1. Introduction

Community-based arts programs for youth are vibrant in the U.S., providing young people with opportunities for artistic skill-building as well as potential benefits in well-being, identity development, and social–emotional learning (

Bowen & Kisida, 2023;

Halverson & Sheridan, 2014;

Ngo et al., 2017). Many youth arts programs make culture a central focus by catering to the needs and interests of youth of color. Such programs, which we call Culture-centered Community-based Youth Arts (CCYA), offer exposure, opportunities, and pathways for young people, particularly youth of color. Examples include an instrumental music program that prioritizes Black composers, a visual arts program that centers graffiti art and hip-hop history, and a program that provides exposure and training in Mexican folkloric dance. As the arts represent an important component of culture, CCYA programs intertwine identities, learning, and expression in cohesive and powerful ways. Such programs have not been delineated in current scholarly literature. In this essay, we introduce and describe CCYA programs, drawing on scholarship from multiple fields, including youth development and urban education, focusing on the potential for CCYA to positively impact well-being.

Community-based arts opportunities are unique as a case of art involvement that youth and families often seek out beyond school-based opportunities. Arts education opportunities outside of school, in connection with community-based organizations, can be grounded in cultural experiences relevant to their communities (

Akiva et al., 2024;

Bushnell, 1970). These culturally linked spaces may provide added psychosocial benefits for participants, as arts-interested youth engage based on their interests and on their own time. How might these unique arts learning spaces, rooted in culture and community, use the arts as a tool for well-being, healing, and maybe liberation (

Buyukozer Dawkins et al., 2021)—and do this with a youth development lens? It would also be important to take an approach that acknowledges the importance of context for people of color in different cities, as unique sociohistorical realities in different regions may inform the development of such programs.

This paper conceptualizes Culture-centered Community-based Youth Arts (CCYA) programs that intentionally serve communities of color by incorporating culture into art practice. Connected to the broader field of creative youth development (CYD), CCYA programs are often operated by and, definitionally, for communities of color. Access to the arts for youth of color has steadily declined over the previous four decades. This decline has been primarily due to the drastic reduction in school-based arts programs, which began in the 1980s and is particularly pronounced for Black youth (

Rabkin & Hedberg, 2011). Youth in the U.S., particularly youth of color in public schools, have suffered from education policy prioritizing an academic achievement discourse at the expense of whole-child development approaches in education (

Howison et al., 2022;

Armstrong, 2006). As noted by

Akiva et al. (

2024, p. 5), this “trend of declining arts access for Black youth is antithetical to the significance of the arts as an aspect of community cultural wealth for Black people in the US” Cultural context is centered on the arts, as art reflects culture. Our CCYA conceptualization builds on inquiry about the experience of arts-involved youth from diverse cultures in the US to understand how communities use arts to support youth development. Community-based youth arts programs that emphasize artistic excellence and use a culture-centered approach represent potentially uniquely powerful developmental experiences for youth of color and avenues to increased well-being.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

