Abstract

In an unprecedented scenario, much of the research and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which focused on young people, found themselves suspended. (1) Background: The goals of this project were to investigate (Study 1) social participation and positive development among young people in Cascais, Portugal, and to investigate (Study 2-a case study) the implementation of a program promoting active citizenship, social participation, and social entrepreneurship. At the same time, it was intended to constitute a resource and strategy to diminish the social alienation exacerbated by the pandemic. (2) Methods: SPSS v.26 software was used to analyze quantitative data from questionnaires used in the study of social participation, as well as the pre- and post-test impacts, and MAXQDA 2020 software was used to analyze qualitative data from YouTube discussions about youth needs and strategies for their problems, as well as from focus groups. (3) Results: In S1, it was evident that young people’s expectations of participation in the community were not defined and that their expected participation in the community was of a weekly nature. They considered themselves to have a good sense of belonging to the community or group and had reasonable social self-efficacy. Girls showed higher scores in Expectations of Community Participation and Active Participation. In their positive development, they did not have a defined evaluation of their competence, but their connection with others was evaluated as good. Boys showed higher levels of Competence. They said that every week they make 1 h of their day available to help others, and they did not frequently report feelings of social alienation. In S2, the evaluation of the impact of the project generally showed an improvement in the action research skills of the participants. At the end, six projects were proposed. In the analysis of the participants’ voices, the themes related to Substance Use, Social Capital, and Love and Sexuality stood out with higher participation and lower participation in the themes of Diversity, Culture and Housing. (4) Conclusions: The results suggest a need to encourage social participation, active citizenship, and entrepreneurship, along with their knowledge and skills for action. The promotion of debate and knowledge on issues related to young people’s lives seems to be a priority, especially issues related to Diversity, Culture and Housing. The Dream Teens model may prove to be an important strategy in this work, suggesting that this project may constitute a relevant model for future work.

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, young people saw their lives suspended. Deprived of the traditional educational model, of their friends, and confined to their homes, they stressed strong and significant impacts on their lives at the level of physical and mental health as well as emotional and social well-being [1,2,3]. Often the target of investigations and interventions, many of them were also postponed in the hope of a return to normality, which took a long time to happen.

Recent models of youth development and problem prevention may adopt the perspectives of prevention, resilience, and positive youth development (PYD) [4]. Although it can have a variety of meanings, Whitlock and Hamilton [5] argue that the terminology of PYD can be associated with (i) a definition of the developmental process, (ii) a categorization of programs or organizations that provide youth development activities, or (iii) an outcome-oriented principle that focuses on the resources of this generation. PYD encourages involvement and promotes healthy habits among all young people, not only those at risk [6].

In contrast to a few decades ago, when developing skills and providing direct resources to young people was advocated as a means of avoiding a problematic life course, current PYD programs place a premium on human potential, as well as individual competence and plasticity [7].

Based on developmental systems theory [8], all young people have strengths that can be capitalized on to promote more positive development in the adolescent period, and PYD programs can, through leadership opportunities, support the building of more positive relationships, develop life skills, promote the development of the five Cs: caring, character, connection, trust, and competence [9], and contribute to a sixth C: contribution [10,11]. The same author distinguishes the female gender with higher averages in all five Cs [12].

Young people’s social participation, or, according to Lerner [10], contribution, is advocated as a basic right of this population [13]. By facilitating opportunities for involvement in their own development, it promotes the learning of knowledge regarding human rights as well as a more active citizenship [14].

In a review of current perspectives on PYD, Shek et al. [7] show the long haul of theoretical approaches that run through the deficit perspective, Benson’s assets, Catalano’s 15 PYD constructs, SEL socio-emotional learning, and the perspective of “being” with a focus on character and spirituality.

1.1. Youth Action-Research Programs

Developed in response to traditional models that only promote capacitation, participatory research programs move the researcher away from the domain [15], supporting PYD and psychological empowerment [16]. In a mentoring relationship between adults and young people, they facilitate power sharing during the process, consultation, skills development, discussion for social change, and building relationships with stakeholders [17]. In a conceptualization of these programs, Rodriguez and Brown [18], summarize them in three principles: (i) they focus on the life experiences and concerns of young people; (ii) the methodology and pedagogy are based on the collaboration and participation of young people; and (iii) they have a transformative characteristic that contributes to changing theories and practices that improve the lives of young people and their contexts. Although widely recognized for their importance at the cognitive, academic/vocational, social, and interpersonal levels of agency and leadership [19], these programs are still uncommon in Europe. Developed primarily in the United States, particularly in schools, e.g., [20,21,22], those developed in the community context are still uncommon.

