1. Introduction

This article extends a key finding introduced in a previous publication using the same data set: creating safe cultural spaces to enable ethnic youths to construct, explore, navigate, and balance their multiple cultural identities (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). Two groups of youths (18–35 years) participated in the study: those born in Aotearoa–New Zealand (ANZ) and those born in Africa and who migrated to ANZ. They both shared their challenges and successes in navigating multiple cultural identities. Cultural identity is defined in this work as the significant ways a person or group defines oneself or is defined by others as connected to culture (characterised by common ancestry, traditions, beliefs, values, practices, and languages) (

Hall, 2014). This working definition of cultural identity stems from a psychosocial perspective that argues that cultural identity is important because it confers a sense of personhood, self-definition, and belonging (

Hall, 1994). Cultural identity is individual and collective (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024).

The African-descent youth, also referred to in this paper as African heritage youth living in ANZ, strongly desired to integrate all aspects of their cultures, particularly their

African-ness and

Kiwi-ness.

African-ness is defined in the study as identifying with being from an African country by birth or by their parent/caregiver being born there and belonging to an African cultural/ethnic group. Most of these youth constructed their

African-ness through the roots and routes theory, particularly transnational socialisation (

Levitt, 2009). Considering the many debates around what makes someone a

real Kiwi and the author’s commitment to honouring Māori as tangata whenua, the perception adopted is that a youth is a

Kiwi if they call ANZ home (

Wood, 2022). The uprooting and regroundings concepts explain how these youth construct their

Kiwi cultural identity, which is hybrid, hyphenated, in-between, or third space (

Mapedzahama & Kwansah-Aidoo, 2010;

Mar-Rwoth, 2023;

Omar, 2016;

Sulyman, 2014). Most youth in the study wanted to be able to choose their cultural identity, including having variations and oscillating between their multiple cultural identities. For instance, some youths wanted to identify only as African, some as Kiwi, and others as both. However, the findings showed this was complicated and challenging for most youth, and more so for youth who migrated at a young age (formative years) and those who are

visibly different. Youth who were dark skinned, for instance, mentioned being automatically identified by others as African without being asked. Dominant othering discourses about migrants often negate their plurality of experiences and histories by either forcing them to choose between cultural identities or choosing for them based on visible attributes such as accent, skin colour, or religion (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). Additionally, many migrant youths experience cultural identity fatigue from having to constantly justify claims of belonging or being forced to represent Africa when they may only have an

imaginary relationship with their African heritage (

K. Kebede, 2017;

Mapedzahama & Kwansah-Aidoo, 2010;

Omar, 2016). Simultaneously, while transnational socialisation is beneficial, it poses some challenges, such as youth being forced to embrace one culture or situations where values or practices between cultures are competing or conflicting. The youths reported that this may often result in temporary or permanent cultural confusion or exclusion from competing cultures (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). It can sometimes cause pressure and challenges for youth in domains where decisions may be made by weighing cultural expectations, such as education and career choices (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023).

The reality for these youths is that their African origins or heritage cannot be erased or changed. ANZ is home by birth or socialisation. Therefore,

Kiwi-ness constitutes who they are, as

Hall (

1994) explains, since history (of immigration) has intervened. Yet their lived experiences show an obliteration of these multiple identities, which, in turn, invokes unsureness about place and belonging, and this can become a barrier to full participation in critical domains such as education and employment (

Sharma et al., 2025). Negative experiences impact their health and well-being in general (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Sharma et al., 2025). Against this background, the youth proposed the idea and practice of creating safe cultural spaces as a holistic care model. The following section contextualises this model of care in extant research.

1.1. Experiences of African-Heritage Youth in ANZ: Context

Immigration has changed the population composition of migrant-receiving countries, for instance, by increasing ethnic diversity (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Ministry of Ethnic Communities, 2025b). The changing demography and cultural heterogeneity have drawn attention to the experiences of ethnic minority groups and, especially within these groups, those deemed vulnerable, such as ethnic youth (

Sharma et al., 2025). Their ethnic minority status has been identified as a notable marker of social disadvantage (

Chile, 2002;

S. S. Kebede, 2010;

Ministry of Youth Development, 2023;

R. Simon-Kumar et al., 2022). In almost all high migrant-receiving countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, and Canada, evidence shows that overseas-born youth and youth born in the country and of migrant descent have higher social exclusion rates than native-born youth (

European Union, 2015;

K. Kebede, 2017;

Sulyman, 2014). Often represented as ethnicity, cultural identity intersects with other multiple social identities, determining health and well-being experiences and outcomes (

N. Simon-Kumar, 2023;

R. Simon-Kumar et al., 2022). Most of the literature on this topic is drawn from the United States, North America, and Europe, which have the largest migrant-receiving countries (

European Union, 2015). However, attention to the experiences of migrant youth, particularly African heritage youth, is also growing in Australasia. Existing studies show that, for these youth, blackness and black body racism intersect with their already minority status, impacting their daily lives (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Edwards et al., 2010;

Gatwiri & Anderson, 2021;

Helm et al., 2019;

Robbins et al., 2017;

Tualaulelei & Taylor-Leech, 2021;

Ward et al., 2010). For instance, a qualitative study with 44 African-heritage youths living in Australia demonstrates how the pervasive culture of racial othering impacts the young people’s well-being, hindering their ability to participate in public spheres without fear and shame and feeling a sense of belonging to the places where they live (

Molla, 2023).

