Christian Youth Adventure Camps: Evidencing the Potential for Values-Based Education to THRIVE

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Educational Philosophies Underpinning YACs

1.2. Values-Based Education in School Camps

1.3. Intentional Pedagogies

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design

Demographic: Can you tell us a little bit about your background? So, what you’ve done prior to here, how you got involved with CYAC?Induction: Can you tell me about your induction and training when you first came to work at CYAC?Purpose of Camp: What do you think the purpose of CYAC is? What is important about outdoor adventure camps?Effectiveness: What do you do to help achieve the purpose of the camp? What things do you think indicate that you have been successful as a camp leader?

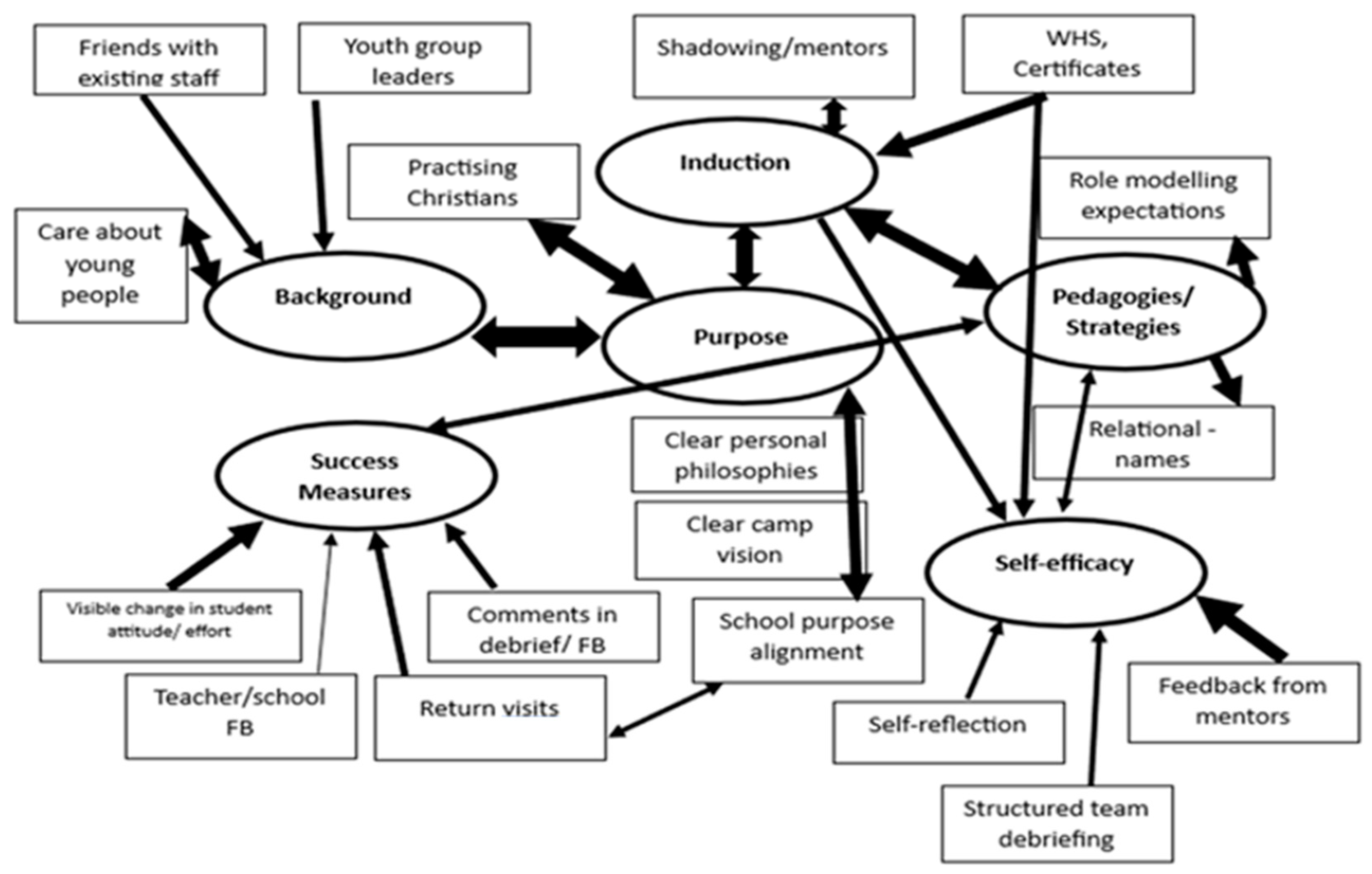

3. Results

3.1. Goal Setting

[I] always set goals...and if we have that outcome in mind, the process towards that outcome will be so much better, rather than just doing it for the sake of doing it.

rather than just going on the night beach walk, see it as an opportunity to actually chat to people you don’t usually chat to at school.

3.2. Effective Communication

Camp leader: Before I tell you guys the plan for the evening, and before we head back to camp, we are going to have something that CYAC likes to call a debrief or reflection, so we can look back on our activity and maybe think of some highlights and what we think we can learn from it. Before we get started, can anyone remember our three goals for camp?Student: Having fun!Camp Leader: Yes,Student: Teamwork!Camp Leader: Yes, and what was the last one?Student: Friendship!Camp Leader: yes, beautiful. Everyone says, “You are my friend”.All students: You are my friend!Camp leader: So, those are our big three values we are focusing on overall for camp. Friendship, teamwork, and having fun. It might be difficult to focus on friendship when we are doing an individual sport like surfing, but hopefully, you had fun surfing with, and