Efficiency in Meat Producing Poultry. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2013, 69, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, B.M.; Anderson, K.A.; Oviedo-Rondón, E.O.; Livingtson, K.; Grimes, J.L. Effects of Stocking Density on Large White, Commercial Tom Turkeys Reared to 20 Weeks of Age: 1. Growth and Performance. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5582–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purswell, J.L.; Olanrewaju, H.A.; Zhao, Y. Effect of Feeder Space on Live Performance and Processing Yields of Broiler Chickens Reared to 56 Days of Age. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2021, 30, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, M.; Sarmiento-Franco, L.; Santos-Ricalde, R.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A. Poultry Meat Production in Free-Range Systems: Perspectives for Tropical Areas. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, D.; Kim, J.H.; Park, G.H.; Delos Reyes, J.B.; Kil, D.Y. Effect of Heat Stress and Stocking Density on Growth Performance, Breast Meat Quality, and Intestinal Barrier Function in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2019, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.; Sah, N.; Singh, A.K.; Lee, C.N.; Jha, R.; Mishra, B. Dietary Supplementation of Dried Plum: A Novel Strategy to Mitigate Heat Stress in Broiler Chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A. Heat Stress Management in Poultry. Anim. Physiol. Nutr. 2021, 105, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onagbesan, O.M.; Uyanga, V.A.; Oso, O.; Tona, K.; Oke, O.E. Alleviating Heat Stress Effects in Poultry: Updates on Methods and Mechanisms of Actions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1255520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornescu, G.M.; Panaite, T.D.; Untea, A.E.; Varzaru, I.; Saracila, M.; Dumitru, M.; Vlaicu, P.A.; Gavris, T. Mitigation of Heat Stress Effects on Laying Hens’ Performances, Egg Quality, and Some Blood Parameters by Adding Dietary Zinc-Enriched Yeasts, Parsley, and Their Combination. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1202058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasti, S.; Sah, N.; Mishra, B. Impact of Heat Stress on Poultry Health and Performances, and Potential Mitigation Strategies. Animals 2020, 10, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boushy, A.R.E.; van Marle, A.L. The Effect of Climate on Poultry Physiology in Tropics and Their Improvement. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 1978, 34, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.B.; Pandorfi, H.; Rabello, C.B.-V.; da Silva, E.P.; Torres, T.R.; Santos, P.A.; Morril, W.B.; Duarte, N.M. Performance of Free-Range Chickens Reared in Production Modules Enriched with Shade Net and Perches. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2014, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, A.R.; Lefferts, L.Y.; McKenzie, S.; Walker, P. What Do We Feed to Food-Production Animals? A Review of Animal Feed Ingredients and Their Potential Impacts on Human Health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Mishra, P. Dietary Fiber in Poultry Nutrition and Their Effects on Nutrient Utilization, Performance, Gut Health, and on the Environment: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, S.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Sifri, M.; Selvaraj, R. Yeasts and Yeast-Based Products in Poultry Nutrition. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lee, K.; Kim, I.H. Optimizing Finishing Pig Performance and Sustainability: The Role of Protein Levels and Eco-Friendly Additive. Animals 2025, 15, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraja, D.; Malathi, V.; Naik, J.; Indresh, H.C.; Sreedhara, J.N. Effect of Butyric Acid Supplementation on Growth Performance and Immune Response in Broilers. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 2422–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, A.B.; Whyte, P.; Bolton, D.J.; Tiwari, B.K. Strategies and Novel Technologies to Control Campylobacter in the Poultry Chain: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1353–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, Y.T.; Savini, F.; Indio, V.; Seguino, A.; Giacometti, F.; Serraino, A.; Candela, M.; De Cesare, A. Systematic Review on Microbiome-Related Nutritional Interventions Interfering with the Colonization of Foodborne Pathogens in Broiler Gut to Prevent Contamination of Poultry Meat. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Moore, R.J.; Stanley, D.; Chousalkar, K.K. The Gut Microbiota of Laying Hens and Its Manipulation with Prebiotics and Probiotics To Enhance Gut Health and Food Safety. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00600-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madlala, T.; Okpeku, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Understanding the Interactions between Eimeria Infection and Gut Microbiota, towards the Control of Chicken Coccidiosis: A Review. Parasite 2021, 28, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, K.; Konkol, D.; Korczyński, M. Overview of the Use of Probiotics in Poultry Production. Animals 2021, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.H.; Ashrafudoulla, M.; Mevo, S.I.U.; Mizan, M.F.R.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S. Current and Future Interventions for Improving Poultry Health and Poultry Food Safety and Security: A Comprehensive Review. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2023, 22, 1555–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basnet, J.; Eissa, M.A.; Cardozo, L.L.Y.; Romero, D.G.; Rezq, S. Impact of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Gut Microbiome and Hormonal Regulation. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shehata, A.M.; Arif, M.; Paswan, V.K.; Batiha, G.E.-S.; Khafaga, A.F.; Elbestawy, A.R. Approaches to Prevent and Control Campylobacter Spp. Colonization in Broiler Chickens: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 4989–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N.; Hermoso, M.A.; Gotteland, M. Butyrate and the Fine-Tuning of Colonic Homeostasis: Implication for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiuolo, J.; Bulotta, R.M.; Ruga, S.; Nucera, S.; Macrì, R.; Scarano, F.; Oppedisano, F.; Carresi, C.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; et al. The Postbiotic Properties of Butyrate in the Modulation of the Gut Microbiota: The Potential of Its Combination with Polyphenols and Dietary Fibers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Gaur, P.; Leal, É.; Lyu, X.; Ahmad, S.; Puri, P.; Chang, C.-M.; Raj, V.S.; Pandey, R.P. Unveiling Roles of Beneficial Gut Bacteria and Optimal Diets for Health. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1527755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Bourassa, D. Probiotics in Poultry: Unlocking Productivity Through Microbiome Modulation and Gut Health. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashtetsky, V.; Ostapchuk, P.; Kuevda, T.; Zubochenko, D.; Yemelianov, S.; Uppe, V. Use of Phytobiotics in Animal Husbandry and Poultry. