Abstract

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the public were still unaware of the disease and its transmission, and information on susceptibility and severity was not well understood. During this time, stigma of COVID-19 patients had led to some people dying in their homes because they did not want to be seen seeking treatment and getting stigmatized in the process. The study examined stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook and Twitter messages written by youth in Malaysia. A total of 100 messages were collected from the posts of young people in Twitter (n = 66) and Facebook (n = 34) from March 2020 to April 2021 during the early phase of the pandemic. The social media postings, mostly written in Malay, were analyzed for stigma-markers. The results showed that COVID-19 stigma words were mostly related to health (57%), ethnicity (29%), social class (13%), and work (1%). The frequencies of the types of stigma-marker in Facebook comments and tweets are similar. COVID-19 patients were referred to as stupid, irresponsible, and criminals. Racist remarks were also evident in the social media messages. The findings indicate that people who are already victims of the disease are victimized further due to the stigmatization by strangers and people in their social and work circles.

1. Introduction

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the public were still unaware of the disease and its transmission, and information on susceptibility and severity was not well understood. During this time, stigma of COVID-19 patients had led to some people dying in their homes because they did not want to be seen seeking treatment and getting stigmatized in the process. A portion of the brought-in-dead cases were due to COVID-19 infected persons refusing to seek treatment, and stigma has been identified as a contributing factor in Zambia [1,2].

Stigma involves “the process of stereotyping in which the labelled person is linked to undesirable characteristics” [3]. Fear of being stigmatized may cause people to hide their disease, avoid voluntary testing, and refuse to seek for treatment. About a year after the COVID-19 pandemic hit Malaysia, there were 4856 COVID-19-related deaths in the first half of 2021, and in 13.8% of the cases, the patients were brought in dead to the hospital [4]. To mitigate the stigma, the health director-general maintained non-disclosure of the places where the COVID-19 patients were living or working despite pressure from the public because of patient confidentiality; he stated that “the resulting stigma could also be long-lasting” [5]. As an example, a COVID-19 patient who was discharged from Sungai Buloh Hospital said that she was stigmatized by her colleagues, who refused to meet her in person [6]. In India, Sahoo and Patel’s (2021) study shows that social stigma spread due to fake news, lack of awareness and fear of corona infection [7].

As stigma is linked to lack of awareness, the literature was searched to find out the knowledge level of Malaysians towards COVID-19. The scenario presented in academic publications differs vastly from newspaper reports, partly because researchers tend to target highly educated participants who are usually better informed. For example, Alabed et al.’s (2022) respondents comprised 88.5% graduates, and they showed good knowledge of COVID-19 [8]. Most of the 520 respondents were aware that COVID-19 is more fatal than the normal flu, and that infected persons may be asymptomatic. They also knew that immediate medical attention can increase chances of survival, and isolation can reduce the spread of the disease. Another Malaysian study with a smaller proportion of graduates (37% of 1075) found that 88.4% of the participants could understand the technical and medical information on COVID-19 [9]. The study, conducted in March 2020, showed that knowledge of COVID-19 was not significantly linked to gender or household size [9]. Participants below the age of 24, without university education, and with non-healthcare occupations tended to incorrectly believe that COVID-19 is caused by bacteria and can be treated with antibiotics [9]. Mohd Hanafiah and Wan (2020) found that females and participants who filled in the Malay language questionnaire were inclined to attribute greater severity to COVID-19 whereas participants with high school education, non-health related occupations, and small households were inclined to agree that lockdown is an unnecessary measure to control the spread of COVID-19 [9]. On the contrary, Sim and Ting (2021) found that graduates and respondents in the lower income bracket were more likely to believe in the effectiveness of the preventive measures than respondents without a degree and higher-income respondents [10]. In their study involving 230 respondents, 62.2% were graduates. It seems that the more highly educated respondents were overly critical and did not take the government messages of COVID-19 control at face value. Questionnaire results are subject to social desirability bias where participants may give responses to look well-informed.

Qualitative studies making use of interview data were better able to show the lack of knowledge about COVID-19 and aided understanding of stigma attached to having COVID-19. Chew et al. (2021) interviewed 18 Malaysian participants aged 18–65 who had recovered from COVID-19 for at least one month and found that they were labelled and blamed by the people surrounding them including the healthcare providers, neighbors, and staff at the service counters [11]. Their findings showed lack of awareness contributed to stigmatization of COVID-19 patients. Stigmatizing attitudes among healthcare providers is not unusual because Yufika’s (2021) study in Indonesia confirmed that healthcare workers with lower educational levels like nurses were found to have internalized stigma and feared getting infected by patients, compared to doctors who have a higher level of education [12]. There is still much more that needs to be understood about COVID-19-related stigma. WHO (2020) also acknowledges that the fear of a new disease leads to stigma, which can “drive people to hide the illness to avoid discrimination, [and] prevent people from seeking health care immediately”, thereby contributing to the spread of the disease among the people [13].

This paper focusses on the COVID-19 situation in Malaysia. Thus far, studies using questionnaires showed acceptable knowledge of the COVID-19 disease in Malaysia [8,13], but did not provide information on COVID-19-related stigma. It is the interviews [11] and newspaper reports that make known incidences of COVID-19 stigma (e.g., [5,6,8]. Newspaper reports are anecdotal accounts and research findings on COVID-19 stigma are still lacking, which is why there is an inadequate understanding of the discrimination faced by COVID-19 patients. To understand the causes and effects of the COVID-19 disease on individuals, naturally occurring data such as news articles and social media messages are crucial since these are naturally occurring data. For instance, Sahoo and Patel (2021) conducted content analysis of newspapers and magazines published in India and found that COVID-19 patients and even suspected cases are stigmatized by their family and neighbors [7]. In many incidences, these persons were not allowed to enter the house or the neighborhood, and many COVID-19 patients or suspected cases committed suicide [7]. In the United States, Budhwani and Sun (2020) found that the stigmatization of COVID-19 as a “Chinese virus” or a “China virus” increased almost ten-fold after Donald Trump used these phrases on Twitter on 16 March 2020 [14]. This resulted in the stigmatization of people of Chinese descent in the United States. At this point in time, there is still inadequate studies of COVID-19-related stigma in social media messages because previous studies tended to be on perceptions of the COVID-19 disease [15,16]. The study examined stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook and Twitter messages written by youth in Malaysia. The specific objectives of the study were to: (1) identify the types of stigma-markers used to label COVID-19 patients; and (2) compare frequency of stigma-markers in Facebook comments and tweets.

