Could the Comfort Zone Model Enhance Job Role Clarity in Youth Work? Insights from an Ethnographic Case Study of the United Kingdom-Based National Citizen Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problems in the YW Field

“YW is defined by the Commonwealth Secretariat as all forms of rights-based youth engagement approaches that build personal awareness and support the social, political, and economic empowerment of young people, delivered through non-formal learning within a matrix of care”([1], p. 1)

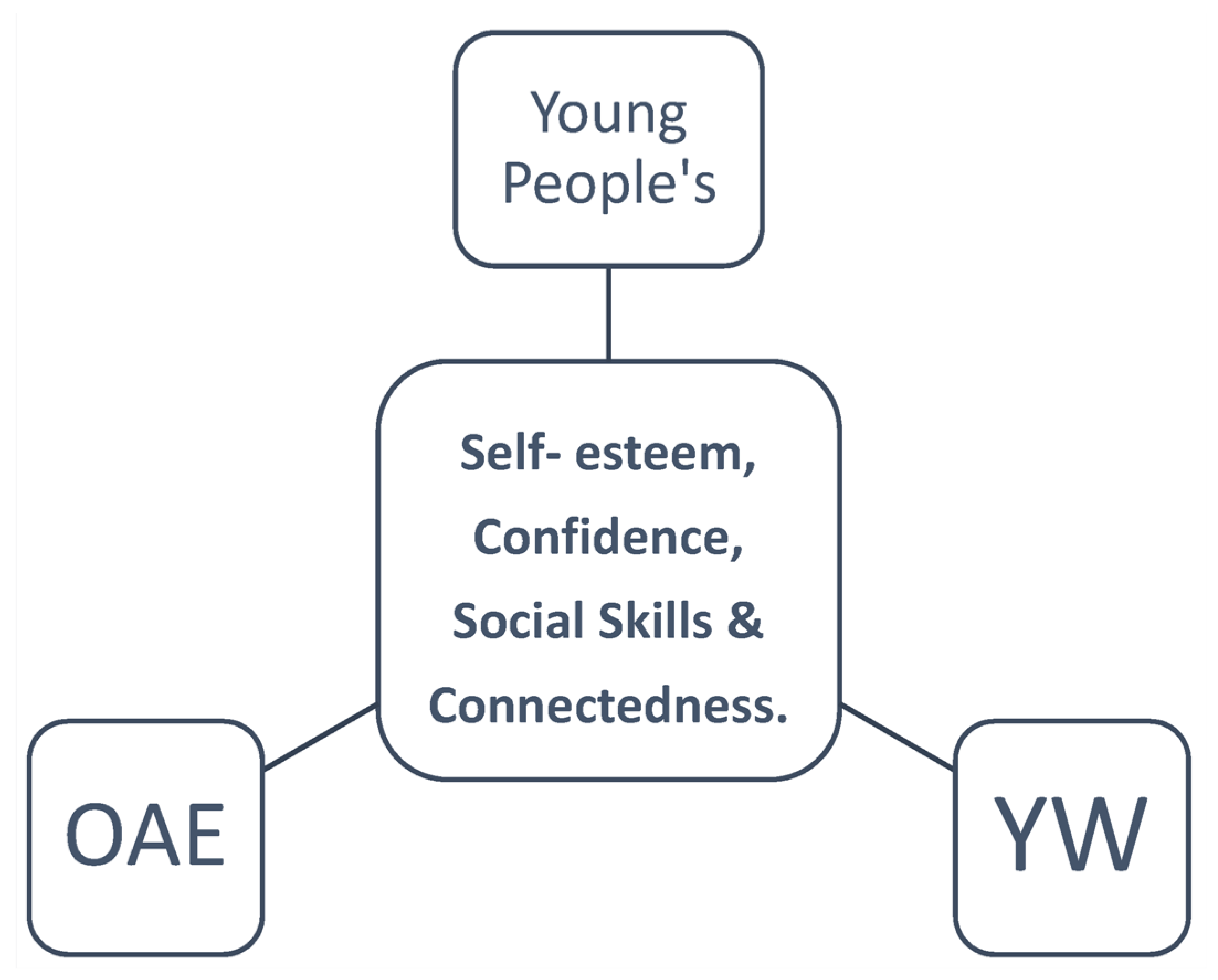

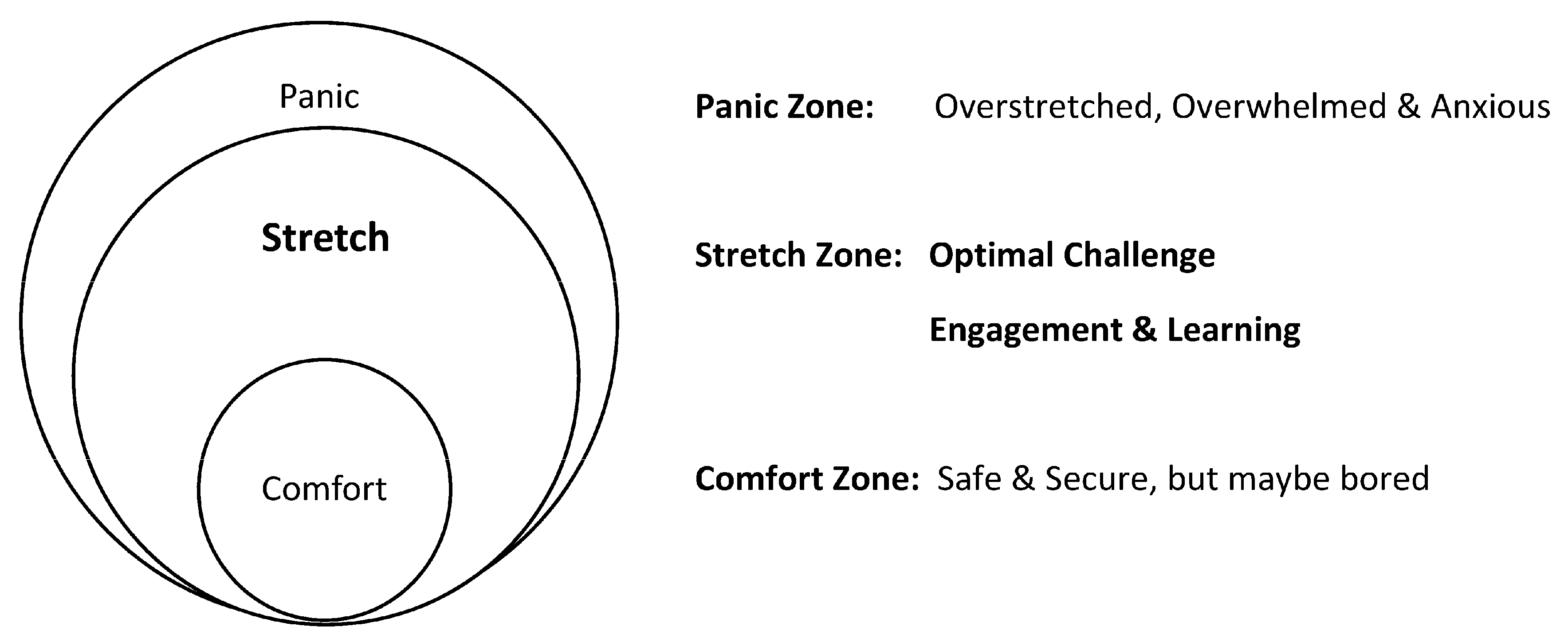

1.2. The CZM and OAE

1.3. Dewey’s Influence on OAE Conventions

1.4. Dewey’s Influence on the YW Approach

1.5. The NCS Case Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

2.2. Obtained Sample

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Positionality and Originality

