Abstract

Young people are frustrated and disheartened with the lack of adult leadership and action to address the climate crisis. Although youth representation in global, regional, and local decision-making contexts on climate change is steadily growing, the desired role and effect of youth in environmental and climate decision-making has shifted from a focus on having youth voices heard, to having a direct and meaningful impact on policy and action. To meaningfully integrate youth perspectives into climate policies and programs, intergenerational approaches and youth–adult partnerships are key. This paper explores strategies to support youth action and engagement as adult partners by investigating youth perspectives on what adults and adult-led organizations should consider when engaging young people in climate-related work. This qualitative research study introduces a revised version of the 7P youth participation framework, developed through focus groups with high school youth. This paper provides reflective questions and practical recommendations for participants engaged in youth–adult partnerships to help guide engagement beyond token representation and create meaningfully participatory conditions for youth agency in climate organizing spaces.

1. Background

Young people from around the world are increasingly participating, advocating, and voicing the need for urgent, science-driven climate action. Collecting inputs from over 700,000 children and youth, the Global Youth Statement (YOUNGO, 2023), presented at COP28 in Dubai, reflects widespread frustration with current leadership and demands the use of the “best available science to guide ambitious climate action”. Additionally, the Global Youth Statement (YOUNGO, 2022) presented at COP27 urged Parties to “take heed, take charge, and take action” as children and young people identified the urgency and mounting crisis: “We have no more time to lose. Our future literally depends on it” (p. 2). Similarly to Global Youth Statements presented at the last two COPs, that advocate for children and young people’s perspectives to be integrated into formal policy-making processes, the Driving Ambition Manifesto developed by Youth4Climate (2021) stresses the importance of a multi-stakeholder approach, engaging not only youth but also racialized and Indigenous communities. It calls for cross-sector collaboration as well as advocates for education systems that are responsive to truly empowering young people. Additionally, there is growing demand among young people for climate policies that secure their constitutional right to information and preparedness regarding climate change and its impacts, as evidenced by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment (2023) for the implementation of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child. Frustration of climate inaction by young people is also evidenced in the 34 youth climate cases being adjudicated worldwide (UNEP, 2023), and high rates of climate anxiety experienced by young people globally (Hickman et al., 2021; Galway & Field, 2023). Beyond this, racialized youth climate activists face a dual burden, not only advocating for their communities’ rights but also navigating internationalized oppression and reflecting on their own practices amidst the very systems they fight against (Grewal et al., 2022; Lowan-Trudeau, 2018). Young people’s perspectives matter in climate policy because they represent the generation that will face the most significant and long-term impacts of the climate crisis and youth climate activists often identify the importance of systemic and justice-focused transformation over incremental changes (Karsgaard & Shultz, 2022).

In Canada, about half of young people (48%) learn predominantly about climate change through teacher instruction (Field et al., 2019), but increasingly schools are falling short of fostering the capacities young people need for addressing the complexities of the climate crisis (Stein & Andreotti, 2021; Richardson, 2024; Robinson & Parker, 2024). There is strong empirical evidence that a young person’s sense of efficacy and their engagement in social groups that support acceptance of climate change are strong predictors of pro-climate mitigation behaviours (Busch et al., 2019). With this in mind, the question arises whether education is fostering climate leadership among young people or are educational structures stuck within agency-limiting constructs of how young people can engage in meaningful social and pro-climate community learning and service work?

This research is part of a capacity and networking building initiative wherein a university worked with an Environmental Youth Council (anonymized, and referred to as EYC from hereon) to host a high school sustainability summit at a university in Ontario, Canada. A SSHRC Connections grant supported this initiative and provided a platform for young people to design the day-long event focused on sustainability and climate issues that they identified as important, and to explore actions and workshops they wanted to see addressed in their schools. The summit engaged 185 high school students from the surrounding community in the activities coordinated and designed by the EYC. This study illustrates challenges and successes of a youth–adult partnership, primarily using Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) framework, and highlights key considerations for fostering meaningful and intentional youth-adult collaborations in climate justice initiatives.

2. Youth–Adult Engagement: Definitions, Examples, Gaps, and Possibilities

This literature review explores key themes related to youth–adult engagement, including foundational definitions and forms of participation, challenges to adultism and strategies for fostering intentional relationships, the transformative potential of youth–adult partnerships, the risks of disempowering practices, and the conceptual framing offered by Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) youth–adult partnership model.

2.1. Definitions and Types of Youth–Adult Engagement

Youth–adult engagement has been studied across diverse contexts, with varied approaches for facilitating and evaluating its effects. These approaches differ based on age groups and settings—for instance, strategies for high school students may not align with those for post-secondary youth or young professionals. A broad range of models appear in both academic and practice-based literature, including youth–adult partnerships [Y-APs] (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018; Hall, 2020; Howell, 2023); youth participatory action research [YPAR] (Bettencourt, 2020; Hall, 2020); youth organizing (Hall, 2020); and youth empowerment frameworks (Susskind, 2010; Mohajer & Earnest, 2009).

This study focuses on high school youth and centres Y-APs—defined as collaborative, democratic engagement between multiple youth and adults working on shared projects aimed at promoting social justice, strengthening organizations, or addressing community issues (Hall, 2020; Howell, 2023). In Y-APs, youth and adult voices should be equally valued and relationships characterized by mutual respect, balanced power, and meaningful collaboration (Arokiasamy et al., 2023; Boys and Girls Club of America, n.d.; Oliver, 2010; Weybright et al., 2016; Zeldin et al., 2013). While not the focus, it is helpful to distinguish Y-APs from related models. YPAR positions youth as co-researchers from the outset of the project, using action-oriented methods to identify, analyze, and take action on issues that impact them and their communities (Bettencourt, 2020; Hall, 2020). In this study, university adult-partners followed the leads of youth organizers, but did not engage youth in action-oriented research methods. This study more closely aligns with youth organizing; a youth development and social justice approach that provides young people with peer-led education and training on organizing and advocacy to challenge power relations and galvanize meaningful change (Hall, 2020). This model emphasizes peer-to-peer learning and collaboration, which corresponds to the youth-led sustainability summit and collaboration with adult university partners. Lastly, youth empowerment is defined as an increase in the capacity of youth to create change in their community and within adultist systems (Susskind, 2010). It is an ongoing process and extends beyond single events like the summit and includes developing knowledge and skills, critical awareness, strategic building, and leadership skills, relationship-building, and engaging in action (Susskind, 2010).

