Yield Stability of Selected Potato Cultivars Under Mulch and Fungicide Applications Across Different Environments †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. AMMI Analysis of Variance for Tuber Yield

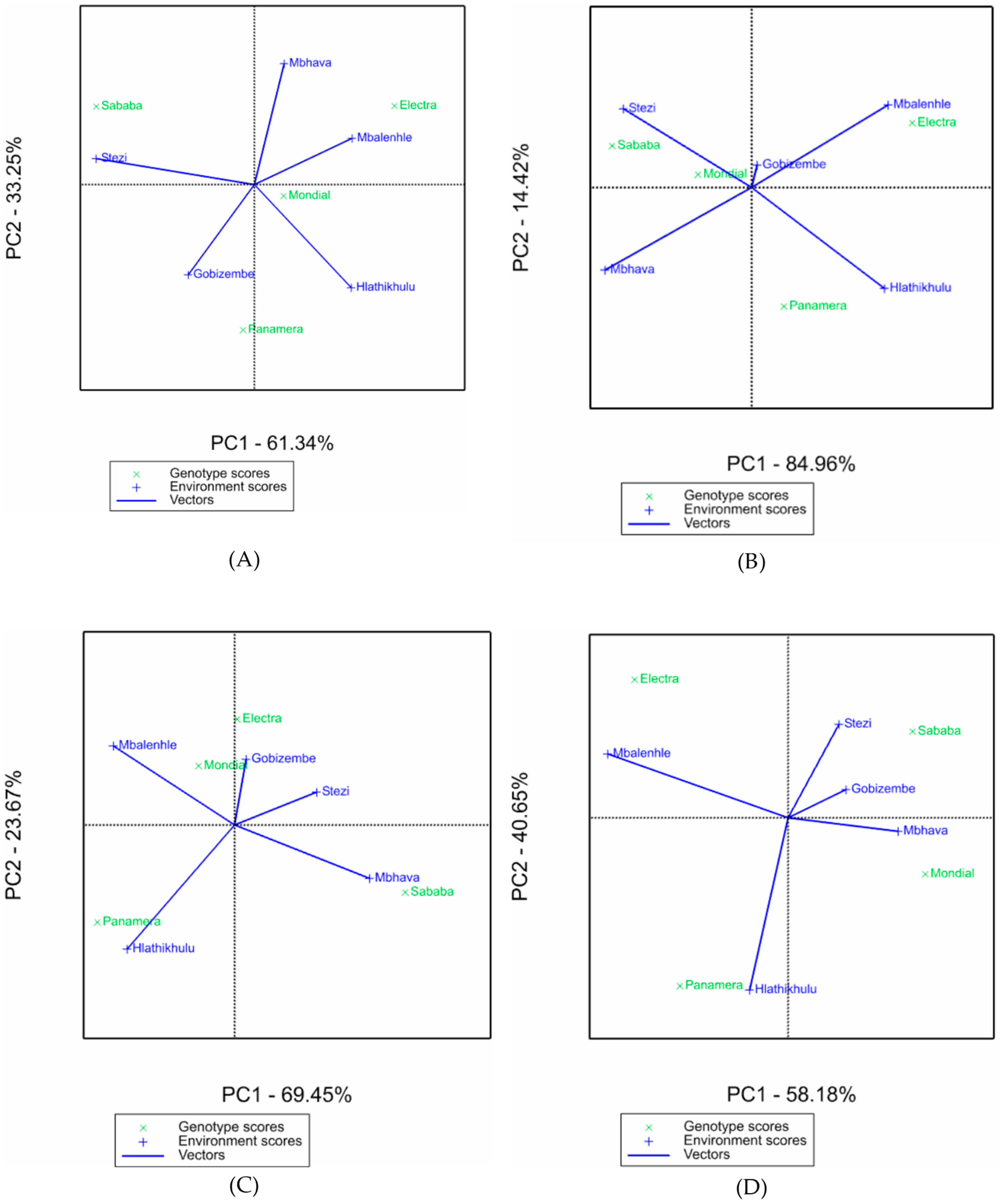

3.2. Genotype Tuber Yield Stability and Adaptive Analysis Using AMMI Biplot

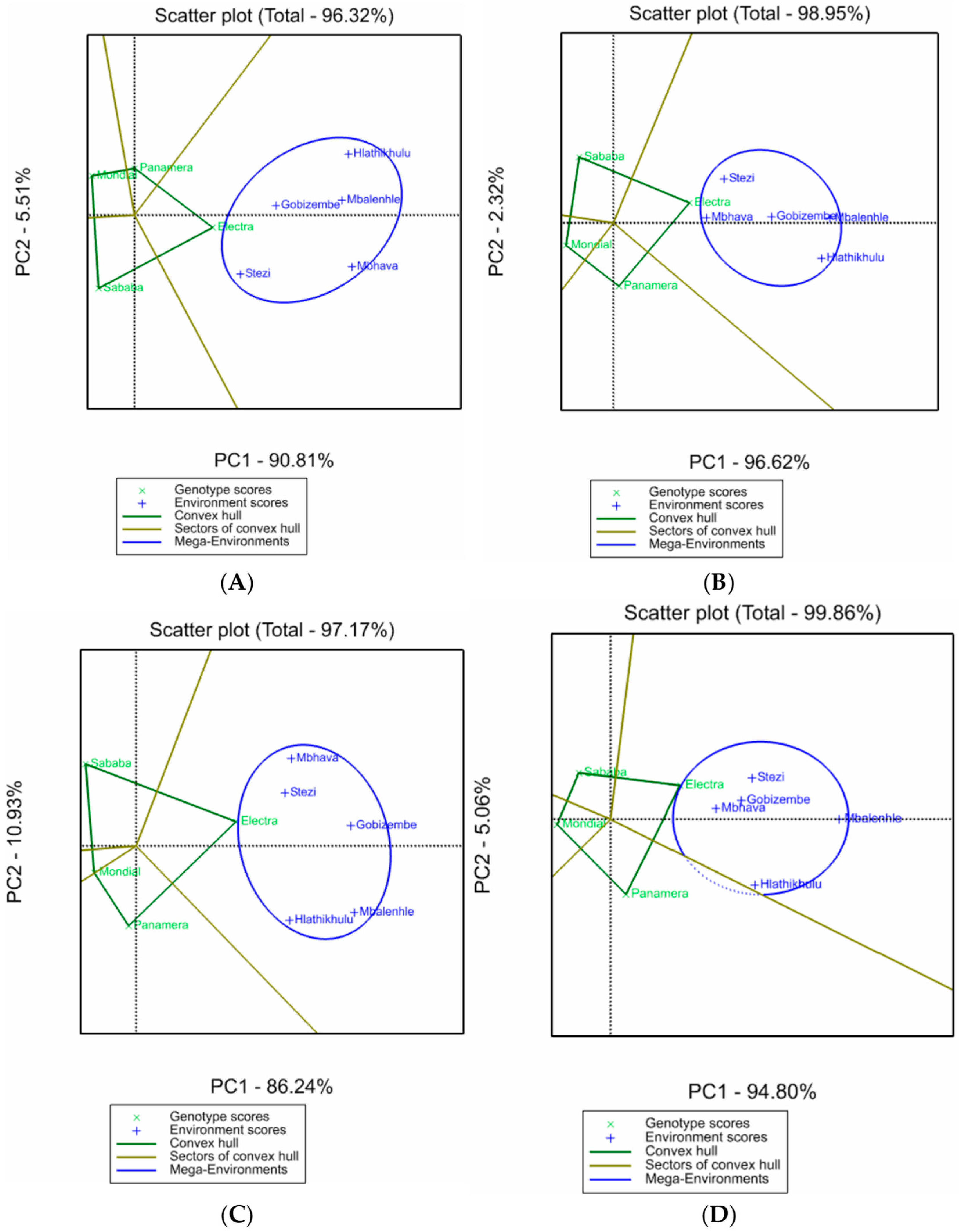

3.3. GGE Analyses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phungula, N.P.M.; Hadebe, S.T.; Schilte-Geldermann, E.; Sithole, L.; Ngobese, N.Z. Yield and growth response of selected potato cultivars to different mulch and fungicide applications, and various localities under rainfed conditions. Potato Res. 2024, 68, 2261–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puma-Cahua, J.; Belizario, G.; Laqui, W.; Alfaro, R.; Huaquisto, E.; Calizaya, E. Evaluating the yields of rainfed potato crop under climate change scenarios using the AquaCrop model in the Peruvian Altiplano. Sustainability 2024, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, Q.; Lei, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Qi, Y. Environmental factors influence the responsiveness of potato tuber yield to growing season precipitation. Crop Environ. 2024, 3, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phungula, N.P.M.; Hadebe, S.T.; Schilte-Geldermann, E.; Sithole, L.; Ngobese, N.Z. The response of potato late blight to the integration of selected potato cultivars, fungicides and mulch at different levels, and localities. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2025, 172, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karina, T.; Supit, I.; Groot, A.; Ludwig, F.; Demissie, T. Projected climate change impacts on potato yield in East Africa. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 166, 127560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Feria, R.A.; Basso, B. Unstable crop yields reveal opportunities for site-specific adaptations to climate variability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y. Reduced crop yield stability is more likely to be associated with heat than with moisture extremes in the US Midwest. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G.; Lerna, A. Dissecting the genotype x environment interaction for potato tuber yield and components. Agronomy 2022, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyew, M.; Feyissa, T.; Geleta, M.; Tesfaye, K.; Hammenhag, C.; Carlsson, A.S. Genotype by environment interaction, correlation, AMMI, GGE biplot and cluster analysis for grain yield and other agronomic traits in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench). Plus One 2021, 16, e0258211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanpanah, D.; Azimi, J. Yield stability analysis of potato cultivars in spring cultivation and after barley harvest cultivation. Am.-Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci 2010, 9, 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Daemo, B.B.; Ashango, Z. Application of AMMI and GGE biplot for genotype by environment interaction and yield stability analysis in potato genotypes grown in Dawuro zone, Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.; Mekbib, F.; Gashaw, A. AMMI and GGE biplot analysis of grain yield of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes at moisture deficit environment of Wollo, Ethiopia. J. Agric. Sci. Pract. 2019, 4, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilate, D.B.; Belew, Y.D.; Mulualem, B.T.; Gebreselassie, A.W. AMMI and GGE biplot analyses for mega environment identification and selection of some high-yielding cassava genotypes for multiple environments. Int. J. Agron. 