Abstract

This article examines how 15 Black undergraduates at a public, flagship university in the U.S. perceived the costs and benefits of pursuing a K-12 teaching career. Participants expressed an interest in teaching but were pursuing non-education majors. Our research is based on a secondary analysis of their focus group interview data, drawn from a larger mixed-methods study, and is guided by the Factors Influencing Teaching Choice (FIT-Choice) scale, cost–benefit theory, and the concept of structural racism. Challenging racial inequality and supporting Black youth and communities was important in participants’ career decisions, and they valued K-12 teaching as a means to contribute to these goals. However, their racialized experiences shaped their perceptions that the costs of K-12 teaching outweighed its benefits and led them to reject this profession. We offer suggestions for research on Black youths’ perceptions of teaching as a career choice and strategies for recruiting them into the profession.

1. Introduction

“… for me, the idea of being a teacher is much less realistic just based on the fact that, like, I have way better prospects than being a teacher.”—Economics Major

While the student quoted above expressed a past interest in teaching, like many Black undergraduates, she did not choose to pursue a career in K-12 teaching. Blacks make up only seven percent of those awarded bachelor’s degrees in education (J. E. King, 2024b) and seven percent of the K-12 teaching force (National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 2024). The underrepresentation of Black K-12 teachers, which has been a significant problem since thousands were fired in the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling (Fenwick, 2022), continues to negatively affect Black youth who currently make up 15% of the public-school student population (Institute of Education Sciences (IES), 2023).

Black teachers provide many benefits for Black and non-Black students, including culturally relevant instruction, high expectations for academic success, and improved test scores (Blazar, 2024; Bristol & Martin-Fernandez, 2019; Gershenson et al., 2022). As compared to their White counterparts, Black teachers are more likely to refer Black students to gifted and talented programs and less likely to refer them for disciplinary action (Redding, 2019). Further, Black students who have at least one Black teacher by the third grade graduate from high school and enroll in college at higher rates than Black students who do not (Gershenson et al., 2022). These data indicate the need for more Black teachers, especially given that Black students lag behind White students in many measures of educational success. In response, researchers have sought to understand what discourages Black young people from entering teacher preparation programs (TPPs) and the K-12 teaching profession. Research indicates that racism in K-12 schools is a major deterrent (Goings & Bianco, 2016; Graham & Erwin, 2011) that negatively impacts the experiences of both Black students and teachers (Kohli, 2018).

At present, research on factors that dissuade Black young people from becoming teachers largely focuses on students in high school and in undergraduate TPP programs. There is little data on Black undergraduates who chose not to pursue a K-12 teaching career, and there are several reasons this population should be given more consideration in addressing the Black teacher shortage. First is the potential to recruit them into university TPPs: particularly students with majors that could lead to K-12 teaching (e.g., English or history) (Gainsburg et al., 2024). More importantly, these undergraduates’ perceptions of K-12 teaching can help us to better understand what deters college-going Black youth from pursuing this career.

This article examines perceptions of the costs and benefits of pursuing a K-12 teaching career among 15 Black undergraduates who expressed an interest in but decided not to pursue K-12 teaching. Drawing on data from a larger mixed-methods study, this article is based on secondary analyses of their focus group interviews. Like the broader study, our research is guided by the Factors Influencing Teaching Choice (FIT-Choice) scale, and we also employ the concept of structural racism to contextualize participants’ racialized experiences. The research questions guiding this exploratory study are:

- How do Black undergraduate non-education majors who expressed an interest in teaching perceive the costs and benefits of a teaching career in K-12 public schools?

- How might structural racism help us to understand their perceptions?

2. Theoretical Framework

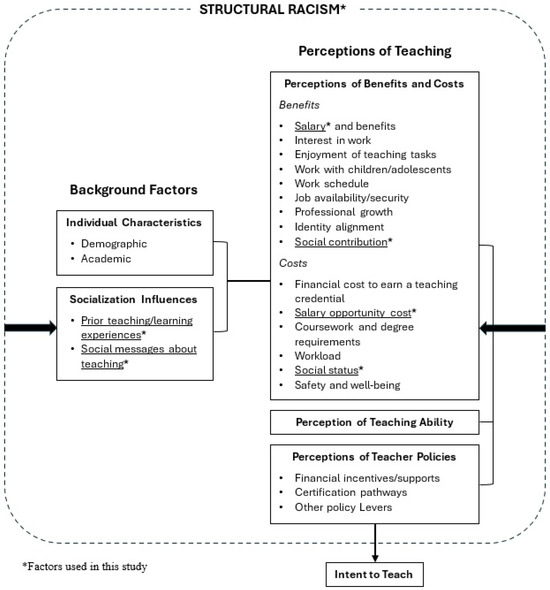

Our theoretical framework (Figure 1) includes an adaptation of the Factors Influencing Teaching Choice (FIT-Choice) scale and the broader concept of structural racism. Watt and Richardson (2007) developed the FIT-Choice scale to understand what influences preservice teachers to teach in K-12 schools. The scale has been used in numerous survey studies, including some with undergraduate and secondary students (Gainsburg et al., 2024; Leech et al., 2019) and has “displayed good construct validity and reliability across diverse samples” (Watt et al., 2012, p. 14). Further, several qualitative studies corroborate the salience of factors identified in the scale (Chu, 2023; Gainsburg et al., 2024; Parr et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework.

Using concepts from the FIT-Choice scale, our framework draws on factors that influence decisions to teach (or not) within the broad categories of background factors and perceptions of teaching; these perceptions, which are shaped by background factors, are delineated into benefits and costs. We focus on six specific factors that are salient in studies with Black students who choose not to teach: (1) prior teaching and learning experiences, (2) social messages about teaching, (3) salary, (4) social contribution, (5) salary opportunity cost, and (6) social status. Teaching and learning experiences can include those at the K-12 or undergraduate level; we presume the former are particularly salient for undergraduates outside of TPPs. Social messages refers to explicit (verbal) and implicit (non-verbal) messages about teaching individuals receive from others, such as teachers and family members.

The next two factors, salary and social contribution, are framed as perceived benefits. Social contribution refers to the value placed on ways K-12 teaching positively contributes to society through supporting youth and advancing social equity (Watt et al., 2012). These valuations are significant motivators to teach among undergraduate and secondary students who aspire to teach (Bianco et al., 2011; Kwok et al., 2022; Leech et al., 2019). Black participants in research on intent to teach also cite racial representation, combating racism, and nurturing Black youth as valued social contributions of teaching (Chu, 2023; Gainsburg et al., 2024; Shipp, 1999). Notably, social contribution is one of only two factors in perceptions of teaching that are altruistic, reflecting the greater overall importance of personal, as compared to social/extrinsic, goals in individuals’ decisions about whether or not to teach, as found in FIT-Choice research.

