Make a Move: A Multi-Method, Quasi-Experimental Study of a Program Targeting Psychosexual Health and Sexual/Dating Violence for Dutch Male Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Make a Move

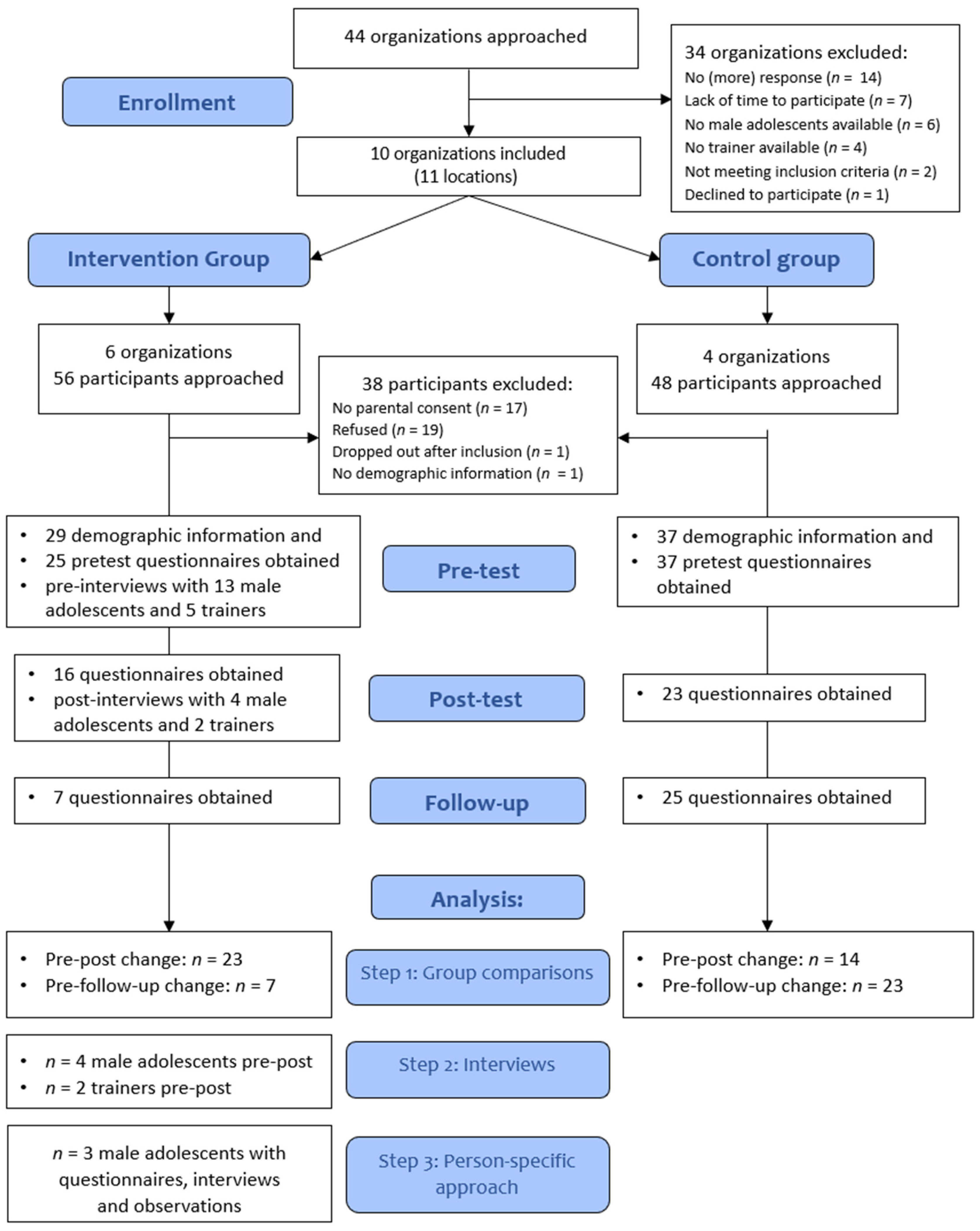

2.2. Design

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Recruitment

2.3.2. Consent and Ethical Standards

2.3.3. Data Collection

2.3.4. Compensation

2.4. Participants

2.4.1. Organizations

2.4.2. Total Male Adolescent Sample

2.4.3. Qualitative Subsample

2.5. Program Integrity Evaluation

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Questionnaires

2.6.2. Interviews

2.6.3. Observations

2.7. Analyses

2.7.1. Step 1: Quantitative Group Comparisons of Program Outcomes

2.7.2. Step 2: Perspectives of Program Trainers and Male Adolescents

2.7.3. Step 3: Multi-Method Case Descriptions

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Program Integrity

3.2.1. Adherence

3.2.2. Dosage

3.2.3. Quality of Delivery

3.2.4. Participant Responsivity

3.3. Effectiveness Step 1: Quantitative Group Comparisons on Program Outcomes

3.4. Effectiveness Step 2: Perspectives of Program Trainers and Male Adolescent Participants

3.4.1. Program Trainers

‘I think a lot can go wrong in communication. I think they really started to think about that, that you can’t just assume that someone wants to [have sex] or assume that someone doesn’t […] and that you’re like: Well, let’s go! You know? That they are much more aware of that. […] that it has planted a seed. That is the least, I hope, yes’.

‘Whether they will immediately act on it, that is often not the case. But it is clear to them. […] The information often reaches them, but directly acting on it is difficult. And I understand that. […] For some [I see behavioral changes] very clearly. And some just find that difficult’.

‘I always say: what you like, doesn’t have to be the same for another person. And having that conversation is very important, and don’t just do something. So, they know, but they also say that they find it difficult to interpret another person’s signals’.

3.4.2. Male Adolescents

‘Well first you would have to communicate with each other, what you like and don’t like. That is important for sure. And otherwise just prepare a bit. […] Mentally, of course, but also physically and then I mean, for example, have condoms or a pill for the woman. […] Just respect each other’s wishes and boundaries, as well. […] What do I like? What does she like? What can I do, what can I not do?’