2. Theoretical Framework of the Study

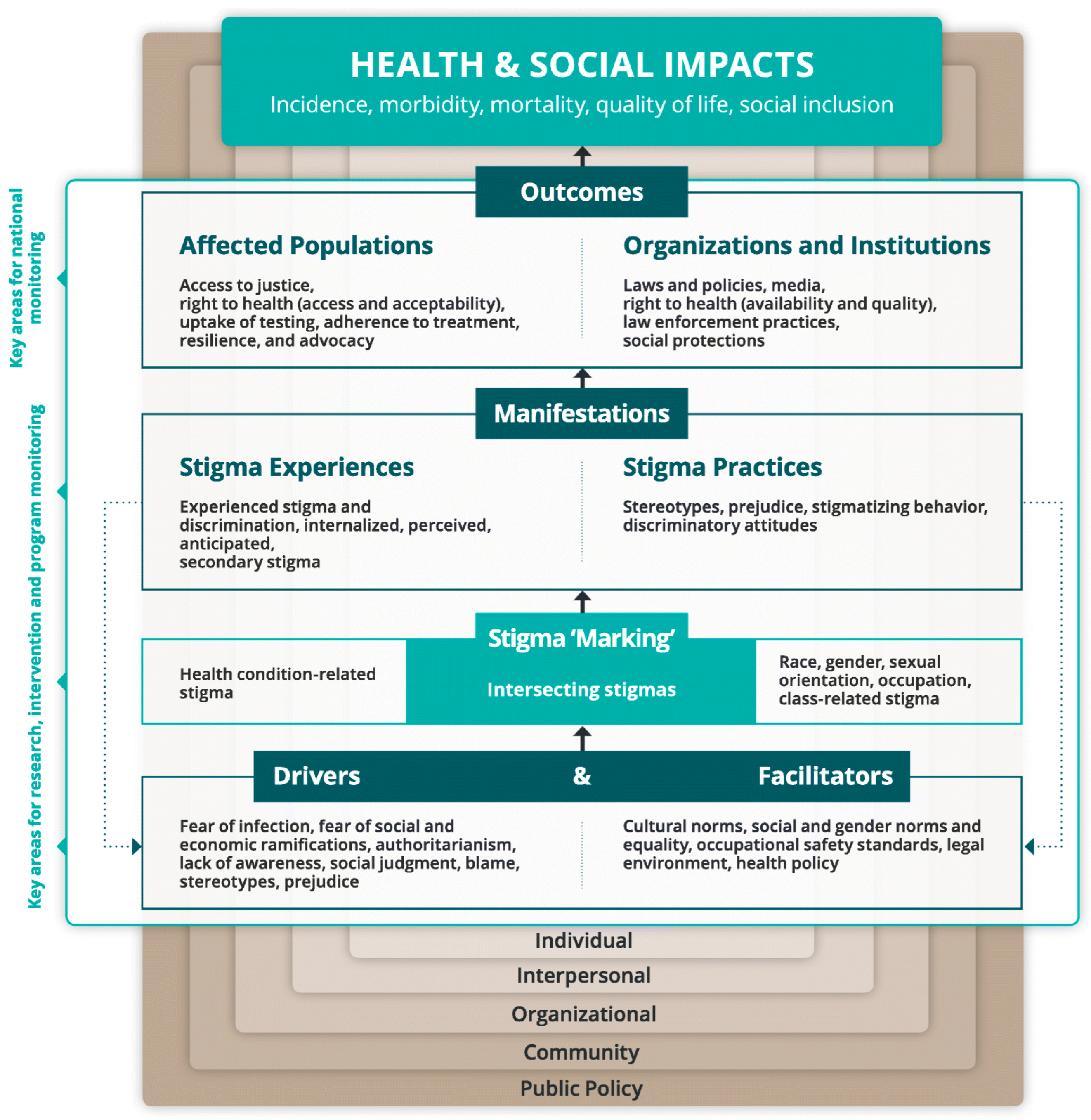

The theoretical framework of the study was taken from Stangl et al.’s (2019) Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework formulated for health-related stigmas, that is, stigma linked to diseases (Figure 1) [17]. For example, Ransing et al. (2020) had used this framework in their study of stigma and discrimination related to an infectious disease outbreak [18]. Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework was not constructed specifically to be used for analysis of social media messages. However, the framework is appropriate for guiding the analysis of health-related stigma in Facebook comments and tweets.

Figure 1.

Stangl et al.’s (2019) Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework [18].

Stangl et al.’s (2019) Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework was used to contextualize stigma-markers, which is conceptualized as resulting from drivers and facilitators [18]. The drivers of stigma arise from fear of infection, lack of awareness, social judgement, blame, stereotypes, and prejudice. Facilitators of stigma-marking are societal norms and health policies. Studies have tended to focus on drivers of stigma, particularly lack of awareness or knowledge of COVID-19 [7,8,9,11]. Stangl et al. (2019) divided stigma-marking into health condition-related stigma and non-health related stigma which encompass race, gender, sexual orientation, occupation, and class-related stigma [18]. In the case of COVID-19, studies have investigated how some of these demographic variables influence knowledge and awareness of the disease but not how these variables become markers of stigma [9,10].

In Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework, the stigma manifestations are studied in terms of stigma experiences (e.g., discrimination; internalized, perceived and anticipated secondary stigma) and stigma practices (stereotypes, prejudice, stigmatizing behavior and discriminatory attitudes) [18]. Yufika (2021) found internalized stigma among healthcare workers in Indonesia, particularly among nurses and paramedical personnel who did not have tertiary education [12].

The stigmatization has unwanted outcomes for the affected populations (e.g., right to health in terms of access and acceptability) and organizations and institutions (e.g., laws and policies; media). This leads to long-term health and social impacts encompassing incidence, morbidity, mortality, quality of life and social inclusion. For example, Sahoo and Patel (2021) found mortality and isolation resulting from people shunning COVID-19 patients in India [7]. The scope of this study does not include stigma manifestations and outcomes because it is restricted to analysis of social media messages. These two components of Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework are relevant to researchers who use questionnaires to study the relationships among constructs of stigma [18].

3. Method of Study

The data analyzed in this study were messages in Twitter and Facebook written by Malaysian youth from 18 March 2020 to 30 April 2021, that is, from the start of the COVID-19 movement restriction to the start of vaccination. The tweets and Facebook comments were posted by the second researcher’s contacts, who were in his age group (early to mid-twenties).