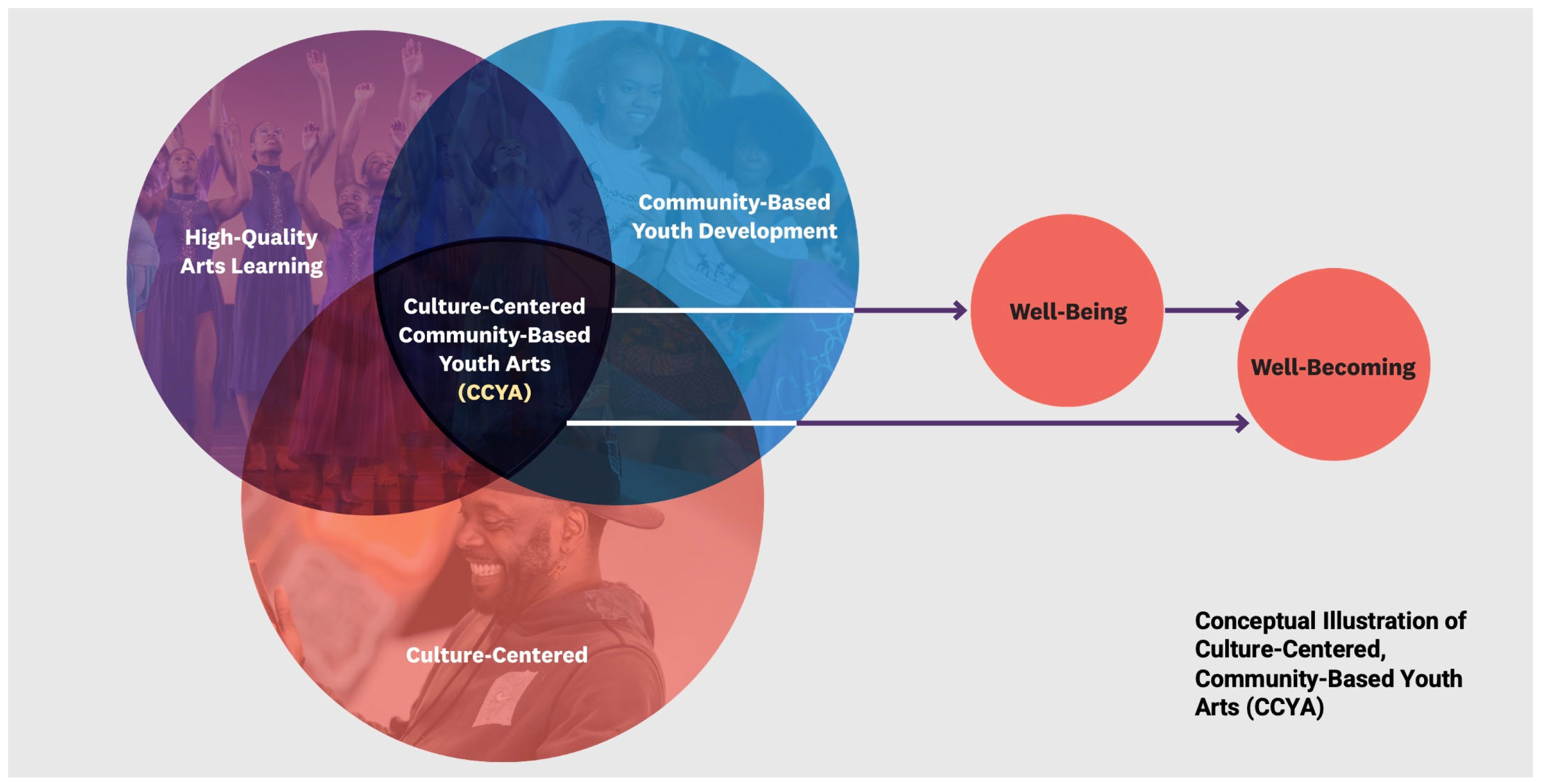

This conceptualization of culture-centered, community-based youth arts (see

Figure 1) is anchored in studies demonstrating how the arts might support well-being. Though considerable scholarship on the benefits of arts has focused on academic-related outcomes adjustment (

Fredricks & Eccles, 2008;

Mahoney et al., 2003), others push for broader approaches that de-emphasize the idea that the arts are beneficial only if they transfer to academic skill building (

Winner et al., 2013). For example, involvement in the arts has been shown to strengthen critical thinking, compassion, and citizenship (

Bowen & Kisida, 2023;

Winner & Hetland, 2008). One review noted a relationship between involvement in creative learning and self-confidence, self-esteem, social skills, and positive behavioral change (

Bungay & Vella-Burrows, 2013). These were seen as non-cognitive benefits of involvement in the arts for youth. Such outcomes are aligned with our understanding of well-being and healing, which support holistic development for young people.

Research on well-being spans various fields, with positive psychology offering a particularly insightful perspective.

Seligman’s (

2011) PERMA model outlines well-being through five key elements: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement. Although not exhaustive (

Seligman, 2018), these components are widely applicable and form an empirically validated and coherent theory of well-being pertinent to youth involved in the arts. Studies have shown connections between arts education and each PERMA element (

Villegas & Raffaelli, 2018;

Froh et al., 2010;

Dworkin et al., 2003;

Malin, 2015;

Catterall, 2009). Well-being also looks like liberation. Although many psychological theories of well-being are neutral about race and do not directly address equity concerns, research has identified links between racial identity and psychosocial well-being. For instance,

Johnson and Carter (

2020) highlight a correlation between Black Cultural Strength and psychosocial health, a measure of well-being.