3.5. Effectiveness Step 3: Multi-Method Case Descriptions

3.5.1. Sam’s Case Description

3.5.2. Marc’s Case Description

3.5.3. Alex’s Case Description

4. Discussion

4.1. Evidence for Program Effectiveness

4.1.1. Effects on (Inter)Personal Versus Sociocultural Factors

4.1.2. Effects on Behavior

4.2. Program Integrity

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ball, B., Holland, K. M., Marshall, K. J., Lippy, C., Jain, S., Souders, K., & Westby, R. P. (2015). Implementing a targeted teen dating abuse prevention program: Challenges and successes experienced by expect respect facilitators. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V., Edwards, K. M., Rizzo, A. J., Segura-Montagut, A., Greenberg, P., & Kearns, M. C. (2023). Mixed methods community-engaged evaluation: Integrating interventionist and action research frameworks to understand a community-building violence prevention program. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(4), 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K. C., Clayton, H. B., Rostad, W. L., & Leemis, R. W. (2020). Sexual violence victimization of youth and health risk behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(4), 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendixen, M., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2017). When less is more: Psychometric properties of Norwegian short-forms of the ambivalent sexism scales (ASI and AMI) and the Illinois rape myth acceptance (IRMA) scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(6), 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeije, H. R. (2014). Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen (2nd ed.). Boom onderwijs Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Bonevski, B., Randell, M., Paul, C., Chapman, K., Twyman, L., Bryant, J., Brozek, I., & Hughes, C. (2014). Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brush, L. D., & Miller, E. (2019). Trouble in paradigm: “Gender transformative” programming in violence prevention. Violence Against Women, 25(14), 1635–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Tena, L., Larmour, S. R., Pereda, N., & Eisner, M. P. (2024). Longitudinal associations between adolescent dating violence victimization and adverse outcomes: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 9). Preventing teen dating violence. In Injury prevention and control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/about-teen-dating-violence.html (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Clark, D. (2017). Boys will be boys: Assessing attitudes of athletic officials on sexism and violence against women. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 8(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condomines, B., & Hennequin, E. (2014). Studying sensitive issues: The contributions of a mixed approach. Revue Interdisciplinaire Sur Le Management Et l’Humanisme, 3(5), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, C. V., Jaffe, P., Dunlop, C., Kerry, A., & Exner-Cortens, D. (2019). Preventing gender-based violence among adolescents and young adults: Lessons from 25 years of program development and evaluation. Violence Against Women, 25(1), 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, A., Harries, T., Pizzirani, B., Hyder, S., Baldwin, R., Mayshak, R., Walker, A., Toumbourou, J. W., & Miller, P. (2023). Childhood predictors of adult intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization. Journal of Family Violence, 38(8), 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gee, F., Manuels, C., Boerwinkel, E. K., Yap, K., & Muntinga, M. E. (2022). ‘They say “I did it”, but they don’t say “I got an STI from it”’: Exploring the experiences of youth with a migration background with sexual health in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Global Public Health, 17(9), 2095–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, H., Oldenhof, A., Kraan, Y., Beek, T., Kuipers, L., & Vermey, K. (2024). Seks onder je 25e: Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2023 [Sex under the age of 25: Sexual health among young people in the Netherlands in 2023]. Eburon. Available online: https://rutgers.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Boek-S25-2023-incl-cover.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Holt, M. K., Massetti, G. M., Matjasko, J. L., & Tharp, A. T. (2014). A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Haas, S., van Berlo, W., Bakker, F., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2012). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence in the Netherlands, the risk of revictimization and pregnancy: Results from a national population survey. Violence & Victims, 27(4), 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deković, M., van Aken, M. A. G., Reitz, E., van de Bongardt, D., Baams, L., & Doornwaard, S. M. (2018). Project STARS (studies on trajectories of adolescent relationships and sexuality). Available online: https://ssh.datastations.nl/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.17026/dans-z6b-t8ft (accessed on 18 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- De Lijster, G., Felten, H., Kok, G., & Kocken, P. L. (2016). Effects of an interactive school-based program for preventing adolescent sexual harassment: A cluster-randomized controlled evaluation study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from randomized controlled trials to mixed methods intervention evaluations. In S. N. Hesse-Biber, & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp. 406–425). Oxford Library of Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S. L., & Barker, G. (2019). Gender-transformative approaches to engaging men in reducing gender-based violence: A response to Brush & Miller’s “Trouble in paradigm”. Violence Against Women, 25(14), 1657–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S. L., Fleming, P. J., & Colvin, C. J. (2015). The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(Suppl. 2), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerink, P. M., van den Eijnden, R. J., Ter Bogt, T. F., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2017). A scale for the assessment of sexual standards among youth: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellmeth, G., Heffernan, C., Nurse, J., Habibula, S., & Sethi, D. (2015). Educational and skills-based interventions to prevent relationship violence in young people. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(1), 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D., & Molina-Azorin, J. F. (2020). Utilizing a mixed methods approach for conducting interventional evaluations. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(2), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M. (2020). Engaging men and boys in violence prevention. Men, masculinities and intimate partner violence (pp. 155–169). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foshee, V. A., Benefield, T., Dixon, K. S., Chang, L., Senkomago, V., Ennett, S. T., Moracco, K. E., & Bowling, J. M. (2015). The effects of moms and teens for safe dates: A dating abuse prevention program for adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(5), 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, F., Özdemir, M., & Stattin, H. (2019). The implementation integrity of parenting programs: Which aspects are most important? Child & Youth Care Forum, 48, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L. M., Embry, V., Young, B. R., Macy, R. J., Moracco, K. E., Reyes, H. L. M., & Martin, S. L. (2021). Evaluations of prevention programs for sexual, dating, and intimate partner violence for boys and men: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 22(3), 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, K. P. (2014). A sex-positive framework for research on adolescent sexuality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2013). A secure base? the adolescent–staff relationship in secure residential youth care. Child & Family Social Work, 18(3), 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, S., & Weeland, J. (2019). Introduction to the special issue. randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in clinical and community settings: Challenges, alternatives, and supplementary designs. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2019(167), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., & Hoffman, M. E. (2018). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the method. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 846–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, C. A., Waterman, E. A., Edwards, K. M., Hopfauf, S. L., Simon, B. R., & Banyard, V. L. (2022). Attendance at a community-based, after school, youth-led sexual violence prevention initiative. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), NP23015–NP23034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime, M. C. D., McCauley, H. L., Tancredi, D. J., Nettiksimmons, J., Decker, M. R., Silverman, J. G., O’Connor, B., Stetkevich, N., & Miller, E. (2015). Athletic coaches as violence prevention advocates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(7), 1090–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP [computer software]. JASP Team. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker, M., De Haas, S., Kuyper, A., & Ohlrichs, Y. (2020). Handleiding make a move [Make a move manual]. Rutgers. [Google Scholar]