Comments and tweets with elements of stigma were selected for analysis using the search terms in Malay for “pesakit COVID-19” (COVID-19 patients), “bekas pesakit COVID-19” (former COVID-19 patients), “#COVID-19fighter” and “COVID-19Survivor”. The collected messages were screened, and only those pertaining to the COVID-19 patients were selected for analysis. Stigma messages pertaining to the healthcare workers were excluded from the analysis. Altogether 100 messages were identified for analysis (34 Facebook comments; 66 tweets). The messages were not as many as expected because people were careful about expressing their negative views about COVID-19 patients in a public space.

Facebook was selected because it is the most popular social media network in the world for several years already [19]. Facebook is also the most popular social media platform in Malaysia in the year 2020, because 86.06% of social media users use Facebook [20]. Twitter was second in popularity in the year 2020 in Malaysia, accounting for 2.33% of active social media users [20].

In this study, only text was analyzed. Emoji, although a popular form of expression on social media, was excluded. For analysis of social media messages in the present study, only the second part of the framework on signs of stigma is relevant. The other parts of Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework is used to contextualize the results [18]. In the preliminary stage of coding, two researchers identified negative words used to label or describe COVID-19 patients and these were first coded as health and non-health related. However, later the themes that emerged on the non-health related stigma-markers were ethnicity, social class, and occupation. The number of themes were counted and a comparison was made between Facebook comments and tweets. The inter-rater reliability is 96%. The disagreement was over four messages, which were coded as class (religious group) by one researcher and ethnicity by another researcher. The religious group (Muslim) is actually a proxy for ethnicity (Malay) in Malaysia because, based on Article 160 of the Malaysian constitution, a “Malay” is a person who professes the religion of Islam. After discussion, these four messages were coded as ethnicity to take account of the societal norms.

4. Results

The first part of the results section presents the qualitative analysis of Facebook comments and tweets separately. The messages are referred to as Facebook comment 1 to Facebook comment 34, and Tweet 1 to Tweet 66. The second part of the Results section presents a quantitative comparison of the frequency of the different types of stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments and tweets. For ease of comprehension by readers from different language backgrounds, the original tweets in Malay are translated to English in this paper. The original Malay tweets are in Appendix A.

4.1. Facebook Comments with Elements of Stigma

Out of 34 Facebook comments that stigmatize COVID-19 patients, a majority of the stigma-markers were related to health (20 or 58.8%), followed by ethnicity (12 or 35.3%) and social class (2 or 5.9%). The Facebook users labelled the COVID-19 patients as criminals (penjenayah), insane people (orang gila), stupid (bodoh), proud (sombong), traitor (pengkhianat negara), and super-spreader. The italicized words are in Malay.

Table 1 shows examples of Facebook comments on health (total of 20 in the dataset). Since the social media posts selected were on the topic of COVID-19, it is expected that there would be more health-related comments because it concerns the spread of the disease [21]. For example, in Facebook comment 1, the social media user stated that netizens criticized his/her family and were angry with them as if they had committed a big crime. Facebook comment 7 shows that there was a stigma attached to those who had COVID-19 because the public was afraid to catch the disease from them (see also Facebook comment 12). Facebook comment 17 was a response to this sentiment and appealed to netizens not to isolate them as they were not criminals.

Table 1.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments on health (N = 20).

Table 2 shows ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia from 13 March 2020 to 8 July 2020, there were several clusters of cases linked to the Tabligh Jamaat religious conference in Kuala Lumpur, which is why ethnicity-related stigma was strong at the time of the data collection. The religious conference (27 February to 1 March 2020) was termed as a COVID-19 super-spreader event in the newspapers. By 19 May 2020, the Malaysian Director-General of Health Noor Hisham Abdullah confirmed that 48% of the country’s COVID-19 cases (3347) had been linked to the Kuala Lumpur Tablighi Jamaat cluster [22]. Facebook comments 23–26 were comments on the Tabligh event. The Facebook users openly criticized the Muslims for being so stupid to spread the disease. This is an example of hate messages towards certain communities that are blatantly expressed in the social media.

Table 2.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments (N = 12).

On the surface, Muslims were criticized but underlying this, the Malay community was also the target. This is because by law, all Malays are Muslims in Malaysia, and Islam is the official religion. Based on the 2020 Population and Housing Census, 63.5% of the population in Malaysia are Muslim. The population of Muslims who are not Malays is small but no information is available. The close interconnection of the Muslim faith and Malay ethnicity is an example of intersecting stigma mentioned in Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework on health stigma and discrimination [18].

Other ethnic groups were not spared in the stigmatization, and the targets were those with immigrant origins. Facebook comment 22 targeted the Chinese because the virus was said to originate from China. Facebook comments 26–29 targeted the Indian because of the Sivagangga case. A Malaysian of Indian descent who owned a nasi kandar restaurant in Kedah returned from India. He did not observe home quarantine orders, spread COVID-19 to his family, workers, and customers, and was linked to the first case in Penang [23]. The hitherto subdued views on immigrants surfaced, whereby a Facebook user said that Sivagangga should go back to India. Even though Indians have settled in Malaysia since the 18th century, there are still residue views of them as immigrants. “Organized Indian immigration to Malaysian peninsula began with the establishment of the East India Company stationed in Penang in 1786” [24]. When problems like the spread of COVID-19 happens, they are asked to go home although they are Malaysian citizens. In fact, they are born in Malaysia and it was their great grandparents and earlier generations who had migrated from India. For example, Facebook comment 28 criticised the nasi kandar restaurant owner for being stupid (“dia ni otak tarak”, translated to “he has cockroach brains”) and Facebook comments 29–32 urged the unmentioned authorities to chase him back to his home country. These messages are racist, to say the least.

Finally, foreigners in general were stigmatized and an example is Facebook comment 21 where “terminal” is mentioned. The airport terminal is the main entry point into Malaysia. Most foreigners fly into Malaysia, rather than arrive by ship, train or bus. The 12 Facebook messages showed that the netizens were afraid of foreigners who brought the disease into Malaysia. The public’s attention is drawn to foreigners, partly because in the daily press conferences conducted by the health director general, there are specific numbers of COVID-19 cases for illegal foreigners (referred to as Pendatang Tanpa Izin). This focus on foreigners is not limited to Malaysia because neighbouring countries like Singapore also do similar daily reports. Foreign labourers are then stigmatized as a result.