3. Results

3.1. Theme One: The Experiential YW Approach

3.1.1. Subtheme 1.1: The Value of Experience

3.1.2. Subtheme 1.2: Leadership Style

3.2. Theme Two: What Is the Relevance of Stretch Learning to YW?

3.2.1. Subtheme 2.1: Capturing Complexity

3.2.2. Subtheme 2.2: The Benefits of Stretching

3.2.3. Subtheme 2.3: Risks of Stretching

4. Discussion

4.1. Theme One: The Experiential YW Approach

4.2. Theme Two: What Is the Relevance of the CZM to YW?

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commonwealth Secretariat (CS). Youth Work in the Commonwealth: A Growth Profession; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; Waite, C. From big society to shared society? Geographies of social cohesion and encounter in the UK’s National Citizen Service. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2017, 100, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, R.; Brown, A.A.; Winters, A.M.; Domiray, A. Trying to be everything else”: Examining the challenges experienced by youth development workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; DeMand, A.; McGovern, G.; Akiva, T. Understanding youth worker job stress. J. Youth Dev. 2020, 15, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S. Defining Adventure Education—A Reflection Paper. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2020, 20, 221–228. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343230441_Defining_Adventure_Education_-_A_Reflection_Paper (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Roberts, N.S. Outdoor Adventure Education: Trends and New Directions-Introduction to a Special Collection of Research. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.-B.; Lu, F.J.H.; Gill, D.L.; Liu, S.H.; Chyi, T.; Chen, B. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Outdoor Education Programmes on Adolescents’ Self-Efficacy. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2021, 128, 1932–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, T.; Pighetti, J.; Taff, D.; Allison, P. Outward Bound and outdoor adventure education: A scoping review, 1995–2019. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 143–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, H.E. The lasting impacts of outdoor adventure residential experiences on young people. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 2, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N.; Wong, J.S. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Wilderness Therapy on Delinquent Behaviors Among Youth. Crim. Justice Behav. 2022, 49, 700–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, D.; Gillis, H. A meta-analysis of outdoor adventure programmeming with adolescents. J. Exp. Educ. 1994, 17, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Connecting students to nature how intensity of nature experience and student age influence the success of outdoor education programs. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S.; Rodger, J. Evaluation of Learning Away: Final Report; Paul Hamlyn Foundation: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.phf.org.uk/publications/learning-away-final-evaluation-full-report/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- James, J.K.; Williams, T. School-Based Experiential Outdoor Education: A Neglected Necessity. J. Exp. Educ. 2017, 40, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, S.; Gass, M.A. Effective Leadership in Adventure Programming; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, S.J.; Cumming, J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Burns, V.E. Developing the Model for Optimal Learning and Transfer (MOLT) following an evaluation of outdoor groupwork skills programmes. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 39, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A.; Sibthorp, J. Outdoor Adventure Education: Foundations, Theory, and Research; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerkes, R.M.; Dodson, J.D. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. J. Comp. Neurol. Psychol. 1908, 18, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, M. From law to folklore: Work stress and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, P.; Cohen, G.L. If you’re uncomfortable, go outside your comfort zone: A novel behavioral ‘stretch’ intervention supports the well-being of unhappy people. J. Posit. Psychol. 2023, 18, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. Comfort zone: Model or metaphor? Aust. J. Outdoor Educ. 2008, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.J.; Allison, P. The perceived long-term influence of youth wilderness expeditions in participants’ lives. J. Exp. Educ. 2022, 46, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breda, A.D.; Theron, L.C. A critical review of South African child and youth resilience studies, 2009–2017. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 91, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breda, A.D. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Soc. Work 2018, 54, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, P.M. Questioning Tales of Ordinary Magic:Resilience and Neo-Liberal Reasoning. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breda, A.D.; Dickens, L. The contribution of resilience to one-year independent living outcomes of care-leavers in South Africa. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 83, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A.; Davidson, C. Behavior and Group Management in Outdoor Adventure Education: Theory, Research and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.S.; Davis-Berman, J. Positive Psychology and Outdoor Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohnke, K. Cowtails and Cobras 2: A Guide to Games, Initiatives, Rope Courses and Adventure Curriculum; Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rohnke, K. Silver Bullets: A Guide to Initiative Problems, Adventure Games and Trust Activities, 2nd ed.; Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, T.S.; Todd, S.; Breunig, M.; Young, A.B.; Anderson, L.; Anderson, D. The Effect of Leadership Style on Sense of Community and Group Cohesion in Outdoor Pursuits Trip Groups. Res. Outdoor Educ. 2008, 9, 7. Available online: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/reseoutded/vol9/iss1/7 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Hattie, J.A.; Marsh, H.W.; Neill, J.T.; Richards, G.E. Adventure education and outward bound: Out-of-class experiences that have a lasting effect. Rev. Educ. Res. 1997, 67, 43–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.W.; Johann, J.; Kang, H. Cognitive and Physiological Impacts of Adventure Activities: Beyond Self-Report Data. J. Exp. Educ. 2017, 40, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Smith, H. Everything we do will have an element of fear in it: Challenging assumptions of fear for all in outdoor adventurous education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2023, 23, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Education and Democracy. In An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, 1966th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. How We Think. In A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process; DC Heath: Boston, DC, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Collier edition first published 1963; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Nature; Dover edition first published in 1958; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K. Creators Not Consumers: Rediscovering Social Education; National Association of Youth Clubs: Leicester, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ord, J. Experiential learning in youth work in the UK: A return to Dewey. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2009, 28, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B. What Do We Mean by Youth Work. In What Is Youth Work. Exeter; Batsleer, J., Davies, B., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K. What is Youth Work? Exploring the History, Theory and Practice of Work with Young People. The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education (Infed). 2013. Available online: https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-youth-work-exploring-the-history-theory-and-practice-of-work-with-young-people/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Ord, J. Youth Work Process, Product and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K. What Is Pedagogy? The Encyclopedia of Pedagogy and Informal Education. 2012. Available online: https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-pedagogy/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Harris, P. The youth worker as jazz improviser: Foregrounding education ‘in the moment’ within the professional development of youth workers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2014, 40, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Taylor, M. Threatening youth work: The illusion of outcomes. Youth Policy 2013, 115, 104–111. Available online: https://indefenceofyouthwork.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/threatening-yw-and-illusion-final.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- De St Croix, T. Youth work, performativity and the new youth impact agenda: Getting paid for numbers? J. Educ. Policy 2018, 33, 414–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J. Innovation as a neoliberal ‘silver bullet’: Critical reflections on the EU’s Erasmus + Key Action 2. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2022, 43, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Audit Office. National Citizen Service Audit. 2017. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/National-Citizen-Service.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- De St Croix, T. Time to Say Goodbye to the National Citizen Service? Youth Policy. 2017. Available online: https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/time-to-say-goodbye-ncs/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Davies, B. Youth Volunteering—The New Panacea. In Austerity, Youth Policy and the Deconstruction of the Youth Service in England; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Kingdom Government. Policy Paper Youth Review: Summary Findings and Government Response, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/youth-review-summary-findings-and-government-response/youth-review-summary-findings-and-government-response (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- UK Parliament. National Citizen Service Trust Draft Royal Charter White Paper; Presented by the Minister for Civil Society. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/584139/NCS_Trust_Draft_Royal_Charter_white_paper_Commons_final.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- NCS|Grow Your Strengths|National Citizen Service (wearencs.com). Available online: https://wearencs.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Murphy, S.F. The rise of a neo-communitarian project: A critical youth work study into the pedagogy of the National Citizen Service in England. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2017, 16, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, K.; Frankel, S.; Faulks, K. Building the Big Society: Exploring representations of young people and citizenship in the National Citizen Service. Int. J. Child. Rights 2013, 21, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De St Croix, T. Struggles and Silences: Policy, Youth Work and the National Citizen Service Youth & Policy. 2011. Available online: https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/youthandpolicy106-1.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Mycock, A.; Tonge, J. A Big Idea for the Big Society? The Advent of National. Citizen Service. Political Q. 2011, 82, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K.F. Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L. “Outing” the Researcher: The Provenance, Process, and Practice of Reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramsci, A.; Hoare, Q.; Nowell-Smith, G. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci; Lawrence and Wishart: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- David, M.; Sutton, C. Social Research: An Introduction; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Location | Phases | No. of Days | No. of Nights |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Rural OAE facility | Adventure | 5 | 4 |

