‘Uncomfortable and Embarrassed’: The Stigma of Gastrointestinal Symptoms as a Barrier to Accessing Care and Support for Collegiate Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Questionnaire

2.2.2. Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survey Findings

3.2. Interview Findings

3.2.1. GIS and ExGIS in Female Runners

3.2.2. The Stigma of ExGIS

3.2.3. Sport and Exercise Experiences of ExGIS

3.2.4. ExGIS Contributing Factors

3.2.5. Seeking Support for ExGIS

4. Discussion

4.1. Sex Differences in ExGIS

4.2. ExGIS Contributors

4.3. ExGIS Resources and Self-Management

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, R.J.S.; Snipe, R.M.J.; Kitic, C.M.; Gibson, P.R. Systematic review: Exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome-implications for health and intestinal disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.J.S.; Gaskell, S.K.; McCubbin, A.J.; Snipe, R.M.J. Exertional-heat stress-associated gastrointestinal perturbations during Olympic sports: Management strategies for athletes preparing and competing in the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. Temperature 2020, 7, 58–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijck, K.; Lenaerts, K.; Grootjans, J.; Wijnands, K.A.P.; Poeze, M.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Buurman, W.A. Physiology and pathophysiology of splanchnic hypoperfusion and intestinal injury during exercise: Strategies for evaluation and prevention. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G155–G168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, J.N.; Lydon, K.M.; O’Donovan, C.M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Madigan, S.M. More than a gut feeling: What is the role of the gastrointestinal tract in female athlete health? Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.; Khoo, A.; Rauch, C.; Snipe, R.M.J.; Camões-Costa, V.L.; Gibson, P.R.; Costa, R.J.S. Two weeks of repetitive gut-challenge reduce exercise-associated gastrointestinal symptoms and malabsorption. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.P.; Burini, R.C.; Jeukendrup, A. Gastrointestinal complaints during exercise: Prevalence, etiology, and nutritional recommendations. Sports Med. 2014, 44 (Suppl. S1), S79–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.W.K. Lower gastrointestinal distress in endurance athletes. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2009, 8, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokladny, K.; Zuhl, M.N.; Moseley, P.L. Intestinal epithelial barrier function and tight junction proteins with heat and exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhl, M.; Schneider, S.; Lanphere, K.; Conn, C.; Dokladny, K.; Moseley, P. Exercise regulation of intestinal tight junction proteins. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.P.; Burini, R.C. Food-dependent, exercise-induced gastrointestinal distress. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2011, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, S.K.; Taylor, B.; Muir, J.; Costa, R.J.S. Impact of 24-h high and low fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharide, and polyol diets on markers of exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome in response to exertional heat stress. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, D.M. Exit Gluten-Free and Enter Low FODMAPs: A Novel Dietary Strategy to Reduce Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Athletes. Sports Med. 2019, 49 (Suppl. S1), 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.; Mach, N. Exercise-induced stress behavior, gut-microbiota-brain axis and diet: A systematic review for athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2016, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.B. Perceived life stress and anxiety correlate with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in runners. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.M.; Petriz, B.; Marques, G.; Kamilla, L.H.; Franco, O.L. Is there an exercise-intensity threshold capable of avoiding the leaky gut? Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 627289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishima, S.; Kawamura, A.; Kawase, T.; Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Tsukara, T.; Inoue, R. Intensive, prolonged exercise seemingly causes gut dysbiosis in female endurance runners. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 68, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkemper, M.M.; Jarrett, M. Pattern of gastrointestinal and somatic symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinvels, G.; Goldsmith, E.; Blagrove, R.; Simpkin, A.; Lewis, N.; Morton, K.; Suppiah, A.; Rogers, J.; Ackerman, K.; Newell, J.; et al. Prevalence and frequency of menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with availability to train and compete: A study of 6812 exercising women recruited using the STRAVA exercise app. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 55, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judkins, T.C.; Dennis-Wall, J.C.; Sims, S.M.; Colee, J.; Langkamp-Henken, B. Stool frequency and form and gastrointestinal symptoms differ by day of the menstrual cycle in healthy adult women taking oral contraceptives: A prospective observational study. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolić, P.V.; Sims, D.T.; Hicks, K.; Thomas, L.; Morse, C. Physical Activity and the Menstrual Cycle: A Mixed-Methods Study of Women’s Experiences. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2021, 29, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Knight, C.J.; Forrest, L.J. Elite female athletes’ experiences and perceptions of the menstrual cycle on training and sport performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.; Barlow, D.; Jewell, D.; Kennedy, S. Do gastrointestinal symptoms vary with the menstrual cycle? BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998, 105, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, P.; Sawin, K.J. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook 2009, 57, 217–225.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman-Green, D.; Jaser, S.; Martin, F.; Alonzo, A.; Grey, M.; McCorkle, R.; Redeke, N.S.; Reynolds, N.; Whittemore, R. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2012, 44, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, R.B.; Sanfilippo, J.L.; Domeyer, T.J.; Hetzel, S.J.; Brooks, M.A. Eating Behaviors and Nutrition Challenges of Collegiate Athletes: The Role of the Athletic Trainer in a Performance Nutrition Program. Athl. Train. Sports Health Care 2018, 10, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, D.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; Shing, C.M.; Ahuja, K.D.K.; Fell, J.W. Exploring the popularity, experiences, and beliefs surrounding gluten-free diets in nonceliac athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, E.L.; Wright, C.J.; Kirkpatrick, C.M. Nutrition practices and knowledge among NCAA Division III football players. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.B. Nutrition behaviors, perceptions, and beliefs of recent marathon finishers. Phys. Sportsmed. 2016, 44, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; 132p. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, B.; Stellingwerff, T.; Hodgson, A.B.; Randell, R.; Pöttgen, K.; Res, P.; Jeukendrup, A. Nutritional intake and gastrointestinal problems during competitive endurance events. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, L.A.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.M.; Lee, S.Y. Questionnaire on Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Symptom Management Among Endurance Athletes Is Valid and Reliable. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 3281–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.B.; Fearn, R.; Pugh, J. Occurrence and Impacts of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Team-Sport Athletes: A Preliminary Survey. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2023, 33, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feingold, J.H.; Drossman, D.A. Deconstructing stigma as a barrier to treating DGBI: Lessons for clinicians. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, M.; Whorwell, P.J.; Vasant, D.H. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: A taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, P.; Parr, H.; Barberio, B.; Black, C.J.; Savarino, E.V.; Ford, A.C. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. The Athlete’s Gut: The Inside Science of Digestion, Nutrition, and Stomach Distress; VeloPress: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020; 320p, Available online: https://www.amazon.ca/Athletes-Gut-Digestion-Nutrition-Distress/dp/194800710X (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Wilson, P.B.; Russell, H.; Pugh, J. Anxiety may be a risk factor for experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms during endurance races: An observational study. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, C.T.; Aydin, C.G.; Ersoy, G. The effect of nutrition education sessions on energy availability, body composition, eating attitude and sports nutrition knowledge in young female endurance athletes. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1289448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, K.; Erdman, K.A.; Stadnyk, M.; Parnell, J.A. Dietary supplement usage, motivation, and education in young, Canadian athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, K.A. A Lifetime Pursuit of a Sports Nutrition Practice. Can. J. Diet Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.C.; Gaul, C.; Janzen, J. Education and training of sport dietitians in Canada: A review of current practice. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2011, 72, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | All Participants (n = 96) | Females (n = 73) | Males (n = 23) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 19.1 (3.9) | 19.0 (3.9) | 19.2 (3.7) | 0.96 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 20.7 (3.0) | 20.3 * (2.9) | 22.1 (2.7) | 0.004 |

