Why Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Programs Matter: Results from a Participatory Evaluation Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Co-Authorship

3. Background

3.1. Sexual Violence Prevalence Among Adolescents

3.2. Sexual Violence Prevention Approaches

3.3. Youth-Led Violence Prevention Programming

3.4. Sexual Violence in Wisconsin, United States

4. Project Context

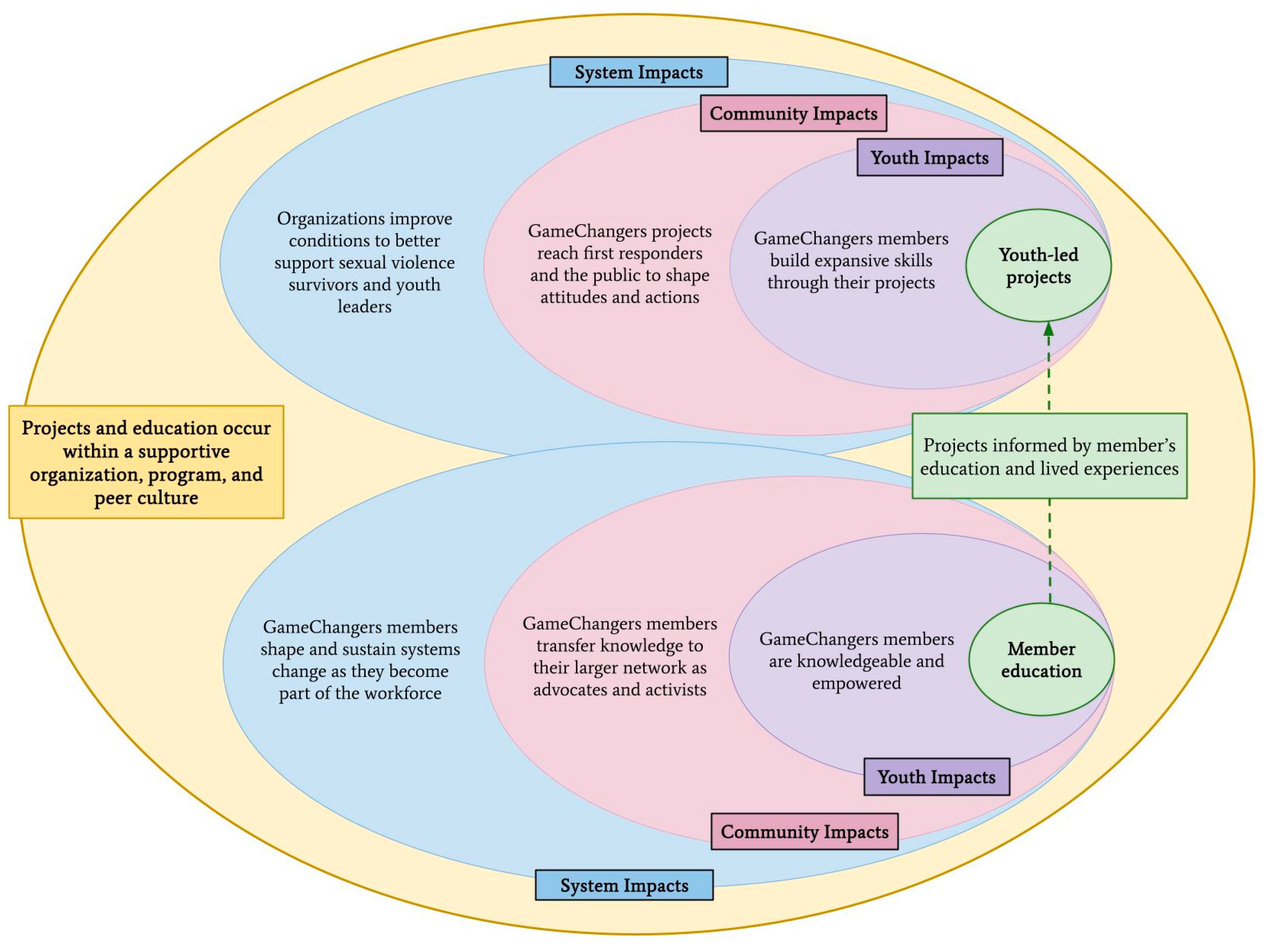

GameChangers Evaluation Project

5. Evaluation Methods

5.1. Evaluation Design

5.2. Participants

5.3. Procedure

6. Findings

6.1. Member Education

“I feel like GameChangers helped me not hide away from myself and be able to speak my truth and advocate for myself and be able to just be myself without fear of other people judging me”.