crashing into, your friends! One of the other things we really focus on when we do surfing is resilience. So, I want to hear from you guys about some instances when maybe you were hit by a board, or run over by a board. Throw it out there!Student: I got smashed in the jaw by a board.Camp leader: Alright. Who thinks they can top getting an uppercut by a board?[Four more examples were provided by the students of being hit with a board or injured]Camp leader: So, nearly everyone had an experience of being hit by a board. But, friends, take a look around, we are all still sitting here, we are all still alive, we are having a little giggle, and everything is fine. So, now, we are going to go around the circle, and I want to hear a funny/favorite moment from all of you.

We’ll be walking through the national park, and one of the kids will be like, “Oh, man, this sucks.” We’re like, “No, resilience.” It might be a bit of a joke, but at least something’s going on, and it’s like they’re reciprocating that kind of language.(CYAC leader)

3.3. Modelling

for me... it’s leading. My role is to lead by example in front of the kids. Another camp leader noted thatfor me, the biggest one would be to lead by example. I think I always touch base with my groups on what it means to be a leader. To me, a leader is someone who does what they want the kids to do before the kids do it so they are in front of them, leading them through the steps.

3.4. Challenging

There are so many different activities. You can get to problem solving initiative games, which are completely different to doing something like surfing. They just involve different people in a lot of different ways, and they get the opportunity to share their strengths.

We do a lot of activities that you couldn’t make it through yourself. There was this mini wall, and you had to get over it, but you couldn’t get over it unless you helped push one person up. [This involved] relationship skills and teamwork, responsibility, independence, perseverance, emotion regulation, and self-confidence.

