Modification of Cantor High Entropy Alloy by the Addition of Mo and Nb: Microstructure Evaluation, Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties, and Sliding Wear Response Assessment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure Assessment

3.1.1. XRD Analysis

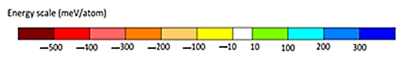

3.1.2. Microstructural Analysis and Parametric Model Assessment

3.1.3. Possible Solidification Sequence

- At the initial stages of solidification, upon cooling, Mo is the element with the highest melting point and as such, drives the solidification process. By combining it with Cr, it forms the primary BCC solid solution phase, which also contains considerable amounts of the other elements being dissolved within it.

- Once the primary phase is formed, the last to solidify the liquid forms the FCC phase.

- Caution should be taken as potential σ-sigma phase formation may also take place, which is, however, difficult to be ascertained through SEM-EDS analysis.

- Nb and Cr seem to control the initial stages of solidification. The primary light phase, according to the EDS analysis, is rich in Nb and Cr with their relative ratio of almost 2:1. Nevertheless, the overall actual composition of the alloy (Table 1) indicates Nb and Cr at a ratio of almost 1:2. It is thus obscure to expect the formation of a Nb rich phase in a system where Cr dominates. Nevertheless, the Cr-Nb phase diagram (Figure 5) [58] may enlighten this grey zone and assist in the solidification of the primary phase. According to the phase diagram, for the relative overall composition of the system where the ratio of Nb to Cr is 1:2, the Laves phase C14 of a cubic crystal structure and with a stoichiometry of Cr2Nb can be formed. It was also interesting to note that from both sides of the Laves phases, a gap in the BCC structure also existed, the presence of which is very crucial. Based on these observations, it can be proposed that the solidification of the primary phase commences with the formation of C14 Laves. Once the C14 phase is formed, it locally depletes the remaining melt form Cr, and as such, it may shift the composition to the right area of the Laves region and upon temperature decrease, the system can be located within the BCC phase area where a BCC phase rich in Nb can be formed. This scenario of the formation of C14 and BCC phases is in agreement with the data presented in the XRD analysis.

- Once the primary phase is formed, the remaining melt seems to follow the postulates of He et al. [48] and behaves as a eutectic system with FCC and C15 Laves as the involved phases. As the temperature decreased, the established undercooling conditions led to the formation of the first eutectic structure, which was fine. As the development of the eutectic structure proceeded due to recalesence and the related heat release, the kinetics of the eutectic development became slower and as such, the eutectic gradually obtained a coarser structure. At the very last stages of the eutectic solidification, the kinetics were significantly retarded and the characteristic lamellae morphology vanished, giving space to more independent decoupling growth of the involved phases. Similar observations can be found in other works by Karantzalis and co-workers [49,50,51].

3.2. Nanoindentation Based Mechanical Property Assessment

Basic Mechanical Property Calculation

- (1)

- Modulus of elasticity (Eit): It can be seen that there was a slight increase in Eit after the modification of the basic Cantor alloy by Mo and Nb. More specifically, the Eit values were 200 ± 7, 213 ± 10, and 230 ± 10 for the plain Cantor alloy, the Mo modified system, and the Nb modified system, respectively. A possible explanation for this even slight increase can be associated with the microstructure and the involved phases in each case. By recalling the observations in the microstructure session, the plain Cantor alloy is a single-phase FCC solid solution with a lattice distortion δ value of 3.26, as calculated by the various parametric models. Lattice distortion mirrors the stress field experienced within the lattice and as such, can be associated with the modulus of elasticity measured in each case. The modification of the basic alloy by the addition of Mo led to phase segregation and the presence of two main phases. As shown in Table 3, the phases that were formed in this system had δ values of 3.80 (primary phase) and 3.40 (secondary phase or matrix). The nano-indentation tests were randomly performed on the specimen surface and as such, the calculated values were the average of the contribution of both segregated phases. Both the δ values of these phases were slightly higher than that of the plain Cantor alloy and as such, their overall contribution provided a δ value higher than the monolithic alloy, resulting in a slightly higher Eit value (213 GPa). The same approach also stands for the Nb modified alloy. The situation was even more intensive as the microstructure consisted of various segregated phases with their δ values ranging from 3.83 up to 6.60. These values were even higher and as such, their overall contribution resulted in an even higher average δ value, which was finally depicted by an even higher Eit value (230 GPa). Similar observations can also be found in other experimental efforts [29,59,60].

