1. Introduction

The formation of deformation resistant precipitates from a supersaturated solid solution is one of the most powerful methods of strengthening applied in alloys. The most common mode of precipitation involves the nucleation and growth of individual isolated precipitates that can provide formidable barriers to dislocation motion when shear resistant and closely spaced. When these precipitates form, there is a continuous evolution in their particle size distribution throughout the microstructure, and thus this mode is referred to as continuous precipitation (CP) [

1]. However, another mode of precipitation is also possible. It is observed in over 80 binary systems under particular conditions of supersaturation and temperature [

1,

2]. This mode involves the cellular growth of the precipitating phase, usually as alternating layers with the matrix, behind a migrating high angle boundary (HAGB). At any moment during precipitation, the microstructure can be clearly divided into two regions; one containing precipitate phase and one which is precipitate free. This is known as discontinuous precipitation (DP). Given its morphological similarity to eutectoid transformations, it is often understood on the basis of the same essential mechanisms [

3,

4,

5].

The magnesium–aluminium system is one example of a commercially important alloy type where both CP and DP are observed. Magnesium-aluminium is the basis of the dominant class of AZ magnesium alloys, such as AZ91, where precipitation can occur of a second phase referred to as

, which has an ideal stoichiometric composition Mg

17Al

12. Despite the ability of these alloys to form a volume fraction of precipitate close to 15%, the strengthening response obtained is poor; less than half that achieved in some aluminium alloys that form a much lower fraction of precipitates [

6]. There is thus considerable interest in improving the strengthening response of AZ type alloys during precipitation. One issue that contributes to the poor strengthening response of AZ alloys to ageing is the formation of DP. The DP lamellae are usually widely spaced and offer poor barriers to dislocation motion. In addition, since DP and CP are in competition, when DP forms, it suppresses CP, mainly by consuming the supersaturated matrix and reducing the volume available to CP [

7]. Therefore, it is considered desirable to suppress DP and promote CP, and achieving this may lead to better strengthening behaviour in a temperature range that is amenable to commercial heat treatment (for example <24h ageing time).

One method that can suppress DP and promote CP, as well as providing direct strengthening, is to perform deformation prior to precipitation. It has been demonstrated experimentally for Mg–Al under one set of conditions that deformation appears to slow down the formation of DP [

8]. In this work, cold rolling to a heavy reduction of 30% was found to almost completely eliminate DP for an ageing condition that would otherwize produce a fully DP microstructure [

8].

However, in general, it is known that pre-deformation can have either an accelerating or retarding effect on DP [

8]. This is because DP is in competition with CP, and deformation can influence the balance of this competition. Recent studies have demonstrated that severe plastic deformation (SPD) [

9,

10] or cold compression [

11] can accelerate and refine the formation of continuous precipitates in Mg–Al. However, even when very high cumulative strains are achieved during SPD, local regions of DP are still observed. Indeed, since DP occurs behind a migrating HAGB, the factors that promote boundary motion, such as a stored energy gradient, are also expected to promote DP and lead to a coupling between recrystallisation and discontinuous precipitation [

9].

The purpose of the present work is to extend a model previously developed for competitive CP and DP in Mg–Al alloys to include the effect of pre-deformation. This model is then used to explore the possible interactions between these two precipitation modes to determine the mechanisms by which deformation can influence the fraction of each. A subset of new experiments from a wider study are used to test the model and demonstrate some of the complex interactions between deformation, twinning, and DP/CP that can occur.

2. Method

A small number of experimental results from a wider study are chosen here to illustrate important aspects of the interaction of DP and CP with deformation. The material used is commercial AZ80 alloy (nominal composition range 7.8−9.2Al–0.2−0.8Zn–0.12−0.5Mn wt%, balance Mg), provided as direct chill–cast ingot by Luxfer MEL Technologies, Manchester, UK. The as cast material was homogenised at 400

C for 24 h using an argon gas furnace, and then hot rolled on a laboratory mill at 400

C to a total reduction of 80%. This material was then solution treated for 1 h at 420

C, leading to a refined equiaxed grain structure with a basal texture and dissolution of the Al and Zn. Finally, cold rolling (at room temperature) was applied in 5 equi-strain passes to 5% total reduction. Greater cold rolling reductions were also investigated, but it was found that even a 5% reduction produced the desired effect in suppressing DP whilst facilitating subsequent analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD). Precipitation heat treatment was carried out on both cold rolled and solution treated material for 16 h at 220

C. This temperature was chosen since it corresponds to a condition where DP is usually dominant, enabling the effect of deformation on DP precipitation to be most clearly seen [

8].

