Exploratory Analysis of Wind Resource and Doppler LiDAR Performance in Southern Patagonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Field Deployment of Doppler LiDAR

2.1. Doppler LiDAR Principles for Wind Profiling

2.2. Acquisition and Institutional Integration

2.3. System Deployment and Power Supply Configuration

- Autonomous operation with minimal field intervention

- Redundant communication options (GSM/GPRS, Ethernet, Iridium/BGAN satellite)

- Operational temperature range of −40 °C to +50 °C

- IP67-rated sealed connectors for harsh environments

- Integrated meteorological station measuring pressure, temperature, and humidity for data correction

- Dual power supply compatibility (AC/DC) with high-efficiency DC/DC converters

3. Data Analysis

3.1. Software Tools for Data Processing

3.2. Data Structure, Conversion and Visualization

3.3. Statistical Modeling of Wind Speed Distributions

3.3.1. Parametric and Non-Parametric Modeling of Wind Speed Distributions

3.3.2. Application to the Patagonian LiDAR Dataset

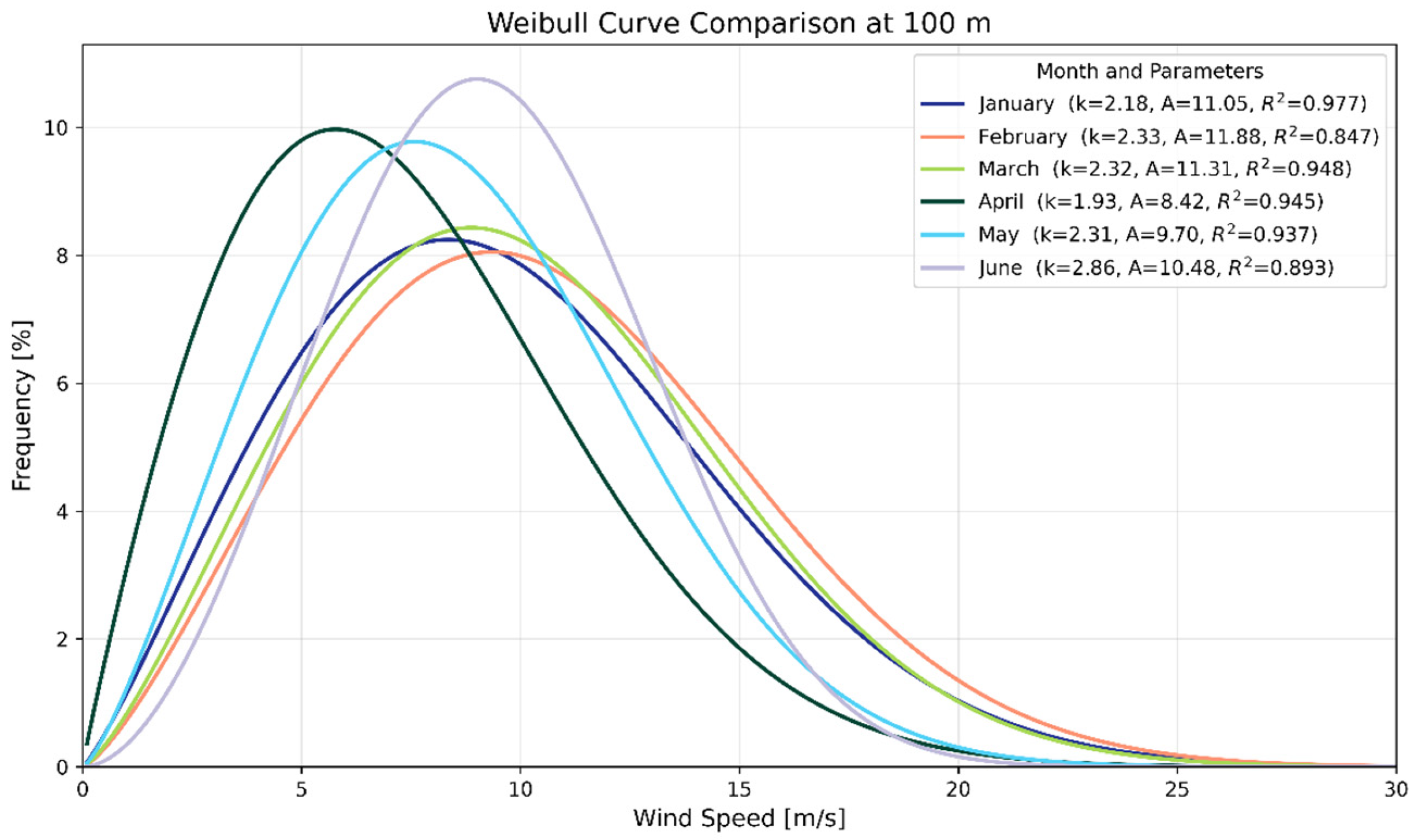

- Weibull parameters (A, k) were obtained using Windographer, following the MLE methodology described in Section 3.3.1. These parameters form the primary basis for the subsequent AEP estimation.