While salary is framed as a benefit, teachers’ salaries are often perceived as a cost. That is, individuals tend to assess teachers’ salaries in comparison to other professions and perceive a salary opportunity cost—the fifth factor. That is, they perceive a financial loss in choosing teaching over other professions. Studies also indicate that K-12 teaching salaries are often associated with its social status, the final factor on which we focus. Social status refers to the degree to which teaching is viewed as a respected or prestigious occupation and teachers are “perceived as professionals” and “valued by society” (Watt et al., 2012, p. 797). Prior research raises the prospect of social status opportunity cost, which corresponds with Ekehammar’s (1978) vocational research showing that, along with economic interests, individuals consider “social-psychological (e.g., status) goals” (p. 22) when selecting between occupations and academic programs. While perceptions of K-12 teachers’ salaries and social status appear related, FIT-Choice survey research does not identify the nature of their relationship. Qualitative studies indicate that the lower average salary of K-12 teachers, as compared to other professionals (Allegretto, 2023), may be viewed as an indicator of low social status. Or the social status of teaching may be seen as a reason for its comparatively low salaries. We examine how participants perceive the opportunity costs of salary and social status and connections between them in their decisions to reject a K-12 teaching career.

The FIT-Choice scale does not directly address racism. Further, in U.S.-based, FIT-Choice survey research, Blacks are underrepresented, and data are seldom disaggregated by race. However, qualitative studies indicate that Black individuals’ racialized experiences profoundly shape their intent to teach (Gainsburg et al., 2024; Goings & Bianco, 2016; Mccray et al., 2002). To address this issue, we employ the concept of structural racism, which refers to a system of reinforcing societal and institutional practices, policies, and norms that (re)produce racially disparate outcomes in multiple aspects of social life (e.g., education, employment, and wealth accumulation). As Noguera and Alicea (2020) describe, this system reflects “the ways in which the history of [White] racial domination has influenced the organization and structure of society” (p. 52). While decentering interpersonal racism, structural racism gives attention to how racially discriminatory beliefs and actions reinforce systemic racial inequalities, and Taylor et al. (2021) point out that structural racism “affects every aspect” (p. 12) of Black Americans’ lives.

As shown in Figure 1, our theoretical framework presumes that structural racism shapes the nature of the factors that influence Black individuals’ intent to teach, as indicated by prior research. In particular, we are interested in ways systemic racial biases and inequities impact the ways the Black undergraduates in the present study experience and perceive the five factors of focus in our framework. As such, we examine how they describe racialized experiences to identify ways systemic racial biases and inequities shape their socialization influences and views of the costs, benefits, and opportunity costs of teaching in ways that deter them from the teaching profession.

3. Literature Review

The underrepresentation of Black K-12 teachers can be traced to both secondary and undergraduate education. Black secondary students are less likely than White students to express, develop, and maintain an interest in a K-12 teaching career during high school (Lindsay & Blom, 2017; Cooc & Kim, 2023). Further, Black students enrolled in undergraduate TPPs have a lower completion rate than their White counterparts (J. E. King, 2024a). Given the paucity of research on undergraduates outside of TTPs, this review draws largely on studies with high schoolers, which make up the bulk of research on why Black students reject K-12 teaching; it also includes several studies with Black pre-service teachers. We organize this review around four themes connected to the FIT-Choice factors in our theoretical framework: (1) making a social contribution, (2) prior teaching and learning experiences, (3) messages about teaching, and (4) salary and social status.

3.1. Making a Social Contribution

Contributing to the betterment of society attracts many individuals to K-12 teaching, and for Black youths and young adults, these altruistic motivations are often rooted in race consciousness. That is, their perceptions of the value of teaching are associated with their racial identity and desire to challenge racial inequalities that impact Black students and communities (Bianco et al., 2011; Dinkins & Thomas, 2016; Mccray et al., 2002). For instance, the Black, elementary education pre-service teachers in Crenshaw and Yusuf’s (2024) study connected their racial identity to their commitment to diversifying the teacher workforce and supporting Black students, and Black high school students often cite the benefits of Black teachers for Black students (Bianco et al., 2011; Curci et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2004). These perspectives align with research on Black teachers’ positive impacts on Black students (Bristol & Martin-Fernandez, 2019; Gershenson et al., 2022).

Among Black secondary and undergraduate students considering or pursuing a K-12 teaching career, the commitment to redressing racial inequalities extends beyond the K-12 school context. For example, the Black female preservice teachers in Mccray et al.’s (2002) study viewed teaching as a “necessary pathway to self- and group empowerment… [through] their personal and cultural advocacy for the academic, social, and economic success of their [Black] students” (p. 287). These sentiments are reflected in other studies which indicate that Black students value the potential to promote racial equity, inside and outside of schools, through K-12 teaching (Bianco et al., 2011; Dinkins & Thomas, 2016; Leech et al., 2019; Gainsburg et al., 2024; Goings & Bianco, 2016).

At the same time, several studies suggest racial inequality is also associated with deterrents to teaching. Graham and Erwin (2011) concluded that teaching was not a desirable career for many of the 63 Black male high school students in their study because “they were tired of dealing with the pressure and tension of social stratification and ostracism” (p. 411) in school, which they attributed to racism. Likewise, Goings and Bianco (2016) found that experiences with racism in school deterred most of the 22 Black male secondary students in their study from teaching. However, these participants “could see the value in becoming a teacher, especially in terms of giving back to their community and disrupting existing inequities” (Goings & Bianco, 2016, p. 637). Thus, while valuing Black teachers’ capacity to challenge racial injustices, some Black students are discouraged from becoming teachers due to racist encounters in K-12 schools.

Research indicates that, overall, Black secondary and undergraduate students value K-12 teaching as a profession in which to make a social contribution, and this valuation is often connected to their desire to address racial inequality, particularly as it pertains to Black learners and communities. Several survey studies that use the FIT-Choice scale suggest racial identity may have a greater impact on how Black undergraduate and secondary students perceive the value of K-12 teaching, as compared to their White peers (Chu, 2023; Gainsburg et al., 2024). Further, qualitative research indicates that racialized experiences can both motivate Black students to become K-12 teachers and deter them from the profession.

3.2. Prior Schooling Experiences

Individuals’ K-12 schooling experiences have a significant impact on their perceptions of the teaching profession (Watt et al., 2012), and research indicates that, overall, Black secondary students have less favorable experiences than their White counterparts. This disparity is reflected in Leech et al.’s (2019) FIT-Choice survey study of 86 urban high school students’ motivations to teach, in which Black students reported more negative school experiences than White (and Latina/o, and Asian) students. These experiences included White teachers’ low expectations, racial microaggressions and stereotypes (Goings & Bianco, 2016; Marrun et al., 2021), and the disproportionate punishment of Black students (Redding, 2019), which can deter Black youth from enrolling in university TPPs (Dumas & Ross, 2016; Marrun et al., 2021). Black secondary students also cite the dearth of Black teachers and the Eurocentrism of K-12 curricula (Bianco et al., 2011; Goings & Bianco, 2016; Graham & Erwin, 2011; Marrun et al., 2021) as deterrents.

