1. Introduction

Populist understandings of sexting, cyberbullying, and nudes fail to address or demarcate consensual and non-consensual practices [

1]. The ramifications of disparate sexual double standards show that girls, in particular, experience harmful non-consensual practices. These practices include pressure/coercion/force/threat to produce images, the unauthorized distribution of sexualised images, and the non-consensual receipt or/and being shown person-to-person unsolicited sexualised images [

2,

3]. The absence of a feminist lens within early research to the nascent use of ‘catch-all’ terms, such as cyberbullying, nudes, and sexting, has simplified modalities of online sexualised and gendered violence. Indeed, research repeatedly shows that young people in Aotearoa (Aotearoa is the Māori name for New Zealand; Te reo Māori is an official language of Aotearoa New Zealand.) reject the term ‘sexting’ as it is considered an adult and media-driven term. Anecdotally, young people refer to cyberbullying, selfies, dick pics, and nudes [

4]. Resultingly, misconceptions have worked to promote abstinence and reduce education about digital sexual violence, which is often addressed generically as sexting by adults and/or cyberbullying/nudes by young people. These definitions that young people make meaning from are overlearned and, thus, embodied without question [

5,

6]. Through little fault of their own, they become complicit in adopting these terms, often without questioning sexualised and gendered harmful aspects. As a consequence, the seriousness of sexual abuse and violence that spans offline–online spaces can go unrecognised, be normalised, or be ignored by young people and adults alike [

5,

7,

8]

In youth digital sexual cultures, unwanted dick pics are indiscriminately referred to by young people as acts of sharing nudes and/or cyberbullying. Young people’s co-opting of these terms can obscure and minimize image-based-sexual harassment and cyberflashing (see [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]). In this paper, I position the receipt of unwanted dick pics from peers as ‘image-based sexual harassment’ and the receipt of unwanted dick pics from strangers as ‘cyber-flashing’ [

9,

10,

11,

12,

15]. In my reading of the data, if a male peer sent the unsolicited dick pic, girls were more likely to switch between the terms ‘nudes’, ‘dick pics’, and ‘cyberbullying’; whereas, images sent by strangers were referred to as ‘dick pics’. This paper focuses in the main, on peer-to-peer experiences; however, there is also reference to stranger cyberflashing experiences.

Young people report that the most prolific social media platforms used to cyberflash/send unwanted dick pics are Instagram and Snapchat [

11]. The non-consensual reception of dick pics is documented as a ubiquitous and routine experience that affects pre-teen and teen girls well before the age of 18 and, hence, is arguably normalised [

9,

10,

11,

15,

16,

17]. In terms of the prevalence of victimisation, research in the United Kingdom indicates that 75.8% of girls aged 12 to 18 have received unwanted dick pics [

10,

12,

13]. In Aotearoa, there is no prevalence-specific data for young people.

Feminist scholars Powell and Henry capture sexist and harassing actions online for women, such as unwanted dick pics, under the broad frame of technology-facilitated sexual violence [

17]. In addition to Powell and Henry’s framing, legal feminist research with adult women, conducted by McGlynn and Johnson [

15], successfully advocated for legislative reforms in England to officiate unsolicited dick pics under the term cyberflashing. As of March 2022, reforms have repositioned cyberflashing as a criminal act of digital indecent exposure, now considered as serious and harmful for girls and women.

Gohr [

18] argues that the concept of phallocentrism explains the act of sending dick pics as symbolising male privilege and entitlement. This, coupled with sexual double standards, illuminates why boys are less likely to be on the receiving end of any stigma or punishment around such acts [

9,

12]. Until recently, nascent findings about unsolicited dick pics mainly focused on the experiences of adult women (see [

14,

19]). Outside of the context of research, disclosures made by girls of having received unwanted dick pics have been symbolically silenced (see [

19]). With reference to teen girls and adult women, international evidence indicates that there are nuances to this phenomenon, which can be a consensual practice [

20,

21,

22,

23] or a form of non-consenting sexual harassment motivated by power [

19].

Motivations vary; it is reported that the unauthorised sending of a dick is considered a transactional strategy in an attempt to acquire nude images [

20,

21,

22]. The reception of unwanted dick pics has generally been researched within the cluster of sexting, which, in young people’s education, has also been conflated with cyberbullying [

5]; hence, it has also been explored under the term sexting (see [

20,

24]). Until recently, the sending and receiving of unwanted dick pics by boys have received little attention as a form of sexual violence. Due to normative gendered assumptions, boys’ perpetration of image-based sexual harassment has been attributed to cis-hetero masculinity and, as such, has gone relatively unnoticed [

25,

26]. While, reductively, public discourse considers the dick pic phenomenon humorous, the feminist reshaping of the sexting/nudes/cyberbullying discourse has identified this phenomenon of sending/receiving photos of penises as a further issue of non-consent [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In Aotearoa, Meehan’s 2022 research captures teen girls’ experiences of the ubiquity of unwanted dick pics/cyberflashing [

25]. Meehan, influenced by conceptualisations of sexual harassment and embodied safety work, positions the sending and receiving of unwanted dick pics as a form of intrusive digital marking of territory/space [

25,

27]. Meehan argues that teen girls consider themselves inherently responsible for managing the intrusion of such images with humour [

25]. These acts condition girls to the notion that a penis image is harmless and playful and, thus, downplay the territorial power threat associated with such an image. Academics have argued that heterosexual cisgender male social privilege positions this form of sexual harassment as a form of humour based on male bodies [

28,

29], which justifies the unsolicited sending of penis images as purportedly an ‘unthinking’ masculine action to be tolerated. This perspective normalises technology-facilitated sexual violence [

11,

12,

18].

The first theme in this paper navigates the peer-to-peer context of image-based sexual harassment. I explore how girls categorise and respond to receiving unsolicited dick pics and the safety implications with regard to the management of their gendered peer relations. In the second theme, I illustrate how the embodiment of postfeminist dispositions attunes girls to normalise and responsiblise themselves, such that the threats and consequences of image-based sexual harassment from peers and cyberflashing from strangers are de-escalated. I draw on Pierre Bourdieu’s toolkit of habitus, symbolic violence, and the field theory of practice, with Kelly and Vera-Gray’s concept of embodied safety work also included [

27]. I conceptualise the gendered strategies the participants use to manage digital sexual violations as a form of embodied safety work across offline–online fields [

27].