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 215, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.E.; Shehata, A.M.; Alzahrani, S.O.; Shafi, M.E.; Mesalam, N.M.; Taha, A.E.; Swelum, A.A.; Arif, M.; Fayyaz, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E. The Role of Polyphenols in Poultry Nutrition. Anim. Physiol. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1851–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze, M. Phytobiotics, a Natural Growth Promoter for Poultry. In Veterinary Medicine and Science; Babinszky, L., Oliveira, J., Mauro Santos, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Volume 8, ISBN 978-1-83969-403-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alem, W.T. Effect of Herbal Extracts in Animal Nutrition as Feed Additives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminullah, N.; Mostamand, A.; Zahir, A.; Mahaq, O.; Azizi, M.N. Phytogenic Feed Additives as Alternatives to Antibiotics in Poultry Production: A Review. Vet. World 2025, 18, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-García, A.A.; Pardío-Sedas, V.T.; León-Banda, G.G.; Ahuja-Aguirre, C.; Paredes-Ramos, P.; Hernández-Cruz, B.C.; Murillo, V.V. Effect of Stress during Slaughter on Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality in Tropical Beef Cattle. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, E.M.C.; Picard, B.; Deiss, V.; Berri, C.; Hocquette, J.-F.; Lebret, B.; Lefèvre, F.; Hamill, R.; Gagaoua, M. Understanding the Determination of Meat Quality Using Biochemical Characteristics of the Muscle: Stress at Slaughter and Other Missing Keys. Foods 2021, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Mahmood, M.; Yar, M.K.; Bakhsh, M.; Ullah, S. Effect of On- and off-Farm Factors on Animal Stress and Meat Quality Characteristics. In Animal Husbandry; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyimba, F.; Hartson, S.D.; Rogers, J.; VanOverbeke, D.L.; Mafi, G.G.; Ramanathan, R. Changes in Glycolytic and Mitochondrial Protein Profiles Regulates Postmortem Muscle Acidification and Oxygen Consumption in Dark-Cutting Beef. J. Proteom. 2020, 232, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Zhang, L.; Lin, S. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Impact of Muscle Fiber Types on Meat Quality in Livestock and Poultry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1284551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, S.K.; Silva, S.; Gerrard, D.E. New Insights in Muscle Biology That Alter Meat Quality. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.-W. The Impact of Temperature and Humidity on the Performance and Physiology of Laying Hens. Animals 2020, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, J.-R.; Preynat, A.; Cozannet, P.; Briens, M.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Greene, E.S.; Owens, C.M.; Dridi, S.; Rochell, S.J. Constant and Cyclic Chronic Heat Stress Models Differentially Influence Growth Performance, Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Rathore, G.; Joshi, M. Impact of Climate Change on Animal Health and Mitigation Strategies: A Review. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2024, 10, 18805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, C.-M.; Dunlop, M.W. Review of Litter Turning during a Grow-out as a Litter Management Practice to Achieve Dry and Friable Litter in Poultry Production. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lin, X.; Qing, K.; Zhou, X.; Luo, Z. The Effects of Ventilation, Humidity, and Temperature on Bacterial Growth and Bacterial Genera Distribution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C.; Singh, J. Impact of Ammonia and Humidity on Poultry. Available online: https://www.poultrytrends.in/impact-of-ammonia-and-humidity-on-poultry/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Tabler, T. Managing Litter Moisture in Broiler Houses with Built-Up Litter; Mississipi Sate University: Starkville, MS, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tabler, T. Managing Heat and Minimum Ventilation Systems in the Broiler House; Mississipi Sate University: Starkville, MS, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenga, M.; Nääs, I.; Lima, N.; Carvalho-Curi, T.; Reis, J. Optimization Algorithm Applied to Environmental Control in Broiler Houses. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2020, 22, eRBCA-2020-1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.V.S.; De Moura, D.J.; Estellés, F.; Ramón-Moragues, A.; Calvet, S.; Villagrá, A. Assessment of Husbandry Practices That Can Reduce the Negative Effects of Exposure to Low Ammonia Concentrations in Broiler Houses. Animals 2022, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, E.E.; Lorenzoni, G. Key Aspects of Inlets for Mechanical Ventilation of Poultry Housing. Code: ART-5670; The Pennsylvania State University: Starkville, MS, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ricke, S.C. Strategies to Improve Poultry Food Safety, a Landscape Review. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Qiao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Pan, H. Correlation Analysis of Muscle Amino Acid Deposition and Gut Microbiota Profile of Broilers Reared at Different Ambient Temperatures. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 34, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, B.M.R.; Shynkaruk, T.; Crowe, T.G.; Fancher, B.I.; French, N.; Gillingham, S.; Schwean-Lardner, K. Does Light Color during Brooding and Rearing Impact Broiler Productivity? Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, B.M.R.; Shynkaruk, T.; Crowe, T.G.; Fancher, B.I.; French, N.; Gillingham, S.; Schwean-Lardner, K. Light Color and the Commercial Broiler: Effect on Behavior, Fear, and Stress. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Rethinking Poultry Welfare—Integrating Behavioral Science and Digital Innovations for Enhanced Animal Well-Being. Poultry 2025, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, A.; Oyakawa, C.; Yoshihara, Y.; Ninomiya, S.; Sato, S. Effect of Environmental Enrichment on the Behavior and Welfare of Japanese Broilers at a Commercial Farm. J. Poult. Sci. 2015, 52, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.; Blatchford, R.A.; de Jong, I.C.; Erasmus, M.A.; Levengood, M.; Newberry, R.C.; Regmi, P.; Riber, A.B.; Weimer, S. Enhancing Their Quality of Life: Environmental Enrichment for Poultry. Poult. Sci. 2022, 102, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracci, M.; Cavani, C. Muscle Growth and Poultry Meat Quality Issues. Nutrients 2011, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, S. Future of Broiler Farming: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities. In Agricultural Sciences; Al-Marzooqi, W., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; Volume 14, ISBN 978-0-85466-011-7. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.P. Poultry Processing and Products. In Food Processing; Clark, S., Jung, S., Lamsal, B., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 549–566. ISBN 978-0-470-67114-6. [Google Scholar]