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024) also highlighted the experiences of youth of African descent in ANZ who were navigating multiple identities. While these experiences may be shared by other population groups within migrant communities, it is accentuated for ethnic youth who undergo acculturative tasks alongside normative youth developmental tasks (

Phinney, 2013;

Sharma et al., 2025;

Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

Therefore, it is not surprising to see growing research and evidence pointing to and advocating for culturally informed approaches to addressing challenges facing ethnic youth. In this context, the notion of safe cultural spaces is not new. It is often embedded in the

cultural safety framework, which, in human services delivery, particularly healthcare settings, emerged in response to culturally unsafe practices, defined as any action that diminishes, demeans, and disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual or a group (

Brascoupé & Waters, 2009;

Humpage, 2009). In ANZ, for instance, research with ethnic and racialised youth (often defined as the youth of African, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American backgrounds) is growing but still limited (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Sharma et al., 2025). As observed by studies such as those by

Sharma et al. (

2025) and

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024), there is still a limited understanding of the lived experiences of ethnic youth. The available (limited) data have largely been drawn from large population-based surveys where all the ethnicities are grouped as a homogenous group, and the focus tends to be on the effects of racism on health outcomes (

Sharma et al., 2025).

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024) reflected on the implications of this, such as that experiences unique to specific ethnic sub-groups are often missed and, therefore, not considered in policy-making and care models. Notably, specific models of care for these youth, such as creating safe cultural spaces, are still an underexplored topic.

1.2. Why Is There a Need for Safe Cultural Spaces?

Care for African-decent youth living in ANZ has mostly been explored within overarching themes discussing cultural identity as a factor determining place and belonging (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023;

Tuwe, 2018), cultural identity and experiences of racism and discrimination (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Nakhid, 2017;

Sharma et al., 2025;

R. Simon-Kumar et al., 2022;

Williams, 2022), or in the context of advocating for culturally appropriate support services (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Mar-Rwoth, 2023). Many community-based organisations offering services to African-descent youth across Aotearoa have specific programmes, activities, and, sometimes, physical spaces specific to this population group (

Ministry of Ethnic Communities, 2025a). In many ways, these could be considered safe cultural spaces (

Chubb et al., 2024). However, no study has examined why such spaces warrant consideration, their underlying principles and benefits, or what they could look like as a separate model of care for youth. This paper fills this gap and offers a youth perspective.

The notion of

safe spaces has been advanced in many contexts with many definitions (

Bustamante Duarte et al., 2021). Historically, some trace it to the 1970s movements when many marginalised groups rose against forms of discrimination, hatred, harassment, and colonisation. In these contexts, safe spaces were physical meeting places where like-minded people could meet and share experiences in an environment free from harm (

Flensner & Von der Lippe, 2019). In recent years, the term has increasingly been used in education settings (

Conteh & Brock, 2011), again focusing on minority learners. Places where they can “perform their identities…feel a sense of belonging…and can successfully learn” (

Tualaulelei & Taylor-Leech, 2021, p. 141). A comprehensive discussion of the historical background and how it applies in different contexts is beyond the scope of this section. However, this section reaffirms that the historical background of the concept is to protect marginalised groups from oppression and offer a safe space (

Anderson, 2021;

Flensner & Von der Lippe, 2019).

Fairbairn-Dunlop (

2015) rightly notes that safe spaces are more than just warm and fuzzy. Priority is given to intentional planning to ensure these spaces connect and support participants’ growth and development of further skills and knowledge bases, enabling them to excel (

Fairbairn-Dunlop, 2015).

In the context of immigration, some studies have explored the notion of safe cultural spaces while discussing the complex interplay between cultural identity and psychosocial well-being issues. Primarily, these studies reveal a strong correlation between building a strong cultural identity and positive well-being outcomes (

Edwards et al., 2010;

Helm et al., 2019;

Rivas-Drake et al., 2014;

Sharma et al., 2025;

Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). In ANZ, the notion is more developed in studies about working with Pacific youth than with ethnic youth. Somewhat similar to African-descent youth, Pacifica youth, who are culturally diverse, navigate unique issues and needs due to migration experiences, including navigating multiple cultural identities, discrimination, and disconnection from their communities due to cultural identity struggles (

Chubb et al., 2024;

Ministry of Youth Development, 2023). Therefore, findings from these studies could be contextually transferable. For instance, a study with 1063 Pacific youth and their mothers exploring the risks of involvement in risky behaviours such as gambling and gang involvement found a positive relationship between a strong cultural heritage and low engagement in risky behaviours (

Bellringer et al., 2022). Safe cultural spaces are necessary for constructing and nurturing such strong cultural identities (

Rimoni, 2017;

Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). A similar study, an extensive literature review examining how culturally safe spaces can be created for Pacifica youth, highlighted that these spaces go beyond physical environments to encompass emotional and psychological aspects (

Chubb et al., 2024). They are envisioned to foster environments where these youth feel a sense of inclusion and belonging because they are protected from judgement, harm, and discrimination. Building or providing a space where youth can construct their identity, build positive relationships, and foster connectedness is foundational to culturally safe spaces. Citing several examples of such culturally safe spaces,

Chubb et al. (

2024) concluded that they can be a protective factor for Pacific youth, providing coping resources that mitigate negative experiences, as shown in a survey with 267 Pacific people who reported that a strong cultural identity protected them from developing depression and anxiety (

Siegert et al., 2023).