Youth action research programs are described in the literature as promoting positive development as well as civic engagement [23]. In addition to promoting a positive impact on health and well-being, these programs are also promoters of agency, leadership, social-emotional, interpersonal, and cognitive development [19,24]. Prati et al. [23] report an increase in social well-being and participation among participants of a youth program. Even in a school context, a study by Taines [25] demonstrated that youth activism promotes a reduction in students’ feelings of alienation. Youth who participated in this program reported feeling less powerless and isolated [25].

Adapted to the digital age, YPARs have demonstrated a positive intersection with the use of technology [26].

1.2. Dream Teens Powered by Jovem Cascais

Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais was inspired by the Dream Teens network, an initiative of the Aventura Social Project team (http://aventurasocial.com/, accessed on 20 August 2022). This youth participation project was aimed at young people aged 11 to 18, providing tools and skills for empowering the youth voice in the identification of the needs and problems of their generation as well as strategies. The original Dream Teens project, which served as the model for this work, was designed to prevent alienation and increase the social capital of its participants.

With potential effects on social alienation resulting from estrangement from family and friends, the COVID-19 pandemic could reduce well-being and increase risk behaviors while also contributing to increased psychological symptoms, sadness, and lower life satisfaction [27].

At the community level and in partnership with Jovem Cascais (Youth Division)/Cascais Municipality, a study focused on social participation, active citizenship, and PYD was developed among the municipality’s residents (14–30 years old), along with the case study “Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais”, which created a network of 19 young people aged between 14 and 26. This project promoted the discussion of the main needs and strategies for youth problems, making them more active and socially participative and encouraging the development of action research and social entrepreneurship projects in the municipality.

2. Materials and Methods

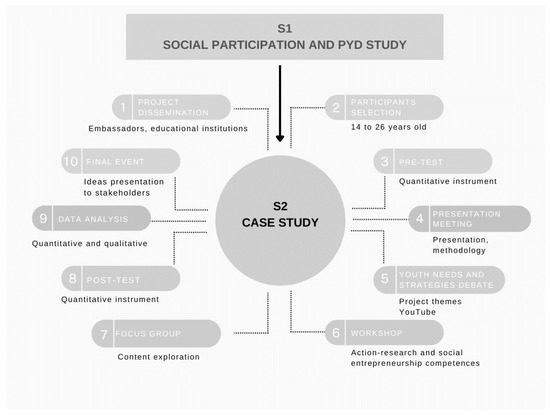

In this project, the following methodology (Figure 1) was developed in order to study social participation and PYD and also to elaborate on a case study in the encouragement of social participation, active citizenship, and social entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.

Work Methodology.

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Participants of Study—Social Participation and PYD Study Questionnaire

In total, this study received 437 responses, of which 378 were considered valid (after the exclusion of incomplete or duplicate responses). The responses were collected between May and August 2020.

The respondents were mostly female (65.3%) and of Portuguese nationality (82.8%), with a mean age of 18.76 3.541 years (minimum age was 14 and the maximum age was 30). The majority of the respondents were students (74.9%), with 50.5% in secondary education, 33.9% in higher education, and 15.6% in middle school.

2.1.2. Participants of Study 2–Case Study

A total of 32 participants were selected, corresponding to all the applications received (Min = 14 and Max = 26), 19 of whom attended the first meeting to learn about the project and its methodology. A workshop was developed with nine young people present in order to develop research-action and social entrepreneurship skills.

A space was created to debate the needs and strategies for the problems of young people through the YouTube platform (n = 17; Min = 14 and Max = 24), in which the most active participation of 12 elements was evident. A focus group was held (n = 9) to deepen the material collected on the platform.

Since not everyone answered both pre- and post-instruments, only seven answers were considered. With a mean age of 19.43 ± 3.36 years (Min = 16 and Max = 24), 57.14% were girls, and 57.1% attended secondary school.

At the end, six participants presented project ideas for employment and social entrepreneurship, volunteering, socio-emotional skill promotion, and research.

2.2. Procedure

The Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais project began in April 2020, with the dissemination of a study on social participation, active citizenship, and PYD of the youth living in Cascais.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the intervention work began with a call led by three ambassadors born and residing in the municipality, who, through dissemination posters, gave the moto for registration in the project.