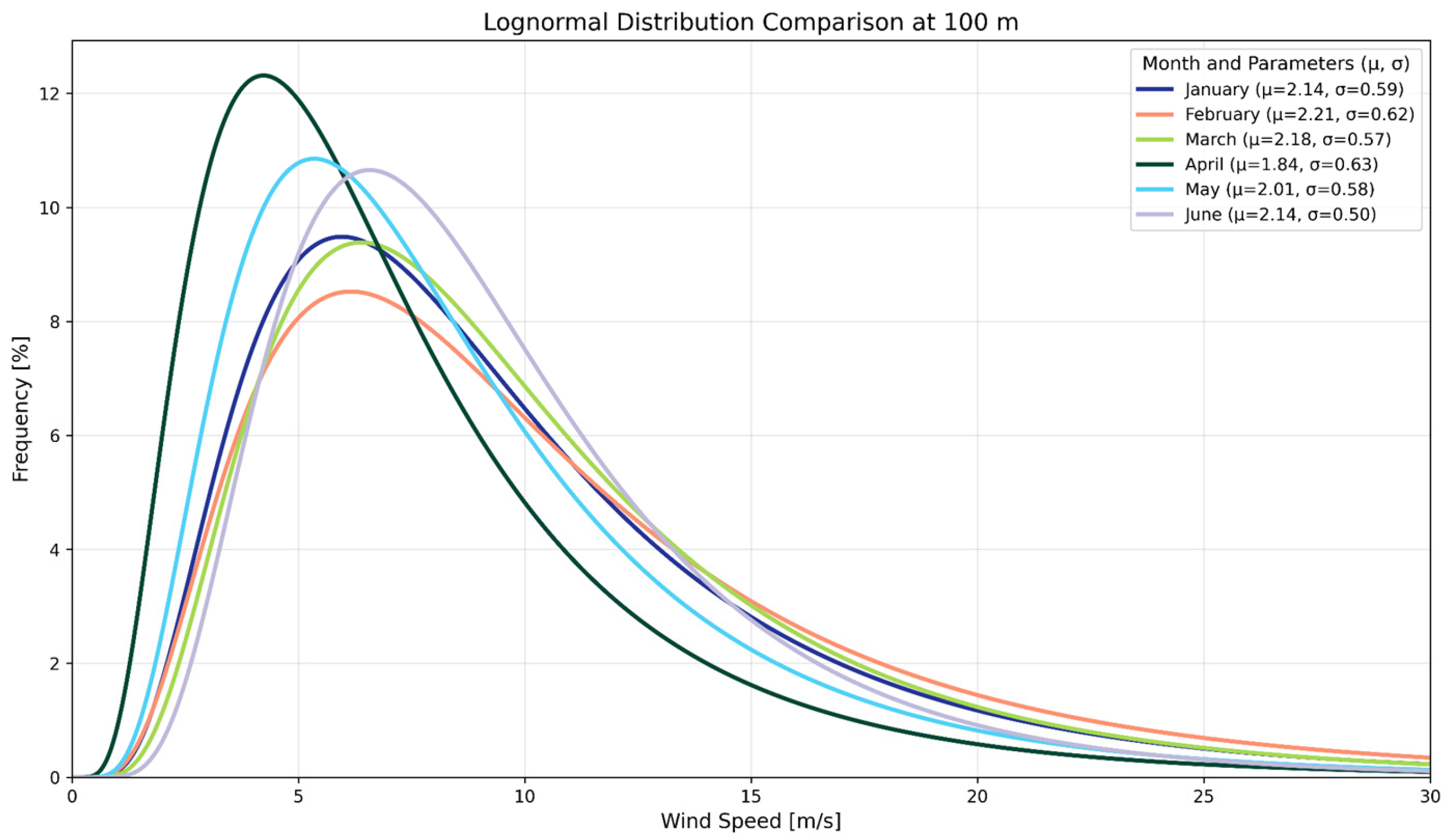

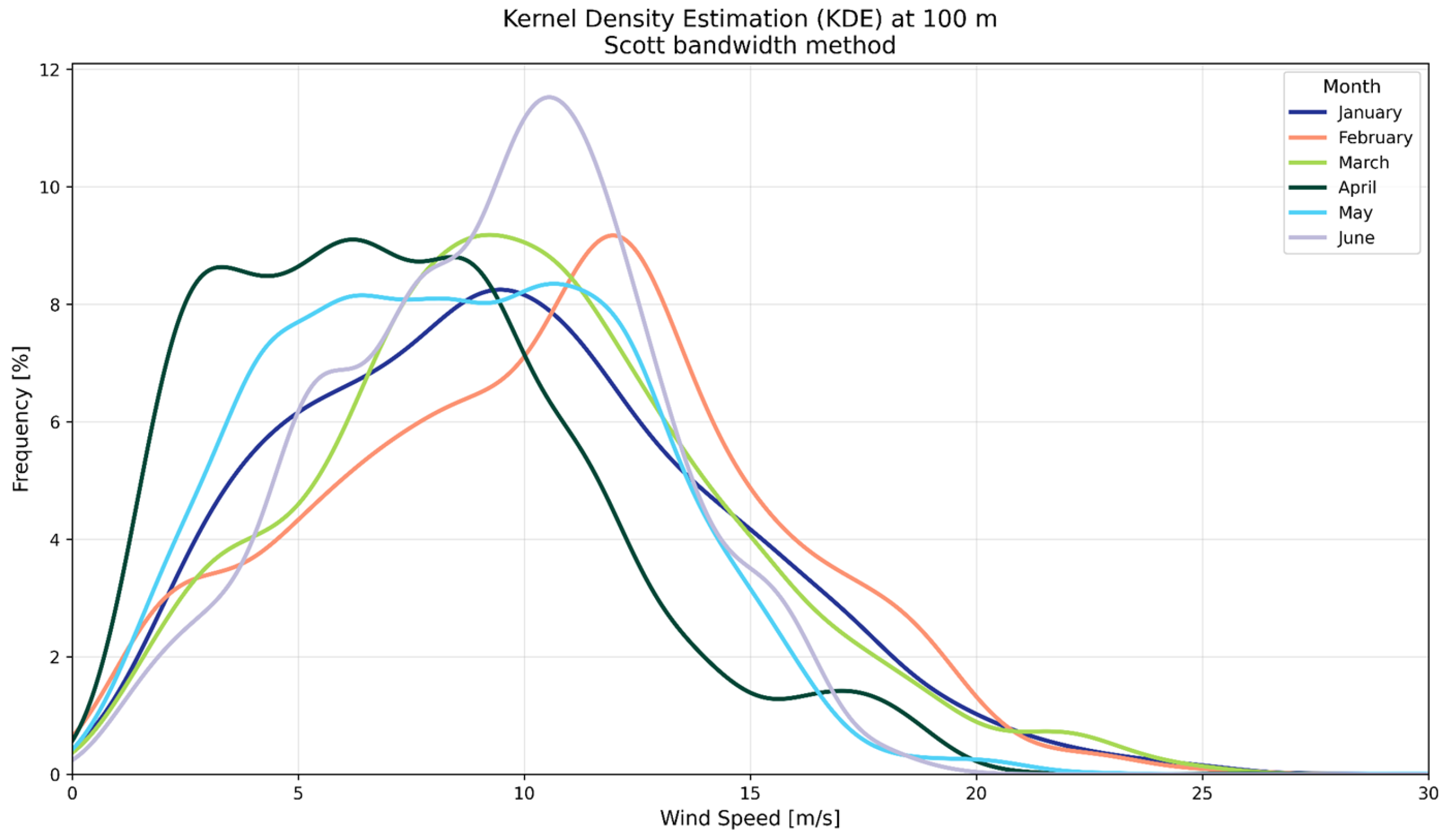

- Lognormal parameters (μ, σ of ln V) and non-parametric Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) were computed in Python using the SciPy library. KDE was implemented with a Gaussian kernel, with bandwidth automatically selected according to Scott’s rule, thereby avoiding user-dependent tuning and ensuring objective smoothing.