- (2)

- Hardness HV: Table 3 clearly shows that the modification of the monolithic Cantor alloy by Mo and Nb led to a significant alteration in the initial hardness HV. More specifically, the HV values were found to be 271 ± 10, 468 ± 30, and 490 ± 35. It can also be observed that the hardness alterations were by far more significant than the modulus Eit. Since hardness is considered to be the resistance of the system to plastic deformation, this means that the modification by Mo and Nb caused a significant negative effect on the dislocation mobility and plastic deformation, leading to a significant increase in the hardness values. The reasons for such an increase can be as follows: (a) Lattice distortion: The higher the lattice distortion, the higher the stress field within the lattice, and the more restricted the dislocation movement. (b) Multiple phases of different crystal structure: The Cantor alloy is an FCC alloy whereas the Mo modified system, according to both the XRD and the SEM analyses, apart from FCC, also contained the BCC and σ phases, which by nature exhibit low dislocation mobility and lower plastic deformation. This trend becomes more severe in the case of the Nb modified system, where additionally to the previous, intermetallic phases may also being present. (c) Increase of phase and grain boundaries: By recalling the microstructures of the examined system, it was observed that from the simple one phase grains of the monolithic Cantor alloy, at least two segregated phases where observed in the case of the Mo modified alloy, whereas in the case of the Nb addition, the microstructure became even more complicated with the presence of primary phases and eutectic morphologies. Thus, a sequence of the progressive development of more complicated microstructures associated with a progressive formation of more phase and grain boundaries was observed. This extensive boundary network also constitutes significant obstacles to the dislocation movement, and therefore to plastic deformation. All of these remarks are also in agreement with other research works [23,24].

- (3)

- nit ratio: The nit ratio, by definition, follows the trend of the hardness values. Since the hardness is increased by the addition of Mo and Nb (i.e., the resistance in plastic deformation is accordingly increased), the energy absorbed in the elastic region is increased (i.e., the nit ratio is altered in the same manner as the hardness).

