1. Introduction

The rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have been increasing, and in 2020 they collectively accounted for 71% of total deaths worldwide [

1]. The most common NCDs are cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer [

1]. According to the World Health Organization, these chronic diseases are mainly due to globalization, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity and an aging population [

2]. A healthy diet that protects against NCDs is characterized by a high intake of fruits and vegetables, wholegrains, nuts, legumes and seeds; as well as a low intake of red/processed meats and refined starches [

3]. The Mediterranean dietary pattern (MDP) is an example of such a dietary pattern. The MDP is characterised by a high content of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, fish and olive oil; low to moderate content of dairy products, poultry and eggs; low in saturated fatty acids (SFA), red and processed meats; as well as regular moderate intake of red wine with food [

4]. It also emphasises regular social interaction at meals and physical activity. The MDP has been linked to decreased risks of various chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, obesity, hypertension, diabetes and cognitive decline [

5,

6,

7]. Some mechanisms by which the MDP decreases the risks of NCDs is by reducing metabolic risk factors, including oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as improved blood pressure, lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity [

8,

9].

When looking into an individual’s dietary intake, it is important to understand factors that affect eating behaviours. Eating behaviour is governed by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include, age, sex and genetics, whereas, extrinsic factors include sociocultural considerations, food availability, food preferences, socioeconomical status, eating attitudes and knowledge [

10]. Two of the extrinsic factors that can be changed/improved are nutritional knowledge and eating attitudes. Nutritional knowledge is a personal interpretation of the information and skills that an individual develops either through education or life experiences [

11]. Attitudes towards foods involve emotions and beliefs; they are mostly reported as being a positive or negative attitude towards a certain dietary guideline [

12].

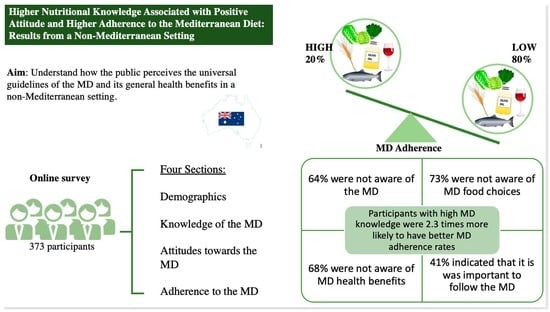

When reviewing the literature, published studies have focused on examining the association between adherence to the MDP and the risk of various health issues, such as, cancer, cognition, mortality, and diabetes. A few studies have investigated whether people know what the MDP is, or if they are aware of its beneficial effects; and few have investigated the relation of knowledge and attitude to adherence in both Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean countries. The main aim of this study is to understand how people living in a non-Mediterranean society perceive the universal characteristics of the MDP and its general health benefits. A secondary aim is to identify determinants that may hinder or promote the adoption of a MDP in a non-Mediterranean setting.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population with 373 participants in this study. Most were females (n = 303; 81%) of less than 40 years old (n = 307; 82%). For educational level, 65 individuals had finished a school degree, while 290 had university degrees. More than half of the total sample had lived in Australia for more than 10 years and were of non-Mediterranean origins.

Table 2 summarizes all three Mediterranean dietary knowledge scores: Guidelines, Food choices, Health benefits as well as the total score among adults in Brisbane, Queensland. The detailed knowledge scoring tables can be found in the

supplementary material (Tables S1–S3). The mean knowledge score of MDP guidelines was 5.5 ± 2.4 points out of the 12-point score, and around 37% of participants scored above the 75th percentile for this score. For the 11-point food choices score, the mean was 8.4 ± 1.7 points and 53% and 27% of the sample scored higher than the 50th and 75th percentile, respectively. For the health benefits of the MDP, the average score for the cohort was 3.6 ± 2.1 points and 32% of participants scored higher than the 75th percentile. For the overall knowledge score ranging from 0–31 points, the mean score for participants was 17.5 ± 4.5 points and 25% scored above the 75th percentile.

Table 3 includes the means and standard deviations of the four Mediterranean dietary attitudes scores: Perceived importance, Food preferences, Perceived barriers, and Self-confidence among adults living in Brisbane. The mean score of the 21-point perceived importance score of the MDP was 18.3 ± 2.8 points and 41% of participants scored above the 75th percentile. A total of 207 (55%) participants believed that it is important to follow the general dietary guidelines of the MDP (

Supplementary material, Table S4). In contrast, only 28% of participants scored above the 75th percentile for the food preferences section, with a mean score of 33.1 ± 5.7 points for all the sample out of the 42-point score. Most participants reported that they enjoyed the flavors of fish, chicken, nuts, fruits, dairy and whole-grain products (

Supplementary material, Table S5). A total of 19% of our sample found it difficult to adhere to the MDP. A considerable proportion of participants (33%) found it hard to consume fish regularly (

Supplementary material, Table S6). From a total of 127 participants, 34%, indicated they felt confident to follow the MDP and its various dietary components (

Table S7).

