1. Introduction

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) have become a focal point in the financial landscape as a novel monetary instrument. This paper examines their effects on mobile money and outstanding loans from commercial banks, analyzed through the lens of financial inclusion (FI). Although the timeframe for analysis remains limited—given that the first CBDC was launched in the Bahamas in 2020—this study aims to provide an empirical assessment of the effects of CBDCs. Research in this area is constrained by the scarcity of data regarding CBDC implementation. Therefore, this paper seeks to bridge this gap in the literature, offering a foundation for future studies as more evidence becomes available to clarify the evolving role of CBDCs in the global economy.

One of the primary concerns surrounding CBDCs is the “deposit substitution risk” [

1], which highlights the potential for banking disintermediation if individuals shift their funds from commercial banks to CBDCs, thereby reducing banks’ lending capacity. In the worst-case scenario, this could lead to higher credit costs and even “trigger financial instability” [

2]. Accordingly, this paper assesses whether the SandDollar has influenced outstanding loans in the Bahamas. However, some argue that integrating the unbanked population into the financial system through CBDCs could enhance, rather than undermine, existing financial structures by increasing deposit levels and, consequently, lending capacity [

3].

Given the broad implications of CBDCs across the financial sector, this research narrows its focus to their effects on commercial bank loans and mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP. The analysis of the first variable is conducted using data from the Bahamas’ SandDollar within the Caribbean context, while mobile money transactions are examined through the Nigerian eNaira with comparisons to Sub-Saharan African (SSA) counterparts. This methodological decision is based on data availability and alignment with the research objectives.

To ensure clarity, the key variables under study are defined as follows:

“Outstanding loans with commercial banks (percentage of the GDP)” refers to “the total amount (in millions of national currency) of all types of outstanding loans held by resident nonfinancial corporations (both public and private) and individuals from the household sector with commercial banks, expressed as a percentage of the GDP” [

4].

“The value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP” represents “the total amount (in millions of national currency) of all mobile money transactions conducted within the reference period, expressed as a percentage of the GDP” [

4].

Beyond their formal definitions, these variables are intrinsically linked to FI, as they reflect access to capital through loans and the adoption of Fintech instruments such as mobile money, both of which play critical roles in digital FI [

5].

Regarding the global expansion of CBDCs, data from central banks indicate that 134 CBDC projects exist worldwide, yet only three, equivalent to 2.2% of the total, have been fully launched. These include the Bahamas’ SandDollar (in effect since October 2020), Jamaica’s JAM-DEX (introduced in 2022), and Nigeria’s eNaira (implemented in October 2021) [

6].

Based on this information, the Bahamas was selected over Jamaica due to the better availability of post-intervention data for 2021 and 2022, which facilitates a more robust observational analysis of SandDollar’s potential effects compared to other Caribbean control units. Nigeria was chosen as the only Sub-Saharan African country with an active CBDC, a crucial selection given Africa’s status as a global leader in mobile money adoption [

7]. The availability of official public data in this region further supports the feasibility of measuring mobile money indicators. To conduct this empirical analysis, the selected variables are categorized into four groups, FI, economic indicators, demographics, and digital infrastructure, as detailed in the empirical analysis section.

FI is defined as “the availability and equality of opportunities to access financial services, enabling individuals and businesses to obtain appropriate, affordable, and timely financial products and services” [

8]. Digital FI, in turn, refers to the use of technology to enhance access to financial services, particularly among underserved populations [

9]. Fintech solutions, including CBDCs, are thus viewed as disruptive innovations with the potential to improve FI.

From a global perspective, the role of FI in CBDC development varies by economic context. In emerging and developing economies, FI is a primary motivation, whereas in advanced economies, greater emphasis is placed on monetary sovereignty and payment efficiency [

10]. As a result, CBDCs are designed with diverse objectives beyond FI, including monetary policy, financial stability, and taxation, which influence their technical specifications.

Access to financial services and monetary instruments that facilitate commercial transactions is essential for economic development. Both the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank (WB) acknowledge that financial exclusion is most pronounced in remote areas, where Fintech solutions, including CBDCs, can serve as viable alternatives due to the challenges of cash accessibility in geographically dispersed regions with limited economic activity [

11]. However, the discourse on FI extends beyond mere access to bank accounts, as true FI encompasses essential services such as credit, savings, and investment [

12].

The broader goal of FI is to integrate excluded populations into the formal financial system, providing them with a comprehensive range of financial services that improve their quality of life and economic prospects. Increased FI fosters entrepreneurship, enhances domestic production, and contributes to GDP growth [

13]. Moreover, universal financial access is linked to the promotion of democratic values by ensuring a more equitable distribution of wealth [

5]. As part of this process, Fintech solutions, such as CBDCs and mobile money, serve as strategic instruments for achieving FI objectives. This perspective aligns with statements from Chinese officials, who have emphasized that efforts to promote FI drive their adoption of Fintech innovations like CBDCs, particularly in a country where 10% of the population lacks access to basic financial services [

14]. In these terms, we approach this analysis from the viewpoint of FI.

This study contributes to the academic discourse by addressing the lack of empirical research on the economic effects of CBDCs, particularly their impact on FI through commercial bank loans and mobile money transactions. To date, much of the literature has focused on theoretical frameworks, technical specifications, and implementation strategies for CBDCs. By providing new empirical insights, this paper enhances the existing body of knowledge and informs future research and policy discussions.

To summarize, this paper aims to assess the post-treatment effects of CBDCs on mobile money and outstanding loans from commercial banks using the Synthetic Control Method for the Bahamas and Nigeria. The research questions guiding this study are as follows: (1) What has been the impact of the SandDollar launch on outstanding loans from commercial banks as a percentage of the GDP in the Bahamas? And (2) What has been the impact of the eNaira launch on the value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP in Nigeria? Consecutively, the hypotheses are that (I) the implementation of the SandDollar could decrease the outstanding loans from commercial banks, considering that people could prefer to keep their formal savings in CBDCs instead of commercial banks, which would decrease their liquidity, and (II) the eNaira launch in Nigeria should trigger an increase in the value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP, considering its nature and direct relationship with this sort of digital means. Finally, the remainder of the article paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology;

Section 3 provides the literature review;

Section 4 describes the empirical analysis;

Section 5 outlines the findings;

Section 6 presents the conclusions; and Reference part concludes with the references.