2023, 1, 6759698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadersa, Y.; Santchurn, D.; Soulange, J.G.; Saumtally, S.; Parmessur, Y. Genotype by environment interaction for marketable tuber yield in advanced potato clones using AMMI and GGE methods. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2022, 30, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Bhardwaj, V.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, V.K. BLUP and stability analysis of multi-environment trials of potato varieties in sub-tropical Indian conditions. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemechu, G.E.; Mulualem, T.; Semman, N. Genotype by environment interaction effect on some selected traits of orange-fleshed sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Heliyon 2022, 8, e12395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Appelsbosch | Swayimane | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mbalenhle | Hlathikhulu | Gobizembe | Mbhava | Stezi | |

| Altitude (m.a.s.l) | 1003 | 922 | 940 | 750 | 874 |

| Latitude | 30°52′4.84″ E | 30°52′14.62″ E | 30°37′55.25″ E | 30°39′44.64″ E | 30°35′24.42″ E |

| Longitude | 29°22′33.88″ S | 29°23′53.58″ S | 29°29′22.98″ S | 29°33′54.98″ S | 29°31′51.10″ S |

| Annual rainfall (mm) | 540.3–774.0 | 540.3–778 | 616–690.8 | 602.7–623.4 | 629.3–663.7 |

| Day air temperature (min–max) (°C) | 5.8–38.7 | 4.6–36.4 | 4.9–37.7 | 5.6–37.4 | 4.5–36.6 |

| Soil type | Umbrisols | Umbrisols | Ferralsols | Ferralsols | Umbrisols |

| Source of Variation | DF | SS | MS | % SS Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-mulched sprayed | ||||