To measure participant adherence to the MDP, the PREDIMED score was calculated. The 14 single components of the score are shown in

Table 4. More than 66% of the respondents used olive oil as their primary source of fat; however, only 4% met the daily recommended dose. While 79% of participants adhered to the recommended intake amounts of 2 or more servings of vegetables per day, only 29% of participants adhered to the fruit recommendation of 3 or more servings a day. Over 90% of participants were consuming <1 serving of red meat per day and <1 serving/day of butter, margarine, or cream. Lastly, a small portion of the sample adhered to the recommended intakes of fish (12%), legumes (23%) and nuts (26%).

Linear regression analysis was used to determine possible associations between the total MDP knowledge score and attitudes scores towards the MDP. Beta estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the associations were reported in

Table 5. Results show that total knowledge score was significantly associated with all attitude scores. These results show that participants with higher knowledge also had higher confidence to follow the MDP, more enjoyment of the MDP flavours and higher perceived importance of consuming the MDP. Conversely, the knowledge score was inversely associated with perceived barriers; hence, lower knowledge scores were associated with more difficulty with adhering to the MDP.

Table 6 shows participants’ demographics across all four attitudes scores towards the MDP and its dietary components using ANOVA testing. Age was significantly associated with all scores: perceived importance, food preferences, perceived barriers, self-confidence. As people aged, they perceived the diet was more important, they had a higher preference for the MDP, reported fewer barriers, and had more confidence to follow the MDP. Females, compared to males, believed it was more important to follow the MDP and were more confident to follow this diet (

p = 0.02 and <0.01, respectively). Education was significantly associated with food preference score and a borderline significance association was observed with the perceived importance score. Participants from Mediterranean origins also had significantly higher scores for perceived importance and food preferences (

p < 0.01) than those from non-Mediterranean origins.

Most participants, 81%, scored less than 9 points on the 14-point PREDIMED score. The PREDIMED score was stratified across all four knowledge scores. The PREDIMED score was divided into low versus high adherence and knowledge scores were also divided into low versus high adherence (

Table 7). Participants with higher total MDP knowledge score were 2.3 times more likely to have higher PREDIMED scores (

p = 0.002). Similarly, participants with higher knowledge of MDP guidelines and food choices were more likely to have higher PREDIMED scores, OR 2.6 and 3.0 respectively. However, PREDIMED scores were not associated with knowledge of MDP health benefits.

4. Discussion

This study exhibits a comprehensive overview on people’s knowledge and attitudes towards the MDP in a sample of Australians living in Brisbane, Queensland. The aim of this study was to understand how individuals from a multi-ethnic non-Mediterranean community perceive the MDP and factors that may affect their abidance to this diet. Most participants in our study were female young adults, aged <40 years of age, who had lived in Australia for over 10 years. Similarly, most participants had high educational levels and university degrees. The main findings of this study are: (1) less than half of our sample were aware of the Mediterranean dietary guidelines, food choices and health benefits; (2) Most of the sample agreed that it is important to follow the MDP; (3) 20% of participants were adhering to the MDP; (4) knowledge about and attitudes towards the MDP were significantly associated with each other; and (5) adherence to the MDP was significantly associated with knowledge.

A total of 25% of the sample had high overall knowledge about MDP composition compared with around 40% of samples reported in Mediterranean countries [

28]. Knowledge about the MDP guidelines and food choices seemed to play a role in individuals’ dietary intake where higher knowledge was associated with higher adherence. Equivalent results were observed in other studies; for example, participants that were familiar with the MDP were four times more likely to adhere to it [

29]. Another study also reported that individuals with higher levels of nutrition education seemed to adhere more the MDP [

30]. Additionally, an intervention study showed that nutritional education sessions about the MDP significantly improved adherence to the MDP between pre- and post-intervention groups [

31]. However, it is important to note that nutritional education does not always translate into the adoption of healthy dietary patterns [

32] because dietary intake is affected by the interaction of several environmental, social, and intrinsic factors [

10].

The attitudes scores were all significantly associated with the total knowledge score about the MDP. Sociodemographic factors that seemed to affect the attitudes scores were, age, gender, and education. In the present study, all attitude scores were higher with increasing age. Hence, younger adults were more likely to believe that it was not important to follow the MDP, disliked the MDP flavours, found it difficult to adhere to it and were less confident to follow it. This is in line with other studies that reported that young adults were less likely to follow a healthy diet because they do not seem to have a positive attitude towards it [

33]. Although our results indicate that 41% of participants perceived it as important to follow the MDP, a recent study, also conducted in Australia, reported much higher rates, as 96% participants perceived adherence to the MDP as helpful [

34]. Scanell et al.’s methodology was quite different than the one used in the current study, they used only five open-ended questions to assess attitudes, barriers, and enablers to following the MDP. This qualitative assessment could have led to participants reporting their perceived attitudes towards the MDP as opposed to their actual attitude.

