1. Introduction

In 21st-century educational contexts, proficiency in the English language has evolved from being an additional skill to becoming a central pillar of students’ academic and professional training. Self-perceived competence in English learning is defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform tasks involving the use of English, including listening, speaking, reading, and writing (

Kim et al., 2015). This perception is closely tied to the construct of self-efficacy, as proposed by Bandura, which posits that beliefs about one’s own capabilities influence motivation, choice of learning strategies, and academic performance (

Bandura, 1997). High levels of English self-efficacy can therefore facilitate foreign language acquisition by fostering positive attitudes toward language learning, increasing tolerance for mistakes, and strengthening commitment to cognitively demanding tasks (

Anam & Stracke, 2019). Although perceived competence does not always align with actual ability, it directly influences the effort invested, persistence in the face of errors, and willingness to take communicative risks (

Mandić et al., 2024).

Studies conducted with secondary and university students have consistently shown that higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with better performance on language proficiency tests and greater participation in class (

Dong et al., 2022). This relationship is well supported in the literature, which reports positive correlations between English self-efficacy and overall perceived competence in language learning (

Kim et al., 2015). Furthermore, self-perceived competence is particularly relevant in language acquisition, where self-confidence has been identified as a critical factor for academic success (

Raoofi et al., 2012). Several studies have found that in certain school environments, speaking English with a marked pronunciation may become a target of peer ridicule, creating insecurity and reluctance to engage in oral activities, particularly during adolescence (

Busse, 2017).

One of the phenomena that significantly interferes with students’ academic development is bullying and its digital counterpart, cyberbullying. Numerous studies have shown that students who experience bullying or cyberbullying tend to exhibit lower academic performance, higher dropout rates, and weaker engagement with the school environment (

Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020). These experiences are also associated with diminished self-esteem, reduced self-perceived competence, and lower motivation for learning (

Raoofi et al., 2012). This combination of factors can be particularly detrimental to the development of foreign language skills, which demand high levels of communicative exposure and substantial confidence in one’s abilities (

Mandić et al., 2024). However, the impact of bullying on language learning has received limited attention in the literature. It has been shown that adolescents who suffer from high levels of social anxiety due to school bullying tend to avoid communicative situations in English, which in turn reduces their oral practice and overall performance (

Wu et al., 2021). This negative social pressure may act as an additional risk factor, intensifying the effects of bullying or cyberbullying and contributing to a vicious cycle in which avoidance of linguistic exposure limits actual learning opportunities and reinforces low self-perceived language competence (

Carrie, 2017).

In Spain, English has been institutionalized as a compulsory subject from primary through upper secondary education and serves as a key criterion for access to mobility programs and higher education (

Reichelt, 2006). Nevertheless, recent studies have reported that English proficiency among outcomes Spanish adolescents remains low compared to other European countries, ranking in the lower-middle range of language proficiency indices (

Llurda & Mocanu, 2024). This underperformance cannot be explained solely by curricular factors but also reflects psychosocial variables such as motivation, school climate, and students’ personal experiences (

Cedzich, 2024). Although the development of spoken English competence is multifactorial, it is also hindered by socially unfavorable attitudes (

Llurda & Mocanu, 2024). In recent years, concern over school bullying has grown in Spain due to its high prevalence. According to recent data, between 30 and 40 percent of secondary school students have been involved in bullying situations, whether as victims, aggressors, or witnesses (

González-Cabrera et al., 2020). Regarding cyberbullying, studies indicate that between 15 and 20 percent of Spanish adolescents have been victims at some point, with higher incidence reported in later years of secondary education (

Calmaestra et al., 2020).

Expanding on these considerations, recent studies carried out in both developed and developing countries suggest that girls tend to exhibit higher levels of self-efficacy in language-related tasks (

Huang, 2013). In contrast, boys are generally more prone to engaging in bullying behaviors and tend to show poorer academic performance when involved in such behaviors, either as victims or as aggressors (

Obregón-Cuesta et al., 2022). Additionally, various individual and contextual factors may influence the relationship between bullying and language competence, making it essential to account for them as covariates in the analysis. Age, for example, has been shown to be closely linked to cognitive and emotional development, which can affect both linguistic ability and how students perceive and respond to bullying situations (

Jansen & Kiefer, 2020). Maternal education level has also been associated with key indicators of child and adolescent development, including academic achievement, school motivation, and language aspirations (

Baharvand et al., 2021). Finally, body mass index (BMI) and weekly physical activity levels have been identified as relevant predictors of psychological well-being, influencing self-perception, motivation for learning, and overall school adjustment (

Bacon & Lord, 2021).