In the initial phase, in order to establish partnerships, all schools and universities in the municipality were contacted via email. The dissemination included a link to a registration document that included: personal information registration with the option of submitting parental consent (18 years); a field to write a presentation text; an identification of the needs of young people living in the municipality; the respective strategies for their problems; and a motivation letter. Applications had to meet the inclusion criteria: age between 14 and 30 years and residence in Cascais (request for photo of student card). All candidates were integrated due to the small number of applications.

After this initial phase, a conference was held to present the project and its methodology, and a 2-h workshop was scheduled.

In the first phase of the project, participants were encouraged to discuss the following working themes: (1) Personal resources and well-being; (2) Social capital; (3) Love and sexuality; (4) Consumption and dependencies; (5) Leisure and sports; (6) Citizenship and social participation; (7) Culture; (8) Environment; (9) Diversity; and (10) Housing, in order to carry out a study of the main problems and needs of young residents of Cascais, as well as the corresponding strategies. The themes were based on the Dream Teens model, with themes 7–10 added at the request of the Cascais City Council. In this work, we created a YouTube channel (launching biweekly challenges in video and music format to collect the generation’s needs and strategies) and a WhatsApp group to allow better contact between participants and foster support and cohesion.

Subsequently, a new stage was initiated, allowing the natural selection of the most active and socially participative young people through the development of the workshop (2-h) with a fundamentally active methodology, a focus group, in order to discuss the content discussed on the YouTube platform. At the end of the training in action-research knowledge and the development of social entrepreneurship skills, an individual project proposal was requested. During the project’s development, continuous support was provided by the research team, and bimonthly meetings were scheduled with the young people between August and October.

At the final closing event of Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais, the individual projects were presented, with the participation of the scientific coordinator of the Dream Teens project, the regional director of Lisbon and Tagus Valley of the Portuguese Institute for Sport and Youth, I.P., and an assessor from the Cascais Municipality.

This work was integrated into the Dream Teens project, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lisbon Academic Medicine Center.

2.3. Instruments

In this project, four instruments were developed: (i) questionnaire for the study of social participation and PYD in Cascais; (ii) pre- and post-test for impact evaluation; (iii) challenges for collecting the needs and problems of young people, as well as strategies; and (iv) a focus group interview guide.

2.3.1. Instrument of Study 1-Social Participation and PYD Study Questionnaire

This questionnaire included questions related to sociodemographic data (age, gender, nationality, country of birth, level of education, and employment status); Expectations and Involvement in Social Participation and Positive Development, studied through the application of the Questionnaire of Expectations and Involvement in Social Participation and Positive Development (original instrument by the author Samdal and colleagues [28], adapted and validated for the Portuguese population [29]), based on the scales of community participation expectations, active participation, sense of belonging, and social self-efficacy.

In parallel, four scales of the Positive Youth Development Short Form Instrument (original instrument by Geldhof and colleagues [30], adapted and validated for the Portuguese population [31]) were included, namely: competence, connectedness, and contribution. As a complement to the study of PYD, a scale was included in the study of alienation [27].

This instrument was created on the Google Forms platform and had an average response time of 10–15 min.

2.3.2. Instrument of Study 2–Case Study

A total of 24 challenges were launched in video and music formats to identify the main needs of this generation and strategies for solving their problems. In order to deepen the collected material, a focus group with a semi-structured guide was carried out (e.g., in the challenge related to bullying and cyberbullying, you mentioned that this type of violence was a common behavior among young people. Do you agree? What strategies can you identify to minimize this problem?).

To study the impact of the project, an instrument was again created on the Google Forms platform, with a completion time of 5–10 min. This questionnaire included the collection of socio-demographic data (name, age, year of schooling, and gender); participation in leadership activities in the past year; expectations for the future (medium and long term); and action-research knowledge and skills (10 items; 4-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly agree and 4 = strongly disagree; e.g., “If I want to improve a problem in my city, I know how to collect data. For example, “If I want to improve a problem in my city, I know how to gather important data on the subject.” and “Young people have a Voice in what happens in this city.” and a 5-point scale in the expected impact of the project, where 1 means strong benefits and 5 means weak benefits.” An open question was included to create the opportunity for ideas and suggestions.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.1.1. Quantitative Analysis Using Software SPSS v. 26

Descriptive statistics were performed for all variables and dimensions (mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum). The mean scores of Social Participation and PYD based on gender, year of education, and region were studied using ANOVA and post-hoc (Tukey HSD) tests to analyze the differences between groups. The significance level was set at 0.05.