2. Methodology

2.1. Youth Participatory Research—#Useyourvoice Project

The integrity of research examining the experiences of young people is strongly upheld when young people are integrated into the design, analysis, and dissemination of a study [

30]. Young people have been at the vanguard of socio-digital transformations; yet, in initial research, they were rarely consulted on the questions researchers should be asking. To overcome this imbalance, I prioritised the use of qualitative feminist research praxis as an ethical orientation towards sharing power. This approach enabled the ‘voices’ of those who are typically structurally marginalised or excluded from research, such as young people, who are often homogenised, regulated, and studied down through the interpretive adult construction of adolescence [

31,

32]. To appeal to and encourage young people to speak out about their experiences, this exploratory research project was named ‘#useyourvoice’ and was designed in collaboration with young people over three stages.

The #useyourvoice project study collaborated with a wider cohort of 54 mixed-sex/gender students. The students attended one of four pseudonymised research sites, Acacia School, Birch School, Cedar School, and Deakin School. From the Acacia, Birch, and Cedar settings, the cohort who participated amounted to 46. These sites are mainstream schools whilst Deakin School was an Alternative Education Provision (Deakin School closed down following this study due to a reduction in state funding.). In Deakin, 8 students participated. All four schools were co-educational and located in the metropolitan city of Tāmaki Makaurau (In te reo Māori, Tāmaki Makaurau is the name for the city of Auckland.). Acacia and Birch were decile 10 schools whilst Cedar was a decile 6 school. In Aotearoa, school funding was allocated on a decile socioeconomic measure of the families living within the area of the school. Based on these measures decile 1 schools were awarded greater funding whereas decile 10 schools received lesser funding. This system was replaced in January 2023. Due to being an alternative education provision, Deakin had no ranking. These findings are based on discussions from friendship groups, with 13 girls in total, across Acacia, Birch, and Cedar, 1 of the participants who requested a semi-structured interview was recruited through a rainbow group at Acacia.

I obtained written consent from the principals, and from a parent/guardian, in addition to assent from the students. At all of the schools, I arranged for on-site trained counsellors to be on hand should any students need to discuss any information raised following the discussions.

Participation in the #useyourvoice project was agreed on an informal, voluntary, first-come-first-served basis. The inclusion criteria required students to be aged 13 to 16. Students excluded from participation were those who did not meet the age range, did not have parental consent, or were identified by pastoral staff as not being suitable due to personal or safety reasons. The research crossed a range of ethnicities: most young people identified as New Zealand European, followed by Māori, Pasifika, Chinese, Indian, South African, Spanish, German, and Russian. Most of the participants identified as cisgendered—meaning their gender identity conformed to their sex assigned at birth. Two students identified as non-binary. For anyone who identified as gender diverse or as non-heterosexual, there was also the option for one-to-one interviews and LGBQTI+ sessions. The themes generated by these young people made little specific mention of image-based sexual harassment or cyberflashing in reference to their gender and/or sexuality. This may be an area for further research consideration.

As part of the ‘#useyourvoice’ exploratory research project, all of the participants watched educational cyberbullying/sexting videos (the educational video resources used were accessed from websites (i) Childnet (UK), (ii) Office of the eSafety Commissioner (Australia), and (iii) Waka hourua website, which is no longer available (Aotearoa)). These videos were used as a springboard for our group/semi-structured interview conversations. Following the participants’ viewing of the videos, I referred to a framework of prepared questions, which posed to the participants their perspectives of the video vignettes. The participants could build on these conversations to present ontological perspectives. Within this approach, there was an exploratory scope for semi-structured discussion layering in nuance beyond the framework of questions. The framework of questions could also be referred back to should the conversation stray too far off-topic. This study did not expect young people to divulge highly personal information or experiences in which they had been traumatised, nor to unknowingly implicate themselves in criminal behaviour. Throughout this study, the focus/friendship groups lasted approximately 60 minutes. For ethical purposes, I purposefully did not ask the young participants any direct questions about dick pics or cyberflashing. I did this, in part, to ensure I did not introduce any new/unknown potentially harmful sexual content to them. Furthermore, the basis of this study was to tease out youth-centred meanings and understandings of cyberbullying, nudes, and sexting; therefore, I withheld as far as possible my adult-centric assumptions. To ensure a wide range of voices, a three-stage design ensured that young people were consulted during all stages to provide youth-centred voices and insights.

2.2. Stage 1—#Useyourvoice

In Stage 1 of #useyourvoice, I consulted, collaborated, and co-designed with the students from the alternative education provision (AEP). My collaboration with these students’ perspectives informed the subsequent design of Stages 2 and 3. The students at the AEP also participated as pilot participants. The students in the pilot/Stage 1 identified that, for the data collection in Stage 2, I should attend mainstream schools, dividing participants into single-sex, cisgender friendship groups of 3–6 friends. AEP students proposed this would enhance natural peer conversations owing to shared friendship history, safety, and familiarity among participants.

2.3. Stage 2—#Useyourvoice

For Stage 2, I negotiated access by written letters and emails to Acacia, Birch, and Cedar. At each school, I conducted two focus friendship groups, one week apart, with each single-sex, cisgender friendship group, as advised by participants in Stage 1. As previously stated, I offered semi-structured individual interviews for any participants who preferred a one-to-one setting.

