1. Introduction

Axions are hypothetical pseudoscalar particles originally postulated as a consequence of the Peccei–Quinn solution to the strong CP problem in QCD [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Beyond their role in particle theory, axions and axion-like particles (ALPs) are compelling dark matter (DM) candidates and a target of broad experimental effort [

5]. The QCD axion mass

is related to the axion–photon coupling

, enabling photons to convert into axions (and vice versa) in the presence of strong electromagnetic fields [

6,

7].

The strongest laboratory limits to date were achieved by haloscope experiments developed over the past 40 years in the μeV range, which exploited resonant microwave cavities immersed in strong magnetic fields [

8,

9]. However, such searches implicitly rely on assumptions about the local axion DM density, which is poorly constrained and may deviate from the canonical galactic average [

10]. Approaches that do not assume axions as CDM, such as light-shining-through-wall (LSW) experiments or precision polarization measurements, have complementary sensitivity but remain well above the QCD axion band [

11,

12]. Moreover, the axion mass range at the level of

is largely unexplored by direct detection experiments (with the exception of CAST [

13]), since for cavity-based searches, the resonance frequency scales inversely with the cavity volume, making it practically impossible to reach the required frequencies without severely reducing sensitivity.

In this paper, we present the first prototype of Weakly Interacting Sub-eV Particles (WISP) Searches on a Fiber Interferometer (WISPFI), a novel laboratory scheme designed to probe photon–axion conversion inside a waveguide. The concept is based on a Mach–Zehnder interferometer in which one arm is exposed to a strong transverse magnetic field while the other serves as a reference. Operating the interferometer close to a dark fringe minimizes the contribution of laser shot noise (SN) [

14], thereby enhancing sensitivity. A photon amplitude reduction in the magnetized arm would indicate photon–axion conversion via the Primakoff effect [

15].

In the prototype currently under development at the University of Hamburg, Germany, the sensing arm incorporates a hollow-core photonic crystal fiber (HC-PCF). These fibers utilize a photonic bandgap cladding to confine light within a hollow, gas-filled core, where the guided mode can achieve an effective refractive index . This property enables resonant photon–axion conversion at real axion masses, a key requirement that cannot be met with conventional dielectric fibers. In the prototype, a ∼1 -long HC-PCF segment inside the magnetic field serves as the interaction region, operating at standard atmospheric pressure conditions and thus probing a fixed axion mass of approximately 50 meV. In the envisioned full-scale WISPFI, the probed mass will become tunable in the ∼28 meV to 100 meV range by adjusting the gas pressure inside the HC-PCF, which modifies of the propagating mode.

This waveguide-based, resonant detection scheme opens a new model-independent experimental window at the 50 meV mass scale and serves as a test bench for the final design and realization of a future full-scale WISPFI experiment.

2. Photon–Axion Mixing and Resonant Conversion

The photon-to-axion conversion probability along the propagation direction

z is [

7]:

where the mixing angle

and oscillation wave number

determine the amplitude and periodicity of the oscillations, respectively. The mixing angle is obtained by diagonalizing the photon–axion mixing matrix with the off-diagonal coupling term

(also known as the mixing energy):

where

is the photon–axion transfer momentum,

is the photon energy, and

and

are the photon and axion momenta in the medium, respectively.

In the same way, we can define the oscillation wavenumber in terms of these two parameters:

Under resonant conditions, when the photon and axion momenta match

), the mixing angle reaches

, maximizing the conversion probability. Under this limit, the oscillation wave number reduces to

, and for small probabilities (

), the conversion probability simplifies to

The resulting axion mass that can be probed for a given effective refractive index

of the medium is given by the following equation:

This resonance condition cannot be achieved in waveguides like standard dielectric fibers, which rely on index-guiding mechanisms and have

. However, HC-PCFs can guide light through a low-index gas-filled hollow core surrounded by a photonic bandgap cladding with a higher index, resulting in an effective mode index

[

16,

17]. This property allows the formation of real axion masses that satisfy the resonance condition. Combined with their high laser damage threshold [

18], HC-PCFs are an attractive platform for high-sensitivity axion searches [

19].