The early studies on the benefits of the arts focused on art participation in school, which led to gaps in understanding unique benefits for youth of color since they have less access to the arts in their schools (

Rabkin & Hedberg, 2011). The systematic and systemic decline influences the lack of understanding on this topic in arts involvement for marginalized communities. The decline in school-based arts involvement has led to a proliferation of community-based arts programs that invite teaching artists and community members to train youth in the arts (

Akiva et al., 2024). One relevant framework for community-based youth arts is the connected arts learning framework, which emphasizes creating meaningful learning experiences by connecting arts to young people’s interests, identities, and real-world experiences (

Peppler et al., 2023). The connected arts learning ecosystems may involve schools but are rooted in neighborhoods and communities that primarily engage youth in out-of-school time.

The mechanisms through which culturally connected arts experiences provide benefits for youth of color is an understudied phenomenon. Culturally connected arts experiences are rooted in communities of color, specifically to serve the youth and families in those community. Using a community cultural wealth and culturally sustaining theoretical frameworks (

Paris, 2012;

Yosso, 2005) allows us to better understand this niche area of youth arts programs. A closer look at these programs necessitates an examination of structural limitations to experiences that promote well-being for communities of color and acknowledges the need for culturally responsive and sustaining frameworks that support arts programming.

3. Methodology

The conceptualization of CCYA programs is informed by our experiences both as researchers and community members, living and working in urban enclaves in the U.S. Collectively, we have five decades of experience observing youth arts programs across multiple cities. Across multiple research projects, we have managed over sixty program observational experiences of youth arts programs. More specifically, we engaged in cross-age focus groups that felt more like interactive program experiences than research. Designed in alignment with a transformative evaluation approach (

Ord et al., 2018), these engaging workshops, as they were called, allowed youth and teaching artists to describe memorable youth arts program experiences. Conversations with specific types of programs have helped us devise our understanding of the unique phenomena represented by programs that serve youth of color in high-quality arts experiences that occur in out-of-school time.

The following sections elaborate on the three components of CCYA programs: an emphasis on high-quality arts, being anchored in community-based youth development, and using culture-centered approaches to support involvement in the arts for youth of color. We will articulate how these programs, by design, support well-being for participating youth. In describing these three components of CCYA programs, we connect to relevant theoretical frames useful for enhancing understanding of the ways these programs benefit young people, families, and communities. Additionally, each section begins with a vignette describing our experiences of a program we observed in our research. These brief descriptions should ground the conceptualization in program practice and help create context for the dynamic creative learning experiences that support development in communities of color.

4. High-Quality Arts

Sound Rising1 provides rigorous instruction in instrumental and choral music and performance pathways to youth residing in communities with limited access to arts resources. The program is classically music focused and intentionally features composers of color. Sound Rising emphasizes intensive, specialized training, focusing on performance-based skills and artistic development. Young people attend several times per week for individual lessons and ensemble rehearsals. Culture-centered, community-based arts programs invite youth to develop skill in an area of the arts, based on personal interests. An example might be a conservatory-style instrumental music program that prioritizes artistic excellence and lifts up Black composers and musicians. Youth typically self-select into CCYA programs based on a love for or curiosity with singing, theater, visual arts, instrumental music, dance, etc. These programs go beyond exposure to the arts, aiming to train young artists to value artistic excellence. Arts learning in these spaces requires intense commitment and engagement, which can lead to flow states (

Dawes & Larson, 2011). Indeed, in a classic experience sampling survey, where youth noted their psychological states during various activities, youth had high intrinsic motivation and high concentration during arts, hobbies, and sports as opposed to other common activities such as being in school or hanging out with friends (low motivation/high concentration in schools; high motivation/low concentration hanging out with friends;

Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1984;

Larson, 2000). This type of engagement is definitional to our understanding of well-being (

Seligman, 2011). The art produced in such programs is expected to surpass ordinary “novice” art and expose young people to master classes, accomplished teaching artists, and even advanced training opportunities that can enhance skill. Participants in CCYA programs are engaged in these programs because of aesthetic value, imaginative possibilities, and joy. Not because of the purported academic or other instrumental gains associated with the arts. This aligns with

Greene’s (

1977) discussion of the “imaginative mode of awareness” (p. 15) that happens when young people engage in the arts. The arts make one more alive, as they experience “expression in a particular medium: paint, language, the body-in-motion, musical sound, clay, film…textures, color, area, space.”