| Primary sport, n (%) | ||||

| Varsity | 52 (53) | 39 (54) | 12 (52) | 0.22 |

| Club | 44 (46) | 33 (46) | 11(48) | |

| Perceived health, n (%) | ||||

| Excellent or very good | 68 (71) | 50 (69) | 18 (78) | 0.68 |

| Good | 24 (25) | 20 (27) | 4 (18) | |

| Fair or poor | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | |

| Perceived food allergy, n (%) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (9) | 0.14 |

| Perceived food intolerance, n (%) | 21 (22) | 20 * (27) | 1 (5) | 0.02 |

| Quantitative Survey Results (n = 96) | Qualitative Follow-Up Explaining Quantitative Results (n = 4) | Integration |

|---|---|---|

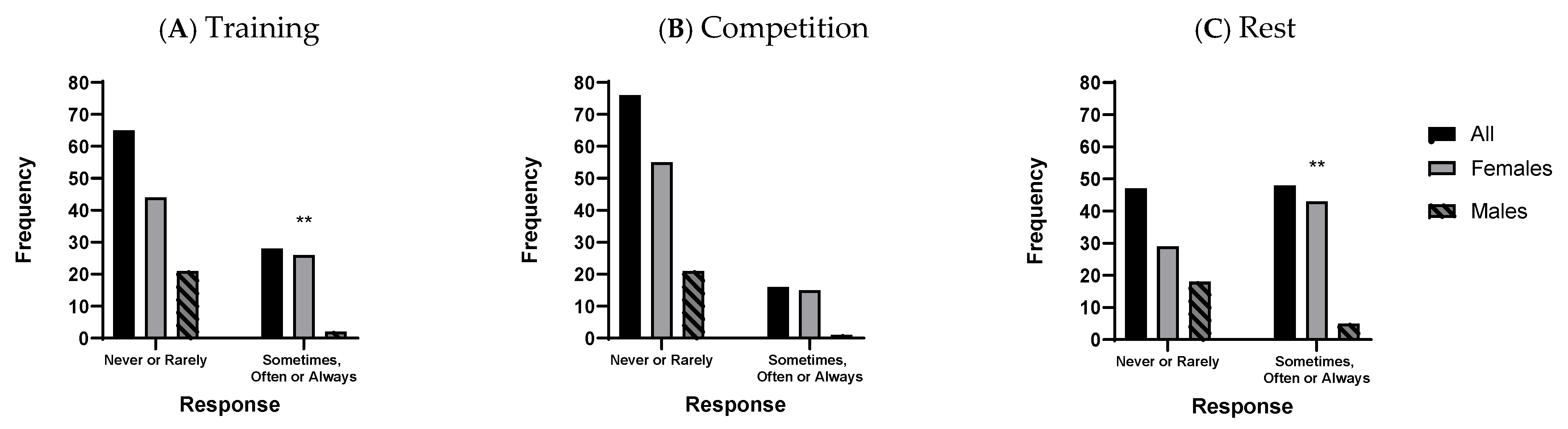

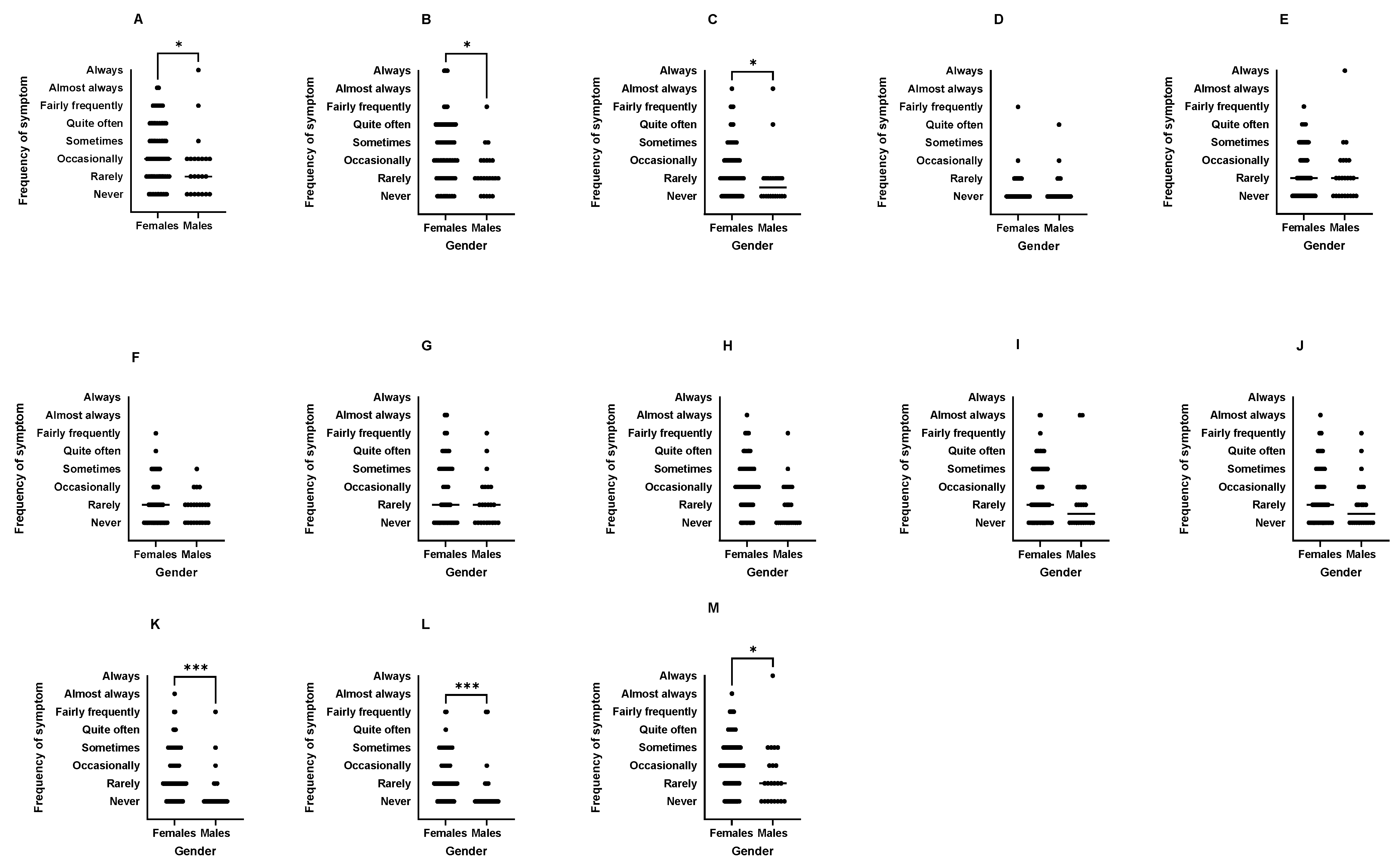

| Female athletes had higher occurrence of GIS at rest (60%) and during training (37%) than males (22%, 9%, respectively; p < 0.01) and were more likely to report food intolerance. Female athletes also perceived higher occurrence of specific upper and lower GIS during exercise than males (p < 0.05). GIS interruptions to exercise were most commonly by runners and team sport athletes (e.g., rugby, hockey). | Those interviewed were female runners despite an active and long period of recruitment across 11 different sports. | Female runners accept ExGIS as a normal and/or expected part of running culture, possibly limiting their perceptions of seeing it as a problem. The stigma of ExGIS may hinder interview recruitment and openness to seek support. Sex differences in ExGIS require further research. |

| Type of exercise, dietary factors, and stress or anxiety were implicated in ExGIS. A total of 15.6% of athletes reported that sport nutrition products (mainly nutrition bars) contributed to ExGIS, while 36.5% were unsure of a possible link with these products. | Events of long duration, high intensity, and/or pre-event anxiety contributed to ExGIS. Athletes indicated using “trial and error” with diet (restriction) and hydration to manage unpredictable symptoms. | Athletes continually managed ExGIS through dietary modification with inconsistent results. University-tier athletes may lack awareness of and/or access to sport medicine and sport dietetic professionals to diagnose and manage ExGIS effectively. |