3. Literature Review

The structure of this literature review was designed first to establish the social relevance of the research topic. To that end, reference was made to how Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) align with this research. Then, the review introduces the general concept of the topic—Fintech—emphasizing its connection to financial inclusion (FI).

Subsequently, the discussion narrows to Fintech developments related to blockchain technology. This leads to the core focus of this research: Fintech innovations such as mobile money (MM) and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). For these two instruments, we provide an overview of global trends, including relevant statistics, levels of implementation and penetration, as well as regulatory frameworks. Finally, the review concludes with an examination of the technical specifications and challenges associated with these financial instruments.

Recent Fintech developments are of paramount importance for advancing several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In light of the seventeen SDGs established by the United Nations, and beyond the broad range of connections between financial inclusion (FI) and these goals, we identified four specific targets across three distinct SDGs that directly relate to Fintech and financial innovation. These are presented in

Table 1.

Hence, analyzing Fintech tools such as CBDCs and MM through the lens of the SDGs is pertinent. These innovations offer viable alternatives to traditional, often exclusionary, financial systems, where an author argues, “money, as we know it, cannot be the appropriate tool to be utilized in a democratization process” [

5]. Henceforth, Fintech innovations such as MM and CBDCs emerge as promising mechanisms for promoting financial inclusion as pursued by the SDGs.

Moreover, Fintech tools facilitate project funding through mechanisms such as crowdfunding, addressing a range of social needs that can contribute to improved living standards. By enhancing financial interactions among donors, investors, public entities, and aid recipients, these technologies reduce transaction costs [

19], thereby increasing the efficiency and volume of fund allocation.

MM has also favored financial inclusion (FI). In Sub-Saharan Africa, MM has replaced traditional banking: MM’s expansion has been inversely correlated with the growth of commercial bank accounts [

20]. Fintech innovations have demonstrably improved FI, as illustrated by the case of M-Pesa in Kenya. In 2014, 55% of Kenyan adults held accounts with financial institutions (an increase from 42% in 2011), while 58% had MM accounts. By 2017, traditional banking had stagnated at 56%, whereas MM adoption had risen to 73% [

21]. This divergence, often referred to as the “inclusion gap”, underscores the broader and more rapid outreach of MM compared to conventional financial institutions.

Between 2011 and 2021, bank account ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa rose by 50%, reaching 76%. In contrast, developing economies as a whole experienced only an 8% increase, from 61% to 71%. However, 33% of adults in Sub-Saharan Africa use now MM services [

20], a proportion nearly half the number of traditional bank account holders.

Additionally, the advancement of blockchain technology has driven the emergence of cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, and, more recently, Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). These digital currencies are often regarded as more efficient and inclusive financial instruments, particularly due to their regulation and oversight by central banks [

2]. CBDC account models are typically categorized as either direct or indirect. In direct models, users hold accounts with the central bank; in indirect models, financial intermediaries manage user accounts. Projects such as the e-krona (in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden), the Sand Dollar (Bahamas), and Rafkróna (Iceland) exemplify direct retail CBDCs. However, such models may place non-traditional responsibilities, such as customer due diligence and payment services, on central banks [

22].

Although CBDCs are designed by monetary authorities and aim to strengthen the transmission of monetary policy [

8], concerns persist regarding their potential to destabilize the financial system. Direct models that bypass traditional banks may reduce deposit levels, causing disintermediation and limiting banks’ ability to lend, thus posing liquidity and credit risks [

3]. Nevertheless, some argue that in competitive financial markets, increased deposits from previously unbanked individuals could lower borrowing costs, improve monetary policy transmission, and reduce income inequality [

13].

In Nigeria, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has cited FI, reducing informality and facilitating remittances as the primary motivations behind the development of the eNaira as a CBDC [

7]. Initially, eNaira wallets were only available to individuals with bank accounts. However, in August 2022, access was expanded to anyone with a smartphone, recognizing that 36% of Nigerian adults (38 million people) remain unbanked. Despite this, Nigeria has one of the highest mobile penetration rates in Africa [

7], presenting an opportunity to enhance FI.

Furthermore, Nigeria’s informal economy accounts for over half of the GDP and 80% of employment [

7]. The account-based nature of the eNaira aims to enhance financial accountability in this large informal sector while also improving tax collection. Moreover, remittances, often used by expatriates to support families, play a critical role in financial stability. The efficiency of Fintech solutions, such as MM and eNaira, helps reduce cross-border remittance fees, ensuring accessibility even for those without financial services [

23]. Moreover, as part of anti-poverty initiatives, Nigeria has implemented cash transfer programs that could be more effectively distributed via eNaira, potentially replacing MM as the primary tool for FI [

7].

In the United States, CBDC is conceived as a government-backed instrument intended to complement, not replace, physical cash [

24]. By reducing reliance on intermediaries, a digital dollar would replicate some characteristics of cash transactions [

25]. However, current regulations prohibit individuals from holding accounts directly with the Federal Reserve, as this would broaden its institutional role [

26]. Accordingly, U.S. authorities advocate for an intermediated two-tier model to maintain financial stability and leverage existing institutions.

In the European Union, the European Central Bank (ECB) is exploring distribution models for a potential digital euro. The Eurosystem seeks to ensure broad access through both public and private channels, with a focus on financial inclusion for vulnerable populations [

27]. To promote adoption, the ECB highlights the importance of effective distribution incentives [

27]. The shift from cash to digital currency is widely viewed as a natural monetary evolution [

28].

