Abstract

Young adults have experienced significant changes and cutbacks due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We investigated how young adults from Germany, Austria and Switzerland experienced their educational and vocational situation in the past and how they see their current situation and their future. The data was collected through expert and peer interviews, i.e., that some of our 17- to 20-years old interviewees were trained after the expert interview to conduct interviews with their peers themselves. The analysis shows challenges such as concerns over the socially perceived worthlessness of degrees during COVID-19, the prospective fear of difficulty in making contacts when starting in a new place, or the loss of motivation due to perceived omnipresence of school in everyday life. Changes such as a lack of communal celebration of graduation due to the elimination of school-based graduation activities, or developing independence after a distance learning experience due to required personal responsibility, could be seen. They used a variety of coping strategies, for example confrontive coping, distancing, seeking social support or escape-avoidance.

1. Introduction

Distance learning, schools operating in shifts, and children wearing masks in face-to-face classes became the norm for education during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was not an easy period, especially for young adults in transition to the next phase of life. The lack of opportunities made it difficult for them to come to terms with this change. There were challenges in both educational and vocational life. Regarding the situation of apprentices, Jürg Schweri reported theoretical and/or practical gaps in education due to a lack of infrastructure for distance learning at some schools, or in short-term apprentice work that was caused by the pandemic [1]. On the other hand, a need for rapid adaptation to the new circumstances has led to a “turbo-maturing process” in young adults, as stated by Schramm [2]. The “Generation Corona” buzzword is frequently mentioned, although there is critical discourse about the extent to which the term has positive or negative connotations. For example, Anger et al. [3] argued the predicted long-term consequences, such as the difficulties of young adults to be integrated into the labor market, while Huber et al. [4] and Maaz [5] argue for a differentiated understanding and an analytic approach in the discussion, and a resource-oriented approach in the education system. Many things could have been learnt during the pandemic, like dealing with crises or coping with an uncertain und unpredicted situation, for example.

Various studies conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed the effects of crisis-related situational changes in general conditions on adolescents’ and young adults’ lives at school, and these form a fundamental basis for the present sub-study. These findings reveal the educational challenges for young adults triggered by the pandemic. The findings of the School Barometer (www.Schul-Barometer.net (accessed on 7 July 2022)), see Huber et al. [4,6,7,8] for instance, have already sketched a clear picture of sentiment towards the challenges that schools faced in spring 2020. However, it is of interest how these occurring challenges, which were especially big for young adults in their transition from their high school or apprenticeship graduation to their further educational or working live, were experienced; how they changed during the pandemic and which differences can be seen between the three countries of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, in which political measures regarding COVID-19 highly differed. Hence, the present sub-study concerns the research question: How did COVID-19 impact the transition (e.g., financial circumstances, working during COVID-19, graduating during COVID-19, preparing for future school and vocational qualifications) and the educational lives (e.g., structuring their learning, motivating themselves, interacting with peers, parents and teachers) of young adults (17- to 20-years old), and how did they cope with the perceived impacts?

1.1. State of Research

1.1.1. Perception of Distance Learning and the Impact of School Closures on Adolescents

The School Barometer [6] was launched to describe and assess the perceived school life regarding digital learning (e.g., technical resources, learning support, opinions on digital learning), communication (e.g., reactions to the school closure, information on the changes), burden, and wishes, in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland during the first lockdown in spring 2020. The survey was filled out by various stakeholders involved in the school system, including students, parents, administrators, staff, supervisors, and support workers. The findings show that a feeling of security when planning and enforcing regulations during distance learning is of great importance for all the stakeholders involved, and good communication and constant exchanges are required between all groups. Distance learning is viewed differently: for example, some young adults have expressed positive views on it, while others have had difficulty with online-based instruction [4]. Fifty-two percent of the students surveyed said that they tended to feel or felt a great deal of stress at the time. That the impact of the pandemic has led to high levels of stress among adolescents has also been shown in other studies [3,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Contextual analyses have revealed that students who spent 25 h or more in distance learning were better able to: structure and plan their daily routines; experienced greater learning growth and more frequent monitoring of learning tasks by teachers; engaged in more leisure activities such as sports or reading; and did not feel like they were on vacation when compared with students who spent less than 9 h per week in learning time. Large differences in weekly learning time and motivation also predict a growing scissor effect, with primarily lower structuring and planning skills, and lower competence in self-regulated learning, followed by limited resources and lack of family support, being the cause for socioeconomically worse-off students falling behind [7].

Another impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was a change in the adolescent’s sleep timing and a resulting change in their daily routines [15]. As a survey study by Margolius et al. [16] shows, 29% of students started to feel less connected to classmates or their school community during distance learning.

Various studies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23], looked into physical, psychological, or social health. Dale et al. [19] found an increase in depression, anxiety, insomnia, and disordered eating as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic on apprentices in Austria. Li et al. [21] analyzed an association between higher levels of electronic learning time with higher levels of depression and anxiety among adolescents in Canada. Moreover, they found an association between higher levels of TV or digital media time with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and inattention, as well as an association between higher levels of video game time and higher levels of depression, irritability, inattention, and hyperactivity. Another set of studies looked into youth unemployment [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Lambovska et al. [28] analyzed the development of youth unemployment in several European countries based on the Eurostat database. They found an increase of youth unemployment, for instance, in Hungary, Italy, Belgium, Lithuania, Latvia, and Ireland. However, they identified the Czech Republic with a factor of 2.19 increase, and Estonia with a factor of 2.5 increase at the end of 2020, compared to the end of 2019, as the most affected countries. Furthermore, several authors dealt with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on specifically vulnerable youth [31,32,33,34,35,36].