Based on Equation (

5), the effective mode index of the guided mode,

, determines the axion mass that can be resonantly probed. The real part of the propagation constant

can be analytically approximated via Marcatili’s formula, which is based on a simplified model of a cylindrical hollow-core fiber [

20]:

where

is the fiber core radius,

is the refractive index of the gas filling the core,

is the wavelength,

T the temperature, and

p the pressure. For higher accuracy, especially in fibers with complex geometries,

can be computed using finite-element method (FEM) simulations that account for the detailed fiber structure.

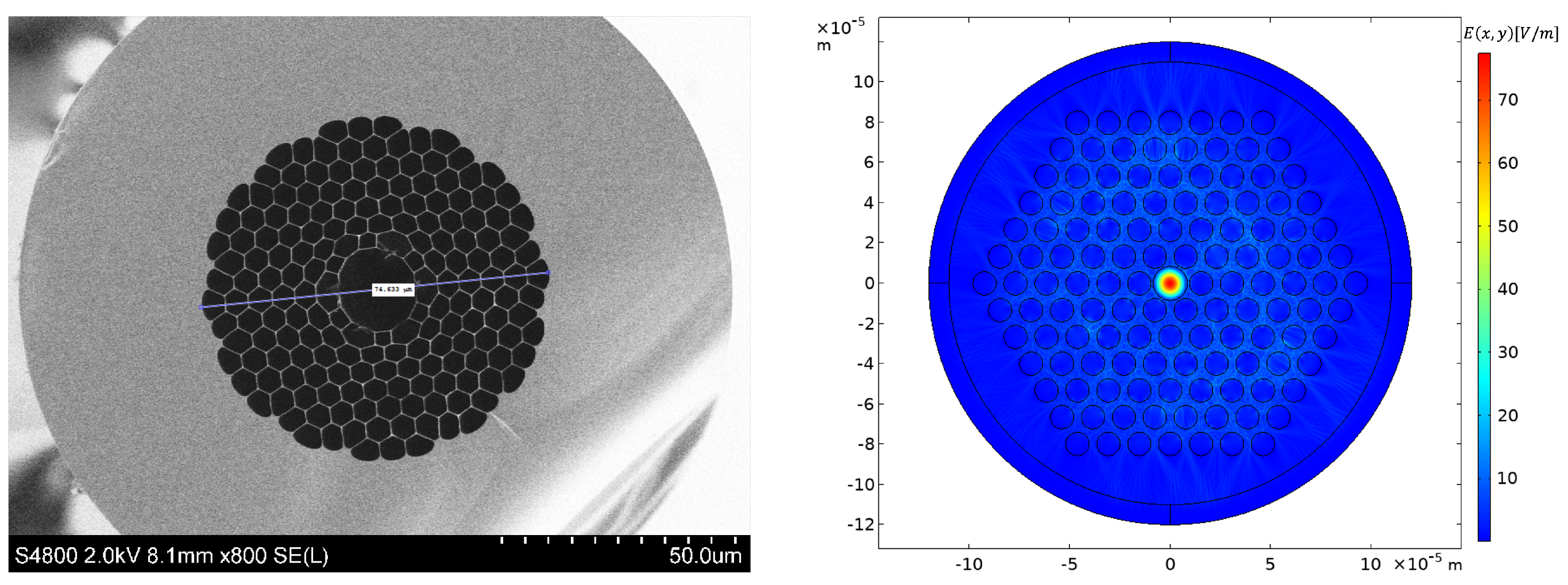

As we will see in

Section 4, in the WISPFI prototype, the sensing arm incorporates a HC-PCF with a core radius of

μm (

Figure 1 Left). The effective mode index of this fiber is computed using FEM in COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS 6.1 (

Figure 1 Right), taking into account its actual geometry with six rings of air-holes. This precise determination of

sets the specific axion mass that can be probed under standard atmospheric pressure conditions and provides a fixed test point for experimental development.

3. Principles of Phase-Modulated Interferometry

The key idea of WISPFI is to detect small axion-induced photon losses by converting them into a measurable modulation at a known frequency. Here, we illustrate the principle for the WISPFI prototype, which employs a Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI) with a phase-modulated input.

Light is injected into input port 1 of the interferometer, while input port 2 remains dark. The input field is as follows:

where

is the modulation index,

is the modulation frequency, and

is the carrier frequency. The phase modulation generates sidebands around the carrier, which can be expanded using the Jacobi–Anger identity:

The expansion can then be truncated to the carrier and the first-order sidebands (

):

At the first 50:50 beam splitter,

the field is split into sensing (

) and reference (

) arms:

The sensing arm has a length

and is exposed to the magnetic field, where photon–axion conversion occurs. The reference arm has a length

and remains unperturbed. After propagation, the fields in the two arms are given as shown below:

where

is the photon–axion conversion probability,

is the carrier wavenumber, and

is the modulation wavenumber.