Specimens for optical and scanning electron microscopy (OM and SEM) were prepared with standard metallographic methods using acetic glycol etchant. Specimens for EBSD were not etched but subject to further polishing using a Leica EM RES102 Ion Beam Milling System operated at a current of 2.8 mA and a voltage of 7 kV, using two cleaning steps: firstly with a beam angle of 12.5 for 10 min and secondly at an angle of 5 for 10 min.

Analysis of DP fraction was performed by manually identifying DP regions and determining area fractions using ImageJ. SEM was performed using Tescan Mira 3 FEGSEM, operated at 10 kV with a working distance of 20 mm. Backscattered imaging mode was used to provide atomic number contrast. EBSD was performed using an FEI Magellan FEG-SEM equipped with an OI NordlysS EBSD detector and AZtec software, using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. The step size used for the EBSD scans was 0.75 m. Maps were processed in AZtec Crystal and are presented in inverse pole figure colouring (plotting the normal direction).

3. Modelling

CP and DP are in competition, and thus promotion of one precipitation mode will tend to suppress the other. To understand this competition, a classical model was previously developed that allows the two mechanisms to occur simultaneously and naturally predicts their interactions based on the competition for solute, free volume, and boundary pinning effects. This model has been adapted in the present work to also include the effect of deformation on both CP and DP. Full details of the model as applied to non-deformed material are given elsewhere [

7], but its essential features are summarized below.

In the present work, this model was modified in two ways to include the effect of deformation. Firstly, the dislocations introduced by deformation are known to provide potent nucleation sites for the formation of continuously nucleated

phase. This effect is accounted for by modifying the energy barrier for nucleation

and the nucleation site density

. An approximate estimate for appropriate values for these parameters comes from the work of Ma et al. [

9]. They measured both dislocation density and

particle number in a heavily deformed AZ80 alloy and compared this with an identically heat treated non-deformed case. For a measured dislocation density in the deformed state of 1.4 ± 0.2 ×

m

, they recorded a 10 fold increase in the particle number density during the early stages of ageing. Assuming coarsening was negligible, this implies a 10 fold increase in nucleation rate due to deformation. This was used to estimate the modification factor

for heterogeneous nucleation, giving a value

. Note that in this case,

should be considered as a fitting parameter that gives approximately the correct accelerating effect for heterogeneous nucleation on dislocations, rather than being ascribed any physical significance.

Precipitate growth will also be influenced by formation on dislocations. However, the observation that deformation leads to a much higher number density of smaller preciptiates suggests this effect is less strong than that on nucleation. This is probably because once sufficient nucleation and initial growth has occurred, it is diffusion through the matrix to the precipitate and dislocation line that becomes rate limiting, rather than diffusion along the dislocation. Furthermore, the precipitates retain their habit plane even when precipitating on dislocations, and do not grow preferentially along the dislocation line, which limits the effect that dislocation pipe diffusion can have on their growth. For these reasons, the effect of dislocations on the precipitate growth rate was ignored. As demonstrated later, the predicted change in precipitate size associated with introducing additional nucleation sites is consistent with that observed experimentally, suggesting this is a reasonable assumption.

Deformation will also influence DP. The DP growth front is a high angle grain boundary, migrating into supersaturated matrix. The migration of the boundary is driven by the chemical free energy change on transformation of supersaturated

to

, but in deformed material it will be additionally driven by the stored energy in the deformation structures. DP is therefore a coupled process of precipitation and recrystallization. As discussed by Ma et al. [

9], the driving force due to the supersaturation is typically much greater than that due to the dislocation substructures, and this can lead to recrystallization and DP occurring under conditions for which recrystallization alone would not occur. A full physical model for the combined DP and recrystallization process is highly complex and beyond the scope of the present work. This is because such a model would need to consider the simultaneous effects of the evolving supersaturation (due to CP) and evolving stored energy in the deformation structure due to recovery processes. Instead, in the present work, a simple approach is used that captures the effect that the additional driving force due to the deformation structure will have on the DP boundary migration velocity. The boundary velocity is the product of the mobility and driving pressure. Assuming the mobility is unchanged with deformation (which is reasonable since it is controlled by diffusion and curvature at the DP growth front), the boundary velocity may be written as:

where

is the pressure on the boundary arising from the energy in the deformation structure,

is the pressure on the boundary arising from the supersaturation, and

is the DP front growth velocity due to supersaturation alone (i.e., in the absence of deformation effects). The pressure on the boundary due to the energy stored in the dislocations is given by:

where

G is the shear modulus,

b the dislocation Burgers vector (

nm [

6]) and

the dislocation density. During the early stages of DP, the DP growth front will be highly curved, and this leads to a retarding pressure due to the surface tension effect. As will be shown later, this pressure is only significant when the DP region is very small, but it does become important when considering what happens in the early stages of DP growth. For the mean field model discussed here, this effect is ignored (since it is implicitly captured by the fitting of the DP nucleation rate).

Crystal Plasticity Modelling

In addition to the mean field effect of deformation, captured in the model described above, it is important to recognise that in magnesium, strain is often highly non-uniformly distributed within the microstructure. For example, digital image correlation (DIC) techniques commonly reveal that local strain concentrations, which usually occur in regions close to grain boundaries, can exceed 30 times the macroscopically applied strain [

13]. As will be demonstrated later, this heterogeneity of deformation can play an important role in determining the local behaviour of a region with regard to precipitation. It is difficult to explore this experimentally for a rolled sample, but a good estimate of the non-uniform strain distribution can be obtained from a full field crystal plasticity model [

14].

In the present work, the DAMASK crystal plasticity framework was used to perform simulations of the strain distribution obtained after the cold rolling step. Details of this model, and its application to magnesium alloys, are given elsewhere [

14]. Simulations were run for a 3-dimensional ensemble containing 125 grains within a

grid. The grains were produced by Voronoi tessellation from random seeds, and the orientation of each grain was assigned by random sampling of the experimentally determined texture prior to cold rolling. This gives a reasonable representation of the true microstructure prior to the cold rolling step, and importantly captures the effect of the experimentally measured texture on strain localization.

The load was applied assuming plane strain compression, which is reasonable for rolled material away from the sheared surface layers. A strain rate of 1s

was assumed, which is a reasonable estimate for laboratory cold rolling. The single crystal constitutive response was modelled using a phenomenological power law that accounts for all of the slip and twinning systems that are known to be active in magnesium. Further details of this law and the parameters used as inputs to the constitutive response are given in [

14].

No attempt was made to refine the fitting parameters in the single crystal power law since the purpose of the present work was not to accurately predict the stress-strain response of the material, but rather to understand the extent of strain heterogeneity that would be expected after rolling. Similarly, since the geometry of twinning (i.e., the formation of multiple lenticular regions of sheared material of different orientation within a parent grain) is not captured in the crystal plasticity model [

14], it is not an exact faithful reproduction of the deformed microstructure. Nevertheless, previous work has demonstrated that the strain localisation predicted by such full-field crystal plasticity models is a reasonably faithful reproduction of that measured in magnesium [

14].

5. Discussion

The experimental observations in this work support those of previous studies [

8,

9,

10], namely that deformation strongly suppresses DP. In regions where DP does not occur, CP is observed. However, it is noteworthy that even after deformation, DP is not completely prevented, but is instead arrested before invading entire grains.

It is also known that deformation does not universally suppress DP in all alloy systems [

8]. In some cases, the opposite can occur, and DP can be enhanced by deformation. The precipitation model suggests that strong DP suppression is expected to arise in deformed AZ alloys due to the effect the dislocations have in facilitating nucleation of the continuously formed

precipitates. One of the reasons for the poor age hardening response of AZ alloys despite the potential to reach relatively high precipitate fractions is the difficulty in nucleating these precipitates homogeneously. Dislocations have been shown to be effective nucleation sites for the

phase, enabling much faster nucleation [

9,

10]. The acceleration of CP reduces the supersaturation available to drive DP, and in AZ magnesium alloys the model predicts this effect easily overcomes that additional driving force for DP due to the stored energy in the deformation substructure.