4.1. Arts as Central

CCYA programs do not exist to use the arts to help youth learn about important topics, such as environmental justice, human rights, or STEM. In other words, CCYA programs do not make instrumental goals primary for arts, though they may achieve non-arts goals in a secondary way. Programs that use the arts have value as youth development spaces that often use creativity as a tool to invite engagement (

Goessling et al., 2021). But those programs, where arts is a means, would not qualify as CCYA. Rather, in CCYA programs, art is the central focus, purpose, and motivating basis of the program, and youth train in the technical skills required to become advanced in their craft. This may happen in individual endeavors like visual arts production, or in group pursuits like mounting a musical theater performance. CCYA programs also promote a true, enduring arts appreciation that can shape youth’s experiences into adulthood. As art appreciation is subjective and people can differ in their views of what is excellent, we use arts appreciation to reflect a goal of performing art well, developing skill, and creativity.

4.2. Skill Development

High-quality arts learning programs provide opportunities for artistic development in three distinct ways. First, they invite youth into creative expressions, which leads to flow experiences and opportunities to detox from life challenges and heal through the arts. Second, they support youth in acquiring artistic skill, engaging in artistic critique, and embracing continual practice in a way that invites growth and builds confidence. Finally, high-quality arts programs provide stages for performance and displays of artistry that engage the community as an audience and provide youth an opportunity to shine, ultimately enhancing appreciation for the arts for youth and their audiences.

4.3. Connections Between Well-Being and High-Quality Arts

Considerable scholarship examines the potential for arts education to affect academic achievement (

Catterall et al., 2012;

Hetland & Winner, 2004), which is relevant as achievement can be considered an element of well-being. However, in contrast,

Eisner (

1998) viewed the arts as a cultural experience with intrinsic value, independent of academic outcomes. He advised against promoting arts education for instrumental benefits like academic success and focused instead on its role in enhancing well-being. Similarly, in the context of arguing against educational standardization,

Greene (

2013) argued that the arts are essential for learning, and should not and cannot be standardized. She noted that standardization efforts often marginalize and exclude the arts from schools (p. 251).

Greene (

1995) also emphasized that engaging with the arts is the best way to “release the imaginative capacity” of young people (p. 379).

Eisner (

1998) suggested that arts education allows youth to transform their ideas into art and become more attuned to the aesthetic qualities in both art and life. He argued that more appropriate outcomes include a greater willingness to imagine possibilities, a desire to explore ambiguity, and an ability to recognize and accept multiple perspectives. Unfortunately, youth of color are often subjected to schooling experiences that are rigid, standards-focused, and even dehumanizing (

Love, 2019). Learning should include humanizing opportunities that engage youth through positive developmental capacities that affirm and uplift. Both Eisner and Greene stressed that high-quality arts education is a crucial developmental activity that broadens one’s sense of self and cultural identity, which is particularly valuable for understanding students of color in out-of-school time arts programs.

5. Community-Based Youth Development

Beyond the Page is a youth literary arts program centered on the power of the written and spoken word. Through creative writing, youth publishing, and performance poetry, the program fosters artistic expression and storytelling. At its heart, Beyond the Page is a youth development program, prioritizing relationship-building and personal growth through creative exploration. Deeply rooted in the community, the program offers public performances, writing workshops, and collaborations with other youth-serving organizations.

Community-based youth programs serve young people through engaging programs that offer interest-based learning and development experiences. As positive developmental settings, they represent many benefits to participating youth, including physical and psychological safety, supportive relationships, opportunities to belong, and integration of family, school, and community efforts. They are typically community-embedded, offering community concerts, festivals, workshops, and establishing partnerships with other programs and community-based organizations. Though community-based youth programs serve young people in out-of-school time (OST) settings, they often closely affiliate with schools and even offer enrichment programs as part of the school day. This provides an entry point for programs to identify and engage youth who are often in schools with limited budgets for enrichment opportunities.

However, access to arts education in the United States is uneven, with a notable decline in arts programs in public schools for youth of color starting in the 1980s and continuing through the early 2000s, according to retrospective panel studies of adults (

Rabkin & Hedberg, 2011). While assessing availability at the school level can be challenging, recent analyses of 2009 school data revealed that arts availability is influenced by school size, type (e.g., public vs. private), and the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced lunch (FRL;

Elpus, 2022). The 2019 National Arts Education Report, which included over 30,000 schools serving 18 million students, found that arts and music access was lowest in schools with majority Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous students and in schools with high FRL percentages (

Morrison et al., 2022). The reduction in school-based arts opportunities, particularly for marginalized youth, coincided with the rise in community-based youth arts organizations and teaching artists (

Akiva et al., 2024;

Rabkin & Hedberg, 2011). Consequently, many young people now receive arts education through community-based youth programs (

Montgomery, 2017).