2.2. Disrupting Adultism as an Approach to Intentional and Meaningful Youth–Adult Partnerships

To disrupt adultism, youth and adults must work together to foster equitable relationships and approaches that challenge and mitigate adultism; such efforts yield benefits for youth including enhanced leadership skills, a stronger desire to contribute to community change, a greater sense of control over their lives and the world, and improved self-esteem and agency (7 YF Principles, n.d.; Hall, 2020; Watson, 2024). Youth insights and contributions should therefore be recognized as relevant and meaningful in the present rather than deferred until they have “grown up” (Aleks Mingsheng, 2022; Shaw-Raudoy & McGregor, 2013).

However, the degree of youth engagement in decision-making processes varies significantly, and adultism often constrains meaningful participation. Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Citizen Participation offers a foundational framework for understanding these power dynamics, illustrating how participation ranges from tokenistic consultation to genuine citizen control. Though developed in the context of broader civic participation, Arnstein’s model has informed discussions on youth engagement, illustrating how adult-led approaches can reinforce symbolic or tokenistic inclusion. Building on this, Hart’s (1992) Ladder of Youth Participation provides another ladder framework to examine how institutions and professionals engage young people. Hart’s model has been instrumental in helping educators, youth workers, and policymakers assess the degree of authentic youth involvement in decision-making. The framework highlights the risks of adult-driven participation that inauthentically engage youth and calls for deeper more equitable forms of youth participation.

Karsgaard et al. (2022) build on these frameworks by situating youth participation within advocacy education, emphasizing the necessity of moving beyond prescribed, adult-controlled actions toward forms of engagement that allow youth to exercise agency in shaping social, economic, and political conditions. Drawing on Botchwey et al. (2019), Karsgaard et al. critique projects that position young people as passive actors whose participation serves predetermined outcomes—often designed for behaviour management or individual development rather than systemic change. Instead, genuine advocacy requires an ethical commitment to shared power, where youth take space for themselves and engage adults as partners in change. By conceptualizing advocacy as a transitional rung between consent and full incorporation in decision-making, Karsgaard et al. challenge educators to design learning experiences where youth advocacy is not merely an exercise in civic engagement but an authentic means of challenging injustice.

As such, disrupting adultism requires shifting power within decision-making to value the knowledge and skills of young people and centre youth lived experiences in decisions, policy, and actions (7 YF Principles, n.d.; Aleks Mingsheng, 2022; Students Commission Canada, 2023). Authentic engagement, where youth have power (citizen control vs. delegated power (Arnstein, 1969)) also disrupts adultist processes that tend to reward compliance and adherence to predefined “youth” roles, marginalizing or pathologizing youth who challenge the status quo or critique existing systems of power (Liou & Literat, 2020). Interrupting adultism also requires valuing and integrating youth capacities and literacies into educational frameworks and climate change discourses.

In summary, Y-APs are most meaningful when adults actively listen and affirm youth experiences, educate themselves on relevant issues before intervening, support youth in pursuing personal and professional growth, contribute specialized skills or knowledge to advance youth-led goals, and act in solidarity with youth and youth movements (Liou & Literat, 2020). This includes recognizing the unique expertise youth activists bring and amplifying the cultural and creative dialogues they lead (Bowman & Germaine, 2022). Table 1 outlines several examples of intentional and meaningful Y-APs in Canada, aligned with levels of youth participation and power. The youth–adult partnership detailed in this study took place in Ontario, Canada, and as such, we selected examples in similar socio-political contexts to understand the background of Y-APs and their relevance.

Table 1.

Select examples of Intentional and Meaningful Y-APs.

2.3. Youth–Adult Partnerships Critical for Transformative Change

For the purpose of this study, “transformative change” refers to profound shifts in societal systems and structures that move beyond incremental improvements. It requires fundamentally rethinking and reconfiguring power dynamics, relationships, and approaches to environmental and social issues in ways that are equitable long-lasting, multi-voiced, and multi-actor formations (Lotz-Sisitka et al., 2015).

In this context, transformative change can be driven by intergenerational partnerships. Youth and early-career professionals can bring interdisciplinary backgrounds, fresh perspectives, and innovative ideas that help generate novel solutions to complex global challenges, like climate change (Jeunesse Acadienne, 2017; Lim et al., 2017). Intergenerational relationships and empathetic dialogues are critical in the building of communities that are collaborative, equitable, resilient, and culturally responsive to more stabilized futures (Hayes et al., 2023; Susskind, 2010; Zurba et al., 2020). Intergenerational partnerships can help foster transformative change by bridging youth creativity in imagining possible futures and better worlds, adult capacities for implementing change, and seniors/elders’ abilities to bring in their lived experiences and provide insight on plans of action (Kennedy & Gislason, 2022; Zurba et al., 2020). These intergenerational collaborations are more likely to lead to solutions and action that are more meaningfully integrated across sectors and grounded in equity-focused approaches (Kennedy & Gislason, 2022).

Therefore, climate and environmental policies and frameworks should integrate official and continuous mechanisms for intergenerational dialogue, collaboration, and co-learning within their processes and actions (Zurba et al., 2020). Youth-led activist movements often inspire greater positive change than their adult counterparts because they are more open to collaboration and listening and learning from each other’s experiences (Liou & Literat, 2020). Climate strikes led to transformative literacies that work to transform communities by improving the conditions and participation of community members in making changes happen by supporting solidarity and relationship building among members (Bowman & Germaine, 2022). The youth climate movement is grounded in visions that integrate climate and social justice, advocating for systemic change and standing in solidarity with movements such as Black Lives Matter. It places strong emphasis on anti-racism and decolonization (Grewal et al., 2022; Elsen & Ord, 2021). In this study, we drew on literature connected to social justice and Y-APs to respond to the intersectional focus of youth organizers.

This is illustrated in Larocque’s (2023) explanation of the theory of social-ecological transition in the context of youth climate organizing. This theory demonstrates climate change as a systemic issue that is influenced and interconnected within social processes, exemplifying the inextricable link between environmental and social justice issues (Larocque, 2023). In contrast to past models of socio-ecological transition, the youth eco-activists centred the socio-cultural pillar as the more integral component of socio-ecological transition, particularly highlighting intersectional climate justice, intergenerational solidarities, and place-based connections wherein almost all social and environmental causes can be linked together by their roots in the same colonial, capitalist, racist, homophobic, ableist, and extractivist system (Larocque, 2023). We have addressed the positive benefits of Y-APs in this section thus far, but Y-APs are not always positive and can reinforce adultism and disempower young people.

2.4. Disempowering/Harmful Youth–Adult Collaboration Practices

Adults and older generations are more likely to act within the status quo, adhering to existing power structures; whereas, youth tend to resist incremental change and push for transformative change (Clay & Turner, 2021). Youth experiences of structural and systemic inequities and the challenges that they face in enacting change within a society may lead to feelings of hopelessness and burnout (Nairn, 2019). Many young people report feeling a disproportionate burden to address climate change due to what they perceive as widespread societal negligence (Nairn, 2019). The work itself can be emotionally and physically exhaustive as climate activism is frequently experienced as unending and all-consuming (Gorski & Chen, 2015).

