Substrate Composition Shapes Methanogenesis, Microbial Ecology, and Digestate Dewaterability in Microbial Electrolysis Cell-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

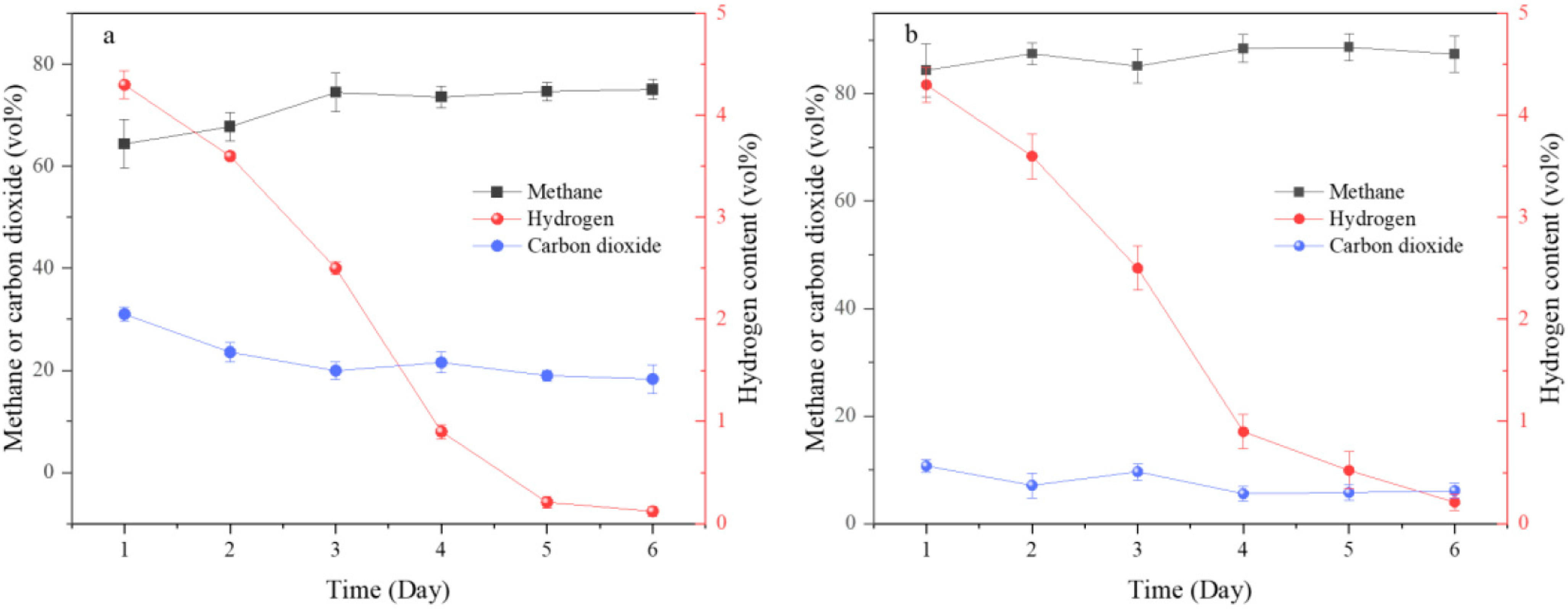