5.1. Rooted in Community

Eccles and Gootman (

2002) provided a framework for the role of community-based youth development programs that serve young people in out-of-school contexts. Nonprofit organizations usually operate community-based youth programs and may or may not be connected to larger, national groups (e.g., Boys and Girls Clubs of America). These programs provide learning experiences after school, during the weekend, and/or summer opportunities. Learning is cultural. Schools are cultural institutions that promote and emphasize dominant cultural mores that may or may not reflect the population served (

Nasir et al., 2013). Accordingly, people groups often formed community spaces to reflect the values and mores rooted in the community (

Bushnell, 1970;

Baldridge, 2017). Youth arts programs represent, reflect, and are shaped by the neighborhoods served. At the same time, they contribute to the fabric and texture of the communities by offering art for the community to consume. This bi-directional relationship—the community defining and program and the program defining the community—represents the inherent strength of CCYA programs.

5.2. Focus on Youth Development

Youth development encompasses the extensive scholarship and practical foundation linked to the positive youth development movement. The federal government defines positive youth development as an intentional, prosocial approach that recognizes, utilizes, and enhances young people’s strengths (

www.youth.gov, accessed on 12 September 2024).

2 The approach prioritizes providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships, and offering the necessary support to build on young people’s voice and leadership abilities. Youth development programs are characterized by their strengths-based, relationship-focused, and holistic nature. Recent perspectives on positive youth development emphasize the importance of a social justice lens in understanding and conceptualizing these programs (

Baldridge et al., 2024;

Gonzalez et al., 2020;

Lerner et al., 2021). Community-based youth development programs integrate positive youth development frameworks within the context of youth programs, which are typically operated by nonprofits rooted and often embedded within the communities they serve. The concept acknowledges interdependence between positive and healthy youth outcomes and healthy communities. Programs aligned with community-based youth development can play an important role in helping youth be prepared to become well-rounded, engaged citizens as adults. Community-based youth programs that fit into our CCYA framework are valuable developmental spaces in that they do two key things. First, they foster intergenerational relationships within communities, linking youth to local teaching artists, previous program participants, and peers who have mutual interests in the arts. Secondly, CCYA programs partner strategically with organizations in the local ecosystem to support sustainability and resource sharing, which allows programs to meet the more comprehensive needs for youth and their families.

5.3. Connections Between Well-Being and Community-Based Youth Development

The Connected Arts Learning framework (

Peppler et al., 2023) suggests that arts learning should be interest-driven, focused on relationships, and connect youth to future opportunities. Each of those ideal outcomes of arts learning is connected to our psychosocial well-being framework. Interest-driven activities foster engagement and can lead to flow (

Dawes & Larson, 2011). Relationships are at the heart of psychosocial well-being (

Camara et al., 2017;

Mertika et al., 2020), and arts programs can offer built in relationships for young people to experience belonging (

Ballard et al., 2023). When programs connect youth to future opportunities, they facilitate pathways to achievement and a sense of accomplishment (

Malin, 2015). Whereas the Connected Arts Learning framework is general about the setting in which arts learning happens, we define CCYA programs as community-based youth development spaces that have a role in larger learning ecosystems. Our definition of CCYA emphasizes the importance of the learning context being rooted in communities and the artists and organizers who are connecting within those communities. Aligned with Connected Arts Learning, CCYA learning experiences utilize those relationships and tap into young people’s interests.

6. Culture-Centered

Flow Academy offers a vibrant array of workshops rooted in hip-hop arts and culture, including DJing, graffiti art, emceeing, and breaking. Flow Academy centers youth voice and supports youth-led action. For example, the program empowered participants to lead a campaign—complete with a music video on YouTube—advocating for changes to local school dress code policies. Through engaging artistic and learning experiences, young people at Flow Academy explore history, culture, and their own identities.