Table 3 shows stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in Facebook comments. Facebook comment 33 targeted the rich who could afford to travel overseas whereas Facebook 34 comment targeted the older people who died due to COVID-19. The rich are viewed differently because of their social status. Facebook comment 33 basically sent the message “you asked for it” because the rich still chose to travel during the COVID-19 pandemic and so it is not surprising that they catch the virus and bring it back to Malaysia and pass to other Malaysians. The rich are portrayed as committing an irresponsible act. As for Facebook comment 34, it is a farewell message to a deceased person, but this is not obvious at first glance. The older age group is more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, hence, are stigmatized.

Table 3.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in Facebook comments (N = 2).

4.2. Stigmatization in Tweets

Altogether 66 tweets were analysed, and the results showed that the COVID-19 stigma words were mostly related to health (37 or 56.1%), ethnicity (17 or 25.7%), social class (11 or 16.7%), and work (1 or 1.5%). The Twitter users showed their contempt for COVID-19 patients using intensification strategies. They labelled the COVID-19 patients as selfish, stupid like cows (bodoh macam lembu; bangang in Sarawak Malay dialect), dumb, illegitimate child (anak haram), super-spreader, criminals who should be prosecuted, disgraceful scum, affluent cluster (kluster kayangan), irresponsible, pig (babi), and infidels (kafir laknatullah).

The COVID-19 stigma-markers in the health category are linked to COVID-19 patients being possibly infectious. The Twitter users had no reservations in expressing their contempt for these individuals. Tweet 1 expressed the anger of the Twitter user who labelled COVID-19 patients as selfish because they knew they were positive and yet lied about it (see also Tweet 15). In other words, they did not quarantine themselves but moved among other people and spread the disease. If anything, the public service announcements on COVID-19 has created the awareness that people can carry the coronavirus and infect others, which is why in Tweet 2, the Twitter user said that he/she was afraid to get close to their housemate for fear of catching the disease from him/her. Tweets 3–7 were about the woman who was working in Johor and brought the virus to Sarawak when she came back to Sibu to attend her father’s funeral in the longhouse just before Christmas 2020. Tweets 5–7 even cursed her to die with her father. This shows the extent of the public’s rage with COVID-19 patients who spread the disease to other people. The rage is particularly high when the area was clean prior to the appearance of the first case in their area. The public looked forward to a lessening of movement control and travel restrictions and when people kept spreading the disease, it prolonged the lockdown.

COVID-19 patients were also labelled as super-spreaders and this is definitely a health-related stigma-marker. Tweets 8–19 show the Facebook users’ concern that they spread the disease to many people and cause a cluster to develop. Apparently, the Twitter users knew who exactly Patient 136 was and said that they should have succumbed to the disease in Korea. The Ministry of Health Malaysia kept his identity anonymous but Patient 136 from Negeri Sembilan himself tweeted his own explanation [25]. He explained that he did not have any COVID-19 symptoms for the first ten days after returning from Korea and had gone to several places and mixed with many people before symptoms showed up on Day 11. At that point in time, the quarantine period of Malaysians returning from other countries was 14 days, so Patient 136 had violated the stay-home orders. This is why netizens were angry with Patient 136 and wished he could get Stage 5 of COVID-19 (Facebook 19) and asserted that he should be prosecuted (Facebook 11). Stage 5 is the critical stage, whereby patients need non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support and they may have organ failure.

Table 4 shows tweets stigmatizing COVID-19 patients from certain social classes. According to Durante and Fiske (2017), the existence of stereotypes on social class arises when there is injustice in societal life [26]. The Tweets stigmatized the Tabligh participants, older people, and the “kayangan cluster” (literally translated as “heavenly cluster”, meaning “affluent cluster”). The reason for stigmatizing Tabligh participants has been explained in the previous section on Facebook comments. The stigmatization of older people was brought up but here there are more details (Tweet 45–48). The older people who get COVID-19 are branded as stupid for causing trouble to others, and ought to be shot dead.

Table 4.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in tweets (N = 11).

If in Facebook comments, the social class who can afford overseas travel are blamed for bringing the virus back to Malaysia, here in tweets, the “kluster kayangan” (affluent cluster) are condemned. Tweets 38–44 said that the rich went overseas and looked for the virus. Tweet 40 cursed them for seven generations. It seems that social media users unleashed their emotions more freely in tweets, compared to Facebook comments. The kayangan cluster is a term used to refer to people who are proud and expect first class treatment [27]. The rich people were labelled as “biadap” (rude) and thought little of causing trouble to others.

Table 5 shows ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in tweets, which makes racism very explicit. References to the Tabligh cluster in Tweets 49–52, 58 and 60 targeted Muslims on the surface, but in fact, the target was Malays in the Malaysian context, as explained in the section on Facebook comments. In the tweets, Malays were branded as irresponsible and stupid (“bodoh”). Tweets 53 and 56 targeted the Chinese. The Chinese were also branded as stupid (Tweet 59). Tweet 53 said, “Your people ate the satan bat”, referring to the original place of the Chinese in China, and this sentiment was shared by the Twitter user in Tweet 57 (#ChineseVirus). The people in Malaysia do not forget that the Chinese were immigrants. The Indians were also not left alone. Tweets 62–64 referred to the Indians as “keling”, which is a derogatory term. Here, the Sivagangga cluster was not mentioned but the details pointed to the restaurant owner (Tweet 64: Disebabkan si keling yg balik dari India tak kuarantin di rumah). The word “keling” originates from the word Kalinga which is a famous empire in the India continent [28]. However, in the Malaysian text, the word “keling” is not used with the glamour. The tweets show use of coarse language to talk about other ethnic groups who spread COVID-19. Ethnicity-related stigma happens when one ethnic group feel that they are superior to other groups [29]. These comments, if aired on conventional mass media platforms, may incite racial riots but seem to be forgivable in the social media context.

Table 5.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in tweets (N = 17).

Table 6 shows Tweet 66 stigmatizing COVID-19 patients from certain occupations, namely, the medical profession and the police. Frontliners in these occupations are often in direct contact with COVID-19 patients and may be asymptomatic. They may then carry the virus home and infect their family.

Table 6.

Tweet stigmatizing COVID-19 patients from certain occupations (N = 1).

To sum up, according to Durante and Fiske (2017), the existence of stereotypes on social class arises when there is injustice in societal life [26]. The Tweets stigmatized the Tabligh participants, older people, the “kayangan” cluster, and frontliners. There was only one tweet stigmatizing medical personnel as carriers of the COVID-19 virus but studies elsewhere have shown that they are the target.