The extent to which current experiences of bullying and cyberbullying are associated with adolescents’ self-perceived competence in English as a foreign language remains largely unexplored. Moreover, few studies have simultaneously considered both victimization and perpetration dimensions, despite their potential to enhance understanding of the complexity of the phenomenon and inform more effective educational interventions. Based on these considerations, the aim of the present study was to examine the association between victimization and aggression, in both bullying and cyberbullying contexts, and perceived English language competence among boys and girls aged 10 to 16. In addition, the study sought to assess the level of risk posed by bullying and cyberbullying experiences, whether as victim or aggressor, in relation to lower perceived competence across the four core English skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). It was hypothesized that involvement in bullying or cyberbullying situations, either as a victim or as an aggressor, would be negatively associated with self-perceived English language competence among adolescents aged 10 to 16.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This cross-sectional quantitative study included a total of 444 Spanish children and adolescents (50.00% boys) enrolled in five educational centers located in the province of Jaén (Andalusia, Spain). Participants were between 10 and 16 years old (M = 13.27, SD = 1.64). A convenience sampling method was used to select the schools, comprising three located in urban areas (≥10,000 inhabitants) and two in rural areas (<10,000 inhabitants). Within each institution, random cluster sampling was applied at the classroom level to ensure balanced representation across schools. Participants’ biometric characteristics, physical activity levels, involvement in bullying, and English language competence are presented in

Table 1.

Analysis of participant characteristics revealed significant sex-based differences in several variables. Boys reported significantly higher levels of weekly physical activity (p < 0.001). Conversely, girls reported greater exposure to bullying victimization (p = 0.015). Additionally, girls outperformed boys in all dimensions of English language competence: listening, speaking, reading, and writing (all p < 0.003).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable: Self-Perceived English Competence

Self-perceived English competence was assessed through students’ self-perceived efficacy across four core language domains: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. For this purpose, the Questionnaire of English Self-Efficacy (QESE) was administered (

C. Wang et al., 2014). This self-report instrument consists of 32 items in which participants rate their ability to perform specific tasks in English using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“I cannot do it at all”) to 7 (“I can do it very well”). The items are organized into four subscales, each corresponding to one of the language skills: (1) Listening, (2) Speaking, (3) Reading, and (4) Writing.

Multiple studies have reported high internal consistency for the instrument, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.88 (for listening and reading) to 0.92 (for speaking), and an overall reliability of 0.97 (

C. Wang et al., 2014). The QESE’s psychometric properties have been validated across diverse cultural contexts, including China, South Korea, Germany, and the United States, demonstrating factorial and construct validity in all applications (

C. Wang et al., 2014). Since a validated version for the Spanish context was not available, the translation was conducted by a bilingual expert using a standard back-translation method to ensure linguistic and cultural equivalence. In the present study, the instrument demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of α = 0.934 for listening, α = 0.949 for speaking, α = 0.933 for reading, and α = 0.945 for writing. Although these reliability values are high, they remain below the threshold (α > 0.95) commonly associated with potential item redundancy. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as evidence of strong internal consistency rather than full construct validity in the Spanish context.

2.2.2. Predictor/Independent Variables: Bullying and Cyberbullying

Bullying was evaluated using the Spanish adaptation of the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (EBIP-Q), whose validation was carried out by Ortega-Ruiz and colleagues (

Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2016). This tool includes 14 items aimed at capturing two dimensions: experiences of victimization (e.g., “I have been deliberately pushed or hit by other students”) and perpetration (e.g., “I have verbally insulted a peer to hurt their feelings”). Prior research (

Solas-Martínez et al., 2025) has shown that both subscales demonstrate solid internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.83 for victimization and 0.79 for aggression.

To assess cyberbullying, the study employed the Spanish version of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIP-Q;

Del Rey et al., 2015), which comprises 22 items and distinguishes between cybervictimization (e.g., “Offensive messages about me have been posted online”) and cyberaggression (e.g., “I have shared harmful rumors about a peer through social networks”). The internal reliability of both subscales is also adequate, with α = 0.87 for cybervictimization and α = 0.82 for cyberaggression. Both questionnaires apply a bidimensional model, focusing on both the victim and aggressor roles, and responses are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = more than once a week). Lower scores suggest minimal or no participation in bullying dynamics, whereas higher scores denote frequent involvement in such actions.

To ensure that the behaviors assessed corresponded to actual bullying and not to isolated incidents or occasional conflicts, both questionnaires included key indicators such as repetition over time and power imbalance. Items were framed within the context of the previous two months, allowing for the identification of recurrent patterns.

The questionnaires were completed individually and anonymously, with an approximate duration of 15 min. To minimize potential response bias, behaviors were described without using the terms “bullying” or “cyberbullying,” and items were not read aloud to the group. This strategy was intended to create a more comfortable environment for participants and to reduce the likelihood of socially desirable responding or fear of retaliation (

Runze & van IJzendoorn, 2023).

2.2.3. Confounding Variables

Participants’ age and their mothers’ educational attainment were collected through a sociodemographic questionnaire. Age was considered a potential confounding factor, given that previous studies have highlighted its influence on cognitive and emotional development, both of which are essential for learning processes and school adaptation (

El Zaatari & Maalouf, 2022). Similarly, maternal education level has been significantly associated with various indicators of child and adolescent development, including academic performance, mental health, and intelligence quotient (

Baharvand et al., 2021).