Interpersonal dynamics between youth and adults can lead to disempowering or harmful interactions. Decision-making spaces typically reflect adult-centric structures that can alienate, discouraging collective organizing and action among youth and between youth and adults (Aleks Mingsheng, 2022). Youth may also struggle to navigate logistical barriers such as accessible meeting formats, incompatible communication styles, and transportation or scheduling limitations. (Weybright et al., 2016). Moreover, adults may rely on corporate or technocratic language that can obscure or undermine youth visions for justice and change and dilute the potential for more radical, systemic change (Clay & Turner, 2021). To build inclusive and supportive spaces, cultural sensitivity and anti-oppression training for all youth and adults involved in a partnership will improve the accessibility and safety of the space (Arokiasamy et al., 2023). Without this, poorly executed Y-APs can reinforce and reproduce paradigms where those who have less power are silenced and tokenized (Clay & Turner, 2021). The generational divide, particularly evident in the context of climate activism, can perpetuate adultist and colonial dynamics that undermine meaningful intergenerational collaboration (Lam & Trott, 2024). In contrast, many Indigenous practices integrate all generations, valuing contributions of community members of all ages in environmental care and ways of knowing (Lam & Trott, 2024).

Misconceptions about youth further inhibit equitable collaboration. Young people are often dismissed or punished when their activism challenges societal norms, and they are frequently stereotyped as naïve or irrelevant (Bell, n.d.; Blanchet-Cohen et al., 2013; Ayalon & Roy, 2023). These attitudes, compounded by a lack of genuine respect for youth perspectives, can result in condescending or belittling treatment.

Finally, seemingly empowering forms of inclusion can be superficial. Tokenizing remains prevalent in climate organizing spaces, where a few individual youth are expected to speak on behalf of their entire generation. This isolates young participants and contributes to burnout, particularly when their involvement lacks real influence (Climate Strike, 2019). While youth may be celebrated as symbols of inspiration, they are often excluded from substantive decision-making roles (Aleks Mingsheng, 2022). Such performative inclusion reflects a deeper failure to recognize youth as legitimate agents of change (Susskind, 2010).

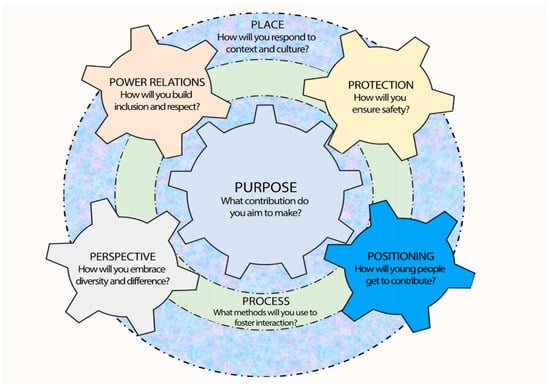

2.5. Y-AP Conceptual Framework for Youth Participation

Building on past models of Y-AP, Cahill and Dadvand (2018) developed the 7P conceptual framework for youth participation (see Figure 1). Past models of Y-APs and youth participation operated with the assumption that youth participation was a straightforward process that resulted in positive outcomes for youth by providing a voice for youth and opportunities to have agency that would ultimately lead to empowerment (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018; Lund & Beers, 2020). The 7P model accounts for some of the more complex and in-depth components of youth participation in decision-making to illustrate the components that are essential for developing meaningful youth–adult collaborations. The 7Ps are purpose, power relations, perspectives, position, protection, process, and place (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018). The 7P model is applicable when considering youth–adult collaboration for a specific initiative, program, or research project and supports adult allies in examining their own preconceptions and assumptions to encourage positive adult partnership (Barg, 2022). Following Thew et al. (2022), who revised the 7P framework and recommended a consideration of psychological factors in the Y-AP, we have integrated that into the research design.

Figure 1.

Cahill and Dadvand (2018) 7P framework: a thinking tool for visioning, planning, enacting, and evaluating youth participation.

3. Methodology

Study Context

This research focuses on an Environmental Youth Council [EYC] and a summit they organized with support from adult-partners at a local university in Canada. The EYC is a youth council made up of representatives from three regional high schools. While the council operates independently, its president serves as a liaison by attending the adult board meetings of the larger ENGO with the same name, ensuring youth perspectives are integrated into organizational decision-making. The EYC took the lead in planning and executing a one-day event in spring of 2022, with support from the adult board. The summit was attended by 185 high school students from regional high schools, while adult partners at the university provided mentorship, logistical support, and funding. University partners facilitated bi-monthly check-ins in the first six months with EYC members and bi-weekly meetings in the last six months leading up to the summit. The university partners assisted with administrative processes and ensured the youth retained decision-making power. At the EYC’s request, teachers attended separate professional development workshops, allowing students to fully engage in youth-led discussions and activities.

This study follows a qualitative research design using focus groups to explore youth perspectives on youth–adult partnership and responsive educational approaches for addressing climate and sustainability challenges important to young people. The youth participants aged 16–19 from the EYC were invited via email to participate in a 90 min focus group, reflecting on their experiences organizing the youth-led sustainability summit and working with adult partners. These youth intensively worked together as a team to organize and run the sustainability summit; therefore, interviewing the team as a group was appropriate to hear their collective reflections on their experiences. Seven youth from the EYC were available, paid a $40 honoraria, and all completed informed consent forms prior to participation. This study received approval from the Lakehead University Research Ethics Board.

Focus groups were conducted virtually via Zoom. The focus group centred on the primary research question: What is the nature and process of youth–adult partnership in creating participatory learning experiences that address climate and sustainability challenges? Specifically, youth were asked questions on lasting impressions of the summit, experiences in working with adults on climate projects, in what ways or where have they experienced effective Y-APs, description of qualities or processes that have created conditions for an effective Y-AP, and recommendations to adults on how to work with youth. Audio recordings were transcribed, and participant confidentiality was ensured. Data was analyzed through thematic inductive coding to develop an iterative coding tree related to salient themes (Miles et al., 2020). One of the authors was directly involved as a university partner supporting the EYC and attended meetings, while the other was not directly engaged with the EYC or the summit coordination. To mitigate bias, the author not involved in the partnership took the lead in data review and analysis, creating a more balanced interpretation of youth perspectives. After the initial coding process or first cycle of coding using Dedoose, the research team engaged in collaborative discussion to further interpret and synthesize the data. This inductive phase was then followed by a second deductive phase of applying the codes to the 7P framework (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018), synthesizing theory with youth perspectives from which an adapted 7P framework has resulted. To ensure consistency in coding, both researchers independently applied the codes to the 7P framework and compared interpretations. A summary of findings was circulated to participating EYC members for review.