4.3. Frequency of Different Types of Stigma-Marking of COVID-19 Patients in Facebook Comments and Tweets

Table 7 shows the frequency and percentage of types of stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments and Tweets (N = 100). The percentages of different types of stigma-marker are similar in the two social media platforms for health (Facebook, 58.8%; Twitter, 56.1%) and for occupation (Facebook, 0%; Twitter, 1.5%). However, Facebook had far more stigma-markers related to ethnicity (35.3%) than social class (5.9%). The difference was not as great for Twitter although there were also more ethnicity-related markers (25.7%) than social class-related stigma-markers (16.7%). As explained in the previous sections, the intensity of the sentiments expressed is much higher in the tweets than in Facebook comments. Expressions like “far more stigma markers” or “higher” are included for descriptive purposes only.

Table 7.

Frequency and percentage of types of stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments and tweets (N = 100).

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between social media platform and types of stigma-marker. The relation between these variables was not significant, χ2 (3, N = 100) = 3.25, p = 0.35. The types of stigma-markers in Facebook comments and tweets were similar. The effect size of the χ2 test was determined using Cramer’s V. As the V is close to 0, the magnitude of the observed effect is small.

5. Discussion

The analysis of stigma-marking in Facebook comments and tweets posted by Malaysian netizens in their early twenties yielded key findings on the types of stigma-markers and the intensity of stigmatization. Firstly, as COVID-19 pandemic is due to a disease, it is expected that the main stigma-marker is health-related because the netizens are afraid of getting infected by the COVID-positive patients. The stigmatization is due to the health status of the COVID-19 patients, that is, they are carrying the virus. In India too, people who have got COVID-19 were perceived as active spreaders of the disease, and the society accused them of being proud and self-centered [30]. In addition, they were viewed as weak and irresponsible, and the society unleashed their anger on the COVID-19 patients. The health-related stigma-marker suffered by COVID-19 patients is similar to the stigmatization experienced by army personnel suffering from mental issues, and they were viewed as disabled, irresponsible, and a threat to the local community [31]. According to Stangl et al.’s (2019) framework, the driver for health-related COVID-19 stigma-marking is fear of infection, which in turn arises from lack of awareness [18]. For AIDS/HIV, low education levels and poor knowledge of risk factors, transmission, prevention and treatment lead to stigmatization, to the extent that it is hard to get people to manage the funeral of AIDS/HIV patients [32].

However, the next highly ranked stigma-marker is ethnicity related, and this finding needs to be discussed in the context of Malaysia. Malaysians are defined by their ethnic group possibly more than by any other social marker. Ethnicity (bangsa in Malay) is “the most important point of reference right down to everyday conversations in which the assertion of one’s own and the other’s bangsa-background is part and parcel of getting to know each other” [33]. In Malaysia, even membership forms for goods and services (like Guardian and Watsons stores) require ethnic background to be stated. The results of the present study show that Malay, Chinese, and Indian are all stigmatized in some ways. There was a great deal of name-calling in the Facebook comments and tweets. Malaysians from various ethnic groups have been trying to live peaceably with one another and confine racist remarks to conversations with trusted people, usually of the same ethnic group. However, the social media discussions on COVID-19 transmission seem to bring the racist sentiments to the surface, and it disrupts the surface appearance of harmony in ethnic relations.

Elsewhere in the world, it is the Chinese who are stigmatized. For example, the Chinese and Asians in Italy were stigmatized because the origin of the COVID-19 virus was traced to Wuhan, China in December 2020 [34]. The stigmatization is so bad that Asians were not allowed to enter business premises and have even been physically assaulted in Vincenza [34]. The anti-Asian sentiments are captured by the terms “Chinesevirus” and “Chinese syndrome” to COVID-19 [34]. The term “Chinesevirus” was first used by Donald Trump, the former president of the United States, but the impact is felt in other countries. Indian citizens of Chinese descent living in Northeast India have been the target of racism and discrimination, to the extent that they have been regarded as foreigners in their own country [30]. The stigma of being or looking like a Chinese affected East and Southeast Asian students at a Jordanian university, and they experienced cyberbullying in the form of social stigma and discrimination [35]. In Malaysian Twitter space, based on the present study, there was one reference to COVID-19 being a Chinese virus (“Negara tok nenek korang tu”, meaning “that is your ancestor’s country”).

In the present study, most of the references in the social media messages were to Malays (because of the religious Tabligh cluster that sparked the first wave of the pandemic in Malaysia) and the Indians (because of the Sivaganggar restaurant cluster). The Facebook comments and tweets also talked about two more clusters linked to an Iban from Sarawak (“woman who came back from Johor”) and a Malay young man (“Patient 136”) but no ethnicity references were used by the netizens. In comparison to stigma-marking based on health and ethnicity, other markers based on class and occupation were not as common among the Malaysian netizens.

Secondly, the intensity of stigmatization in Facebook messages was stronger than in tweets. Comparative expressions are included for descriptive purposes only, and not based on inferential statistical tests. The resounding theme of the social media messages on COVID-19 patients is “Stupid, you cause trouble for others!” “Stupid” is the main characterisation of COVID-19 patients, said in English along with “dumb” (but not frequently used), Malay “bodoh” and Sarawak Malay Dialect (“bangang”). For Malaysians, the adjective “stupid” is a polite code for a number of unspeakable descriptors, and it is said with intense emotion when used for scolding other people. In newspapers, Malaysians have been called “stupid”. For example, “Do we ‘stupid Malaysians’ prove him right or wrong?” [36]. There are many other news headlines, where even ministers were called “stupid”. Another example is “M’sian academics called out for saying ‘stupid’ things” [37]. In a way, “stupid” is an acceptable word to use for insulting others in public. The Facebook comments collected in the present study only called the COVID-19 patients stupid for being reckless to get the disease and to pass it to others but in the tweets, they were described as “stupid like cows” (“bodoh macam lembu”). Being called “stupid” is mild, compared to being called a “criminal” (penjenayah) or “traitor” (pengkhianat negara) for flouting quarantine orders. This is because Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 (Akta Pencegahan dan Pengawalan Penyakit Berjangkit 1988) can be used to charge individuals who flout Standard Operation Procedures (SOPs) for the control of COVID-19 [38]. The compound fine for individuals is RM1000 and for businesses, it is RM10,000. There were calls for the fines to be increased, but it was not passed by the parliament. In the Facebook comments and tweets analyzed in the present study, there were voices of COVID-19 patients, and others in support of them, appealing to netizens not to call them criminals and shun them. It is interesting that this is the stigma-marker that was singled out by the COVID-19 patients to respond to.