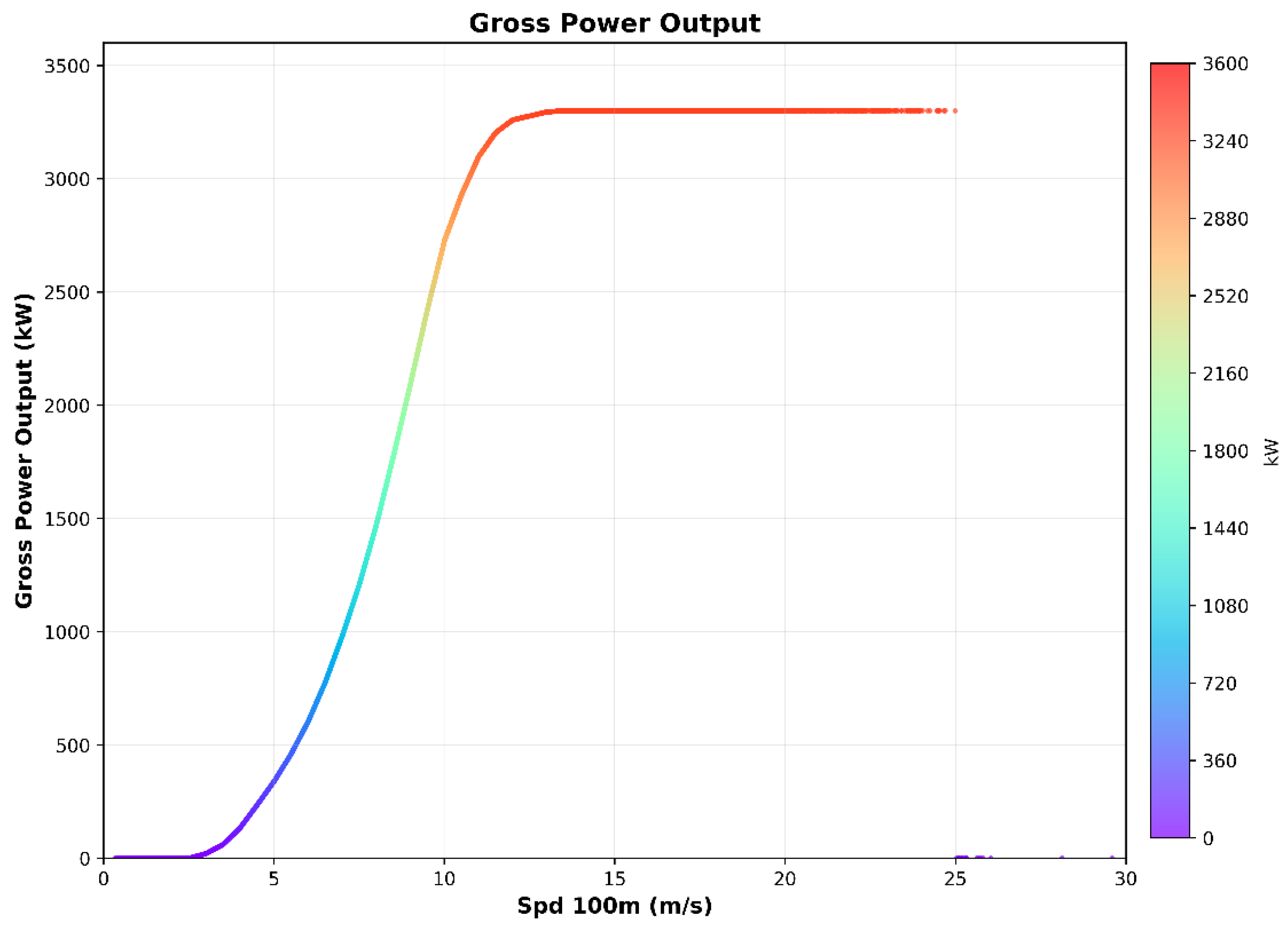

3.3.3. From Power Curve to Annual Energy Production (AEP)

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Diurnal Wind Profile and LiDAR Performance