2.1. Methanogenic Performance in Different Reactors

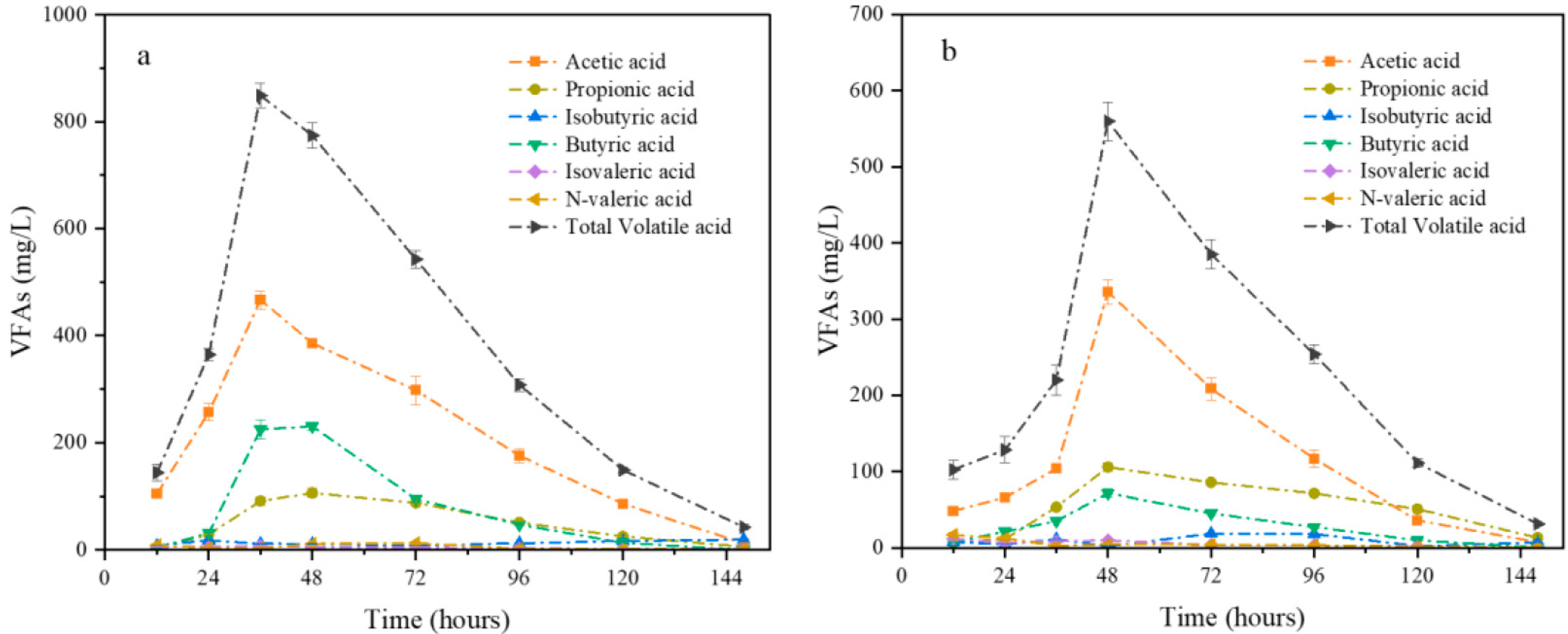

2.2. Intermediate VFAs Production and Transformation

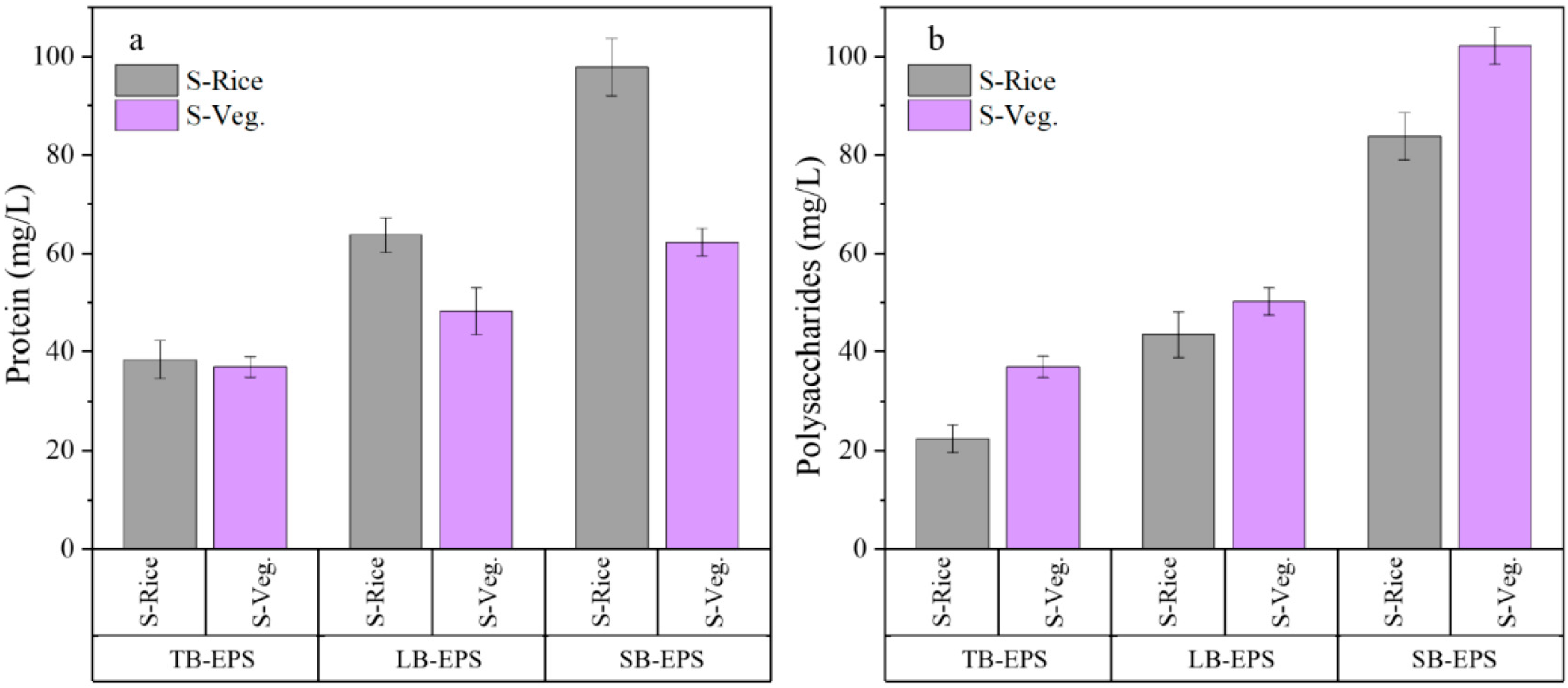

2.3. EPS Constituents in MECs Fed with Different Substrates