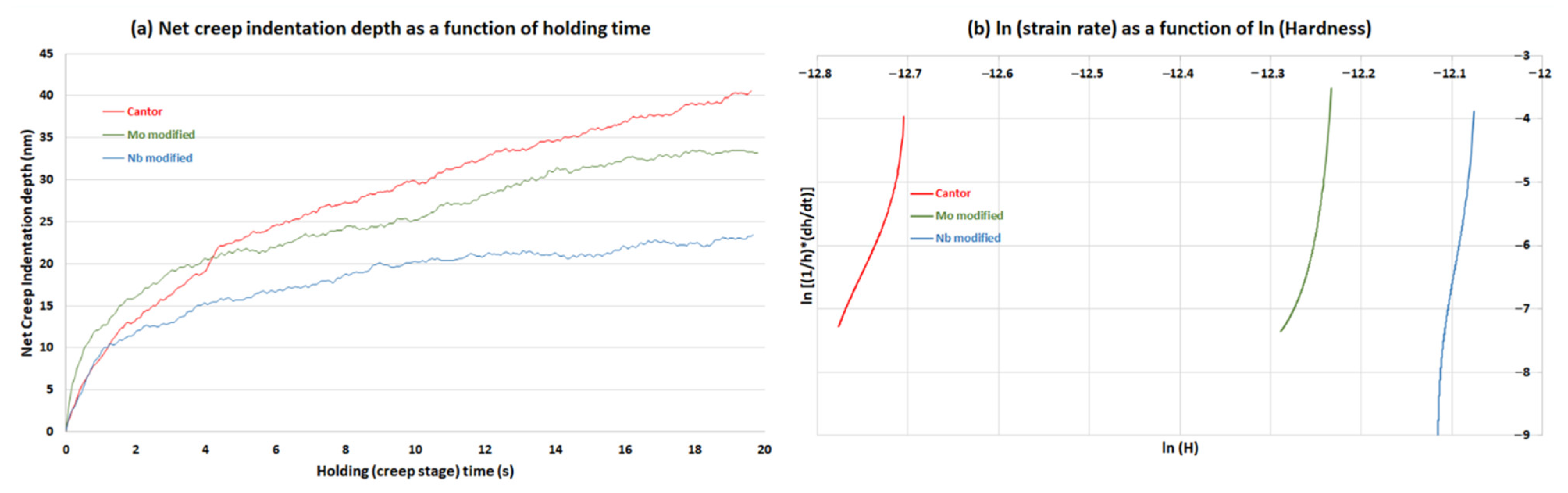

3.3. Creep Assessment

3.3.1. Calculation Frame

3.3.2. Creep Results

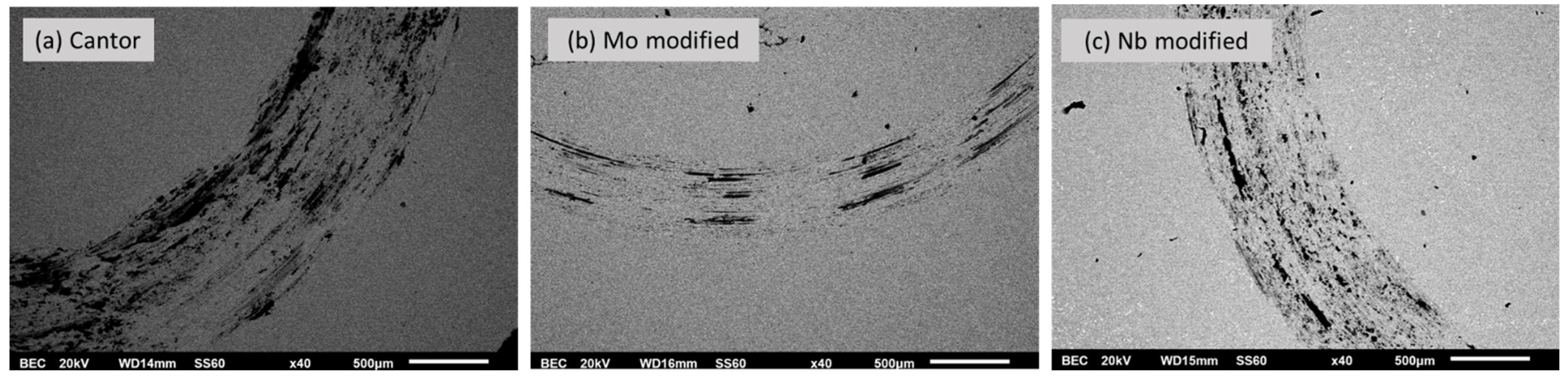

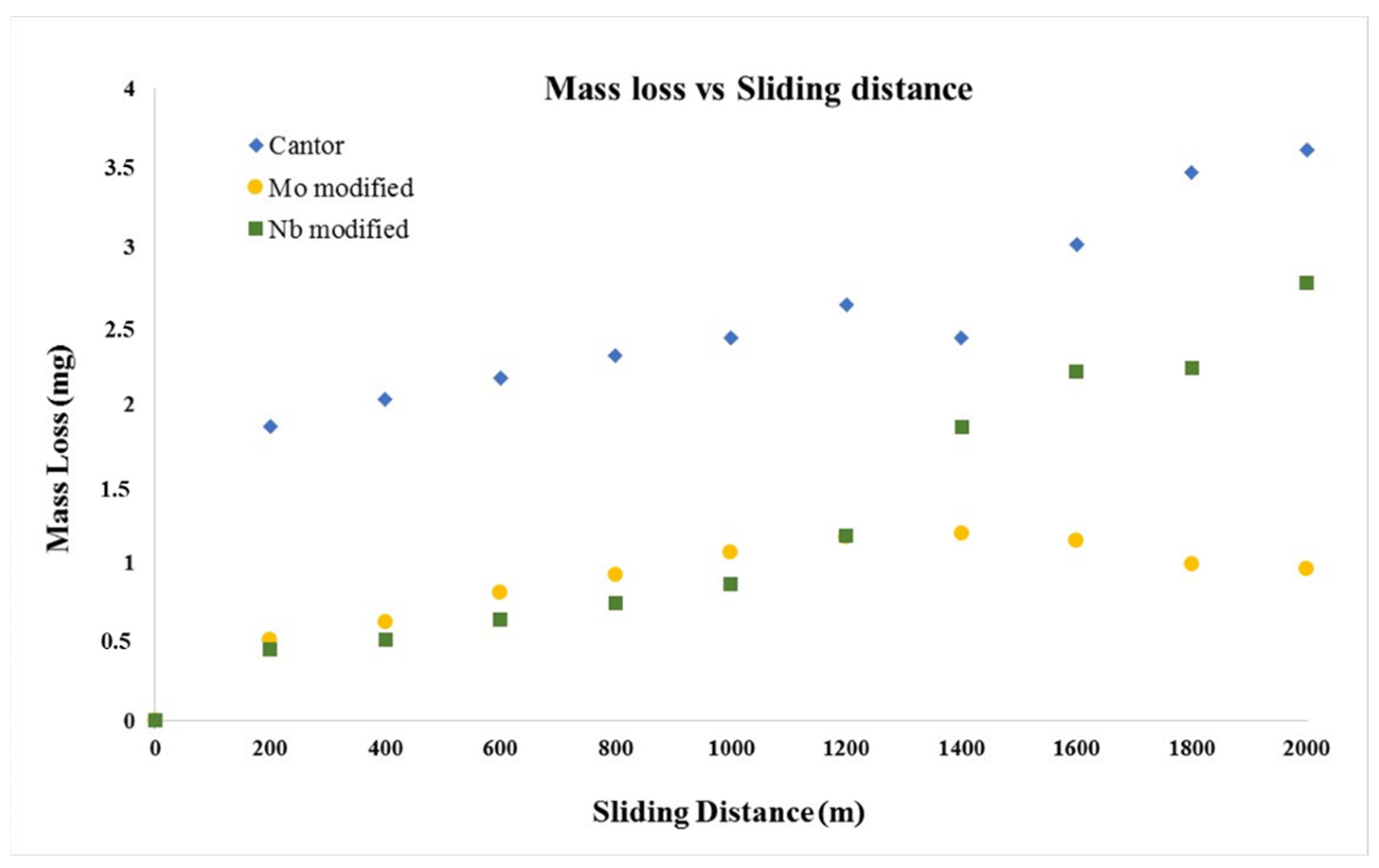

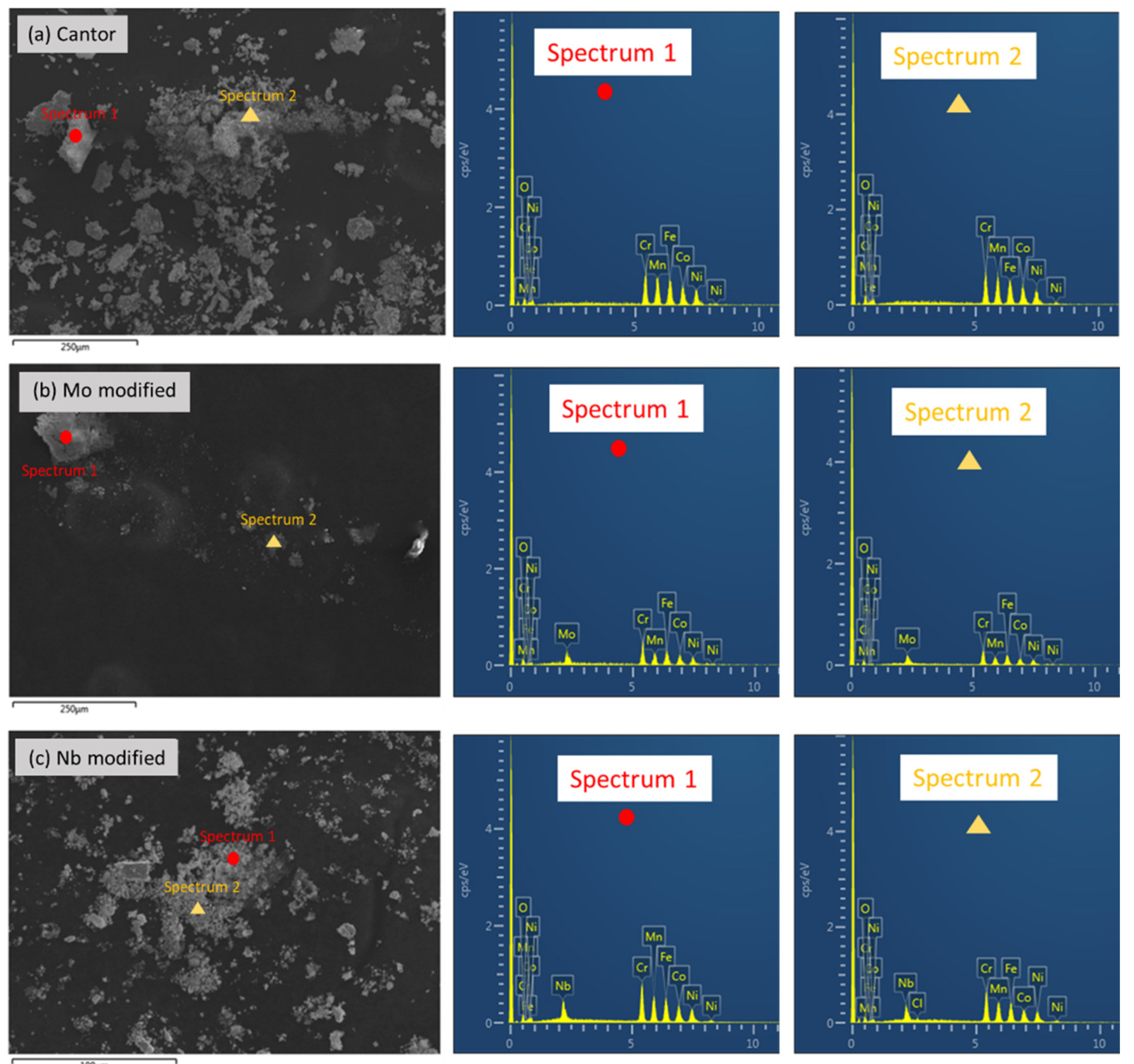

3.4. Sliding Wear Response

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Dlouhý, A.; Pradeep, K.G.; Kuběnová, M.; Raabe, D.; Eggeler, G.; George, E.P. Decomposition of the single-phase high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi after prolonged anneals at intermediate temperatures. Acta Mater. 2016, 112, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, X.; Zeng, M.; Liu, K.; Fu, L. Phase engineering of high-entropy alloys. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Su, H.; Zhou, H.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Fu, H. Unique strength-ductility balance of AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high entropy alloy with ultra-fine duplex microstructure prepared by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 111, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.W.; Lu, Y.S.; Lai, Z.H.; Yen, H.W.; Lee, Y.L. Comparative corrosion behavior of Fe50Mn30Co10Cr10 dual-phase high-entropy alloy and CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 842, 155824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.P.; Wang, G.J.; Ma, Y.J.; Cao, Z.H.; Meng, X.K. High hardness dual-phase high entropy alloy thin films produced by interface alloying. Scripta Mater. 2019, 162, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.L.; Zheng, Z.Q.; Guo, S.W.; Huang, P.; Wang, F. Ultra-strong nanostructured CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmir, H.; He, J.; Lu, Z.; Kawasaki, M.; Langdon, T.G. Effect of annealing on mechanical properties of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy processed by high-pressure torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 676, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuh, B.; Mendez-Martin, F.; Völker, B.; George, E.P.; Clemens, H.; Pippan, R. Mechanical properties, microstructure and thermal stability of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2015, 96, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foley, D.L.; Huang, S.H.; Anber, E.; Shanahan, L.; Shen, Y.; Lang, A.C.; Barr, C.M.; Spearot, D.; Lamberson, L.; Taheri, M.L. Simultaneous twinning and microband formation under dynamic compression in a high entropy alloy with a complex energetic landscape. Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P.; Tsai, Y.T.; Chen, Y.W.; Chen, P.J.; Chiu, P.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Yeh, J.W.; Yang, J.R. High-entropy CoCrFeMnNi alloy subjected to high-strain-rate compressive deformation. Mater. Charact. 2019, 147, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Dlouhý, A.; Somsen, C.; Bei, H.; Eggeler, G.; George, E.P. The influences of temperature and microstructure on the tensile properties of a CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5743–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- An, X.; Wang, Z.; Ni, S.; Song, M. The tension-compression asymmetry of martensite phase transformation in a metastable Fe40Co20Cr20Mn10Ni10 high-entropy alloy. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 63, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, A.; Koehler, M.; Catoor, D.; George, E.P.; Keppens, V. Polycrystalline elastic moduli of a high-entropy alloy at cryogenic temperatures. Intermetallics 2015, 58, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaddach, A.J.; Niu, C.; Koch, C.C.; Irving, D.L. Mechanical properties and stacking fault energies of NiFeCrCoMn high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 65, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.T.; Huang, J.C.; Lin, P.H.; Liu, T.Y.; Liao, Y.C.; Jang, J.S.C.; Song, S.X.; Nieh, T.G. Creep of face-centered-cubic {111} and {100} grains in FeCoNiCrMn and FeCoNiCrMn single bond Al alloys: Orientation and solid solution effects. Intermetallics 2018, 103, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siska, F.; Cech, J.; Hausild, P.; Hadraba, H.; Chlup, Z.; Husak, R.; Stratil, L. Twinning in CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy induced by nanoindentation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 784, 139297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.N.; Yoo, B.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, J.I. Indentation creep revisited. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 27, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, S.J. Nanoindentation of coatings. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Henshall, J.L.; Hooper, R.M.; Easterling, K.E. The mechanisms of indentation creep. Acta Metall. Mater. 1991, 39, 3099–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.S.; Long, S.G.; Zhou, Y.C.; Pan, Y. Indentation scale dependence of tip-in creep behavior in Ni thin films. Scr. Mater. 2008, 59, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Feng, Y.H.; Debela, T.T.; Peng, G.L.; Zhang, T.H. Nanoindentation study on the creep characteristics of high-entropy alloy films: Fcc versus bcc structures. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2016, 54, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Song, Y.X.; Ma, Y.; Huang, X.W.; Zhang, T.H. Nanoindentation investigation on the size-dependent creep behavior in a Zr-Cu-Ag-Al bulk metallic glass. Metals 2019, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, P.H.; Chou, H.S.; Huang, J.C.; Chuang, W.S.; Jang, J.S.C.; Nieh, T.G. Elevated-temperature creep of high entropy alloys via nanoindentation. MRS Bull. 2019, 44, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, P.F.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Diao, H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, B.; Chen, P.; Feng, R.; Bai, J.; et al. Nanoindentation creep behavior of an Al0.3CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 5871–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.B.; Shim, S.H.; Lee, K.H.; Hong, S.I. Dislocation creep behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy at intermediate temperatures. Mater. Res. Lett. 2018, 6, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.M.; Chu, M.Y.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, Z.H.; Qiao, J.W. Nanoindentation characterised plastic deformation of a Al0.5CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.T. Nanoindentation characterized initial creep behavior of a high-entropy-based alloy CoFeNi. Intermetallics 2014, 53, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhafez, I.A.; Ruestes, C.J.; Bringa, E.M.; Urbassek, H.M. Nanoindentation into a high-entropy alloy-An atomistic study. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 803, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jang, J.S.C.; Nieh, T.G. Elastic and plastic deformations in a high entropy alloy investigated using a nanoindentation method. Intermetallics 2016, 68, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maier-Kiener, V.; Schuh, B.; George, E.; Clemens, H.; Hohenwarter, A. Insights into the deformation behavior of the CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy revealed by elevated temperature nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 2658–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Xiang, M.; Zhang, D.; Shi, J.