| Top sources of nutrition information cited were dietitians and coaches. Sources of information used most frequently for ExGIS included family, friends or none. Only 12.6% of respondents sought medical guidance for ExGIS. | Athletes indicated that resources specific to ExGIS were unavailable, that they were unsure where to go for support, or that ExGIS was a normal occurrence for runners. Athletes had not sought advice from a medical professional outside of their family. Athletes used family, friends, teammates, the internet for support, though most felt the strategies they found were unhelpful. | Limited understanding of ExGIS in combination with uncertainty in finding accessible and effective resources may have led to less support seeking behaviours. Athletes with GIS at rest, in particular, should be referred for medical evaluation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamieson, J.A.; Olynyk, C.; Harvie, R.; O’Brien, S. ‘Uncomfortable and Embarrassed’: The Stigma of Gastrointestinal Symptoms as a Barrier to Accessing Care and Support for Collegiate Athletes. Dietetics 2025, 4, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4010011

Jamieson JA, Olynyk C, Harvie R, O’Brien S. ‘Uncomfortable and Embarrassed’: The Stigma of Gastrointestinal Symptoms as a Barrier to Accessing Care and Support for Collegiate Athletes. Dietetics. 2025; 4(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamieson, Jennifer A., Cayla Olynyk, Ruth Harvie, and Sarah O’Brien. 2025. "‘Uncomfortable and Embarrassed’: The Stigma of Gastrointestinal Symptoms as a Barrier to Accessing Care and Support for Collegiate Athletes" Dietetics 4, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4010011

APA StyleJamieson, J. A., Olynyk, C., Harvie, R., & O’Brien, S. (2025). ‘Uncomfortable and Embarrassed’: The Stigma of Gastrointestinal Symptoms as a Barrier to Accessing Care and Support for Collegiate Athletes. Dietetics, 4(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4010011