1.1.2. The Impact of School Closures on Students at Risk

The findings of Huber and Helm [10] are supported by Goldan et al. [37], who called for more support services for students with special educational needs. Youth researchers Schnetzer and Hurrelmann [14], also noted that young people who do not graduate from school often feel helpless. As Dohmen and Hurrelmann’s [38] book concluded, existing social inequalities in the education system have worsened due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Following on from this, it should be noted that, as shown by the findings of the YASS studies, education shapes life satisfaction. Young adults without education are less satisfied than those with post-compulsory education [39,40]. Thus, the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on education, or educational inequities, could entail a chain of further consequences for young adults. Regarding coping with the effects of the crisis, Andresen et al. [9] were able to confirm from clients in residential treatment that adolescents who had a good sense of well-being before the crisis, and who had plenty of contact with friends and family, saw something good from the crisis situation. They felt that they could cope well with it.

1.1.3. The Effect of the COVID-19 on Transitions of Young Adults

The “Generation Corona” [41] survey in Austria revealed the fear that the economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis would have to be borne by the young generation. It is feared that future career opportunities will be limited [13]. In fact, the “Nahtstellenbarometer” shows that 17% of youth who graduated from compulsory school in the summer of 2021, and 16% of those who were due to graduate in the summer of 2022, have changed their education plans [42].

A study in England shows that 57% of students were of the opinion that COVID-19 worsened their job skill acquirement, and about 20% failed at finding an internship or job [43].

1.1.4. How Adolescents Dealt with the Political Measures

In terms of engagement with politics per se, it is clear from the findings of the YASS study that young males show a higher political participation than young females [44]. In Switzerland, it is apparent that political measures are generally rated as adequate [10]. In the “Youth in Germany” trend study, a high level of caution on the part of young people was still evident in summer 2022 [14]. For example, many still abstained from attending parties and had themselves tested regularly.

As a counterpoint to the increase in psychological stress resulting from the crisis, a positive effect was seen by an increase in solidarity among young people, which they considered a result of the effects of the crisis [45].

1.1.5. Young Adults’ Coping Strategies with the Pandemic

With regard to dealing with the effects of the crisis, various studies have mapped the choice of appropriate coping strategies (see Section 2.2). A study by Al-Yateem et al. [46] showed “planful problem-solving” to be the most chosen strategy. Another study by Alkaid Albqoor et al. [47] identified “positive reappraisal” to be the most frequently chosen coping strategy and “seeking social support” the least chosen among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. “Escape–avoidance” was more prevalent among female adolescents than male adolescents in this regard. This coping strategy is considered problematic, as it leads to higher risk of chronic health problems and social disintegration [46,47,48]. It is clear that adolescents in Saudi Arabia perceive much social support from friends and families. To this end, it can be seen that social support reduces the risk of negative effects of a crisis and contributes to choosing meaningful coping strategies [46,47,49]. Regarding gender differences, Alkaid Albqoor et al. [47] found escape–avoidance to be a more frequent choice among female adolescents than male adolescents. However, they see cultural reasons behind it, such that families apply much stricter rules to girls than to boys, and female children are subordinate to male children.

2. Design of the Study

2.1. Research Questions

The current state of research shows that the crisis situation has had far-reaching consequences for young adults. Quantitative studies have been able to bring out the central school challenges, but the description of the background of the findings, the illumination of the individual ways of dealing with them, as well as the localization of possible contextual conspicuities and coping strategies, are missing. Against the background of the findings from the different surveys described above, the aim in the present interview study is to understand the various context-based views, experiences, perspectives, opinions, concerns, and desires, of young adults. The focus is on young adults in transition from school/training to a new stage of life, and the analyses are intended to show individual modes of action under external conditions that are currently more difficult. Thus, the present findings allow for an observation of how young adults deal with educational and vocational challenges, exemplified by the ongoing pandemic situation. In relation to the findings of the School Barometer, this study wants to contribute in terms of “responsible science” to the knowledge base on the experiences and on the effects of the crisis situation in an international comparison.

From this, the following research questions emerge:

- (1)

- Transition: how did COVID-19 impact the transition (e.g., financial circumstances, working during COVID-19, graduating during COVID-19, preparing for future school and vocational qualifications) of young adults (17- to 20-years old); what led to these consequences; how did they change from spring 2020 till spring 2021; and what differences can be seen between the three countries?

- (2)

- School: how did COVID-19 impact the educational lives (e.g., structuring their learning, motivating themselves, interacting with peers, parents and teachers) of young adults (17- to 20-years old); what led to the these consequences; how did they change from spring 2020 till spring 2021; and what differences can be seen between the three countries?

- (3)

- Coping: how did young adults (17- to 20-years old) cope with the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from spring 2020 till spring 2021 on their lives (e.g., school, transition, free-time, friends, partners, family, personality)?

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Derived from the research questions, our study is based on different theoretical models and perspectives. To embed our study and to be able to answer the research questions (in terms of analyzing, interpreting, and discussing), it is of relevance to know: what our sample goes through during adolescence in general; what abilities are needed to do so; what the function of school is; and how crises are being coped with.

2.2.1. Development during Adolescence

Quenzel and Hurrelmann [50] divided youth phases into the early adolescent phase (age 12–17), the middle adolescent phase (18–21), and the late adolescent phase (22–30). In the second criteria, the main focus is on discovering one’s own identity [50] (p. 44). With regard to historical development, the authors spoke of an “adultization” of the youth phase and a “juvenilization” of the adult phase, due to an increase in social and economic expectations. Thus, content intended for adults is increasingly made available to adolescents, while the high level of skills shown by youth is increasingly demanded of adults and must be demonstrated by them in order to keep up in the professional life (e.g., digital skills). The specific challenges that adolescents and young adults face are referred to as developmental tasks [51]. During adolescence, these include building relationships with peers, becoming independent of parents, preparing for further school or vocational careers, forming values, and striving for socially responsible behavior. In young adulthood, this includes choosing a partner, starting a family, finding housing, entering the workforce, assuming responsibility as a citizen, and finding an appropriate social group. Following this, Hurrelmann [52] (p. 95) highlighted the four central themes of qualifying, bonding, consuming, and participating.