2.4. Stage 3—#Useyourvoice

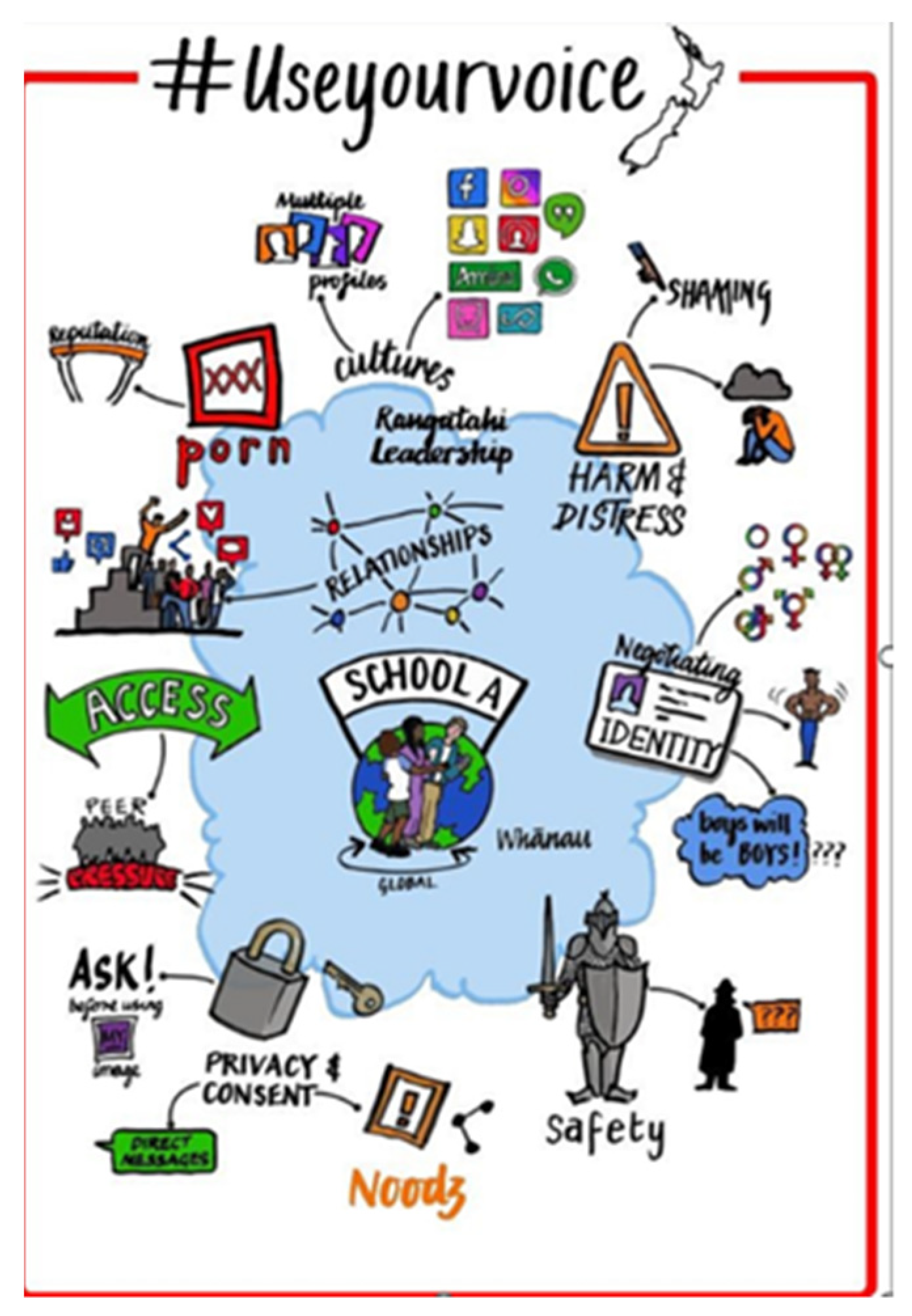

The rationale for Stage 3 was to ensure that participants from Stage 2 were involved in the co-construction of the final themes, following on from my pre-coding of the data [

33,

34]. The pre-codes were shared with a graphic illustrator, who captured the pre-codes themes and subsequently devised a poster for each school (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

For Stage 3, previous participants opted in to be part of a student expert review group to co-construct the themes. This proved a useful stage as the students reported back on my analytical pre-codes presented in the posters. The students noticed, for example, where I had missed a potential code or theme. It is of note that the pre-coding process did not draw out the themes of unwanted dick pics or cyberflashing. This theme was generated as a result of the Stage 3 review and my attendance to the data.

2.5. Analysis

The data were recorded on an audio device and transcribed verbatim. The data were uploaded onto NVivo software and the participants’ names were assigned pseudonyms. The data analysis was informed by a reflexive thematic analysis approach [

34] underpinned by Braun and Clarke’s six phases of thematic analysis: (i) familiarisation, (ii) generate pre-codes, (iii) generate themes, (vi) review with students, (v) overall story of the themes, and (iv) select extracts to illustrate the story [

35] (p. 87). I was critical of cyberbullying, nudes, and sexting epistemology and was informed by curiosity and a willingness to explore with the analysis. In addition to listening to and reading what had been said, I paid attention to what had been omitted or hinted at as unspeakable. At all stages, I was open to the uncertainty of what was generated. This was critical as some subjects were not explicitly stated, such as experiences of cyberflashing and receiving unwanted dick pics. These experiences emerged through allusion and subsequently generated the central theme of peer-to-peer image-based sexual harassment and cyberflashing.

2.6. Theoretical Framework

Feminist scholars have contemporized Bourdieu’s social theory of constructivist structuralism. By incorporating a broad feminist lens, some have applied Bourdieu’s conceptual toolkit, consisting of the gendered habitus, capital, social fields, and symbolic violence [

36,

37,

38,

39]. This lens bridges structure/agency and subject/object binaries; the ‘lived experience of the world is incorporated and realized’ [

36] (p. 98). Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’ is a ‘way of doing and being not a matter of conscious learning, or ideological imposition, but is acquired through practice on account of lived practice’ [

39] (p. 27). Habitus is both unique to individuals and shared across different groups; it is the embodied dispositions of power relations and/or a sense of individual or shared mastery or technique [

40] (p. 99).

With respect to young people, their habitus as gendered and digital is an apt conceptualization to encapsulate the rapid technosocial changes they have collectively experienced. Individually and collectively, their digital-social practices have evolved to the integrated digitization of offline–online spaces [social fields] with their use of smartphones, social media applications/platforms, and the Internet of Things. Socially, young people’s gendered and sexual power relations operate across these devices, affordances, and spaces as individuals and peers.