4. Findings: Applying the 7P Framework

In this study, we applied the 7P framework to understand the processes and experiences of youth in the EYC group as they collaborated with an adult-led organization to co-develop a sustainability summit for high school students in their region. We begin by outlining the components of the 7P framework developed by Cahill and Dadvand (2018) and integrate findings from other studies that have applied this framework to Y-APs. For each domain, we detail how youth perspectives from focus groups aligned with these elements. In the Discussion section, we present an adapted 7P framework based on this synthesis to respond to the context of Y-APs in climate justice organizing—specifically focusing on the urgency of action on the climate crisis, and the mental and emotional tolls of climate organizing on youth.

4.1. Purpose

A co-developed purpose can lead to youth experiencing a sense of ownership over the project, and ensure that the programs/campaigns are culturally, socially, and personally relevant for youth participating (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018). There are two purposes that we speak to in the context of this study. The youth involved with EYC were involved in two Y-APs: one, on a short-term basis, with the adult partners at the university that supported their sustainability summit; and the other, on a longer-term basis, as the youth advisory council for a local environmental non-profit organization (ENGO) in their community. The shared purpose between the adult university partners and the EYC was to organize and host the one-day summit for high schoolers across the region to provide opportunities for education, engagement, and action on climate and environmental issues relevant to their communities as well as networking opportunities among youth and with environmental professionals. The EYC and the local ENGO shared the purpose of supporting their city in increasing sustainability awareness and initiatives, a long-term collaboration. This sense of purpose with organizing the summit was shared by several youth organizers in the focus group: “It was a formative experience for me. I’ve never really had a chance to be a part of something like that…on such a wide scale…I’m really proud of what we did” and another youth shared “I think that seeing almost 200 students from across a school board come together for one common cause was definitely….was definitely nice! I think we pulled it off decently.” However, youth conveyed some confusion about how the youth council should work with the wider ENGO:

We would be receiving emails about every single thing that pertains to the Board, even though there’s 5 or 6 different working groups within the organization, and we are only responsible for the youth council. We were flooded with all of these emails that we didn’t know what pertained to us and what didn’t pertain to us. And then we would end up missing things that they were actually asking us.

4.2. Positioning

Within the 7P framework, positioning focuses on the ways that young people are understood and portrayed in society, and what is expected of them, i.e., their positioning. In the context of a Y-AP, this involves clearly outlining the roles of young people and considering how those roles relate to the adult partners in an effort to improve youth participation and engagement (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018). For this research study, the sustainability summit was led and directed by the EYC youth, with adult partners offering logistical and administrative support through biweekly check-ins with adult organizers. Youth were responsible for determining content, coordinating with speakers, and managing the event’s flow. This structure fostered a sense of agency among youth, as participants reflected: “We also got to have the chance to run one of the workshops…and I just really liked the experience of working with like-minded youth” and another youth shared “when we all met at the venue, and we were getting everything ready that it was actually going to happen, and seeing it all come together on the day of versus just an idea from the group that was really really cool.”

Despite their leadership, some youth expressed feelings of stress and responsibility, particularly during the final stages of planning. As one youth described, “The last two weeks, I was kind of afraid, because…being the main receiver of all the emails…was a little bit nerve-wracking.” This sentiment highlighted the dual nature of their role: empowering yet challenging for them with their skills and experience. Additionally, the youth noted that the summit’s impact could have been amplified if its outcomes had been integrated into classroom projects, suggesting a missed opportunity to extend its influence with teachers:

think it would have been really good to see teachers become more directly involved with their students’ projects and taking what they learned at the summit back into the classroom, and actually trying to run sort of like a small-scale project in their school community, or their greater community with their class where their teacher is helping more facilitate it, because that’s what we were trying to teach the teachers at the PD day and while the students learned a lot there weren’t exactly projects that we saw coming out from the summit directly tied to it.

In the context of the EYC’s role as the Youth Advisory Committee to the local ENGO; their president sits as a full voting member on the ENGO’s board of directors, and is expected to participate fully in board meetings and decisions. The Youth Advisory Committee as a whole provides input and direction to the ENGO and brings youth perspectives to their work.

A common theme that came up regarding the EYC youths’ experiences as the Youth Advisory Committee for the local ENGO and within climate and environmental circles in general was:

one thing that sometimes can be found is the tokenization of youth in the sense that adults will use you purely for forwarding or furthering their agenda, and like making it seem to you that, you’re doing what you need to do, and you’re doing great, but once it really does get down to it they’re really just using you as a prop for whatever they need to get done.

They also spoke to the fact that meaningful youth engagement is critical in the context of climate change, as

what is being planned today surrounding climate change might not be applicable in 30 years. In fact, it probably won’t be applicable in 30 years and might not be applicable next year. So the concept of bringing youth into that discussion, I think, is really important, because we are going to make some plan moving forward for the future. The people who are going to be leading that plan, when it’s most needed, should really have a say in how it’s going just to ensure that it can still be functional, and it does still apply.

Overall, the position of the youth in their roles organizing in the climate space generally differed between contexts. In the context of the sustainability summit, the EYC youth were in a leadership role, leading the direction, content, and organization of the summit. In other contexts, however, including as the Youth Advisory Committee for the local ENGO, and more broadly, they have experienced tokenization and a lack of decision-making power.

4.3. Perspectives

In terms of perspectives, participants must account for the diversity of lived experiences and cultural identities that exist within groups and among individuals of young people (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018). Taking perspectives into account includes actively working to meaningfully engage youth of diverse ethnic and racial identities, genders, sexual orientations, (dis)abilities, and socio-economic class in the work. In this research study, the youth organizers represented the executive leadership of the EYC, a group selected through internal nominations. The adult partner organization was approached by the existing executive of the EYC for support in organizing the summit. Throughout the planning of the summit, the EYC showed a strong commitment to including diverse perspectives within the summit’s workshop offerings.

4.4. Power Relations

Power is relational, shaped by how individuals are positioned in relation to one another (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018; quoting Foucault, 1980). When considering how adults and youth can collaborate intentionally and meaningfully together, it is crucial to address underlying power imbalances that often place adults in dominant roles. These dynamics may also exist among youth themselves, influenced by factors such as gender, class, ability, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and more.

In this research study, the EYC youth and the adult partners in organizing the summit operated with a balance of power and responsibility that were shared between the youth and the adult partners. However, given that the youth were leading the organizing process, they had to navigate interactions with adult professionals and social contexts, and they were met with some challenges. One of the youth shared that it was “the first time I had ever had to work with any kind of professional before so emailing back and forth and I did planning with one of our workshop leaders as well, so that was an interesting aspect, working one on one with somebody.” The youth spoke of this as an empowering experience that they learned from and felt that they had influence over, but also experienced some challenges, for instance,

there were maybe some issues contacting people. Since I had one of our representatives to contact, there were some difficulties trying to get a hold of him and maintain a conversation. There was sometimes a long waiting period to get responses back. So I think maybe given the fact that it was coming from a student organization, sometimes things do get pushed back a little bit just in terms of prioritization, but overall I think it was actually a very positive experience.