2.2.2. Required Abilities to Develop

This requires a high tolerance of ambiguity, defined as “the ability of people to let conflicting needs and views coexist” [53] (p. 16). This is required, for example, when there is a contradiction between the required behavior in a situation and the expected behavior [54]. Here, ambiguity tolerance is classified as low when the individual wants to have the experienced tension quickly averted without dealing with it and/or the situation is considered threatening; whereas high ambiguity tolerance allows for active engagement with the relevant options or different opinions and/or the assessment of the situation as a challenge [54,55,56,57].

The theme of resilience can also be linked to this. In terms of invulnerability, this is about enduring and mastering crisis situations. The required strength of resilience is contextually dependent on external and internal determinants, whereby protection has a supporting effect [58].

It can also be assumed that adolescents need a stable self-concept in order to cope with the challenges they face with individual goals [59]. Furthermore, factors such as perceived self-efficacy are relevant. Self-efficacy is related to self-regulation, which is based on a certain degree of autonomy. According to Burchardt and Holder [60] (p. 8), autonomy circumscribes the degree of freedom of choice and control a person has in significant areas of their own life. Similarly, the study is based on the capability approach of Sen [61]. Last but not least, well-being is an important condition in each life state. Ryff [62] (p. 101) defined six dimensions that are crucial for a good well-being, namely: self-acceptance; positive relations with other people; autonomy; environmental mastery; purpose in life; and personal growth.

The focus is on perceived opportunities for realization and the achievement of life goals. The “Generation Corona” sub-study is subject to the aforementioned approach of a stable subjective life concept with individual life perspectives as a prerequisite for personality formation and situational coping with action requirements [59].

2.2.3. Function of School and Factors to Access Educational Paths

With regard to the role of school, according to Fend [63], four social functions are to be mentioned: social integration; allocation, namely the allocation of social positions; qualification for vocational tasks; and enculturation, that is, the introduction to the cultural heritage of the community. It should be mentioned that various aspects such as the social origin of the family still play a major role regarding the accessibility of educational paths.

2.2.4. Coping Strategies during Crises

Another question is how the effects of crises are dealt with, namely, the coping strategies that exist. There are various theoretical models for this e.g., [64,65,66], whereas for the present analysis, the model of Folkman et al. [66] was used because it is subdivided in a fine-grained way, and therefore the text modules can be assigned concretely for the following interview analysis. They divided the coping strategies into: (a) confrontive coping; (b) distancing; (c) self-controlling; (d) seeking social support; (e) accepting responsibility; (f) escape–avoidance; (g) planful problem-solving; and (h) positive reappraisal.

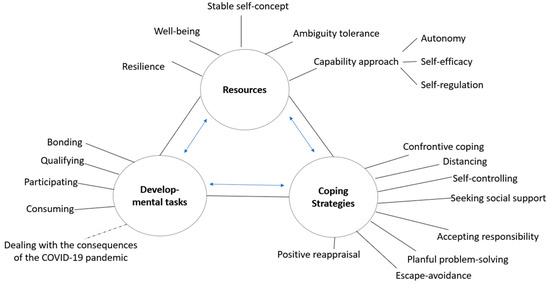

All in all, we can see certain tasks that adolescents must overcome (during adolescence per se and during crises in particular) demands that underly these tasks and some resources that are relevant to fulfill the demands. We argue that the resources needed to fulfill the developmental tasks are of the same importance to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, as the crisis constitutes another challenge just as the ones occurring during adolescence in general.

The theories being used in this study can be seen as complement as to tasks, demands, and resources in the phase of youth and young adulthood (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Developed model based on the theoretical framework.

2.3. Sample

The interview partners included 23 young adults (six from Germany, 10 from Austria, and seven from Switzerland) aged 17–20. The age range was chosen with a view to focusing on young adults in transition. Hereby, it has to be stated, that a sample size of 23 adults is rather limited. The study may therefore be indicative but not representative. However, certain criteria were defined to recruit an as heterogeneous sample as possible. Hence, following the principle of maximizing variance [67], the sample differed in various relevant characteristics, such as place of residence, gender, educational history, and other personal, as well as sociodemographic characteristics. It thereby contributes to the triangulation of the data. The surveys were conducted in three countries, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, and included participants from both rural and urban regions. Sampling was based on the defined maximum contrasting characteristics (country and place of residence, i.e., rural/urban, gender, educational history, and current activity). The criteria-driven case selection [68] (p. 39) served to achieve a large heterogeneity, so as to account for maximum diversity. Table 1 shows more details of the participants.

Table 1.

Details of the interviewees.

2.4. Data Collection

The semi-structured approach chosen for the interview was particularly suitable for the present study, since the changes experienced in the lives of the young adults are of interest in the topics of school and transition, which represent the upper categories in the subsequent analysis. The questions, which were revealed in advance to the participants, sought past, present, and future perspectives on their experiences, opinions, concerns, and wishes. They were asked in a semi-open form so that specific aspects could be dealt with in more detail.

