An Efficient Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Enhanced Wind Energy Capture

Abstract

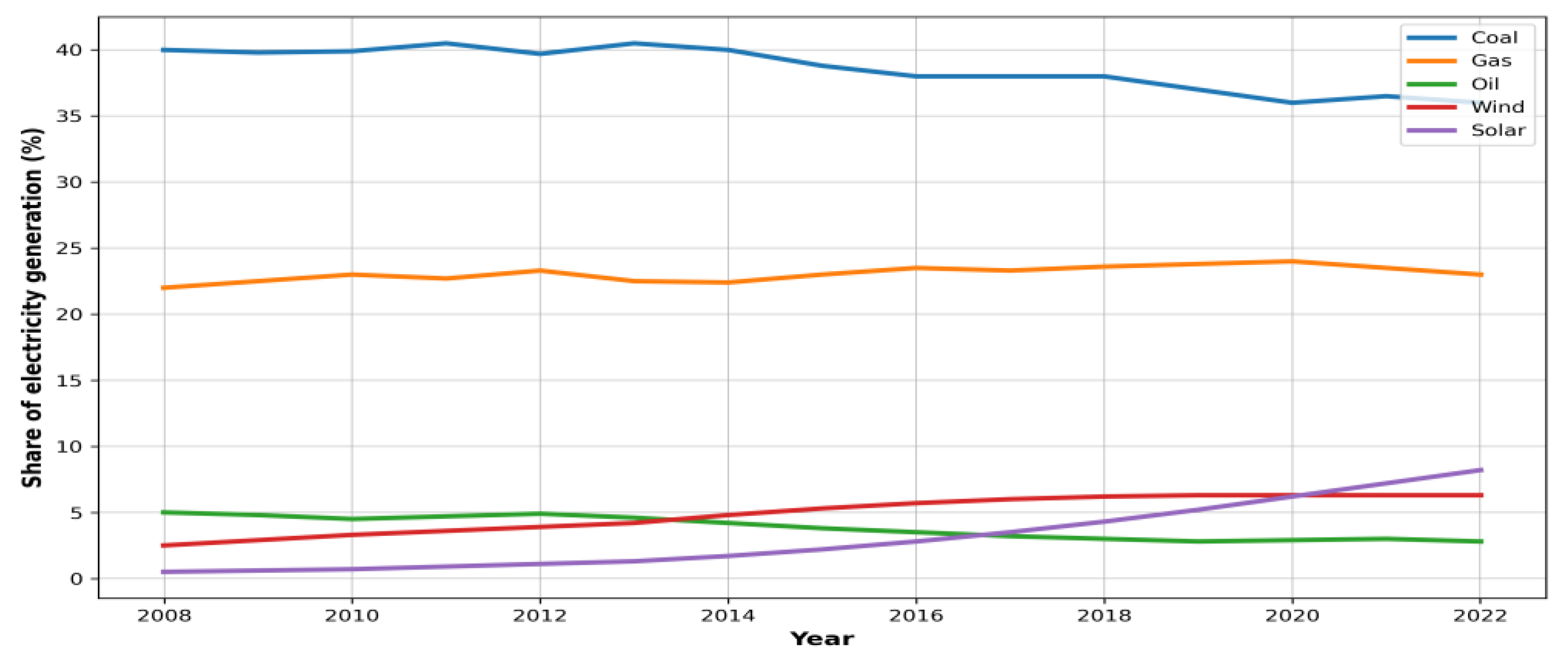

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

