Accessibility of Online Information About Student Post-Secondary Physical Health Activities and Initiatives on North American Campuses

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Institution Selection Criteria

2.1.1. Exclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Additional Considerations

2.2. Physical Activity Web Search

2.3. Social Media Search

Data Analysis

3. Results

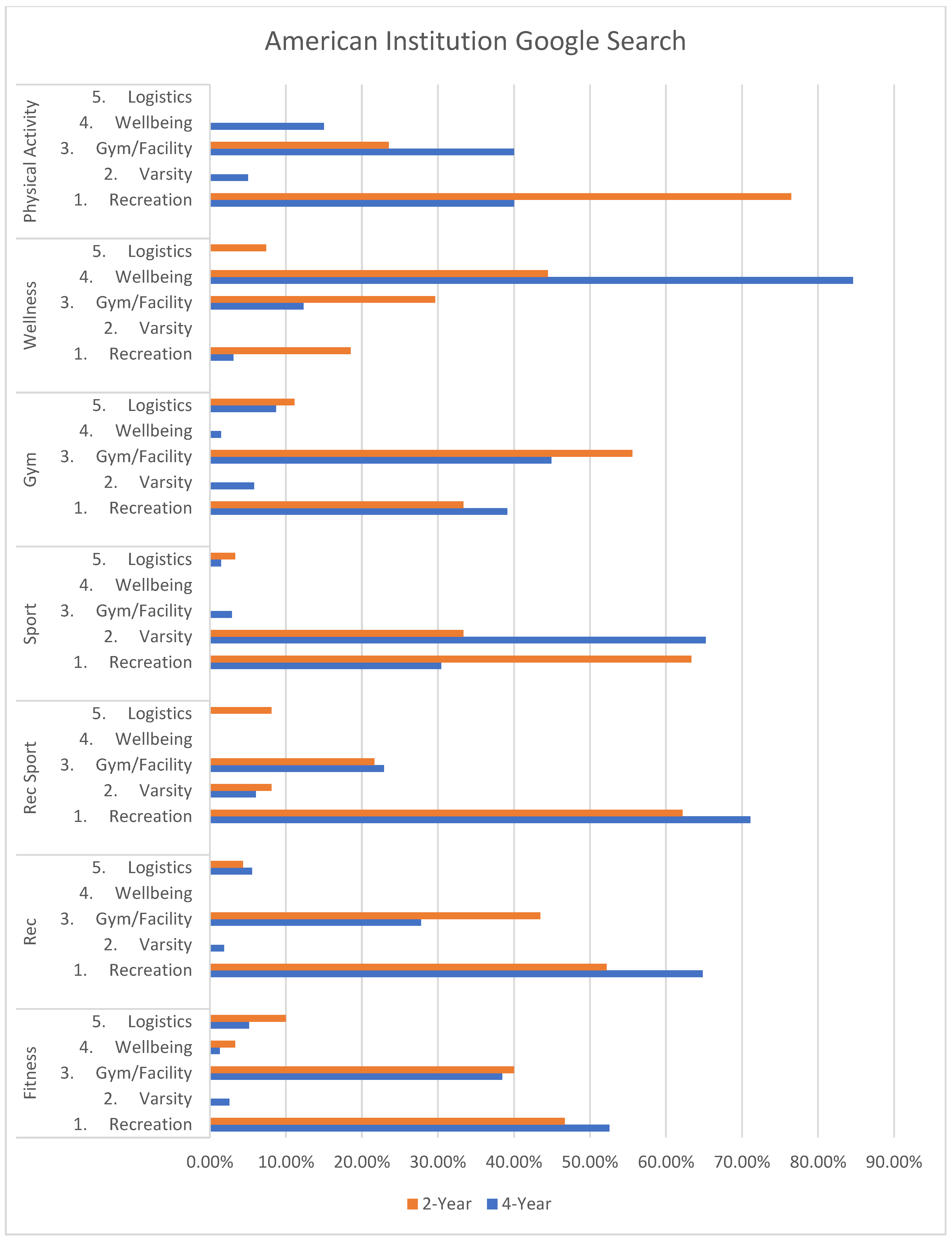

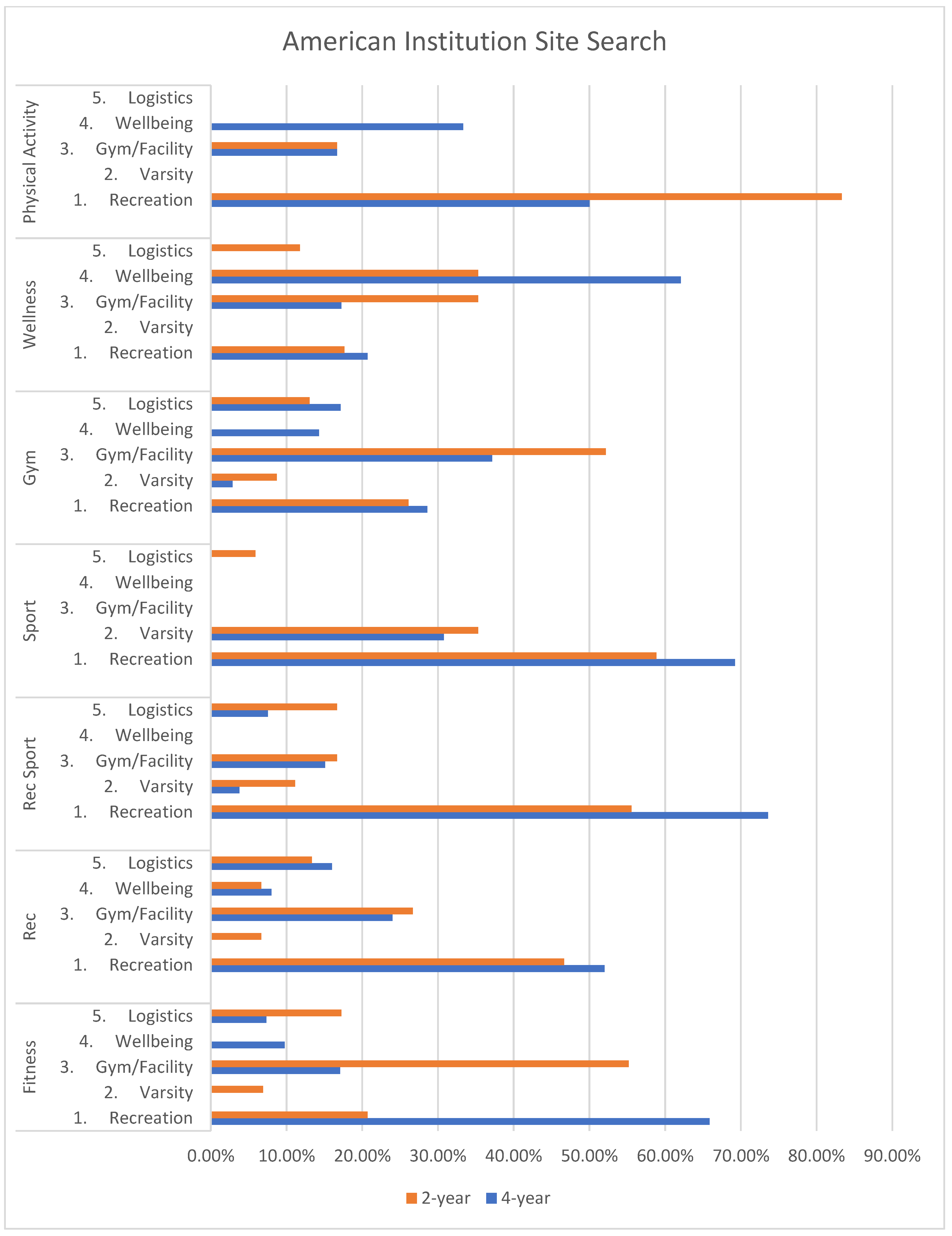

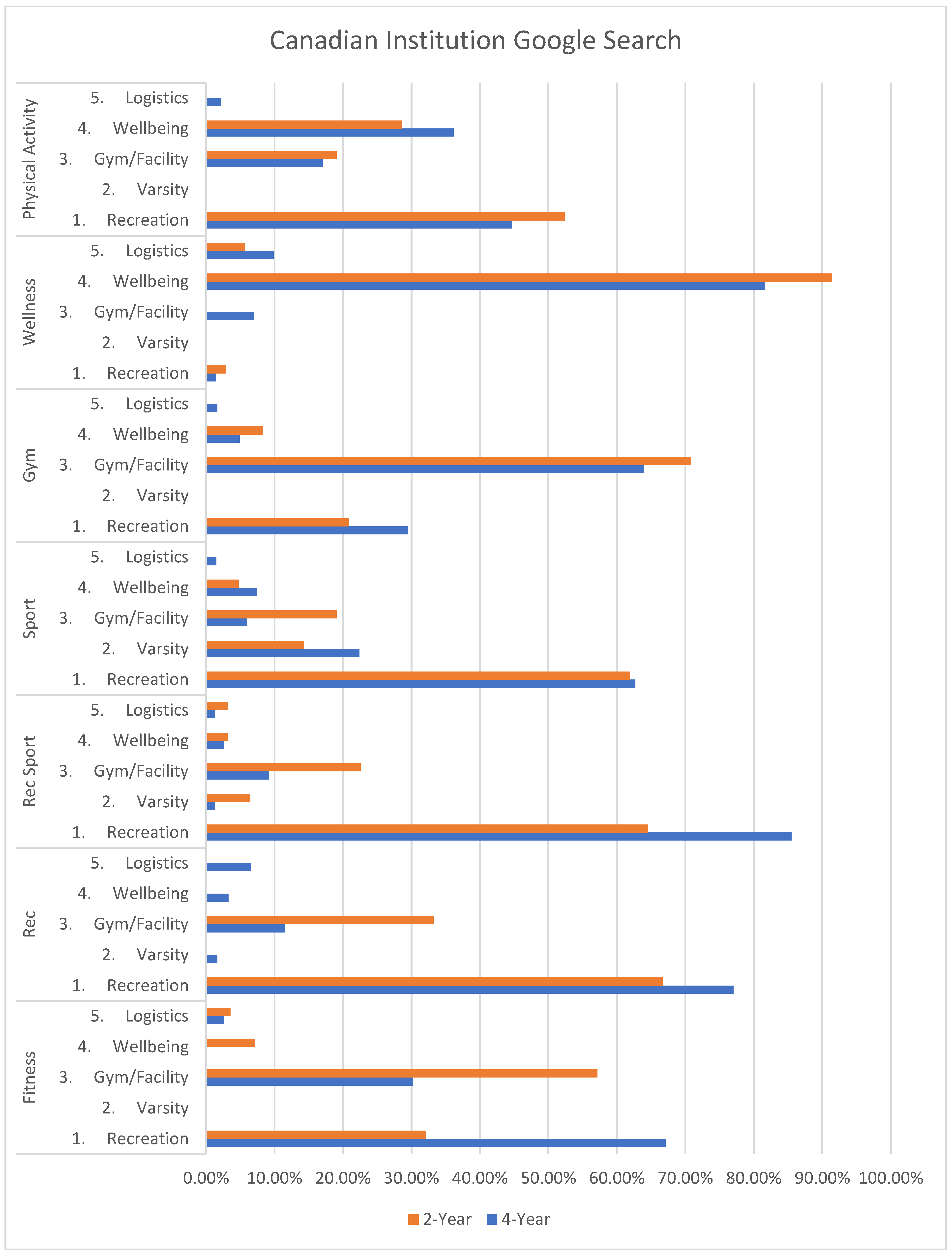

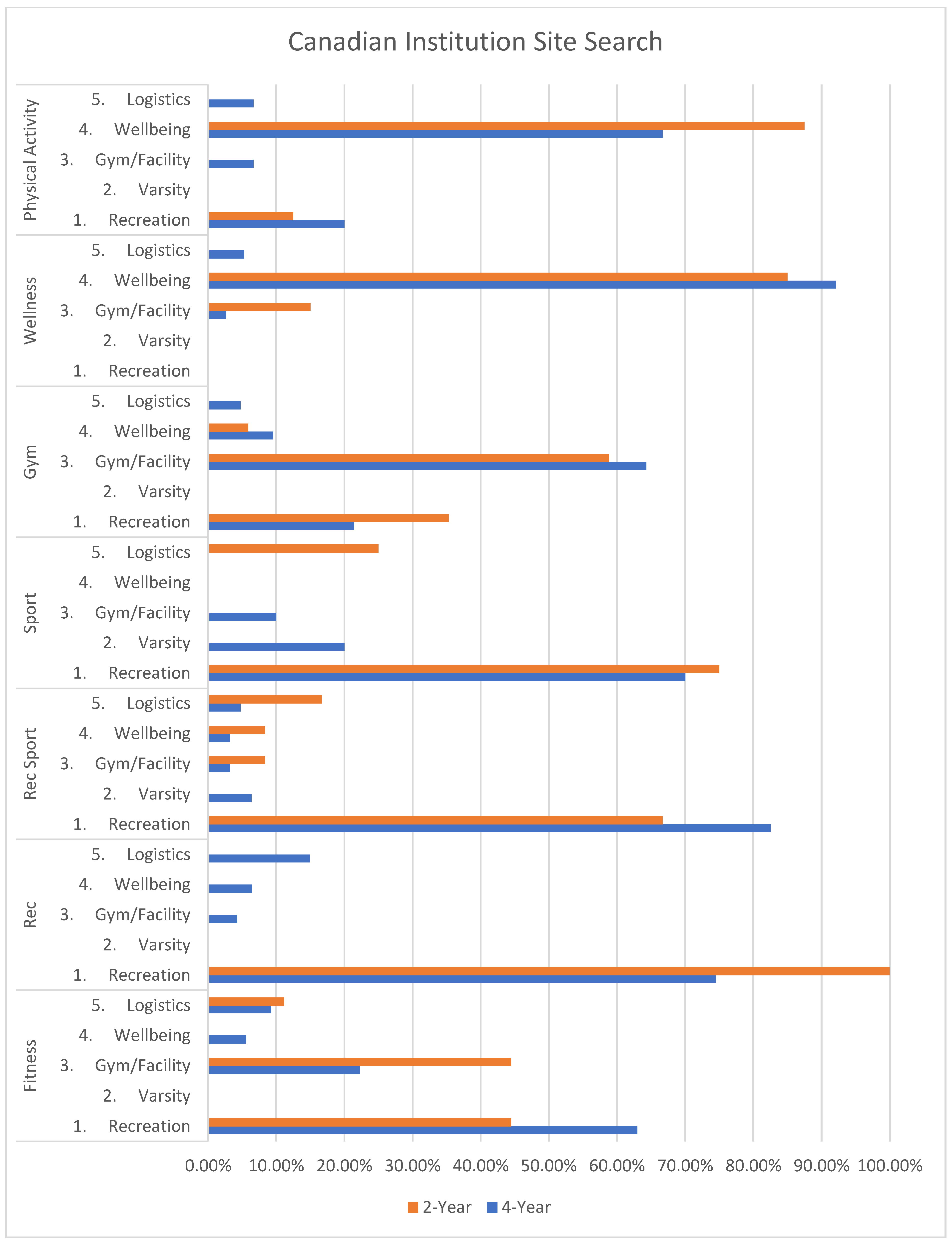

3.1. Web Search

3.1.1. Overall Results

3.1.2. Results by Theme

3.2. Social Media Search

3.2.1. Overall Results

3.2.2. Physical Activity Initiatives

4. Discussion

4.1. General Findings

4.2. Variation by Country

4.3. Variations Between Institutional Sites and Social Media

4.4. Suggestions

4.4.1. Improving Accessibility

4.4.2. Addressing Gaps in Content and Themes

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AFI News. (2023, March 24). Are Canadians just as involved and interested with football as Americans? American Football International. Available online: https://www.americanfootballinternational.com/are-canadians-just-as-involved-and-interested-with-football-as-americans/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Altheide, D. (1996). Qualitative media analysis. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. (2019). American college health association-national college health assessment II: Reference group executive summary spring 2019. American College Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Auxier, B., & Anderson, M. (2021, April 7). Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Avram, E. M. (2015). The importance of online communication in higher education. Network Intelligence Studies, 3(5), 15–21. Available online: https://seaopenresearch.eu/Journals/articles/NIS_5_2.