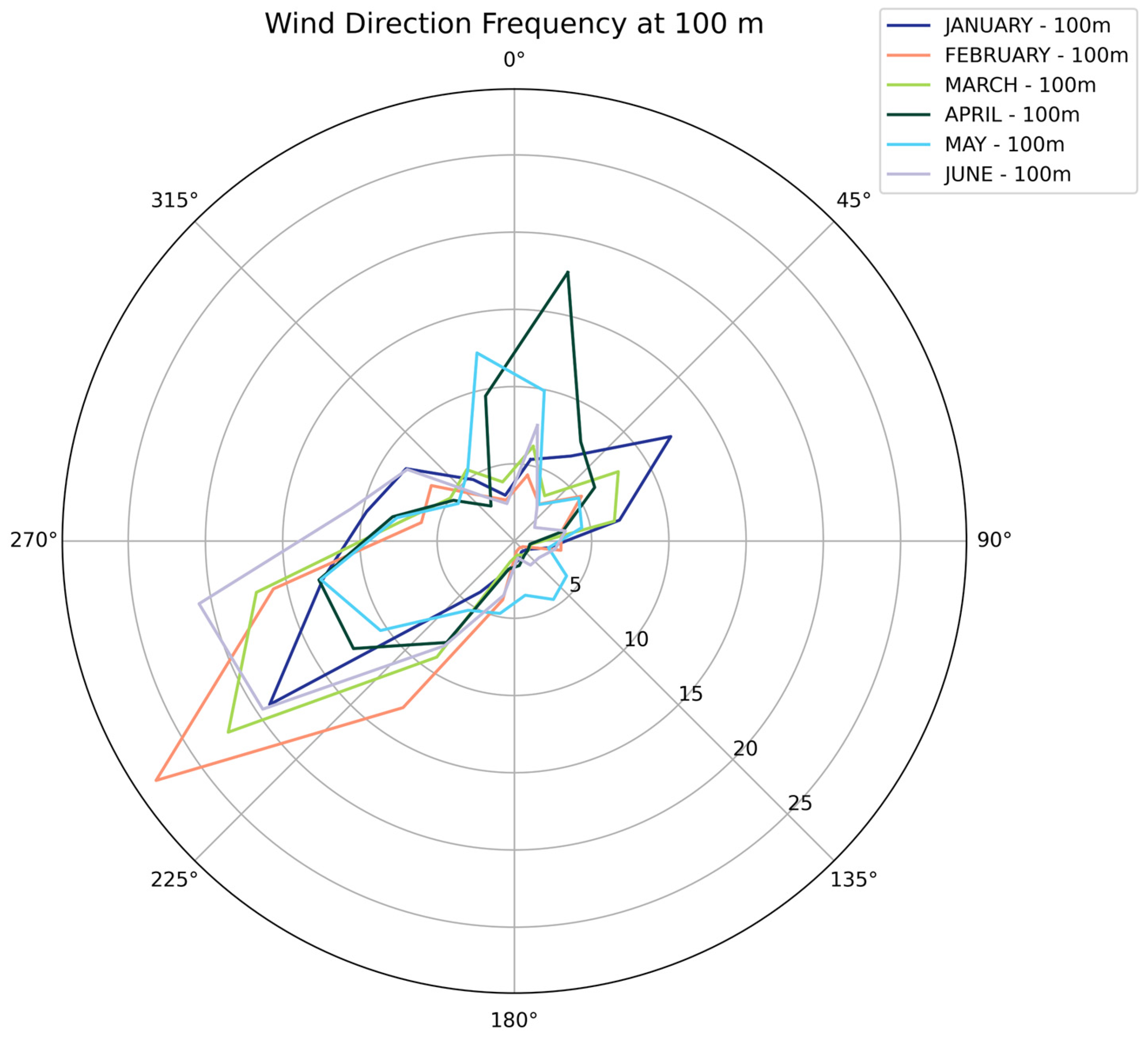

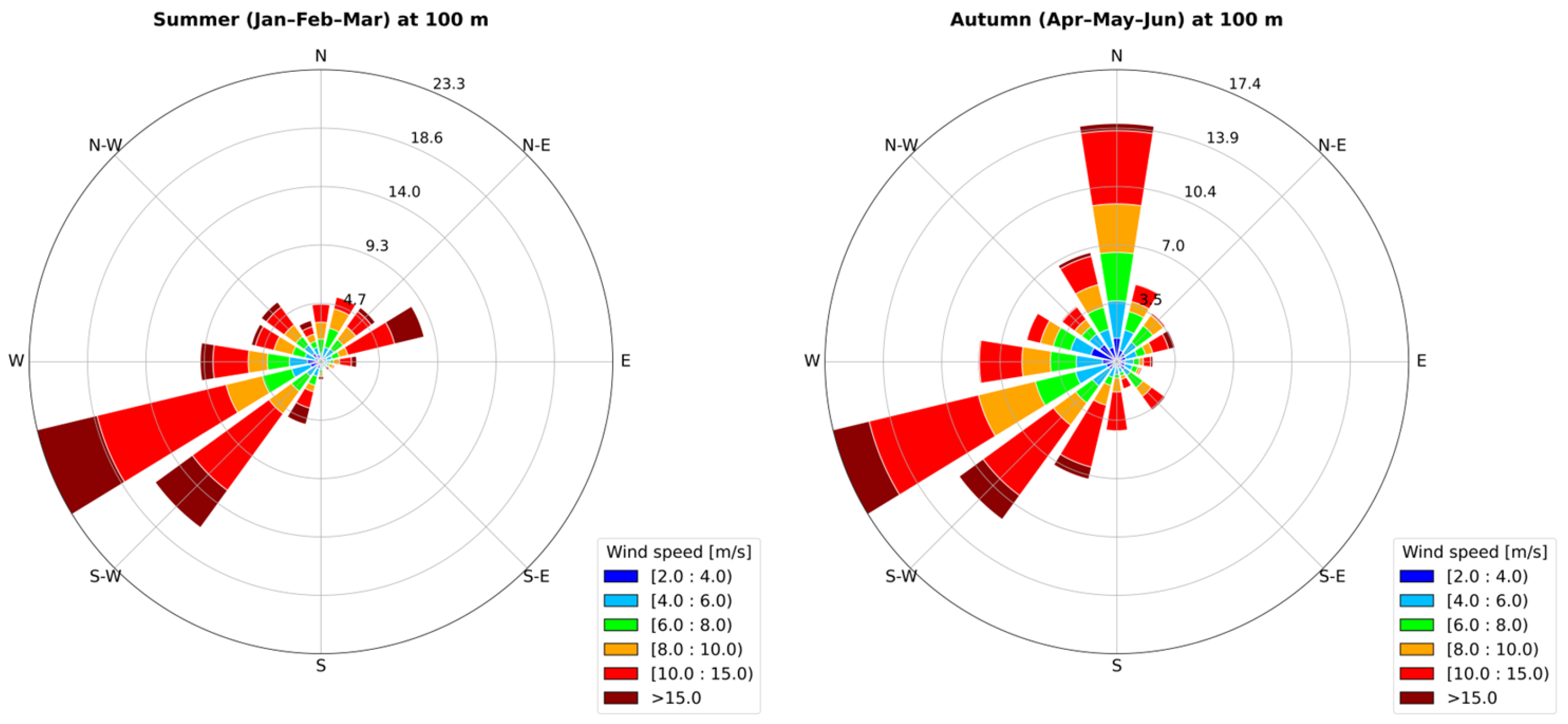

4.2. Seasonal Dynamics of Prevailing Winds at 100 m

4.3. Statistical Characterization of Wind Speed Distributions

4.3.1. Weibull Distribution Analysis

4.3.2. Lognormal Distribution as an Alternative Parametric Benchmark

4.3.3. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE): Non-Parametric Reference

4.4. From Wind Data to Power Output

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Archer, C.L.; Jacobson, M.Z. Evaluation of Global Wind Power. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, 2004JD005462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Navarrete, M.; Atencio, E. Renewable Wind Energy Implementation in South America: A Comprehensive Review and Sustainable Prospects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OLADE. Manual de Estadística Energética 2017; Organización Latinoamericana de Energía: Quito, Ecuador, 2017.

- Secretaría de Planeamiento Energético Estratégico. Balance Energético Nacional 2015; Ministerio de Energía y Minería: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016.

- Secretaría de Energía de la Nación (Argentina). Balances Nacionales: (PDF y XLS Hasta 2021); PDF and XLS through 2021; National Energy Balances: Ministerio de Economía: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021.

- Ministerio de Energía y Minería. Argentina Balances Energéticos Provinciales—Notas Metodológicas y Consolidación de La Información; Ministerio de Energía y Minería: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017.