One of the few studies that addresses the prior schooling experiences of Black undergraduates outside of TPPs found they were three times more likely than their White peers to cite “deterrents [to teaching] that were potentially racially charged” (Gainsburg et al., 2024, p. 23). Overall, research indicates interpersonal and institutional racism are significant in Black high school and undergraduate students’ K-12 experiences which, in turn, shape their perceptions of teaching and decisions to pursue or reject this career. Further, not all the experiences reported by Black students in prior research fit neatly into the categories of teaching and learning, as outlined in our framework. Rather, they are encompassed within a broader range of schooling experiences that include social interactions, school policy, and the lack of Black teachers.

3.3. Social Messages About Teaching

Consistent with the FIT choice model, Black students’ perceptions of K-12 teaching are influenced by direct and indirect messages they receive from others, particularly educators and family members. Several studies suggest having a family member who is a K-12 educator can motivate Black youth to teach (Curci et al., 2023; Dingus, 2008; Mccray et al., 2002), and the influence of Black teachers may be particularly significant. Research suggests Black teachers can positively impact Black students’ K-12 schooling experiences and academic outcomes and encourage them to imagine themselves as teachers (Dinkins & Thomas, 2016; Graham & Erwin, 2011). However, many K-12 students have limited exposure to Black teachers. Goings and Bianco (2016) found exposure to only White teachers deterred Black male high school students from teaching. Thus, the underrepresentation of Black K-12 teachers can communicate an implicitly negative message about teaching as a viable career choice for Black students.

Further, some K-12 teachers communicate negative messages about the profession by expressing job dissatisfaction (Bianco et al., 2011; Goings & Bianco, 2016; Marrun et al., 2021; Chu, 2023). For example, a Black high school student in Marrun et al.’s (2021) research described her teachers as “stressed, tired, and angry” (p. 14), which led her to view teaching as undesirable. Black students also report how teachers may communicate that K-12 teaching does not pay well and lacks intellectual rigor (Curci et al., 2023; Goings & Bianco, 2016; S. H. King, 1993). The latter view is captured by a statement by a Black high school student in Chu’s (2023) study who was told, “you are so bright, you should become a doctor, a lawyer or anything else [but a teacher]” (p. 16). Research suggests high-achieving students are particularly likely to be explicitly discouraged from teaching (Graham & Erwin, 2011; Scott & Rodriguez, 2015).

Black students receive implicit and explicit messages about teaching that can be both motivating and discouraging, and research indicates racial bias can play a role in negative messages from White educators (Marrun et al., 2021; Graham & Erwin, 2011; Scott & Rodriguez, 2015). Among Black students, the effect of social messages appears most influential for those who have had negative interactions with White teachers and positive interactions with Black teachers and girls and young women with female family members who are teachers (Dingus, 2008; Curci et al., 2023; S. H. King, 1993; Mccray et al., 2002). At present, there is little research on the influence of social messages on their career decisions of Black undergraduates outside of TPPs.

3.4. Salary and Social Status

Research with Black secondary and undergraduate students not enrolled in TPPs shows they tend to have negative views of K-12 teachers’ salaries and social status (S. H. King, 1993; Shipp, 1999; Mack et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2004). Among the 127 Black high school honor students in Mack et al.’s (2003) study, higher salaries and greater respect for teachers were cited as the two most influential factors that would make K-12 teaching a more attractive career. Similarly, in a survey study with 297 undergraduates with various majors, salary and “professional status or prestige” (Gainsburg et al., 2024, p. 19) were among the weakest attractors to teaching, and Black participants were more than twice as likely as Whites to cite lack of social status as a deterrent to teaching. Further, Shipp’s (1999) research suggests salary may be more important to the career decisions of non-education majors, as compared to education majors.

In interview-based research, Black secondary students often associate salary with social status, as cited by a Black, male high school student in Goings and Bianco’s (2016) study who said, “teachers don’t make a lot of money and people want to make a lot of money to get out of the community where they live now…. Athletes, doctors, judges [are respected]” (p. 639). This quote also reflects some Black students’ belief that K-12 teaching will not provide for economic mobility and stability (Dinkins & Thomas, 2016). While the desire for financial stability is not unique to Black students, it may be particularly influential in their career decisions, given the disproportionately low average incomes and wealth of Black families (Perry et al., 2024). The importance of economic needs is reinforced by the consistent call for financial incentives (e.g., tuition reimbursement and loan forgiveness) in recruiting Black students into university TPPs (Chu, 2023; Dinkins & Thomas, 2016; Gainsburg et al., 2024; Graham & Erwin, 2011).

Black secondary and undergraduate students often consider teachers’ experiences and the wages and prestige of other careers and in evaluating the salaries and social status of K-12 teaching (Bianco et al., 2011; Goings & Bianco, 2016; Graham & Erwin, 2011). Some cite the societal devaluing of K-12 teaching and how Black teachers face disrespect from students and racial bias from White colleagues, administrators, and parents (Gainsburg et al., 2024; Graham & Erwin, 2011; Mack et al., 2003; Marrun et al., 2021). As a result, they conclude that teachers’ salaries do not offset the racial biases Black teachers endure and the demands of teaching, more generally. As one Black high school student in Smith et al.’s (2004) study stated, “They don’t pay teachers enough for what they all have to endure” (p. 80).

It is clear that Black students’ decisions to reject K-12 teaching as a career are influenced by their perceptions of the opportunity costs of teaching as low-paying and lacking social status, particularly as compared to other professions. However, some Black young people do choose to teach “despite perceived low salary and social status” (Watt et al., 2012, p. 12). Research indicates that, for these young people, opportunities to support Black students and communities, through K-12 teaching, outweigh the disadvantages of the profession (Curci et al., 2023). How Black undergraduates who reject teaching weigh relationships among social contribution, salary, and status in their career decisions remains unclear, as there is little research on this population.

4. Methods

4.1. Study Site and Participants

This article uses data from a broader, sequential mixed-methods study of career decisions and perceptions of K-12 teaching among undergraduate students at a public university in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. The survey stage was conducted in 2020. Among survey respondents (n = 1644), the 1225 who indicated a past, present, or future interest in K-12 teaching were invited to participate in a focus group interview in spring 2021. A total of 140 respondents joined one of 30 focus groups, with an average or five participants per focus group. They opted to participate in a general focus group, or one composed of students from a particular racial/ethnic background or academic major area. This article uses data from 15 of the 161 focus group participants who identified as Black and were not education majors. They included two freshmen/women, three sophomores, five juniors, and five seniors. Fourteen identified as female and one as male. Six were pursuing (non-education) social science majors, three arts-humanities, four STEM, and two business. Nine participated in two focus groups for Black students, four in two STEM groups, one in a social sciences group, and one in a general group; their excerpts were drawn from across six different focus groups/transcripts.