In the pre- and post-test, in addition to the descriptive statistics, a synoptic table (taking into account the small number of respondents) of the impact and their expectations was performed.

3.1.2. Qualitative Data Analysis Using MAXQDA Software

Data was obtained through the challenges posted on the YouTube channel and in the focus group, which were recorded at the time of their completion. Following a preliminary content analysis, all data was aggregated and coded into categories and subcategories based on the themes under consideration and their nature.

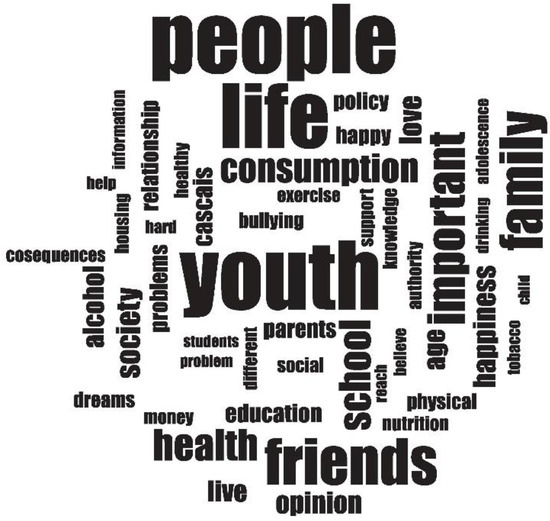

A word cloud enabled the visualization of the most frequent words in the discourse, and MaxMaps, with a hierarchy model for coding the themes, displayed the highest and lowest number of comments.

3.2. Study Results

3.2.1. Study 1-Questionnaire on Social Participation, Active Citizenship and PYD

In the descriptive analysis of the means of social participation and PYD, in each of the dimensions, the following results were found in the respondents: (1) Expectations of Community Participation (M = 2.47, SD = 0.853); (2) Active Participation (M = 1.75, SD = 0.608); (3) Sense of Belonging (M = 3.89, SD = 0.778); (4) Social Self-efficacy (M = 4.05, SD = 0.726); (5) Competence (M = 3.36, SD = 0.631); (6) Connection (M = 3.76, SD = 0.666); (7) Contribution (M = 2.01, SD = 0.787); (8) Alienation (M = 2.34, SD = 0.503); based on this data, it was interpreted that young people did not have well-defined expectations of community participation, not knowing whether in the future they would engage in activities or issues that would improve their community; their future active participation was expected to be weekly; they had a good sense of belonging to their community or group; and they considered themselves to have some social self-efficacy. As for positive development, they were not sure about their competence, but they were sure about their connection with others and rated it as good; on average, they revealed that they contributed 1 hour of their time each week to helping others; feelings of alienation were not often mentioned.

In the study of the means of social participation based on gender, statistically significant differences were found in the dimensions: Community Participation Expectations, F(1, 376) = 16.076, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.041, with girls standing out (M = 2.6, SD = 0.802); and Active Participation, F(1, 376) = 4.953, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.013, with females once again reporting a higher mean (M = 1.8, SD = 0.616). In the PYD study, statistically significant differences were found in Competence, F(1, 376) = 17.251, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.044, with boys showing higher competence (M = 3.54, SD = 0.651) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anova comparisons according to gender adapted [32].

3.2.2. Study 2–Case Study

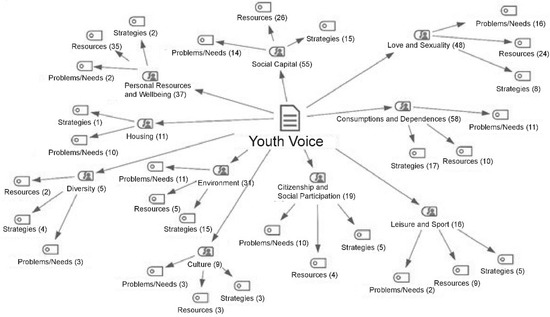

In a joint analysis of their responses obtained to the challenges issued on YouTube and in the focus group, a greater participation in the challenges related to Substance Use (codifications = 58), Social Capital (codifications = 55), and Love and Sexuality (codifications = 48) stood out. With a lower number of responses, Diversity (codings = 5), Culture (codings = 9) and Housing (codings = 11) stood out (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of Codes Model [Reprinted from Branquinho et al., 2021; [32]].