The interviews were conducted and recorded between March and May 2021 either via Zoom (15 interviews) or in person (eight interviews). The interviews were all taken in German or Swiss German, respectively. Some were conducted via a multiplier system based on a three-stage procedure. The multiplier system is characterized by the training of selected individuals who subsequently serve as actors—in this case, peer interviewers—and lends itself well to the selected target group, in that a conversation among peers can lead to a high level of interviewee engagement, while also allowing for the participation of young adults in the research process, which in turn leads to deeper engagement on their part with the topic [69]. Four of the interviewees expressed interest in participating as multipliers. They were subsequently trained to conduct interviews before they interviewed their peers on the relevant topics. The training lasted about 45 min, took place via Zoom, and included information on basic aspects of interviewing as well as compliance with and observance of ethical aspects. Hence, they were rewarded through acquiring research skills. Moreover, we gave them a little gift afterwards as a token of our appreciation. The interviews were conducted via Zoom over a duration of approximately 60 min. The young people interviewed their peers using the youth peer interview method. As Lile [70] put it: “leaving youth voice out of a research project that focuses on youth issues is a strategy that fails to acknowledge or question the assumptions of traditional hierarchies in research” (p. 7).

Arguments for the use of the youth peer interview method include the development of the interviewers’ professional competencies and the validity of the data. According to White and Klein (2008, as cited in [69]), the personal perception of a situation and a context influences the behavior and nature of one’s own statements, since there is a tendency to adapt to the audience—in this case, the interviewer—in order to slip into the supposedly expected role. The interview guidance by peers could therefore contribute positively to the authentic answer behavior of the interviewees.

In total, 11 interviews were conducted by the researchers and 12 interviews were conducted by the four multipliers (3–5 interviews per multiplier). Afterwards, all of the 23 interviews were subsequently transcribed by the researchers based on the rule system of simple transcription according to Dresing and Pehl [71] (pp. 20–23). In the interviews taken by the youth researchers, in comparison to the interviews taken by the adult researchers, we saw certain differences in the material such as a slightly more open communication about topics like drugs, relationships, and breaking rules. However, we treated the material equally in our analysis as one cannot be sure whether the dialogues between the adolescents effectively were more honest, or if some made up some aspects to coincide with a certain image. In line with the chosen evaluation method of structuring the content, non-verbal communication was not transcribed.

2.5. Data Analysis

The method of qualitative content analysis according to Mayring [72] was chosen to evaluate the interviews. This method is used to locate and present the central statements of the interviewees and is composed of the juxtaposition of units of analysis (categories) and the corresponding text statements of the interviewees, enabling the contextual location of the corresponding statements [73].

In this context, 17 of the 23 interviews were systematically processed using a thorough coding system, and the remaining six were examined in a complementary, supplementary manner. This was decided for as we seem to have achieved a saturation after 15 interviews and no new thoughts or perceptions occurred.

In order to obtain the desired identification of the core topics in the two thematic areas in accordance with the research question, content-structuring content analysis was applied subordinately. Here, the upper categories are formed deductively from the individual topic complexes of the interview guide, namely, in the case of the present analysis, into the areas of ‘school’ and ‘transition’, which represent the structure of the category system. To form the subcategories, inductive codes were formed on the basis of the central statements from the interview transcripts. For the formation of these inductive codes, the procedure of summary content analysis based on Mayring [74] was applied as a combinatorial addition, which, according to Mayring [74] (p. 67), should be straightforward in qualitative content analysis. From paraphrasing the text data to generalization and reduction, it is possible to highlight the central aspects of the interview statements. This allows the material to be: “evaluated according to content-analytical rules without falling into rash quantification” [72] (p. 1). Accordingly, the corresponding text material was reduced to the central content of the statement.

Furthermore, since coping strategies needed to be analyzed, a third category was formed deductively with the help of a coding guide. Since we expect an impact of the pandemic on different areas of the interviewees’ lives (e.g., school, transition, personality, family, partners, friends, and leisure time), we analyzed their coping strategies overarching on all challenges mentioned. This category contains the coping mechanisms based on the coping strategies described in theory according to Folkman et al. [66], i.e.,: (a) confrontive coping; (b) distancing; (c) self-controlling; (d) seeking social support; (e) accepting responsibility; (f) escape–avoidance; (g) planful problem-solving; and (h) positive reappraisal. For this part of the text analysis, namely the allocation of the text passages to the coping strategies, we refer back to the items of Folkman et al. [66] (pp. 993–994). We defined in the coding guideline, that the text passage should correspond to at least one item of the definition (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Coding guideline according to Mayring [72,74] for deductive coding of coping strategies based on the theory of Folkman et al. [66] (pp. 993–994).

3. Results

The compilation of results in this article corresponds to an abridged version of the analyses by Egger and Huber [75]. This section starts with the transitions as these have not been specifically highlighted in many other studies so far. Then, schooling will be presented, where a high congruency to other studies can be seen. However, there are some new and interesting aspects regarding the reasons behind the perceived consequences, the changes over time, and the country differences, which we were able to depict thanks to our sample living in Germany, Switzerland, or Austria. The chapter ends with the coping strategies; it can be seen how young adults reacted to and how they coped with the challenges in schooling/education and transition/work.

3.1. Transition or Work

Statements about transition could be divided into the subcategories of joyless completion and uncertainty, with resulting impulsiveness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inductive coding: findings on the area of “transition”.

The majority of interviewees, who were right before the “Abitur” or “Matura” exams at the time of the interviews, had a negative view of graduation during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of the German and Austrian interviewees, graduation ceremonies such as “Matura/Abi” balls were canceled, about which they felt frustration and dissatisfaction. They missed celebrating their graduation together with their classmates (Table 3, excerpt 1). On the part of the Swiss interviews, an enormous appreciation was shown in this regard, since they decided not to cancel “Matura” trips and graduation parties. Some of the interviewees worried that their degrees could be considered worthless by society.