Further analysis revealed that the stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients is more intense in tweets than in Facebook comments, based on the qualitative language analysis. As an example, in Facebook comments, COVID-19 patients have been called “orang gila” (insane) and “sombong” (proud) but in tweets, they were called “anak haram” (illegitimate child), “disgraceful scum”, “kluster kayangan” (affluent cluster), “irresponsible”, “babi” (pig) and “kafir laknatullah” (infidels). The last two stigma-markers in this list have a religious context. In Islam, a pig is a religiously dirty animal and Muslims do not eat pork. In the Malay language, “babi” means “pig” and calling someone “babi” is an insult, and Malaysians have even made fun of a K-pop Star for using Babi as her stage name and Albanian Singer Dua Lipa for using the Albanian word “babi” for “father” [39]. In Malaysia, “babi” is “a top tier insult used by almost everyone who thinks it’s the right thing to say during an argument” [40]. As for “kafir laknatullah” (infidels), it means “someone who does not have the same religious beliefs as the person speaking” [41], and is often used by Muslims in Malaysia to refer to non-Muslims. In fact, if some of these insult words are used in face-to-face communication, they can lead to racial riots.

The language is stronger, and more emotive in tweets than in Facebook comments. This is possibly due to the difference in the profiles of the users and the purpose of the two social media platforms. “People make connections on Facebook with friends, family members, and other people that they care to keep in touch with. Twitter allows people to follow important topics, people, and conversations that are relevant or interesting to them. It’s a much more detached connection” [42]. When the netizens know one another like in Facebook, they are inclined to be more careful about their speech because they may get backlash from people in their social network whom they know and meet in person. However, in Twitter, strangers discuss issues and events. Based on their interviews with Indonesian teenagers, Juwita, Effendi, and Pandin (n.d.) concluded that the anonymity that is allowed in Twitter leads to oversharing and free expression of feelings [43]. The teenagers in their study usually have two accounts: one real life, and another anonymous. However, the inclination to insult may not necessarily be more in anonymous Twitter accounts. “While 32 per cent of tweets from anonymous accounts were classed as angry, so too were 30 per cent of tweets from accounts with full names” [44]. Another probable factor accounting for the intensity of COVID-19 stigma-markers in tweets is the age group of the social media users. Naim (2022) reported over 51.1% of the Facebooks users in Malaysia were young (17.6% aged 18–24 and 33.5% aged 25–34) and 56% were male. Similar statistics on Malaysia were not available for Twitter users [45]. However, global statistics show that as of April 2021, about 62.5% were young (24% below 24 and 38.5% aged 25–34) [46]. It is probably because young people are more open in their views compared to the older generation in the context of Malaysia. More than one in four teenagers say social media is an important avenue for them to express themselves creatively [47]. The older people are still reserved in their views, particularly in public spaces but this needs to be investigated in future studies.

6. Conclusions

The study on stigma-marking of COVID-19 patients in Facebook and Twitter messages written by Malaysian youth showed that the main stigma-marker is health-related, followed by ethnicity, social class, and occupation. Typical stigma-markers for these four categories are super-spreader, Tabligh/Sivagangga, “kayangan” (affluent) cluster, and nurse/doctor/police/frontliner, respectively.

The present study has indicated that Twitter messages have greater potential to bring researchers closer to understanding the “real” feelings and attitudes towards issues and events. It is often difficult to recruit individuals to participate in studies on stigma if the purpose of the research is explicitly made known. However, social media communication containing naturally occurring interactions provides authentic data for researchers in media studies and stigma studies. This is because the views expressed in social media platforms are not opinions manufactured for the benefit of researchers. These findings are useful for policy makers such as government agencies related to social and community development when formulating policies and strategies on societal harmony. In Malaysia, textbooks for History and Moral Education teach the value of racial harmony. In universities, there is a compulsory subject (Ethnic Relations) which also has the agenda to teach unity among ethnic groups. These are the avenues for teaching the young minds about freedom of speech, in the sense that they should not be rash in articulating their opinions in social media until it infringes on the right of other ethnic and social groups to exist as Malaysians. Based on the findings of this study, it seems that the young people do not realize that their views in Facebook and Twitter stay permanently on record. They need to be educated on the permanence of written communication, and that words uttered in the heat of the moment may take on other meanings with the passage of time.

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, the data in the present study were restricted to Facebook comments and tweets on COVID-19 collected from 18 March 2020 to 30 April 2021 among Malaysians. Secondly, as the focus was on COVID-19 patients, stigmatization of healthcare workers was not captured in the present study. This angle was not explored, partly because previous research on other diseases had shown stigmatization of healthcare workers like in the case of Ebola [32]. In India, during the COVID-19 pandemic, police and doctors were so stigmatized by the local communities that they were forced to sleep in the staff room and use toilets in their workplace, and even taxi drivers did not want to provide services to them for fear of catching the infection from them [29]. Thirdly, the social impact of COVID-19 stigmatization was not investigated in the present study. An area for future research is the stigma experiences and practices which result from the stigma-marking because these are manifestations of the stigma-marking in the form of behaviors. The Facebook comments and tweets examined in the present study, particularly the voice of COVID-19 patients, provide an inkling of their stigma experiences but this aspect needs to be investigated in greater depth to understand public prejudice, stigmatizing behavior, and discriminatory attitudes for infectious diseases. In the context of COVID-19, the public’s behavior of isolating COVID-19 patients may be good for stopping transmission of the disease, but it has negative consequences on the patients’ quality of life and social inclusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.T.; methodology, S.-H.T. and M.H.S.; formal analysis, M.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.S.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.T.; supervision, S.-H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UNIMAS Dana Pelajar PhD, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, F09/(DPP49)/1277/2015(24).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not involve humans; only publicly available texts were analysed.

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not involve humans; only texts were analysed.

Data Availability Statement

Data are reported in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Original Tweets in Malay

Table A1.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments on health (N = 20).

Table A1.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments on health (N = 20).

| Facebook Comment | |

|---|---|

| Facebook 1 | Netizen kecam saya, hina keluarga saya. Mereka marah seolah kami dah buat satu jenayah besar. |

| Facebook 7 | Kepada orang-orang diluar sana yang takut sangat nak jumpa bekas pesakit COVID-19. takut sangat jangkit. |

| Facebook 12 | Masa mula kami d sahkn positif COVID xda siapa dtg dekat bergaul… slepas sembuh dri COVID xda jga yg dtg bgaul dgn kmi but after few days kwn jiran dtg brtnyakan khbar. |

| Facebook 13 | Kebanggaan wargaSibu super spreader Johor tak rasa bersalah lagi tu… |

| Facebook 14 | Saya harap Harilast nanti abg mati. |

| Facebook 17 | Jangan pulaukan pesakit COVID! Kami bukan penjenayah…! |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

Table A2.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments (N = 12).