4.2. Data Collection

Focus group interviews lasted 90 min; all interviewees were asked the same questions, adapted from the survey items, and the semi-structured interview protocol allowed for elaboration on survey findings. Interview questions addressed career decisions, perceptions of the K-12 teaching profession, teachers’ salaries, and social messages about teaching. Due to COVID-19, focus group interviews were conducted via Zoom, through which we audio recorded and generated transcripts. After ensuring their accuracy, transcripts were uploaded into NVivo, which was used to organize, code, and retrieve data.

4.3. Data Analysis

This article draws on two stages of analysis. In the initial analysis of the 30 interview transcripts from the broader study, a seven-member research team conducted four rounds of coding using NVivo version 12 qualitative data analysis software. Data were coded deductively, based on the broader study’s theoretical frameworks and prior research, and inductively, to identify data related to participants’ perceptions of K-12 teaching not captured by the deductive codes. In the first three rounds of coding, research team members employed individual and collective approaches to coding 23 transcripts. Each round of coding was followed by a constant comparative strategy (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). To do so, we merged individual members’ coding for each transcript in NVivo, and then the entire team analyzed each code and its associated data to ensure conceptual consistency among coders and codes and to generate a final code list. In the fourth round, five researchers re-coded (as needed) and coded all 30 transcripts, using the final code list. This process resulted in a reliable base of coded data that evidenced perceptions of FIT-Choice factors and costs and benefits of K-12 teaching.

In our secondary data analysis for the present paper, we (the authors) coded the 15 Black participants’ interview data for evidence of structural racism. These codes included race, racism, racial inequalities/disparities, and racial discrimination. We looked for relationships between aspects of structural racism and data associated with the six factors of focus in our theoretical framework. Based on patterns we identified across participants’ data, we developed three broad categories—financial, social, and workload. The last category reflects a factor framed as a cost in the broader FIT-Choice model that was not initially examined but emerged as important in data analysis. We then examined data associated with our structural racism codes, within each category, to identify connections between racialized experiences and perceptions of teaching. Through these analyses, we identified four themes that reflected how and why participants perceived K-12 teaching career in particular ways, as connected to structural racism. They include: (1) K-12 teaching as Important but Undervalued Work, (2) Pursuit of Financial Stability, (3) The Myth of Black Intellectual Inferiority, and (4) The “Black Tax.” The last two themes were unexpected in the context of prior research and the FIT-Choice factors on which we focused; they emerged iteratively through data analysis. We identify how these two themes align with and extend our conceptual framework.

4.4. Study Limitations

Due to the small sample size, study findings cannot be generalized to all Black undergraduates outside of TPPs and we cannot analyze data by participants’ majors. Importantly, because the concept of structural racism, which guided our secondary analysis, was not part of the original study’s framework, the interview protocol did not directly address race or racism; participants voluntarily raised these issues. Further, participants in focus groups that were racially/ethnically heterogeneous spoke less about racialized experiences than those in groups composed of all Black interviewees (facilitated by a Black researcher). In research on this topic, Black participants may be most comfortable among peers who share their racial/ethnic identity and with Black interviewers who directly address issues of race and racism.

4.5. Researcher Positionality

We (the authors) are Black women teacher educators and former public high school teachers who attended K-12 public schools. The first author came to K-12 teaching through an emergency credential and taught Black and Latina/o high school students in urban schools. The second author completed a traditional, university-based teacher education program and taught, primarily, Black youth in a rural setting. The third author entered the field through a teacher residency program in an urban school district and taught Black and Latina/o youth in grades 6–12. Our prior experiences as students and teachers and varied pathways into K-12 teaching and teacher education provided us with valuable insights into study participants’ perceptions of teaching. However, as teacher educators dedicated to diversifying the K-12 workforce, our work had largely focused on why Black young people should become teachers. In analyzing participants’ data, we interrogated our preconceptions about K-12 teaching, based on our professional roles and prior experiences of teaching and learning, and actively “listened” to the data to ensure a genuine account of how and why the Black undergraduates in this study chose not to pursue a career in teaching.

5. Findings

Given that participants were pursuing non-education majors, expectantly, our analyses revealed more perceived costs than benefits of a K-12 teaching career, and the role of structural racism was far more evident in reported costs. Below, we explicate these findings within four themes: (1) K-12 teaching as important but undervalued work, (2) the pursuit of financial stability, (3) dispelling the myth of Black intellectual inferiority, and (4) the “Black Tax.”

5.1. K-12 Teaching as Important but Undervalued Work

In describing what was important to them in a future career, most study participants said they wanted to make a social contribution. For example, a social science major said she desired a career “that makes me feel like I’m making an impact on the world,” and a business major wanted to “work[ing] with people or with clients who feel underserved or kind of making sure their voices are heard.” All participants viewed K-12 teaching as a career in which one could positively contribute to society. More specifically, they viewed fostering children’s development as a benefit of teaching, and several discussed teaching Black and other children of color as particularly vital. Thus, overall, participants valued K-12 teaching: a sentiment that was voiced by multiple participants in describing its importance.

Business major: I think for sure the influence you can have on children’s education… I think a teacher can have a big influence on how that child eventually grows up.

Arts-humanities major: I think contributing to nurturing a child. I mean, like I think, I think it’s a beautiful thing to be able to help, you know, contribute to raising a child or another human being in the world.

Social Sciences major: And being a positive representation or a positive role model for [students]. Especially for students of color in a field that’s really dominant with white females, I think that being a Black female teacher is super important thing.

However, in many instances where participants mentioned social contributions, they followed with statements regarding how K-12 teaching is undervalued and how teachers are unappreciated, underpaid, and not given adequate support. For example, one social sciences major said she admired teachers for “being able to connect with kids on like a really deep level.” She continued by saying, “But I’ve also heard that teachers, even though they’re kind of regarded as these really important figures in our society, they also don’t really get enough support within their own like administration and schools.” In describing her own experience as a K-12 student, another social sciences major said,

Like, my teachers were really instrumental in making me the person that I am now, but to be a teacher, as a career, I don’t really see myself doing that. It doesn’t pay well, but teachers are instrumental. Like, they do a lot, but they are not really appreciated for the work that they do.

Some participants discussed how social messages about teachers, through the media and from current teachers, reinforced their views of K-12 teaching as both important and undervalued. For example, some talked positively about how teachers dealt with the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. A STEM major said, “regarding COVID, I have a lot more respect for teachers… because I think we all got to see how teachers had to like completely flip everything to make school work.” However, COVID also revealed a disregard for teachers, particularly as related to expectations that they return to school at the height of the pandemic. An arts-humanities major, whose aunt was a teacher, said COVID made her “realize how expendable teachers are… They’re trying to push them back into school, but they weren’t super high on the vaccine list.” Similarly, another arts-humanities major said school districts were “Trying to force teachers to go back to school before it is literally safe for public health… COVID, specifically, has just shown again how teachers are disrespected in this society.” The treatment of teachers during the pandemic was particularly worrying for an arts-humanities major who was considering teaching in the future:

I have gotten a lot of anxiety just because of how I’ve seen teachers being treated because of COVID, how their concerns have oftentimes been thrown away… and I do get concerned over that, and I want teachers to be cared for more, for their voices to be cared for by school districts and by people at large.