- Lemire, C., Rousseau, M., & Dionne, C. (2023). A comparison of fidelity implementation frameworks used in the field of early intervention. American Journal of Evaluation, 44(2), 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndon, A. E., Duffy, D. M., Smith, P. H., & White, J. W. (2011). The role of high school coaches in helping prevent adolescent sexual aggression: Part of the solution or part of the problem? Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(4), 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E., Jones, K. A., Culyba, A. J., Paglisotti, T., Dwarakanath, N., Massof, M., Feinstein, Z., Ports, K. A., Espelage, D., Pulerwitz, J., Garg, A., Kato-Wallace, J., & Abebe, K. Z. (2020). Effect of a community-based gender norms program on sexual violence perpetration by adolescent boys and young men A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 3(12), e2028499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E., Tancredi, D. J., McCauley, H. L., Decker, M. R., Virata, M. C., Anderson, H. A., Stetkevich, N., Brown, E. W., Moideen, F., & Silverman, J. G. (2012). “Coaching boys into men”: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 51(5), 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. A., Smith, E. A., Caldwell, L. L., Mathews, C., & Wegner, L. (2021). Boys are victims, too: The influence of perpetrators’ age and gender in sexual coercion against boys. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP3409–NP3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miočević, M., Levy, R., & Savord, A. (2020). The role of exchangeability in sequential updating of findings from small studies and the challenges of identifying exchangeable data sets. In Small sample size solutions (pp. 13–29). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, X. (2021). Easy language in The Netherlands. Handbook of Easy Languages in Europe, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchowski, L. M. (2019). “Trouble in paradigm” and the social norms approach to violence prevention. Violence Against Women, 25(14), 1672–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedneault, C. I., Nunes, K. L., Hermann, C. A., & White, K. (2022). Evaluative attitudes may explain the link between injunctive norms and sexual aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3–4), 1933–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E. L., Byers, E. S., Belliveau, N., Bonner, R., Caron, B., Doiron, D., Greenough, J., Guerette-Breau, A., Hicks, L., & Landry, A. (1999). The attitudes towards dating violence scales: Development and initial validation. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, D. E., Early, M. S., & Holland, K. M. (2017). Boys are victims too? sexual dating violence and injury among high-risk youth. Preventive Medicine, 101, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, C., Eads, M., & Barker, G. (2011). Engaging boys and young men in the prevention of sexual violence. SVRI. Available online: https://www.svri.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2016-04-12/menandboys.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ricardo, C., & Verani, F. (2010). Engaging men and boys in gender equality and health: A global toolkit for action. Available online: https://www.ungei.org/publication/engaging-men-and-boys-gender-equality-and-health (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ridderinkhof, A., Elmose, M., de Bruin, E. I., Blom, R., Salem-Guirgis, S., Weiss, J. A., van der Meer, P., Singh, N. N., & Bögels, S. M. (2021). A person-centered approach in investigating a mindfulness-based program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Mindfulness, 12(10), 2394–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, D., Moore, S., & Flynn, I. (1991). Adolescent self-efficacy, self-esteem and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 1(2), 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane-McAteer, E., Gillespie, K., Amin, A., Aventin, Á., Robinson, M., Hanratty, J., Khosla, R., & Lohan, M. (2020). Gender-transformative programming with men and boys to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights: A systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ Global Health, 5(10), e002997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santor, D. A., Messervey, D., & Kusumakar, V. (2000). Measuring peer pressure, popularity, and conformity in adolescent boys and girls: Predicting school performance, sexual attitudes, and substance abuse. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalet, A. T., Santelli, J. S., Russell, S. T., Halpern, C. T., Miller, S. A., Pickering, S. S., Goldberg, S. K., & Hoenig, J. M. (2014). Invited commentary: Broadening the evidence for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and education in the United States. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2023). ATLAS.ti Scientific software development GmbH [computer software]. Scientific Software Development GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2020, December 18). Religieuze betrokkenheid naar achtergrondkenmerken. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2020/religie-in-nederland/3-religieuze-betrokkenheid-naar-achtergrondkenmerken (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Tharp, A. T., DeGue, S., Valle, L. A., Brookmeyer, K. A., Massetti, G. M., & Matjasko, J. L. (2013). A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 14(2), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2021). Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: A systematic review of studies since 2010. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021(178), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, S., Pleysier, S., & Walrave, M. (2023). Non-consensual dissemination of sexual images: The victim-offender overlap. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Schoot, R., Kaplan, D., Denissen, J., Asendorpf, J. B., Neyer, F. J., & Van Aken, M. A. (2014). A gentle introduction to Bayesian analysis: Applications to developmental research. Child Development, 85(3), 842–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J., Van den Bergh, D., Böhm, U., Dablander, F., Derks, K., Draws, T., Etz, A., Evans, N. J., Gronau, Q. F., & Haaf, J. M. (2021). The JASP guidelines for conducting and reporting a Bayesian analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erve, N., Poiesz, M., & Veerman, J. W. (2007). Treatment in child and youth care: Manual B-test. nijmegen, the netherlands: Praktikon. Kind en Adolescent, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lieshout, S., Mevissen, F. A., & Ruiter, R. A. (2014). Make a move and long live love+: Implementation and evaluation of two dutch sex education programs (pp. 46–68). Chapter 3. Maastricht University. ISBN 978-94-92597-03-8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout, S., Mevissen, F. E., van Breukelen, G., Jonker, M., & Ruiter, R. A. (2019). Make a move: A comprehensive effect evaluation of a sexual harassment prevention program in Dutch residential youth care. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(9), 1772–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Widenfelt, B. M., Goedhart, A. W., Treffers, P. D., & Goodman, R. (2003). Dutch version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M. C., Luijk, M., Weeland, J., & Van de Bongardt, D. (2021). Pre-registration: Move up! two mixed-methods cluster RCTs of programs targeting psycho-sexual health and sexual- and dating violence of male youth in vocational education, or with mild intellectual disabilities. Available online: https://osf.io/jfmau (accessed on 14 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M. C., Van de Bongardt, D., Luijk, M., & Weeland, J. (2023a). Pre-registration: Effectiveness of a psychosexual health promotion and sexual violence prevention program for Dutch male adolescents. Available online: https://osf.io/9vdqf (accessed on 14 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M. C., Van de Bongardt, D., Luijk, P. C. M., Miller, E., Slob, E., & Weeland, J. (2025). Make a Move+: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a program targeting psychosexual health and sexual and dating violence for Dutch male youth with mild intellectual disabilities. Youth. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, M. C., Weeland, J., Luijk, M., & van de Bongardt, D. (2023b). Sexual and dating violence prevention programs for male youth: A systematic review of program characteristics, intended psychosexual outcomes, and effectiveness. Archives of Sexual Behavior, Open Access, 52(7), 2899–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugteveen, J., de Bildt, A., & Timmerman, M. E. (2022). Normative data for the self-reported and parent-reported strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) for ages 12–17. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhout, J., Posthumus, H., Joosten, M., & Zweerink, J. (2022). Richting een nieuw verdeelmodel voor lwoo [Towards a new distribution model for special education]. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/rapportages/2022/richting-een-nieuw-verdeelmodel-voor-lwoo/3-leerlingkenmerken (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Wincentak, K., Connolly, J., & Card, N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M. L., & Thompson, R. E. (2018). Predicting the emergence of sexual violence in adolescence. Prevention Science, 19(4), 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Characteristics | Total N = 66 | Intervention n = 29 | Control n = 37 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 16.59 (2.42) | 14.52 (1.15) | 18.14 (1.84) |