Another study in ANZ by

Darke and Clark-Howard (

2023) found that a sense of belonging, achieved in many ways, including navigating cultural identities confidently and comfortably, is a protective factor for improving educational outcomes for students from culturally diverse backgrounds. Generally, learners from these backgrounds dominate negative outcome data such as non or low completion rates, low academic attainment and pathways into employment or tertiary education (

Darke & Clark-Howard, 2023). Here, belonging is distinguished from

fitting in. Whereas, roughly defined, fitting in is about assessing a situation and becoming who you need to be accepted, belonging does not require a person to change who they are (

Allen, 2021).

Darke and Clark-Howard (

2023) found that for marginalised and minority youth, a sense of belonging is strongly linked to a sense of security and physical and psychological safety. This is not surprising considering evidence showing that they are more likely than their Anglo-European peers to experience harm, psychological, emotional or even physical harm, such as bullying, racism and discrimination based on how they look, speak/accent, or dress (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

Darke & Clark-Howard, 2023;

Humpage, 2009;

Mar-Rwoth, 2023;

Nakhid, 2017;

Sharma et al., 2025;

R. Simon-Kumar et al., 2022). Creating safe spaces in educational contexts includes taking a critical look at many aspects, such as the curriculum, which, in ANZ, is still arguably based on the Eurocentric model of education and neoliberal models of care for learners (

Darke & Clark-Howard, 2023). Feeling safe and secure to be their authentic self (culturally) is one prerequisite to ethnic youth being able to perform. The opposite of belonging is cultural

code-switching, a form of fitting in and a common practice among ethnic youth. Code-switching is generally defined as consciously deviating from one’s default cultural ways of interaction to meet or match the expectations for behaviour in the dominant culture (

Mannes et al., 2023). For ethnic youth, this is also a way of protecting themselves from further discrimination and cultural fatigue (

Gatwiri & Anderson, 2021;

Mapedzahama & Kwansah-Aidoo, 2010;

Molla, 2023). Psychological challenges associated with code-switching include a lack of authenticity, isolation, frustration, and vulnerability (

Mannes et al., 2023;

Molla, 2023).

1.3. The Benefits of Nurturing and Embracing Multiple Cultural Identities

Evidence shows that embracing their multiple cultural connections is a positive response utilised by ethnic youth to manage the complex challenges they face because of their cultural identity (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023).

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024) reported that African-descent youth in ANZ are often caught between two or many cultural worlds. Finding a balance between them or an alternative space against dominant discourses is a continuous struggle (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). In particular, remaining authentic in these situations. Berry’s theory of acculturation, first developed in the 1970s, helps explain the potential outcomes in such scenarios of cultural tensions (

Berry, 2017). Individuals can

assimilate (solely identify with the dominant culture and sever ties with their cultural heritage). In the case of this study, for instance, embracing Kiwi-ness and cutting ties with their African-ness. They can

marginalise (reject Kiwi-ness and African-ness simultaneously, leaving them without a cultural identity). Youth can

separate (solely identify with their African-ness and reject their Kiwi-ness). The final possibility is to

integrate (maintain aspects of African-ness and Kiwi-ness to some degree or selectively). The latter is often perceived as the most psychosocial healthy stage in racial and cultural identity development theories (

Berry, 2017). Examples of these theories include

Phinney (

1996,

2013),

Sue and Sue (

2003),

Helms (

1990) and

Marcia et al. (

2012). For instance, stage 5 of Sue and Sue’s theory is

integrative awareness, in which the individual has an appreciation of their own cultural identity, a positive attitude towards their cultural or ethnic group and other minority groups, and an appreciation of the dominant culture (albeit this can be done selectively) (

Sue & Sue, 2003). However, there are several stages to reach this point, including the exploration stage, where, for instance, youth are beginning to actively seek more knowledge about their cultural heritage (

Sue & Sue, 2003). A common factor in all these theories is that the struggle to find an authentic cultural identity while navigating multiple cultural identities can create confusion, ambivalence, separation, and a sense of not fully belonging. If not managed healthily, the process can lead to several psychosocial challenges and adverse well-being outcomes (

Phinney, 2013). The theories also prove a strong link between a strong cultural identity and positive psychosocial well-being. For instance, cultural capital, acceptance and pride in one’s cultural heritage can reduce the effects of psychosocial harms such as racial discrimination (

Phinney, 1996;

Sue & Sue, 2003).

The constant negotiation of cultural identities occurs in various domains. These include knowledge of cultural heritage, collective memories, cultural practices, values and beliefs, social connections and relationships, and language (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023). Safe cultural spaces provide forums for building knowledge and even safely contesting some aspects, such as cultural beliefs and expectations (

Fairbairn-Dunlop, 2015).

Mar-Rwoth (

2023), based on personal experiences, provides some examples. For instance, the different perceptions of mental health between generations may often make it difficult for African-descent youth to seek help or support from their families and communities. In some households, mental health is met with secrecy, silence, or the perception that mental illness is a sign of weakness or personal failure, making disclosing mental health struggles a source of stigma (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023).

Nakhid et al. (

2022) reported on how family and community support for queer ethnic youth, which is much needed and relied upon, is sometimes compromised by homophobic attitudes and behaviours influenced by cultural beliefs and practices leading to cultural alienation in a society where ethnic people are already othered. Other areas of intergenerational tensions noted in some studies include gender roles and expectations, and education and career choices (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023). Youth tend to integrate faster than their parents, which may make parents feel left behind or that their children are leaving their ethnic culture behind. Youth may also have opportunities that their parents may not have had and have not experienced. Parents may be unsure how to support their children (

Connor et al., 2017;

Sharma et al., 2025). These are examples of important considerations when creating safe cultural spaces. Given their envisioned importance as a protective factor, it is critical to understand what safe cultural spaces could look like as a care model for youth. Findings from a qualitative study with African-descent youth in ANZ are used to address this gap.