The digital gendered habitus is generated by and generates dispositions constituted by discourse or what Bourdieu would refer to as doxa. Conceptually, doxa refers to legitimated beliefs which produce and reproduce arbitrary categorisations and norms [

41,

42]; indeed, Bourdieu argues invisibilised masculine domination is doxa [

43]. In this context, doxa can apply to categorisations and accepted norms about non-consensual digital sexual cultures involving cyberbullying, nudes, and sexting as acceptable. These norms are collectively accepted, being perpetuated often by governments, education, media, social media, families, and young people and often being attributed to technological determinacy, rather than gendered socio-cultural drivers (see [

7,

44]). For example, official definitions of cyberbullying, especially for young people, pay little attention to the influence of cultural/gendered scripts and norms and rarely reference them as technology-facilitated sexualised violence [

17]. As a consequence, and due to dominant doxa, young people, misrecognize cyberbullying and nudes as technology-facilitated sexual violence as they view this as less-than sexual and/or physical violence (see [

45]). In neoliberal postfeminist times, the emergence and acceptance of new femininities have shaped an ‘empowered’ self-surveillant subjectivity [

46]. Due to the postfeminist ‘corporeal inculation’ [

36] (p. 99) of this ‘empowered’ subject, gendered dispositions modernise and comply with the demands of digital-social conditions. Without recognition, the gendered digital habitus complicity manages the tasks of embodied safety work illustrating symbolic violence.

3. Findings

These findings are organised under two overarching headings with sub-themes:

‘navigating the peer-to-peer context of image-based sexual harassment’ and ‘safety work: ignore, engage, unfollow, block, report, repeat’.

3.1. Navigating the Peer-to-Peer Context of Image-Based Sexual Harassment

When analysing the audio and the transcriptions, I noticed a recurrent theme across the girl groups. Generally, when asked to give examples of ‘nudes’ and ‘cyberbullying’, the girls addressed incidents in which they and their friends had received unwanted sexualised images from strangers and peers. Therefore, when the girls discussed cyberbullying and nudes, I needed to disentangle what they meant by the term and what their use of it could signify. It seemed they were sometimes referring to unsolicited dick pics from strangers and at other times referring to unsolicited dick pics from male peers. In context, the distinction between strangers and peers was relevant as the girls perceived the sending of an unwanted dick pic by these different parties as underpinned by different motivations (see [

22,

47]). Throughout this paper, I interchangeably use the terms ‘unwanted dick pics’, ‘unsolicited dick pics’, and ‘image-based sexual harassment’.

Normalisations, Annoyance, and Fear of Reprisals

Universally, in this study, girls used the terms ‘nudes’ and ‘cyberbullying’ to describe digital sexual acts/experiences; however, when we unpacked these words, they made a contextual distinction. Once they had raised the phenomenon of the unwanted dick pic, they bifurcated the reception of unwanted images into two categories. Images were either sent by strangers—perpetrators informally described as ‘old perverts’—or by male peers. The designation of ‘peer’ was harder to define as it was dependent upon both the receiver’s relationship with the sender and the sender’s social status. Similarly to findings in existing research, the girls in this study reported that unwanted dick pics from peers and strangers were ubiquitous (see [

9,

11,

12,

16]). Starting this passage, Livvy, Ashley, and Talia initially hesitate to say the term ‘dick pic’ aloud; they indicate that the normalisation of dick pics is a part of contemporary girlhood:

- Emma:

It’s okay to say it [dick pics]. Because I didn’t want to say it [dick pics], just in case you’ve not heard of it. But you have heard of it.

- All:

Yes. [Loudly, in unison.]

- Livvy:

Too much!

- Emma:

Too much, okay. Is that something that’s normal, that gets…

- Ashley:

It gets talked about.

- All:

Yes.

- Livvy:

Yes, unfortunately.

- Emma:

What happens? Is it between friends or…?

- Talia:

I’ve never seen one [a penis] in like, real life but…

- Livvy:

I haven’t seen one in real life [a penis], but I’ve been sent them.

Livvy, Ashley, and Talia confirmed that the subject of seeing a penis via digital affordances is widely discussed and that routine exposure to unwanted dick pics is unfortunate but normalised. Our discussion revealed that these girls’ first experiences of seeing a penis was through a screen. What struck me with this conversation was that the girls did want to openly discuss these experiences, despite their hesitations. Unfortunately, however, as they explained during the session, they felt unable to do so due to a culture of silence from adults. In effect, the girls apparently conceal their experiences with dick pics to avoid judgment or victim blaming; this amounts to a form of social silencing. There are limited institutional reporting systems or social support systems in place for them and their experiences of such image-based sexual harassment and cyberflashing are overlooked. Research has shown that cultures of silence, which disallow or discourage girls from discussing such violations, perpetuate both a broader acceptance of online sexism and the victimisation of girls [

48]. This group of girls was not the only one that implicitly understood that it was better to stay silent on the subject of peer-to-peer image-based sexual harassment and stranger cyberflashing.

The passage that follows was recorded after the formal group interview with this group of girls had concluded. I had turned off the recording device and, as I was packing things up, I could hear the girls chatting in the background. The group were complaining about ‘F-boys’. The ‘F’ is their abbreviation of the word ‘fuck’ and colloquially describes a gendered trope of a boy who performatively exhibits heterosexual, cisgendered idealised masculinity, the display of which reinforces dominant sexual and gendered peer relations [

49]. Hearing this background chatter from the girls about F-boys, I ask the group if I can turn the recording device back on to capture their thoughts on this subject, recognising the way the subject seemed to be related to digital sexual cultures:

- Emma:

Could you be an F-boy online?

- All:

Yeah.

- Ariana:

They send dick picks of themself.

- Martha:

I have this story. There was this guy, and you know how you get stories, like, on Instagram?

- Emma:

Yep.

- Martha:

So, I’m, like, DMing [direct messaging] because I’m bored, and I want to talk to someone, and he was like, ‘Hi.’ I was like, ‘Hi.’ And then he just sent me his dick pic, and I was like, ‘I did not ask for this!’