Conversely, significant power imbalances were evident in the youths’ relationship with the ENGO board. Youth recounted feeling undermined and criticized by board members, particularly when their efforts were misinterpreted or dismissed. One participant described receiving an email that “felt like a bombardment of suggestions,” which exacerbated feelings of stress and burnout. As the youth explained:

It was like a very long email, pretty heavy-handed [from board]...And there’s this long list of things that we weren’t doing right according to the board and that we were like letting them down essentially…They were also completely ignoring all the work that had [been] done. And they were saying that we were ignoring money that they gave us and mismanaging it, and we were not coming to board meetings, and we were not being as active as they wanted us to be. The email ended saying that they had done a legal review and if things did not change immediately, they were going to think about dissolving the Youth Council out from under us.

In this case, the local organization misused their position of power to criticize and threaten the youth leaders, without considering the challenges they were facing in participating fully in the board’s scheduled meetings.

Another youth reflected on how challenging it can be to work with adults and to be treated or feel themselves as equal:

So if you’re working with an adult on a level that you’re supposed to be equals, then decisions at some point need to be made as equals on both sides. I do think that the interactions often fall back into again, that school type, archetypal relationships between an adult and a young person that kind of lasts until you exit school and you have a job and money, and the money is a factor of it too, because you can’t plan things without money.

Another youth reflected on their overall general experiences working with adults on climate projects:

For the times that I have worked with adults on projects, I think it’s just overall been positive. I think the adults that work within climate change, or you know, sustainability usually are really supportive to youth, being a part of it as well and really encouraging. I felt that I’ve been treated fairly equally.

4.5. Protection

Youth experience some level of risk by participating in youth–adult relationships and community projects, as a result it is important to consider what protection is provided for them. Protection may exist in the form of legal protection in the case of direct action and activism, as well as ensuring there are policies and methods in place to address conflict that arises between youth and adults and among youth in groups. The collaboration for the summit provided a protective structure for the youth, offering financial, logistical, and emotional support. This support reduced the risk of burnout and ensured the summit’s success, while also giving ownership, leadership, and decision-making authority to the youth organizers. As one participant explained, “It’s important for adults to help guide you through the process…allocating money for us to stay stable…really helps everyone out.”

However, the lack of institutional protections became apparent in the youth’s relationship with the ENGO board, as previous quotes have portrayed. The absence of conflict-resolution mechanisms left the youth vulnerable to undue criticism and unrealistic expectations, which negatively impacted their mental well-being and willingness to serve in youth volunteer positions.

4.6. Place

Youth participation within Y-APs occurs within numerous spaces/places. These may be virtual, physical, or social places. Taking place into consideration involves looking at how the spaces can be physically accessible to youth and how they might influence the comfort and willingness of youth to participate. The planning for the summit occurred on zoom and was coordinated based on youth organizers availability and breaks in their school day. The summit took place at a local university campus and included participants from diverse urban and rural high schools across the region. The in-person nature of the event during the COVID-19 pandemic posed logistical challenges, but the youth and adult partners successfully navigated these constraints. The board meetings for the local ENGO were either in person or on zoom and often were scheduled during times that the youth president had other extracurricular commitments and was not able to attend.

4.7. Process

The process refers to how youth participation and Y-APs are carried out, focusing on all stages of the project that youth are engaged (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018). In the 7P framework, it is emphasized that it is crucial to consider what methods will most meaningfully and equitably engage youth (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018).

The summit’s planning process was initiated by the EYC youth, who approached the adult partners at the university for support. Regular biweekly check-ins supported ongoing collaboration, during which adult partners provided resources and guidance as needed. The university’s administrative staff also supported venue-related logistics, ensuring a smooth execution of the event. This is supported by the following youth reflections: “I think that it’s important for adults to help guide you through the process of doing things such as securing money for their projects, allocate money for us to stay stable, something like how the researchers at the university helped us with securing money for the summit. It’s an effective adult-youth relationship in that case because it definitely helps everyone out” and “It was nice to have your opinion valued that way, because it’s not often.” One other quote from a youth participant highlights how the youth felt they were able to minimize adultism, which may be related to supports offered through the university Y-AP, as follows: “I think we did a good job in trying to minimize the amount that people would be unsure about us because of our age.”

4.8. Psychological Factors (Following Thew et al.’s, 2022 Recommendation for Inclusion in 7P Framework)

Thew et al. describe psychological factors as crucial in understanding how youth engagement and participation is stimulated, sustained, and played out in decision-making spaces in the context of youth attendance and participation in global climate negotiations. They identify that fear for the future, guilt, and other considerations motivate their activism and engagement in climate decision-making as well as the fact that that participation in climate decision-making led to burnout, frustration, sadness, distress, and emotional and physical tolls (Thew et al., 2022). In this study, the youth reported feelings of stress and burnout related to their organizing responsibilities and the subsequent conflict with the ENGO board they shared that they are “overwhelmed by the amount of things set up for [them]selves” and that they found similarly that, referring to their peers who were engaged in leadership and environmental activities, “those students and those kids their schedules are beyond busy”. The criticism that the youth received from the ENGO board led to them being “a little bit shocked…expectations that they had for students were unreasonable” coupled with the pressure of balancing school and extracurricular commitments, took a psychological toll on the youth. These experiences underscored the importance of providing emotional support and conflict-management strategies in Y-APs.

4.9. Positive Impact as an Addition to the 7P Framework

To build on the work of Cahill and Dadvand (2018) and Thew et al. (2022) on the 7P framework for Y-AP and contextualize the framework for climate related organizing spaces, we added an eighth “P” for positive impact. One of the most important factors for the success of a Y-AP in the context of this study was the meaningful impact and positive change that resulted from the summit, rather than youth engagement that was tangential or tokenistic. Since the original 7P framework (Cahill & Dadvand, 2018) was developed for engaging youth in health-related projects, the climate organizing space is a shift from a more individual health focus to collective climate action.

The youth reflected on the importance of supportive Y-APs to facilitate positive impact as follows: “Adults often say that our generation is going to be the one to come up with the solutions for climate change…I think that the youth have really good ideas, and we’re the ones who are going to have to be living with it. So, by working together with adults, we can kind of use our ideas to get put into action.” They also reflected on the roles of mutual respect and co-learning between adults and youth: “Adults, believing that they have as much to learn from us as we do from them, and then putting that into practice, listening to our ideas, and then using their higher place of power, like in schools and stuff, to allow our voices to be heard, which proves that our voices are valuable and are being heard.”