The successful implementation of the digital euro hinges on its ability to safeguard financial stability, particularly by preventing large-scale withdrawals from commercial banks. As a means of payment rather than a store of value, the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) must be clearly understood by the public to minimize liquidity risks [

28].

Beyond CBDCs, Fintech platforms have extended financial services to underbanked or “subprime” borrowers [

29]. Whereas these platforms have expanded credit access, they have also enabled the circumvention of usury laws by facilitating lending in jurisdictions with higher or no interest rate caps. This raises concerns about regulatory arbitrage, though some view it as a positive development in financial inclusion.

However, Fintech has favored the shadow economy [

30]. The shadow economy includes not only illegal activities—such as drug trafficking, arms smuggling, human trafficking, and tax evasion—but also informal labor and unregulated commercial transactions. Between 1991 and 2017, the global shadow economy was estimated to account for 30.9% of the global GDP. In the United States, this figure was 7.6%, equivalent to approximately USD 1.4 trillion [

30]. Within the U.S., Mississippi recorded the largest shadow economy between 1997 and 2008, averaging 9.54%, while Delaware had the smallest, at 7.28% [

31]. Additionally, informal employment—largely driven by cash transactions—represents 61.2% of the global workforce, or around two billion workers. In North America, this figure is 18.1% [

32].

Several structural challenges must be addressed to ensure the effectiveness of MM and CBDCs. These include identification barriers, infrastructure deficits, and user awareness. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the critical role of identification in financial inclusion (FI), particularly in developing countries. Globally, 4.4 billion people face identification challenges: 3.4 billion lack a valid ID, and 1 billion have no ID at all [

12]. Irregular migrants are especially affected. While reducing ID requirements could broaden financial access, it also raises concerns about the potential for illicit financial activities.

Limited electricity access, affecting approximately 700 million people, and inadequate internet connectivity, which impacts around 3 billion individuals globally, hinders access to MM and CBDC [

13]. Despite this, 65% of the world’s 1.7 billion unbanked population (1.1 billion people) own smartphones, indicating a significant potential for expanding digital financial services. Bridging this digital divide through public–private initiatives, such as programs for distributing refurbished phones, could enhance financial access while also benefiting data-driven commercial enterprises [

33].

Technological infrastructure and digital literacy are viewed as more pressing concerns than identification barriers, particularly in regions where CBDC adoption may reduce reliance on cash [

34]. To mitigate this, governments should invest in digital education, strengthen cybersecurity frameworks, and build the institutional capacity of regulatory bodies to supervise digital service providers, combat cyber threats, and protect consumer rights [

34].

Moreover, access to electricity, reliable internet, and formal identification must be stable and affordable to prevent systemic barriers to CBDC adoption [

35]. According to the World Bank, financial inclusion (FI) entails access to affordable and effective financial products and services, including payments, savings, credit, and insurance [

36]. Yet, exclusion remains widespread. The largest unbanked adult populations are found in China (130 million), India (230 million), Pakistan (115 million), and Indonesia (100 million), with countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, and Nigeria collectively accounting for more than half of the global unbanked population [

20].

Marginalized groups, such as women, youth, rural residents, low-income individuals, minorities, immigrants, and refugees, are disproportionately excluded from formal financial systems [

13]. Notably, while 77% of working adults globally have bank accounts, this figure drops to 65% among those outside the labor force [

20]. Rural populations are particularly affected; in Nigeria, for example, only 20% of rural adults have bank accounts [

20]. Furthermore, strategies for CBDC expansion in remote areas must differ from traditional banking approaches. Historically, commercial banks have prioritized credit availability for wealthy households in rural areas rather than broad-based FI [

37]. This phenomenon, which is particularly evident in India, underscores the role of information asymmetries and transaction costs in banking exclusion. In contrast, MM adoption in Kenya has demonstrated that lower transaction fees can reduce poverty rates by approximately 2% [

37].

Some scholars argue that CBDCs could serve as a gateway to formal financial inclusion by incentivizing unbanked populations to join the financial system. Additionally, the transactional data generated through CBDC use may increase deposit volumes, potentially reducing loan interest rates and enhancing overall financial intermediation [

3].

According to the IMF, a CBDC issuance could increase total lending by 2.2%, raise bank account ownership from 75% to 92.4%, and be adopted by 46.8% of the population as a payment method. However, the IMF emphasizes that a two-tiered model, where commercial banks serve as intermediaries, is the least disruptive and most effective [

3].

The literature presents ongoing debates regarding whether central banks should partner with private banks to mitigate financial system disruptions. Further research is needed to determine whether such partnerships enhance CBDC implementation while allowing for the coexistence of bank-issued credit and CBDC services. This study aims to contribute to the discourse by analyzing two leading CBDC case studies. In any scenario, CBDC adoption is likely to reshape the traditional money supply system and expand the role of central banks in daily economic operations [

23].

Finally, despite its descriptive nature, this literature seeks to provide a broad outlook for CBDC and MM, starting from general aspects such as the SDGs and Fintech, until we reach the point where we will depart from this research. It is compulsory to consider all the contexts of these two instruments in order to understand, firstly, the lack of empirical analysis due to the early stage of CBDC, and, secondly, why it is important to contribute to constructing more empirical evidence in this regard.

4. Empirical Analysis

The geographical delimitation of this research is determined by the two regions with active CBDCs; the first one is SSA, where the Nigerian eNaira operates. Also, it is crucial for the mobile money analysis, considering that this region stands as one of the most proactive worldwide. The second region is the Caribbean, which has two countries with CBDCs in force: the Bahamas and Jamaica. The Bahamas was selected due to its SandDollar, launched in 2020, which is a CBDC that is significantly older than the Jamaican CBDC implemented in 2022. Hence, there is more information available to analyze the Bahamas case. Additionally, there is an insufficient level of data on disposal to consider the selected variables in Jamaica.