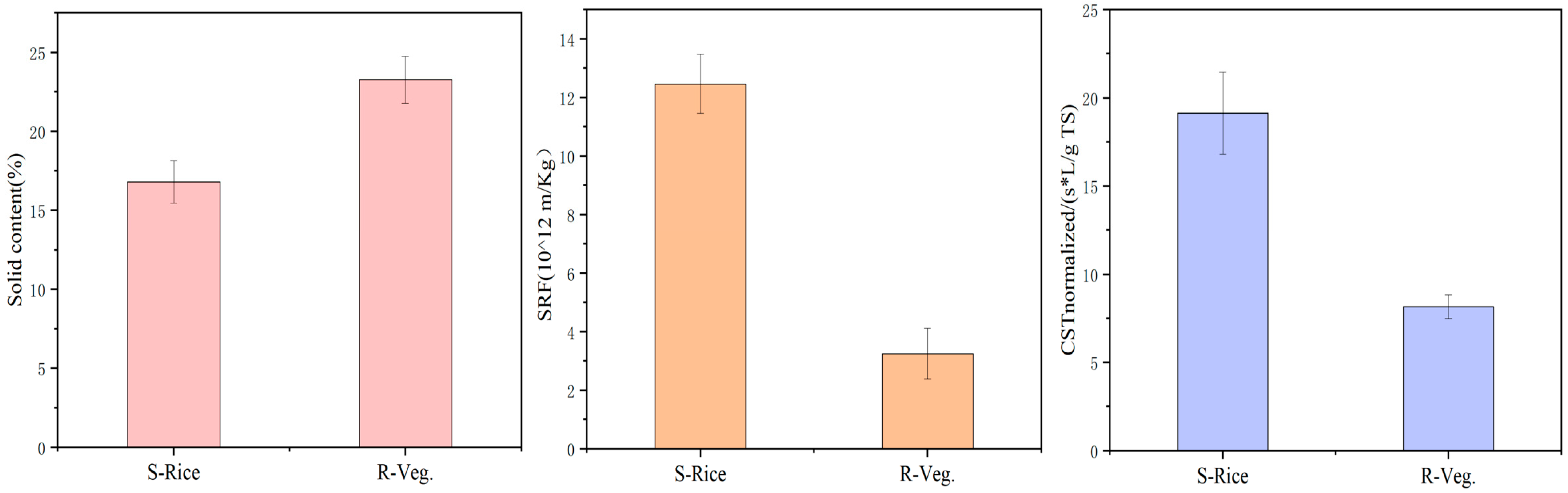

2.4. Dewatering Performance of Digestate from Reactors Fed with Different Substrates

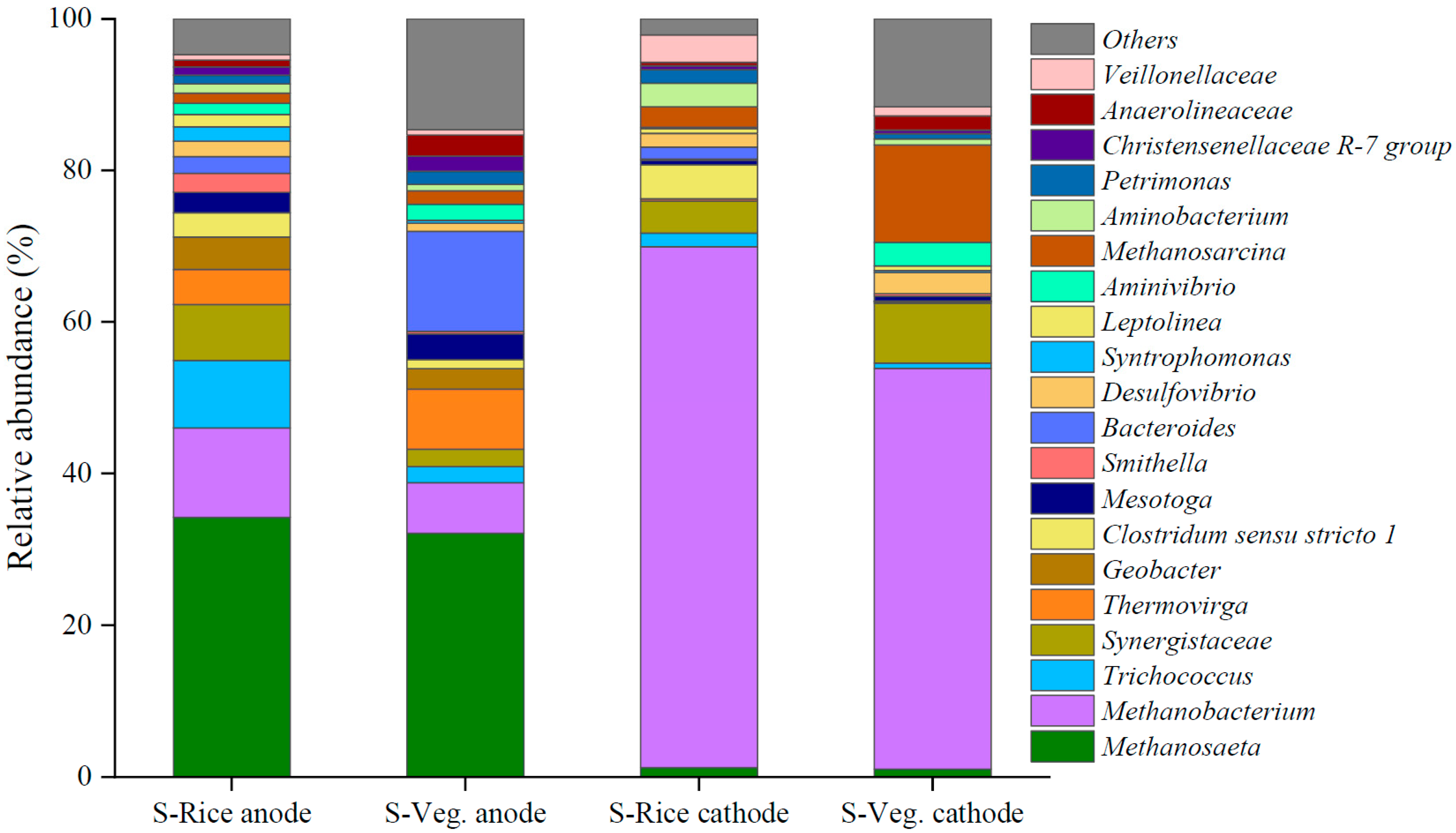

2.5. Microbial Community Constituents in Reactors Fed with Different Substrates

2.5.1. Microbial Constituents

2.5.2. Microbial Communities on the Anode

2.5.3. Microbial Communities on the Cathode

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Experimental Setup and Operation