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. M. Y., Faulkner, G. E. J., & Kwan, M. Y. W. (2022). Healthier movement behavior profiles are associated with higher psychological wellbeing among emerging adults attending post-secondary education. Journal of Affective Disorders, 319, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D. M. Y., & Kwan, M. Y. W. (2021). Movement behaviors and mental wellbeing: A cross-sectional isotemporal substitution analysis of Canadian adolescents. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 736587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colleges and Institutes Canada. (2023). Our members. Available online: https://www.collegesinstitutes.ca/colleges-and-institutes-in-your-community/our-members/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S. (n.d.). 6 techniques to effectively implement a campus communication platform. Available online: https://www.owlvc.com/insights-6-techniques-for-campus-communication-platform.php (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Faubert, C. (2009). Tensions and dilemmas experienced by a change agent in a community–university physical activity initiative. Critical Public Health, 19(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M. A., Gorter, J. W., & Boyle, M. H. (2015). Trajectories of depressive symptoms in Canadian emerging adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2322–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, M. M., Gelinas, B. L., & Friesen, L. N. (2015). Mental health literacy in emerging adults in a university setting: Distinctions between symptom awareness and appraisal. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(5), 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudio, J. (2022, April 11). The discrepancy in popularity of American and Canadian college sports. GH360. Available online: https://www.gh360.ca/?p=17298 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2023, September 21). Postsecondary enrolments, by registration status, institution type, status of student in Canada and gender. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710001801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.2&pickMembers%5B1%5D=5.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=7.