Regional and geographical differences in adherence to the MDP do exist between Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean countries, and within Mediterranean countries [

35,

36]. Adherence to the MDP in Mediterranean countries can range anywhere from 20% to 70% [

37,

38]. In our sample, 19% of participants were considered as having good adherence to the MDP. Our results are in line with other studies conducted in Australia that reported good adherence to the MDP between 13% and 27% [

39,

40,

41,

42]. A study in Spain, that also included young adults, reported that 24% of their sample had “good adherence” to the MDP as measured by the PREDIMED score [

43].

As for possible barriers to adherence to the MDP, participants reported that it was difficult to consume fish and legumes regularly. Qualitative data revealed that participants lacked recipe ideas, specifically about cooking legumes, and needed some more education around this area which might help them increase adherence to the MDP. Our findings have identified similar trends to those previously reported by Kretowicz and co-workers [

44]. Although 66.2% of the sample were using olive oil as the main source of fat, only 3.8% of them met the recommended amount for olive oil intake. Our sample reported difficulty in consuming olive oil mainly due to the cost of it, so intake of olive oil in Mediterranean countries could be higher because it was less expensive there [

37]. Similarly, our sample seemed to find it difficult to adhere to fish recommendation for reasons also related to costs. While most of our sample agreed that it is important to eat fish and liked its flavour, many of them found it difficult to eat it regularly. As reported by them, fish seemed more expensive than other animal protein sources hence they consumed it less often. This is supported by another study in the non-Mediterranean region that reported that fish and olive oil were among the MDP components associated with a higher cost of adherence [

45].

A considerable percentage of the sample were not confident to cook at home on most days of the week due to time constraints, which follows results from another Australia study by Scannell et al. [

34]. This might have affected their rates of adherence to the MDP because cooking has been shown to play a role in adopting a healthy diet [

46]. This might be an intervention focal point for increasing adherence to the MDP among young Australians in the future.

This study is not without limitations. This is of a cross-sectional design; hence no causality could be established. Given that data collection took place online, this saved time and costs of conducting the surveys. No IP addresses were traced or saved, so participants anonymity was ensured. Face-to-face interviews allow interviewers to address the participant’s concerns and help them better understand the survey, however, this limitation was addressed in part by adding an email address that participants could use to send all their comments/concerns. Online data collection is a useful method when recruiting students/employees and young adults, given that this age group has higher access to online platforms and better computer skills [

47]. Online data collection prevented face-to-face interaction between the interviewer and participants; hence, the participants responses were not influenced in any way by the interviewer. Additionally, email surveys may result in more representative samples by bypassing geographical boundaries [

48].

Online surveys are known to have lower response rates than face-to-face surveys and participants are more likely to exit in the middle of the survey [

49]. We tried to increase response rates by providing individuals with incentives. To increase response rates, we provided individuals with prepaid voucher incentives which have shown to increase response rates [

50]. Participants were aware that they were being compensated for their time, so they might rush the survey to maximize their pay to time ratio. This was resolved by recording the time of each participant. This survey took on average 30 min to complete which might have affected response rates. Studies have shown that there is an inverse association between the survey’s length and its response rate; short surveys, less than 15 min, usually have the highest response rates [

49]. To overcome this, we did not display a survey progress bar because this has shown to aid in increasing completion rate [

51]. This survey also limited the use of open-ended questions because such questions might increase drop-out rates. Additionally, time-consuming questions were placed at the very end of the survey, which also helps with completion rate [

49]. Although we aimed for a 1:1 ratio of males and females in our study, this was not the case. This is comparable to other studies, where females are usually more likely to fill out a survey than their male peers [

51]. Lastly, most participants in the present study were young adults, which could make it harder to generalize our results to the Australian population. However, studies show that older individuals are more likely to adhere to the MDP [

52,

53] and have a more positive attitude towards the MDP that younger individuals [

33]. This indicates that actual rates of adherence to the MDP and rates of positive attitudes towards it could be even higher than results reported in this paper. Lastly, the study was conducted in one Australian city, Brisbane, it would be interesting to conduct it on a nationally based larger scale study to be able to generalize the results.

To our knowledge, this is the first Australian study to correlate the relationships between knowledge, attitudes and practices towards the MDP. This study also highlighted some future intervention strategies such as, increasing awareness to the MDP, and provide individuals the right tools to aid adherence to this dietary pattern. For example, some cooking or meal preparation techniques could increase adherence among working individuals; additionally, teaching people to eat seasonally and maximize usage of foods bought would help decrease the cost of adherence. This paper added to the literature key factors that might hinder adherence to the MDP in a multi-ethnic non-Mediterranean country.