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Tang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z.; et al. Mechanical properties of Cantor alloys driven by additional elements: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, N.; Das, S.; Gurao, N.P.; Biswas, K. Effect of Al addition on the microstructural evolution of equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi alloy. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2018, 71, 2749–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Chen, R.R.; Zheng, H.T.; Fang, H.Z.; Wang, L.; Su, Y.Q.; Guo, J.J.; Fu, H.Z. Strengthening FCC-CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloys by Mo addition. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.D.; Luan, H.W.; Liu, X.; Chen, N.; Li, X.Y.; Shao, Y.; Yao, K.F. Microstructures and mechanical properties of TixNbMoTaW refractory high-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 712, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.G.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Nb addition on the microstructure and properties of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 532, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Fu, H.M.; Zhang, H.F.; Wang, A.M.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.Q. Synthesis and properties of multiprincipal component AlCoCrFeNiSix alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 7210–7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.C.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, Q. Effect of aluminum contents on microstructure and properties of AlxCoCrFeNi alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 504, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Chen, D.; Han, B.; Wang, J.; Feng, R.; Yang, T.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, Y.L.; Guo, W.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Outstanding tensile properties of a precipitation strengthened FeCoNiCrTi0.2 high-entropy alloy at room and cryogenic temperatures. Acta Mater. 2019, 165, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, E.; Casagrande, A.; Garzoni, A.; Giovanardi, R.; Veronesi, P. Al, Cu and Zr addition to High Entropy Alloys: The effect on recrystallization temperature. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 941, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campari, E.G.; Casagrande, A.; Colombini, E.; Gualtieri, M.L.; Veronesi, P. The effect of Zr addition on melting temperature, microstructure, recrystallization and mechanical properties of a Cantor high entropy alloy. Materials 2021, 14, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Mao, A.; Wang, L.; Song, G.; He, Y. Microstructure and nanoindentation creep behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findik, F. Latest progress on tribological properties of industrial materials. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Haghdadi, N.; Shamlaye, K.; Hodgson, P.; Barnett, M.; Fabijanic, D. The sliding wear behaviour of CoCrFeMnNi and AlxCoCrFeNi high entropy alloys at elevated temperatures. Wear 2019, 428, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shun, T.T.; Chang, L.Y.; Shiu, M.H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of multiprincipal component CoCrFeNiMox alloys. Mater. Char. 2012, 70, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Dang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.T. Designing eutectic high entropy alloys of CoCrFeNiNbx. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 656, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiou, C.; Giorspyros, K.; Georgatis, E.; Poulia, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Karantzalis, A.E. NiAl-Cr-Mo-W high-entropy systems: Microstructural verification, solidification considerations and sliding wear response. Metallog. Microstr. Anal. 2022, 11, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiou, C.; Giorspyros, K.; Georgatis, E.; Poulia, A.; Karantzalis, A.E. NiAl-Cr-Mo medium entropy alloys: Microstructural verification, solidification considerations, and sliding wear response. Materials 2020, 13, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiou, C.; Giorspyros, K.; Georgatis, E.; Karantzalis, A.E. Microstructural verification of the theoretically predicted morphologies of the NiAl-Cr pseudo-binary alloy systems and NiAl-Cr eutectic structure modification by Mo addition. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Lin, J.P.; Chen, G.L.; Liaw, P.K. Solid solution phase formation rules for multi-component alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.T. Atomic-size effect and solid solubility of multicomponent alloys. Scr. Mater. 2015, 94, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Ng, C.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.T. Effect of valence electron concentration on stability of fcc or bcc phase in high entropy alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.B. A new thermodynamic parameter to predict formation of solid solution or intermetallic phases in high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 658, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Troparevsky, M.C.; Morris, J.R.; Kent, P.R.C.; Lupini, A.R.; Stocks, G.G. Criteria for predicting the formation of single-phase high-entropy alloys. Phys. Rev. X 2015, 5, 011041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phase Diagram. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/catcalcphase/metal/cr/cr-nb (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, Y.V.; Golubenko, A.A.; Dub, S.N. Indentation size effect in nanohardness. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 7480–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantzalis, A.E.; Mathiou, C.; Kyrtsidou, K.; Georgatis, E. Primary nano-indentation assessment of low entropy NiAl-Cr alloys. SOJ Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Karantzalis, A.E.; Sioulas, D.; Poulia, A.; Mathiou, C.; Georgatis, E. A first approach on the assessment of the creep behavior of MoTaNbVxTi high entropy alloys by indentation testing. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tan, J.; Li, C.J.; Qin, X.M.; Guo, S.F. Enhanced creep resistance of Ti30Al25Zr25Nb20 high-entropy alloy at room temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 885, 161038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.F.; Feng, S.D.; Xu, G.S.; Guo, X.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, W.; Qi, L.; Li, G.; Liaw, P.K.; Liu, R.P. Room-temperature creep resistance of Co-based metallic glasses. Scr. Mater. 2014, 90, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, J.D.; Xuan, F.Z.; Liu, C.J.; Chen, B. Modelling of cavity nucleation under creep-fatigue interaction. Mech. Mater. 2021, 156, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.D. Friction and Wear; Academic Press: London, UK, 1980; pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mavros, H.; Karantzalis, A.E.; Lekatou, A. Solidification observations and sliding wear behavior of cast TiC particulate-reinforced AlMgSi matrix composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2012, 47, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.P. The delamination theory of wear. Wear 1973, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.P. An overview of the delamination theory of wear. Wear 1977, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archard, J.F.; Hirst, W. The wear of metals under unlubricated conditions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1956, 236, 397–410. [Google Scholar]