Body Mass Index (BMI) and the level of physical activity per week were incorporated as control variables, given their established links to both physical and psychological health, as well as their relevance to educational indicators such as academic achievement and learning motivation (

Bacon & Lord, 2021;

Seum et al., 2022). BMI was calculated using the Quetelet index, dividing body weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m

2). Measurements for height and weight were taken with a digital scale (ASIMED

®, Type B, Class III) and a portable stadiometer (SECA

® 214, SECA Ltd., Hamburg, Germany), with participants dressed in light clothing and barefoot.

The assessment of physical activity was based on the PACE+ Adolescent Physical Activity Measure (

Prochaska et al., 2001), which consists of two questions asking participants to indicate how many days they engaged in at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity during the past week and during a typical week. The final score was derived by averaging the two responses [(R1 + R2)/2], and the measure has demonstrated adequate reliability, with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79.

2.3. Procedure

Before initiating the data collection process, the research team provided detailed information about the study’s goals and methodology to parents, legal guardians, teachers, and school administrators. Informed consent in written form was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participating students. To guarantee confidentiality, each participant was identified with a numerical code, ensuring their anonymity throughout the stages of data handling and analysis.

The evaluation took place during regular school hours, in coordination with teaching staff at the participating schools. All assessments and questionnaires were administered in the students’ usual classrooms under the supervision of both the research team and the teachers responsible for each group. Instruments were completed individually and anonymously. The variables measured included: English language self-efficacy, levels of victimization and aggression in bullying and cyberbullying contexts, BMI, weekly physical activity level, age, and maternal education level. Anthropometric measurements were conducted directly by the research team using certified equipment (digital scale and portable stadiometer), while sociodemographic and psychological variables were collected via standardized questionnaires.

The study received ethical clearance from the by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Jaén (Spain; protocol code NOV.22/2.PRY, approved in November 2022). Its methodological framework adheres to current Spanish regulations governing biomedical research involving human participants (Law 14/2007, dated July 3), as well as to the stipulations of the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights. In addition, all research procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision, Brazil).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