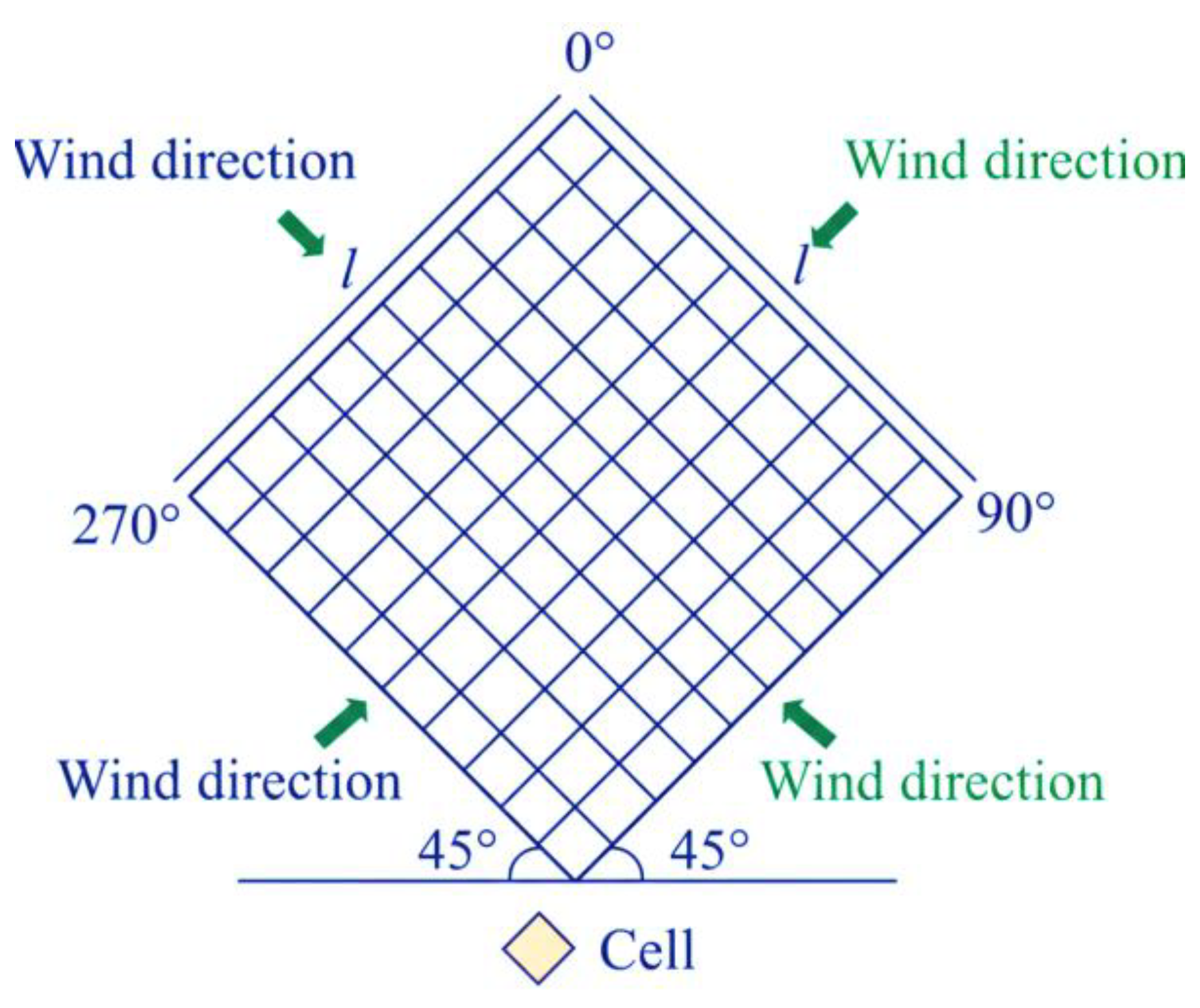

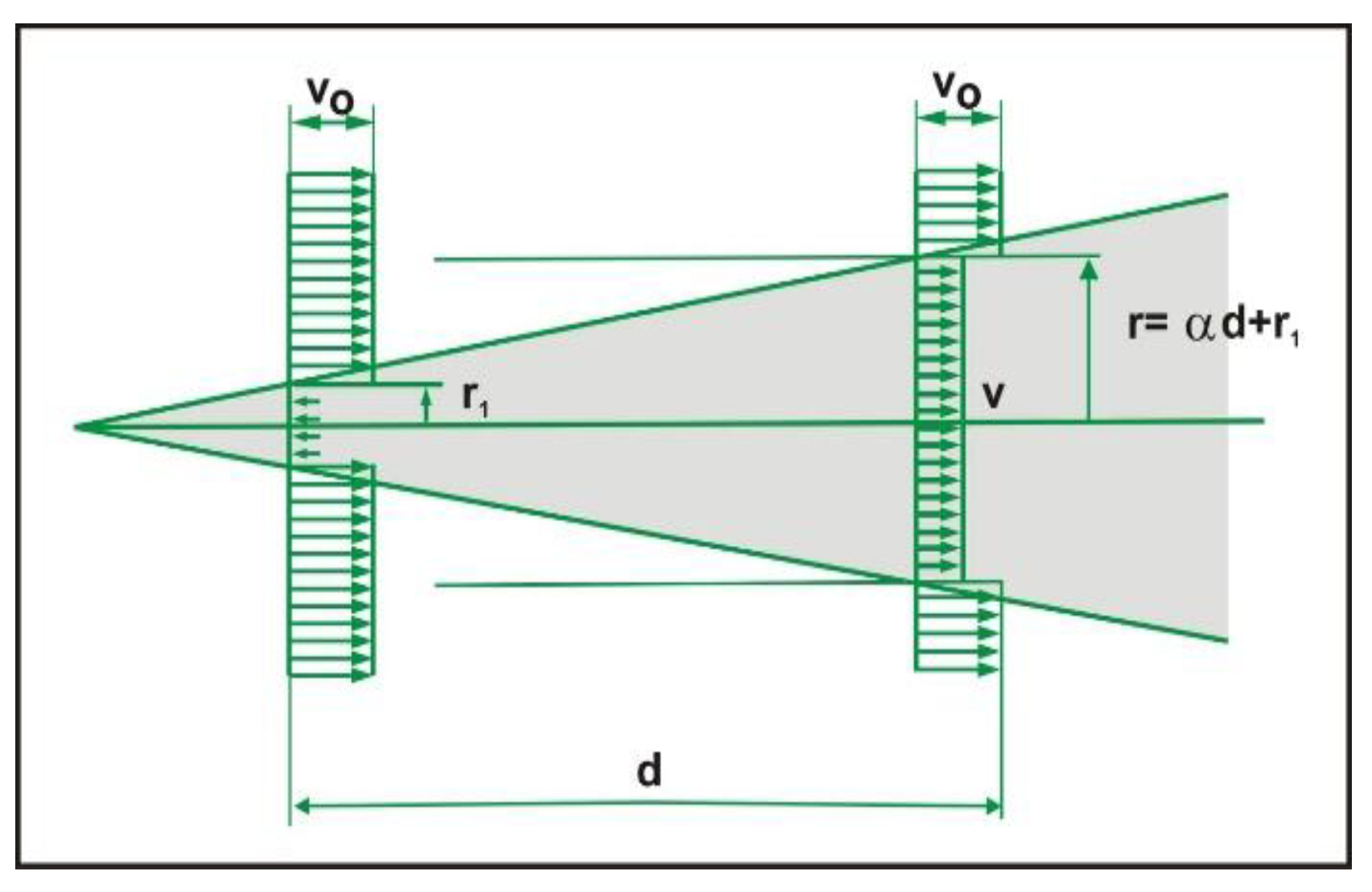

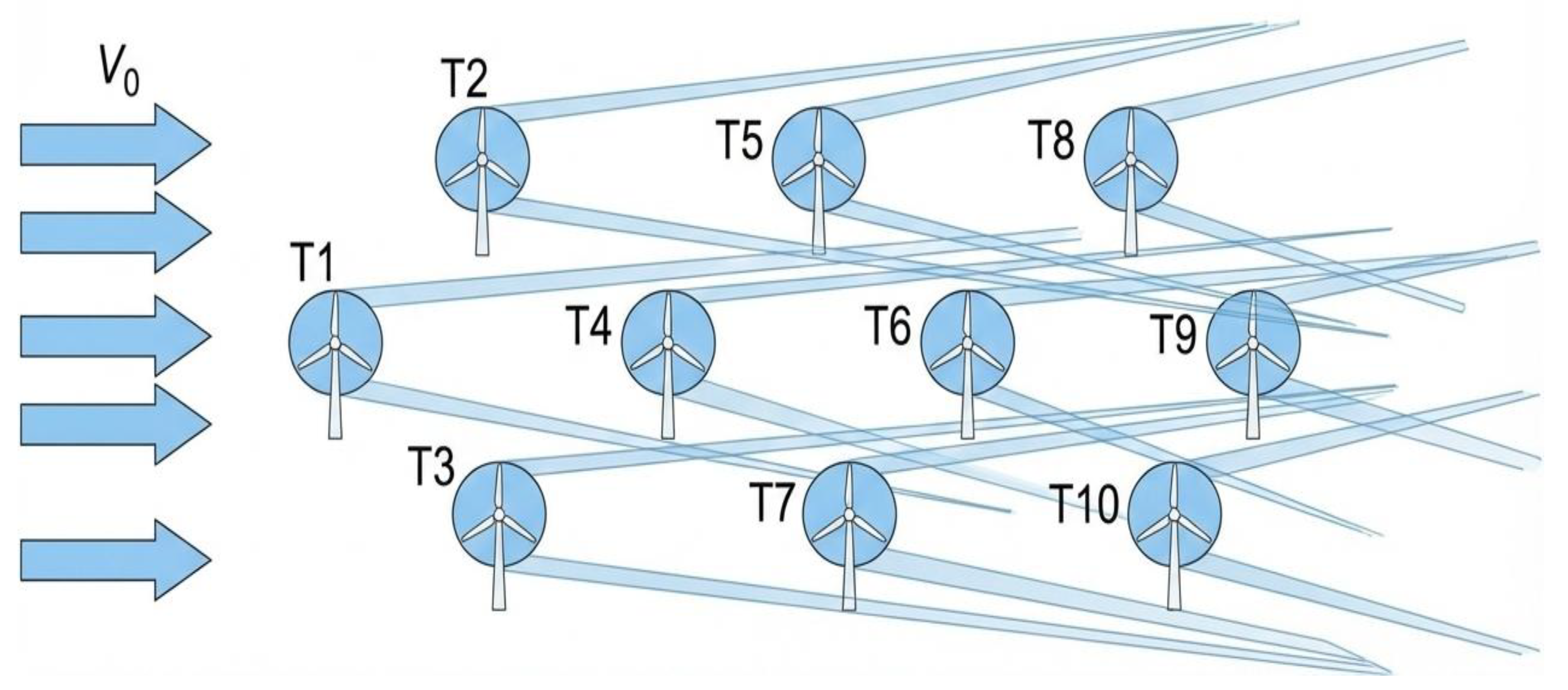

3.1. Wake Model

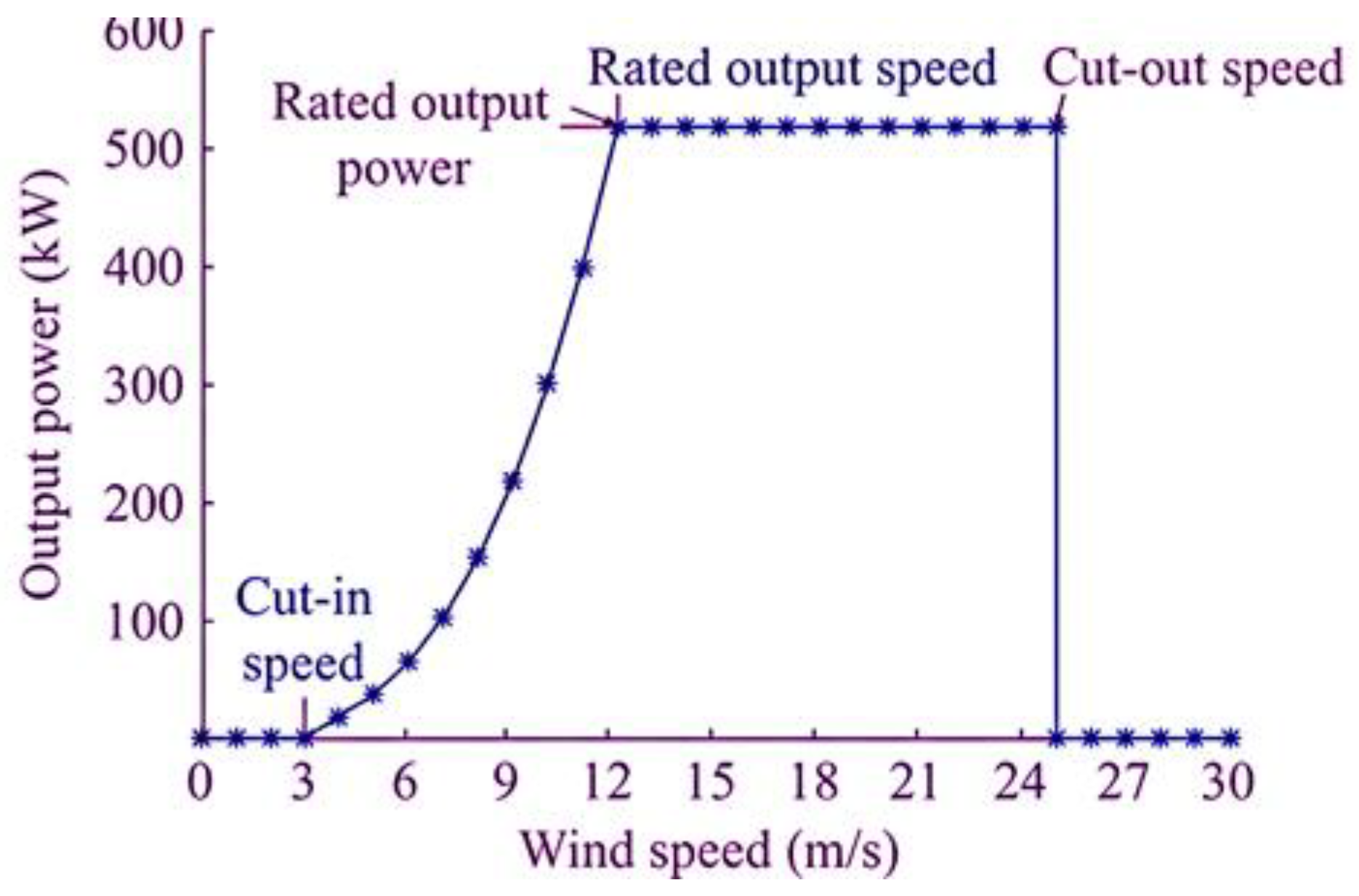

3.2. Power Model

3.3. Cost Model