A lack of preparatory offers, such as internships or preparation events, led to planning uncertainty. Plans that had already been made, such as mid-year trips, were in some cases no longer feasible. As a result, decisions were characterized by a great deal of impulsivity since they had little possibilities in preparing for their future plan and rather decided for anything instead of ending up doing nothing after graduation (Table 3, excerpt 2). There was also the fear of entering a new phase of life. The young adults were afraid that the next step would take place through distance learning, as this would mean that neither the right atmosphere would be experienced nor new contacts would be made.

Regarding financial worries, there is the possibility to apply for scholarship, but there are limits to earning money besides that. Thus, many students decide to find themselves a student job. The interviewees therefore talked about financial worries due to restricted job offers resulting from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. School

The themes identified could be categorized into individual-, lesson-, and teacher-level subcategories, as shown in Table 4. As the political measures were different between both the countries as well as the cities, and constantly changed, the statements refer to different forms of schooling such as learning from home, learning in school while having certain pandemic-related rules (e.g., masks), or having a mixed form of learning from home and at school. Since there have been constant changes and the interviewees talked about past, present, and future perspectives (in which they experienced all forms of schooling), we analyzed the data overarching without separating between the actual forms of schooling.

Table 4.

Inductive coding: findings on the area of “school”.

Challenges were apparent at various levels. It was said that the changes in teaching, in combination with a lack of leisure activities and the resulting omnipresence of school, led to a great loss of motivation (Table 4, excerpt 1). In particular, social contact was missing, since there would be a mutual incentive in class to learn, and classmates would normally act as drivers for learning (Table 4, excerpt 2). At the beginning, teachers used different tools, which led to chaos (Table 4, excerpt 3). While the school changes were described as challenging at the time of the interviews in Switzerland, since this was in retrospect due to relatively regular classes resuming, the interviewees from Germany and Austria still spoke of difficulties at the time of their interviews. Nevertheless, it was mentioned that it had become easier with time to divide up the tasks and find a good learning rhythm. In addition to various disadvantages, advantages were also mentioned. In particular, some of the interviewees appreciated the saved commuting time/cost and described their learning process as more efficient, with factors such as a large space and a quiet learning atmosphere being explained here as decisive for this. People who described themselves as shy assessed the lessons differently in some cases; for example, some described it as an inhibition to switch on the microphone and speak during digital lessons, as their name and face were visible to everyone. In the lecture hall, however, less attention would be paid to them, although others described it as a relief to be able to open up and communicate with others.

3.3. Coping Strategies

The following chapter shows the Coping strategies among young adults exemplified by certain quotes in Table 5.

Table 5.

Deductive coding: findings on the area of “coping strategies”.

Confrontive Coping: Above all, critical thoughts and inner rebellion on the part of the young people, were evident. They questioned political measures—also with regard to the differently chosen strategies in neighboring countries—and expressed frustration and anger (Table 5, excerpt 1).

Due to the strong desire for normality and a regular lifestyle without restrictions, the rules were not respected by all. Thus, there was talk of waiving the obligation to wear a mask and of attending privately organized parties exceeding the permitted group size (Table 5, excerpt 2).

Confrontive coping was thus justified by a lack of understanding of the rules, or by the severe lifestyle changes that the restrictions had entailed, and which were unacceptable to the young people.

Distancing: Distancing manifested itself in different forms or with different conditions. For example, some interviewees did not continue to follow the political decisions out of interest (Table 5, excerpt 3), and others were able to continue living their lives as before because the restrictions had little impact on their personal lifestyle (Table 5, excerpt 4).

Self-Controlling: A noticeable difference could be seen in how the impact of the crisis was shared with friends or family. Some of the interviewees stated that they had not talked about it much with others. This was due to a feeling of constriction that was already too great due to increased contact with family, or to getting used to reduced contact due to the contact restrictions. Thus, there were withdrawn individuals who had been feeling an even greater need for isolation over time (Table 5, excerpt 5).

Some had also, due to uncertainty about the new measures, slipped into more of an observational role, such as by paying attention to how others complied with and encountered the measures, and thus adapted to them rather than actively talking about them (Table 5, excerpt 6).

Further, the change in perspective was also evident through attempts by the interviewees to put themselves in the shoes of policymakers and thus develop an understanding of the measures and be better able to cope with the effects for themselves (Table 5, excerpt 7).

Seeking Social Support: Another coping strategy was discussing concerns with others and seeking help. Interviewees reported that they had supported each other by sharing their negative thoughts and worries with each other. Additionally, a new meaning of relationships in terms of a partner as an outlet against loneliness emerged; thus, the so-called “Corona Buddy” was cited (Table 5, excerpt 8).

Accepting Responsibility: The fact that young adults were also part of the crisis and had to share responsibility had been clearly communicated to them through the media, and by parents and schools. For example, interviewees indicated that they had stayed home to protect at-risk groups (Table 5, excerpt 9).

Escape–Avoidance: Some responded by escaping. This revealed various compensatory mechanisms, such as increased alcohol/drug consumption or gambling—predominantly among male adolescents—and increased media use. This was justified by boredom caused by the fact that they had more time and fewer distractions (Table 5, excerpt 10).

Planful Problem-Solving: Certain things seemed to have been learned during the course of the pandemic. Particularly in terms of school, the interview statements revealed the strategies the interviewees had developed after initially being overwhelmed in terms of more efficient learning (Table 5, excerpt 11).

Positive Reappraisal: Personality development was also evident in some young adults. They mentioned increased self-reflection and the use of time to deal with their personal life goals, needs, and views (Table 5, excerpt 12).