Culture has been conceptualized in various ways, and it is important that researchers provide clarity in the use of culture as related to the research focus (

Minkov, 2013). In using “culture-centered” as a component of CCYA programs, we adopt an approach to understanding culture as aligned with racial and ethnic identity (

Worrell, 2014). Broadly, culture includes the customs, arts, social institutions, socio-historical priorities, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or other social group. Art is a representation of culture and provides the tools and symbols necessary for cognitive development and is useful in the identity development process. Culture is meaningful, as it can have emotional, experiential, and instrumental value—especially for those connected to non-dominant cultural identities in the U.S. CCYA programs might center cultural identities linked to African American/Black, Asian American/Pacific Islander, Indigenous, Latinx, Middle Eastern, and Native American experiences in the U.S. Often, due to cultural affinity, culturally specific art forms, and the racialized patterns of segregation, CCYA programs primarily serve youth from a single racial/ethnic community. Though CCYA programs affirm the racial/ethnic identities of youth of color served in the program, they also invite young people to learn about genres of art that have roots in diverse cultures. For example, a program might teach hip-hop dance to Latinx youth, emphasizing the role that Black art expressions have in our society. The centering of culture becomes an avenue to consider a range of artistic expressions in a way that acknowledges the presence and contributions of people of color. The process of creating art in CCYA programs is a communal experience, often intergenerational, and can be healing for participants. The following paragraphs discuss three ways that CCYA programs might center culture, based on adopting an approach that is catered towards youth of color.

6.1. Highlight the Culture

Firstly, culture-centered youth programs intentionally highlight the experiences, contributions, and futures of people of color, both in the U.S. context and globally. They celebrate culture by placing high value on the contributions and expressions of people of color. Therefore, CCYA programs “center” (or prioritize) the identities, experiences, and needs of youth of color. Importantly, culture-centered programs maintain a connection to racial and ethnic communities in a local ecosystem, supporting mutuality between the community and the program. In centering youth, their identities, and their communities, CCYA programs celebrate the cultural wealth and expressions reflected in communities. In being culture-centered, CCYA programs are culturally responsive in a way that is distinct from what might happen in schools. Art uniquely represents culture in a way that does not necessarily apply to academic subjects. Culture-centeredness, by definition, does not necessarily only teach what we might see as cultural genres of expression. A CCYA program could teach classical music but highlight Black classical composers and expose youth to classes taught by experts who are people of color. CCYA programs do not limit youth to certain genres or ways of performing art. Instead, they may train across a broad scope of artistic forms, providing opportunities for young people to add their unique contributions across forms of creative expression.

6.2. Emphasize Equity

Secondly, culture-centered programs also center equity by intentionally serving youth who are marginalized by emphasizing access and opportunities to youth who experience marginalization due to race. This intentional equity focus is a key characteristic of the culture-centered experience, which centers the identities, experiences, and needs of youth of color. Black and Latine youth are least likely to have arts exposure in their schools. Additionally, many art forms have financial costs that could be prohibitive to youth in racialized, socioeconomically segregated neighborhoods. Many youth in CCYA programs are enthused about the learning opportunities and materials (such as cameras, musical instruments, and pastels) they gain access to. To reduce disparities, organizations often offer free programs or even pay students to attend. Many also address transportation barriers by delivering programs at schools or providing rides through teaching artists’ personal vehicles or purchasing a van. These moves have costs yet communicate a commitment to eliminating participation barriers.

6.3. Affirm Youth Identities

Finally, culture-centeredness empowers youth to see themselves and see our world in ways that both affirm and humanize their identities. Power, at its core, is influence. These programs, which support students’ development of critical consciousness, operate in culturally sustaining ways (see next section). One of the ways CCYA programs empower youth is through representation—allowing them to see themselves reflected in program leadership roles. In many sites, part of creating a safe, culture-centered, space is intentionally hiring staff members with the same background as youth participants. This is power shifting. For many youth of color, the teaching staff at their school is overwhelmingly White, as the teaching force is about 80% White (

Carter, 2021). A different narrative in CCYA programs allows youth to interact with and learn from adults who may have similar racialized and ethnic experiences, communicating potential for access to power and privilege. A second way culture-centered programs empower youth is by embracing a social justice lens on issues youth may see in their communities and our broader world. Many programs use art as a context for engaging in critical dialog about power and oppression. This practice, considered critical youth development, is necessary and beneficial for youth as they navigate racialized power realities and their impact on their lived experiences. Representation and critical youth development are two examples of culturally sustaining practices that guide how CCYA programs engage with youth of color.