3.4. Objective Function

3.5. Constraints Modeling

3.6. Energy Efficiency Index (EEI)

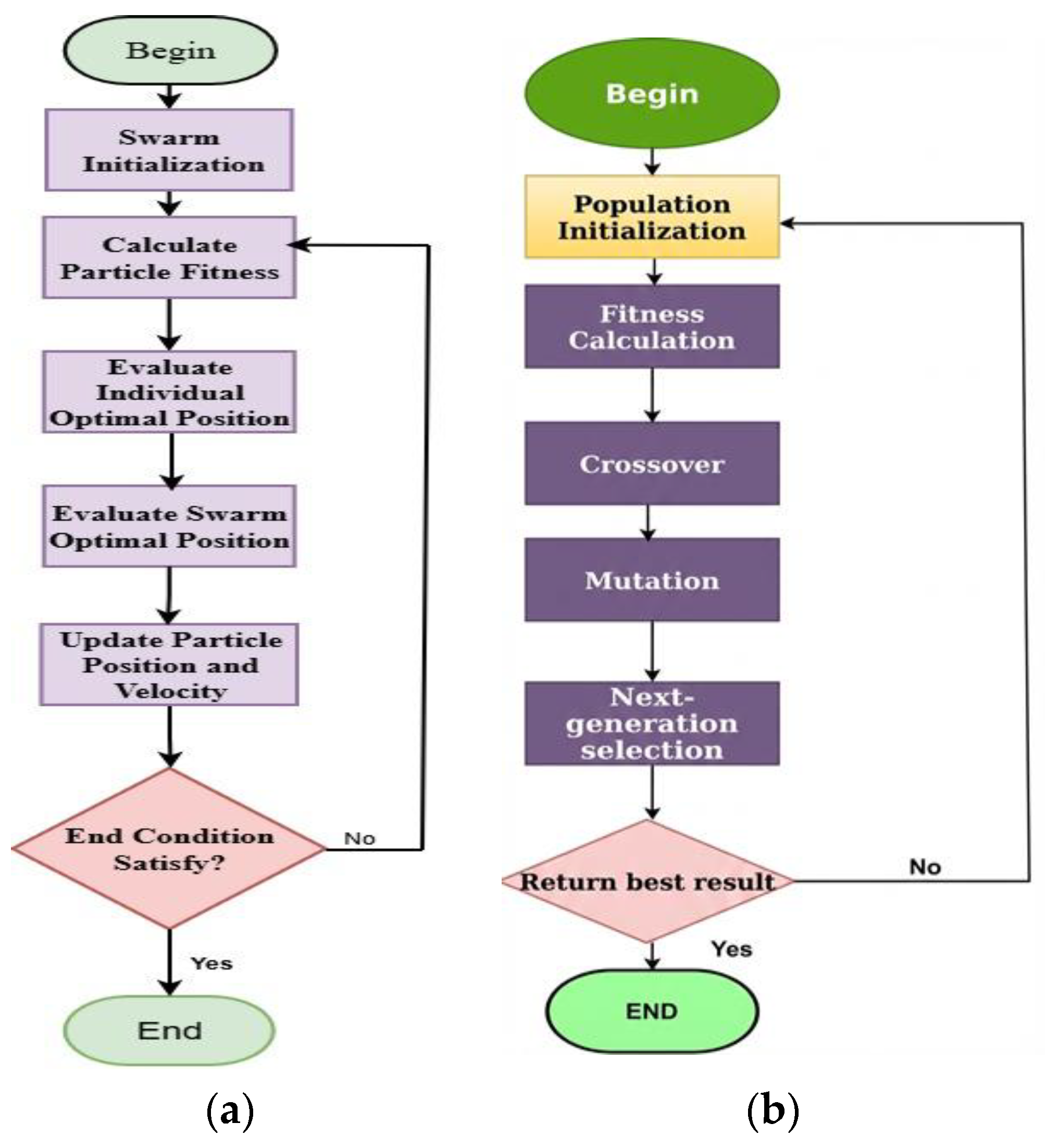

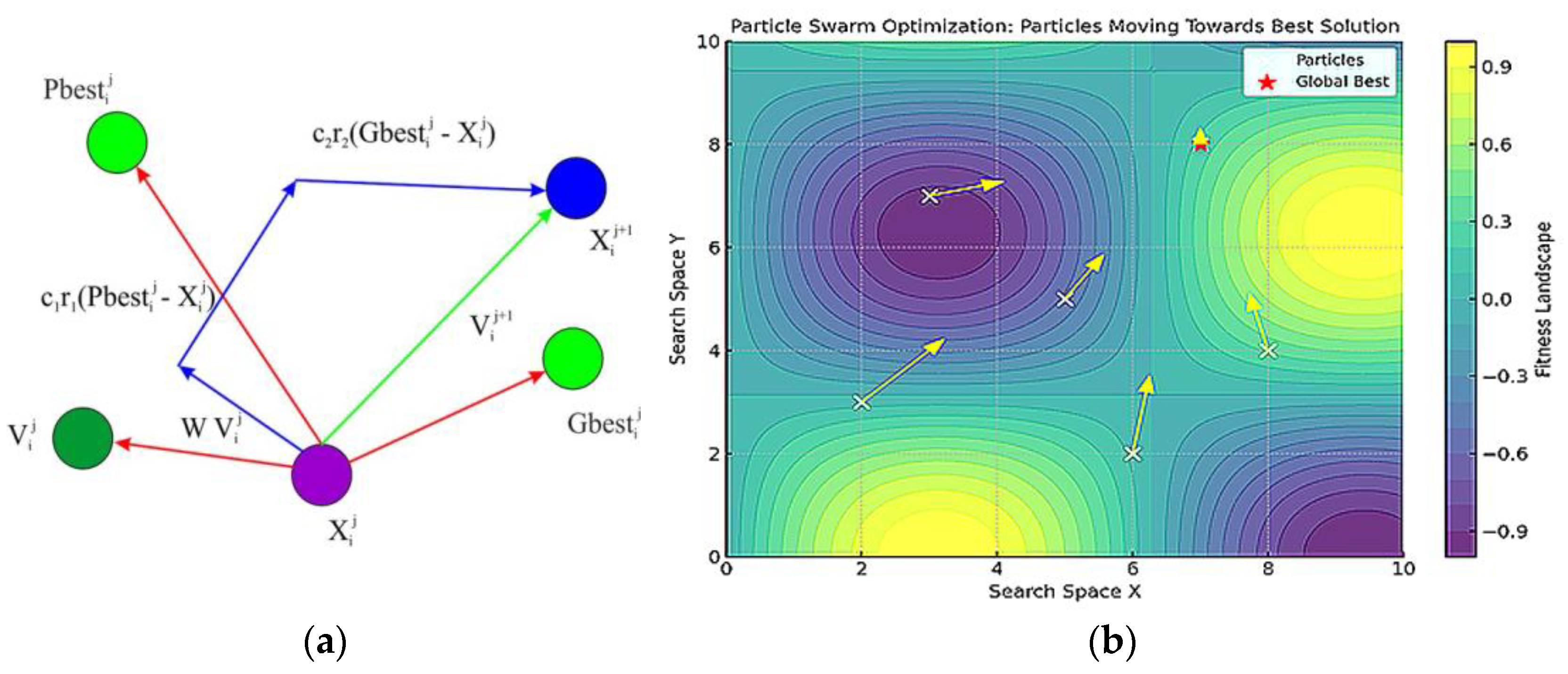

3.7. Particle Swarm Improvement Process (PSO) Algorithm