| % Total | % Intervention | % Control | |

| Ethnocultural identity a | |||

| Fully Dutch | 69.1 | 62.1 | 72.2 |

| Surinamese(-Dutch) | 7.3 | 13.8 | 2.9 |

| Turkish(-Dutch) | 1.5 | 0 | 2.8 |

| Asian(-Dutch) | 5.8 | 6.9 | 5.6 |

| Mixed ethnicity, non-Dutch | 1.5 | 0 | 2.8 |

| Other European(-Dutch) | 7.4 | 10.3 | 5.6 |

| Moroccan(-Dutch) | 4.4 | 6.8 | 2.8 |

| African(-Dutch) | 2.9 | 0 | 5.6 |

| Religious | 22.9 | 20.7 | 21.6 |

| Daily occupation | |||

| School | 89.5 | 95.5 | 87.1 |

| Work | 10.5 | 4.5 | 12.9 |

| Level of education | |||

| Elementary School | 1.6 | 3.6 | 0 |

| Special Secondary Education | 9.4 | 0 | 15.6 |

| Secondary Education | 53.1 | 70.8 | 37.5 |

| Vocational Secondary School | 25.0 | 3.6 | 43.8 |

| Unknown/no education | 10.9 | 21.4 | 3.1 |

| Living situation | |||

| With both parents | 45.7 | 31.0 | 56.8 |

| With one parent | 30.0 | 37.9 | 24.3 |

| In youth care | 8.6 | 17.2 | 2.7 |

| With one parent and stepparent | 5.7 | 6.9 | 8.1 |

| Other (e.g., foster, brother, alone) | 5.7 | 3.4 | 8.1 |

| Switching between divorced parents | 2.9 | 6.9 | 0 |

| Romantic relationship experience | 84.1 | 89.7 | 81.1 |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 92.8 | 86.2 | 97.3 |

| Bisexual | 2.8 | 6.8 | 0 |

| Homosexual | 1.4 | 3.4 | 0 |

| Not sure yet/would rather not say | 2.8 | 3.4 | 2.7 |

| Any interpersonal sexual experience | 65.2 | 58.6 | 73.0 |

| Of non-experienced: Intention to have sex next year | |||

| Yes (probably) | 26.7 | 18.8 | 35.7 |

| Maybe, maybe not | 33.3 | 25.0 | 42.9 |

| No (probably not) | 40.0 | 56.2 | 21.4 |

| Concept | Instrument | Number of Items | Example Item | Answer Options | Scale Score | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | ||||||