The two arms are recombined at the second beam splitter:

To suppress the large carrier background and maximize sensitivity to small amplitude changes, the interferometer is locked closely to a dark fringe for the carrier. This ensures destructive interference of the carrier at the output port, thereby reducing laser SN. The dark-fringe conditions are as follows:

where

and

are small phase errors due to path-length mismatch. In practice, we consider only the carrier phase error

to be significant.

With these conditions, the power at the output dark-port (port 1) becomes

The first term corresponds to a large oscillation from sideband self-interference, while the second is a small modulation proportional to , arising from carrier–sideband mixing.

Finally, the axion signal is isolated by demodulating

at frequency

(e.g., with a lock-in amplifier; see

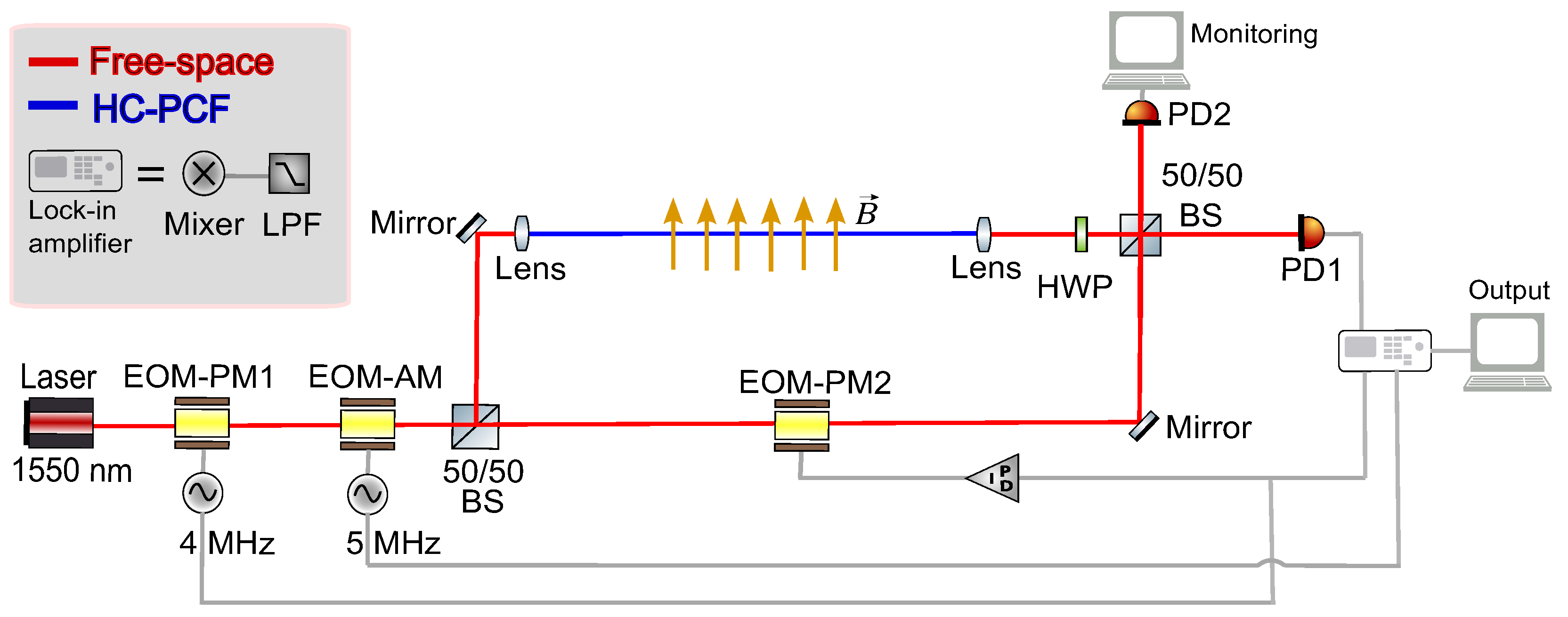

Figure 2). The time-averaged demodulated signal is

which separates the axion-induced contribution from the background noise. In practice, the axion signal detection involves comparing the spectra recorded by the output dark-port photodiode over long integration times between the

, where photon–axion conversion occurs, and

, where no conversion is present. This demonstrates how phase modulation and dark-fringe operation together convert a small photon–axion conversion probability into a measurable signal.