2. Methods

The themes reported in this section emerged from a qualitative study involving African-descent youth living in Aotearoa—New Zealand. This study was guided by participatory action research (PAR) methodology principles. A combination of research workshops (an adaption of focus groups) and qualitative survey questionnaires were used as data collection methods. The Unitec Research Ethics Committee (UREC) approved the research in 2023.

2.1. Research Design

The data used in this chapter are drawn from the same study reported by

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024). PAR’s principles of collaboration, dialogue, storytelling, reflexive critique, and transformation underpinned this study from the design to data analysis stages (

Ayallo, 2012). Regarding

collaboration and dialogue, upon receiving ethics approval, African heritage youth were invited to provide feedback on the research design, specifically data collection techniques and materials, before the active data collection stage. The research team (led by the author) shared the initial research proposal with six self-selected young people in a workshop-style forum. Using simulation techniques, they provided feedback on the appropriateness of the research questions and method. For instance, the researchers initially intended to use workshops as the primary method with all participants. However, after this dialogue, this was changed to qualitative survey questionnaires distributed online and completed anonymously. The age group was modified from the ANZ definition of youth (18–24 years) to the African Charter definition of youth (18–35 years). The youth gave feedback that the latter reflected their daily realities and socialisation even in ANZ (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). The Unitec Research Ethics Committee (UREC) approved the revised age group. The data collection stage was about

storytelling, with participants sharing their lived experiences of navigating multiple cultural identities.

To engage in

reflexive critique, another group of self-selected youth (two were available to participate in the first and ten in the next) were invited to discuss the collected data. The first dialogue was a data analysis process where the youth and research team read through the data and identified and discussed common themes. During this session, the theme of creating safe cultural spaces was identified as a significant and unique contribution that could be explored further. The approved Ethics Application covered their participation, including signing a confidentiality agreement. Accordingly, a second workshop reflecting the principle of

transformation was organised with ten self-selected youth who had also participated in questionnaire surveys to discuss this theme. The focus was on what such a safe space or hub would or should look like. This chapter reports on this and the youth’s perspective on why cultural identity is crucial for them. The entire research process fits an application of a transformative lens. It is an approach that validates the knowledge and experiences of marginalised groups and is committed to initiating change from below (

Ayallo, 2012;

Mertens, 2021;

Mertens & Ginsberg, 2008).

A total of 35 African heritage youth participated in the study, as reported by

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024). All participants completed the anonymous online questionnaires. All participants were invited to the various workshops and could attend depending on their availability and readiness to explore their cultural identity, especially their African-ness, in a group setting. Ten participated in the final workshop, where the study explored what safe cultural spaces could look like. Findings reported in this chapter are drawn from data collected by these two methods.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

Participants, African heritage youth aged 18–35, were recruited using purposive sampling. African heritage means that one or both of their parents or caregivers were born and raised in an African country. They were either born in ANZ or migrated to ANZ at a very young age or up to 18. Participants were recruited from across New Zealand—mainly Auckland and Wellington, where these population groups are mostly based. The researchers utilised their professional relationships and networks to recruit potential participants. These included professional groups and community-based organisations that provide social, legal, and educational services for ethnic communities in ANZ. Information about the research was circulated through these networks. Potential participants who matched the inclusion criteria self-referred by contacting the lead researcher. The final group of participants were provided with comprehensive information about the research, consented, and voluntarily participated. A total of 35 youth participated in the study.

2.3. Final Research Workshop Recruitment

After the data analysis workshop, where the theme of creating safe cultural spaces was identified as significant, an invitation was sent to all participants requesting their participation and input on what such a space would consist of. Ten young people were invited to a 1-day long workshop. The research funding included a koha (gift) for their time and contribution and kai (food) during the day.

2.4. Data Collection

The researchers facilitated the distribution and collation of the survey questionnaires (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). However, only Irene Ayallo facilitated the final workshop.

Survey questionnaires: The anonymous questionnaire was created using Google Forms, and the link was distributed directly to all the participants through their provided email addresses. The questionnaires generally contained questions about their perspectives on cultural identity, such as what it meant to them and the cultural identities they identified with. They were also questioned about their experiences negotiating these identities while participating in daily life and domains in NZ, the opportunities and challenges encountered, and views on specific support needed to thrive.

Workshop: Participants who registered interest in participating in the final workshop were sent an information sheet, which included the location of the workshop, the agenda for the day, and an overview of the questions for discussion. On the day, the researcher used a combination of trigger and problem-solving questions and small group activities to facilitate discussions. For instance, after introducing a question, participants were divided into small groups (2–3 in a group) to discuss it and then returned to share their perspectives with the whole group. This technique was used to ensure participation from all participants. The lead researcher took notes, and, in some instances, the small groups were provided with flipcharts to write down key ideas. Generally, participants were queried on the benefits of safe cultural spaces, the kind of things they would like to happen in these spaces, the difference such spaces would make, and who the participants would be.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis process was informed by PAR’s transformative lens (

Mertens, 2021), narrative inquiry (

Clandinin & Caine, 2013), and inductive thematic analysis (

Clarke et al., 2015). The process involved a thorough reading of questionnaire responses and research workshop notes, coding, and generating themes from these codes. Questionnaire responses were reviewed individually (by the researchers) and collectively (during workshop 2). The author analysed data from the final workshop. Responses to each question were reviewed many times, common words, terms and phrases were identified and used as codes, and themes were generated from these codes. Following narrative inquiry methodology principles, the meanings and implications of these themes were then situated in existing research (

Clandinin, 2006). The author ensured rigour and trustworthiness using reflexive practice, including regular debriefing and consulting with practitioners and researchers with relevant expertise (

Creswell & Poth, 2016).