| Adversarial Sexual Beliefs | Burt (1980), adapted by Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 3 | I think women mostly date men to make use of them | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.61 |

| Attitudes Toward Dating Violence | Attitudes toward male dating violence (AMDV) scale (Price et al., 1999) used in Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 8 | Some girls/boys deserve to be slapped by their boyfriends | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.73 |

| Attitudes Toward Positive Sexual Behavior | Perceived Sexual Competence Scale (Deković et al., 2018) | 5 | When I have sex … (Adapted from ‘I [do] …’ to) I think it is important to … pay a lot of attention to what the person whom I have sex with likes | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.86 |

| Attitudes Toward Sexual Communication | Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 3 | Asking my girlfriend/boyfriend what they do and do not want during sex, seems to me … Good/Important/Comfortable | [item 1]; 1 = Not good at all—5 = Very good | Mean | 0.91 |

| Heterosexual Double Standards | Scale for the Assessment of Sexual Standards Among Youth (SASSY; Emmerink et al., 2017) | 6 | I think that a girl who takes the initiative in sex is pushy | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.82 |

| Rape Myth Acceptance | Items from Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale Short Form (IRMA-SF; Bendixen & Kennair, 2017) | 4 | Rephrased into short vignettes: A girl got drunk at a party. Someone fingered her while she did not want to. A friend of yours says ‘If she was that drunk | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.76 |

| Attitudes | ||||||

| Rape Myth Acceptance | Items from Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale Short Form (IRMA-SF; Bendixen & Kennair, 2017) | 4 | it’s kind of her own fault something like that happened’, to what extent do you agree with this friend? | 1 = Strongly disagree—5 = Strongly agree | Mean | 0.76 |

| Attitudes and Cognitions about Love, Intimacy and Sexuality | Interview Questions | Youth:

| ||||

| Social norms | ||||||

| Injunctive Norms | Self-constructed, based on previous work (e.g., see Pedneault et al., 2022) | 2 | You kiss a person you like, even though this person did not want to. How acceptable do your (1) friends; (2) parents think this is? | 1 = Not at all acceptable—5 = Very acceptable | Mean | 0.80 |

| Perception of Normalcy of SDV | Perceived Social Norms Scale (De Lijster et al., 2016), rephrased | 5 | A friend of yours randomly pinches someone’s butt. How normal do you consider this behavior to be? | 1 = Not normal at all—5 = Very normal. | Mean | 0.59 |

| Skills | ||||||

| Resilience to Peer Pressure | Peer Pressure Scale (Santor et al., 2000) translated and item added by Deković et al. (2018) | 6 | I’ve done dangerous or foolish things because others dared me to | 1 = Never—6 = Very often | Mean | 0.57 |

| Romantic and Sexual Interaction Competency | Interview questions | Adolescents:

| ||||

| Self-efficacy | ||||||

| Self-efficacy to ‘say no’ | ‘Say No’ subscale from the Sexual Self Efficacy Scale (SSE; Rosenthal et al., 1991) | 5 | Rephrased into short vignettes: You’ve been with you partner for a while. You’ve kissed before, but you haven’t engaged in anything sexual yet. One night you’re lying on the bed. Suddenly they push your hand into their pants. You don’t feel comfortable with this yet. How good are you at indicating that you don’t want to do this yet? | 1 = Not good at all—5 = Very good | Mean | 0.80 |

| Self-efficacy for Self-Regulation | Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 4 | I am able not to get angry when my partner isn’t in the mood for sex | 1 = Not at all—5 = Completely | Mean | 0.92 |

| Self-efficacy for Sexual Communication | Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 5 | I am able to talk to the person I’m having sex with about what I do and don’t want | 1 = Not at all—5 = Completely | Mean | 0.91 |

| Intentions | Vignette: Imagine you are in a relationship. You are in bed together, talking. You are starting to feel like you want to have sex, but the other person does not want to. What do you do? | |||||

| Positive | One item from Van Lieshout et al. (2019), two self-constructed | 3 | When I want to have sex, but the other person does not, I will: Example item: Leave them alone | 1 block = Very unlikely to react like this—7 blocks = Certain to react like this | Mean | 0.67 |

| Negative | Van Lieshout et al. (2019) | 3 | When I want to have sex, but the other person does not, I will: Example item: Get angry | 1 block = Very unlikely to react like this—7 blocks = Certain to react like this | Mean | 0.76 |