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=4.1&pickMembers%5B4%5D=6.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2020+%2F+2021&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2020+%2F+2021&referencePeriods=20200101%2C20200101 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Hatfield, D. P., Sharma, S., Bailey, C. P., Bakun, P., Hennessy, E., Simon, C., & Economos, C. D. (2022). Implementation of nutrition and physical activity-related policies and practices on college campuses participating in the healthier campus initiative. Journal of American College Health, 72, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horacek, T. M., White, A. A., Byrd-Bredbenner, C., Reznar, M. M., Olfert, M. D., Morrell, J. S., Koenings, M. M., Brown, O. N., Shelnutt, K. P., Kattelmann, K. K., Greene, G. W., Colby, S. E., & Thompson-Snyder, C. A. (2014). PACES: A physical activity campus environmental supports audit on university campuses. American Journal of Health Promotion, 28(4), e104–e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idowu, O. A., Omoijahe, B., Fawole, H. O., Adeagbo, I., & Akinola, B. I. (2024). Physical activity information-seeking behaviour and barriers in a sample of university undergraduate emerging adults: A cross-sectional survey. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy, 29(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M. Y., Faulkner, G. E., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., & Cairney, J. (2013). Prevalence of health-risk behaviours among Canadian post-secondary students: Descriptive results from the national college health assessment. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloughen, A., Foster, K., Kerley, D., Delgado, C., & Turnell, A. (2016). Physical health and well-being: Experiences and perspectives of young adult mental health consumers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(4), 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milroy, J. J., Wyrick, D. L., Bibeau, D. L., Strack, R. W., & Davis, P. G. (2012). A university system-wide qualitative investigation into student physical activity