3.3. Analytical Methods

3.3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

3.3.2. EPS Extraction

3.3.3. Methane Yield Calculation

3.3.4. Community Structure Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsui, T.-H.; Wong, J.W. A critical review: Emerging bioeconomy and waste-to-energy technologies for sustainable municipal solid waste management. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bano, A.; Singh, S.P.; Varjani, S.; Tong, Y.W. Sustainable organic waste management and future directions for environmental protection and techno-economic perspectives. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2024, 10, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Wen, Z.; Gottfried, O.; Schmidt, F.; Fei, F. A review of global strategies promoting the conversion of food waste to bioenergy via anaerobic digestion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Wright, M.M. Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 8, 2819–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Vadivelu, V.; Maspolim, Y.; Zhou, Y. In-situ alkaline enhanced two-stage anaerobic digestion system for waste cooking oil and sewage sludge co-digestion. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Meng, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Lin, C.; Yan, W. Mechanism underlying the sustained stimulatory effects of energization on biomethane recovery from food waste post-energization cessation. Environ. Res. 2024, 261, 119725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Tsuzuki, N.; Ren, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y.-Y. Enhanced biomethane production by thermophilic high-solid anaerobic co-digestion of rice straw and food waste: Cellulose degradation and microbial structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hua, J.; Cheng, J.; Yue, L.; Zhou, J. Microbial electrochemistry enhanced electron transfer in lactic acid anaerobic digestion for methane production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Leng, X.; Zhao, S.; Ji, J.; Zhou, T.; Khan, A.; Kakde, A.; Liu, P.; Li, X. A review on the applications of microbial electrolysis cells in anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 255, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo, M.; Viñas, M.; Bonmatí, A. Anaerobic digestion and electromethanogenic microbial electrolysis cell integrated system: Increased stability and recovery of ammonia and methane. Renew. Energy 2018, 120, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Bhatt, P.; Kandel, P.; Khadka, M.; Kathariya, S.; Thapa, S.; Jha, S.; Phaiju, S.; Bajracharya, S.; Yadav, A.P. Integrating microbial electrochemical cell in anaerobic digestion of vegetable wastes to enhance biogas production. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 27, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Reddy, C.N.; Min, B. In situ integration of microbial electrochemical systems into anaerobic digestion to improve methane fermentation at different substrate concentrations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 2380–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Meng, S.; Han, D.; Pan, Z.; Chen, J.; Lin, C. Optimization of in-situ synthesis of methane in microbial electrochemical systems: Influence of substrate concentration, polymerization degree, and applied voltage. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Yang, Y.; Sun, G.; Wu, D. Impact of applied voltage on methane generation and microbial activities in an anaerobic microbial electrolysis cell (MEC). Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lawati, I.M.H.D. Enhancing Biogas Generation With Conductive Material And Enzymes in Thermophilic Digestion; Sultan Qaboos University: Muscat, Oman, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Agregán, R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Kumar, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Khan, M.U.; Sarwar, A.; Sultan, M.; Rebezov, M.; Usman, M. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulose components: Challenges and novel approaches. Energies 2022, 15, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Tao, H.; Dai, X.; Dong, B.; Zhang, W. Impact of hydrophilic functional groups of macromolecular organic fractions on food waste digestate dewaterability. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, M.; Ji, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, D.; Qiao, Y. Pyrolysis behavior and product distributions of biomass six group components: Starch, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, protein and oil. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 216, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, S.; Sun, D.; Huang, H.; Chen, J.; Cen, K. Inhibition of microbial growth on air cathodes of single chamber microbial fuel cells by incorporating enrofloxacin into the catalyst layer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 72, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, D.; Wang, M.; Long, Y.; Chen, T. Enhancement of acidogenic fermentation for volatile fatty acid production from food waste: Effect of redox potential and inoculum. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Chen, H.B.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhou, Y.F.; Wang, D.B. Advances in enhanced volatile fatty acid production from anaerobic fermentation of waste activated sludge. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 694, 133741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, J.; Lin, T.; Shi, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, K.; Zhang, C.; Rui, X.; Gan, D.; Li, W. Recent Advances in Exopolysaccharide–Protein Interactions in Fermented Dairy-and Plant-Based Yogurts: Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, Health Benefits, Analytical Techniques, and Future Directions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochioka, E.; Yamashita, M.; Usui, J.; Miyake, H.; Terada, A.; Hosomi, M. Enhancing the dewaterability of anaerobically digested sludge using fibrous materials recovered from primary sludge: Demonstration from a field study. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-H.; Wu, J.; Weng, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, A. Understanding the role of cellulose fiber on the dewaterability of simulated pulp and paper mill sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittami, T.; Uematsu, K.; Nabatame, R.; Kondo, K.; Takeda, M.; Matsumoto, K. Effect of compressibility of synthetic fibers as conditioning materials on dewatering of activated sludge. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 268, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zou, C.; Lou, C.; Yang, H.; Mei, M.; Jing, H.; Cheng, S. Effects of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin on the ignition behaviors of biomass in a drop tube furnace. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 310, 123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, J.-M.; Jo, S.-W.; Yeo, H.-T.; Hong, J.W.; Yoon, H.-S. Substrate-Driven Microbial Dynamics and Digestate Traits in Microalgal Co-Digestion. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-F.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Li, Q.-S.; Yan, D.-M.; Wang, L.-L.; He, T.; Cai, Z.-X.; Zhou, H.-Z.; Song, X.-S. Anaerobic granular sludge coupled with artificial aeration or Fe-based substrate enhanced nitrogen conversion dynamic based on CW-MFCs. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 45, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Q. Impacts of biochar on anaerobic digestion of swine manure: Methanogenesis and antibiotic resistance genes dissemination. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 324, 124679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Liu, L.; Sun, D.; Ren, N.; Lee, D.-J. Isolation of Fe(III)-reducing fermentative bacterium Bacteroides sp. W7 in the anode suspension of a microbial electrolysis cell (MEC). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 3178–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Synergistic effect of extracellular polymeric substances and carbon layer on electron utilization of Fe@C during anaerobic treatment of refractory wastewater. Water Res. 2023, 231, 119609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | OTU | Chao | Coverage | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-Rice anode | 201 | 275 | 0.99036 | 2.96 | 0.1533 |