| SDV Perpetration | Sexual Abuse Subscale 5 items, Foshee et al. (2015); one item from De Haas et al. (2012); one item self-constructed | 7 | How often have you sent or shown a naked picture of someone else to others? At post-test & follow-up: Since the last measurement | 0 = Never, 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3 or 4 times, 3 = More than 4 times. | Sum (0–7) & Dichotomous (0 = No experience, 1 = At least one experience) | NA |

| Behavioral Change | Interview questions: | Adolescents:

| ||||

| General Estimates of Program Effectiveness by Participants | Interviews questions: | Adolescents

| ||||

| Pre-Test M (SD) | Post-Test M (SD) | Follow-Up M (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Attitudes | n = 27 | n = 35 a | n = 16 b | n = 23 | n = 7 | n = 24 c |

| Adversarial sexual beliefs | 2.33 (0.82) | 2.56 (0.68) | 2.78 (1.19) | 2.59 (1.02) | 3.33 (1.20) | 2.51 (0.86) |

| Attitudes toward communication | 4.15 (1.00) | 3.99 (1.06) | 4.15 (0.88) | 3.90 (0.94) | 4.14 (0.63) | 4.03 (1.11) |

| Attitudes toward dating violence | 2.07 (0.59) | 1.83 (0.49) | 2.38 (0.74) | 2.06 (0.67) | 2.86 (0.84) | 2.18 (0.88) |

| Attitudes toward positive sexual behavior | 3.94 (1.10) | 3.87 (0.92) | 4.41 (0.65) | 3.86 (0.94) | 3.80 (1.20) | 3.99 (0.88) |

| Heterosexual double standards | 1.93 (0.69) | 2.05 (0.77) | 2.09 (0.96) | 2.09 (0.91) | 2.38 (0.95) | 2.13 (0.74) |

| Rape myth acceptance | 2.36 (0.99) | 2.07 (0.77) | 2.16 (0.58) | 2.13 (0.72) | 2.75 (0.79) | 1.89 (0.80) |

| Social Norms | n = 27 | n = 31 | n = 16 | n = 23 | n = 7 | n = 24 |

| Injunctive norms | 1.85 (0.86) | 2.15 (1.29) | 1.63 (0.70) | 1.67 (0.86) | 1.71 (0.39) | 1.63 (0.73) |

| Perceiving SDV as normal | 1.81 (0.72) | 1.73 (0.47) | 1.74 (0.53) | 1.83 (0.72) | 1.94 (0.57) | 1.53 (0.49) |

| Skills | n = 27 | n = 35 | n = 16 | n = 23 | n = 7 | n = 24 |

| Resilience to peer pressure | 5.11 (0.56) | 5.26 (0.52) | 5.31 (0.49) | 5.01 (0.72) | 5.45 (0.49) | 5.43 (0.51) |

| Self-efficacy | n = 27 | n = 31 | n = 16 | n = 23 | n = 7 | n = 24 d |

| Say no | 3.84 (0.80) | 3.87 (0.94) | 4.00 (0.69) | 3.85 (0.69) | 4.17 (0.48) | 3.51 (1.21) |

| Self-regulation | 4.28 (1.05) | 4.02 (1.00) | 4.38 (0.72) | 4.14 (0.99) | 4.11 (0.72) | 4.03 (1.01) |

| Sexual communication | 4.17 (1.00) | 3.76 (1.13) | 4.13 (0.65) | 3.78 (1.01) | 4.25 (0.51) | 3.77 (1.07) |

| Intentions | n = 27 | n = 35 | n = 16 | n = 23 | n = 7 | n = 24 |

| Positive intentions | 5.78 (1.38) | 4.77 (1.36) ** | 5.48 (1.33) | 5.22 (1.39) | 4.10 (1.72) | 4.51 (1.65) |

| Negative intentions | 1.51 (0.91) | 1.82 (1.14) | 1.46 (0.83) | 1.88 (0.99) | 1.71 (0.80) | 1.65 (1.10) |

| Pre-Test (%) | Post-Test (%) | Follow-Up (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 27) | Control (n = 34) | Intervention (n = 16) | Control (n = 23) | Intervention (n = 7) | Control (n = 24) | |

| Coercion into sexual acts | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Forwarding or showing others’ nude/sexy photos without consent | 22.2 | 11.8 | 25 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 |

| Kissing without consent | 18.5 | 8.6 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 8.3 |

| Persuading into sexual acts | 7.4 | 8.8 | 12.5 | 8.7 | 28.6 | 8.3 |

| Showing genitals without consent | 0.0 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Showing pictures/videos of naked people without consent | 14.8 | 34.3 | 18.8 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.2 |