- Glascott, J.; Stott, F.H.; Wood, G.C. The effectiveness of oxides in reducing sliding wear of alloys. Oxid. Met. 1985, 24, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, F.H.; Wood, G.C. The influence of oxides on the friction and wear of alloys. Tribol. Int. 1978, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition at.% | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alloy | Cantor | Cantor + Mo | Cantor + Nb | |||||||||||||||

| Phase | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Mo | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Nb | ||

| Nominal | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 24.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 8.0 | 24.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 8 | |

| Actual | 20.1 | 19.2 | 20.5 | 20.8 | 19.4 | 24.7 | 15.3 | 17.5 | 17.8 | 16.8 | 7.9 | 24.6 | 15.7 | 17.0 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 9.1 | |

| Matrix | 25.1 | 14.1 | 19.0 | 18.3 | 17.4 | 6.1 | ||||||||||||

| Primary phase | 29.3 | 12.9 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 11.8 | 13.5 | ||||||||||||

| Light phase | 20.4 | 5.9 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 8.4 | 40 | ||||||||||||

| Gray phase | 21.2 | 14.9 | 15.1 | 17.9 | 15.1 | 15.8 | ||||||||||||

| Dark phase | 26.2 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 17.9 | 17.1 | 3.38 | ||||||||||||

| Parametric Models | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alloy | Cantor | Cantor + Mo | Cantor + Nb | |||||||||||||||

| Phase | Nominal | Actual | Nominal | Actual | Matrix | Primary | Nominal | Actual | Light Phase | Gray Phase | Dark Phase | |||||||

| Model | ||||||||||||||||||

| δ | 3.27 | 3.22 | 3.65 | 3.58 | 3.40 | 3.79 | 4.58 | 4.69 | 6.60 | 5.40 | 3.83 | |||||||

| ΔSmix [J/K mol] | 13.38 | 13.38 | 14.52 | 14.51 | 14.33 | 14.44 | 14.52 | 14.58 | 13.20 | 14.82 | 14.03 | |||||||

| ΔHmix [kJ/mol] | −4.16 | −4.09 | −3.96 | −3.99 | −4.01 | −3.51 | −8.06 | −8.56 | −16.44 | −11.43 | −5.80 | |||||||