4. Experimental Setup

The WISPFI prototype is designed to detect small axion-induced photon amplitude changes using a partial free-space MZI. As discussed in

Section 3, phase modulation allows the interferometer to be locked near the dark fringe, while a dedicated amplitude modulation frequency can be used to isolate axion-induced amplitude changes from other noise sources. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in

Figure 2.

The interferometer is driven by a high-power 2 , 1550 laser. The beam initially passes through a resonant phase electro-optical modulator (EOM-PM1) operating at 4 , which provides the frequency reference for phase-locking the interferometer close to the dark fringe. A separate broadband phase EOM (EOM-PM2) in the sensing arm compensates for phase variations between the two interferometer arms. The error signal from the output dark-port photodiode (PD1) is demodulated at the phase-lock frequency of 4 and low-pass filtered with a 10 bandwidth before being fed into a PID loop controlling the broadband EOM. This stabilizes both the phase and the amplitude working point near the dark fringe.

After the EOM-PM, a resonant amplitude modulator (EOM-AM) operating at 5 is used to provide a dedicated frequency for measuring axion-induced amplitude changes. The signal is demodulated at this frequency using a local oscillator and the same low-pass filter as used for the phase lock. This frequency choice ensures that the phase-lock system does not compensate for amplitude changes caused by photon-to-axion conversion.

The laser beam is then split at a 50:50 beam splitter (BS) into a reference and a sensing arm. The sensing arm contains a 1

-long HC-PCF with a core radius of

μm, made at MPI, Erlangen, Germany [

21] (see

Figure 1). Free-space coupling into the HC-PCF is achieved with a stable efficiency of about

, marking the first milestone that can be further improved with optimized mode matching.

The fiber will be mounted in a custom-made aluminum holder with a production accuracy of approximately 20 μm, ensuring that it remains straight so that the full conversion length contributes to the measurement. A half-wave plate (HWP) positioned after the HC-PCF fine-tunes the output polarization, ensuring optimal alignment and thereby minimizing the modulation effort required from the broadband EOM.