Several participants speculated about why K-12 teaching is undervalued. A STEM major believed that because most people go through the K-12 education system, there is a widespread belief that “anyone can be a teacher, so it’s not given credit.” An arts-humanities major implicated the role of sexism and the feminization of teaching, stating, “it’s [K-12 teaching] not respected, because it’s seen as, ‘Well that’s a woman’s job,’ and women’s work is not as important, because you’re just dealing with children and babies all day.” Other participants also attributed the devaluing of teachers to their work with children. For instance, an arts-humanities major associated the lower “prestige” of K-12 teachers, as compared to college professors, with the “second-class” status of children. A business major said early childhood educators were particularly devalued due to their focus on social skills rather than the “hard skills that [students] will utilize for college,” as taught in high school.

Most of the Black undergraduates in this study expressed the desire to make a positive contribution to society in their future careers, and they perceived K-12 teaching as a career in which they could make such a contribution. In particular, they cited supporting children’s development as important work. While they all believed the social contribution of K-12 teaching was important, they perceived this contribution as devalued in society, describing disrespect and lack of appreciation for teachers. The ways in which they saw the benefit of social contribution diminished by the cost of low social status deterred them from teaching.

5.2. The Pursuit of Financial Stability

In total, 14 of the 15 participants did not believe a teacher’s salary would enable them to be financially stable, as reflected in the ways they assessed the economic costs of pursuing a K-12 teaching career. More specifically, they talked about relatively low teacher salaries in the context of intergenerational wealth, student loans, and access to higher-paying careers. In explaining Black underrepresentation in the K-12 teaching force, an arts-humanities major said,

[Black people are] establishing generational wealth… being this second-class citizen or whatnot. So being a teacher just kind of keeps you in this cycle [of poverty]. If I think to look for a career path and it doesn’t yield any financial benefits in a way that some Black people may need to help themselves in that way, that’s just, like, one reason.

A social sciences major expressed a similar sentiment:

… if you’re, like, a minority, and you come from a low-income district or low-income area, I feel like you’re not going to want to be stuck in that same cycle of poverty for you and your future family. So, I think that’s really important.

Four participants also talked about paying off educational debt as central to their career decisions. For instance, a social sciences major said she desired an “above average income just because I have student loans to pay off, and it needs to be sustainable enough to pay them off before like a 10-year mark.” An arts-humanities student said she wanted “to be in a position to save money so that I can pay the loans that I accrued in my undergraduate career.” Referring to research on racial disparities in educational loan debt, an arts-humanities major weighed Black undergraduates’ desire to serve Black youth against a teacher’s salary:

I read a study that Black and White students enter college at the same economic rate, like, middle class, but because they have more debt, Black students end up going down in the socioeconomic level… I think many of us do want to help Black students in school, but I can’t leave college with $150,000, $200,000 in debt and I get a $65,000 a year paycheck. I can’t pay off my student loans like that.

Importantly, this participant suggested that a teacher’s salary, in combination with educational debt, could actually lead to downward economic mobility.

Two participants alluded to the fact that the cost of an undergraduate degree in education (e.g., tuition, fees, and room and board) was the same as other degrees that led to higher salaries. Thus, they saw pursuing K-12 teaching as impractical when they had access to more lucrative career options. For instance, a social sciences major characterized an education major in the following way:

Why am I paying this much for a major that’s not going to be paying me much back? It’s not like I’m paying for medical school bills, and then I’m going to be making $200,000. That just makes no sense to be paying so much for a major for a job that isn’t going to be paying me like that.

Also, weighing tuition costs against projected salary, a social sciences major said her mother, who was a teacher, would be “upset… if I were to, like, get a job that pays less than I pay in a year to go to this school.” Coincidentally, nearly half of the participants suggested financial incentives, such as loan forgiveness, scholarships, and tuition remission, might attract more Black undergraduates to teaching.

Participants in this study perceived several financial costs of pursuing a K-12 teaching career: loss of future income, difficulty paying back student loans, and being unable to build generational wealth. While these concerns are not unique to Black undergraduates, as compared to White students, the economic consequences of structural racism can exacerbate the obstacles they face in achieving financial stability. As participants discussed, these include Black families’ lower wealth and income and Black collegians’ greater educational debt, as compared to Whites’ (Houle & Addo, 2019). Thus, they not only determined the opportunity cost of a teaching salary in comparison not only higher-paying professions, but also to family resources. Overall, participants did not believe a teacher’s salary would provide the economic security they sought.

5.3. The Myth of Black Intellectual Inferiority

Four participants discussed another perceived cost we did not expect; pursuing a K-12 teaching career would not allow them to disprove perceptions that Black people are intellectually inferior to other racial/ethnic groups. This myth of Black intellectual inferiority is a long-standing and widely held racial stereotype that, in the U.S., has been promulgated in multiple research disciplines, including education (Campbell, 2020; Winston, 2020). Due to structural racism, Black Americans fare worse than other racial/ethnic groups on many social, economic, and educational indicators, which has reinforced this myth (Miller, 1995).

In alluding to perceptions of Black intellectual inferiority, participants cited how neither undergraduate education programs nor the K-12 teaching profession were considered intellectually demanding. Therefore, they did not view this career trajectory as an opportunity to demonstrate their intellectual capabilities or those of Black people, more generally. Explaining the underrepresentation of Black teachers, an arts-humanities major talked about a desire in the Black community to show “that we’re just as intelligent… [and] teaching is not seen as a profession that you need to be super smart to do or you have to have some kind of high level of degree or education.” Two other participants expressed similar sentiments. A social sciences major said her family members talked about K-12 teaching “as if it’s like an easy thing to just do,” and a STEM major said,

… teaching is one of the things that people think anyone can do, like, “Oh, anyone can be a teacher.” I can understand, as a minority, when you feel like you have to prove yourself, and [teaching] just doesn’t feel like it’s making an impact or statement. Like, it just doesn’t feel like an accomplishment.

As compared to K-12 teaching, participants framed higher-status professions and the academic preparation required to secure them as more viable means for Black people to demonstrate their capabilities. This was voiced by a social sciences major who stated,

… having a more difficult major and ending up in a career that seems more prestigious, and you get paid more is more appealing to Black people. And it stands for something. It seems like it stands for something greater than teaching just because you get paid more and you ultimately seem like you work harder for your degree.

Two other participants talked about a desire among individuals in marginalized groups to “prove” they are capable of success in career fields considered more intellectually rigorous than K-12 education. An arts-humanities major stated,

I also think there’s a push to want to prove something… as minorities, that we’re just as smart, we’re just as capable, we’re just as intelligent. So, I’m going to prove that I can not only be a teacher. I can be a lawyer. I can be a doctor. I can be an engineer.