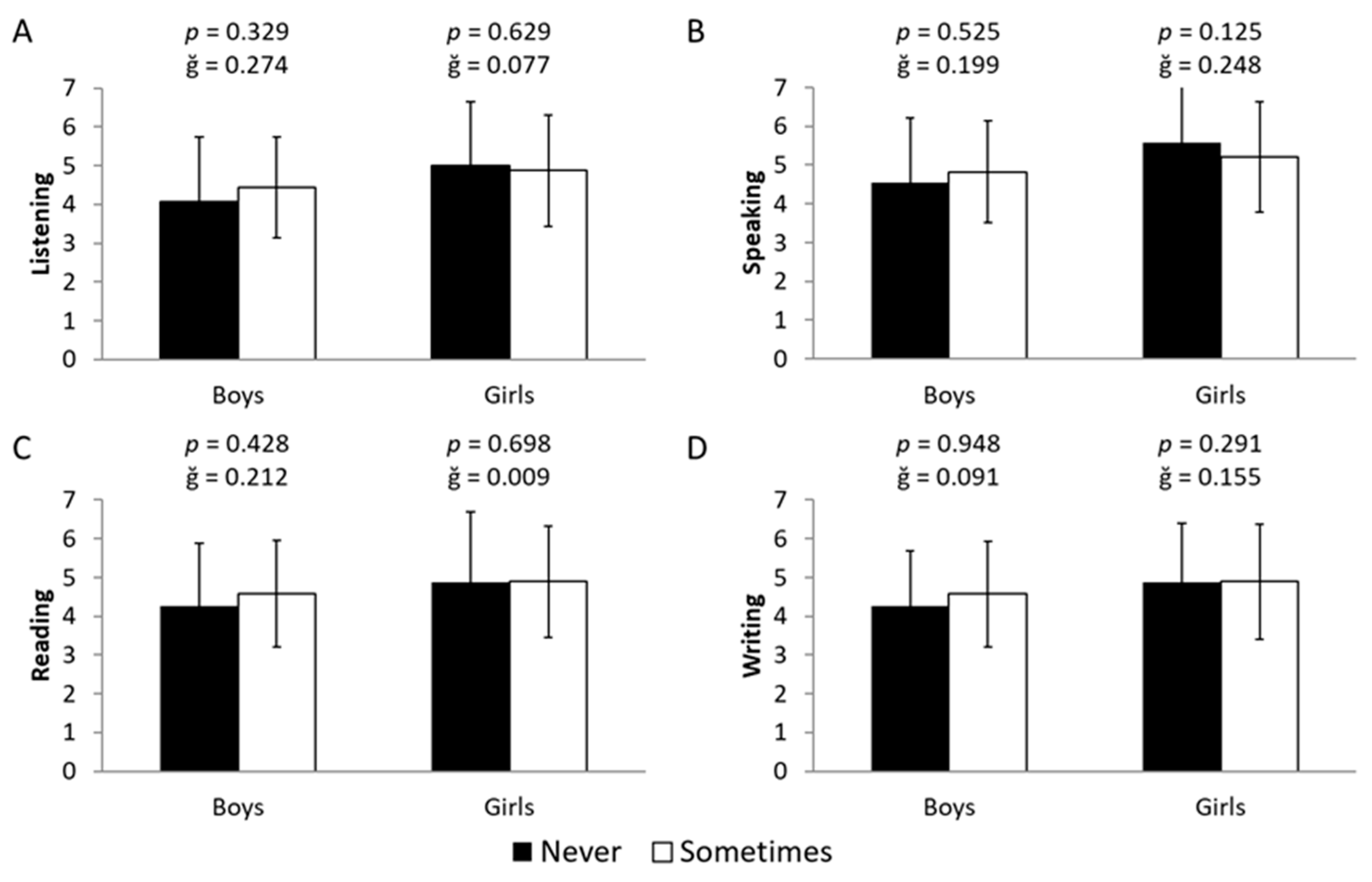

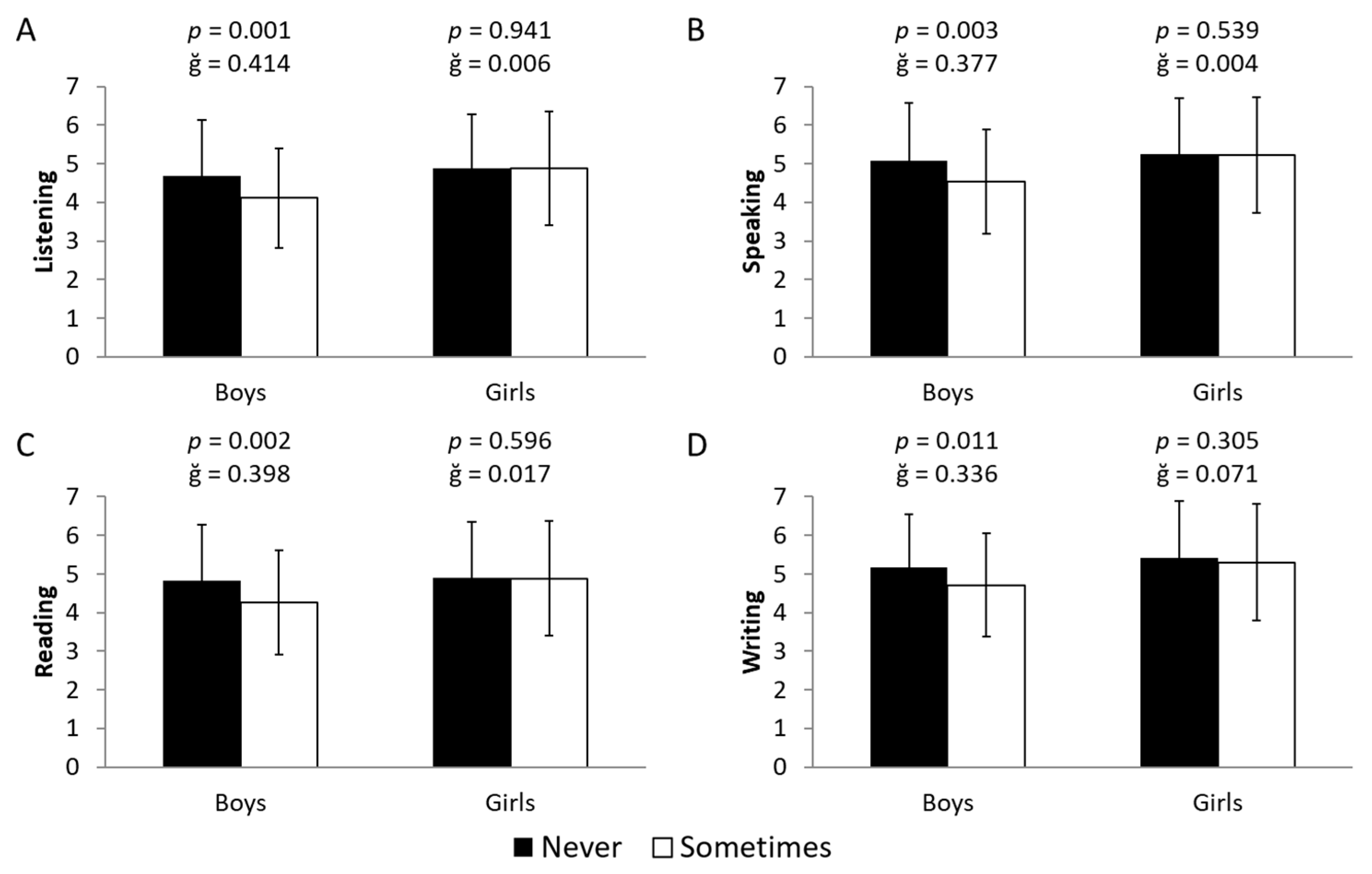

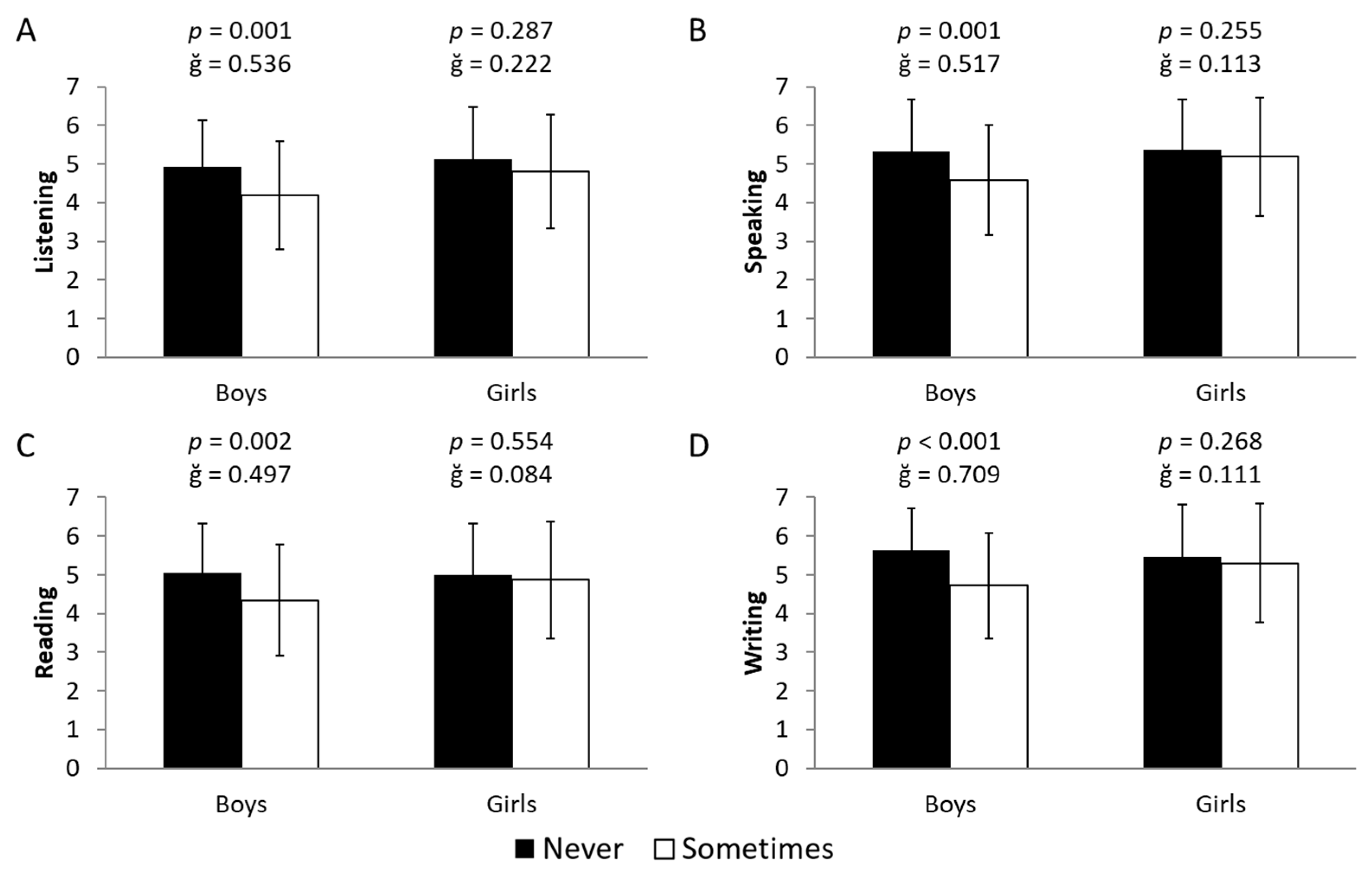

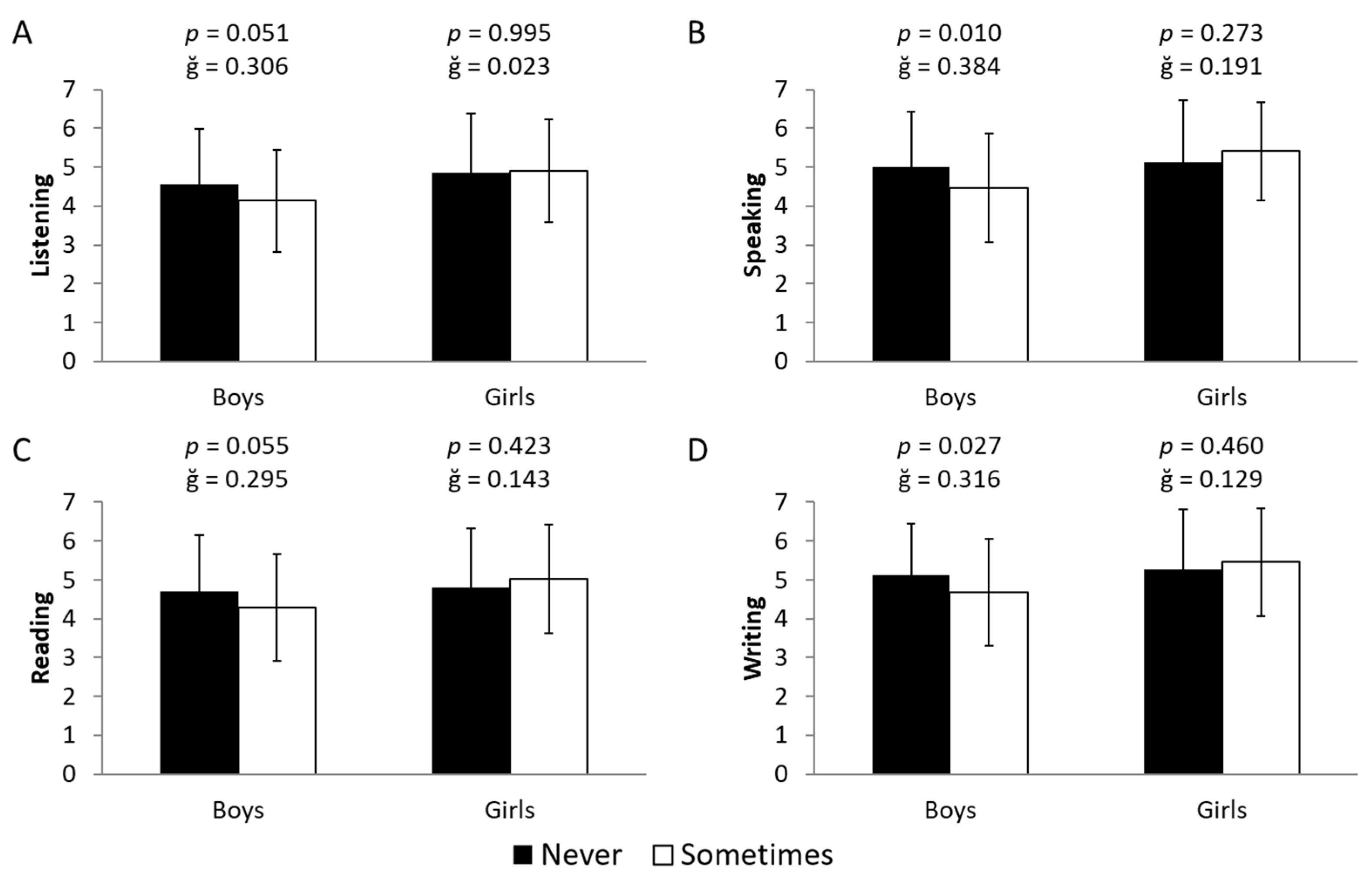

To compare continuous and categorical variables between male and female participants, Student’s t-tests and chi-square (χ2) tests were employed, respectively. Prior to these analyses, the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variances were assessed through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene tests. In order to determine whether adolescents with no history of involvement—either as victims or aggressors—in conventional bullying or cyberbullying exhibited higher self-perceived proficiency in English, analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were performed. In each of these analyses, the self-perceived English competence subscales (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) served as dependent variables. The independent variables (fixed factors) included bullying victimization and aggression, as well as cybervictimization and cyberaggression.

For the purposes of analysis, bullying and cyberbullying variables were dichotomized: participants who reported never being victims or aggressors (score = 1 on the questionnaire) were categorized as the “Never” group, while those who reported experiencing at least one instance of victimization or aggression (score > 1) were placed in the “Sometimes” group. Given unequal group sizes in some comparisons, effect sizes were calculated using Hedges’