“We were well equipped with an understanding and resources so that we ourselves could look out for anybody that needed help. So, I think on a personal level, it gave us things that we could use if we ever needed them”.

“Things that might feel [like] the initial respectful thing to ask, might not actually be what that person is wanting in that moment. I’ve learned a lot of strategies and ways that empathy can look different to different people in different situations”.

“There’s so many intersections between social justice and health, and social justice and law and all sorts of different fields and academia and teaching… I think GameChangers has definitely shown me the need to have advocates in all different fields”.

“I definitely left more empowered to put my best foot forward in professional settings, to advocate for others. Working with a lot of people who come from different backgrounds, who had different skills to bring to the table, different values, [GameChangers] made me much more open, and a person that was willing to also step back”.

“By forming that solidarity from a fairly young age and getting involved with activism, GameChangers is creating new leaders and instilling all these different ideals in young people that will serve on a personal level into adulthood but will also make a more responsible and empathetic community as we all get older”.

6.2. Youth-Led Projects

“A lot of what GameChangers does as its core work is seeking to understand how we can make a world that isn’t built around violence and oppression”.

“GameChangers made me more confident in my own skills because we got so many opportunities to show off our expertise”.

“I felt like I was going to impact the educators and then later down the line, I was going to be able to affect the students. I felt like I was going make a long-term goal and I was able to prevent sexual violence”.

6.3. Supportive Settings Matter

“There’s a central focus on fostering change and having youth be at the center of that, and centering youth voice and centering the voices of communities who have been historically underrepresented and devalued, but then also the communities who are also currently going through that”.

“Especially with the aspect of being educated by different types of people and working together in the projects, it was really important to build trust and build community and get to know each other”.

7. Strategies for Youth Programs

7.1. Accessibility and Accommodating Needs

7.2. Platforming Youth Voice and Autonomy

7.3. Creating a Meaningful Program and Culture

8. Future Directions for Program Evaluation

9. Conclusions

“GameChangers literally changed my whole mind and direction of my life. I realized that I just wanted to continue activism and helping our underserved communities”.—Aspen

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A. GameChangers Evaluation Project Interview Protocol

- To get started, can you tell me about why you got involved with GameChangers?

- Follow-up: How long have you been involved? How’d you hear/find out about GameChangers?

- Describe how GameChangers is different or similar to other groups, jobs, or organizations you’ve participated in.

- What do/did you enjoy most about being in GameChangers?

- Probe: Working alongside the other students, facilitators/adult leaders

- Probe: Experiences with mentorship

- Probe: The different projects!

- What’s a highlight of your time in GameChangers/so far?

- What kinds of tools, skills, knowledge have you gained?

- Probe: Supporting a friend, having difficult conversations, how to be safe at demonstrations

- Probe: Knowledge about power, intersectionality, oppression

- Probe: Practicing self-care, social media, professional skills

- How have you changed since working with GameChangers and the RCC?

- Probe: Worldview shift

- Probe: Skills, confidence, friendships

- What would you tell a classmate about GameChangers, who knows nothing about it?

- Prevention is defined as any individual or collective action that includes behavioral and social interventions to protect both individuals and entire populations from harm.

- How do you think your experiences in GameChangers align with that definition?