As the narrative continued, it became evident that once Martha received the unsolicited dick pic from her male peer, she messaged her friend, Piper, to inform her about the image-based sexual harassment. On receiving Martha’s direct message about the unsolicited image, Piper was angry and took on the role of an active bystander to support Martha. Piper challenged the sender of the unwanted image, whom the girls knew when he previously attended their school, by sending him a direct message (the boy had since moved to a different school):

- Piper:

I texted him. I got really salty [irritated]—and he was like, ‘You’re a lot calmer than your friends.’ I’m like, ‘What?!’

- Martha:

Yeah, and I know that person has done it [sent dick pics] to so many of my friends as well, and no one needs it. If you [the receiver] didn’t ask for it, you [the sender] shouldn’t be sending that.

- Piper:

I was like, ‘STOP sending stuff to my friends…’

- Emma:

What happened then—you said earlier that he moved schools, why did he move—because of this?

- Martha:

No, he sent them [the dick pics] while he was over there, but when he was here [before moving schools], he was always, like, kind of inappropriate.

- Emma:

Does that get reported to somebody at school?

- Martha:

I don’t know, because I, like, I know him. So it’ll be awkward if I see him, and it’s like, ‘You reported me, I’m going to get my boys on you.’

- Emma:

Do you think his actions relate to sexual violence?

- Martha:

Yeah, it’s just there, like… [pause] you can’t… [trails off]. If you see him in public, then it could…

Here, Martha paused again and Piper interjected. Piper went on to describe her continuing message interaction with the peer who had sent the unwanted dick pic to Martha. Piper relayed the messages that she sent to the sender:

- Piper:

People [signifying girls] say they don’t want to see your nudes [dick pics], but you send them anyways.

- Sender:

[Verbalised by Piper] Is that true? I don’t give a crap.

Piper then returned to the current conversation with me and the rest of the group:

- Ariana:

I don’t understand why guys send it, like, what do they think, like, girls are going to react? Do you think girls are going to like that? Do you think girls are going to be like, ‘Oh yeah, I totally want to get with you now’? What is going on? [Angry]

- Martha:

And if you just straight up send it, like without even getting to know that person, like not having a conversation, obviously, they’re not going be happy about it, they’re going to be like, ‘That’s a bit weird’.

- Emma:

Do you think boys feel under pressure to send images?

- Ariana:

Well, clearly not! They’re sending it multiple times to girls when they just want to say hi. You would think about it twice, wouldn’t you?

It was clear that the girls were frustrated at the intrusion caused by a boy sending an unsolicited dick pic. Ariana guessed that the sender’s motivation might have been a method of online transactional flirtation; research suggests that, for boys, sending a photo of themselves can sometimes be a prerequisite to making a request for a girl’s nude image (see [

9,

12]). The way that Piper described the sender and his unwillingness to apologise for sending the image seems to express a sense of entitlement in the boy. Despite Piper, as a third party to the conflict, urging him to desist from sending unwanted images, the sender did not seem to connect his actions to image-based sexual harassment or to non-consensual action that violates the recipient.

The girls’ conversation made clear that this male peer, who had sent dick pics on multiple occasions, was known to the friendship group. However, Martha did not (and neither should she be expected to) elaborate on the nature of this peer relationship to identify whether her friendship with him was intimate or not. During the general discussion, the girls framed this encounter as an example of boyish belligerence and indicated, through their unwillingness to report it, that the consequences of doing so would be more worrying to the girls than any consequences associated with cyberflashing from strangers. Martha articulated the unease she would feel if she were to confront the victimiser or report the unwanted images to school authorities. She indicated that taking such actions could potentially result in digital sexual violation online that could leak to terrestrial spaces. For Martha, corporeal encounters with peers in terrestrial spaces who have perpetrated image-based sexual harassment present a sense of unease.

This unease may be due to the dispositions seated in the gendered habitus, which naturalises, for girls, the inevitability of impending male sexual violence. This conditioned sense of inevitability means that girls pre-consciously adapt to threats in their personalised and public environments (offline–online fields) without necessarily being cognisant of the adaptations that they are making (see [

37,

38]). For example, as a consequence of experiencing image-based sexual harassment, Martha might modify her regular local walking routes or sit in a different place on a school bus to avoid a peer; she may also try to avoid a person of threat at school. Online, she may withdraw from a social media platform or from group messages (see [

50]). Early on, the gendering of the habitus attunes girls to embody these types of safety work; so, it is logical that Martha, because of the likely and complex consequences to her physical and online peer relations and the threat to her own safety, would be reluctant to report the sender of the unwanted dick pics.

The sending of unwanted dick pics is an example of a non-consensual digital sexual violation that is forced upon girls. Martha and her friends shared that they de-escalate such situations by ignoring the unwanted dick pics and the messages in the hope that doing so will keep them safe from physical reprisal (even though this may not necessarily prevent online retaliation). Ironically, not reporting might backfire as, if the acts are eventually discovered, adults might question (victim blame) why it is that Martha did not or would not report the peer’s perpetration of image-based sexual harassment. Parents or guardians might also respond to the complaint by restricting Martha’s access to social media platforms. Consequently, we can understand how, for girls, it is risky to report image-based sexual harassment to adults. It makes sense for Martha and her peers to de-escalate such situations by ignoring or staying silent about image-based sexual harassment, not only to avoid a potential threat from the male peer[s] but also to reduce the likelihood of any device restrictions placed upon them or excessive surveillance by concerned adults.

3.2. Safety Work: Ignore, Engage, Unfollow, Block, Report, Repeat

Compared to their male counterparts, young women in Aotearoa are higher users of social media and, specifically, more frequent users of Instagram and Snapchat [

51]. This emphasis on these two central social media platforms is meaningful because they are key sites on which cyberflashing and the sending of unwanted dick pics are perpetrated [

10]. The strategies that some of the girls in this study embodied to deal with daily intrusions, which often occurred on social media platforms, followed a logic of ignore, unfollow, block, report, and repeat. Because image-based sexual harassment is considered to be cyberbullying and/or nudes, thus being minimised, a recurrent theme was the normalisation of the underreporting of image-based sexual harassment and stranger cyberflashing. Research has also shown that when girls take action to report cyberflashing and image-based sexual harassment perpetrated through the affordances of social media platforms, the operators of these platforms are often unresponsive to the girls’ disclosures. For girls, this ‘corporeal inculation’ [

36] (p. 99) can confirm the awareness of the gendered habitus that boys and men dominate, controlling offline–online spaces in the same way they do physical public spaces. The lack of any response from the social media platforms to complaints makes it clear to girls that those in charge have little intention of addressing the affordances that enable cyberflashing and image-based sexual harassment. Throughout girlhood, one’s gendered habitus takes on the gendered duties of safety work that are both invisible and integral to the embodiment of being a girl or young woman [

27,

50]. Because social media platforms do not police the male intrusion inherent in the unwanted receipt of dick pics, females are tasked with doing their own safety work, associated with responding to the sender of dick pics and de-escalating the intrusion. I transfer Vera-Gray and Kelly’s logic of embodied safety work to integrated offline–online spaces [

27,

50,

52].