4. Discussion

4.1. Transition

Referring to the allocative function of schools by Fend [63], the dependence of various reciprocal conditions can be seen in particular. Examination results, for example, determine the further options of young adults with regard to their vocational or academic careers, whereby the former depend on various internal and external determinants that have been strongly influenced by the pandemic. For example, externally, there were differences in parental support options and home spaces during distance learning; internally, there were different ways of coping with psychological stress and differences in self-regulation and resilience, which in turn affected performance in exams—some recorded better and others worse grades during the pandemic. Particularly stressed young adults would have needed more support during the pandemic, including support in transition planning. This was exemplified by an interviewee who described having been in therapy for several years due to depression, and drinking more alcohol during the pandemic. This is also consistent with the statements of Huber and Helm [7], Dohmen and Hurrelmann [38], as well as Schoon and Henseke [43], who postulate for greater support for students at risk during times of crises.

According to Havighurst [51], when coping with transition, both vocational or academic career entry is also counted among the developmental tasks. According to the interviewees, this was particularly challenging during the pandemic. As the young adults mentioned, the lack of preparatory offers was particularly aggravating, leading to changes in the plans and created additional uncertainty.

Uncertainty about the future also coincides with the current findings of other studies by Ö3 [41] or Golder [42]. Moreover, this goes hand in hand with the fifth dimension, according to Ryff [62], namely the existence of life goals as a contribution to well-being. The limited exposure to further opportunities makes it more difficult to deal with life goals because, as the young adults mentioned, there was no opportunity to prepare for their future and create plans for transition.

What comes to the fore here, following the capability approach of Sen [61], is how the realization opportunities were ultimately perceived.

Again, insecurity with regard to the perspective of entering university plays a role here. Furthermore, especially in Germany and Austria, financial worries due to a lack of funding and/or a lack of vacation/part-time jobs, were mentioned. The fact that financial worries were mentioned less in Switzerland than in the other two countries could also be related to the difference between the length and strength of the measures and the labor sector affected by them in the three countries.

4.2. School

The aspects mentioned in the area of schooling largely correspond to the findings of studies already conducted on distance learning, such as the ones by Huber et al. [6], Andresen et al. [9], Anger et al. [3], Bosshard et al. [10], Huber et al. [6], Jenkel et al. [11], Pro Juventute [12], Schabus and Eigl [13], and Schnetzer and Hurrelmann [14]. However, our findings show more background, such as the reasons behind the mentioned impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the changes over time, or the differences between the countries in relation to the differing political measures. In the comprehensive survey of the School Barometer, particularly with the first survey sub-studies, Huber and colleagues [6] showed that the challenges include loss of motivation, a poor place for learning, and difficulties in the rhythm of the day. Individual interviews also revealed the particularly large impact of the pandemic on already stressed adolescents already identified by research [7,13,14,38].

Through the interview situation, in contrast with the surveys, it was possible to go into more depth about the rationales, changes, and individual coping mechanisms. As the interviewees mentioned, they became more and more used to the situation during the year and were able to cope with it better, so that a good daily structure existed at the time of the interviews. We therefore can see a positive change, in contrast to the findings regarding the early negative change in their daily routines analyzed by Di Giorgio et al. [15]. Thus, adolescents seemed to grow from the challenges in this regard and were able to overcome them over time. Teachers had also shown improvement; hence, the effects of feedback from students were evident.

In addition, there were differences in the handling of a bad or dysfunctional learning atmosphere at home, from changing rooms to moving learning time to the night. For those who were withdrawn, the digital format seemed to be either beneficial or a hindrance: one interviewee described being able to open up better because of the distance; while another described never having dared to ask a question.

Differences between the countries became also evident: in Switzerland, people talked about the challenges mainly in the past; while in Germany and Austria, people talked about difficult present conditions. This could be related to the difference in the length and severity of the measures.

The gains were also in line with the findings from the School Barometer by Huber et al. [6], with the additional result that grades had improved for many. This is explained, for example, by the greater presence of school in the daily lives of young adults, or the changed formats for grading, which made cheating easier. Deterioration in grades, on the other hand, seem to be due to the lack of commitment to engage in online lessons. The independence gained as a positive effect of school closure, which was also perceived in this way by the adolescents, can be explained by the fact that autonomy and independence are regarded as essential components for well-being by Ryff [62].

4.3. Coping Strategies

The heterogeneity of the young adults was also evident in their coping strategies. Thus, the whole spectrum of coping mechanisms became apparent in the interview data. Similarly, it can be seen that some young adults used different coping strategies. Thus, it can be suggested that these were chosen contextually, or that the choice of strategy may have changed over time due to increased self-reflection, the value of experience, or peer observation of how the situation was being handled. The existing developmental tasks in the adolescent phase, described by Havighurst [51] and Hurrelmann [52], seem to have been made even more challenging by the crisis, as external conditions worsened due to the reduction of certain opportunities and further demands on youth being added. The “adultization of the youth phase”, as stated by Quenzel and Hurrelmann [50], is particularly evident in times of crisis and was manifested in the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, by the expectation to assume responsibility (protection of risk groups, compliance with measures). Furthermore, when considering the individual interview statements, the assumption remains that the choice of the respective coping strategy depends on certain personality traits and the expression of individual abilities, such as the strength of resilience, self-reflection, or the tolerance of ambiguity, which are described in more detail below.

The fact that rules were sometimes broken (confrontive coping), especially with regard to parties and meeting in large groups, shows the importance of partying and social contact as an important aspect of well-being among adolescents, as defined by Ryff [62]. Parties are also often associated by adolescents with culture, distraction, self-expression, belonging, and testing boundaries—all aspects relevant to youth—which in turn are also part of personal growth. That the adolescents suffered from these limitations is also consistent with the findings of other studies, like the one from Bosshard et al. [10] or Pro Juventute [12].