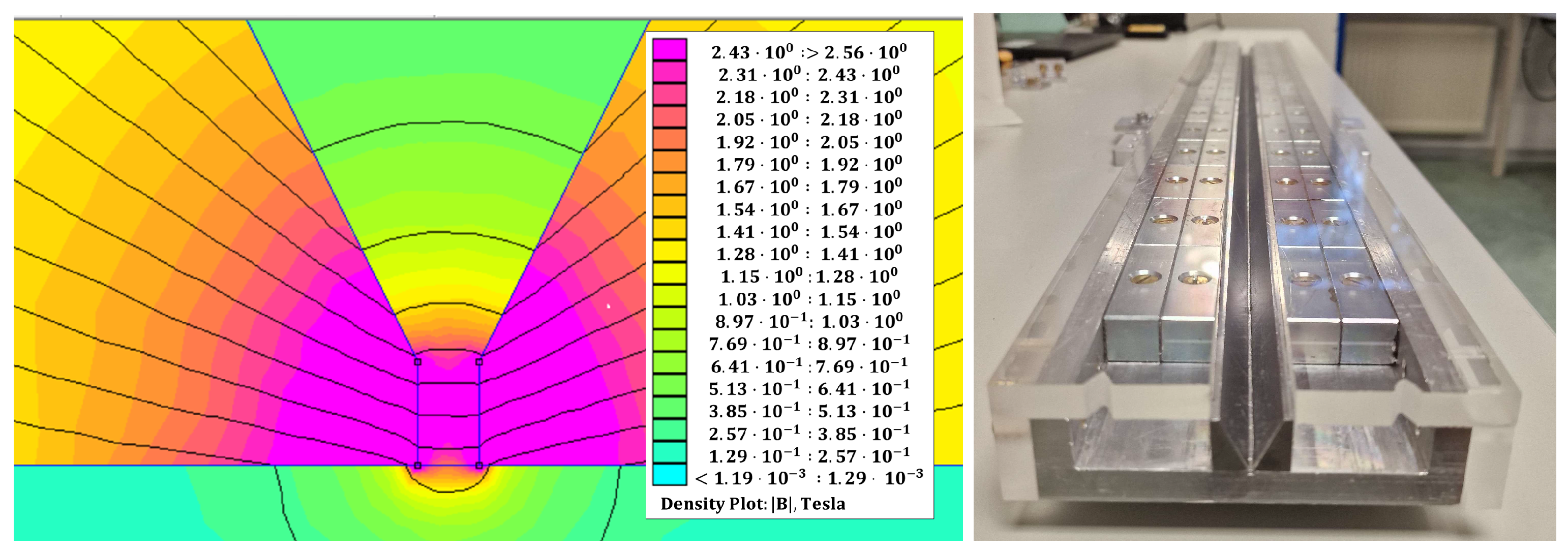

Photon–axion conversion occurs in an external magnetic field generated by a custom array of 60 Nd permanent magnets. To increase the magnetic flux density in the region of the fiber, a removable thin Fe wedge is positioned between the two magnet arrays, creating a

gap through which the HC-PCF is threaded (see

Figure 3 right). Finite-element simulations of the magnetic field in this region are shown in

Figure 3 left, and indicate a field of approximately 2

at the location of the HC-PCF. Replacing the Fe wedge with a Co-Fe alloy could further increase the field up to

. The magnet assembly is mounted on a motorized stage that vertically moves the magnet panel, positioning it under the HC-PCF for the

state or retracting it away for the

state. This allows direct comparison of measurements with and without the magnetic field for identification of axion-induced amplitude modulation.

After recombination at a second 50:50 BS, the output dark-port signal in PD1 is used to measure axion-induced amplitude changes, while the output bright-port (PD2) monitors the overall interferometer performance.