We have chosen the control units in both cases by considering the following parameters: location (all countries belonging to the same region of the world), culture, access to the sea, industrialization, tourism, and macroeconomic alikeness. But most importantly, we have chosen countries that have also published official data for the variables taken into account for conducting the SCM analysis. For instance, in the case of SSA, not all the countries had MM data released; therefore, they were not suitable candidates for the comparison. A similar situation occurred with the Caribbean, where the lack of data for the dependent variable and the special predictors was limited to certain countries. Hence, adding these requirements, we obtained a pool of suitable candidates to form the control group.

We progressively present the organization of the dataset and its explanation for each case, followed by the SCM analysis. This includes graphical representations of the weighted averages and comparisons between the real and synthetic versions, summarizing the key characteristics of the analysis and the outcomes of the hypotheses for both research questions. Hence, for the first case study, the following are the main characteristics:

CARIBBEAN

- -

Pre-intervention period—2012–2020 T = 0;

- -

CBDC implementation—October 2020.

- -

Post-intervention period—2021–2022 T = 1;

- -

Treatment group—the Bahamas (SandDollar);

- -

Control group—Barbados, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Honduras, Mauritius, Panama, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago;

- -

Dependent variable—outstanding loans from commercial banks %;

- -

Special predictors—

- ○

Credit cards per 1000 adults;

- ○

Commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults;

- ○

Outstanding deposits with commercial banks (% of the GDP).

Concerning the variables contemplated for the analysis, we classified them into five indicator themes, as exhibited next in

Table 2.

In reference to the variable selection, we have first included standard measures of financial inclusion, such as the number of credit cards or the volume of loans. As control variables, and in part following the Quantity Theory of Money, we have opted for variables such as GDP, inflation, or population growth, as well measures of financial stability. This variable selection ensures a robust and credible counterfactual for estimating the CBDC’s impact on outstanding loans. Their inclusion supports the SCM’s goal of isolating the treatment effect by closely replicating the pre-intervention trajectory of the Bahamas with a synthetic unit composed of comparable economies.

Additionally, for the given description for the SCM Caribbean data, next it is displayed the mathematical formula of the analysis to process the results for the CBDC intervention effects on the topic:

is the dependent variable (outstanding loans from commercial banks %) for country i at time t;

i = 1 the treatment unit (the Bahamas);

i = 2, 3, …, J + 1 the control units (Barbados, Costa Rica, etc.);

= pre-intervention period of 2012–2020;

= post-intervention period of 2021–2022.

, the weight vector assigned to each control unit, where

The synthetic control is constructed by minimizing the distance between the treatment unit and the weighted control group in the pre-intervention period:

where

The weights W are chosen to ensure that the synthetic Bahamas best replicates the pre-2021 trajectory of outstanding loans from commercial banks %.

The counterfactual outcome for the Bahamas in the post-intervention period is given by

Here,

is the actual outcome for control units in the post-treatment period. Finally, the estimated treatment effect of the CBDC implementation is

A negative or positive

indicates a decrease or increase in outstanding loans relative to the synthetic Bahamas.

Generally, the Caribbean dataset presents 1320 observations for the eleven control countries plus one treatment country, with a total of nine control variables and one dependent variable, concerning a period from 2012 to 2022. Regarding the SCM, the first result to be displayed is the weighted average of each country to the synthetic Bahamas, as illustrated in