Cultural Pressures and ‘Safety Work’

In the exploration of digital sexual cultures, the use of an intersectional lens, that is, the convergence of cultural context with identity, gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity, and disability, can provide nuanced insights about the risks facing different groups of young people, particularly girls (see [

10,

53]). The subsequent passage attempts to present the nuances of some of the cultural pressures experienced by young women concerning image-based sexual harassment.

Lakshmi, Preeti, Sudha, and Lata, girls of Indian backgrounds, explained to me how, for some ethnic and faith-based communities, photographic images, as artefacts of cultural symbolism, can take on meanings that are different to a Westernised understanding of such images. This group explained to me how the act of taking a selfie [non-sexualised] was considered by some members of the orthodox Muslim community, including their own family members, as a breach of the Qur’an (see [

54,

55,

56]). None of these young women subscribed to these orthodox beliefs; however, their insights opened a conversation about the layering of cultural pressures and taboos that might be experienced when one is participating in digital sexual cultures or experiencing non-consensual digital sexual violations. These cultural influences, for some communities of young people, might add barriers to the reporting of sexual violence that has happened across offline–online spaces (see [

57]). In this exchange, Sudha apprehensively referred to the experiences of one female friend who had received an unwanted dick pic from a male friend:

- Sudha:

One of my friends—someone sent her a photo, but she just blocked him.

- Emma:

Was that by somebody that your friend knew?

- Sudha:

Yeah, at school.

- Emma:

Was it something to do with nudity?

- Sudha:

Yeah.

- Emma:

Was it a dick pic?

- Sudha:

Yeah. [All the girls giggle nervously.]

- Emma:

It’s okay, dick pics have been previously mentioned in other groups. Did these friends know each other?

- Sudha:

Yeah.

- Emma:

What kind of relationship did they have?

- Sudha:

Friends, I think, just, like, talking.

- Emma:

Do you know what happened in that situation?

- Sudha:

He called her, like, not mature for blocking.

- Emma:

So, he sent the pic and then, because she blocked him, he said she was immature?

- Sudha:

Yeah.

- Emma:

Is that cyberbullying? [Our wider discussion up to this point has been about cyberbullying]

- All:

Yeah.

- Emma:

Do you know what happened?

- Sudha:

I don’t think it got reported. She just blocked him.

- Emma:

Is it distressing to receive these images?

- Sudha:

Kind of, it is.

- Lakshmi:

I think, because, it’s like, once you see it, you can’t un-see it.

- Emma:

How would you feel if that happened to you?

- Lakshmi:

Like, ashamed.

- Sudha:

Grossed out.

- Preeti:

Traumatised, ashamed.

- Lata:

Awkward.

- Sudha:

Because they’re showing, like, content that’s offensive.

- Emma:

What about reporting unwanted nudes?

- Sudha:

Some people would be scared that their parents would find out.

- Preeti:

Or it could be they’re blackmailed or something, and if they did report they’re going to get in more trouble.

- Lakshmi:

People who follow religion or culture, they would be more scared to report because they might fear that they’d be abandoned by their family.

In this conversation, Sudha explained that her friend, who had been subjected to image-based sexual harassment by a peer, took action by blocking the peer from her social media contacts. The male friend, who had sent the unwanted dick pic, responded by gaslighting Sudha’s friend; he minimised his perpetration of image-based sexual harassment and repositioned her response as an ‘immature’ overreaction.

Across this study, the girls described blocking—rather than reporting—as a common form of safety work. This act is a sensible one; blocking immediately removed the risk of that particular person sending more unwanted images from the account they had used in that instance. The girls shared perceptions that reporting, on the other hand, even if completed confidentially, could increase the risk of confrontation if the peer-sender lost access to his account as a consequence and, therefore, suspected who had made the complaint.

The internalisation of postfeminist dispositions to be a strong girl and reject victim status could leave girls, such as those in this group, questioning whether their experience would be considered by society to be as harmful as it felt [

58,

59,

60], especially if they were being gaslit by the perpetrator. Existing patriarchal dominant gendered power relations may also cause girls to second-guess whether they had indeed experienced sexually harassing violations as harmful, rather than as normal male behaviour. This process of recognising and embodying a violation but justifying such experiences of male domination as ‘the way things are’ (which Bourdieu would term as doxa), further explains why such encounters are deemed to be not worth reporting. This fortification of the status quo, in which there is an accepted power differential between males and females, exemplifies Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence [

43].

For girls who experience image-based sexual harassment, being ‘good’ and learning to practice silence are important strategies; girls may use silence strategies to prevent the risk of sexual stigma. Indeed, Preeti and Lakshmi suggest that, for girls raised in some ethnic communities, there may be amplified cultural and gendered pressures to assess before taking any informal or formal action in response to having experienced technology-facilitated sexual violence. The girls hinted at familial responses in which the consequences of being subjected to an unwanted dick pick from a peer might also result in the girl being victim-blamed and, in worst-case scenarios, ‘abandoned’ by family and support networks.