- Faucitano, L. Preslaughter Handling Practices and Their Effects on Animal Welfare and Pork Quality1. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellozza, B.I.; Marques, R.S. Effects of Pre-Slaughter Stress on Meat Characteristics and Consumer Experience. In Meat and Nutrition; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Debut, M.; Berri, C.; Baeza, E.; Sellier, N.; Arnould, C.; Guemene, D.; Jehl, N.; Boutten, B.; Jego, Y.; Beaumont, C.; et al. Variation of Chicken Technological Meat Quality in Relation to Genotype and Preslaughter Stress Conditions. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yue, H.; Zhang, H.J.; Xu, L.; Wu, S.; Yan, H.; Gong, Y.-X.; Qi, G. Transport Stress in Broilers: I. Blood Metabolism, Glycolytic Potential, and Meat Quality. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 2033–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarpajouh, S. Low-Stress Handling Ensures Good Quality Broiler Meat. Available online: https://www.poultryworld.net/the-industrymarkets/processing/low-stress-handling-ensures-good-quality-broiler-meat/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Vogel, K.D.; Romans, E.F.I.; Kirk, A.A.; Obiols, P.L.; Velarde, A. Stress Physiology of Animals During Transport. In Livestock Handling and Transport; Grandin, T., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2024; pp. 34–67. ISBN 978-1-80062-511-2. [Google Scholar]