Table A2.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in Facebook comments (N = 12).

| Facebook Comment | |

|---|---|

| Facebook 21 | Ak duk terminal ni pon seram tgk puak warga asing ni rentas. |

| Facebook 22 | COVID-19 asal mana? China kan? Hah bising kenapa? China lah punca. Negara tok nenek korang tu. Pergi salahkan negara sendiri. |

| Facebook 26 | Semua melayu punya pasal Malaysia kena COVID dan banyak mati!PKP pun sebab melayu tarak guna.Semua pasal TABLIGH!Lagi banyak akan mati. |

| Facebook 28 | Mampoih la sivangga ka belanga ka apa ka, yg penting dia ni otak tarak, sop x leh ikut hntaq dia balik dok kg ja, 1 kubang pasu susah pasai dia ni. |

| Facebook 32 | Sita kedai… ban drpd berniaga… hantar balik negara asal senang. |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

Table A3.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in Facebook comments (N = 2).

Table A3.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in Facebook comments (N = 2).

| Facebook Comment | |

|---|---|

| Facebook 33 | Tapi, pada yang pergioversea di saat wabak COVID-19dah start kat negara luar, bawak balik pula virus tu ke Malaysia. Itu memang saja minta dijangkiti. |

| Facebook 34 | Selamat jalanpakcik. |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

Table A4.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in tweets (N = 11).

Table A4.

Examples of stigmatization of COVID-19 patients from certain social classes in tweets (N = 11).

| Tweet | |

|---|---|

| Twitter 40 | Kluster kayanganbalik obersee piholidaytu klo positif mmg aku sumpah 7 keturunan bodoh mcm lembu. |

| Twitter 45 | Bodo piang org tua2ni memang kadang dia punya bodo tu tahap tak tau nak kata apa dah. |

| Twitter 46 | Mati jelah pakcik, menyusahkan orang je |

| Twitter 47 | Tembak matijerlah org mcmnie… |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

Table A5.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in tweets (N = 17).

Table A5.

Examples of ethnicity-related stigmatization of COVID-19 patients in tweets (N = 17).

| Tweet | |

|---|---|

| Twitter 49 | Geng tabligh yang kena jangkitlepastu sebar kat seluruh Malaysia |

| Twitter 50 | Well done Malaysia, especially to the ppl who attended the religious meeting in Sri Petaling and insisted not to be tested because his god can protect him. |

| Twitter 53 | Selama ni aku x judge pun orang kau sejak COVID-19 ada, orang kau yang makan kelawar cetan!!!! |

| Twitter 54 | Tiba tiba muncul pendatang asing dari indon bawa balik penyakit balik. |

| Twitter 56 | Dua2 lanjio melayu ke cina ke semua babi. |

| Twitter 57 | #ChineseVirus |

| Twitter 59 | Bodoh punya cina kafir laknatullah. |

| Twitter 60 | Sejak ada COVID-19 ni baru aku sedar yang melayu memang bodoh. |

| Twitter 63 | Kepala buto la keling ni xsedar diri dh la blk sini kerajaan tanggung flight hg bg mkn hg tempat tinggal dok menyalak lagi. |

| Twitter 64 | Disebabkan si keling yg balik dari India tak kuarantin di rumah |

| Twitter 65 | Lpas sy citer ade close cntac dgn yg kna kuartin, terus nurse mlyu lari. Lpastu tgok dr jauh je. Lalu jeling2. Mcm hina sgt. Bodoh ade mlyu mcm tu. |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

Table A6.

Tweet stigmatising COVID-19 patients from certain occupations (N = 1).

Table A6.

Tweet stigmatising COVID-19 patients from certain occupations (N = 1).

| Tweet | |

|---|---|

| Twitter 66 | Adakahnurse, doktor, polis dan frontlinersemua ditempatkan di sesuatu tempat semasa merrka bertugas? Jika mereka pulang ke rumah masing2, adakah keberangkalian ahli keluarga dijangkiti sekiranya mereka positif COVID. |

(Bolding shows words stigmatizing COVID-19 patients).