The dialogue between the girls suggested that the community policing of female sexuality takes precedence over the reporting of experiences of victimisation. Other explorations with women in ethnic minority communities in Aotearoa have shown that, following an experience of sexual violence, it can be risky for the victim to disclose the experience or reach out for support. The group’s concerns substantiate these observations and help to explain the underreporting of incidents of sexual violence by young women in these communities (see [

57]). When I reminded the girls that we were discussing the topic of ‘cyberbullying’ by asking whether they would place experiences of receiving an unsolicited dick pic into this category, they all confirmed that they would. Certainly, in these circumstances, categorising any form of technology-facilitated sexual violence as ‘cyberbullying’ makes good sense. In doing this, the girls reduce the broader risks associated with sexual stigma and gendered sexual double standards that arise from being exposed to these unwanted images.

3.3. Cyberflashing: We Started Messing with Him

Some of the girls in this study reported purposefully engaging with cyberflashers as a perceived attempt to take back some control over the intrusion by toying with the perpetrators. In the following passage, Kelly nonchalantly recalled being cyberflashed by a stranger and explained the ways in which she and her friend engaged with him:

- Kelly:

I actually recently got one.

- Emma:

What did you do?

- Kelly:

My friend took my phone, and we started messing with him. We didn’t send anything, photos or anything, but we were like, ‘Ha, funny…’

- Emma:

Is there anywhere to report those type of pictures?

- Kelly:

Yeah, but I don’t think Instagram does anything about it. There’s a report button and it says: ‘What did you not like? Was it inappropriate? Was it spam?’ You put it in, but I don’t think anything happens. I think accounts have to get three reports until they get it [the image/or the account] taken down.

Here, Kelly explained how she and her friend resignified the digital sexual intrusion as an amusement. Similarly to women’s use of humour to belittle the senders of dick pics, as described in research by Amundsen [

23] and Meehan [

25], the girls in this study indicated that they use humour as a tool to distance themselves from the violations. On the surface, the use of humour as a strategy to respond to digital sexual intrusions could raise the question of how harmful this encounter genuinely is. The response by Kelly and her friends to push back by messaging the cyberflasher likely serves as their gendered strategy to redefine an uncomfortable situation as a playful encounter.

In reference to street harassment in terrestrial public spaces, Vera-Gray and Kelly [

27] conceptualise the ways females respond to violations as part of the invisibilised social conditioning of girls and women. Girls learn, through repetition, to normalise prevention and avoidance, ultimately learning to dismiss harassing experiences, such as receiving unwanted dick pics and cyberflashing, as ordinary. Eventually, these responses are embodied in the gendered habitus as common sense (see [

27]). According to Bourdieu’s theoretical concepts, this process of gendered embodiment captures doxa and symbolic violence.

Bourdieu would frame the ways in which girls and women pre-consciously embody the doing of safety work as arising from the gendering of the habitus. The spaces in which females now have to partake in safety work have expanded into the digital realm. On the surface, it appears that by joking around with the intentions of the cyberflasher, Kelly and her friends are demonstrating agency because they do not explicitly describe themselves as passive or victimised. This serves as a further example and a powerful reminder of Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of symbolic violence. Unknowingly complicit in an act of digital resistance, Kelly and her friends perceive their engagement with the cyberflasher as a practice motivated by free choice (see [

61,

62]).

Kelly’s story also reveals her familiarity with Instagram’s self-regulated three-strikes reporting process—and its ineffectiveness. The fact that the community standards of social media platforms consider it acceptable for girls to have to endure a first and second exposure to a violation of their safety before they can make a report is incomprehensible, given that the phenomenon is so widespread. Kelly’s recognition of the futility of reporting to social media platforms is well substantiated (see [

10]). The encounters, which seemingly have no consequences, contribute to a gendered and sexual doxa that perpetuates gender order and gender inequality by affirming to young women that cyberflashing and image-based sexual harassment have become legitimised as accepted and acceptable practices of male dominance in digital spaces. Doxic norms confirm and support the interpretation of digital sexual violence as natural and male intrusiveness as normal. Girls are limited to terms like ‘cyberbullying’ and ‘nudes’ in any discussion of digital sexual violations [

63].

Kelly expresses distrust in the ability of social media platforms to prioritise her safety. She is not alone in her scepticism of the capacity of social media platforms to address online misogyny and sexual harassment. Studies in the United Kingdom show that only 10% of children and young people understand how to report distinct categories of harmful online content and only 43% of 8 to 17-year-olds believe that reporting harmful content would result in any action being taken [

64]. Because social media platforms do not demonstrate a readiness to protect them, logically, some girls choose to take charge of the intrusions by turning the situations around for their own amusement. The gendered habitus has a feel for the game, so to speak, and therefore makes decisions based on the expectation that nothing will be achieved by reporting to social media platforms. The gendered habitus senses this because, as Bourdieu argues, it is conditioned to expect these outcomes based on past experience and outcomes [

65]. As such, the gendered habitus guides the girls’ logic that considers playing with a cyberflasher as a demonstration of agency. In ‘postgirlpower times’, it is critical to unpack the context and logic of enactments of determination by girls and acknowledge that girls are most likely acting not as agents or victims but as ‘suffering actors’ [

60] (p. 46) attempting to disrupt gendered power imbalances in the cultural digital sexual landscape within which they are operating.

The girls’ knowledge that their reports to social media are unlikely to receive a response to complaints of sexual harassment not only justifies their emerging distrust of the inept reporting systems of social media but also has much broader implications for the (under) reporting of sexual violence. Findings from the Safer Internet Centre in the United Kingdom indicated that 44% of children and young people used platform-blocking mechanisms [

64]. Such mechanisms provide some young people with a perceived amount of control over their exposure to online harm and digital sexual violations. Although blocking may be a helpful strategy (despite the fact that it can only occur after sexualised harassment has been perpetrated), participants indicated their reliance on blocking meant they were unlikely to make a full report of their experience. As a result, reported rates of image-based sexual harassment and cyberflashing are likely to be highly inaccurate.

3.4. Maybe I Should Unfollow Him

Across this study, girls described not only being confronted by snapshots in person and on social media messaging apps but also being affronted by the live-streaming of dick pic videos from male peers. In the following discussion, the group explained how the default setting for following a friend on Instagram, Instagram Reels, makes the viewing of their friend’s real-time footage automatic. Under this setting, it is difficult to avoid exposure to an Instagram contact live-streaming a video of his penis. As previously noted, in the context of postfeminist dispositions, it is common for the gendered habitus of girls to internalise the responsibility for doing their own safety work. If image-based sexual harassment cannot be prevented, then it is up to the girl to avoid the peer or ignore the image/video. However, when the context of space and time are collapsed (see [

66]), as they can be in offline–online contexts through online live streaming, it can be impossible to prevent the viewing of unwanted digital sexual images.