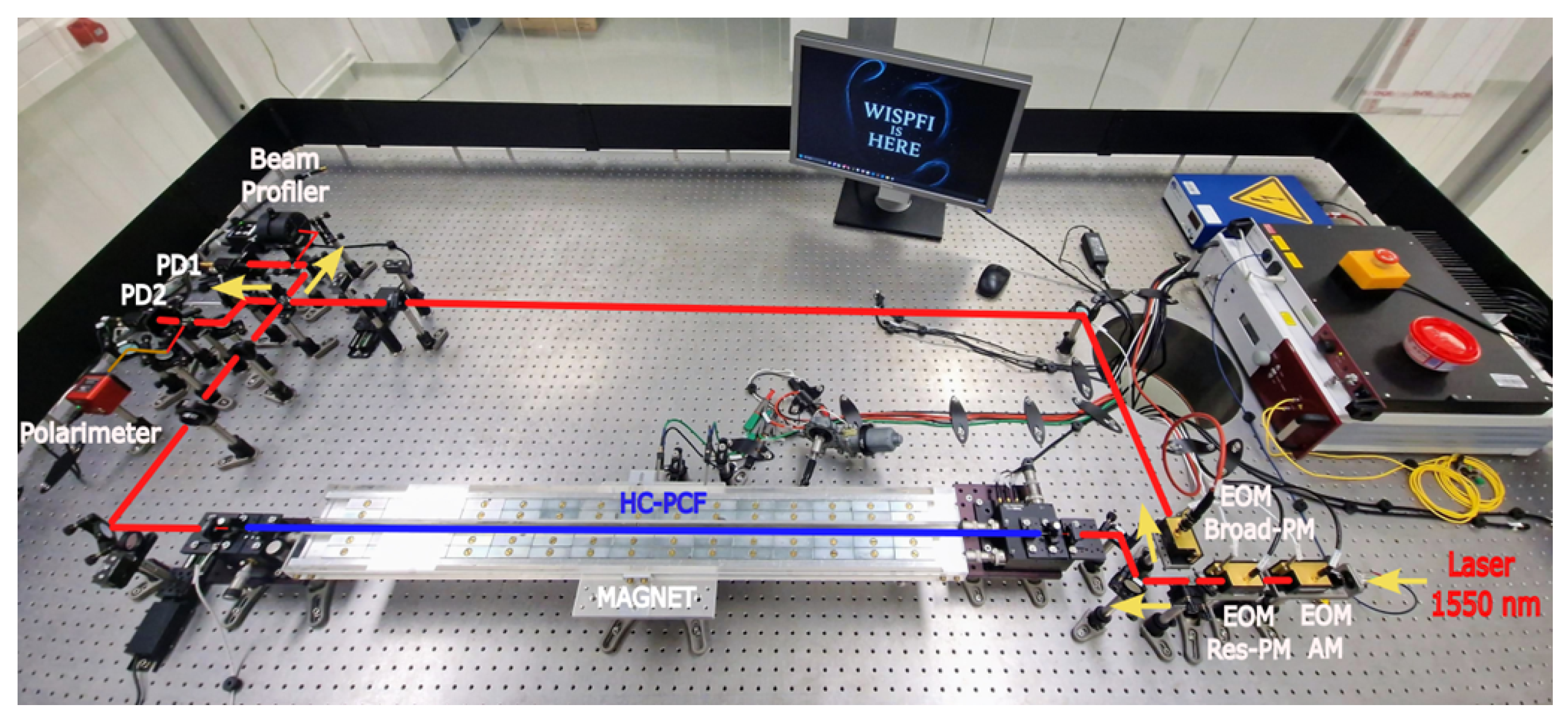

Finally, a fully automated Python-based (3.12) data acquisition (DAQ) system has been designed that monitors multiple system parameters, including polarization, beam profile, laser power, laser wavelength, temperature, and humidity. These measurements will provide the quality criteria for the analysis, ensuring stable conditions and reproducible measurements throughout the experiment. A photograph of the current laboratory implementation of the WISPFI prototype is shown in

Figure 4.

5. Projected Sensitivity

The sensitivity of the WISPFI prototype is evaluated assuming operation near a dark fringe, where the interferometer converts small axion-induced photon losses into measurable amplitude modulations. In this regime, the main noise sources are the dark current of the photodiode at the output dark-port (PD1) and the laser SN.

As described in

Section 4, the interferometer uses a high-power 2

, 1550

laser (NKT Photonics, Birkerød, Denmark) coupled with a 1

-long HC-PCF placed in a 2

magnetic field. Phase-locking of the interferometer is achieved near the dark fringe with a residual power of 1% at PD1. Under these conditions, the noise-equivalent power (NEP) contributions are

for SN and

for the InGaAs photodiode dark current. Hence, the dominant noise source in the measurement is the PD1 dark current.