3.5. Building Relationships

3.6. Promoting Values

4. Conclusions

5. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, B. G., & Crafford, A. (2012). Identity at work: Exploring strategies for identity work. Journal of Industrial Psychology, 38(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinegar, K. M., Moulton, M., Falbe, K. N., Rintamaa, M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2024). Navigating opportunities for middle level education research: The MLER SIG research agenda. RMLE Online, 47(8), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, T. (2021). Husserl’s theory of signitive and empty intentions in logical investigations and its revisions: Meaning intentions and perceptions. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 52(1), 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, P. (2014). Fact, value and philosophy education. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 1(1), 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carspecken, P. F. (1996). Dialogical data generation through interviews, group discussions and IPR. In Critical ethnography in educational research: A theoretical and practical guide (pp. 154–163). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Training, Queensland [DET QLD]. (2023). Curriculum activity risk assessment guidelines. Available online: https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/stages-of-schooling/CARA/activity-guidelines (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Department of Education and Training, Victoria [DET VIC]. (2020). High impact teaching strategies: Excellence in learning and teaching. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/support/high-impact-teaching-strategies.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Department of Education and Training, Victoria [DET VIC]. (2023). Adventure activities specific activity guidelines. Available online: https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/excursions/guidance/adventure-activities#adventureactivity-guidelines (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Dewey, J. (Ed.). (1916). The existence of the world as a logical problem. In Essays in experimental logic (pp. 281–302). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, B., & Casey, A. (2016). Cooperative learning in physical education and physical activity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Furco, A. (2023). Service-learning as values education. In Springer international handbooks of education (Vol. Part F1708, pp. 427–448). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garst, B. A., Browne, L. P., & Bialeschki, M. D. (2011). Youth development and the camp experience. New Directions for Youth Development, 2011, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E. C. (2024). Impact of values education in daily lives of students: A qualitative study. Southeast Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 4(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, K. (1964). The outward bound way: How to use adventure to build resilience, leadership, and teamwork. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, L. M., & Bishop, P. A. (2021). The evolving middle school concept: This we (still) believe. Current Issues in Middle Level Education, 25(2), 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximising impact on learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R. (2002). The crux of risk management in outdoor programs—Minimising the possibility of death and disabling injury. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 6(2), 71. Available online: https://www.outdoorsvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/TheCruxofRiskManagement_Hogan_AJOE_2002.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Layder, D. (2004). Social and personal identity: Understanding yourself. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Main, K., & Whatman, S. (2023). Pedagogical Approaches of a Targeted Social and Emotional Skilling Program to Re-Engage Young Adolescents in Schooling. Education Sciences, 13(6), 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J. (2021). The impact of outdoor education on executive function in adolescents. University of Lethbridge (Canada). [Google Scholar]

- Orson, C. N., McGovern, G., & Larson, R. W. (2020). How challenges and peers contribute to social-emotional learning in outdoor adventure education programs. Journal of Adolescence, 81, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarelli, A., Hall, E., & Anderson, M. (2010). A strengths-based approach to outdoor and adventure education: Possibilities for personal growth. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(2), 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C. S. (1903). Pragmatism as a principle and method of right thinking: The 1903 Harvard lectures on pragmatism. State University of New York Press, Albany. [Google Scholar]

- Quay, J. (2016). Outdoor education and school curriculum distinctiveness: More than content, more than process. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, J., & Seaman, J. (2013). John Dewey and education outdoors: Making sense of the ‘educational situation’ through more than a century of progressive reforms. Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, D., Sibthorp, J., & Wilson, C. (2019). Understanding the role of summer camps in the learning landscape: An exploratory sequential study. Journal of Youth Development, 14(3), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohnke, K. E. (2000). Kurt Hahn address–2000 AEE international conference. Journal of Experiential Education, 23(3), 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, J. (2019). Restoring culture and history in outdoor education research: Dewey’s theory of experience as a methodology. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 11(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, J. (2018). The fundamental characteristics and unique outcomes of Christian summer camp experiences. Journal of Youth Development, 13(1–2), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, S., Widmer, M., Duerden, M., & Draper, C. (2009). The attributes of effective field staff in wilderness programs: Changing youths’ perspectives of being “cool”. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 43(1), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, C. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD). [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J. (2024). A measure of psychological anti-fragility: Development and replication. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, R., Taylor, N., & Gard, M. (2023). Environmental attunement continued: People, place, land and water in health education, sport and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 28(6), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C., & Sibthorp, J. (2018). Examining the role of summer camps in developing academic and workplace readiness. Journal of Youth Development, 13(1–2), 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, K. (2022). Experiential learning from the perspective of outdoor education leaders. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism, 30, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview Data | Initial Codes | Eventual Theme |

|---|---|---|

| “I’ve been with CYAC for a year and a half now. I started last year, about February. Beforehand I was doing chaplaincy and residential youth care. I did those for about a year, together. Then that’s when [colleague], who works here, she actually recommended me to try to get a job here. So, I left it for about six months, and then the beginning of last year is when I tried to step in, and then sort of welcomed me with open arms, which is cool. So, I’ve been full-time here since I started.” | Care about young people | Background |