In contrast to facilitating positive impact, youth may also be tokenized and feel “used” in the context of their engagement in climate spaces. Youth participants shared their experiences illustrating that “The tokenization of youth in the sense that adults will use you purely for furthering their agenda, and making it seem to you that you’re doing what you need to do and you’re doing great, but once it really gets down to it, they’re just using you as a prop for whatever they need to get done. It happens in the climate [space] and everywhere.”

In Y-AP work for environmental and climate action, it is critical to also consider the broader context of the shared purpose. For youth to feel that their efforts are meaningful, there needs to be real impact as a result of their work (Climate Strike, 2019; Susskind, 2010). Fostering meaningful and impactful climate action through Y-APs not only empowers and builds skills and confidence, but also leads to more creative solutions, and facilitates co-learning among youth and adults (Kennedy & Gislason, 2022; Larocque, 2023; Lim et al., 2017). One youth shared, with respect to communications about climate change, “I think when there is more collaboration, it’s greater quality, content, and greater ability to have better advocacy in regards to climate change or any other topic.”

This study is a good example of disrupting adultism since the youth were given meaningful decision-making power and opportunities to lead the summit themselves, were viewed as knowledgeable actors by the organizational partners, and were engaged in teaching their peers about climate and environmental issues through their own experiences (Liou & Literat, 2020; Bowman & Germaine, 2022). They were also victims of adultism in the context of the conflict with the adult board as they were expected to adhere to the adult world and requirements for adult board members. This need for real impact and collaboration for specific and meaningful action was spoken to by the EYC youth.

5. Discussion

This study highlights both the strengths and challenges of Y-AP in climate organizing spaces. The sustainability summit organized by the EYC exemplified an empowering and meaningful collaboration, which highlights the potential of youth leadership when supported by an intentional Y-AP. After applying the 7P framework to youth reflections on the summit, it seems that the summit successfully fostered youth agency and demonstrated the importance of shared purpose, balanced power relations, and intentional positioning of youth within leadership roles but it was isolated to that one main event. However, in broader contexts, such as the relationship between the EYC youth group and the adult ENGO board they worked with/for, showed persistent challenges. Suggesting that long term partnerships may come with challenges of tokenism, power imbalances, or psychological strain, if youth participation is not facilitated in intentional and respectful ways. It also may be simpler to integrate best Y-AP practices into acute collaborative events, and conversely long-term youth adult partnerships may be more complex to sustain over the long run. These findings also highlight the critical role of adult partners in offering logistical, emotional, and institutional support while respecting youth autonomy.

The study’s results align with Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) 7P framework, and successful case studies of Y-AP in environmental and youth-organizing (Blanchet-Cohen et al., 2013; Schmitt-McQuitty, 2007; Weybright et al., 2016), reaffirming the importance of shared purpose and balanced power dynamics for successful youth–adult collaborations. However, this study expands on the original framework by introducing critical considerations that reflect the lived experiences of youth in climate organizing spaces. First, the emotional toll of organizing efforts (Lund & Beers, 2020) highlights the need to integrate psychological factors (Thew et al., 2022) into the framework, to ensure youth receive adequate support to mitigate burnout and stress. Second, the importance of real-world positive impact emerged as a salient theme, reinforcing existing literature on the need to move beyond tokenistic engagement (Susskind, 2010; Bowman & Germaine, 2022; Aleks Mingsheng, 2022; Howell, 2023) and provide opportunities for youth to take leadership roles and direct adults and youth peers within Y-APs (Blanchet-Cohen et al., 2013).

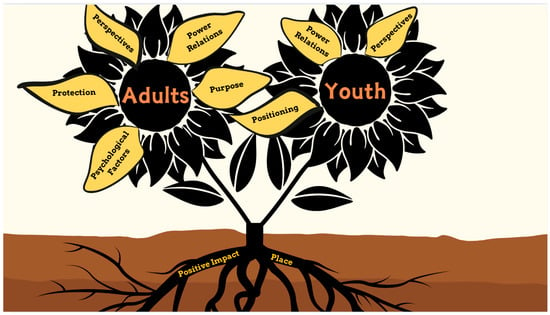

To illustrate these additions, we have adapted the 7P framework for the context of Y-APs in climate organizing spaces (see Figure 2). Most notably, we have reimagined the Cahill and Dadvand (2018) figure, replacing the gear motif with sunflowers, which are commonly used in climate justice work. Sunflowers were chosen as a symbol because as visual metaphors they more appropriately convey principles of interconnectedness, shared responsibility, collaboration and growth, whereas gears often symbolize mechanistic and transactional processes, which are not analogous with the organic, evolving, and relational nature of Y-APs or differentiated responsibilities.

Figure 2.

Adapted 7P framework for youth–adult partnership for climate organizing spaces.

This framework accounts for the shared and differentiated responsibilities between adults and youth, as well as integrating the value of meaningful impacts through the projects. In this updated model, we have highlighted that Y-APs should be authentically collaborative processes where youth and adults have equal roles in determining the purpose of the collaboration and projects, as well as the roles involved in the collaboration—shown with the overlapping petals for “purpose” and “positioning”. This adapted framework also builds upon established youth participation frameworks—Arnstein’s (1969) Ladder of Citizen Participation, Hart’s (1992) Ladder of Youth Participation, and Karsgaard et al.’s (2022) critique of adult-centric engagement. While earlier models emphasize degrees of participation and power-sharing, this adapted framework introduces additions grounded in the lived experiences of youth organizers, including the emotional toll of climate activism, the need for psychological support, and tangible outcomes of collaborations. We decided to depict responsibilities according to “adults” or “youth” because delineating roles helps address implicit power dynamics and these differentiated responsibilities of care and leadership will foster more intentional and effective youth–adult collaborations.

There are, however, some responsibilities that remain in the hands of adults, particularly when it comes to protection and psychological safety. These responsibilities are illustrated in the sunflower (see Figure 2), where they appear only on the petals of the adult’s sunflower. Adults in youth–adult collaborations have a duty to ensure adequate protections are in place for youth—logistically, emotionally, and physically—through thoughtful planning, attention to mental health impacts, and creating safe environments. While youth also need to adhere to these protective measures, the onus falls more heavily on adults due to the inherent power imbalance. Adults must not only create space for youth voice and leadership, but also proactively mitigate potential psychological harms that may arise from youth involvement in advocacy and organizing. Power relations must be navigated by both youth and adults, which is why power relations are represented on both petals of both sunflowers. However, adults carry a particular responsibility to acknowledge and help balance unequal power relations, even as youth must also be attentive to how lived experiences and identities shape their roles within these collaborative spaces.