The previous publication reported three main themes using the same data set (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). It was evident in these themes that Africa-ness and Kiwi-ness were, in equal measures, important to the youth. They desired to embrace both and even more strongly to reclaim their African-ness. The creation of safe cultural spaces was suggested in this context. Accordingly, the following section reports on two main themes. The importance of cultural identities and the role of culturally safe spaces in supporting youth to embrace their African-ness and Kiwi-ness.

3. Results

Participants’ characteristics were described in the first publication using the same data set (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). A summary is provided in

Table 1 below.

3.1. Characteristics of Participants at the Final Workshop (n = 10)

As described in the methods section, participants in this final workshop were self-selected. Of the 10 participants, one was 18, four were aged between 20 and 29, and five were over 30 (30–35). Four participants identified as female, and the rest (six) identified as male. Two youths were born in ANZ, and the rest of the participants were born in an African country and migrated to ANZ. Regarding African countries of heritage, all the subregions were represented. African subregions are used in this reporting to anonymize participants’ countries, especially where the data was small and participants can be easily identified. Participants at the workshop represented all three immigration pathways identified in the table above.

The characteristics of participants in this study are provided mainly to show the broad spectrum of the reported themes.

3.2. Theme 1: Perspectives on the Importance and Role of Cultural Identity

This theme was generated from a question asking participants’ reflections on the extent to which cultural identity was vital to them, irrespective of whether, based on their experiences, they have successfully or unsuccessfully navigated their cultural identity (or identities). Prompts were provided in the questionnaire to help with the reflection. These included: is cultural identity important? Why is it important? If not important, why is this so?

All participants in the study stated that cultural identity was important to them. There were no notable differences in responses across age groups, gender, country of origin, or years spent in ANZ (i.e., born here or migrated young). The reasons provided were generally associated with cultural identity being a source of values, beliefs, morals, self-esteem, personhood, and a sense of identity and belonging. For instance, P10 observed that,

I strongly believe that cultural identity is important because it shapes who we are. In simple terms, discovering one’s culture is discovering one’s identity. It helps us to understand the world from a different perspective and it also helps to approach some situations of life with a different perspective. So, it is VITAL [sic].

Cultural identity as personhood (

Hall, 2014) was echoed in P30’s statement, “

I believe it’s really important because it’s part of who you are. How you think…how you interact and see the world is based on the culture and traditions that made you who you are…”

According to the participants, having a cultural identity was

their something different. As stated by one participant, “

Cultural identity is very important, especially when we are not in our homeland, because we have to have an identity that people can distinguish us from others. If not, we are lost… (P15)”. This perspective aligns with the observation that migrant communities can utilise cultural identity to maintain uniqueness, something that contrasts them from the dominant identity (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024;

R. Simon-Kumar, 2019). It also provides a sense of identity in a context where they

look different, as P35 describes. “

Cultural identity is important because it is who you are… No matter how hard one may try or may successfully fit in a certain environment, the first thing that people will see is the colour of their skin. And we can’t control how people or certain groups of people will perceive us…”.

One participant explained the importance of cultural identity by stating how knowing and embracing their cultural identity has positively impacted them.

…for me, knowing and being proud of my Eritrean background has provided me with so many different experiences, beliefs, and perspectives. I have felt a greater sense of belonging…my self-esteem has improved…and I have been able to navigate the world with a much deeper understanding because I have strong morals, beliefs and expectations that allow me to feel safer. This is why I want to continue to explore what it means to be Eritrean and Kiwi…

P20

Another participant also highlighted the need to continue exploring. P4 stated,

Knowing where I come from has given me a sense of belonging and my cultural identity, which has been very important. In saying that, I feel like, because of the many spaces I engage in, it is becoming something I have to construct every day, and maybe my whole life… or my culture, start to lose meaning…if that makes sense…like how do I continue being African and Kiwi…

Participant 4’s experience demonstrates the stages of cultural identity formation described in theories such as by

Phinney (

1996) and

Sue and Sue (

2003), specifically

exploration and

integrative awareness. However, the narrative provides a glimpse into possible cultural fatigue and confusion (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024), which, if not managed healthily, may lead to responses such as

code-switching (

Mannes et al., 2023),

assimilation,

marginalisation, and

separation (

Berry, 2017). These responses show that youth need targeted support to explore cultural identities in safe spaces.

3.3. Theme 2: Perspectives on Support Needed to Navigate Multiple Cultural Identities Successfully

Youth participants were also queried about the specific ways of supporting African-heritage youth to explore their multiple cultural identities safely and successfully. The prompts for this question included: What works and what does not? What needs to be done to address these in ethnic communities?

First, in their responses, most participants stated that ways of support that worked encouraged them to be themselves and proud of who they are and where they come from. For instance, P7 summarised this as follows, “something that gives me room to be myself…in an environment with people who understand where I come from. Otherwise, I have to dim and dial myself down to fit it”.

Secondly, descriptions of what works included the following common phrases or terms: forums and platforms free from judgement and discrimination; forums with people from similar cultural backgrounds and identities; platforms for teaching and reminding each other where we come from; places for passing on our culture to the next generations; forums to keep up-to-date with what is happening in our countries of origin; places to enable us to adjust to a new life and new country; and opportunities to participate in cultural programmes actively. The following responses provide a good summary of the participants’ views. P15 stated,

I think there should be more platforms and forums for young people with similar cultural backgrounds and identities to be in and interact with each other, like events and such, as it would bring us closer to our original cultural identities. It would also be a way for young people to organically form relationships with others who are like them and have shared experiences.