The fact that distancing was explained by a low level of interest in political decisions or acceptance of the rules, could also make visible differences in ambiguity tolerance, as it were, by linking back to the theory that individuals with a high tolerance for ambiguity engage intensively with an issue and illuminate different sides, while those with a medium or low tolerance for ambiguity tend to passively comply or not engage with it at all, as McLain explains [54]. Linking back to the body of research, it could be surmised that more female adolescents tend to do this, as male adolescents generally show a greater interest in politics, as stated by Mischler et al. [44].

As contextual factors can be seen, self-controlling was mainly chosen by individuals who described themselves as already being withdrawn/shy. This could be related to the fact that such individuals are generally used to frequently reflect on experiences and prefer to solve problems independently. The fact that there was also a change of perspective, and an attempt to put themselves in the politicians’ shoes, could indicate that people with a tendency toward self-controlling have a higher tolerance for ambiguity, namely, the constant aim to also see the positive sides of a situation characterized by contradictions, and to come to terms with ambiguity [54]. This would also be in line with Jenkel et al. [11], who were able to prove that adolescents who can also see good from a crisis—that is, who look at a situation from different angles and thus show a higher tolerance for ambiguity—are able to cope well with the crisis.

Interestingly, seeking social support and self-control, which seem divergent at first glance, were sometimes both used by the same interviewees. This shows that the choice of strategy is always very context-dependent. The strong need of adolescents for social closeness, an important part of well-being as defined by Ryff [62], becomes clear. The fact that even more relationships were entered into in order not to be alone during the lockdown could suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic also had an effect on the love lives of persons who tended to seek social support as a coping strategy. It is striking that help was sought from those who were close to the adolescents (family, close friends, partners), and not from external persons, such as therapists.

During the pandemic, young people were often confronted with the request that they should realize the need to take responsibility (accepting responsibility). As other studies have also shown [45], increased solidarity is evident. Thus, one can assume that frequent appeals from the outside to accept responsibility leads to it being perceived by young people.

That increased spare time led to boredom and corresponding compensation mechanisms is evident in the choice of escape–avoidance. Gender-specific abnormalities, as shown by Alkaid Albqoor et al. [47], were not evident here, which may be related to the cultural differences between Saudi Arabia and Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. However, the choice of compensation turned out to be different. For example, gambling seemed to have become more important for male adolescents, which anyway is of high relevance for many male adolescents because of their competitive spirit.

One individual mentioned drinking more alcohol to reduce boredom. This is consistent with the current research discourse, e.g., studies by Al-Yateem et al. [46], Alkaid Albqoor et al. [47], and Michou et al. [48], who state that the choice of this coping strategy can have an impact on the body and psyche. The contextual location of this shows that this person had already suffered from depression before the pandemic and was in therapy, as she stated. During distance learning, she had also stopped participating in school and had received lower grades. Thus, it could be surmised that individuals with low resilience are more likely to choose destructive compensatory mechanisms when bored. Similarly, the relationship between education and life satisfaction is again apparent [39,40].

The fact that planful problem-solving was increasingly used over time based on the initial experiences shows that young people grow to face crises and figure out their coping strategies over time. It is noticeable that planful problem-solving was used primarily when personal gains resulted from it. For example, it was mentioned that learning strategies were developed in such a way that the interviewees learned more efficiently and thus gained more free time for themselves. Linking back to the state of the research, it can be further assumed that individuals who are thus able to deal well and strategically with a crisis situation already have a good sense of well-being, as already analyzed by Jenkel et al. [11].

The fact that some adolescents dealt with their personal views, life goals, and needs due to the increased time with themselves, shows that forced isolation can lead to increased self-reflection and thus personal growth in adolescents. This engagement with personal life goals was already defined by Sen [61] as an important component for adolescent development and corresponding well-being. At the same time, the question arises whether the ability to self-reflect does not already exist, since this is an active process, and certain individuals do not tend towards a compensation mechanism (escape–avoidance instead of positive reappraisal) instead of self-reflection. Finally, it is noticeable that positive reappraisal was particularly evident in persons who also tended to be self-controlling.

4.4. Derived Theses

Based on the qualitative data analysis, the following theses can be formulated as assumptions to be verified for generalization. An elaborated summary of the wider study and recommendations for action for education, in particular schools and other social and educational institutions in a community, but also educational policy derived from them, can be found in Egger and Huber [75].

- The development of independence or indifference through distance education: Young adults became more independent or more indifferent during distance learning due to a lack of commitment through reduction or partial elimination of structures and the processes of action coordinated by the school.

- Time/cost efficiency or more learning difficulties in distance education: Young adults were able to save time/costs due to the elimination of commuting time/costs or experienced aggravated working due to a disrupted learning atmosphere at home.

- Distance learning improvement by adapting methodological instructional design to student feedback: Methodological distance learning design was adapted to student* feedback, which improved overall distance learning over time.

- The lack of variety favors loss of motivation: The lack of variety due to measure-related limited leisure activities favors a large, school-related loss of motivation among students caused by the perceived omnipresence of school in everyday life.

- The prospective fear of entering university and spontaneous decisions in choosing a course of study due to a lack of preparatory offers: Limited preparatory offerings for career and/or school transitions in young adults’ lives contribute to prospective entry anxiety, spontaneous decisions, and/or opting for a financially secure plan among young adults.

- Longer-term worthlessness of baccalaureate/baccalaureate degrees due to momentary stigmatization: The momentary stigmatization of baccalaureate/baccalaureate degrees as inferior could lead to longer-term stigmatization of Generation C degrees by society.

- Friendship dissolution due to lack of joint graduation opportunities and abrupt disengagement: The lack of graduation activities at school encourages more friendships to dissolve, since young adults cannot celebrate their graduation together and there is an abrupt disengagement from one another due to divergent further educational paths.