| S-Rice cathode | 115 | 149 | 0.99439 | 1.89 | 0.2888 |

| K-Veg. anode | 264 | 349 | 0.98733 | 3.06 | 0.1586 |

| K-Veg. cathode | 142 | 185 | 0.99338 | 2.51 | 0.1726 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Cui, B.; Xin, X.; Iradukunda, Y.; Yan, W. Substrate Composition Shapes Methanogenesis, Microbial Ecology, and Digestate Dewaterability in Microbial Electrolysis Cell-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. Methane 2026, 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/methane5010002

Yang J, Cui B, Xin X, Iradukunda Y, Yan W. Substrate Composition Shapes Methanogenesis, Microbial Ecology, and Digestate Dewaterability in Microbial Electrolysis Cell-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. Methane. 2026; 5(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/methane5010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jiaojiao, Baihui Cui, Xiaodong Xin, Yves Iradukunda, and Wangwang Yan. 2026. "Substrate Composition Shapes Methanogenesis, Microbial Ecology, and Digestate Dewaterability in Microbial Electrolysis Cell-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste" Methane 5, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/methane5010002

APA StyleYang, J., Cui, B., Xin, X., Iradukunda, Y., & Yan, W. (2026). Substrate Composition Shapes Methanogenesis, Microbial Ecology, and Digestate Dewaterability in Microbial Electrolysis Cell-Assisted Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. Methane, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/methane5010002