| Total | 179 | 26,972 | 150.7 | |

| Treatments | 19 | 11,447 | 602,5 | |

| Genotype | 3 | 6368.13 | 2122.7 * | 55.63 |

| Environment | 4 | 3992.78 | 998.2 * | 34.88 |

| Block | 10 | 280 | 28 | |

| Interactions | 12 | 1086 | 90.5 ns | 9.487 |

| Residuals | 2 | 59 | 29.4 | |

| Errors | 150 | 15,245 | 101.6 | |

| Mulched unsprayed | ||||

| Total | 179 | 27,701 | 154.8 | |

| Treatments | 19 | 11,915 | 627.1 | |

| Genotype | 3 | 7223 | 2407.8 * | 60.62 |

| Environment | 4 | 3688 | 922.1 * | 30.95 |

| Block | 10 | 414 | 41.4 | |

| Interactions | 12 | 1003 | 83.6 ns | 8.42 |

| Residuals | 2 | 15 | 7.3 | |

| Errors | 150 | 15,372 | 102.5 | |

| Mulched sprayed | ||||

| Total | 179 | 28,572 | 159.6 | |

| Treatments | 19 | 13,181 | 693.7 | |

| Genotype | 3 | 7454 | 2484.6 * | 56.55 |

| Environment | 4 | 4276 | 1069.1 * | 32.44 |

| Block | 10 | 918 | 91.8 | |

| Interactions | 12 | 1451 | 120.9 ns | 11.01 |

| Residuals | 2 | 100 | 49.9 | |

| Errors | 150 | 14,474 | 96.5 | |

| Non-mulched unsprayed | ||||

| Total | 179 | 31,444 | 175.7 | |

| Treatments | 19 | 14,490 | 762.6 | |

| Genotype | 3 | 10,132 | 3377.2 * | 69.924 |

| Environment | 4 | 2974 | 743.4 * | 20.52 |

| Block | 10 | 432 | 43.2 | |

| Interactions | 12 | 1385 | 115.4 ns | 9.56 |

| Residuals | 2 | 9 | 4.3 | |

| Errors | 150 | 16,522 | 110.1 |

| Cultivar | Tuber Yield (t ha−1) | Rank | ASV | IPCA1 | IPCA2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-mulched × sprayed | |||||

| Electra | 51.13 | 3 | 3.71 | 1.92 | 1.08 |

| Mondial | 35.84 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.4 | −0.16 |

| Panamera | 41.71 | 2 | 2.02 | −0.16 | −1.99 |

| Sababa | 37.41 | 4 | 4.15 | −2.17 | 1.07 |

| Non-mulched × unsprayed | |||||

| Electra | 46.01 | 4 | 14.47 | 2.45 | 0.98 |

| Mondial | 26.39 | 2 | 4.81 | −0.82 | 0.19 |

| Panamera | 34.89 | 1 | 3.43 | 0.49 | −1.82 |

| Sababa | 29.27 | 3 | 12.55 | −2.13 | 0.64 |

| Mulched × sprayed | |||||

| Electra | 52.29 | 1 | 1.56 | −0.04 | 1.55 |

| Mondial | 36.79 | 2 | 1.76 | −0.53 | 0.87 |

| Panamera | 40.64 | 3 | 6.07 | −2.01 | −1.42 |

| Sababa | 36.37 | 4 | 7.41 | 2.50 | 0.99 |

| Mulched × unsprayed | |||||

| Electra | 43.09 | 4 | 2.78 | −1.65 | 1.48 |

| Mondial | 26.45 | 2 | 2.19 | 1.47 | −0.61 |

| Panamera | 35.67 | 3 | 2.45 | −1.16 | −1.81 |

| Sababa | 29.42 | 1 | 2.12 | 1.34 | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Phungula, N.P.M.; Hadebe, S.T.; Sithole, L.; Nadioo, M.; Ngobese, N.Z. Yield Stability of Selected Potato Cultivars Under Mulch and Fungicide Applications Across Different Environments. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2025, 54, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025054006

Phungula NPM, Hadebe ST, Sithole L, Nadioo M, Ngobese NZ. Yield Stability of Selected Potato Cultivars Under Mulch and Fungicide Applications Across Different Environments. Biology and Life Sciences Forum. 2025; 54(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025054006

Chicago/Turabian StylePhungula, Nosipho Precious Minenhle, Sandile Thamsanqa Hadebe, Lucky Sithole, Morgan Nadioo, and Nomali Ziphorah Ngobese. 2025. "Yield Stability of Selected Potato Cultivars Under Mulch and Fungicide Applications Across Different Environments" Biology and Life Sciences Forum 54, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025054006

APA StylePhungula, N. P. M., Hadebe, S. T., Sithole, L., Nadioo, M., & Ngobese, N. Z. (2025). Yield Stability of Selected Potato Cultivars Under Mulch and Fungicide Applications Across Different Environments. Biology and Life Sciences Forum, 54(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025054006