A word cloud (Figure 3) reveals the most frequent words in speeches, highlighting: young people, people, life, family, friends, and health.

Figure 3.

Word Cloud [Reprinted from Branquinho et al., 2021; [32]].

In the voice of the young, a summary table is presented (Table 2) with brief exemplary excerpts of the most discussed themes, namely: Substance Use; Social Capital; and Love and Sexuality.

Table 2.

Summary table: Voices of Cascais’ Youth.

All participants in the pre- and post-test had participated in a volunteer activity within the previous year. With regard to their medium-term objectives (5 years), they focused on continuing their academic career or working in their area of study, and in the long term (10 years), they planned to be established in their profession.

Overall, a positive impact was observed on their action-research skills and knowledge, and on their interest, involvement, and leadership in issues that improve their community (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre- and Post-test.

They emphasized the importance of face-to-face meetings in promoting group cohesion and facilitating debate in the pre-test and the weakness of the absence of face-to-face meetings and YouTube as a platform for debate in the post-test.

Even though the involvement of young people was not as expected, with only 12 of them participating more actively, it is believed that this decrease served as a natural selection of the motivated young people, since this previous selection was not carried out.

Considering the nine participants of the workshop to promote these skills and the submission of two employment and social entrepreneurship projects, two volunteering projects, one promoting socio-emotional skills, and one research project (Table 4), it is certain that they will contribute to a greater awareness of social participation and better health and well-being in the municipality.

Table 4.

Youth Ideas and their Objectives.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Based on these results, it is believed that this action-research model can be an important strategy not only for social participation, active citizenship, and social entrepreneurship but also for the fostering of positive youth development through YPAR using technologies.

In the initial study, the general study of the Social Participation Questionnaire and PYD of youth living in Cascais, it was found that they did not have well-defined expectations of participation in the community. It is not clear whether, in the future, they will be involved in activities or issues that improve their community context. Their future active participation should have a weekly character, a reasonable sense of belonging to their community or groups, and a feeling of social self-efficacy. A recent study developed with Polish youth does not reveal divergent results, showing that young people have a median tendency towards participation [33]. Since their competence is not well-defined, the way could be through the development of competence, motivation, and opportunities, as proposed by Michie et al. [34], a work that Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais tried to implement.

The study of gender differences showed statistically significant differences in the dimensions: Expectations of Community Participation and Active Participation, in which girls showed higher scores. Within the scope of the study on Health Behavior in School-aged Children/World Health Organization (HBSC/WHO) 2018, conducted in Portugal, higher expectations of community participation were corroborating among females [29]. The boys, on the other hand, stood out in terms of competence. Although several studies show that girls have higher averages in all five Cs (care, character, competence, trust, and connection) [12], the author Årdal et al. [35] confirm that boys have higher competence in their study. The dimensions Sense of belonging, Social self-efficacy, Connection, Contribution, and Alienations did not show significant statistical differences. In the HBSC/WHO 2018 Portugal study [29], boys had a greater sense of belonging and social self-efficacy.

Moving to the case study, the problems and needs of young people in the municipality, along with strategies, were evident. There was the highest participation in the challenges related to Substance Use, Social Capital and Love and Sexuality. This supports previous literature that identified youth participation as an agent of change regarding substance use because young people can be important producers of real data as well as prevention materials [36]. Jarrett et al. [37] argued that organized programs for young people are a context in which they are in contact with adults who can help them with resources that promote the development of social capital. With a lower number of answers, Diversity, Culture and Housing stood out. With young people leaving their parents’ house later and later, the topic of Housing may not emerge as important in these life stages. Moreover, less discussed are the themes of Diversity, Culture and Housing in the public sphere and in school settings, where there might be a lack of skills, motivation, and opportunities for their discussion. In their speeches, recognized as problems or strategies, the words “young”, “life”, “people”, “friends”, “family” often stood out.

Finally, focusing on the applied pre- and post-test instrument, an improvement in action-research skills at the level of knowledge and action expectations was revealed. The original study showed similar results in the improvement of action-research expectations [36,38,39]. At the end, after promoting their research-action competencies, six projects were under development.