The power relations of age are evident when considering youth–adult relationships, however, it is also crucial to account for the systemic barriers that both youth and adults face in participating in climate organizing. Both youth and adults share the responsibility of ensuring that a diverse range of voices are included in the project or program. In some contexts, where a partnership occurs through a formal youth advisory council body, there may be times where the adults have more authority over what and when youth are invited to the table, and therefore have more responsibility to ensure there are diverse perspectives in the space. However, there are also decision-making spaces where youth may run or organize their own recruitment/elections into these bodies, and as such they would have more responsibility to ensure there is diverse representation.

Finally, a key gap in looking at the 7P framework in the context of Y-APs for climate justice organizing is positive/real-world impact. Throughout the findings in this study, as well as many others (Bowman & Germaine, 2022; Liou & Literat, 2020; Nairn, 2019), intentional youth engagement in climate work should involve a meaningful contribution to climate action efforts, whether that be through decision-making, organizing events, or programming. Oftentimes, youth engagement is used to check a box and youth are disempowered by the lack of due consideration to their insight and opinions and feel that their participation was a waste of time (Augsberger et al., 2018; Clay & Turner, 2021; Thew et al., 2022). Intentional and meaningful Y-APs support youth to make contributions to decision-making and change making. Therefore, we placed the P’s of positive impact and place at the roots of the sunflower to symbolize how these elements provide foundational nourishment—ground the partnership in meaningful outcomes situated within context and community.

To apply the 7P framework to climate organizing with Y-APs, we adapted Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) questions for each “P” in this context (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Revised questions for 7P framework.

For additional literature on recommended practices for youth–adult partnerships see the supplemental file: Supplemental File—Recommended practices for Youth–Adult Partnerships.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of fostering intentional and meaningful Y-APs in the context of climate organizing. By applying and expanding upon Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) 7P framework, this research highlights the potential for collaborative initiatives to empower youth, support intergenerational co-learning, and result in climate actions. However, the findings also reveal persistent challenges, including youth tokenism, power imbalances, and the psychological toll on youth participants. Addressing these barriers requires adult partners to prioritize protections, balance power dynamics, and ensure that youth-led efforts focus on tangible climate actions.

The addition of positive impact, as an eighth “P” to Cahill and Dadvand’s (2018) 7P framework, highlights the value of real-world impacts as a grounding element of successful Y-APs in climate organizing. This addition reflects the growing demand for authentic youth engagement in climate justice initiatives, moving beyond symbolic participation to genuine collaboration that respects the lived experiences and expertise of young people, and that results in actionable outcomes.

Practically, organizations can use the revised framework as a planning and reflection tool, engaging youth in co-designing projects, evaluating their own engagement practices across the 8Ps, and building in safeguards to support emotional well-being and open communication. The sunflower model, and accompanying questions (see Table 2) can be used as a facilitation aid in training workshops or partnership-building exercises, to help map responsibilities, power dynamics, and shared goals.