- Oliva, R. Estudio Diagnóstico e Identificación de Proyectos Energéticos, Etapa I (EDIPE-Etapa I-SC). Final Report (V17-11-23 B3); Consejo Federal de Inversiones (CFI): Buenos Aires, Argentina; Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia Austral (UNPA): Santa Cruz, Argentina, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, T.R.; Bromwich, D.H. Reexamination of the Near-Surface Airflow over the Antarctic Continent and Implications on Atmospheric Circulations at High Southern Latitudes*. Mon. Weather Rev. 2007, 135, 1961–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V. Evaluación Del Potencial Eólico En La Patagonia. Meteorológica 1983, 14, 473–484. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, V. Atlas Del Potencial Eólico Del Sur Argentino; Segunda Edición; Centro Regional de Energía Eólica (CREE)—Centro Nacional Patagónico (CENPAT): Puerto Madryn, Argentina, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Albornoz, C.; Albornoz, S.; Oliva, R. Informe de Relevamiento del Recurso Eólico en Santa Cruz; Servicios Públicos Sociedad del Estado (SPSE), Universidad Nacional de La Patagonia Austral (UNPA): Caleta Olivia, Argentina, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de la Producción—Gobierno de Santa Cruz. Gobierno de Santa Cruz 2do Foro de Transición Energética Sostenible Santa Cruz 11 y 12/05/2023; Ministerio de la Producción—Gobierno de Santa Cruz: Santa Cruz, Argentina, 2023.