| ΔG | −31.76 | −31.73 | −35.59 | −35.62 | −35.05 | −35.15 | −39.52 | −40.33 | −49.33 | −44.53 | −35.65 | |||||||

| VEC | 8 | 8 | 7.68 | 7.71 | 7.76 | 7.41 | 7.60 | 7.58 | 6.63 | 7.43 | 7.73 | |||||||

| Ω | 5.76 | 5.86 | 6.99 | 6.94 | 6.76 | 8.19 | 3.41 | 3.25 | 1.78 | 2.54 | 4.49 | |||||||

| γ | 1.096 | 1.096 | 1.107 | 1.107 | 1.107 | 1.107 | 1.167 | 1.167 | 1.164 | 1.166 | 1.168 | |||||||

| Tm [K] | 1790 | 1793 | 1905 | 1908 | 1892 | 1994 | 1893 | 1906 | 2218 | 1960 | 1854 | |||||||

| ΔHIM/ΔHmix | 1.66 | 1.65 | 2.35 | 2.29 | 2.13 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.83 | 3.60 | 2.99 | 2.36 | |||||||

| k1cr | 3.30 | 3.34 | 3.80 | 3.78 | 3.71 | 4.28 | 2.36 | 2.29 | 1.71 | 2.02 | 2.79 | |||||||

| Element | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Mo | Nb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | ||||||||

| Cr | 0 | −110 | −8 | 5 | −30 | 42 | −47 | |

| Mn | −110 | 0 | 9 | −19 | −115 | −136 | −153 | |

| Fe | −8 | 9 | 0 | −60 | −97 | −484 | −2505 | |

| Co | 5 | −19 | −60 | 0 | −21 | −52 | −150 | |

| Ni | −30 | −115 | −97 | −21 | 0 | −100 | −316 | |

| Mo | 42 | −136 | −484 | −52 | −100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nb | −47 | −153 | −2505 | −150 | −316 | 0 | ||

| ||||||||

| System | Eit (GPa) | HV | nit (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantor | 200 ± 7 | 271 ± 10 | 11.7 ± 2 |

| Mo modified | 213 ± 10 | 468 ± 30 | 18.6 ± 4 |

| Nb modified | 230 ± 10 | 490 ± 35 | 22.0 ± 7 |

| System | n Extra | n Actual | m Extra | m Actual | Vcr Extra (nm3) | Vcr Actual (nm3) | hcreep (nm) | τmax (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantor | 32 ± 8 | 34 ± 9 | 0.031 ± 0.008 | 0.029 ± 0.009 | 0.196 ± 0.05 | 0.208 ± 0.06 | 38 ± 8 | 0.674 ± 0.05 |

| Mo modified | 53 ± 9 | 63 ± 10 | 0.019 ± 0.007 | 0.018 ± 0.007 | 0.227 ± 0.06 | 0.269 ± 0.07 | 33 ± 10 | 0.960 ± 0.07 |

| Nb modified | 107 ± 12 | 109 ± 12 | 0.0133 ± 0.009 | 0.0115 ± 0.09 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.414 ± 0.07 | 23.5 ± 8 | 1.071 ± 0.09 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karantzalis, A.E.; Poulia, A.; Kamnis, S.; Sfikas, A.; Fotsis, A.; Georgatis, E. Modification of Cantor High Entropy Alloy by the Addition of Mo and Nb: Microstructure Evaluation, Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties, and Sliding Wear Response Assessment. Alloys 2022, 1, 70-92. https://doi.org/10.3390/alloys1010006

Karantzalis AE, Poulia A, Kamnis S, Sfikas A, Fotsis A, Georgatis E. Modification of Cantor High Entropy Alloy by the Addition of Mo and Nb: Microstructure Evaluation, Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties, and Sliding Wear Response Assessment. Alloys. 2022; 1(1):70-92. https://doi.org/10.3390/alloys1010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarantzalis, Alexandros E., Anthoula Poulia, Spyros Kamnis, Athanasios Sfikas, Anastasios Fotsis, and Emmanuel Georgatis. 2022. "Modification of Cantor High Entropy Alloy by the Addition of Mo and Nb: Microstructure Evaluation, Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties, and Sliding Wear Response Assessment" Alloys 1, no. 1: 70-92. https://doi.org/10.3390/alloys1010006

APA StyleKarantzalis, A. E., Poulia, A., Kamnis, S., Sfikas, A., Fotsis, A., & Georgatis, E. (2022). Modification of Cantor High Entropy Alloy by the Addition of Mo and Nb: Microstructure Evaluation, Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties, and Sliding Wear Response Assessment. Alloys, 1(1), 70-92. https://doi.org/10.3390/alloys1010006