This view was supported by P2, stating that facing the challenges individually can be lonely and isolating. “I think it’s just giving people with these experiences opportunities to mix with people who’ve been through the same experiences as us. It can feel lonely and alienating to navigate it on your own. Allowing forums for us to speak on these things”.

There was a recognition that some young people were still exploring their heritages and, therefore, needed spaces and people to support them through this, as noted by P22.

I believe passing on the legacy of our cultures to our generation is crucial…I try to teach my fellow African youth our traditions. It works mostly when we have community gatherings, African occasions/celebrations/parties, etc.… but it is also important to have a space to learn about who we are in this new country…what makes us unique…

P26, echoing P22, stated, “Tradition is great, and hearing how our parents lived is amazing, but there could be space for who we are today, too”.

The kind of support that worked included practitioners who understood young people’s cultural backgrounds and the conflicts that may often arise between their new ways of being and their parents’ ways and still support them in a culturally safe manner. P15 provided a lengthy example,

We place great value and respect on our parents, and most of the time, we aren’t able to voice our opinions or concerns regarding doing things differently… I remember I had an issue in my household… I felt I couldn’t get any Uni work done, and my mental health was in the rubbish bin [sic] because I still had all my housework to do, which is pretty much everything… Anyway, I contacted someone for some help, and the first thing they suggested was that I move out of my house. Don’t get me wrong, that was my first thought as well for a long time, but girls don’t just move out in my culture until they are married or living in a mother country/city. It felt like that suggestion was inconsiderate (even though it wasn’t!!) because they didn’t consider my culture… I guess what I’m trying to say is if you want to support youth like me…take into consideration their cultural responsibilities and cultural traditions.

Participants mentioned platforms, forums, and safe spaces many times. This prompted the follow-up workshop, where we explored what these spaces could look like and the things young people wanted to see in these spaces.

3.4. Theme 3: The Creation of Safe Cultural Spaces

Two main questions were used to facilitate discussion during the 1-day workshop. These included what youth would like to happen in these spaces and who the participants would be. As Group A summarised, all participants agreed that the spaces should be “for youth of African heritage…with similar cultural background and dealing with similar challenges…” Asked why this was important, all groups stated it was “safe, no judgement, and no discrimination” for them. All participants agreed that these spaces could be physical or online spaces.

The sessions that followed explored what youth wanted to see in these spaces. As reported earlier, this was performed in small groups (2–3 in each group), then shared in a main session (with all participants). The lead researcher facilitated the feedback session, taking notes, i.e., on flipcharts.

Figure 1 below shows examples of notes taken during the workshop.

In the analysis process, the researcher summarised these into four main areas/spaces:

Space 1: Space for collaboration and connections

Participants described the need for an informal space to connect and share experiences in a relaxed environment. Examples of activities or things provided for this space included:

Space 2: Spaces for support and mentorship

Participants described the need for an educational and mentorship space. This was generally described as a space organised around their educational needs. For example, one participant gave an example of how they struggled to decide what they wanted to do after high school. They did not know whether or not they wanted to attend university and, if they did, what program they wanted to do. The participant mentioned that this could have been a helpful space to support her. The participant stated, “I ended up choosing a program only because that is what my parents wanted… but I had no interest in it. That was a waste of money…and I wished someone guided me…”.

There was a general feeling among participants who had similar experiences in high schools and universities that targeted support is still lacking for ethnic students, especially African-heritage learners. They also felt that their parents, even though willing, did not know how to support them through these decisions. As participants from B described, “…most of us have been through that… our parents lived through a different time. We know they want to support us. But I think they just don’t often understand some of the struggles we go through, say at uni…”.

Connor et al. (

2017), in their research with African mothers in ANZ, reported that parents struggled with this too.

Youth also desired a place of mentorship where youth at different stages, such as high school, university, or employment, could come and talk to their peers about their experiences and support them. A participant from group D stated,

…like after high school, I know the expectation for most of us African kids is to go to uni…but I didn’t want to go to uni. I wanted to get an apprenticeship and get into a trade… I didn’t know anyone from my community or friends who had done that…so it was a difficult decision to make. I ended up going to uni, didn’t like it… dropped out…

Space 3: Spaces for learning about culture

All groups described this as a space that brought African culture to them. Most mentioned that this space helped maintain and learn about African culture. Examples of things to do in this space include:

Read African books and literature

Access research by African-heritage students in ANZ

Form cultural groups

Learn and practice African languages

One group offered the following description. “…Sometimes at uni, we really want to bring African flavour or explore African topics…and we find it challenging because we don’t know where to get the resources required to support our views…”

Space 4: Spaces for well-being and personal growth

Finally, participants desired a place to access support to support their well-being in various areas. Notably, the emphasis for most was that they wanted to engage with culturally safe professionals in this space. These people were described as those who understood their cultures and could advise appropriately. Some of the topics they wanted to explore in this space include the following:

Learn and know their rights and responsibilities as citizens. Commonly mentioned areas of concern included employment, tenancy, immigration, and family disputes.