g, with values of 0.20 considered small, 0.50 medium, and 0.80 large (

Martínez-López et al., 2018). Additionally, percentage differences between groups were calculated using the formula: [(Large-measurement − Small-measurement)/Small-measurement] × 100.

To estimate the risk associated with bullying and cyberbullying victimization or aggression in the development of lower English language competence, binary logistic regression analyses were performed. For this, the dependent variables (the four English proficiency subscales) were dichotomized using the median as a cutoff point (

Dichev & Dicheva, 2017;

Lepinet et al., 2023). Participants were classified into two groups based on their scores in each language skill: those scoring at or above the median were considered to have high competence (serving as the reference group), while those scoring below the median were categorized as having low competence (risk group).

All statistical models controlled for the following covariates: age, body mass index (BMI), maternal educational attainment, and weekly physical activity. Regarding the control variables, Age, BMI, and physical activity were entered as continuous variables, while maternal education level was treated as a categorical covariate. As for missing data, a listwise deletion procedure was applied. Therefore, questionnaires with incomplete information on the study variables were excluded, resulting in a final analytical sample of 444 participants with complete data. Analyses were stratified by sex and conducted with a 95% confidence interval, considering results significant at p < 0.05. All statistical procedures were carried out using SPSS software, version 25.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the relationship between involvement in bullying and cyberbullying and self-perceived English language competence among adolescents aged 10 to 16. Boys who had experienced cybervictimization reported lower levels of competence in listening, speaking, reading, and writing, and were between four and six times more likely to fall into the low self-efficacy category for these skills. Likewise, boys who had engaged in bullying aggression scored significantly lower across all linguistic domains. Those involved in cyberaggression also exhibited lower perceived competence in speaking and writing, with an elevated risk of low self-efficacy scores in reading and writing. Among girls, cybervictimization was associated with an increased risk of low self-perceived competence in all four English language skills, with particularly pronounced effects in speaking and listening. Furthermore, girls involved in cyberaggression were significantly more likely to show low self-efficacy across all English subskills, with up to an approximately elevenfold increase in the risk of low perceived competence in listening and more than double the risk in speaking and writing.