Although social alienation was not particularly evident in the study carried out on the youth population during the pandemic period, studies have highlighted the feeling of disconnection from friends [1,2,3]. Given that participation in the Dream Teens powered by Jovem Cascais network promoted the social capital of its participants, enhancing relationships with their generation, professionals, and stakeholders, it is believed that this program was a promoter of greater social participation, active citizenship, and social entrepreneurship, preventing feelings of social alienation. At the same time, it supported the PYD through its three principles of effectiveness through participation programs: leadership opportunities, life skills development, and young adult mentoring [40].

5. Strengths and Limitations

As for strengths, the study of the panorama of social participation, active citizenship, and positive youth development at a municipal level is highlighted, work that, to the best of our knowledge, is pioneering. It is believed that this research can become an important resource for the work of action and intervention by Jovem Cascais/Câmara Municipal de Cascais. Alongside, a case study was conducted with the use of a tested and effective model—Dream Teens—from which the proposal of six ideas resulted.

However, despite its strengths and pioneering nature, there were some limitations in the initial study, as most participants were female and the sample was not homogeneous by years of schooling, eliminating the reliability of a comparative analysis by levels of schooling; as well as in the case study. The first is the scarcity of enrollees and the weak involvement in the participation of a considerable number of elements (although this is consistent with the initial study); the second is the impossibility of carrying out any kind of face-to-face activity, given the measures imposed in the control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the wide age spectrum of the participants made interaction and building rapport difficult. Third, the small number of participants prevents a generalization of the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B. and M.G.d.M.; methodology, C.B. and M.G.d.M.; software, C.B.; validation, S.S., T.G. and M.G.d.M.; formal analysis, C.B. and M.G.d.M.; investigation, C.B.; data curation, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B., C.N.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and M.G.d.M.; supervision, M.G.d.M.; project administration, C.B., J.S., I.S.M. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Cascais Municipality (no funding number).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project had the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Lisbon Academic Medicine Centre, through the Dream Teens project (41/16, 28 June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Study participants or their guardians signed a free and informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Cascais Municipality for funding the project, Aventura Social team, Jovem Cascais team, and Dream Teens.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Branquinho, C.; Kelly, C.; Arevalo, L.C.; Santos, A.; Gaspar de Matos, M. «Hey, We Also Have Something to Say»: A Qualitative Study of Portuguese Adolescents’ and Young People’s Experiences under COVID-19. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branquinho, C.; Santos, A.C.; Ramiro, L.; Gaspar de Matos, M. #COVID#BACKTOSCHOOL: Qualitative Study Based on the Voice of Portuguese Adolescents. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2209–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branquinho, C.; Santos, A.C.; Noronha, C.; Ramiro, L.; de Matos, M.G. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Second Lockdown: The 3rd Wave of the Disease through the Voice of Youth. Child Indic. Res. 2022, 15, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, S.; Memmo, M. Contemporary Models of Youth Development and Problem Prevention: Toward an Integration of Terms, Concepts, and Models. Fam. Relat. 2004, 53, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Hamilton, S. Understanding Youth Development Principles and Practices. Research Facts and Findings: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M.G.; Simões, C. From positive youth development to Youth’s engagement: The Dream Teens. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2016, 8, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X.; Chai, W. Positive Youth Development: Current Perspectives. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Lewin-Bizan, S.; Bowers, E.P.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Schmid, K.L.; Napolitano, C.M. Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. J. Youth Dev. 2011, 6, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Almerigi, J.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J.V. Positive youth development: A view of the issues. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M. Liberty: Thriving and Civic Engagement among American Youth; Sage: Riverside County, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Bowers, E.; Geldhof, G.J. Positive youth development and relational developmental systems. In Theory and Method. Vol. 1 of the Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science; Overton, W.F., Molenaar, P.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 607–651. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J.V.; Bowers, E.P.; Minor, K.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Schmid, K.L.; Napolitano, C.M.; Lewin-Bizan, S.; Lerner, R.M. Positive youth development: Processes, philosophies, and programs. In Handbook of Psychology; Lerner, R.M., Easterbrooks, M.A., Mistry, J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef.org. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/french/adolescence/files/Every_Childs_Right_to_be_Heard.