This work offers a framework for cultivating transformative collaborations between youth and adults, grounded in mutual respect, shared purpose, and the pursuit of more stabilized and just futures, that are critical for responding to the threats of the climate crisis in turbulent times. Youth voices are key for developing transformative solutions to the climate crisis, and working with youth needs to be done intentionally, ensuring that they have agency and power to address existential challenges facing society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth5030066/s1: File S1: Recommended practices for Youth–Adult Partnerships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F.; Methodology, E.F.; Software, L.B.; Formal analysis, L.B.; Writing—original draft, E.F. and L.B.; Writing—review & editing, E.F. and L.B.; Visualization, E.F., L.B. with acknowledgement of Caitlin Hastings’ graphic design; Supervision, E.F.; Project administration, E.F.; Funding acquisition, E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funding by a SSHRC Connections Grant #611-2021-0254.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Lakehead Research Ethics Board (#1469071) on 11 October 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 7 YF Principles. (n.d.). Youth friendly. Available online: https://www.youthfriendly.com/7-principles (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Aleks Mingsheng, L. (2022). Equals, relatives, and kin: Growing intergenerational solidarity between youth activists and their adult accomplices. Columbia University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/a283aec80ae9639cc8cd6de03f5538d8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y&casa_token=0fqFSzLfJ6wAAAAA:3ht63o0lzzENoK7YVyTqOgovPyM3ItNQJlOdQUg631pYfoXW9G-IHWp0T2vW8PDkvVR6qEJSd2rA (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of planners, 35(4), 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokiasamy, E., Krauss, S., Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Pereria, S., & Costa, A. (2023). Capacity building of adult allies in youth-adult partnerships to facilitate youth participation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augsberger, A., Collins, M. E., Gecker, W., & Dougher, M. (2018). Youth civic engagement: Do youth councils reduce or reinforce social inequality? Journal of Adolescent Research, 33(2), 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L., & Roy, S. (2023). Measurement development and validation to capture perceptions of younger people’s climate action: An opportunity for intergenerational collaboration and dialogue. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 22, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barg, H. (2022). Youth got the power: Building youth adult partnerships for climate action—Proquest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2662752461?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Bell, J. (n.d.). Understanding adultism. A key to developing positive youth-adult relationships. Available online: https://www.nuatc.org/articles/pdf/understanding_adultism.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Bettencourt, G. M. (2020). Embracing problems, processes, and contact zones: Using youth participatory action research to challenge adultism. Action Research, 18(2), 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., Warner, A., Mambro, G. D., & Bedeaux, C. (2013). “Du carré rouge aux casseroles”: A context for youth-adult partnership in the québec student movement. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 4(3.1), 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botchwey, N. D., Johnson, N., O’Connell, L. K., & Kim, A. J. (2019). Including youth in the ladder of citizen participation: Adding rungs of consent, advocacy, and incorporation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 85(3), 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B., & Germaine, C. (2022). Sustaining the old world, or imagining a new one? The transformative literacies of the climate strikes. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 38(1), 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys and Girls Club of America. (n.d.). 5 quick tips: Here’s how adult allies can support youth advocacy. Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Available online: https://www.bgca.org/news-stories/2024/January/how-adult-allies-can-support-youth-advocacy/ (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Busch, K. C., Ardoin, N., Gruehn, D., & Stevenson, K. (2019). Exploring a theoretical model of climate change action for youth. International Journal of Science Education, 41(17), 2389–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, H., & Dadvand, B. (2018). Re-conceptualising youth participation: A framework to inform action. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, K. L., & Turner, D. C. (2021). “Maybe you should try it this way instead”: Youth activism amid managerialist subterfuge. American Educational Research Journal, 58(2), 386–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Strike. (2019). A guide to adult allyship in youth-led movements. Available online: https://lutheransrestoringcreation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Adult-Ally-Toolkit-Google-Docs.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Elsen, F., & Ord, J. (2021). The role of adults in “youth led” climate groups: Enabling empowerment. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 641154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R., & Lund, D. (2013). Forging ethical adult-youth relationships within emancipatory activism. International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, 4(3.1), 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, E., Schwartzberg, P., & Berger, P. (2019). Canada, climate change and education: Opportunities for public and formal education. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337111645_Canada_Climate_Change_and_Education_Opportunities_for_Public_and_Formal_Education (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Galway, L. P., & Field, E. (2023). Climate emotions and anxiety among young people in Canada: A national survey and call to action. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 9(2023), 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, P. C., & Chen, C. (2015). “Frayed all over:” The causes and consequences of activist burnout among social justice education activists. Educational Studies, 51(5), 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R. K., Field, E., & Berger, P. (2022). Bringing climate injustices to the forefront: Learning from the youth climate justice movement. In Justice and equity in climate change education (pp. 41–70). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. F. (2020). A conceptual mapping of three anti-adultist approaches to youth work. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(10), 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. A. (1992). Children’s Participation, from Tokenism to Citizenship. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, T., Walker, C., Parsons, K., Arya, D., Bowman, B., Germaine, R. L., Langford, S., Peacock, S., & Thew, H. (2023). In it together! Cultivating space for intergenerational dialogue, empathy and hope in a climate of uncertainty. Children’s Geographies, 21(5), 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A. (2023). From disenfranchisement to hope through youth-adult participatory action research. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(5), 1813–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeunesse Acadienne. (2017). Par et pour les jeunes; une explication. [PDF]. Available online: https://fjcf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/PAR-et-POUR-Doc-Explicatif.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Karsgaard, C., Pillay, T., & Shultz, L. (2022). Facing colonial Canada through pedagogies of equity for First Nations: An advocacy education project. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 21(4), 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsgaard, C., & Shultz, L. (2022, November 22). Youth movements and climate change education for justice. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedias of Education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. M., & Gislason, M. K. (2022). Intergenerational approaches to climate change mitigation for environmental and mental health co-benefits. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 8, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S., & Trott, C. D. (2024). Intergenerational solidarities for climate healing: The case for critical methodologies and decolonial research practices. Children’s Geographies, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocque, E. (2023). Co-envisioning the social-ecological transition through youth eco-activists’ narratives: Toward a relational approach to ecological justice. Journal of Community Practice, 31(2), 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M., Lynch, A. J., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Balint, L., Basher, Z., Chan, I., Jaureguiberry, P., Mohamed, A., Mwampamba, T. H., Palomo, I., Pliscoff, P., Salimov, R. A., Samakov, A., Selomane, O., Shrestha, U. B., & Sidorovich, A. A. (2017). Early-career experts essential for planetary sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 29, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, A. L., & Literat, I. (2020). “We need you to listen to us”: Youth activist perspectives on intergenerational dynamics and adult solidarity in youth movements. International Journal of Communication, 14, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A. J., Kronlid, D., & McGarry, D. (2015). Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Current Opinion in Environment Sustainability, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2018). From reticence to resistance: Understanding educators’ engagement with indigenous environmental issues in Canada. Environmental Education Research, 25(1), 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D., & Beers, R. A. V. (2020). Unintentional consequences: Facing the risks of being a youth activist. In Education, 26(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2020). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajer, N., & Earnest, J. (2009). Youth empowerment for the most vulnerable: A model based on the pedagogy of freire and experiences in the field. Health Education, 109(5), 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, K. (2019). Learning from young people engaged in climate activism: The potential of collectivizing despair and hope. Young, 27(5), 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. A. (2010). Exploring capacities and skills to generate youth adult partnerships for community change: Three community case studies. Michigan State University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/a0deb989f8f9ce02d105b5118b5e168a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&casa_token=gYSWY2VCT_wAAAAA:g-6F2e-zNm55DKd3nE-PzPa2DhpbQ1cVIajLmUrlHZqG7_IKv16O1wlekd0KI8EBqs7sWfiRcpk- (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Richardson, W. (2024). Confronting education in a time of complexity, chaos, and collapse [Manifesto]. Available online: https://futureserious.school/manifestoedu/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Robinson & Parker. (2024). Practices for transitions in a time between worlds. Stanford social innovation review supplement. Available online: https://ssir.ebookhost.net/ssir/digital/96/ebook/1/index.php?e=96&user_id=241847&flash=0 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Schmitt-McQuitty, L. (2007). Encouraging positive youth development with youth leadership summits. Journal of Youth Development, 1(3), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw-Raudoy, K., & McGregor, C. (2013). Co-learning in youth-adult emancipatory partnerships: The way forward? International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, 4(3.1), 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S., & Andreotti, V. (2021). Global citizenship otherwise. In Conversations on global citizenship education (pp. 13–36). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Students Commission Canada. (2023). Adult allies in action. Available online: https://www.studentscommission.ca/assets/pdf/tools/en/public/Adults_Allies_in_Action.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Susskind, Y. (2010). An empowerment framework for understanding, planning, and evaluating youth-adult engagement in community activism. In Emancipatory practices: Adult/youth engagement for social and environmental justice (pp. 199–219). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thew, H., Middlemiss, L., & Paavola, J. (2022). “You need a month’s holiday just to get over it!” exploring young people’s lived experiences of the UN climate change negotiations. Sustainability, 14(7), 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment. (2023). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/treaty-bodies/crc/general-comments (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). Global climate litigation report: 2023 status review. Available online: www.unep.org/resources/report/global-climate-litigation-report-2023-status-review (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Watson, L. (2024). Definition of an ally. Available online: https://equitas.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/A-guide-on-practicing-Youth-Allyship-Booklet-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Weybright, E., Hrncirik, L., White, A., Cummins, M., Deen, M. K., & Calodich, S. (2016). “I felt really respected and I know she felt respected too”: Using youth-adult partnerships to promote positive youth development in 4-H youth. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 4(3), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YOUNGO. (2022). COP 27 Global youth statement: Declaration for climate justice. Available online: https://coy17eg.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/GYS-2022-V.-Z.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- YOUNGO. (2023). Global youth statement COP28 Dubai. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/64e71b1580e9dc25aacc828d/t/6556a53d18157b2d49e1ae91/1700177231473/Global+Youth+Statement+Condensed+Demands (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Youth4Climate. (2021). Driving ambition manifesto. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Youth4Climate-Manifesto.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Zeldin, S., Christens, B. D., & Powers, J. L. (2013). The psychology and practice of youth-adult partnership: Bridging generations for youth development and community change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(3), 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurba, M., Stucker, D., Mwaura, G., Burlando, C., Rastogi, A., Dhyani, S., & Koss, R. (2020). Intergenerational dialogue, collaboration, learning, and decision-making in global environmental governance: The case of the IUCN intergenerational partnership for sustainability. Sustainability, 12(2), 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).