3.8. Genetic Algorithm (GA)

3.9. Proposed (PSO-GA) Algorithm

4. Results

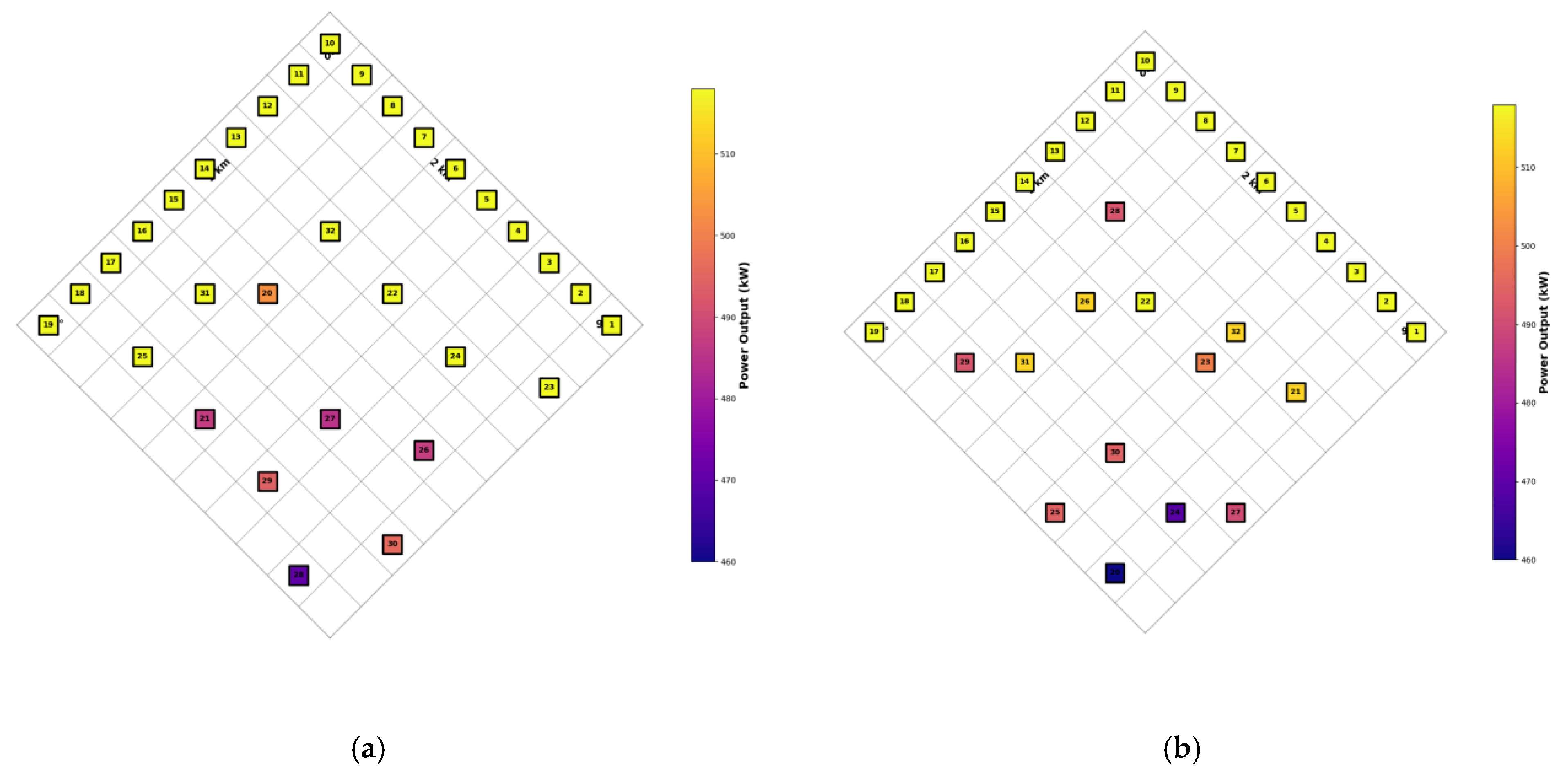

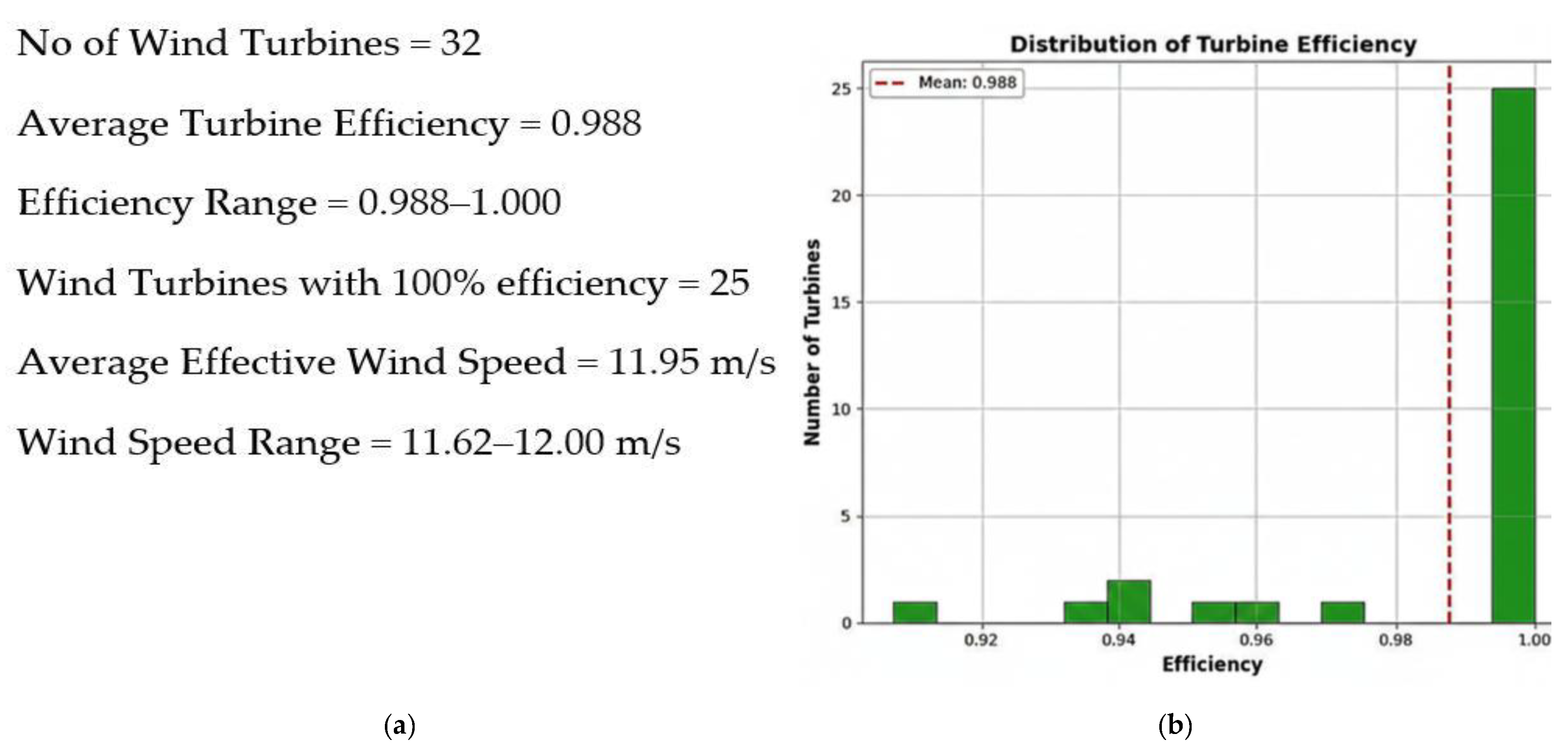

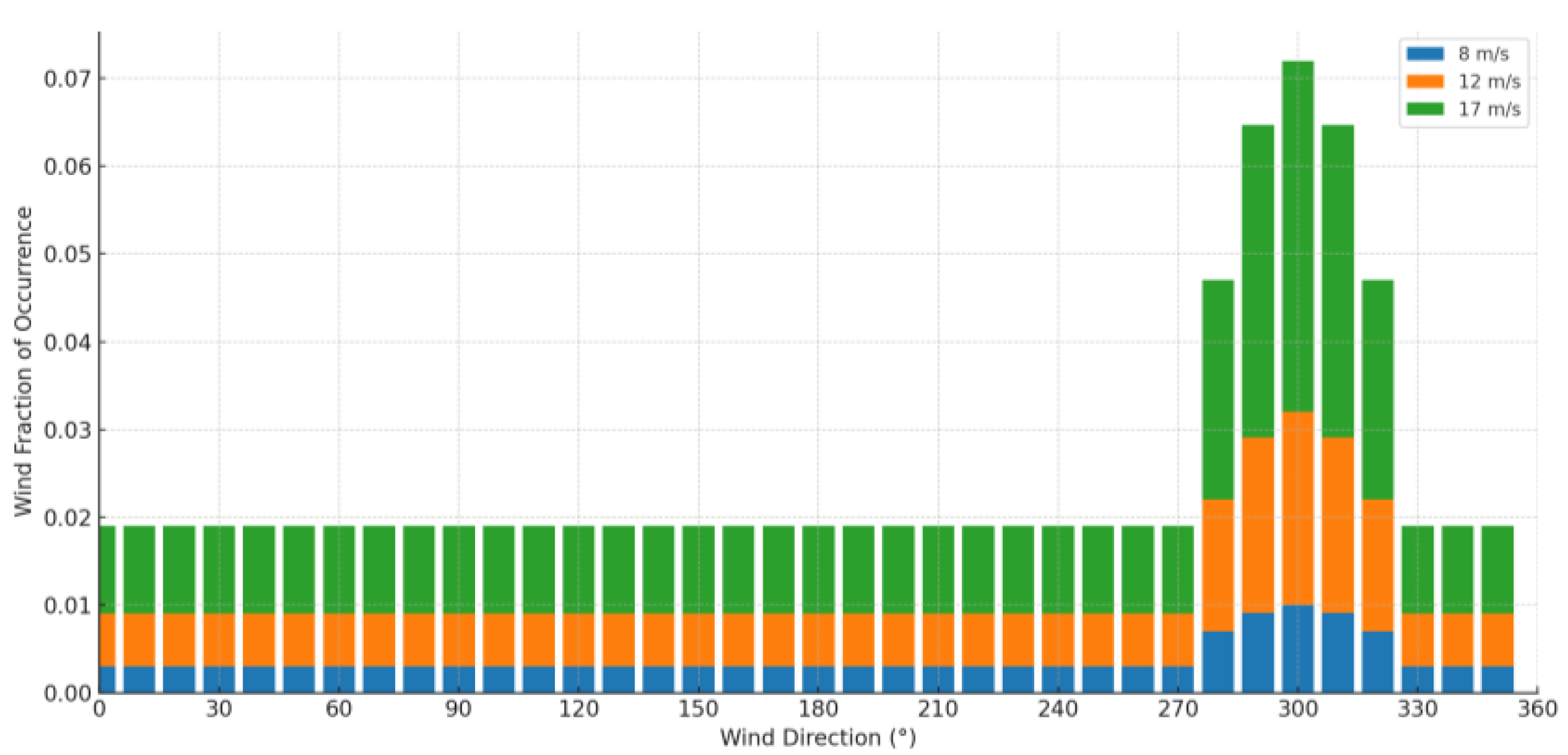

4.1. Case 1