- Prates, J.A.M. Enhancing Meat Quality and Nutritional Value in Monogastric Livestock Using Sustainable Novel Feed Ingredients. Foods 2025, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T. Livestock Handling at the Abattoir: Effects on Welfare and Meat Quality. Meat Muscle Biol. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaw, A.B.; Muhammed, T.S. Meat Quality and Carcass Characteristics Assessments in Broiler Chickens Subjected to Different Pre-Slaughter Feed Withdrawal Times. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 761, p. 12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncho, C.M.; Berdos, J.I.; Gupta, V.; Rahman, A.; Mekonnen, K.T.; Bakhsh, A. Abiotic Stressors in Poultry Production: A Comprehensive Review. Anim. Physiol. Nutr. 2025, 109, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.N.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Kaka, U.; Rukayadi, Y.; Kadir, M.Z.A.A.; Radzi, M.A.M.; Kumar, P.; Nurulmahbub, N.A.; Sazili, A.Q. Assessing Meat Quality and Textural Properties of Broiler Chickens: The Impact of Voltage and Frequency in Reversible Electrical Water-Bath Stunning. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbut, S. Past and Future of Poultry Meat Harvesting Technologies. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.; Schilling, M.W.; Williams, J.B.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Battula, V.; Christensen, K.B.; Vizzier-Thaxton, Y.; Schmidt, T.B. Broiler Stunning Methods and Their Effects on Welfare, Rigor Mortis, and Meat Quality. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2013, 69, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, E.; Segerkvist, K.A.; Karlsson, A.; Ólafsdóttir, A.; Hilmarsson, Ó.Þ.; Guðjónsdóttir, M.; Þorkelsson, G. A Comparison of Two Different Slaughter Systems for Lambs. Effects on Carcass Characteristics, Technological Meat Quality and Sensory Attributes. Animals 2021, 11, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savell, J.W.; Mueller, S.L.; Baird, B.E. The Chilling of Carcasses. Meat Sci. 2005, 70, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savenije, B.; Schreurs, F.J.G.; Winkelman-Goedhart, H.A.; Gerritzen, M.A.; Korf, J.; Lambooij, E. Effects of Feed Deprivation and Electrical, Gas, and Captive Needle Stunning on Early Postmortem Muscle Metabolism and Subsequent Meat Quality. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalginbayev, D.B.; Uazhanova, R.U.; Antipova, L.V.; Baibatyrov, T.A. Study of Sensory Characteristics of Poultry Meat Obtained With the Use of Modern Stunning Technology. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 994, p. 12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yan, C.; Descovich, K.; Phillips, C.J.C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. The Effects of Preslaughter Electrical Stunning on Serum Cortisol and Meat Quality Parameters of a Slow-Growing Chinese Chicken Breed. Animals 2022, 12, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.; Raj, M. A Review of Different Stunning Methods for Poultry—Animal Welfare Aspects (Stunning Methods for Poultry). Animals 2015, 5, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSIS. HACCP Guidance; Food Safety and Inspection Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.fsis.usda.gov/inspection/compliance-guidance/haccp (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Wierup, M. The Importance of Hazard Analysis by Critical Control Point for Effective Pathogen Control in Animal Feed: Assessment of Salmonella Control in Feed Production in Sweden, 1982–2005. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lv, E.; Lu, H.; Guo, J. Experimental Analysis of a Spray Hydrocooler with Cold Energy Storage for Litchi. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.; Maharjan, P.; Fouladkhah, A.C. Practical Preventive Considerations for Reducing the Public Health Burden of Poultry-Related Salmonellosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støier, S.; Larsen, H.D.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Lykke, L. Improved Animal Welfare, the Right Technology and Increased Business. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilev, D.; Stajković, S.; Karabasil, N.; Dimitrijević, M.; Teodorović, V. Perspectives in Meat Processing. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 333, p. 12024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.N.; Kumar, P.; Sazili, A.Q. Are Spiritual, Ethical, and Eating Qualities of Poultry Meat Influenced by Current and Frequency during Electrical Water Bath Stunning? Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomović, V.; Petrović, L.; Džinić, N. Effects of Rapid Chilling of Carcasses and Time of Deboning on Weight Loss and Technological Quality of Pork Semimembranosus Muscle. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickelson, M.A.; Warner, R.D.; Seman, D.L.; Crump, P.M.; Claus, J. Carcass Chilling Method and Electrical Stimulation Effects on Meat Quality and Color in Lamb. Meat Muscle Biol. 2018, 2, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcutt, J.K.; Russell, S.M. General Guidelines for Implementation of HACCP in a Poultry Processing Plant; The University of Georgia: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Suherman, S.; Janitra, A.A.; Budhiary, K.N.S.; Pratiwi, W.; Idris, F. Review on Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) in the Dairy Product: Cheese. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1053, p. 12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nganje, W.E.; Burbidge, L.D.; Denkyirah, E.K.; Ndembe, E. Predicting Food-Safety Risk and Determining Cost-Effective Risk-Reduction Strategies. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkin, R.B. The Use of HACCP in the Production of Meat and Poultry Products. J. Food Prot. 1990, 53, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdokhina, S.I. Process Approach in Integrated Quality and Safety Management System for Poultry Products. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 315, p. 22050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanitation Performance Standards. In Handbook of Meat and Meat Processing; Hui, Y.H., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 734–759. ISBN 978-0-429-15146-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ryther, R. Food Technologies: Cleaning and Disinfection Technologies (Clean-In-Place, Clean-Out-of-Place). Encycl. Food Saf. 2014, 3, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, R. Current and Future Technologies for the Decontamination of Carcasses and Fresh Meat. Meat Sci. 2002, 62, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Rama, E.N.; Kataria, J.M.; Leone, C.; Thippareddi, H. Emerging Meat Processing Technologies for Microbiological Safety of Meat and Meat Products. Meat Muscle Biol. 2020, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebezov, M.; Farhan Jahangir Chughtai, M.; Mehmood, T.; Khaliq, A.; Tanweer, S.; Semenova, A.; Khayrullin, M.; Dydykin, A.; Burlankov, S.; Thiruvengadam, M.; et al. Novel Techniques for Microbiological Safety in Meat and Fish Industries. Appl. Sci. 2021, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Spachos, P.; Pensini, E.; Plataniotis, K.N. Deep Learning and Machine Vision for Food Processing: A Survey. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curti, P.D.F.; Selli, A.; Pinto, D.L.; Merlos-Ruiz, A.; Balieiro, J.C.D.C.; Ventura, R.V. Applications of Livestock Monitoring Devices and Machine Learning Algorithms in Animal Production and Reproduction: An Overview. Anim. Reprod. 