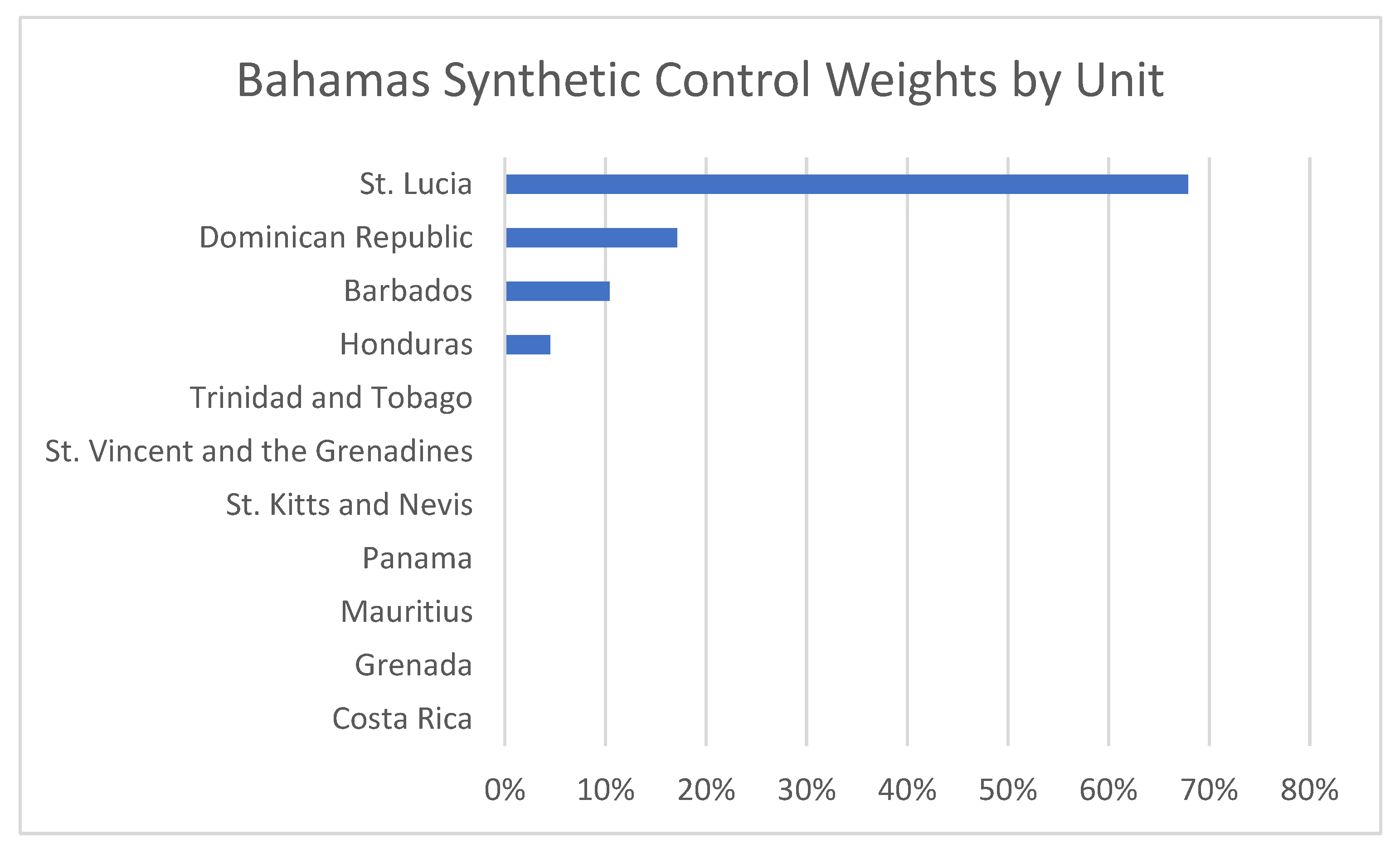

Figure 1. Out of the eleven control units, the software only considered four countries and designated the following percentages for the synthetic Bahamas: Barbados 10.4%, Dominican Republic 17.1%, Honduras 4.5%, and St. Lucia 67.9%.

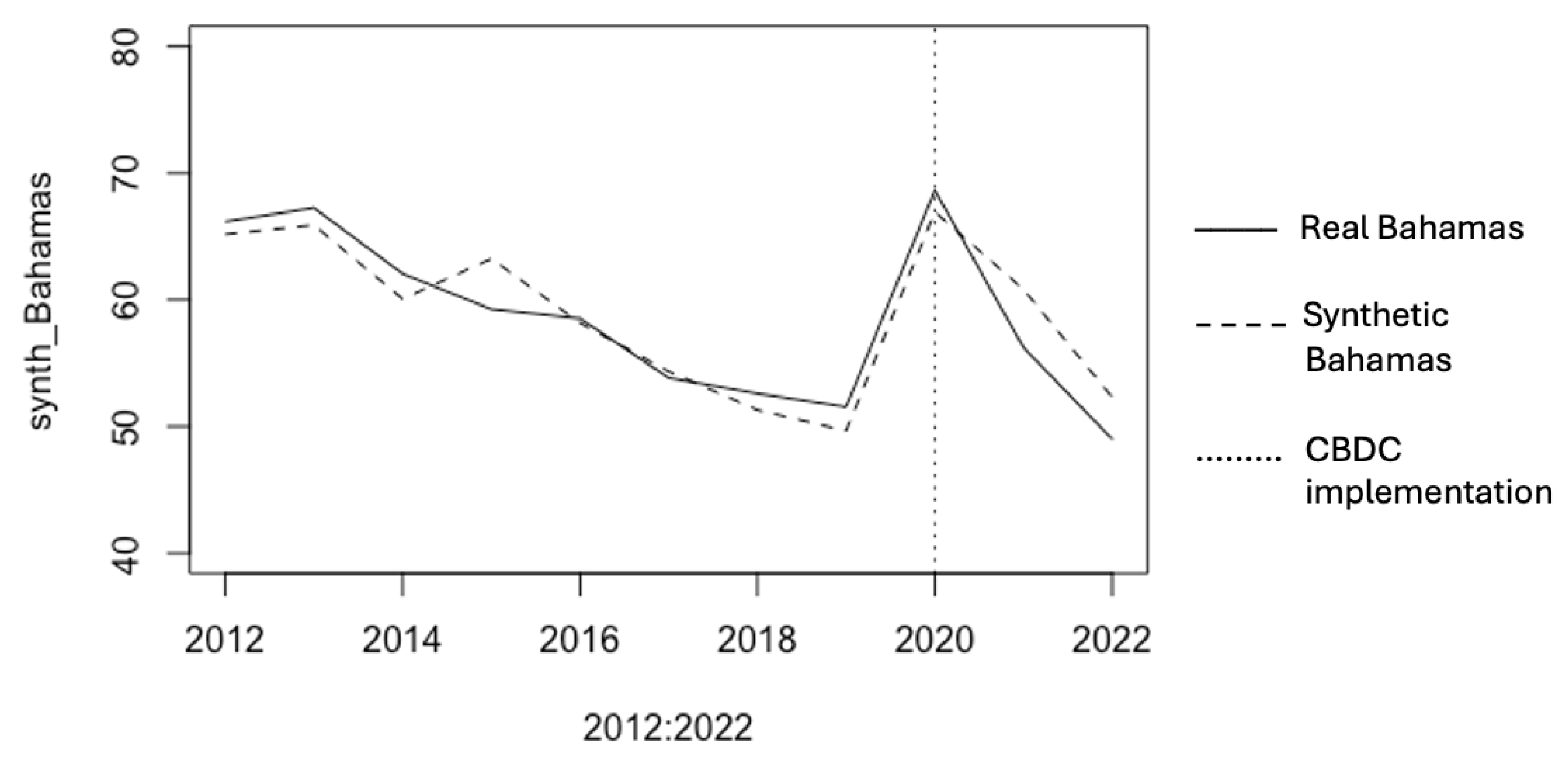

Once the weighted averages were determined, we show in

Figure 2 the comparison between the real Bahamas (represented by the solid line) and its synthetic result (marked with the dashed line) for the dependent variable (

Y-axis) “outstanding loans from commercial banks %”; there is also a vertical dashed line in 2020 to identify the intervention point in the graphic on the X axis corresponding to the period between 2012 and 2022. From

Figure 1, we can argue that the real and the synthetic Bahamas behaved significantly close to each other, with a substantial deviation after the treatment point.