- Probe: Education, bystander intervention, crisis support

References

- Banyard, V., Edwards, K. M., Waterman, E. A., Kollar, L. M. M., Jones, L. M., & Mitchell, K. J. (2023). Exposure to a youth-led sexual violence prevention program among adolescents: The impact of engagement. Psychology of Violence, 12(6), 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, K. C., DeGue, S., Jones, K., Freire, K., Dills, J., Smith, S. G., & Raiford, J. L. (2016). STOP SV: A technical package to prevent sexual violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A., Agha, A., Demyan, A., & Beatriz, E. (2016). Examining criminal justice responses to and help-seeking patterns of sexual violence survivors with disabilities. National Institute of Justice. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/examining-criminal-justice-responses-and-help-seeking-patterns (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Chandra-Mouli, V., Lane, C., & Wong, S. (2015). What does not work in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A review of evidence on interventions commonly accepted as best practices. Global Health: Science and Practice, 3(3), 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, J., & Evans, R. (2008). Reflections on practical approaches to involving children and young people in the data analysis process. Children & Society, 22, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cody, C. (2017). ‘We have personal experiences to share, it makes it real’: Young people’s views on their role in sexual violence prevention efforts. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, R. W., Mair, C., Miller, E., Blosnich, J. R., Matthews, D. D., & McCauley, H. L. (2017). Prevalence of past-year sexual assault victimization among undergraduate students: Exploring differences by and intersections of gender identity, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity. Prevention Science, 18, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 46(6), 1241–1299. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039 (accessed on 21 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A Meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K. M., & Banyard, V. L. (2018). Preventing sexual violence among adolescents and young adults. In D. A. Wolfe, & J. R. Temple (Eds.), Adolescent dating violence: Theory, research, and prevention (pp. 415–435). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, K. M., Banyard, V. L., Waterman, E. A., Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Kollar, L. M. M., Hopfauf, S., & Simon, B. (2022). Evaluating the impact of a youth-led sexual violence prevention program: Youth leadership retreat outcomes. Prevention Science, 23(8), 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K. M., Jones, L., Mitchell, K., Hagler, M., & Roberts, L. (2016). Building on youth’s strengths: A call to include adolescents in developing, implementing, and evaluating violence prevention programs. Psychology of Violence, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M., Ullman, C., Blackwell, A., Hill, A., & Contreras, M. (2018). What works to prevent adolescent intimate partner and sexual violence? A global review of best practices. In D. A. Wolfe, & J. R. Temple (Eds.), Adolescent dating violence: Theory, research, and prevention (pp. 381–414). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, J., & Weishart, J. (2023). How discriminatory censorship laws imperil public education (pp. 1–44). National Education Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Flasher, J. (1978). Adultism. Adolescence, 13(51), 517–523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flicker, S., & Guta, A. (2008). Ethical approaches to adolescent participation in sexual health research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillard, A., & Witt, P. (2008). Recruitment and retention in youth programs. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 26(2), 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, S. (2021, October 13). East high students walk out to support victim in alleged sexual assault. The Cap Times. Available online: https://captimes.com/news/local/education/local_schools/east-high-students-walk-out-to-support-victim-in-alleged-sexual-assault/article_d83dccaa-373a-5e30-8e80-eb9d669685a0.html (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Hart, R. A. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. UNICEF Innocenti Essays (No. 4). UNICEF International Child Development Centre. ISBN 88-85401-05-8. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie, D. L., Farhat, T., Brooks-Russell, A., Wang, J., Barbieri, B., & Iannotti, R. J. (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, R. (2023). Let’s talk about sex: Requiring comprehensive sex education to address teen dating violence in Kansas. Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy, 33(1), 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm, L. L. (2024). Youth engagement in sexual violence prevention programs and research: A systematic review. Sexes, 5(3), 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, D., & Malin, J. R. (2023). Demobilizing knowledge in American schools: Censoring critical perspectives. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, C., Grundhoefer, S., & Arrillaga, E. S. (2024). State of nonprofits 2024: What funders need to know. Center for Effective Philanthropy. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L. M., & Wagner, E. (2013). Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuelzer, L. (2023). Education in the age of censorship. Journal of Thought, 57(3/4), 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lamerias-Fernández, M., Martinez-Roman, R., Carrera-Fernandez, M. V., & Rodriguez-Castro, Y. (2021). Sex education in the spotlight: What is working? A Systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., Stark, A. K., O’Riordan, M. A., & Lazebnik, R. (2015). Awareness of a rape crisis center and knowledge about sexual violence among high school adolescents. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 28(1), 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L., Jamal, A., & Ikeda, J. (2020). Extending youth voices in a participatory thematic analysis approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920934614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorde, A. (1988). A burst of light. Firebrand Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J. K., Dworkin, J., Borden, L. M., Perkins, D., & Russell, S. T. (2016). Youth motivations for program participation. Journal of Youth Development: Bridging Research and Practice, 11(3), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, D. A., Jones, R., & Cramer, E. P. (2015). An evaluation of a school-based, peer-facilitated, healthy relationship program for at-risk adolescents. Children & Schools, 37(2), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, Q. M., Veliz, P. T., Kusunoki, Y., Stein, S. F., & Boyd, C. J. (2018). Adolescent sexual violence: Prevalence, adolescent risks, and violence characteristics. Preventive Medicine, 116, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E. J. (2017). Youth-led participatory action research: Overview and potential for enhancing adolescent development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(3), 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomazal, R., Malecki, K. M., McCulley, L., Stafford, N., Schowalter, M., & Schultz, A. (2023). Changes in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Wisconsin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J. L., & Tiffany, J. S. (2006). Engaging youth in participatory research and evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 12, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, L., & Ross, B. (2023, February 15). Records show new details in Middleton High football program harassment investigation. Fox 47. Available online: https://fox47.com/news/local/records-show-new-details-in-middleton-high-football-program-harassment-investigation (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Roach, E. (2020, February 19). What happens next? A legal look ahead at Middleton High School’s ongoing nude photograph investigation. The Cardinal Chronicle. Available online: https://mhscardinalchronicle.com/2495/news/what-happens-next-a-legal-look-ahead-at-middleton-high-schools-ongoing-nude-photograph-investigation/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2016). Evaluating youth development programs: Progress and promise. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIECUS. (2024). Detailed insights on U.S. sex education policies. SIECUS. Available online: https://siecus.org/siecus-state-profiles (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M. J., & Chen, J. (2018). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief–updated release. Center for Disease Control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Struthers, K., Parmenter, N., & Tibury, C. (2019). Young people as agents of change in preventing violence against women. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety. Available online: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1797899170 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Teixeira, S., Augsberger, A., Richards-Schuster, K., & Sprague Martinez, L. (2021). Participatory research approaches with youth: Ethics, engagement, and meaningful action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(1–2), 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Maryland Collaborative. (2016). Sexual assault and alcohol: What the research evidence tells us. Center on Young Adult Health and Development. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Attorney’s Office. (2021, October 21). Former Madison high school teacher sentenced to 12 years for secretly filming students. United States Attorney’s Office, Western District of Wisconsin. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdwi/pr/former-madison-high-school-teacher-sentenced-12-years-secretly-filming-students (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Villa-Torres, L., & Svanemyr, J. (2014). Ensuring youth’s right to participation and promotion of youth leadership in the development of sexual and reproductive health policies and programs. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, N. (2021, October 14). District responds to Madison East walkout; Thanks students for speaking out. WMTV 15 News. Available online: https://www.wmtv15news.com/2021/10/14/district-responds-madison-east-walkout-thanks-students-speaking-out/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2019). Sexual violence prevention needs assessment report (2018–2019). Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Available online: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02445.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2020). Sexual violence in Wisconsin [Fact sheet]. Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Available online: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p02763.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Wisconsin State Legislature. (2024). Human growth and development instruction (Statute #118.019). Available online: https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/118/019 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Zukoski, A. P., & Bosserman, C. (2018). Essentials of participatory evaluation. In Collaborative, participatory, and empowerment evaluation (pp. 48–56). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