Mental health support was mentioned and emphasised by all groups. The comments from all groups implied that this was an area where African-heritage youth lacked and needed support. One group described,

We rarely talk about mental health in African households…you know…it can be seen as a weakness. But we go through a lot…some of us have tried counselling, and most of the time, counsellors who do not understand our cultures are not very helpful… For example, telling us to leave home and get our own place when we are having issues at home…with our parents…is not helpful… We are African kids at the end of the day…we don’t just pack out things and leave home…it is like leaving your village and support system behind…

The experience described by the group above is similar to the observation made by

Mar-Rwoth (

2023) when describing her experience of

living in two worlds.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study on African heritage youth’s perceptions of the importance of cultural identity and creating culturally safe spaces to strengthen their multiple cultural identities supports the research connecting strong cultural identities and healthy psychosocial well-being among ethnic youth (

Chubb et al., 2024;

Mar-Rwoth, 2023;

Sharma et al., 2025). Findings from this study build on (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024), which demonstrated the personal, communal, and societal complexities faced by these youth in ANZ while constructing and navigating their many cultural identities, particularly their African-ness and Kiwi-ness. The current study shows that the already challenging process is exacerbated by their ethnic minority status, which has been established as a marker of social disadvantage. Additionally, youth undergo this process alongside the normative developmental tasks of adolescence and young adulthood (

Sharma et al., 2025;

N. Simon-Kumar, 2023). Most participants expressed that in the context of immigration, cultural identity provides them with a sense of

uniqueness, more so for participants who already felt

othered based on

visible differences or attributes. Cultural identity almost gives them validation of why they are or should be

different (

Ayallo & Rasheed, 2024). For instance, their African-ness is a heritage that cannot be erased or denied. Their Kiwi-ness is who they are now. Accordingly, the youth desired to reach the stage of integration (

Berry, 2017), integrative awareness (

Sue & Sue, 2003), ethnic identity achievement (

Phinney, 1996,

2013), or autonomy (

Helms, 1990). Generally, this is the stage where youth proudly, comfortably, and authentically live out their African-ness and Kiwi-ness while navigating experiences and challenges constantly posed by social exclusion owing to their ethnic minority status. The findings support the literature showing that the struggles can also be internal, originating from within their communities (

Nakhid et al., 2022;

Sharma et al., 2025). An example cited by most participants was perceptions of mental health, whereby some of the caregivers/parents, because of their socialisation, may view such struggles as a weakness and something to be approached with secrecy. This made it difficult for them to seek help from their community and non-ethnic practitioners who did not understand their cultural worldviews. Therefore, unsupported and in a culturally responsive manner, ethnic youth can experience confusion, separation from their African-ness and Kiwi-ness, and ambivalence about where they belong. Research shows that these can lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms and adverse psychosocial challenges (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023).

The study highlights that youth are at different stages in living their authentic cultural selves, attempting to integrate and balance their Kiwi-ness and African-ness. Regarding the typical stages referred to by racial and cultural identity development theories, for instance, (

Sue & Sue, 2003), the participants were between the last three stages: resistance and immersion, introspection, and integrative awareness. While (regarding the resistance and immersion stage) none of the participants expressed explicit views that completely rejected the dominant culture represented by Kiwi-ness, participants indicated a lack of trust, particularly for people in the dominant culture who held racist ideas. This is the primary reason participants gave why the created safe cultural spaces should only be for ethnic youth, to protect them from hatred and discrimination. Their views align with research showing that for ethnic minorities, a sense of belonging is intricately tied to psychological and physical safety (

Darke & Clark-Howard, 2023). The majority were in the introspection stage, grappling with embracing aspects of the dominant culture without losing or being disloyal to their African heritage (

Sue & Sue, 2003). Given their unique multiple identities, there was also a realisation that both sides consisted of what works and does not work for them as ethnic youth (

Mar-Rwoth, 2023;

Sharma et al., 2025). Most participants were still working out what authentically living in both cultures meant to them (integrative awareness) and how to sit with the realities of belonging to othered ethnic minority groups. As a model of care, they envisioned safe cultural spaces as the forums and platforms that would enable them to achieve this stage of cultural identity development.

While the notion of creating safe cultural spaces is not new in the context of supporting minority and marginalised groups (

Bustamante Duarte et al., 2021;

Chubb et al., 2024;

Tualaulelei & Taylor-Leech, 2021), the perspective provided in this study is unique to African heritage youth in ANZ. The proposed nature and activities in these spaces are based on their lived experiences. These are spaces free from judgment, discrimination, and harm. They are spaces where their African-ness and Kiwi-ness meet, and youth can construct, deconstruct, and reconstruct what these identities mean to them in their day-to-day lives. Hence, they proposed forums for informal conversations within these spaces to share experiences, interests, and questions in a relaxed environment. Formal spaces were proposed to support them in navigating the more critical domains, such as education and employment. An activity mentioned in this space was mentorship in areas such as further education and career choices, offered from a cultural safety perspective. This suggestion supports the emphasis that these forums are not meant to be simply

warm and fuzzy (

Fairbairn-Dunlop, 2015). They should challenge youth and connect them to greater knowledge bases and skills. These are spaces for capability building and growth. The benefits envisioned for Pacifica youth could be projected for African-heritage youth in ANZ, given their similar experiences in many areas (

Chubb et al., 2024). For instance, participants in the current study spoke about ways culturally safe spaces can enhance positive educational outcomes. For example, activities in these spaces may mitigate challenges such as non-engagement, disengagement, and poor decision-making in education and career choices.

Some limitations concerning the reported findings need to be considered. First, only a small sample of African heritage youth living in ANZ participated in this study. For instance, it cannot present information explaining all factors that could be considered in creating safe cultural spaces. Therefore, the findings can only be cautiously generalised to all African heritage youth in Aotearoa. The paper remains cognizant of the different immigration pathways and their associated experiences. For instance, while there are many commonalities, the experiences of youth who migrate voluntarily and those who forcibly migrate differ. The effect of the immigration pathway on cultural identity, and therefore how the different pathways may affect how youth perceive safe cultural spaces as a model of care, was not a variable utilised in this study. Further research with specific groups may be needed to highlight differences between youth who voluntarily migrate and those forced to relocate.