Similarly, a social sciences major said,

… some of us [Black people] feel the need to prove something so badly that we go for the things that are the most challenging, like engineering fields, where… it requires, like, more effort, just because that shows that we’re capable of doing it too.

In discussing desire among Black people to prove they are intellectually able, the four participants communicated that neither K-12 teacher education programs nor the teaching profession were cognitively demanding, and they believed this perceived lack of rigor contributed to the underrepresentation of Black teachers. They viewed choosing a K-12 teaching career as opportunity cost, in terms of “proving” their own intellectual capacity, as compared to selecting other professions they perceived as more intellectually demanding and respected. Importantly, data indicate that these four participants considered the social status of teachers in relationship to the status of Black people in the U.S., which has been depreciated by structural racism and the myth of Black intellectual inferiority.

5.4. The “Black Tax”

Seven of the 15 participants described how, as compared to White teachers, Black teachers are both devalued and held to higher expectations, which they saw as another cost of K-12 teaching. Their descriptions align with the “Black Tax,” a term used in higher education to refer to systemic ways Black faculty are racially marginalized and their labor exploited. This is reflected in how Black educators, especially women, are subject to racial biases in the workplace, must work harder than their White colleagues to prove their value and competence, and have their voices ignored in decision-making processes (Griffin et al., 2011; Griffin & Reddick, 2011). The Black Tax also includes expectations that Black educators take on unpaid service work, including academic and social support for students of color. These workplace experiences have also been reported by Black K-12 teachers (Kohli, 2018).

Study participants described K-12 Black teachers’ experiences that reflect the Black Tax, particularly in schools where the majority of teachers are White. For example, a social sciences major said Black teachers are “held to a higher standard” than White teachers. She continued,

… you’ll also have to carry the burden, if you’re in a white setting, of being the token Black teacher. So, you have to know about every issue. You have to know about everything that’s going on because you’re Black. So, you have to know, literally, everything.

Discussing Black educators’ experiences within a predominantly White teaching staff, another social sciences major recounted how she heard from Black teachers that “it’s just like a harder experience for them to really be understood or respected as a teacher.”

Another cost of K-12 teaching reported by participants is the everyday work of supporting Black and other students of color. While they believed this work was important, they also characterized it as overwhelming for Black teachers. Drawing on her experience as a student in a high school with “few Black female teachers,” an arts-humanities major said, “all the Black students will run to them and treat them almost like guidance counselors or almost like mothering figures.” Similarly, a STEM major said, “if you’re a Black teacher and, like, maybe [in] a Whiter school, then because the Whiter school doesn’t know how to deal or like care for their Black students, all of the Black students run to the [Black] teacher. It’s just too much.” These and other participants intimated that White teachers could not adequately meet the needs of Black students, which placed an inequitable burden on Black teachers. Expressing empathy for students of color, based on her experience as a K-12 student, an art-humanities major speculated how, as a Black teacher, addressing the multiple needs of students of color would be taxing and undercompensated. She said,

I know what it’s like to be the only little brown face in a white space, but at the same time, that is not my job. I can’t, you know, be giving a test, but also helping you write your college essay but also helping you deal with your math teacher who is racist. It’s like, that’s not the job I signed up for, and that’s not the job I’m getting paid for.

These seven participants perceived a Black Tax in K-12 education through their prior experiences of teaching and learning, as K-12 students, and social messages from K-12 teachers. As history major voiced, participants acknowledged, “there’s racism in all types of fields,” which they could not necessarily avoid in their chosen professions. However, the Black Tax was among the compounding costs that deterred them from a career in K-12 teaching. The Black Tax theme can be connected to both teachers’ social status and workload. Findings indicate Black undergraduates in this study believed the lower social status of Black teachers (in terms of respect and perceived intellect), as compared to White teachers, resulted in greater workloads and higher expectations. They also attributed this racial disparity to White teachers’ inabilities to adequately support Black and non-Black students of color. Their perceptions align with the experiences of Black educators in higher education, as tokenized, expected to provide unpaid labor, and having to prove their worth—conditions that are (re)produced through structural and institutional racism in in U.S. schools and society (Griffin et al., 2011; Noguera & Alicea, 2020).

5.5. Summary

Our findings indicate how the effects of low salaries and low social status, as deterrents to teaching, can be exacerbated by racism among Black students. Due to structural racism in the U.S., Black people have been stymied in building intergenerational wealth and perceived as intellectually deficient professionals who must over-function, as compared to their White counterparts, to prove their value. Study participants valued and, at some point, considered K-12 teaching as a way to make a positive social contribution. However, their personal concerns about financial instability, disproving the myth of Black intellectual inferiority, and the Black Tax deterred them from teaching, which they perceived as low-paying and low-status profession.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined how 15 Black undergraduates outside of education perceived the costs and benefits of K-12 teaching as a career choice. Given that participants were pursuing other careers, it is not surprising that they perceived more costs than benefits. While some of our findings align with the Fit-Choice scale, others indicate the limitations of this framework. Our use of the concept of structural racism exposed how racial inequalities influenced participants’ perceptions in ways that deterred them from pursuing K-12 teaching. Our findings suggest that addressing the shortage of Black teachers will require educators and policymakers to challenge the ways structural racism is manifest in K-12 education.

Consistent with research showing that making a social contribution is among “the most frequently nominated reasons for choosing teaching as a career” (Watt et al., 2012, p. 2), study participants highly valued K-12 teaching as a way to positively impact the lives of youth and challenge social inequality. They gave precedence to serving Black and other students of color, as found in studies on Black pre-service teachers’ motivations to teach (Dinkins & Thomas, 2016; Mccray et al., 2002). However, this social value was not offset by the costs they perceived, some of which they associated with racial inequality.

Like prior research with high school students, participants identified racism in K-12 schools as a significant cost of teaching; however, they emphasized Black teachers’ experiences more than their own or Black students’, more generally. This may be because undergraduates are further removed from their K-12 experiences than secondary students, and the career focus of this study may have predisposed participants to focus on teachers. Participants offered first-hand and more general accounts of Black teachers being subject to racial bias, tokenization, and disrespect: phenomena that are well documented in the research literature (Kohli, 2018). Thus, in addition to negatively impacting Black teachers’ working conditions, racism in K-12 schools may, as our findings suggest, deter Black students who witness racial bias against Black teachers from pursuing teaching.

Teacher workload emerged as a significant factor in how participants viewed the costs of teaching. This factor was not included in our theoretical framework because we did not anticipate how participants’ experiences as K-12 students would foster acute awareness of the demands of teaching. Some participants cited helping students of color to navigate racism in school as part of Black teachers’ racially inequitable workloads. In this way, the primary benefit of K-12 teaching—supporting students—was also a cost. Our findings suggest this dual designation may be explained by the Black Tax. While Black educators may desire to support students of color, they are often disproportionately charged with and inadequately compensated for these efforts (Griffin et al., 2011; Griffin & Reddick, 2011). Kohli (2018) connects this underpaid and under-valued work to long-standing economic structures in the U.S. that exploit Black labor. Further, the interconnected burden of racism among both Black teachers and students is indicative of institutional racism “on structural, macro levels, which include policies, infrastructures, and schoolwide practices” (Kohli, 2018, p. 314). Our findings indicate that racialized experiences mediated how participants perceived the relationship between Black teachers’ social contributions and workloads.