2023, 20, e20230077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, A.; Mehmood, H.; Arshad, M.T.; Rasheed, A.; Noreen, S.; Gnedeka, K.T. Applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Managing Food Quality and Ensuring Global Food Security. CyTA—J. Food 2024, 22, 2393287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, A.; Aghababaei, F.; Pignitter, M.; Hadidi, M. Artificial Intelligence in Agro-Food Systems: From Farm to Fork. Foods 2025, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakeel, A.E. A Smart Automatic Control and Monitoring System for Environmental Control in Poultry Houses Integrated with Earlier Warning System. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, V.; Gaucel, S.; Fornaciari, C.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N. The Next Generation of Sustainable Food Packaging to Preserve Our Environment in a Circular Economy Context. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Escher, A.; Bertucci, S.; Castellano, M.; Lova, P. Intelligent Packaging for Real-Time Monitoring of Food-Quality: Current and Future Developments. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M.; Banach, J.K.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M. Shaping Poultry Meat Quality Attributes in the Context of Consumer Expectations and Preferences—A Case Study of Poland. Foods 2023, 12, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprianto, M.A.; Muhlisin; Kurniawati, A.; Hanim, C.; Ariyadi, B.; Anas, M.A. Effect Supplementation of Black Soldier Fly Larvae Oil (Hermetia illucens L.) Calcium Salt on Performance, Blood Biochemical Profile, Carcass Characteristic, Meat Quality, and Gene Expression in Fat Metabolism Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidhof, M.J.; Schneider, B.L.; Carney, V.L.; Korver, D.R.; Robinson, F.E. Growth, Efficiency, and Yield of Commercial Broilers from 1957, 1978, and 2005. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2970–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavárez, M.A.; de los Santos, F.S. Impact of Genetics and Breeding on Broiler Production Performance: A Look into the Past, Present, and Future of the Industry. Anim. Front. 2016, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, E.; Masoud, S.R. The Effect of Feeding Frequency and Amount on Performance, Behavior and Physiological Responses of Broilers. J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 2021, 6, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, R.A.; Schilling, M.W.; Silva, J.L.; Martin, J.M.; Corzo, A. The Effects of Dietary Amino Acid Density in Broiler Feed on Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2011, 20, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Rondón, E.O.; Velleman, S.G.; Wineland, M.J. The Role of Incubation Conditions in the Onset of Avian Myopathies. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 545045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajčić, A.; Baltić, M.Ž.; Lazić, I.B.; Starčević, M.; Baltić, B.; Vučićević, I.; Nešić, S. Intensive Genetic Selection and Meat Quality Concerns in the Modern Broiler Industry. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 854, p. 12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Stadnicka, K. The Science of Genetically Modified Poultry. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 9, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Shen, L.; Zhou, J.; Cao, Z.; Luan, P.; Li, Y.; Xiao, F.; Guo, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, H. Genome-Wide Association Studies for Growth Traits in Broilers. BMC Genom. Data 2022, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, H.; Habib, G.; Khan, I.M.; Rahman, S.U.; Khan, N.M.; Wang, H.; Khan, N.U.; Liu, Y. Genetic Resilience in Chickens against Bacterial, Viral and Protozoal Pathogens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1032983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeman, M.E. Management and Genetics Research to Improve the Quality of Animal Products: A Beef Perspective. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2002, 11, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes-Oliveira, J.M.; Kim, Y.H.B.; Conte-Júnior, C.A. What Are the Potential Strategies to Achieve Potentially More Healthful Meat Products? Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 6157–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mienaltowski, M.J. Broiler White Striping: A Review of Its Etiology, Effects on Production, and Mitigation Efforts. Poultry 2023, 2, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velleman, S.G. Broiler Breast Muscle Myopathies: Association with Satellite Cells. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Puolanne, E.; Schwartzkopf, M.; Arner, A. Altered Sarcomeric Structure and Function in Woody Breast Myopathy of Avian Pectoralis Major Muscle. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusairat, B.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Qudsieh, R.I. An Overview of Poultry Meat Quality and Myopathies. In Broiler Industry; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, K.; Cao, Q.; Shaukat, A.; Zhang, C.; Huang, S. Insights into the Evaluation, Influential Factors and Improvement Strategies for Poultry Meat Quality: A Review. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollan, N.D.; Price, E.M.; Morgan, S.A.; Huws, S.A.; Shingfield, K.J. Can We Improve the Nutritional Quality of Meat? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracci, M.; Soglia, F.; Madruga, M.S.; de Carvalho, L.M.; Ida, E.I.; Estévez, M. Wooden-Breast, White Striping, and Spaghetti Meat: Causes, Consequences and Consumer Perception of Emerging Broiler Meat Abnormalities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeteson, A.-M.; Avendaño, S.; Koerhuis, A.; Duggan, B.; Souza, E.; Mason, J.; Ralph, J.; Rohlf, P.; Burnside, T.; Kranis, A.; et al. Evolutions in Commercial Meat Poultry Breeding. Animals 2023, 13, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar, S.; Lee, E.S.; Leer, T.L.V.; Burlinguette, N.; Classen, H.L.; Crowe, T.G.; Shand, P.J. Effect of Microclimate Temperature during Transportation of Broiler Chickens on Quality of the Pectoralis Major Muscle. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, P. Characteristics of Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Broiler Chickens Reared under Conventional and Free-Range Systems. J. World’s Poult. Res. 2020, 10, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihan-Duval, E.L. Genetic Variability within and between Breeds of Poultry Technological Meat Quality. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2004, 60, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desire, S.; Johnsson, M.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Chen, C.-Y.; Holl, J.W.; Herring, W.O.; Gorjanc, G.; Mellanby, R.J.; Hickey, J.M.; Jungnickel, M.K. A Genome-Wide Association Study for Loin Depth and Muscle pH in Pigs from Intensely Selected Purebred Lines. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listrat, A.; Lebret, B.; Louveau, I.; Astruc, T.; Bonnet, M.; Lefaucheur, L.; Picard, B.; Bugeon, J. How Muscle Structure and Composition Influence Meat and Flesh Quality. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 3182746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patriani, P.; Hafid, H. The Effectiveness of Gelugur Acid (Garcinia Atroviridis) Marinade on the Physical Quality of Culled Chicken Meat. J. Ilmu Dan Teknol. Has. Ternak 2021, 16, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, S.; Lessire, M.; Corniaux, A.; Métayer-Coustard, S.; Mercerand, F.; Tesseraud, S.; Bouvarel, I.; Berri, C. Short-Term Nutritional Strategies before Slaughter Are Effective in Modulating the Final pH and Color of Broiler Breast Meat. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylä-Ajos, M.; Ruusunen, M.; Puolanne, E. Glycogen Debranching Enzyme and Some Other Factors Relating to Post-mortem pH Decrease in Poultry Muscles. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 87, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; LeMaster, M.N.; Clark, D.L.; Foster, M.K.; Miller, C.E.; England, E.M. Glycolysis and pH Decline Terminate Prematurely in Oxidative Muscles despite the Presence of Excess Glycogen. Meat Muscle Biol. 2019, 3, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriss, P.D.; Bevis, E.A.; Ekins, P.J. The Relationships between Glycogen Stores and Muscle Ultimate pH in Commercially Slaughtered Pigs. Br. Vet. J. 1989, 145, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G.C. (Ed.) Woodhead Publishing in Food Science and Technology. In Poultry Meat Processing and Quality; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-85573-727-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pena, R.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Tor, M.; Estany, J. Genetic Marker Discovery in Complex Traits: A Field Example on Fat Content and Composition in Pigs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Kaliniak-Dziura, A.; Prasow, M.; Domaradzki, P.; Litwińczuk, A. Meat Quality—Genetic Background and Methods of Its Analysis. Czech J. Food Sci. 2022, 40, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.-F.J.-F.; Gondret, F.; Baéza, É.; Médale, F.; Jurie, C.C.; Pethick, D.W. Intramuscular Fat Content in Meat-Producing Animals: Development, Genetic and Nutritional Control, and Identification of Putative Markers. Animal 2009, 4, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cui, H.; Xing, S.; Zhao, G.; Wen, J. Effect of Divergent Selection for Intramuscular Fat Content on Muscle Lipid Metabolism in Chickens. Animals 2019, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Beak, S.-H.; Jung, D.J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, I.H.; Piao, M.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Fassah, D.M.; Na, S.W.; Yoo, S.P.; et al. Genetic, Management, and Nutritional Factors Affecting Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Beef Cattle—A Review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, N.; Tan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhao, G.; Wen, J. A Selected Population Study Reveals the Biochemical Mechanism of Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Chicken Meat. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Hu, X.; Li, N. Application of Genomic Technologies to the Improvement of Meat Quality of Farm Animals. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneh, H.; Elatkin, N.; Gentzbittel, L. Genome-Wide Association Studies and Genetic Architecture of Carcass Traits in Angus Beef Cattle Using Imputed Whole-Genome Sequences Data. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2025, 57, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.K.; Kolluri, G. Selection Methods in Poultry Breeding: From Genetics to Genomics. In Application of Genetics and Genomics in Poultry Science; Liu, X., Ed.; InTech: Milton, QLD, Australia, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78923-630-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carpio, M.G.; Rossi, D.; Cimmino, R.; Zullo, G.; Gombia, Y.; Altieri, D.; Palo, R.D.; Biffani, S. Accounting for Genetic Differences Among Unknown Parents in Bubalus Bubalis: A Case Study From the Italian Mediterranean Buffalo. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 625335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Fregeau-reid, J. Breeding Line Selection Based on Multiple Traits. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, C.; Fuerst-Waltl, B.; Schwarzenbacher, H.; Steininger, F.; Fuerst, C. A Comparison of Methods to Calculate a Total Merit Index Using Stochastic Simulation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2015, 47, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Rojas, J.J.; Crossa, J. The Statistical Theory of Linear Selection Indices from Phenotypic to Genomic Selection. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell-Kubiak, E.; Wimmers, K.; Reyer, H.; Szwaczkowski, T. Genetic Aspects of Feed Efficiency and Reduction of Environmental Footprint in Broilers: A Review. J. Appl. Genet. 2017, 58, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.P.; Anthony, N.B.; Orlowski, S.; Rhoads, D.D. SNP-Based Breeding for Broiler Resistance to Ascites and Evaluation of Correlated Production Traits. Hereditas 2022, 159, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obe, T.; Boltz, T.P.; Kogut, M.H.; Ricke, S.C.; Brooks, L.A.; Macklin, K.S.; Peterson, A. Controlling Salmonella: Strategies for Feed, the Farm, and the Processing Plant. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 103086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Subramanian, M.; Kar, D. Breeding Techniques to Dispense Higher Genetic Gains. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1076094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, T.; Xiang, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, B.; Feng, Z.; Mu, Y.; Li, K. Enhancing Animal Disease Resistance, Production Efficiency, and Welfare through Precise Genome Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, M.; Akhavan, K. Molecular Marker Assisted Selection as Approach to Increase the Selection Efficiency of Drought Tolerant Genotypes. Int. J. Sci. World 2014, 2, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Khatun, R.; Mintoo, A.A. Application of Marker Assisted Selection for Livestock Improvement in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Vet. 2015, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Anthony, N.B.; Rowland, K.; Khatri, B.; Kong, B.-W. Genome Re-Sequencing to Identify Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Markers for Muscle Color Traits in Broiler Chickens. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 31, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, R.; Ganguly, S.; Praveen, P.K.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Mahajan, T. Marker Assisted Selection (MAS) in Animal Breeding: A Review. J. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2015, 6, e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.H.A.; Khan, R.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.; Ohran, H.; Mei, C.; Schreurs, N.M.; Zan, L. Advances of Molecular Markers and Their Application for Body Variables and Carcass Traits in Qinchuan Cattle. Genes 2019, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzenstock, F.; Ytournel, F.; Sharifi, A.; Cavero, D.; Täubert, H.; Preisinger, R.; Simianer, H. Efficiency of Genomic Selection in an Established Commercial Layer Breeding Program. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2013, 45, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.; Hayes, B.; Goddard, M. Accelerating Improvement of Livestock with Genomic Selection. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2013, 1, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, D.; Maurya, A.K.; Abdi, G.; Majeed, M.; Agarwal, R.; Mukherjee, R.; Ganguly, S.; Aziz, R.; Bhatia, M.; Majgaonkar, A.; et al. Integrated Genomic Selection for Accelerating Breeding Programs of Climate-Smart Cereals. Genes 2023, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolc, A.; Zhao, H.; Arango, J.; Settar, P.; Fulton, J.E.; O’Sullivan, N.; Preisinger, R.; Stricker, C.; Habier, D.; Fernando, R.L.; et al. Response and Inbreeding from a Genomic Selection Experiment in Layer Chickens. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2015, 47, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, P.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Lu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Meng, Z. Genomic Selection on Shelling Percentage and Other Traits for Maize. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.E.; Wilson, P.B. Progress and Opportunities through Use of Genomics in Animal Production. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 1228–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, K.; Reents, R. Genomic Selection: Status in Different Species and Challenges for Breeding. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2013, 48, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, A.M.; Boschiero, C.; Balieiro, J.C.C.; Ledur, M.C.; Ferraz, J.B.S.; Michelan Filho, T.; Moura, A.S.A.M.T.; Coutinho, L.L. Identification and Association of Polymorphisms in CAPN1 and CAPN3 Candidate Genes Related to Performance and Meat Quality Traits in Chickens. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tu, Y.; Ji, G.; Ju, X.; Shu, J.; Liu, Y. Genome-Wide Association Study of Myofiber Type Composition Traits in a Yellow-Feather Broiler Population. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, S.; Jin, P.; Luan, P.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Leng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Differential Expression of Six Chicken Genes Associated with Fatness Traits in a Divergently Selected Broiler Population. Mol. Cell. Probes 2015, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, A.A.; Lindsay, K.L.; Alberdi, G.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Gibney, E.R. Nutrition during Pregnancy Impacts Offspring’s Epigenetic Status—Evidence from Human and Animal Studies. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2015, 8s1, NMI.S29527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeagha-Awemu, E.M.; Zhao, X. Epigenetic Marks: Regulators of Livestock Phenotypes and Conceivable Sources of Missing Variation in Livestock Improvement Programs. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, F.-B.; Li, F.; Jiang, K.-R.; Li, D.-H.; Han, R.-L.; Li, Z.-J.; Jiang, R.-R.; Liu, X.-J.; Kang, X.-T.; et al. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiles Reveal Novel Candidate Genes Associated with Meat Quality at Different Age Stages in Hens. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Lv, Z.; Guo, Y. Research Advances in Intramuscular Fat Deposition and Chicken Meat Quality: Genetics and Nutrition. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, N.; Deng, X.; Lian, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, C. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Analysis on Chicken Extracelluar Fatty Acid Binding Protein Gene and Its Associations with Fattiness Trait. Sci. China Ser. C Life Sci. 2001, 44, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royan, M. The Immune-Genes Regulation Mediated Mechanisms of Probiotics to Control Salmonella Infection in Chicken. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengstie, M.A.; Wondimu, B.Z. Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas-9-Mediated Genome Editing. BTT 2021, 15, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansori, A.N.; Antonius, Y.; Susilo, R.J.; Hayaza, S.; Kharisma, V.D.; Parikesit, A.A.; Zainul, R.; Jakhmola, V.; Saklani, T.; Rebezov, M.; et al. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Technology in Various Fields: A Review. Narra J. 2023, 3, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi-Zheng, G.; Zhao, S. Physiology, Affecting Factors and Strategies for Control of Pig Meat Intramuscular Fat. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2009, 1, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Gomez, N.A.; Gao, Y.; Son, J.S.; Chae, S.A.; Zhu, M.-J.; Du, M. Stage-Specific Nutritional Management and Developmental Programming to Optimize Meat Production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebezov, M.; Khayrullin, M.; Assenova, B.; Farida, S.; Baydan, D.; Garipova, L.; Savkina, R.; Rodionova, S. Improving Meat Quality and Safety: Innovative Strategies. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2024, 18, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, C.J.; Jackson, A.R.; Caldas-Cueva, J.P.; Mauromoustakos, A.; Kidd, M.T.; Rochell, S.J.; Owens, C.M. Meat Quality Attributes of Male and Female Broilers from 4 Commercial Strains Processed for 2 Market Programs. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bihan-Duval, E.; Berri, C. Genetics and Genomics for Improving Poultry Meat Quality. In Poultry Quality Evaluation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 199–220. ISBN 978-0-08-100763-1. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bihan-Duval, E.; Berri, C.; Pitel, F.; Nadaf, J.; Sibut, V.; Gigaud, V.; Duclos, M. Approches Combinées de Génomique Positionnelle et Expressionnelle Pour l’étude Des Gènes Contrôlant La Qualité de La Viande Chez Les Volailles. INRA Prod. Anim. 2008, 21, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, B. Broylerlerde Beslenme Stratejilerinin Karkas Kalitesi Üzerine Etkileri. Turk. JAF Sci. Tech. 2025, 13, 2858–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Elnesr, S.S.; Farag, M.R.; El-Naggar, K.; Madkour, M. Nutrigenomics and Nutrigenetics in Poultry Nutrition: An Updated Review. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2022, 78, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, B.M.; Murdoch, G.K.; Greenwood, S.; McKay, S. Nutritional Influence on Epigenetic Marks and Effect on Livestock Production. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Alagawany, M.; Jha, R. Editorial: Interplay of Nutrition and Genomics: Potential for Improving Performance and Health of Poultry. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1030995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, B.; Mahlet, D.; Brhane, H. Livestock Nutrigenomics Applications and Prospects. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métayer-Coustard, S.; Tesseraud, S.; Praud, C.; Royer, D.; Bordeau, T.; Coudert, E.; Cailleau-Audouin, E.; Godet, E.; Delaveau, J.; Le Bihan-Duval, E.; et al. Early Growth and Protein-Energy Metabolism in Chicken Lines Divergently Selected on Ultimate pH. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 643580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ahn, D.U. The Incidence of Muscle Abnormalities in Broiler Breast Meat—A Review. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018, 38, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnahhas, N.; Pouliot, E.; Saucier, L. The Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Pathway Plays a Critical Role in the Development of Breast Muscle Myopathies in Broiler Chickens: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1260987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Approach | Key Factors/Tools | Primary Effects on Meat Quality | Mechanisms/Pathways | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management | ||||