promotion conducted on college campuses. American Journal of Health Promotion, 26(5), 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J., McGrane, B., White, R. L., & Sweeney, M. R. (2022). Self-Esteem, meaningful experiences and the rocky road—Contexts of physical activity that impact mental health in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021, May). COE—Undergraduate enrollment. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cha (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Digest of education statistics, 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_312.10.asp (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Nietzel, M. T., & Ambrose, C. M. (2024, February 5). Colleges on the brink. Inside Higher Ed. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/02/05/most-colleges-finances-are-biggest-challenge-opinion (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Ori, E. M., & Berry, T. R. (2020). Physical activity information seeking among emerging adults attending university. Journal of American College Health, 70(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2019). The rise of social media. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/rise-of-social-media?ref=tms (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Park, S. Y., Andalibi, N., Zou, Y., Ambulkar, S., & Huh-Yoo, J. (2020). Understanding students’ mental well-being challenges on a university campus: Interview study. JMIR Formative Research, 4(3), e15962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. (2024, January 31). Social media fact sheet. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Statistics Canada. (2024a, February 27). Young people and exposure to harmful online content in 2022. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2024005-eng.htm (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Statistics Canada. (2024b, June 19). Canada’s population clock (real-time model). Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2018005-eng.htm (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Thapar, A., Eyre, O., Patel, V., & Brent, D. (2022). Depression in young people. The Lancet, 400(10352), 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. (2024). U.S. and world population clock. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/popclock/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Universities Canada. (2023). Enrolment by university. Universities Canada. Available online: https://www.univcan.ca/universities/facts-and-stats/enrolment-by-university/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Wang, K., Li, Y., Zhang, T., & Luo, J. (2022). The relationship among college students’ physical exercise, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherson, K. A., Joopally, H., Wunderlich, K., Kwan, M. Y. W., Tomasone, J. R., & Faulkner, G. (2021). Post-secondary students’ adherence to the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for adults: Results from the first deployment of the Canadian campus wellbeing survey (CCWS). Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 41(6), 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerlikaya, Z., & Onay Durdu, P. (2017). Usability of university websites: A systematic review. In Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Design and Development Approaches and Methods (pp. 277–287). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zote, J. (2024). Social media demographics to inform your 2024 strategy. Sprout Social. Available online: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/new-social-media-demographics/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

| Google Search | Institution Search | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Word | Theme | 4-Year | 2-Year | 4-Year | 2-Year | Total | ||||

| R1 * | R2 ** | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | |||

| Fitness | Total Fitting Criteria | 38 | 40 | 15 | 15 | 24 | 17 | 16 | 13 | 178 |

| 1. Recreation | 16 | 25 | 8 | 6 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 88 | |

| a. Homepage | 8 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 27 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |

| c. Activities | 6 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 49 | |

| 2. Varsity | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 18 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 65 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 5. Logistics | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 15 | |

| Rec | Total Fitting Criteria | 33 | 21 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 117 |

| 1. Recreation | 18 | 17 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 67 | |

| a. Homepage | 13 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 35 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 4 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 28 | |

| c. Activities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 2. Varsity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 11 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 35 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| 5. Logistics | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | |

| Rec Sport | Total Fitting Criteria | 47 | 36 | 20 | 17 | 33 | 20 | 10 | 8 | 191 |

| 1. Recreation | 31 | 28 | 12 | 11 | 22 | 17 | 5 | 5 | 131 | |

| a. Homepage | 14 | 15 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 48 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 15 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 14 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 77 | |

| c. Activities | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| 2. Varsity | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 12 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 12 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 32 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5. Logistics | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | |

| Sport | Total Fitting Criteria | 40 | 29 | 14 | 16 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 129 |

| 1. Recreation | 9 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 59 | |

| a. Homepage | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 7 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 39 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| 2. Varsity | 30 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 65 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5. Logistics | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Gym | Total Fitting Criteria | 39 | 30 | 16 | 20 | 26 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 163 |

| 1. Recreation | 13 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 55 | |

| a. Homepage | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 32 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 17 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| 2. Varsity | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 21 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 76 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 5. Logistics | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 19 | |

| Wellness | Total Fitting Criteria | 32 | 33 | 13 | 14 | 19 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 137 |

| 1. Recreation | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 16 | |

| a. Homepage | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 27 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 26 | 29 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 91 | |

| 5. Logistics | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Physical Activity | Total Fitting Criteria | 7 | 13 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 49 |

| 1. Recreation | 1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 29 | |

| a. Homepage | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 5. Logistics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Google Search | Institution Search | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Word | Theme | 4-Year | 2-Year | 4-Year | 2-Year | Total | ||||

| R1 * | R2 ** | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | |||

| Fitness | Total Fitting Criteria | 42 | 34 | 14 | 13 | 32 | 22 | 7 | 2 | 166 |

| 1. Recreation | 23 | 28 | 2 | 7 | 20 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 98 | |

| a. Homepage | 11 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 46 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| c. Activities | 9 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 45 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 18 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 55 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 5. Logistics | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 9 | |

| Rec | Total Fitting Criteria | 35 | 26 | 13 | 7 | 30 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 136 |

| 1. Recreation | 25 | 22 | 9 | 5 | 21 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 104 | |

| a. Homepage | 20 | 17 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 72 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| c. Activities | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 19 | |

| 2. Varsity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| 5. Logistics | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| Rec Sport | Total Fitting Criteria | 38 | 38 | 17 | 14 | 35 | 28 | 11 | 1 | 182 |

| 1. Recreation | 31 | 34 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 22 | 7 | 1 | 145 | |

| a. Homepage | 22 | 22 | 6 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 89 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 34` | |

| c. Activities | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 22 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 18 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | |

| 5. Logistics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | |

| Sport | Total Fitting Criteria | 36 | 31 | 14 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 111 |

| 1. Recreation | 22 | 20 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 72 | |

| a. Homepage | 12 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 38 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 27 | |

| c. Activities | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| 2. Varsity | 9 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| 5. Logistics | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Gym | Total Fitting Criteria | 40 | 21 | 16 | 8 | 33 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 145 |

| Recreation | 11 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 38 | |

| a. Homepage | 10 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 31 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Varsity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gym/Facility | 27 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 22 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 93 | |

| Wellbeing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 | |

| Logistics | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Wellness | Total Fitting Criteria | 38 | 33 | 20 | 15 | 28 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 164 |

| 1. Recreation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| a. Homepage | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| c. Activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 28 | 30 | 19 | 13 | 25 | 10 | 13 | 4 | 140 | |

| 5. Logistics | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| Physical Activity | Total Fitting Criteria | 22 | 25 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 91 |

| 1. Recreation | 8 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 36 | |

| a. Homepage | 5 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 26 | |

| b. Sports/Clubs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| c. Activities | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| 2. Varsity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. Gym/Facility | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| 4. Wellbeing | 8 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 40 | |