Not included among workload demands participants described was intellectual rigor. While they viewed the work of Black teachers as challenging, they did not perceive K-12 teaching—as an academic pathway or a profession—as intellectually demanding, particularly as compared to other professional fields. Intellectual rigor was significant to participants who expressed concerns about proving their capabilities, through which they evoked the myth of Black intellectual inferiority (Miller, 1995). They cited this burden of proof as a reason for the greater workloads and higher expectations Black educators face, compared to their White colleagues, as described in prior research on the Black Tax (Griffin et al., 2011; Griffin & Reddick, 2011; Kohli, 2018). A fuller understanding of the role the Black intellectual inferiority stereotype plays in Black undergraduates’ (and other Black individuals’) perceptions of teaching requires further research. Among our participants, this stereotype emerged as an opportunity cost in choosing K-12 teaching over other careers perceived as more intellectually demanding.

For The Black undergraduates in this study, the cost of teaching was also financial, reflecting relatively low teacher salaries (Allegretto, 2023) as a deterrent to teaching. Participants expressed interrelated concerns about family resources and paying off student loans, which may particularly be significant to Black undergraduates. Black families lag behind White families in terms of wealth and income (Sullivan et al., 2024), and Black collegians take on more educational debt and experience more difficulty repaying it than their White counterparts (Houle & Addo, 2019). Houle and Addo (2019) attribute these disparities to systemic “racial economic inequalities [that] are perpetuated across generations” (p. 563). Thus, we found evidence of structural racism in how participants perceived the economic, professional, and social status opportunity costs of K-12 teaching.

Implications for Policy, Research, and Practice

In considering their prior teaching and learning experiences, many young people make decisions about pursuing a K-12 teaching career before they apply to college, as their perceptions of this profession are formed through years of observation in K-12 schools and social messages from teachers and other adults. Therefore, our study implications are largely directed toward cultivating pre-collegiate interest in teaching and providing supports for Black students to enroll in university-based teacher preparation programs.

To increase the number of Black teachers, Black K-12 students must have access to college and exposure to the benefits of teaching. These students should be urged to participate in dual enrollment and K-12/college partnerships, which increase the likelihood that they will enter and be prepared for college (Bianco et al., 2011; Curci et al., 2023). Furthermore, since many Black individuals are attracted to teaching as a way to challenge racial inequities and uplift Black communities, colleges and universities should partner with high schools to provide pre-collegiate TPPs that emphasize anti-racism and social justice (Graham & Erwin, 2011). Prior research suggests such equity-focused programs are particularly attractive to Black students (Chu, 2023; Curci et al., 2023; Goings et al., 2018).

We acknowledge that the current political climate in the U.S. discourages efforts towards racial equity, anti-racism, and social justice in educational programming in both public and private institutions. However, these efforts are vital to increasing the number of Black teachers, who “benefit all students—with decreases meaningful in absenteeism and increases in test scores” (Blazar, 2024, p. 458). Moving forward, equity-based TPPs might have to be configured in ways that do not run afoul of federal policy priorities but still attract Black aspiring teachers.

Given Black individuals’ disproportionately low levels of family income and wealth and high levels of educational debt, incentives like scholarships and loan forgiveness may increase the number of Black students who enroll in teacher education programs. A recent RAND report (Steiner et al., 2022) suggests such financial incentives and strategies that “increase program completion and licensing exam pass rates” (p. 18) among teacher candidates of color will help to racially diversify the K-12 teaching force. In addition, it may also be important for universities to promote perceptions of teacher education as intellectually demanding. This might be achieved through rigorous and critical pedagogical and theoretical course offerings, internship requirements, and expectations for subject-specific content mastery.

While slightly improved since 2015 (Allegretto, 2023), further raising K-12 teachers’ salaries can attract more individuals, across racial/ethnic groups, to teaching. In addition, increasing teacher professionalism, such as granting teachers more autonomy and more power in education policy decisions, may help to combat perceptions of K-12 teaching as a low-status profession (Bergey et al., 2019). We also believe teacher professionalism will be enhanced by valuing those who remedy the most pressing problems in K-12 education and alleviate racial opportunity gaps among students: Black teachers are doing this work.

In attracting more Black individuals to teaching, we are concerned about the racially hostile workplaces they may encounter. Thus, it is vital to combat racism in K-12 schools, which remains a persistent problem (Kohli, 2018) that can deter Black students from becoming teachers. To improve the workplace experiences of Black teachers, whom Black students look to as examples of their future possibilities, researcher suggest affinity groups, mentorship, anti-bias training for teachers and administrators, and strengthening institutional commitment to racial equity (Kohli, 2018; Steiner et al., 2022). Given that Black educators often feel unheard, we also recommend accountability systems through which their concerns about racial bias can be registered and addressed.

While many of our findings align with factors outlined in the FIT-Choice scale, this framework, which does not directly address racism, is limited in helping us to fully understand underlying reasons for Black individuals’ perceptions K-12 teaching. In this study, qualitative methods and the concept of structural racism allowed us to uncover vital connections between participants’ racialized experiences and how they assessed costs and benefits as related to FIT-Choice factors. We advocate for theoretical frameworks with an explicit focus on race and racism in both survey-based and qualitative research with Black participants. BlackCrit, which captures “how the specificity of (anti)blackness matters in explaining how Black bodies become marginalized, disregarded, and disdained in schools” (Dumas & Ross, 2016, p. 415) may be particularly instructive. Further, there is a need for more research that captures Black students’ voiced perspectives on what deters them from and might attract them to the K-12 teaching profession.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.B. and T.M.M.; methodology, T.M.B.; software, T.M.B.; validation, T.M.B., T.M.M. and C.D.B.; formal analysis, T.M.B. and T.M.M.; investigation, T.M.B.; resources, T.M.B.; data curation, T.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.B. and T.M.M.; writing—review and editing, T.M.B., T.M.M. and C.D.B.; visualization, T.M.B.; supervision, T.M.B.; project administration, T.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Division of Research, University of Maryland, College Park (protocol code 1510239-6 and date of approval, 14 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | We excluded one Black participant whose data were inadvertently not recorded. |

References

- Allegretto, S. (2023). Teacher pay penalty still looms large: Trends in teacher wages and compensation through 2022. Economic Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-in-2022/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Bergey, B. W., Ranellucci, J., & Kaplan, A. (2019). The conceptualization of costs and barriers of a teaching career among Latino preservice teachers. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M., Leech, N. L., & Mitchell, K. (2011). Pathways to teaching: African American male teens explore teaching as a career. Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 368–383. [Google Scholar]