- Courtney, M.; Wagner, R.; Lindelöw, P. Testing and Comparison of Lidars for Profile and Turbulence Measurements in Wind Energy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkamp, C. Lidar: Range-Resolved Optical Remote Sensing of the Atmosphere; Springer Series in Optical Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-387-40075-4. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, E. From Fauna to Flames: Remote Sensing with Scheimpflug-Lidar. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuji, T.; Fukuchi, T. Doppler LiDAR Fundamentals. In Laser Remote Sensing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Veers, P.; Dykes, K.; Lantz, E.; Barth, S.; Bottasso, C.; Carlson, O.; Clifton, A.; Green, J.; Green, P.; Holttinen, H.; et al. Grand Challenges in the Science of Wind Energy. Science 2019, 366, eaau2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomi, I.; Vihma, T. Wind Gust Measurement Techniques—From Traditional Anemometry to New Possibilities. Sensors 2018, 18, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S. Atmospheric Acoustic Remote Sensing: Principles and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-429-12623-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sathe, A.; Mann, J.; Gottschall, J.; Courtney, M.S. Can Wind Lidars Measure Turbulence? J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2011, 28, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-12-1:2017; IEC 61400-12-1:2017—Wind Energy Generation Systems—Part 12-1: Power Performance Measurements of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Goit, J.P.; Shimada, S.; Kogaki, T. Can LiDARs Replace Meteorological Masts in Wind Energy? Energies 2019, 12, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Mohandes, M.A.; Alhems, L.M. Wind Speed and Power Characteristics Using LiDAR Anemometer Based Measurements. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2018, 27, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-12-1:2023; IEC 61400-12-1:2023—Wind Energy Generation Systems—Part 12-1: Power Performance Measurements of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Luna, F.; Quiroga, J.; Cortez, N.; Lescano, J.; Triñanes, P.; González, L.; Salvador, J.; Gonzalez, J.F.; Oliva, R.; Sofía, O.; et al. Estudios Básicos e Implementación de Sistemas de Medición Remota Para Relevamiento del Recurso Eólico e Integración y Operación del Equipo Lidar Adquirido. Energías Renov. Medio Ambiente 2024, 54, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- ZX Lidars. ZX 300 Deployment Guide, Issue 3.2; ZX Lidars: Ledbury, UK, 2022.

- ZX Lidars. ZX 300/M Configuration Guide, Issue 1.2; ZX Lidars: Ledbury, UK, 2022.

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python; AQR Capital Management: Austin, TX, USA, 2010; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubeyrie, L.; Celles, S. Windrose: A Python Library for Generating Wind Rose Plots. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 3, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZX Lidars. ZX 300/M Data Analysis Guide, Issue 1.21; ZX Lidars: Ledbury, UK, 2023.