Our findings confirm that adolescents who are victims of cyberbullying tend to demonstrate lower competence across all English language skills, with boys showing particular vulnerability. This association may be explained by specific features of cyberbullying, such as its persistence over time, the anonymity of the aggressor, and the public nature of the exposure, which generate a continuous sense of emotional threat that is difficult to manage in the school context (

Kowalski & Limber, 2013). Previous studies have shown that cyberbullying is linked to elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal, which directly affect academic self-efficacy and active classroom participation (

Bussey et al., 2020). In the specific context of language learning, these consequences can be particularly harmful, as linguistic skills, especially speaking and writing, require high levels of communicative exposure and confidence in one’s abilities (

Delgado et al., 2019). Avoidance of these situations out of fear of judgment or ridicule, which is common among cyberbullying victims, may significantly limit real learning opportunities (

Bussey et al., 2020). Moreover, recent research indicates that experiences of digital victimization are more strongly associated with reduced academic self-efficacy than traditional bullying, due to the broader emotional and social reach of online harassment (

Bussey et al., 2020).

One of the most noteworthy findings of this study was the observation that boys exhibited broader and more consistent impairments in their self-perceived language competence when involved in bullying situations, both as victims and aggressors. This generalized vulnerability may be linked to lower baseline levels of academic self-efficacy and to the use of less adaptive coping strategies (

Liu et al., 2023). Previous research has shown that boys tend to externalize emotional distress through disruptive behaviors, academic withdrawal, or rejection of the school environment, particularly when they perceive difficulties in areas such as language learning (

Evans et al., 2019). This behavioral expression of distress may not only limit active participation in language-related tasks, but also reinforce a downward spiral of demotivation and poor performance (

Varela et al., 2021).

Notably, the girls in the present study displayed a more specific pattern of impairment, with significant negative effects primarily observed in cases of cyberaggression. Generally, girls tend to report higher levels of self-efficacy in language-related tasks, which may explain why not all are equally affected when exposed to bullying situations (

Huang, 2013). This self-efficacy may function as a protective factor that buffers the impact of moderate negative experiences, promoting greater persistence and confidence in the face of academic challenges (

Huang, 2013). However, this advantage appears to deteriorate when girls actively engage in aggressive behaviors (

Kutuk et al., 2022). Furthermore, exposure to digital hostility can pose a direct threat to both personal and social identity, particularly during adolescence, a developmental stage in which self-concept is highly sensitive to peer perception (

Kutuk et al., 2022). In this context, girls involved in cyberaggression have been found to experience a marked decline in communicative confidence and self-perceived linguistic ability, likely due to the dissonance between their aggressive role and internalized prosocial values, as well as increased exposure to interpersonal conflict that undermines their academic security (

Kutuk et al., 2022).

Finally, the results of our study revealed that involvement in aggressive behaviors, both in their traditional and digital forms, is more broadly and consistently associated with lower self-perceived competence in English language skills. This trend aligns with previous research showing that adolescents who actively engage in bullying behaviors face greater academic difficulties, particularly in relation to motivation and self-efficacy in demanding learning environments (

Evans et al., 2019). Contrary to the traditional view that positions victims as the sole affected group, current evidence indicates that aggressors also experience significant deterioration in school adjustment, especially regarding academic self-confidence (

Burger & Bachmann, 2021). This association can be explained by several factors: on one hand, participation in aggressive behaviors has been linked to negative school climates, emotional regulation difficulties, and demotivated attitudes toward learning, all of which diminish academic engagement (

Varela et al., 2021). On the other hand, aggressors themselves tend to exhibit lower levels of academic and social self-efficacy, which directly impacts their performance and participation in activities involving public exposure, such as language tasks (

Evans et al., 2019). In contexts such as English language learning, where error is an inherent part of the process and communicative practice requires confidence and self-regulation, these deficits may have a direct impact on perceived competence and language development (

Jin et al., 2024).

4.1. Educational Recommendations to Promote English Language Self-Efficacy in Adolescents Affected by Bullying and Cyberbullying

The findings of this study demonstrate that both victimization and aggression, especially in digital contexts, are associated with lower self-perceived competence in English as a foreign language. These implications underscore the need for targeted actions involving students, teachers, and families to foster safer, more motivating, and emotionally sustainable environments for language learning.

For students, it is recommended to implement socioemotional programs that strengthen self-efficacy, empathy, and coping skills (

X. Wang et al., 2024). Promoting an educational culture in which making mistakes is seen as a natural part of learning rather than a source of ridicule is essential. In language acquisition, communicative participation is fundamental, and fear of social judgment can seriously hinder oral and written practice. Therefore, it is critical to encourage tolerance for error and safe communicative exposure, as these elements have been shown to enhance academic engagement and learner confidence in adverse contexts (

Jin et al., 2024).