| 5. Logistics | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

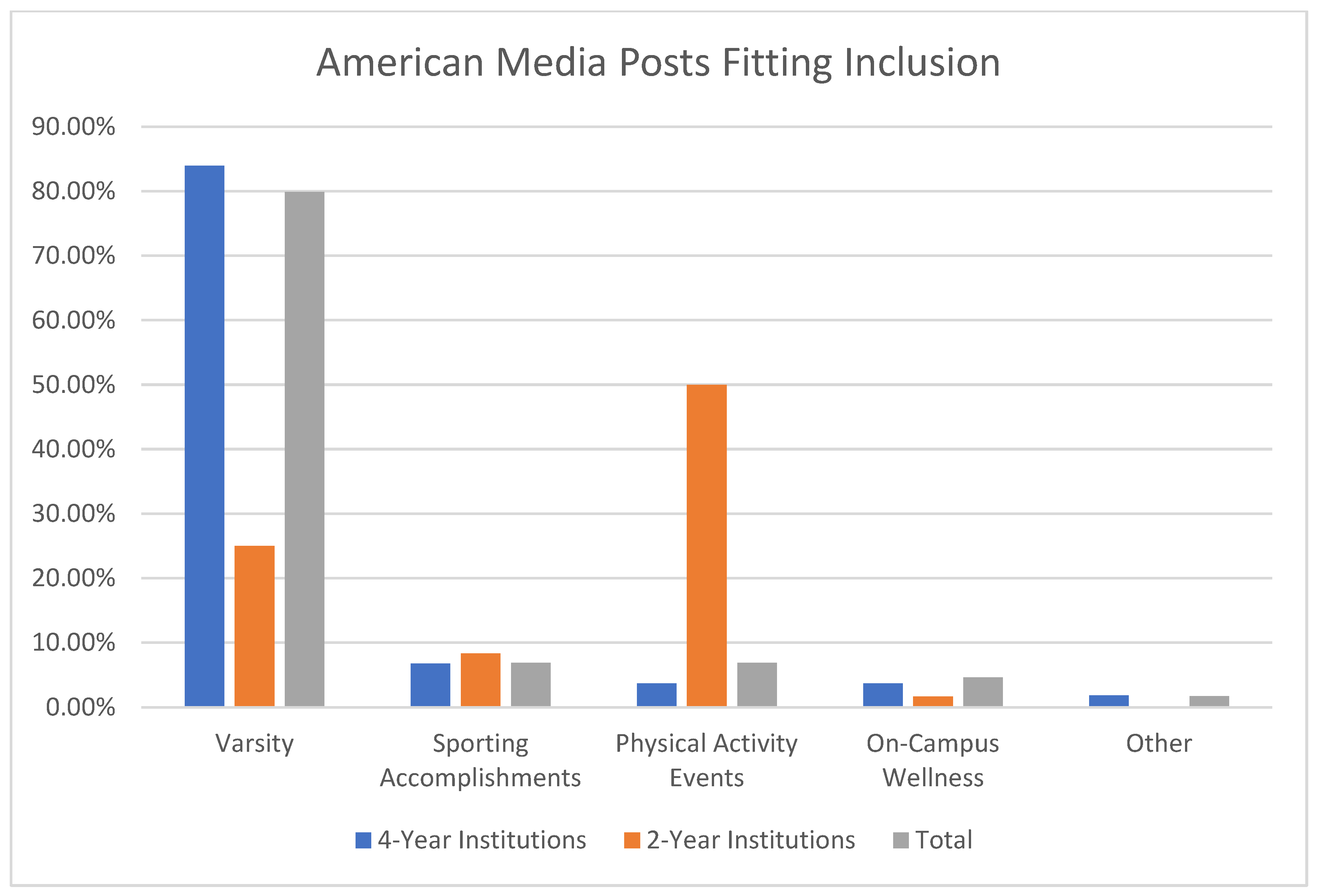

| Theme | 4-Year Institutions | 2-Year Institutions | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Posts in 1 Year | 2656 | 1530 | 4186 |

| Posts Fitting Inclusion Criteria | 162 | 12 | 174 |

| 1. Varsity | 136 | 3 | 139 |

| 2. Sporting Accomplishments | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| 3. Physical Activity Events | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 4. On-Campus Wellness | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| 5. Other | 3 | 0 | 3 |