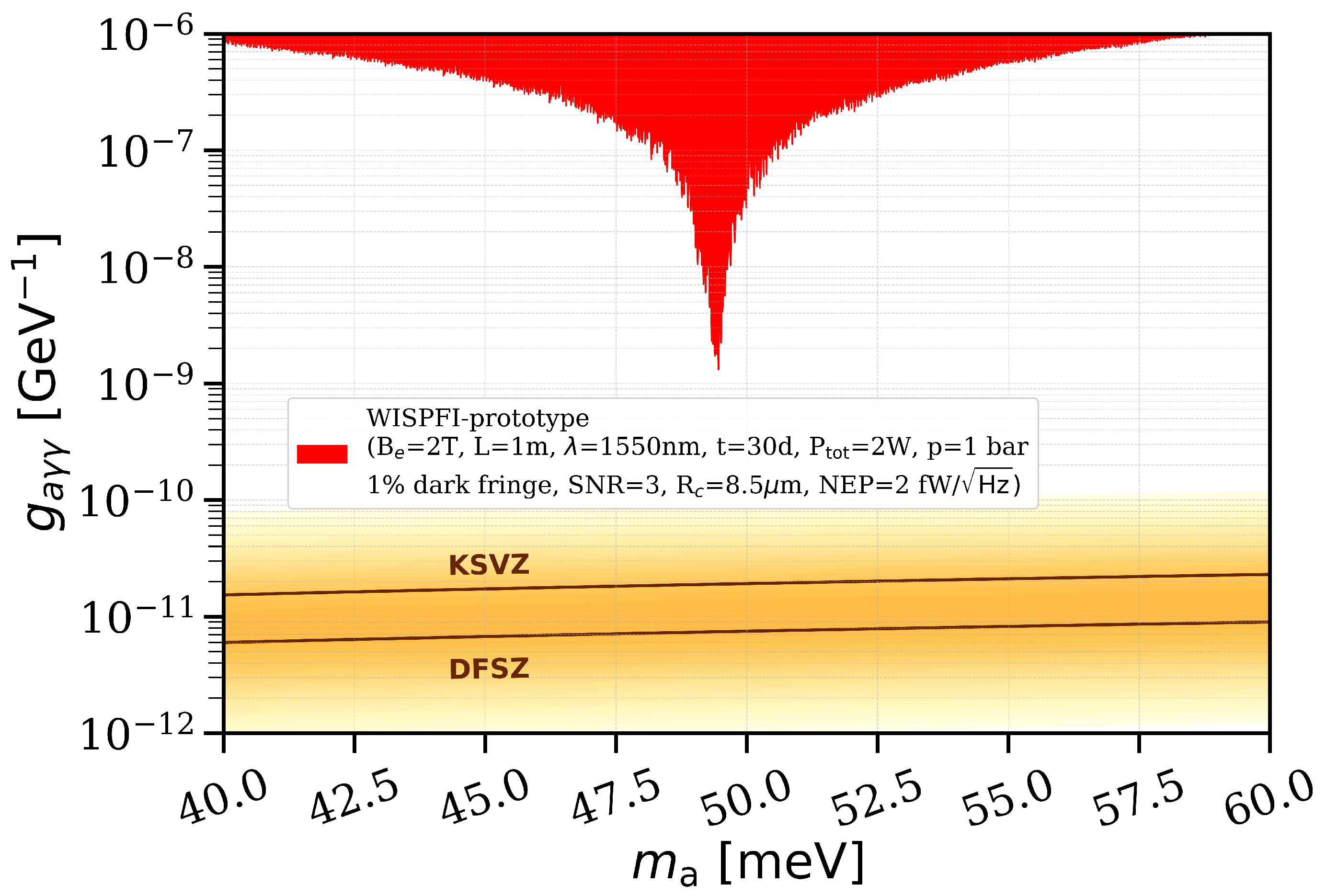

The expected sensitivity of the prototype allows probing an axion–photon coupling of

for an axion mass of

eV over a 30-day measurement period. This sensitivity can be expressed as follows:

Here, the phase modulation factor is defined as . For a modulation index , and , giving .

The HC-PCF is assumed to remain straight, with its electric field aligned to the magnetic field to maximize photon–axion conversion. The effective mode index of the propagating mode is computed assuming a constant temperature of 20 °C and a pressure of 1 bar along the 1

-long fiber. As discussed in

Section 2, the resonant axion mass (Equation (

5)) is primarily determined by the fiber core radius

(Equation (

6)).

The HC-PCF manufacturing process introduces small random variations in the core radius along the fiber, which can be characterized as low-frequency (

-like) fluctuations with typical length scales longer than the fiber segment. Larger variations in the core radius would broaden the accessible axion mass range while reducing the peak sensitivity. To account for these variations, we consider an average core radius

μm with a standard deviation

. For the sensitivity estimate, ten 1

-long fiber realizations are simulated, each divided into 100 segments of

, and the photon-to-axion conversion probability

is computed using a transfer-matrix approach [

22,

23].

Figure 5 shows the resulting median sensitivity of the WISPFI prototype.

6. Summary and Outlook

The WISPFI prototype represents the first table-top, DM-independent experiment capable of probing ALPs in a previously unexplored mass range around 50 meV. Using a HC-PCF in a phase-locked MZI, combined with a permanent Nd magnet array, the setup demonstrates the feasibility of detecting photon-ALP conversion in a compact interferometric platform. With the current configuration of 1 of HC-PCF, 2 magnetic field, and 2 laser power, the experiment is expected to probe an axion–photon coupling of over a measurement period of 30 days, providing a unique platform to explore this otherwise inaccessible parameter space. Phase-locking the interferometer near the dark fringe and using a dedicated amplitude modulation frequency ensures high-precision and reliable ALP signal detection.

Beyond the current prototype, several strategies have been identified to improve sensitivity and expand the mass coverage. Implementing a controlled pressure-tuning procedure in the HC-PCF [

24,

25] would allow systematic scanning of the resonant axion mass by modifying the effective refractive index of the guided mode. Additionally, integrating a Fabry–Pérot cavity along the sensing arm could further enhance the effective conversion length and optical power. Such cavities with finesses exceeding 3000 have been demonstrated using Pound–Drever–Hall locking, providing a practical route to boost the signal [

26,

27,

28].

Overall, the prototype validates the core experimental principles of the WISPFI concept and provides a versatile test-bench for the full-scale experiment. The combination of strong magnetic fields, precise phase and amplitude modulation, and automated data acquisition establishes a robust, scalable, and model-independent platform to explore previously inaccessible ALP parameter space.