References

- Chileshe, M.; Mulenga, D.; Mfune, R.L.; Nyirenda, T.H.; Mwanza, J.; Mukanga, B.; Daka, V. Increased number of brought-in-dead cases with COVID-19: Is it due to poor health-seeking behaviour among the Zambian population? Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mwale, Z. Stigma, Fear Linked to COVID-19 Spike. Zambia Daily Mail Limited. Available online: http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/stigma-fear-linked-to-covid-19-spike/ (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet 2006, 367, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, T. Malaysia Sees Exponential riSe in Brought-in-Dead COVID-19 Cases. New Straits Time. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/07/704592/malaysia-sees-exponential-rise-brought-dead-covid-19-cases (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Koh, J.L. Stigma and Confidentiality—Why COVID-19 Locations Are Not Disclosed. Malaysiakini. Available online: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/514087 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Wahid, R. Ex-Patient: Social Stigma More Painful Than COVID-19. Malaysiakini. Available online: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/557795 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Sahoo, B.P.; Patel, A.B. Social stigma in time of COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from India. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 4, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabed, A.A.A.; Elengoe, A.; Anandan, E.S.; Almahdi, A.Y. Recent perspectives and awareness on transmission, clinical manifestation, quarantine measures, prevention and treatment of COVID-19 among people living in Malaysia in 2020. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Hanafiah, K.; Chang, D.W. Public Knowledge, Perception and Communication Behavior Surrounding COVID-19 in Malaysia. 2020. Researchgate. Net. Available online: https://advance.sagepub.com/articles/preprint/Public_knowledge_perception_and_communication_behavior_surrounding_COVID-19_in_Malaysia/12102816 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Sim, E.U.H.; Ting, S.H. Public Knowledge and Perception of COVID-19 and Its Preventive Measures. In COVID-19, Education, and Literacy in Malaysia; Pandian, A., Kaur, S., Cheong, H.F., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, C.C.; Lim, X.J.; Chang, C.T.; Rajan, P.; Nasir, N.; Low, W.Y. Experiences of social stigma among patients tested positive for COVID-19 and their family members: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yufika, A.; Pratama, R.; Anwar, S.; Winardi, W.; Librianty, N.; Prashanti, N.A.P.; Sari, T.N.W.; Utomo, P.S.; Dwiamelia, T.; Natha, P.P.C.; et al. Stigma associated with COVID-19 among health care workers in Indonesia. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 16, 1942–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Social Stigma Associated with COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Budhwani, H.; Sun, R. Creating COVID-19 stigma by referencing the novel coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” on Twitter: Quantitative analysis of social media data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoy, D.; Godinic, D.; Tong, Q.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A.; Kurpayanidi, K. Impact of social media, Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM) on the intention to stay at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoy, D.; Tirasawasdichai, T.; Kurpayanidi, K.I. Role of social media in shaping public risk perception during COVID-19 pandemic: A theoretical review. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2021, 7, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransing, R.; Ramalho, R.; de Filippis, R.; Ojeahere, M.I.; Karaliuniene, R.; Orsolini, L.; da Costa, M.P.; Ullah, I.; Grandinetti, P.; Bytyçi, D.G.; et al. Infectious disease outbreak related stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Drivers, facilitators, manifestations, and outcomes across the world. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; Van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barré, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S. Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of January 2022, Ranked by Number of Monthly Active Users (in Millions). 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/#:~:text=Global%20social%20networks%20ranked%20by%20number%20of%20users%202022&text=Market%20leader%20Facebook%20was%20the,2.89%20billion%20monthly%20active%20users (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- StatCounter Global Stats. Social Media Stats Malaysia. 2020. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/malaysia/2020 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Van Brakel, W.H. Measuring health-related stigma. A literature review. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Sun Daily. 48% of Nation’s COVID-19 Cases Linked to Sri Petaling Tabligh Event. Available online: https://www.thesundaily.my/local/48-of-nation-s-covid-19-cases-linked-to-sri-petaling-tabligh-event-HM2428393 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Straits Time. Sivagangga COVID-19 Cluster Spreads Out of Kedah in Malaysia. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/sivagangga-covid-19-cluster-spreads-out-of-kedah-in-malaysia-super-spreader.Tweets (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- High Commission of India. PIO Community. 2020. Available online: https://hcikl.gov.in/Exlinks?id=eyJpdiI6Ing0Y3dVbUJheVJiM0VrNmMycXBYNFE9PSIsInZhbHVlIjoiVDFwVjNGYm5rYkNwRGFcL1c5WnJiakE9PSIsIm1hYyI6ImQ5N2M0YTVjYzBiYTI4NDkxYzRkYjg3ZjNiNGZhNTQ1OTBlYzU0ZTgyOTdjMDUzZGU2MTUwN2YyMGM3MGRlNzYifQ==#:~:text=Organized%20Indian%20immigration%20to%20Malaysian,%2C%20Sindhis%2C%20Gujaratis%20and%20others (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Atan, A. Satu Malaysia Sengsara, Netizen Kecam Pesakit COVID-19 Ke-136 ‘Kuat Merayap’. Available online: https://malaysiadateline.com/satu-malaysia-sengsara-netizen-kecam-pesakit-covid-19-ke-136-kuat-merayap/ (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Durante, F.; Fiske, S.T. How social-class stereotypes maintain inequality. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 18, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matore, M.M.E.E. Pelajar ‘Rosak’ Jika Amal Sikap Kluster Kayangan. Berita Harian. 2020. Available online: https://www.bharian.com.my/rencana/minda-pembaca/2020/09/731433/pelajar-rosak-jika-amal-sikap-kluster-kayangan (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Periaswamy, N. Ada Apa Dengan “Keling”? Free Malaysia Today (FMT). 2018. Available online: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/2018/04/10/ada-apa-dengan-keling/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.L.; Niemann, Y.F.; Snider, K. Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in responding to distinctiveness and discrimination on campus: Stigma and common group identity. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, D.; Singh, T.; Verma, S.K.; Sharad, S. Stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 577018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Held, P.; Owens, G.P. Stigmas and attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment in a sample of veterans and active duty service members. Traumatology 2013, 19, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, M.; Giesecke, J. Ebola and healthcare worker stigma. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, F. Ethnicization and Identity Construction in Malaysia; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, S.; Jaramillo, E.; Mangioni, D.; Bandera, A.; Gori, A.; Raviglione, M.C. Stigma at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1450–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsawalqa, R.O. Cyberbullying, social stigma, and self-esteem: The impact of COVID-19 on students from East and Southeast Asia at the University of Jordan. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovrenciear, J.D. Do We ‘Stupid Malaysians’ Prove Him Right or Wrong? Malaysiakini. Available online: https://www.malaysiakini.com/letters/282781 (accessed on 8 December 2014).

- Hakim, A. M’sian Academics Called Out for Saying ‘Stupid’ Things. The Rakyat Post. Available online: https://www.therakyatpost.com/news/malaysia/2019/10/14/msian-academics-called-out-for-saying-stupid-things/ (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Undang-Undang Malaysia: Akta 342. 2020. Available online: https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/faqsop/akta-342/Draf_Muktamad_Akta_342.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Malaysians Bully Kpop Star so Young Due to Her Stage Name. Available online: https://www.thesundaily.my/spotlight/malaysians-bully-kpop-star-so-young-due-to-her-stage-name-MK2509349 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Urban Dictionary (n.d.). Babi. Available online: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Babi (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Cambridge Dictionary. Infidels. 2002. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/infidel (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Visualscope. What is the Difference between Twitter and Facebook? 2002. Available online: https://www.visualscope.com/twitfb.html (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Juwita, E.T.; Effendi, A.Z.; Pandin, M.G.R. The Effect of Anonymity on Twitter towards Its Users Based on Derek Parfit’s Personal Identity Theory. n.d. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=The+effect+of+anonymity+on+Twitter+towards+its+users+based+on+Derek+Parfit%27s+Personal+Identity+Theory&rlz=1C1GCEA_enMY963MY963&oq=The+effect+of+anonymity+on+Twitter+towards+its+users+based+on+Derek+Parfit%27s+Personal+Identity+Theory&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i60.475j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Van der Merwe, B. Are Anonymous Accounts Responsible for Most Online Abuse? The New Statesman UK Edition. Available online: https://www.newstatesman.com/social-media/2021/10/are-anonymous-accounts-responsible-for-most-online-abuse (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Naim, A. Malaysia Facebook Users Statistics 2022. Available online: https://www.monocal.com/guide/malaysia-facebook-users-statistics/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Dixon, S. Twitter: Distribution of Global Audiences 2021, by Age Group. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/490591/twitter-users-malaysia/ (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Knorr, C. New Report: Most Teens Say Social Media Makes Them Feel Better, Not Worse, about Themselves. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2018/09/13/new-report-most-teens-say-social-media-makes-them-feel-better-not-worse-about-themselves/ (accessed on 13 September 2018).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).