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- United Nations. Youth Participation in Development: Summary Guidelines for Development Partners; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. Available online: https://social.un.org/youthyear/docs/policy%20guide.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Lake, D.; Wendland, J. Practical, Epistemological, and Ethical Challenges of Participatory Action Research: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of the Literature. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2018, 22, 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, E.J. Youth-Led Participatory Action Research: Overview and Potential for Enhancing Adolescent Development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.J.; Douglas, L. Assessing the Key Processes of Youth-Led Participatory Research: Psychometric Analysis and Application of an Observational Rating Scale. Youth Soc. 2015, 47, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L.F.; Brown, T.M. From Voice to Agency: Guiding Principles for Participatory Action Research with Youth. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2009, 2009, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyon, Y.; Bender, K.; Kennedy, H.; Dechants, J. A Systematic Review of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, Youth Outcomes, and Future Directions. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhout, R.D.; Collins, C.; Ellison, E.R. Examining Relational Empowerment for Elementary School Students in a YPAR Program. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 53, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E.J.; Douglas, L. The Impact of Participatory Research on Urban Teens: An Experimental Evaluation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voight, A. Student Voice for School-Climate Improvement: A Case Study of an Urban Middle School: Student Voice for School Climate Improvement. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 25, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Mazzoni, D.; Guarino, A.; Albanesi, C.; Cicognani, E. Evaluation of an Active Citizenship Intervention Based on Youth-Led Participatory Action Research. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamrova, D.P.; Cummings, C.E. Participatory Action Research (PAR) with Children and Youth: An Integrative Review of Methodology and PAR Outcomes for Participants, Organizations, and Communities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taines, C. Intervening in Alienation: The Outcomes for Urban Youth of Participating in School Activism. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 49, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L.; Kornbluh, M.; Marinkovic, K.; Bell, S.; Ozer, E.J. Using Technology to Scale up Youth-Led Participatory Action Research: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, S14–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, G.; Gaspar, T.; Branquinho, C.; Oliveira, M.L.; Matos, M.G. A alienação social e o seu impacto no bem-estar dos adolescentes portugueses. Rev. Port. De Psicol. Da Criança E Do Adolesc. 2019, 10, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Samdal, O.; Moreno, C.; Morgan, A.; Matos, M.G.; Baban, A.; Wold, B. Stimulating Adolescent Life skills through Unity and Drive (SALUD). In Proceedings of the HBSC Meeting, Luxembourg, 3 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho, C.; Tomé, G.; Gómez-Baya, D.; Matos, M.G. Participação social e o protagonismo jovem, num país em mudança de paradigma. Rev. De Psicol. Da Criança E Do Adolesc. 2019, 10, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Bowers, E.P.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Napolitano, C.M.; Schmid, K.L.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Creation of Short and Very Short Measures of the Five Cs of Positive Youth Development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, G.; Matos, M.G.; Camacho, I.; Gomes, P.; Reis, M.; Branquinho, C.; Gómez-Baya, D.; Wiium, N. Positive Youth Development (PYD-SF): Validação para os Adolescentes Portugueses. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2019, 20, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Silva, S.; Santos, J.; Sousa Martins, I.; Gonçalves, C.; Gaspar, T.; Matos, M.G. Dream Teens Powered by Jovem Cascais; Projeto Aventura Social: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Porwit, K.; Bójko, M.; Korzycka, M.; Mazur, J. Expectations for Engagement in Community Issues as Perceived by Young People. Dev. Period Med. 2022, 25, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Årdal, E.; Holsen, I.; Diseth, Å.; Larsen, T. The Five Cs of Positive Youth Development in a School Context; Gender and Mediator Effects. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2017, 39, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Matos, M.G. The “Dream Teens” Project: After a Two-Year Participatory Action-Research Program. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, R.L.; Sullivan, P.J.; Watkins, N.D. Developing Social Capital through Participation in Organized Youth Programs: Qualitative Insights from Three Programs. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 33, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, E.S.; Skobic, I.; Valdez, L.; Garcia, D.O.; Korchmaros, J.; Stevens, S.; Sabo, S.; Carvajal, S. Youth Participatory Action Research for Youth Substance Use Prevention: A Systematic Review. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, L.E.; Catalano, R.F.; David-Ferdon, C.; Gloppen, K.M.; Markham, C.M. A Review of Positive Youth Development Programs That Promote Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46 (Suppl. 3), S75–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasquilho, D.; Ozer, E.J.; Ozer, E.M.; Branquinho, C.; Camacho, I.; Reis, M.; Tomé, G.; Santos, T.; Gomes, P.; Cruz, J.; et al. Dream Teens: Adolescents-Led Participatory Project in Portugal in the Context of the Economic Recession. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).