Lauren, Millie, Trudy, and Brianna recounted how, amid their routine daily activities, this disturbance is experienced as an enduring mental invasion for them and other networked spectators. The girls explained that their response strategies are to unfollow or block the peer to prevent future encounters and described the complications of friendship networks. They acknowledged that the incident is harassment, but, not particularly of themselves. By focusing their expressions of concern on others, they shift the consideration of this encounter as a form of their own victimisation:

- Lauren:

I’ve seen somebody who I followed—he had a livestream of him taking off his pants and showing a dick pic.

- Emma:

Is that somebody who’s a teenager?

- Lauren:

Yes.

- Emma:

Is that somebody who is known to you?

- Lauren:

Yes.

- Emma:

When he did that livestreaming, what do you do in that type of situation?

- Lauren:

I go and unfollow them.

- Millie:

Yeah, I block them.

- Brianna:

Yeah, I just unfollowed him, blocked him.

- Emma:

For livestreaming, would you also consider that to be sexual harassment?

- Millie:

Kind of, because it was his [mouths the word penis]—him putting it up there, and it’s like…

- Brianna:

And you might not want to see it.

- Millie:

And he put it up there. I mean, it is kind of harassment for the other people who clicked on it, because they’re like, ‘He’s my friend’, and then they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s his… [penis]’ It’s a bit of shock because I don’t want to see that—that’s mentally scarring.

- Brianna:

Some things just can’t be unseen. [Girls from Cedar School also said this.]

- All:

Yeah, definitely.

As far as we can surmise in the above description, the live-streaming of the dick pic was not targeted at any particular individual but shared in the context of a networked peer audience [

67]. However, as we have heard in an earlier account, boys understand there are unlikely to be any consequences for this digital exhibitionism. Bourdieu would tell us that this absence of penalty is due to the symbolic force of androcentrism that results in domination either going unseen or being naturalised [

43,

62]. The influence of symbolic violence could be used to explain the fact that the girls do not express views that such experiences of digital exhibitionism are explicitly dominantly sexist, gendered, or violent actions. Instead, as you will hear, they privilege the rights of their male peer to choose to live-stream his penis, despite it being likely that this will force some viewers into a digital sexual encounter. It is worth noting that, in the following extract, they did classify the live-streaming as age-inappropriate content:

- Emma:

Did you find it distressing when you clicked on it?

- Brianna:

I was like, well, this is his choice, I guess—maybe I should unfollow him.

- Millie:

He should have put a warning up.

- Brianna:

Warning: sexual content. R18.

- Millie:

It’s his choice to put it up there. Or did he just, like, pop it up?

- Brianna:

He had, like, a computer…

- Millie:

Well, if it was him putting it up there with his own ‘I want to put that up there’, then that’s totally okay for him, but he should have let everyone know that clicked on: ‘Hey, guys. I’m about to show my… [penis] If you don’t want to see it, then bye.’

By indicating that their male peer has a right to exploit the affordances of social media for the purposes of showing sexual images of himself, the girls appeared to accept the fleetingness of oversharing as a norm on social media platforms (see [

68]). Despite the fact that the act results in the digital penetration of their personal space, the girls upheld their male friend’s prerogative to live-stream his penis.

In this following dialogue, Talia explained that her solution to receiving a dick pic is to decline message requests. Again, this strategy can only be employed after the viewing of a digital sexual image; so, declining message requests cannot help girls from being forced, without the choice of consent, to view unwanted and unexpected images of penises. Talia and Livvy reasoned that, because declining message requests from the sender of an image results in the image being permanently deleted, declining is a sufficient intervention. However, this strategy does not prevent the girls from receiving unwanted dick pics from other people in the future:

- Livvy:

Yeah, it’s in your message … Because my accounts are private, so it comes up with one message request, and then you click on it, and then: dick pic.

- All:

Yeah.

- Emma:

When you see those, do you consider that to be part of cyberbullying or harmful in a sexual way? [Our wider discussion up to this point has been about cyberbullying]

- Talia:

Kind of, but you can easily decline it.

- Livvy:

Yeah, you can decline it, and it’s gone forever.

- Emma:

What about if you’ve never seen that, and then it just happens for your first time, and you’ve got no idea.

- Ashley:

Well, that’s scary.

- Talia:

First of all, report them, second of all block them. Yeah, and then do something. And then tell a trusted adult. Make sure you don’t say anything back, or else sometimes it could lead to them finding your location because you replied or something.

- Livvy:

Yeah, and then also it could lead to other things happening with that person. If you replied, like went, ‘Oh, nice’, or something like that, you get end up getting at fault.

There is a ceaselessness to these encounters that can, for some girls, be traumatising; as Ashley acknowledged, the first exposure can be scary. Digital citizenship programmes, relationships, and/or sex and sexuality education do not prepare girls for these encounters. The embedding of postfeminist dispositions positions the girls to believe themselves to be empowered to take on individualised appropriate action; unjustly, they view themselves as naturally obligated to take on this work. Throughout this study, Talia was the only girl to suggest that she would approach an adult. Talia, Livvy, and Ashley were the youngest in this study, which may explain their willingness to approach an adult, as well as their more trusting view of reporting processes. Nevertheless, even these solutions did not prevent Talia from expressing her anxieties about location services, which would enable the sender of the image to track communications to find her home. Continuing the conversation, Livvy signalled her concerns about how the girls can be held culpable if they reply to the sender of the unsolicited image. As we have seen, for some girls, replying can give them a sense that they are taking back power and control from the perpetrators. Ultimately, as seen in other studies, instead of expressing anger about the actions of the perpetrator, the girls in this study addressed the culpability they feel they have in the encounter and the likelihood that the female victim will be blamed for any actions they might take, reflecting the girls’ sense of gendered responsibilisation (see [

24]).