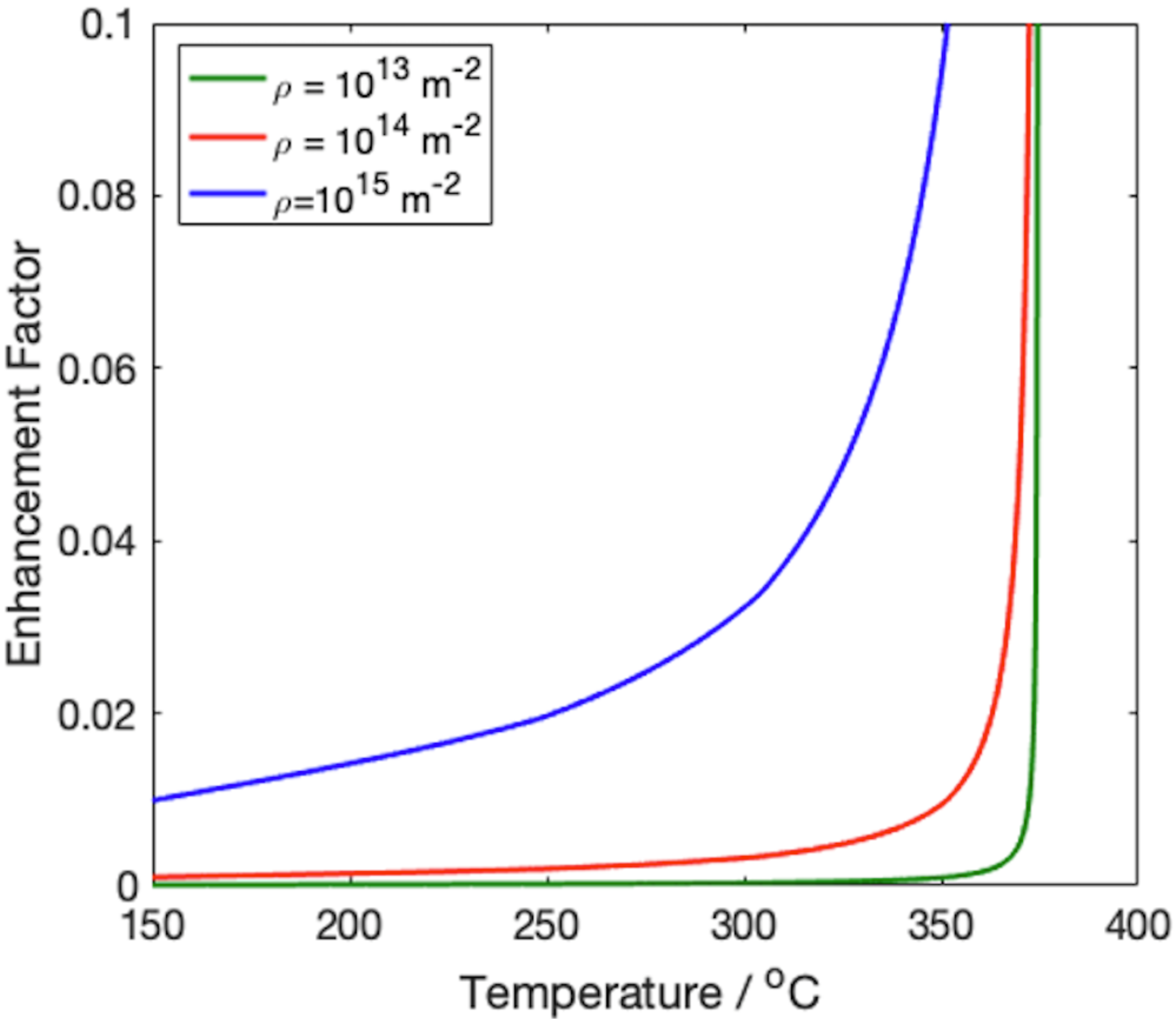

The enhancement of DP due to deformation (over the driving force due to the supersaturation) can be expressed as an

enhancement factor, defined as the ratio of the boundary pressure due to the dislocation induced stored energy (

) to the stored energy due to the supersaturation (

) (Equation (

1)). When this factor is small, the contribution of deformation to the DP boundary velocity will be small and vice versa.

Figure 10 shows the calculated enhancement factor due to deformation as a function of temperature for three dislocation density values. This is the initial value, before any CP has occurred to reduce

or recovery to reduce

. As expected, the enhancement factor will be greater when the dislocation density is greater (more stored energy in the deformation structure). However, it can also be seen that the enhancement factor at typical temperatures used for precipitation studies in AZ alloys (150–250

C) is small (<0.02), even for a very high dislocation density

m

. This demonstrates that whilst deformation will enhance the growth velocity of DP, for most practical conditions the effect is small, and is overcome by the faster CP. As temperature increases, the supersaturation decreases, so that

becomes smaller and the enhancement factor becomes greater, being asymptotic to the solvus temperature (

). However, at these high temperatures, recovery will also be very rapid so that any enhancement may not persist for long enough to influence DP growth.