- Gil-Bardají, M.; Puig, P. The TIMES Series: A Journey Through Time-Domain Wind Resource Assessment. Part 4: TIMES Using Python. Vortex FDC Blog. 2023. Available online: https://vortexfdc.com/blog/the-times-series-python/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Ahmed, M.I.; Pan, P.; Kumar, R.; Mandal, R.K. Wind Generation Forecasting Using Python. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Frontiers in Electrical and Electronic Technologies (ICEFEET), Patna, India, 10–11 July 2020; IEEE: Patna, India, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino, J.T.; Rejuso, M.V.; Villanueva, J.K.; Inocencio, L.C.; Rosario, M.; Ang, C.O. Development of a Wind Resource Assessment Framework Using Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model, Python Scripting and Geographic Information Systems. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Comput. Syst. Eng. 2015, 9, 1110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.Y.; Draxl, C.; Berg, L.K. Evaluating Wind Speed and Power Forecasts for Wind Energy Applications Using an Open-Source and Systematic Validation Framework. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwell, J.F.; McGowan, J.G.; Rogers, A.L. Wind Energy Explained: Theory, Design and Application; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-68628-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, J.A.; Mentado, D. A Continuous Bivariate Model for Wind Power Density and Wind Turbine Energy Output Estimations. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katinas, V.; Marčiukaitis, M.; Gecevičius, G.; Markevičius, A. Statistical Analysis of Wind Characteristics Based on Weibull Methods for Estimation of Power Generation in Lithuania. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, H. Wind Speed Model Based on Kernel Density Estimation and Its Application in Reliability Assessment of Generating Systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2016, 5, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ai, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Lu, D.; Shen, H. Short-Term Wind Power Prediction Based on Multiscale Numerical Simulation Coupled with Deep Learning. Renew. Energy 2025, 246, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguro, J.V.; Lambert, T.W. Modern Estimation of the Parameters of the Weibull Wind Speed Distribution for Wind Energy Analysis. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2000, 85, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.P. Performance Comparison of Six Numerical Methods in Estimating Weibull Parameters for Wind Energy Application. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S. Wind Power Resources Assessment at 10 Different Locations Using Wind Measurements at Five Heights. Env. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2022, 41, e13853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobočíková, I.; Sedliačková, Z.; Michalková, M. Application of Four Probability Distributions for Wind Speed Modeling. Procedia Eng. 2017, 192, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimourian, H.; Abubakar, M.; Yildiz, M.; Teimourian, A. A Comparative Study on Wind Energy Assessment Distribution Models: A Case Study on Weibull Distribution. Energies 2022, 15, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, J.A.; Ramírez, P.; Velázquez, S. A Review of Wind Speed Probability Distributions Used in Wind Energy Analysis: Case Studies in the Canary Islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 933–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.C.; Lackner, M.; Vogel, R.M.; Baise, L.G. Probability Distributions for Offshore Wind Speeds. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Hao, Z.; Hu, T.; Chu, F. Non-Parametric Models for Joint Probabilistic Distributions of Wind Speed and Direction Data. Renew. Energy 2018, 126, 1032–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houndekindo, F.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J. A Non-Parametric Approach for Wind Speed Distribution Mapping. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 296, 117672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W. Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice, and Visualization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-471-54770-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Wind Speed Distribution Selection—A Review of Recent Development and Progress. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, C.; Lässig, J.L.; Cogliati, M.G.; Bastanski, M.A. Wind Regime and Wind Power in North Patagonia, Argentina. Wind Eng. 2000, 24, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.R.B. Wind And Solar Power Systems: Design, Analysis, and Operation; CRC PRESS: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-47693-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rigel Ingeniería. Bicentenario Wind Farm I and II. 2021. Available online: https://www.rigel.com.ar/Proyectos/parque-eolico-del-bicentenario-i-y-ii/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- UL Solutions. Windographer (v.5.3.12) [Computer software]. Help Manual: Mean of Monthly Means; UL Solutions: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2024.

- Kuczyński, W.; Wolniewicz, K.; Charun, H.; Kuczyński, W.; Wolniewicz, K.; Charun, H. Analysis of the Wind Turbine Selection for the Given Wind Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCR Reporte de Sustentabilidad 2024; PCR. Available online: https://ceads.org.ar/pcr-presento-su-reporte-de-sustentabilidad-2024/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

| Measurement Technique | Measurement Principle | Typical Height Range | Spatial/Vertical Resolution | Intrusiveness | Suitability for Wind Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteorological mast (cup/Sonic anemometers) | Point measurement of wind speed and direction | Up to 80–120 m | Discrete (fixed sensor heights) | High (fixed infrastructure) | Reference method; limited for modern tall turbines |

| SODAR | Acoustic remote sensing using sound wave backscatter | ~30–200 m | Moderate (coarser vertical resolution) | Low | Useful for preliminary assessments; higher uncertainty |

| Doppler LiDAR | Laser-based remote sensing using Doppler shift or aerosol backscatter | ~20–200 m (or higher, model-dependent) | High (fine vertical resolution, continuous profiling) | Non-intrusive | High accuracy; IEC-compliant; well suited for modern wind projects |

| Turbine | Turbine Output | Percentage of Time at | Simple Mean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vestas V117-3.3 MW IEC IIA (100 m) | Valid Time Steps | Zero Power | Rated Power | Net Power (kW) | Net AEP (kWh/yr) | NCF (%) |

| 21,875 | 5.44 | 16.42 | 1634.8 | 14,320,649 | 49.54 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luna, M.F.; Oliva, R.B.; Salvador, J.O. Exploratory Analysis of Wind Resource and Doppler LiDAR Performance in Southern Patagonia. Wind 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010003

Luna MF, Oliva RB, Salvador JO. Exploratory Analysis of Wind Resource and Doppler LiDAR Performance in Southern Patagonia. Wind. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuna, María Florencia, Rafael Beltrán Oliva, and Jacobo Omar Salvador. 2026. "Exploratory Analysis of Wind Resource and Doppler LiDAR Performance in Southern Patagonia" Wind 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010003

APA StyleLuna, M. F., Oliva, R. B., & Salvador, J. O. (2026). Exploratory Analysis of Wind Resource and Doppler LiDAR Performance in Southern Patagonia. Wind, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/wind6010003