6.4. Connections Between Well-Being and Culture-Centered

Culturally sustaining pedagogy (

Paris, 2012;

Paris & Alim, 2014) is a strengths-based framework that enhances our understanding of optimal learning and engagement for youth of color. Though the framework typically applies to learning in school settings, the benefits of culturally sustaining approaches can be extended to arts-connected out-of-school time learning (

Baldridge et al., 2024). Culture and art are deeply interconnected, and all learning is a cultural experience (

Nasir et al., 2013). Accordingly, culture can serve as an anchor for arts education for youth of color (

Akiva et al., 2024). Folklórico dance, rooted in Chicana culture, has been described as a tool for empowerment that supports youth’s critical consciousness, addresses historical oppression, and centers culture and well-being (

Salas, 2017;

Torres, 2022). CCYA programs view the arts as a means to foster students’ critical consciousness and address social justice issues relevant to marginalized communities (

Love, 2019).

Ibrahim et al. (

2022) found that high involvement in the arts was linked to the development of critical consciousness, particularly among youth of color. A review by

Maker Castro et al. (

2022) identified associations between critical consciousness and well-being for youth of color. Our study highlights that culturally sustaining practices in arts education manifest in various forms that support the identities of youth of color and ultimately promote their well-being.

7. Future Research

Future research should use multiple methods to understand the role that culture-centered, community-based youth arts programs play in supporting well-being for youth of color. Researchers should use an empirical approach to understand the ways that our theorized connections appear or do not appear in the context of program activities. This might include using program observations, experience sample measurements, surveys, interviews, and focus groups to gain clarity on the mechanisms through which community-based youth development, high-quality arts, and a culture-centered approach enhance well-being for participating youth. Studies might use these methods to gauge the experiences and perspectives of youth, teaching artists, program leaders, and community members. Based on the PERMA framework described above, some questions to understand the link between well-being and the described components of culture-centered, community-based youth arts programs.

How does involvement in arts support experiencing positive emotions, as a component of well-being?

Does arts involvement help youth release negative emotions?

Do CCYA programs support a sense of belonging for participants? If so, through what mechanisms?

Does CCYA differ in important ways across types of art (e.g., dance, music, visual, theater)?

How do more individual vs. more group art experiences differ in CCYA?

How do relationships in the context of youth arts programs lead to positive outcomes for youth?

How does learning in the arts support the development of feelings of achievement or skill-building?

How do culturally sustaining youth arts program experiences support meaning and identity development?

What does purpose look like in the context of culture-centered, community-based youth arts programs?

8. Conclusions

CCYA programs represent a potentially optimal developmental space for arts-interested youth of color, supporting thriving and identity formation. A recent review indicates a connection between arts and resilience for marginalized young people, suggesting that the arts support the health of society and are also important for individual well-being (

MacDonald et al., 2020). Arts programs can support sociopolitical consciousness for marginalized youth (

Ngo et al., 2017). Arts learning, therefore, can be a liberatory form of education that advances equity and justice. Many knowledge gaps exist related to such potential benefits of arts involvement. Though some have documented the benefits of arts on health and well-being, researchers have not given the same degree of empirical attention to possible benefits of arts involvement that are more aligned with the need to address the health and well-being of youth of color through a culture-centered lens.

Culture-centered, community-based arts programs integrate the best of youth development practices with creative learning and culturally sustaining approaches. For participating youth of color, the result is an opportunity to belong, to be seen, and ultimately to become. Experiencing CCYA supports well-being as youth find pathways to future possible versions of themselves. Well-being in the present moment looked like being connected in the creative community and learning skills through the arts, all while being meaningfully affirmed in their identity. The number of hours and amount of resources CCYA programs put into serving youth and communities of color represents a strong commitment to enhancing equity. In summary, the PERMA well-being framework (

Seligman, 2018) provides an overarching understanding of psychosocial well-being and its relevance to the experience of young people in CCYA programs.

Eisner (

1998) and

Greene (

2013) underpin our understanding of high-quality arts learning. The Connected Arts Learning Framework (

Peppler et al., 2023) corroborates the value of creative pathways in arts learning ecosystems. The Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy approach (

Paris, 2012) contributes to our centering of culturally sustaining learning through the arts. These interconnected frameworks lay a foundation for our understanding of youth well-being in the context of culture-centered, community-based youth arts programs.