| Rearing environment | Optimal stocking density, temperature–humidity control, dry litter, ventilation | Improved texture and colour; reduced PSE/DFD; lower oxidative stress | Lower stress hormones; stabilized glycolysis; controlled heat load | [8,9,10,11,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] |

| Antibiotics and alternatives | Probiotics, prebiotics, organic acids, phytogenic additives | Better gut integrity, nutrient absorption, reduced contamination | Microbiota stabilization; improved immunity and digestion | [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] |

| Husbandry & welfare | Handling, lighting, enrichment | Fewer defects, better WHC, improved colour | Reduced stress-induced rapid pH decline | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,73,74,75] |

| Thermal stress management | Evaporative cooling, ventilation, insulation | Prevents PSE-like meat; uniform muscle development | Avoids metabolic imbalance; maintains feed intake | [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,60,61,62,63,72] |

| Litter & air quality control | Litter turning, moisture management, ammonia control | Fewer lesions; better hygiene and skin integrity | Reduced inflammation; less bacterial overgrowth | [14,15,16,17,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] |

| Pre-slaughter management | Feed withdrawal strategy; gentle handling | Better colour; improved WHC; fewer bruises | Reduced cortisol; smoother rigor mortis transition | [88,89,90] |

| Stunning and slaughter | Electrical/gas stunning; proper bleed-out | Enhanced tenderness; reduced PSE/DFD | Controlled rigor onset; regulated glycolysis | [91,92,93,94,95,96] |

| Chilling & food safety | Rapid chilling; sanitation; HACCP/SSOP | Extended shelf life; better colour retention | Reduced bacterial growth; preserved protein integrity | [71,92,95] |

| Genetic | ||||

| Conventional breeding | Phenotypic selection; BLUP; multi-trait indices | Improved tenderness, pH stability, carcass yield | Selection on muscle structure, collagen, fat deposition | [146,149,150] |

| Marker-assisted selection | SNP markers; QTL mapping | Improved WHC, IMF, tenderness | Genes for fibre type, lipid metabolism (CAPN1/3, FASN) | [58,59,145] |

| Genomic selection | Dense SNP panels; GEBVs | Early selection for pH, tenderness, myopathy resistance | Captures many small-effect loci | [146,150] |

| Functional genomics | RNA-seq; epigenetics; proteomics | Insight into WB/WS; improved IMF prediction | Pathways: oxidative stress, calcium handling | [58,59,140,141,142] |

| Gene editing | CRISPR/Cas9; targeted edits | Potential improvements in muscle growth and quality | Precise gene modification (e.g., MSTN) | [143,144,145,146] |

| Integrated genetic × environment | Precision housing + genomic tools | Resilience to heat stress; reduced WB/WS | Gene–environment interaction | [143,146] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Naeem, M.; Fatima, A.; Raut, R.; Kumar, R.; Tushar, Z.; Rahman, F.; Bourassa, D. Management and Genetics Approaches for Enhancing Meat Quality in Poultry Production Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Poultry 2026, 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010004

Naeem M, Fatima A, Raut R, Kumar R, Tushar Z, Rahman F, Bourassa D. Management and Genetics Approaches for Enhancing Meat Quality in Poultry Production Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Poultry. 2026; 5(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaeem, Muhammad, Arjmand Fatima, Rabin Raut, Rishav Kumar, Zahidul Tushar, Farazi Rahman, and Dianna Bourassa. 2026. "Management and Genetics Approaches for Enhancing Meat Quality in Poultry Production Systems: A Comprehensive Review" Poultry 5, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010004

APA StyleNaeem, M., Fatima, A., Raut, R., Kumar, R., Tushar, Z., Rahman, F., & Bourassa, D. (2026). Management and Genetics Approaches for Enhancing Meat Quality in Poultry Production Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Poultry, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010004