| Years Participated in GameChangers | n |

|---|---|

| One year | 3 |

| Two years | 5 |

| Three years | 2 |

| Four years | 4 |

| Phase 1: Data Collection | 14 youth experts | Current, returning members or alumni of GameChangers |

| Phase 2: Data Analysis | 8 youth evaluators | Pulled from youth expert pool; all alumni |

| Phase 3: Dissemination | 10 youth evaluators | Included evaluators from Phase 2 and four additional/new alumni of GameChangers |

| Article Preparation and Writing | 6 youth evaluators | All authors contributed data as youth experts and were engaged as evaluators in Phases 2 and 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hjelm, L.L.; Rudykh, D.; Wang, K.; Dyer, A.; Ni, C.; Herrmann, S.; Headley, O. Why Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Programs Matter: Results from a Participatory Evaluation Project. Youth 2025, 5, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030087

Hjelm LL, Rudykh D, Wang K, Dyer A, Ni C, Herrmann S, Headley O. Why Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Programs Matter: Results from a Participatory Evaluation Project. Youth. 2025; 5(3):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030087

Chicago/Turabian StyleHjelm, Linnea L., Daria Rudykh, Kaitlynn Wang, Amelia Dyer, Crystal Ni, Summer Herrmann, and Olivia Headley. 2025. "Why Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Programs Matter: Results from a Participatory Evaluation Project" Youth 5, no. 3: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030087

APA StyleHjelm, L. L., Rudykh, D., Wang, K., Dyer, A., Ni, C., Herrmann, S., & Headley, O. (2025). Why Youth-Led Sexual Violence Prevention Programs Matter: Results from a Participatory Evaluation Project. Youth, 5(3), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030087