| Touching private parts without consent | 3.7 | 2.9 | 12.5 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Range in sum of experiences | 0–4 | 0–3 | 0–6 | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0–1 |

| Any SDV in % | 37.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 13.0 | 28.6 | 20.8 |

| Outcome | Baseline—Post-Test | Baseline—Follow-Up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior M (SD) | BF10 | Posterior δ | 95% CI | Prior M (SD) | BF10 | Posterior δ | 95% CI | |

| Adversarial sexual beliefs | −0.324 (0.672) | 0.519 | 0.212 | −0.376, 0.820 | −0.377 (0.588) | 1.442 | 0.525 | −0.181, 1.232 |

| Attitudes toward communication | 0.411 (0.661) | 0.377 | −0.010 | −0.602, 0.581 | 0.361 (0.612) | 0.487 | 0.033 | −0.659, 0.725 |

| Attitudes toward dating violence | 0.042 (0.507) | 0.558 | 0.035 | −0.517, 0.588 | −0.436 (0.409) | 0.664 | −0.291 | −0.873, 0.292 |

| Attitudes toward positive behavior | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 0.598 | 0.325 | −0.256, 0.961 | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 0.443 | −0.176 | −0.927, 0.514 |

| Heterosexual double standards | −0.115 (0.589) | 0.502 | −0.039 | −0.625, 0.547 | −0.401 (0.499) | 0.480 | −0.046 | −0.688, 0.597 |

| Rape myth acceptance | −0.249 (0.607) | 2.004 | −0.528 | −1.136, 0.079 | −0.064 (0.445) | 0.786 | 0.150 | −0.470, 0.769 |

| Injunctive social norms | 0.176 (1.114) | 0.323 | 0.135 | −0.523, 0.794 | 0.324 (1.036) | 0.691 | 0.452 | −0.353, 1.257 |

| Perception of normalcy of DV | 0.176 (1.114) | 0.308 | −0.087 | −0.746, 0.571 | 0.324 (1.036) | 0.491 | 0.299 | −0.501, 1.099 |

| Resilience to peer pressure | 0.333 (0.771) | 5.367 | 0.738 | 0.110, 1.367 | 0.328 (0.837) | 0.923 | 0.480 | −0.280, 1.239 |

| Self-efficacy to ‘say no’ | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 0.346 | −0.074 | −0.686, 0.520 | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 0.849 | 0.459 | −0.273, 1.319 |

| Self-efficacy for self-regulation | 0.019 (0.760) | 0.487 | −0.173 | −0.801, 0.455 | −0.446 (0.721) | 0.455 | 0.117 | −0.624, 0.859 |

| Self-efficacy for sexual communication | 0.487 (0.572) | 0.368 | −0.030 | −0.619, 0.559 | 0.352 (0.609) | 0.776 | 0.338 | −0.336, 1.042 |

| Positive intentions | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 0.421 | −0.211 | −0.810, 0.351 | NI Cauchy (0.707) | 1.070 | −0.489 | −1.209, 0.151 |

| Negative intentions | 0.011 (0.870) | 0.364 | 0.016 | −0.603, 0.636 | 0.285 (0.946) | 0.403 | −0.070 | −0.841, 0.700 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verbeek, M.C.; van de Bongardt, D.; Luijk, M.P.C.M.; Weeland, J. Make a Move: A Multi-Method, Quasi-Experimental Study of a Program Targeting Psychosexual Health and Sexual/Dating Violence for Dutch Male Adolescents. Youth 2025, 5, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020041

Verbeek MC, van de Bongardt D, Luijk MPCM, Weeland J. Make a Move: A Multi-Method, Quasi-Experimental Study of a Program Targeting Psychosexual Health and Sexual/Dating Violence for Dutch Male Adolescents. Youth. 2025; 5(2):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020041

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerbeek, Mirthe C., Daphne van de Bongardt, Maartje P. C. M. Luijk, and Joyce Weeland. 2025. "Make a Move: A Multi-Method, Quasi-Experimental Study of a Program Targeting Psychosexual Health and Sexual/Dating Violence for Dutch Male Adolescents" Youth 5, no. 2: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020041

APA StyleVerbeek, M. C., van de Bongardt, D., Luijk, M. P. C. M., & Weeland, J. (2025). Make a Move: A Multi-Method, Quasi-Experimental Study of a Program Targeting Psychosexual Health and Sexual/Dating Violence for Dutch Male Adolescents. Youth, 5(2), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020041