Concerning the first research question, “What has been the impact of the SandDollar launch on outstanding loans from commercial banks as a percentage of the GDP in the Bahamas?” we could claim that real Bahamas’ performance falls below the synthetic control, implying that the CBDC may have contributed to a decline in outstanding loans. Hence, we confirm the first hypothesis: “The implementation of the SandDollar could decrease the outstanding loans from commercial banks considering that people could prefer to keep their formal savings in CBDCs instead of commercial banks, which would decrease their liquidity.”

After the Caribbean analysis with the Bahamas case, we proceed to conduct the African analysis and the eNaira example under the same framework as the previous study. Consequently, we next initiate an explanation of the variables and structure.

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

- -

Pre-intervention period—2015–2021 T = 0;

- -

CBDC implementation—October 2021;

- -

Post-intervention period—2022 T = 1;

- -

Treatment group—Nigeria (e-Naira);

- -

Control group—Angola, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda;

- -

Dependent variable—value of mobile money transactions % of the GDP;

- -

Special predictors—

- ○

MM agent outlets per 100,000 adults;

- ○

MM accounts per 1000 adults;

- ○

MM transactions per 1000 adults.

These MM-specific indicators reflect infrastructure availability, user adoption, and transaction behavior, all of which influence the outcome variable. Economic indicators account for macroeconomic conditions that shape demand for financial services. Financial inclusion variables distinguish between formal financial access and digital alternatives. Meanwhile, digital infrastructure measures are essential enablers of MM and CBDC functionality. Finally, population growth serves as a demographic control to account for scale effects. Together, these predictors as listed in

Table 3 ensure that the SCM is constructed from units that closely resemble Nigeria’s pre-treatment trajectory in both the structural and behavioral dimensions, thus enhancing the credibility of the counterfactual estimation.

Similarly, along with the SCM SSA data illustrated, we proceed with the same formula displayed in the previous Caribbean case, nonetheless, with the following differentiation in the variables:

is the dependent variable (value of mobile money transactions % of the GDP) for country i at time t;

= pre-intervention period of 2015–2021;

= post-intervention period of 2022;

i = 1 the treatment unit (Nigeria);

i = 2, 3, …, J + 1 the control units (Angola, Cote d’Ivoire, etc.).

Moreover, SSA possesses 1144 observations defining one treatment and twelve control variables from one intervention and ten control units (countries in the region), containing a period from 2015 to 2022. Moreover, advancing to the SCM, in

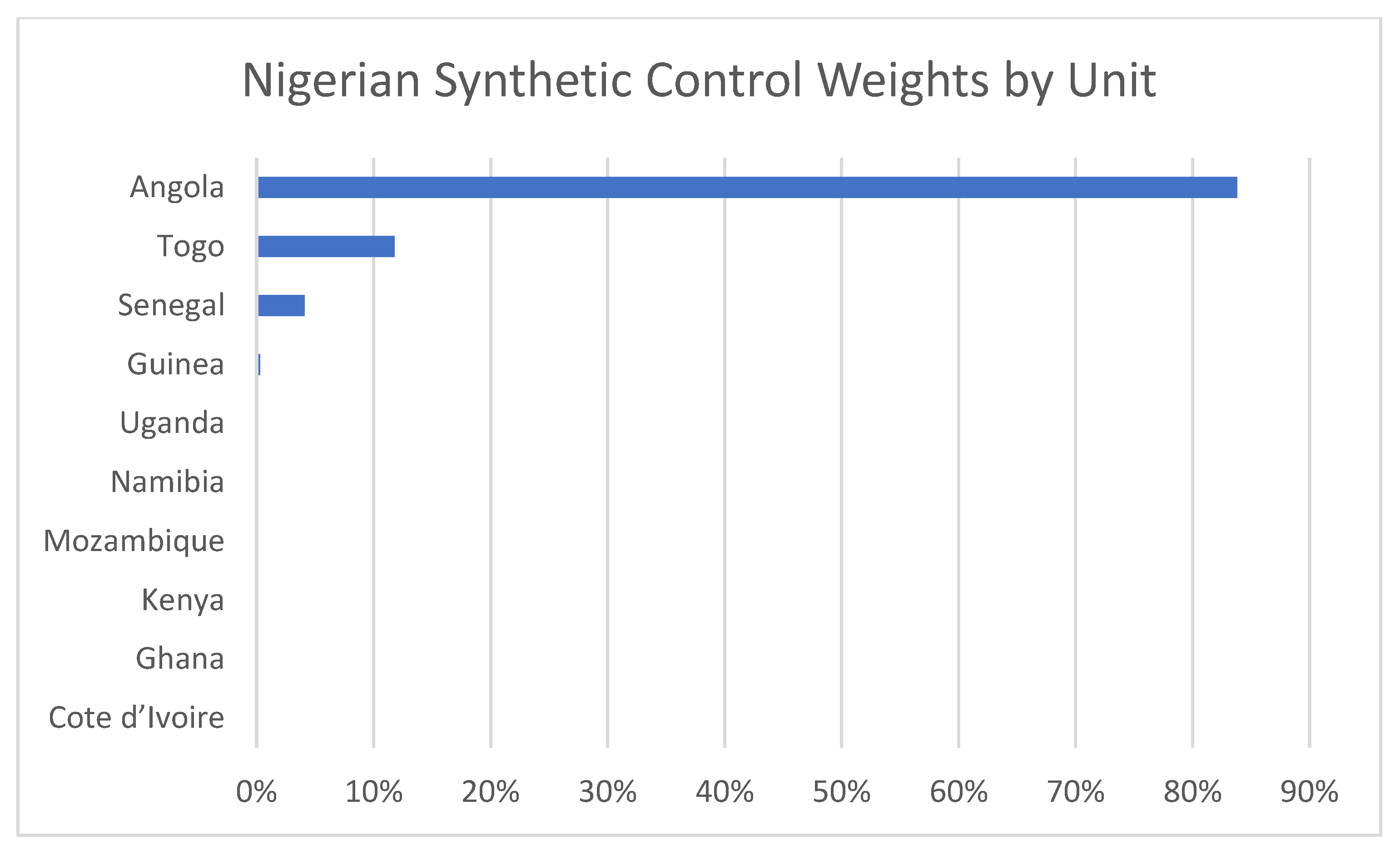

Figure 3, we display the results regarding the weighted averages of the control units to conform the synthetic Nigeria, which out of the ten countries, the software selected four with the following percentage equivalences: Angola 83.8%, Guinea 0.3%, Senegal 4.1%, and Togo 11.8%.