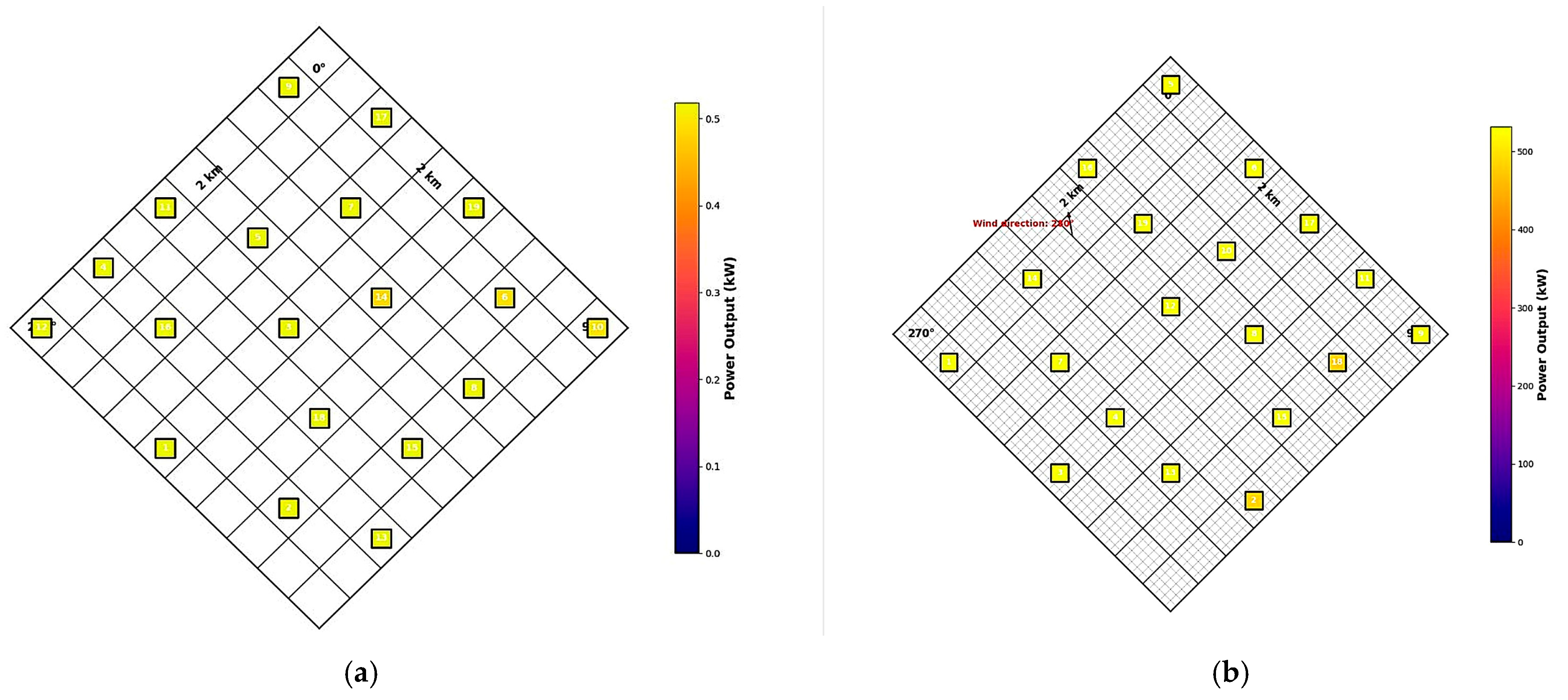

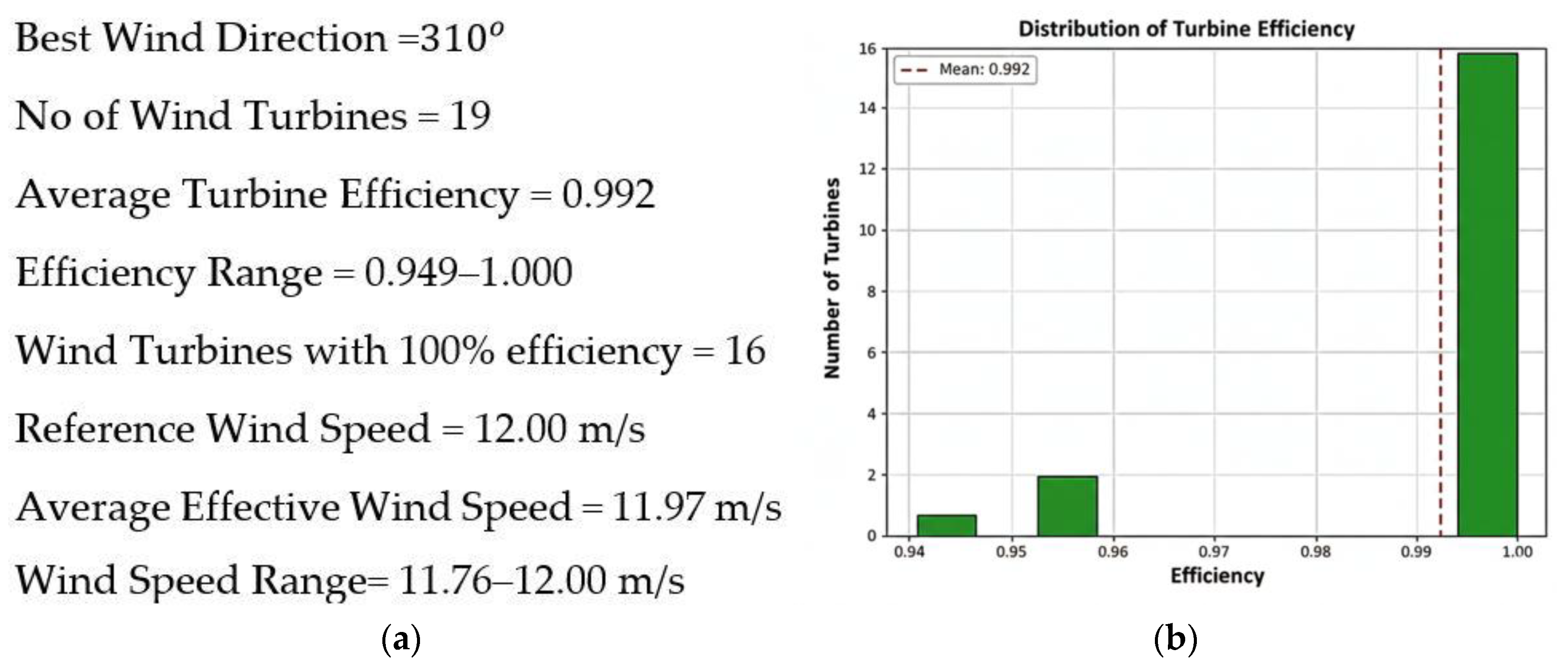

4.2. Case 2

4.3. Case 3

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| EEI | Energy Efficiency Index |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GWEC | Global Wind Energy Council |

| MHMs | Metaheuristic Methods |

| MOP | Multi-Objective Improvement Process |

| NFL | No Free Lunch |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| WF | Wind Farm |

| WFL | Wind Farm Layout |

| WFLO | Wind Farm Layout Optimization |

| WFL-DO | Wind Farm Discrete Optimization |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| ρ | Air Density |