- Blazar, D. (2024). Why Black teachers matter. Educational Researcher, 53(8), 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristol, T. J., & Martin-Fernandez, J. (2019). The added value of Latinx and Black teachers for Latinx and Black students: Implications for policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C. L. (2020). Getting at the root instead of the branch: Extinguishing the stereotype of Black intellectual inferiority in American education, a long-ignored transitional justice project. Law & Inequality, 38(1), 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y. (2023). What motivates high school youths to want to teach? Narratives of homegrown aspiring teachers. Urban Education, 60(4), 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooc, N., & Kim, G. M. (2023). Racial and ethnic disparities in adolescent teaching career expectations. American Educational Research Journal, 60(5), 882–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, A., & Yusuf, A. (2024). Do you see me? An examination of Black pre-service teacher experiences in a teacher preparation program. Journal of Education, 204(4), 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curci, J. D., Johnson, J. M., Gabbadon, A. T., & Wetzel-Ulrich, E. (2023). Expanding the pipeline to teach: Recruiting future urban teachers of color through a dual enrollment program. Urban Education, 55(2), 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingus, J. E. (2008). ‘Our family business was education’: Professional socialization among intergenerational African-American teaching families. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 21(6), 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkins, E., & Thomas, K. (2016). Black teachers matter: Qualitative study of factors influencing African American candidates success in a teacher preparation program. AILACTE Journal, 13(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, M. J., & Ross, K. M. (2016). “Be real Black for me”: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Education, 51(4), 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekehammar, B. (1978). Toward a psychological cost-benefit model for educational and vocational choice. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 19(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, L. T. (2022). Jim Crow’s pink slip: The untold story of Black principal and teacher leadership. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainsburg, J., García, M. G., Stone, D. J., & Goldschmidt, P. G. (2024). Undergraduates’ views on teaching careers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 51(2), 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenson, S., Hart, C. M. D., Hyman, J., Lindsay, C. A., & Papageorge, N. W. (2022). The long-run impacts of same-race teachers. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(4), 300–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goings, R. B., & Bianco, M. (2016). It’s hard to be who you don’t see: An exploration of Black male high school students’ perspectives on becoming teachers. Urban Review, 48(4), 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goings, R. B., Brandehoff, R., & Bianco, M. (2018). To diversify the teacher workforce, start early. Educational Leadership, 75(8), 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A., & Erwin, K. D. (2011). “I don’t think Black men teach because how they get treated as students”: High-achieving African American boys’ perceptions of teaching as a career option. Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 398–416. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, K. A., Bennett, J. C., & Harris, J. (2011). Analyzing gender differences in Black faculty marginalization through a sequential mixed-methods design. New Directions for Institutional Research, 583(151), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K. A., & Reddick, R. J. (2011). Surveillance and sacrifice: Gender differences in the mentoring patterns of Black professors at predominantly White research universities. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1032–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J. N., & Addo, F. R. (2019). Racial disparities in student debt and the reproduction of the fragile Black middle class. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 5(4), 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES). (2023). Report on the condition of education 2023. National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2023/2023144.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- King, J. E. (2024a). Data Update: Degrees and certificates conferred in education. American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE). Available online: https://aacte.org/report/data-update-degrees-and-certificates-conferred-in-education/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- King, J. E. (2024b). Data Update: Teacher preparation program trends 2010–2011 to 2020–2021. American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE). Available online: https://aacte.org/report/data-update-teacher-preparation-program-trends-2010-11-to-2020-21/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- King, S. H. (1993). Why did we choose teaching careers and what will enable us to stay?: Insights from one cohort of the African American teaching pool. Journal of Negro Education, 62(4), 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R. (2018). Behind school doors: The impact of hostile racial climates on urban teachers of color. Urban Education, 53(3), 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A., Rios, A., & Kwok, M. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ motivations to enter the profession. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(4), 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N. L., Haug, C. A., & Bianco, M. (2019). Understanding urban high school students of color motivation to teach: Validating the FIT-Choice Scale. Urban Education, 54(7), 957–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C. A., & Blom, E. (2017). Diversifying the classroom: Examining the teacher pipeline. Urban Institute. Available online: https://www.urban.org/features/diversifying-classroom-examining-teacher-pipeline (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Mack, F. R., Smith, V. G., & VonMany, N. (2003, January 24–27). African-American honor students’ perceptions of teacher education as a career choice [Paper presentation]. American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education Conference 2003, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marrun, N. A., Plachowski, T. J., Mauldin, D. A. R., & Clark, C. (2021). “Teachers don’t really encourage it”: A critical race theory analysis of high school students’ of color perceptions of the teaching profession. Multicultural Education Review, 13(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccray, A. D., Sindelar, P. T., Kilgore, K. K., & Neal, L. I. (2002). African-American women’s decisions to become teachers: Sociocultural perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(3), 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. S. (1995). The origins of the presumption of black stupidity. Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, (9), 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2024). Data point: Black or African American teachers: Background and school settings in 2017–2018. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

- Noguera, P. A., & Alicea, J. A. (2020). Structural racism and the urban geography of education. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(3), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, A., Gladstone, J., Rosenzweig, E., & Wang, M. T. (2021). Why do I teach? A mixed-methods study of in-service teachers’ motivations, autonomy-supportive instruction, and emotions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A. M., Stephens, H., & Donoghoe, M. (2024). Black wealth is increasing, but so is the racial wealth gap. Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/black-wealth-is-increasing-but-so-is-the-racial-wealth-gap/ (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Redding, C. (2019). A teacher like me: A review of the effect of student–teacher racial/ethnic matching on teacher perceptions of students and student academic and behavioral outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. V., & Rodriguez, L. F. (2015). “A fly in the ointment”: African American male preservice teachers’ experiences with stereotype threat in teacher education. Urban Education, 50(6), 689–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, V. H. (1999). Factors influencing the career choices of African American collegians: Implications for minority teacher recruitment. Journal of Negro Education, 68(3), 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. G., Mack, F. R.-P., & Akyea, S. G. (2004). African-American male honor students’ views of teaching as a career choice. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31(2), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, E. D., Greer, L., Berdie, L., Schwartz, H. L., Woo, A., Doan, S., Lawrence, R. A., Wolfe, R. L., & Gittens, A. D. (2022). Prioritizing strategies to racially diversify the K-12 teacher workforce: Findings from the state of the American teacher and state of the American principal surveys. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-6.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Sullivan, B., Hays, D., & Bennett, N. (2024). Households with a White, non-Hispanic householder were ten times wealthier than those with a Black householder in 2021. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2024/04/wealth-by-race.html (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Taylor, V., Golden, L., & Bak, L. (2021). Structural racism: What can I do as a diabetes care and education specialist? ADCES in Practice, 9(4), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-Choice scale. Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H. M. G., Richardson, P. W., Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Beyer, B., Trautwein, U., & Baumert, J. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FIT-Choice scale. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(6), 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, A. S. (2020). Why mainstream research will not end scientific racism in psychology. Theory & Psychology, 30(3), 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).