| “I ended up going in back to studying and studied my diploma of ministry, Christian Ministry, for a year. That was last year. And then just sort of made the call that it was time to go back to some full-time work and volunteer at Red Frog’s during Schoolies *. And so, one of the managers here, she was actually the domain coordinator at Red Frogs, she was one of my leaders and just got talking with her about it and she was like, “Yeah, you should come in and have a look, see if you like it.” [* Schoolies is a week-long end of year celebration for Year 12 students and, as they are often under 18 years of age, community organisations volunteer to keep watch over them in public spaces and give out red frog lollies]. | Care about young people | Background |

| Notes | Coding |

|---|---|

| “Hello [school name]. My name is [name]. Who’s excited for camp? Who has been to [camp] before? Look at the window behind you, can you see the national park? This camp has been here for 87 years.” | General motivational, engagement strategy |

| The leader outlines the program for the day. First, the students will watch the safety induction video, then have some morning tea, then get into groups for cabins. “Thumbs up if you understand? Double thumbs up if you are super excited for camp?” Students are asked to take a toilet break; refill water bottles then return to the room. Some students stay, most take the opportunity. | Signposting what will unfold for students which both motivates and assures students. Prioritising safety |

| First activity after morning tea in courtyard. “We have a saying at camp—if it is to be, it is up to me. This can mean lots of things. One way it can be is getting ready. It is a personal responsibility. Being on time for activities is on you. Remembering your hat, water bottle, dry shoes, wet shoes etc. is on you. Another way this could play out is when someone might do something that upsets you. It’s up to you how you respond to that. Another way concerns safety. Parents rely on us to keep you safe. But if you’re not doing the right thing, it’s harder for us to keep you safe”. Leader explains that there is an important surf safety video to watch. Plays video, steps just outside but within view of the room to speak to teachers. | Contextualising the THRIVE philosophy for the age group Meeting OECA competencies: safety |

| Observation | Intentional Pedagogy/Example | Alignment with THRIVE Philosophy |

|---|---|---|

| Throughout Camp | Carrying equipment and/or food for each other between locations. Being generous with their time and support for each other as they helped and encouraged one another during activities. | Generosity |

| Day 1 Communal eating & Debrief | Christian schools may say Grace before eating. Leaders may ask, “tell me something you learned today about you, a friend, or God?” Raising students’ awareness of the beauties of the area and God’s creations; recognising themselves as children of God; being reminded that God loves them and has a purpose for them. | Spirituality |

| Day 1 setting expectations | Leader asks, “Have you tried giant paddle boarding before? Or tubing?”. “Why do you think it is important to try new things?”. Leader asks, “Think about the rewarding feeling, how proud you are of yourself when you push yourself outside of your comfort zone”. | Antifragility |

| Day 2 activity debrief | After activity session, during afternoon tea. Before receiving the afternoon tea snack, Leader asks, “Tell us one thing you are grateful for?”. A variation of this is, “What was something that one of your classmates did today that you appreciate them for?” | Gratitude |

| Day 1 setting expectations for camp All camp | Leaders use warm up games to learn everyone’s name quickly and consistently use students’ names. Leaders consistently and deliberately use students’ names; take opportunities to ‘High Five’ students, ask questions, and interact with individuals as much as possible in authentic ways (i.e., chatting when walking, encouraging when doing activities, using humour etc.) | Relationships |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Main, K.; Whatman, S.L. Christian Youth Adventure Camps: Evidencing the Potential for Values-Based Education to THRIVE. Youth 2025, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020036

Main K, Whatman SL. Christian Youth Adventure Camps: Evidencing the Potential for Values-Based Education to THRIVE. Youth. 2025; 5(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleMain, Katherine, and Susan L. Whatman. 2025. "Christian Youth Adventure Camps: Evidencing the Potential for Values-Based Education to THRIVE" Youth 5, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020036

APA StyleMain, K., & Whatman, S. L. (2025). Christian Youth Adventure Camps: Evidencing the Potential for Values-Based Education to THRIVE. Youth, 5(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020036