Despite these limitations, the present study presents new information on a model of care that is culturally responsive and based on experiences specific to African heritage youth living in Aotearoa. The significance of this study is that it gives voice to and validates the experiences of the youth in this study. It reports the diverse narratives of African heritage youth from their perspectives. This model of care could be helpful for practitioners working with these youth to support them holistically. As also argued by

Ayallo and Rasheed (

2024), the methodological approach ensured that the voices of young people were included in critical stages of the research, which attests to its transformative commitment and change from below.

This paper has achieved its aim of exploring a model of care for African heritage youth that would support them in their journey of navigating and authentically living their

African-ness and

Kiwi-ness. It has highlighted areas to consider in creating these safe cultural spaces for these youth. The African-heritage youth in this study provided a picture of what a culturally safe space would look like or consist of. The key elements are summarised in

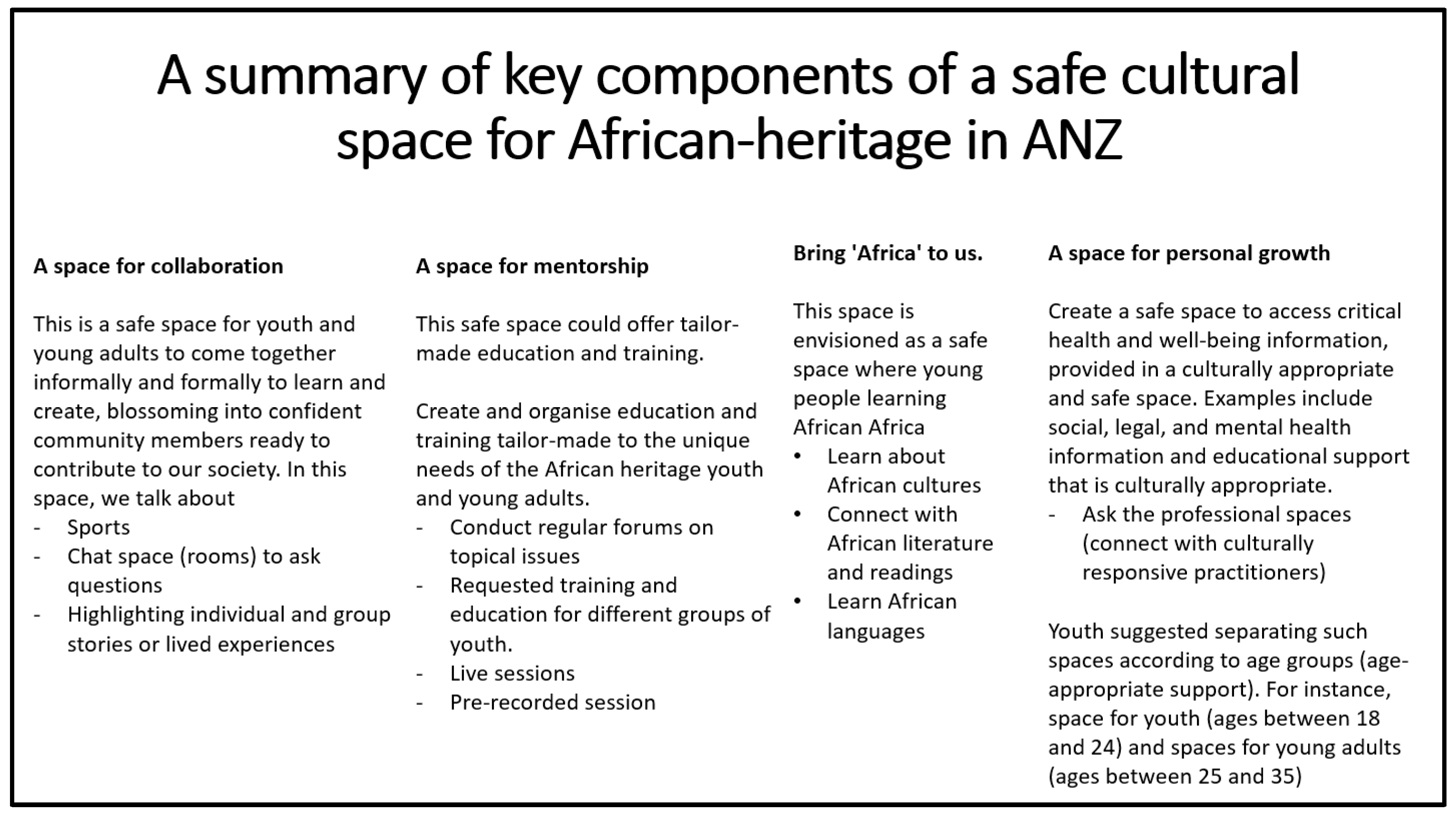

Figure 2 below.

As mentioned in the introduction, some community-based organisations across ANZ offer support services specific to African-heritage youth. However, evidence shows these are not coordinated, and each organisation tends to focus on only one or two of the areas suggested by the youth in this study. Instead, the spaces the youth recommend in this study are coordinated and holistic. The practicality and conceptualisation should be investigated further. Accordingly, the paper suggests further research, such as a participatory-action-based pilot hub, with a large sample of youth to design such a holistic and coordinated safe cultural space.