| α | Axial Induction Factor |

| Pi | |

| Efficiency | |

| Cp | Power Coefficient |

| Thrust Coefficient | |

| Inertia Weight | |

| Particle Best Position | |

| Global Best Position |

References

- Yu, X.; Zhang, W. A teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm with reinforcement learning to address wind farm layout optimization problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 151, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhuo, F. Modeling and stability issues of voltage-source converter-dominated power systems: A review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 8, 1530–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Dong, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Duić, N.; Joo, Y.H.; Song, D. Wind turbine wakes modeling and applications: Past, present, and future. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roga, S.; Bardhan, S.; Kumar, Y.; Dubey, S.K. Recent technology and challenges of wind energy generation: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102239. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, P.; Hu, W.; Soltani, M.; Chen, Z. Optimized placement of wind turbines in large-scale offshore wind farm using particle swarm optimization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2015, 6, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, A.M.; El-Shorbagy, M.A. Optimization of wind turbines siting in a wind farm using genetic algorithm based local search. Renew. Energy 2018, 123, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, S.; Barthelmie, R.; Pryor, S.; Rathmann, O.; Larsen, S.; Højstrup, J.; Thøgersen, M. Analytical modelling of wind speed deficit in large offshore wind farms. Wind Energy 2006, 9, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmie, R.J.; Rathmann, O.; Frandsen, S.T.; Hansen, K.S.; Politis, E.; Prospathopoulos, J.; Rados, K.; Cabezón, D.; Schlez, W.; Phillips, J.; et al. Modelling and measurements of wakes in large wind farms. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007, 75, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, P.; Mitra, K. Determining layout of a wind farm with optimal number of turbines: A decomposition based approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişbot, S.; Turgut, Ö.; Tunç, M.; Çamdalı, Ü. Optimal positioning of wind turbines on Gökçeada using multi-objective genetic algorithm. Wind Energy Int. J. Prog. Appl. Wind Power Convers. Technol. 2010, 13, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Z. A two-echelon wind farm layout planning model. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2015, 6, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastankhah, M.; Porté-Agel, F. A new analytical model for wind-turbine wakes. Renew. Energy 2014, 70, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Hu, J.; Law, S.-S. Optimization of wind farm layout with modified genetic algorithm based on boolean code. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 181, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, L. Optimization of wind turbine layout position in a wind farm using a newly-developed two-dimensional wake model. Appl. Energy 2016, 174, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Gao, X.; Yang, H. A review of full-scale wind-field measurements of the wind-turbine wake effect and a measurement of the wake-interaction effect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, B.; Mínguez, R.; Guanche, R. Offshore wind farm layout optimization using mathematical programming techniques. Renew. Energy 2013, 53, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Porté-Agel, F. Simulation of turbulent flow inside and above wind farms: Model validation and layout effects. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2013, 146, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosetti, G.; Poloni, C.; Diviacco, B. Optimization of wind turbine positioning in large windfarms by means of a genetic algorithm. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1994, 51, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, S.A.; Hussaini, M.Y.; Abdullah, M.M. Placement of wind turbines using genetic algorithms. Renew. Energy 2005, 30, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmidis, G.; Lazarou, S.; Pyrgioti, E. Optimal placement of wind turbines in a wind park using Monte Carlo simulation. Renew. Energy 2008, 33, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, P.; Winstead, V.; Steevens, P. Optimal placement of wind turbines: A Monte Carlo approach with large historical data set. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology, Normal, IL, USA, 20–22 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Masoudi, S.M.; Baneshi, M. Layout optimization of a wind farm considering grids of various resolutions, wake effect, and realistic wind speed and wind direction data: A techno-economic assessment. Energy 2022, 244, 123188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, S.; Doekemeijer, B.; Vali, M.; Meyers, J.; van Wingerden, J.W. A control-oriented dynamic wind farm model: WFSim. Wind Energy Sci. 2018, 3, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Qiu, C.; Lu, L.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, H. Wind turbine power modelling and optimization using artificial neural network with wind field experimental data. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Y.; Yang, Q.; Stoevesandt, B.; Sun, Y. Optimization of wind farm layout with optimum coordination of turbine cooperations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 164, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, R.; Hassan, M.Y.; Raheem, A.; Rasheed, N. Wind farm layout optimization using area dimensions and definite point selection techniques. Renew. Energy 2016, 88, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.P.J.; Ning, A.; Dykes, K. Optimization of turbine design in wind farms with multiple hub heights, using exact analytic gradients and structural constraints. Wind Energy 2019, 22, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.P.; Ning, A. Coupled wind turbine design and layout optimization with nonhomogeneous wind turbines. Wind Energy Sci. 2019, 4, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchekara, H.R.; Sha’aban, Y.A.; Shahriar, M.S.; Ramli, M.A.; Mas’ud, A.A. Wind Farm Layout Optimization/Expansion with Real Wind Turbines Using a Multi-Objective EA Based on an Enhanced Inverted Generational Distance Metric Combined with the Two-Archive Algorithm 2. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.A.; Bouchekara, H.R. Wind Farm Layout Optimization Considering Obstacles Using a Binary Most Valuable Player Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 131553–131564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Zhang, J.; Messac, A.; Castillo, L. Optimizing the arrangement and the selection of turbines for wind farms subject to varying wind conditions. Renew. Energy 2013, 52, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Ge, M.; Gao, X.; Du, B.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y. Wind farm layout optimization to minimize the wake induced turbulence effect on wind turbines. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamati, E.; Kariman, H.; Hoseinzadeh, S. Experimental and computational fluid dynamic study of water flow and submerged depth effects on a tidal turbine performance. Water 2023, 15, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, R.; Hassan, M.Y.; Raheem, A.; Wu, Y.K. Wake effect modeling: A review of wind farm layout optimization using Jensen’s model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, O.C.; Andrade, V.R.; Rivas, J.J.R.; González, R.O. Comparison of power coefficients in wind turbines considering the tip speed ratio and blade pitch angle. Energies 2023, 16, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.P.; Suganthan, P.N.; Amaratunga, G.A. Optimal placement of wind turbines in a windfarm using L-SHADE algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Tan, D.; Liu, L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: An overview. Soft Comput. 2017, 22, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Cho, K. Simulated annealing algorithm for wind farm layout optimization: A benchmark study. Energies 2019, 12, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization In Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shorbagy, M.A.; El-Refaey, A.M. A hybrid genetic-firefly algorithm for engineering design problems. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2022, 9, 706–730. [Google Scholar]

- Haldurai, L.; Madhubala, T.; Rajalakshmi, R. A study on genetic algorithm and its applications. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Asaah, P.; Hao, L.; Ji, J. Optimal Placement of Wind Turbines in Wind Farm Layout Using Particle Swarm Optimization. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2021, 9, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Nt | Power Extracted | Wake Loss | AEP (MWh) | Efficiency % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | 32 | 16,389.73 | 199.06 | 143,574,034.8 | 98.8 |

| [43] | 32 | 16,326.59 | 262.2 | 143,020,928.4 | 98.42 |

| Strategy | Nt | Power Extracted | Wake Loss | AEP (MWh) | Efficiency % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | 19 | 9770.8032 | 78.7968 | 85,592.2 | 99.2 |

| [43] | 19 | 9741.3 | 108.3 | 85,333.79 | 98.9 |

| Strategy | Nt | Power Extracted | Wake Loss | AEP (MWh) | Efficiency % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | 15 | 7713.79 | 62.21 | 67,572.8 | 99.2 |

| [43] | 15 | 7690.46 | 85.54 | 67,368.4 | 98.9 |

| Case # | EEI by Proposed Strategy | EEI [43] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 4048.26 | 4016.34 | 0.0066 |

| Case 2 | 2423.2 | 2406.1 | |

| Case 3 | 1913.01 | 1899.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rashid, M.; Raheem, A.; Shakoor, R.; Masud, M.I.; Arfeen, Z.A.; Jumani, T.A. An Efficient Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Enhanced Wind Energy Capture. Wind 2026, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010005

Rashid M, Raheem A, Shakoor R, Masud MI, Arfeen ZA, Jumani TA. An Efficient Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Enhanced Wind Energy Capture. Wind. 2026; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleRashid, Muhammad, Abdur Raheem, Rabia Shakoor, Muhammad I. Masud, Zeeshan Ahmad Arfeen, and Touqeer Ahmed Jumani. 2026. "An Efficient Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Enhanced Wind Energy Capture" Wind 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010005

APA StyleRashid, M., Raheem, A., Shakoor, R., Masud, M. I., Arfeen, Z. A., & Jumani, T. A. (2026). An Efficient Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Enhanced Wind Energy Capture. Wind, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010005