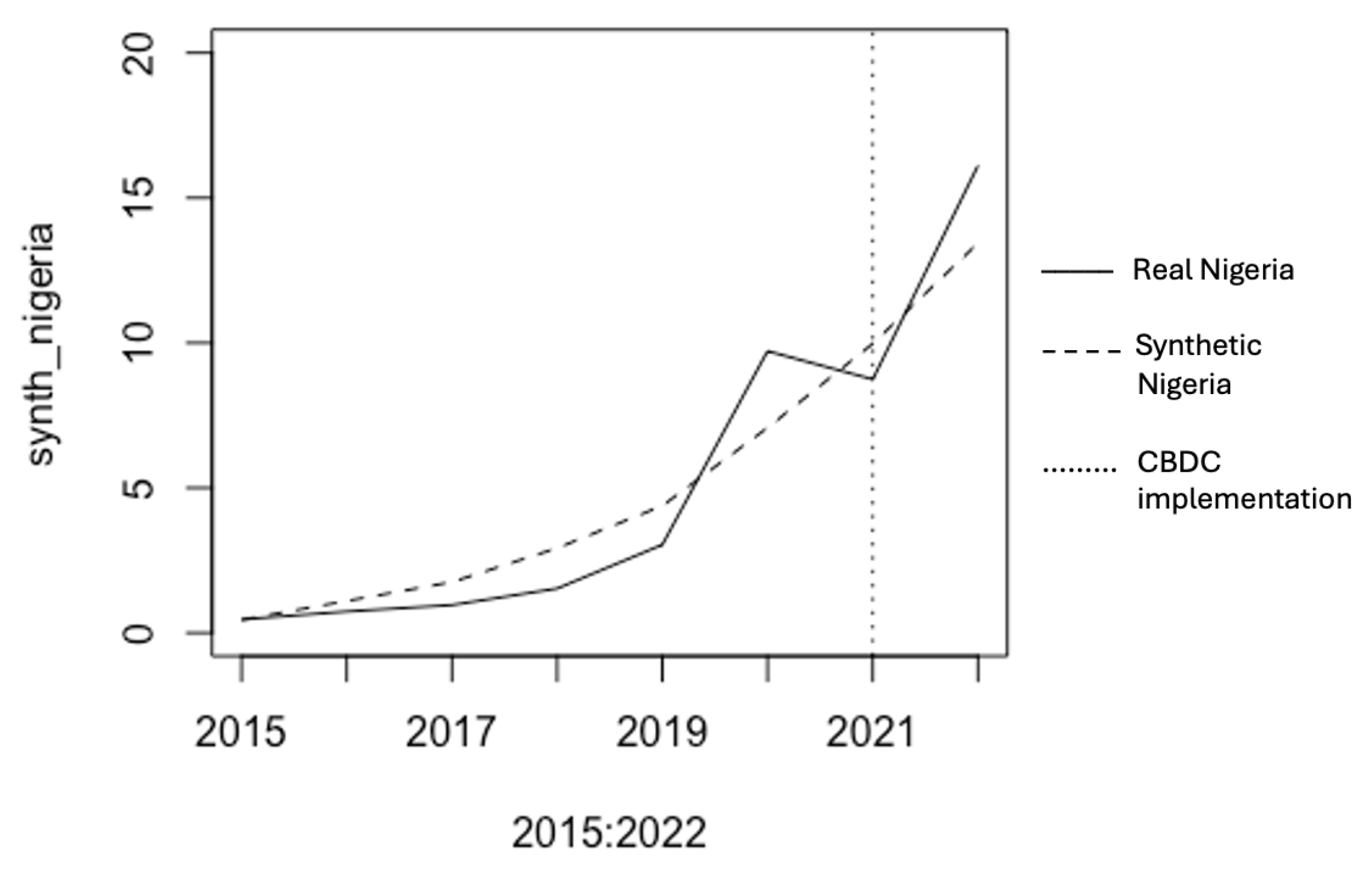

After designing the weighted averages, we continued to elucidate in

Figure 4 the behavior of the dependent variable “value of mobile money transactions % of the GDP” for the synthetic (dashed line) and real Nigeria (solid line) to proceed with the comparison. The Y axis is demarked as the dependent variable, while the X axis has the 2015–2022 timeframe, which shows the intervention year (2021) with a dashed line as well. Furthermore, after observing this illustration, it is possible to argue that both the real and synthetic versions present a similar behavior, enough to give us a counterfactual comparative scenario with a variance in tendency after the treatment date.

Consequently, after displaying the result in

Figure 4 to approach the second research question, “What has been the impact of the eNaira launch on the value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP in Nigeria?”, we argue that Nigeria’s mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP rose significantly compared to the synthetic control group. The upward trend in the solid line for Nigeria contrasts with the slower increase in the synthetic control, implying a notable positive effect of the e-Naira on the dependent variable. Therefore, we accept the second hypothesis: “The eNaira launch in Nigeria should trigger an increase of the value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP, considering its nature and direct relationship with this sort of digital means.” Yet, the results obtained in this empirical analysis section are further scrutinized and discussed in the next section.

5. Results and Limitations

According to the results presented in the previous section, we discuss the following findings: for the Caribbean dataset, four control units (countries) were relevant to the weighted average composition, whereas the other seven were excluded. Similarly, four control units were selected from the twelve countries chosen for the Nigerian dataset. These results are not unusual, as similar patterns can be observed in other SCM analyses, such as those by [

16,

17,

40], where a clear concentration of selected units is evident. In this regard, we observe how the software identifies the most suitable candidates for creating a synthetic version and dismisses others in the process, thereby enhancing the reliability of the analysis from our perspective.

Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that in both cases, there is a high concentration on a single unit. In the case of the Bahamas, St. Lucia represents 67.9% of the weighted average, while for synthetic Nigeria, Angola represents 83.3%. The geographic similarities, access to seaways, sizes, and economic indicators of these countries provide justification for these concentrated outcomes. A final common observation for both cases is that the weighted averages presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 closely followed actual trends during the pre-intervention period, with a clear variance in the post-treatment period, enabling an assessment of the effects under scrutiny. Hence, we consider this a relevant and significant counterfactual study, a conclusion supported by comparing our results with the SCM references published by [

16,

17,

41].

Nevertheless, this concentration of weights on a few individual countries like St. Lucia and Angola in constructing synthetic controls indeed highlights a crucial limitation of SCM. It underscores the need for a balanced representation across units to ensure robustness and generalizability. Addressing this issue could enhance the reliability of the findings and mitigate potential biases arising from such a high concentration on specific units. However, to reach this confidence point, we need to wait for more data, both in terms of time and more similar control countries in the region and across the world, to conduct this comparative analysis again.

For the Bahamas, we confirmed the hypothesis that the introduction of the SandDollar had a negative effect on the dependent variable “outstanding loans from commercial banks as a percentage of the GDP”. Specifically, the goal was to determine whether the implementation of a direct CBDC could create an initial liquidity risk, leading to a decrease in commercial bank loans. Given that the Bahamas’ CBDC operates under a direct model, as discussed in the literature review, we found evidence suggesting a potential “deposit substitution risk”.

Similarly, in the case of Nigeria, we accepted the hypothesis that the eNaira has led to an increase in the “value of mobile money transactions as a percentage of the GDP”. The counterfactual comparison indicates that Nigeria’s CBDC has contributed to the greater use of mobile money (MM) in terms of the GDP, despite the limited expansion of the eNaira. In this sense, CBDCs could promote MM utilization, potentially improving traditional banking penetration and generating positive effects on electronic and international trade [

41].

Additionally, we acknowledge the limitations presented by official statistics on eNaira usage, which indicate that 98.5% of accounts have never been used. Moreover, it has been reported that “the average value of eNaira transactions has been 923 million naira per week, representing only 0.0018 percent of the average M3 during this period, with an average transaction value of 60,000 naira” [

7]. These figures suggest that, in the case of Nigeria, the current transaction volume may not yield a significant long-term impact. Future CBDC implementations should be analyzed to identify patterns that may provide further insights into the broader effects of digital currencies. Hence, the above mentioned reduced public acceptance of eNaira until now forces us to nuance the positive effect of CBDCs on MM use. Anyhow, central banks should coordinate their strategies with digital money providers to ensure a more effective implementation of CBDCs.

While the SCM provides a structured framework for estimating the impact of Nigeria’s eNaira implementation, several limitations apply in this context. First, the analysis is constrained by a short post-treatment period since 2022, which limits insights into longer-term effects. Second, Nigeria may differ substantially from the control units in unobserved ways.

The application of the SCM to assess the impact of CBDCs also embraces challenges such as the assumption that interference between units may be violated, as Caribbean and African economies often share financial and economic ties among themselves, leading to potential spillover effects that bias estimates. Additionally, the presence of structural breaks during the pandemic period complicates the isolation of the CBDCs’ true impact, as deviations in outcomes may stem from broader economic disruptions rather than the intervention itself. Finally, it is important to note that a deeper understanding of the topic will only be possible with more time following CBDC implementation. The full impact of CBDCs on the landscape can only become clearer with broader acceptance in daily transactions, which we acknowledge causes this analysis to be constrained by a short post-treatment period, which limits insights into longer-term effects.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In conclusion, both hypotheses were accepted. The SCM analysis determined that, in the first case, the introduction of the SandDollar led to a decrease in outstanding loans from commercial banks in the real Bahamas compared to its synthetic counterpart. Regarding the second research question, Nigeria’s post-intervention period exhibited a higher percentage of mobile money transactions relative to the GDP in real Nigeria than in its synthetic version.

These results support the claim that direct CBDCs are more likely to create “deposit liquidity risks”, as observed in the Bahamas, where the SandDollar operates under this model. In contrast, the eNaira in Nigeria, due to its digital nature, appears to have positively influenced mobile money usage, as expected. Moreover, the Nigerian central bank’s objectives for developing the eNaira seem to align well with the broader goals of digital financial alternatives.

Consequently, we conclude that in Nigeria, the introduction of the CBDC has led to a positive outcome, promoting the use of mobile money (MM) and contributing to an improvement in FI. Conversely, in the Bahamas, the introduction of the CBDC appears to have reduced loan issuance, increasing liquidity risks within the financial system. Hence, central banks must exercise caution when implementing a new CBDC. Private intermediation of future CBDCs could potentially mitigate liquidity risks and reduce the associated costs of this monetary tool. It is crucial for central banks to recognize that whereas CBDCs offer benefits for FI, these advantages can be undermined by financial instability risks. Therefore, future CBDC implementations should address this concern and be designed to minimize financial instability stemming from liquidity risks. However, as explained in the previous section, the limited time span as well as data limitations in some countries suggest that we should nuance the conclusions we have arrived at.

Finally, for future research, we recommend analyzing the impacts of CBDCs on interest rates, outstanding deposits, mobile money accounts, traditional bank accounts, and credit cards to gain a better understanding of their effects on other related areas. To identify patterns that more clearly explain the impacts of CBDCs, further analyses with additional data and from diverse regions should be conducted to assess the robustness of the results in different scenarios. Additionally, the macroeconomic shifts since the COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced certain behaviors and indicators, potentially affecting the results. Thus, it would be prudent to revisit this research later to verify and contrast the findings, while also approaching the topic from diverse areas such as a systematic risk analysis that scrutinizes the topic beyond this empirical emphasis, considering internal and external aspects that might influence the results obtained.