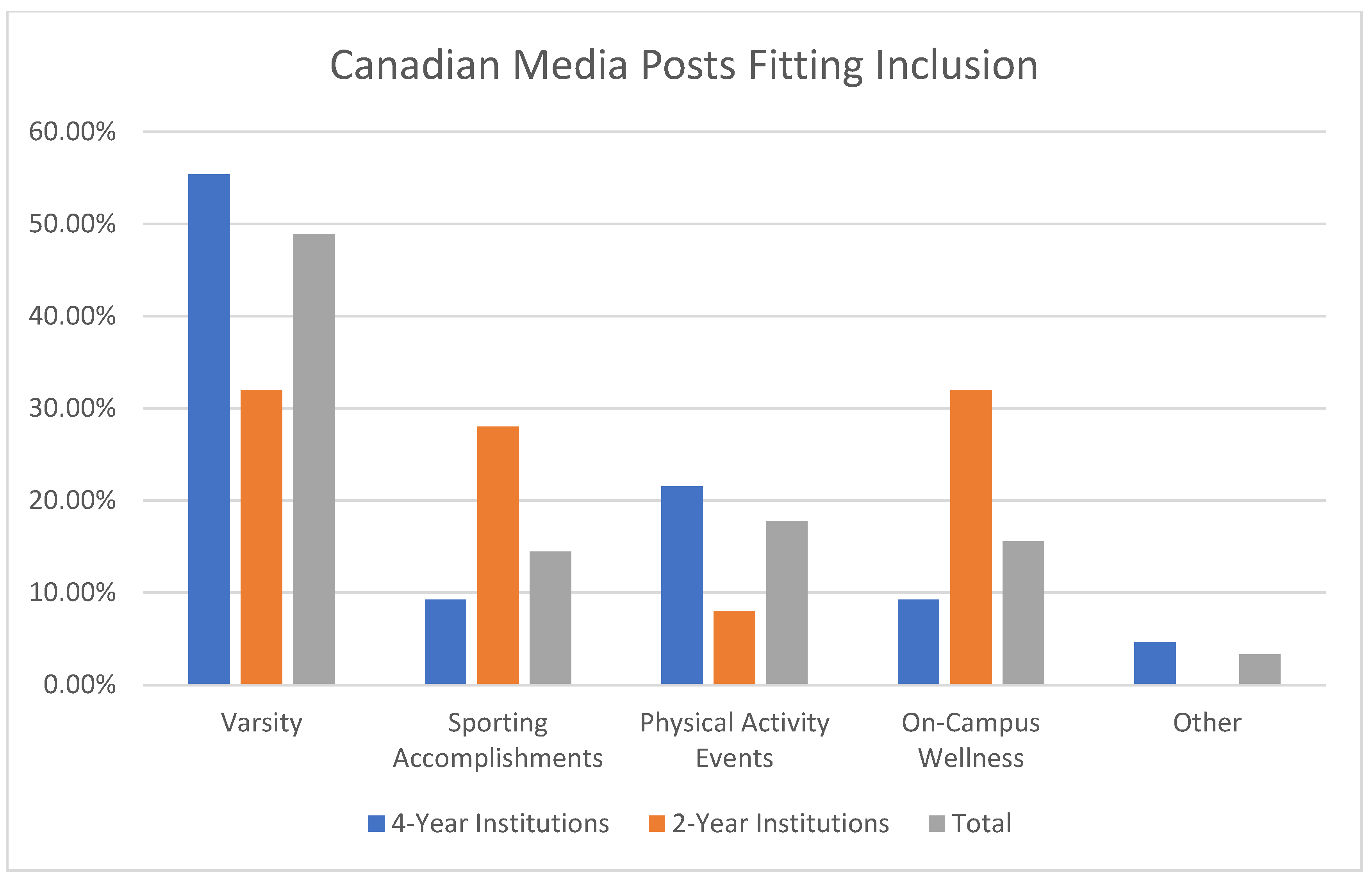

| Theme | 4-Year Institutions | 2-Year Institutions | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Posts in 1 Year | 1880 | 1390 | 3270 |

| Posts Fitting Inclusion Criteria | 65 | 25 | 90 |

| 1. Varsity | 36 | 8 | 44 |

| 2. Sporting Accomplishments | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| 3. Physical Activity Events | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| 4. On-Campus Wellness | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| 5. Other | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murray, J.K.; Knudson, S. Accessibility of Online Information About Student Post-Secondary Physical Health Activities and Initiatives on North American Campuses. Youth 2025, 5, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030085

Murray JK, Knudson S. Accessibility of Online Information About Student Post-Secondary Physical Health Activities and Initiatives on North American Campuses. Youth. 2025; 5(3):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030085

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurray, Jonah Kynan, and Sarah Knudson. 2025. "Accessibility of Online Information About Student Post-Secondary Physical Health Activities and Initiatives on North American Campuses" Youth 5, no. 3: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030085

APA StyleMurray, J. K., & Knudson, S. (2025). Accessibility of Online Information About Student Post-Secondary Physical Health Activities and Initiatives on North American Campuses. Youth, 5(3), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030085