For teachers, it is essential to enhance training for the early detection of bullying behaviors and the implementation of positive classroom management strategies. Research has shown that teachers with higher self-efficacy and specialized training are better equipped to intervene in bullying situations and to create emotionally safe classroom environments that support the learning of all students (

Fischer et al., 2021). In addition, fostering positive teacher–student relationships, offering respectful feedback, and protecting communicative spaces such as oral presentations or debates can help increase students’ language confidence and reduce their vulnerability to bullying (

De Luca et al., 2019).

Regarding families, their involvement must extend beyond academic support. It is crucial to foster a climate of open communication in which children feel safe sharing their school experiences, including situations of discomfort or bullying. Promoting positive attitudes toward language learning and valuing effort over outcomes can further strengthen students’ self-efficacy and motivation. An emotionally supportive family environment may also buffer the stress associated with school exclusion dynamics (

Cheng, 2020).

Finally, it is important that interventions do not focus solely on victims but also include aggressors. Providing them with spaces for reflection, emotional support, and opportunities to redirect their behavior is key to preventing the persistence of violent conduct and its academic consequences. An integrative approach focused on the development of social and communicative competencies is essential, as these skills are often impaired in aggressors, affecting both their linguistic performance and their relationship with the school environment (

Seong, 2024). Creating educational environments where mistakes are not penalized, where respect for difference is an active norm, and where language learning is linked to emotional safety and personal growth is fundamental for improving linguistic competence and reducing the incidence of school and online bullying.

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

This study is subject to several methodological constraints that should be considered when interpreting the findings; therefore, the results must be approached with caution. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the research limits the capacity to infer causality between the variables examined, making it difficult to establish the direction of the observed associations. Secondly, reliance on self-reported measures may lead to potential biases, such as social desirability effects or misrepresentations stemming from subjective perceptions, especially in relation to sensitive topics like involvement in bullying or self-assessed language proficiency. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling restricts the generalizability of the findings to other educational and sociocultural contexts. Thirdly, the stratification of the sample by sex and involvement roles resulted in small sample sizes in some specific subgroups. This resulted in broad confidence intervals for specific binary logistic regression estimates, indicating a degree of instability in these particular parameters. Consequently, these particular findings should be interpreted with caution regarding their magnitude. Finally, as this study assessed self-perceived competence rather than objective linguistic proficiency, actual English levels were not controlled for. While self-efficacy is a meaningful construct in itself, we cannot determine with certainty whether the lower scores found in students involved in bullying dynamics (victims and aggressors) reflect actual skill deficits or simply a belief that they know less.

Nevertheless, the study also possesses important strengths that reinforce the robustness of its results. Among these is the simultaneous inclusion of both victimization and aggression dimensions, in both traditional bullying and cyberbullying contexts, which provides a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. Furthermore, psychometric instruments with high internal reliability were employed, all validated in international contexts, and key control variables were included such as age, body mass index, maternal education level, and weekly physical activity. This approach allowed for the detection of specific associations and gender-based patterns that had not been thoroughly explored in previous research. Moreover, the anonymous administration of questionnaires in controlled school environments and the sex-disaggregated analyses strengthen the study’s internal validity and provide a strong foundation for future longitudinal studies or educational interventions aimed at improving school climate and self-confidence in foreign language learning.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that involvement in bullying and cyberbullying situations, whether as a victim or aggressor, is associated with lower self-perceived competence in English as a foreign language among adolescents. This effect was particularly pronounced among boys, where those who had experienced cybervictimization scored 12.1% lower in listening, 11.6% in reading, 10.6% in speaking, and 8.8% in writing, and were up to six times more likely to report low self-efficacy in writing. Additionally, boys involved in aggression also showed significant differences: traditional bullying aggressors perceived between 13.7% and 16.5% lower competence across all four skills, while cyberaggressors demonstrated lower scores in speaking and writing and were up to five times more likely to show low self-efficacy in reading and writing.

It is worth noting that, although the pattern was more focused, elevated risks were also observed among girls. Cyberaggressors showed particularly strong negative associations in listening, being nearly twelve times more likely to report low self-perceived competence in this skill. Likewise, cybervictimization among girls was associated with substantially lower scores across all four skills, with differences ranging from 5.0% to 10.8%, and with a risk between three and nearly six times greater for low self-efficacy in speaking, listening, and reading.

Based on these results, the importance of implementing measures, not only to preventing school bullying but also to fostering a classroom climate grounded in error tolerance, communicative confidence, and respect for linguistic diversity, is underscored. Such strategies, aimed at both victims and aggressors, may contribute to academic self-confidence while also strengthening emotional well-being and educational equity. These efforts are critical not only for fostering linguistic development but also for cultivating emotionally safe, equitable learning spaces that sustain long-term academic engagement. Future longitudinal studies will be necessary to further explore the directionality of these associations and to evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions across different school contexts.