A noteworthy observation in this study, which is consistent with previous work [

9], is that even after deformation, DP is not completely suppressed. To understand this, it is necessary to consider the very high level of strain heterogeneity that is typically observed in deformed magnesium, especially at lower temperature (e.g., <200

C) where non-basal slip system activation is difficult. The crystal plasticity simulations (

Figure 8) demonstrate that in the present case, strains in the regions next to the grain boundaries may exceed 4× the macroscopically applied strain. This leads to an enhanced driving force for DP in the region next to the original grain boundaries, which is exactly coincident with the region where DP starts. Therefore, locally, there can be a much higher driving force for boundary motion, leading to DP in the vicinity of the original grain boundaries before CP becomes established.

The effect of this on the pressure acting on the DP boundary can be estimated in an approximate way be considering a grain boundary region which contains a linear decrease from a high dislocation density next to the boundary (

m

) to a lower dislocation density towards the grain interior (

m

at

m from the boundary). A calculation of the pressure on the DP boundary for this situation at two temperatures is shown in

Figure 11. This calculation includes the contribution from the retarding pressure (

) due to the additional boundary area created when a hemispherical DP nodule grows out from the original grain boundary (curvature effect). The retarding pressure due to boundary curvature is given by [

15]:

where

is the high angle grain boundary energy (

Jm

[

9]) and

is the radius of the DP nodule.

It can be seen that only a very small amount of growth is needed to overcome the retarding pressure due to boundary curvature , and the enhancement to DP driving pressure (and therefore growth) will be greatest for boundaries displaced by ≃0.5 m. Therefore, small deviations in the boundary (driven by the usual DP nucleation process) will cause displacement of the boundary into a region where its growth becomes enhanced, leading to a local region of DP that is then stopped once the supersaturation ahead of the boundary is reduced significantly by CP. Therefore, although the deformation in the grain boundary regions should also enhance CP nucleation in these regions, this is overcome by the rapid DP that occurs by small displacements of the grain boundary before CP becomes established. Solute depletion in the grain boundary regions due to grain boundary precipitation may also play a role by reducing the supersaturation available for CP nucleation.

Finally, the direct role of twins in blocking DP can be considered. As demonstrated in the present study, twin boundaries and twin tips can provide impenetrable boundaries to DP growth. Twins formed within a grain therefore restrict the region into which DP can grow from a single nucleation event, as demonstrated schematically in

Figure 12a,b. However, multiple nucleation events can still lead to complete invasion of the grain (apart from in twin interiors, where DP was not observed) as shown schematically in

Figure 12c,d. In the case that the twins are very narrow compared with the grain size (as in the cold rolled material used in this study) the lack of DP within the twinned material itself has only a small effect on the DP volume fraction and can be ignored in a simple analysis. Instead, the direct effect of twin blocking on the DP fraction can be simply estimated by modifying the effective number of nuclei per grain. This is because a twin will effectively divide a single grain into two grains (ignoring the twin interior), but without introducing any new nucleation sites for DP, since twin boundaries cannot nucleate DP. In a twin free grain, one nucleus formed per grain is sufficient to produce complete invasion of the grain by DP (ignoring the competition from CP). When one twin is present, at least two nuclei per grain are required, and so on for increasing numbers of twins in each grain.

Although the details of this effect are complicated, especially in the case of intersecting twins on different planes and twins that terminate inside the grain, a very simple modification to the model was made to consider the approximate direct suppression effect due to twins by decreasing the effective nucleation rate per grain with an increasing number of twins. Turning off CP in the model, so the effect of depletion of supersaturation is ignored, the direct effect of twins on the DP volume fraction evolution predicted at 220

C is shown in

Figure 13. As expected, twins will slow the overall kinetics, but the effect is quite small compared to the very strong effect of CP in depleting the available solute (discussed previously). However, it is likely that the slowing of kinetics of DP also contributes to the additional CP that forms in the deformed case, since the two mechanisms are in competition for the untransformed volume.

Overall, the model suggests that the dominant effect of deformation is in the promotion of CP, reducing the supersaturation for DP so that it stalls early in the precipitation process. Other evidence supporting this point is that DP is suppressed after deformation even in grains which do not contain twins, as observed in the micrographs in this study and also in previous work [

8].