| A University Halls of Residence | Skills | 5 | 4 (Not observed) |

| A Youth Club Base | Social Action/ Volunteering | 5 | 0 |

| An Award Ceremony Venue | Accreditation | 1 | 0 |

| Participant Number | Age | Assumed Gender | Observed Ethnicity | Self-Reported Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | Female | Global Majority | Middle |

| 2 | 16 | Female | Global Majority | Middle |

| 3 | 16 | Female | Global Majority | Middle |

| 4 | 16 | Female | Global Majority | Working–Middle |

| 5 | 16 | Female | Global Majority | Working–Middle |

| 6 | 16 | Female | White | Working–Middle |

| 7 | 16 | Female | White | Working–Middle |

| 8 | 16 | Female | White | Middle |

| 9 | 16 | Female | White | Middle |

| 10 | 16 | Male | White | Refused to be Classified |

| 11 | 16 | Male | Global Majority | Refused to be Classified |

| 12 | 16 | Male | Global Majority | Working |

| 13 | 16 | Male | Global Majority | Middle |

| 14 | 16 | Male | Global Majority | Middle |

| Pseudonym | Age | Assumed Gender | Observed Ethnicity | Self-Reported Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colin | Undisclosed | Male | White | Undisclosed |

| Ben | Undisclosed | Male | White | Refused to be Classified |

| Lucy | Undisclosed | Female | White | Working |

| Bella | Undisclosed | Female | White | Middle |

| Sergio | Undisclosed | Male | Global Majority | Middle |

| Pseudonym | NCS Role | Self-Reported YW/OAE/Sports Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Colin | Director of the Youth Charity | Over 40 years of YW and OAE experience. |

| Ben | NCS Contract Manager | 11 years of YW and OAE experience. |

| Lucy | NCS Program Manager | 3 years of YW experience and a martial arts background. |

| Bella | Casually employed NCS cohort leader | Social work student with the experience of just one youth residential but otherwise no YW experience. |

| Sergio | NCS cohort sub-leader | 3 years of YW experience plus over 5 years of experience in sports coaching, personal training, and OAE. |

| Theme One: | The Experiential YW Approach | |

| Subtheme 1.1 | The Value of Experience | exemplifies how youth workers draw on lived experience. |

| Subtheme 1.2 | Leadership Style | illustrates youth workers’ non-authoritarian tendencies. |

| Theme Two: | Theme Two: What is the Relevance of Stretch Learning to YW? | |

| Subtheme 2.1 | Capturing Complexity | exemplifies how the CZM is a valuable tool. |

| Subtheme 2.2 | The Benefits of Stretching | illustrates the range of benefits, young people might gain from being stretched. |

| Subtheme 2.3 | The Risks of Stretching | demonstrates how dangerous coercion might be. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godfrey, N.M. Could the Comfort Zone Model Enhance Job Role Clarity in Youth Work? Insights from an Ethnographic Case Study of the United Kingdom-Based National Citizen Service. Youth 2023, 3, 954-970. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth3030061

Godfrey NM. Could the Comfort Zone Model Enhance Job Role Clarity in Youth Work? Insights from an Ethnographic Case Study of the United Kingdom-Based National Citizen Service. Youth. 2023; 3(3):954-970. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth3030061

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodfrey, Nigel Mark. 2023. "Could the Comfort Zone Model Enhance Job Role Clarity in Youth Work? Insights from an Ethnographic Case Study of the United Kingdom-Based National Citizen Service" Youth 3, no. 3: 954-970. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth3030061

APA StyleGodfrey, N. M. (2023). Could the Comfort Zone Model Enhance Job Role Clarity in Youth Work? Insights from an Ethnographic Case Study of the United Kingdom-Based National Citizen Service. Youth, 3(3), 954-970. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth3030061