- Digital format as a help or additional inhibition for withdrawn persons: For withdrawn persons, a digital online format can be of benefit for finding contact and/or be perceived as an additional inhibition threshold leading to non-use.

- Confrontive coping may be chosen mainly by adolescents for whom the COVID-19 measures brought about a strong change in lifestyle (hobbies, partying, meeting lots of friends).

- Distancing may be chosen mainly by adolescents who have a medium or low tolerance for ambiguity, when they have little interest in politics, and/or the restrictions have not had a major impact on their lives (withdrawn individuals).

- Self-controlling may be chosen mainly by withdrawn/introverted individuals and/or those with a high tolerance for ambiguity.

- Seeking social support may be used mainly when an adolescent is in the environment of a trusted person who is close to them (family, friends, parenthood).

- Accepting responsibility may be used mainly when there is a strong external appeal to accept responsibility.

- Escape–avoidance may be used mainly when there is boredom and can lead to uncontrolled addictive behavior if the person has low resilience.

- Planful problem-solving may be used mainly when a crisis is prolonged and/or personal gains (e.g., more free time) result from the strategies used.

- Positive reappraisal may be applied mainly by adolescents who have high self-reflection.

4.5. Limitations

The analysis of this article is based on 23 interviews, some of which were conducted by interview partner who acted as multipliers. This type of data collection was intended to enable a higher validity of the data and the inclusion of young adults in the research process, with the additional goal of achieving a broader spectrum of interview partners and a higher saturation in the data material.

It must be taken into account that the results contain elements of positive bias: that is, the willingness to participate in the interview is characterized by a certain target group that took the time to do so, while the perspective of those who did not register for an interview is missing. The subjective coloring of the material was attempted to be counteracted as best as possible in the sense of triangulation by the predefined maximum contrasting characteristics. The research objective laid out beforehand allowed for a modified interview process, which led to saturation in the answers of the interviewees, but there was a risk of digression and of participants no longer communicating in a way that was relevant to the research question. This was especially the case with personal and/or emotional topics that were strongly marked for the participants (e.g., depression, previous burdens). Furthermore, a bias due to the previously formed opinions of the interview partners on individual topics by peers or the media, for example, cannot be ruled out, especially since there was a great deal of media coverage about COVID-19 and the effects of the measures that were taken. It is very important not to interpret the results as a generalization and to take external factors into account; for example, under normal circumstances—for instance, if there were no social restrictions or limitations on leisure activities—distance learning might be evaluated more positively by the interview participants.

4.6. Further Research

As an alternative analysis or presentation of the findings, psycho-social and socio-educational processes could be elaborated. Therewith, additional theoretical concepts on youth transitions could be further reflected. In order to test the theses and the following hypotheses and to generalize the results, the theses and hypotheses should be examined within a quantitative survey. In this way, it would also be possible to conduct a detailed quantitative analysis with regard to coping strategies. Further, there should be an investigation of the long-term consequences concerning, for example, planning uncertainty and spontaneous decisions, identity formation, as well as the recorded gaps in schooling—this in the sense of responsive research with ongoing investigation on the part of research and timely reaction on the part of practice through ongoing exchange between practice and science.

5. Conclusions

The present analyses add more in-depth insights to the quantitative findings of previous studies in an explanative way. It allows further quantitative study in an exploratory way. The interviews have made it possible to better understand the changes for the young adults due to the impact of COVID-19 and to shed light on the individual effects and ways of dealing with them.

The differences between countries stimulate assumptions to be further explored. For example, the relative harshness of the diverse measures in the different countries seems to have had a differing impact on perceptions of challenges in school and transition, i.e. for instance abrupt separations between friends due to elimination of school-based graduation activities or long-term effects of the school closures regarding catching up on educational content. Furthermore, graduation activities seem to be a very important part in the transition, as the interviews showed the lack of graduation activities to be a big burden in Germany and Austria, but that these could be carried out in Switzerland was valued. Another example is the lack of preparatory activities that has also made it more difficult for young people to come to terms with their own life goals. It is essential for young people to be supported and accompanied in their preparation for the next stages of their lives, after the pandemic.

The presumed link between the choice of coping strategy and individual abilities also shows that schools should not only impart knowledge but also take on the responsibility of educating core competencies like self-regulation, self-reflection, resilience, a variety of coping strategies, and tolerance of ambiguity in order to prepare them for their future ways of life. Thus, supporting adolescents’ personal development as well as strengthening these skills could lead to more appropriate coping strategies being applied in the individual context.

Further findings on the topics of school, transition, family, friends, politics, leisure, and personality, can be found in Egger and Huber [75], where further derived recommendations for action in practice can be seen.

In addition, the findings evaluated from the 2018/19 cohort from the Federal Youth Survey ch-x/YASS (www.chx.ch//YASS (accessed on 7 July 2022)) [76] were compared with the qualitative findings of the present interview study [77] in order to presume the findings that apply to the current generation—which is presumably shaped by the crisis—but which must be verified for generalization in follow-up surveys. Furthermore, different internal and external conditions for the choice of the corresponding coping strategies can be assumed, which already provide first ideas for intervention measures in practice, and also in the sense of Education for Sustainable Development and School of the Future. A representative study to verify, concretize, and elaborate the established theses around coping strategies is being planned.

As to the methodological approach, we especially would like to shed light on our positive experiences with the data collection process. Comparing the transcripts between the interviews conducted by the professional researchers and those of the adolescents, we saw that they talked in less inhibited ways about topics such as drug consumption, sexuality, or breaking rules, when being interviewed by their peers. What is more, the multipliers themselves explained that conducting these interviews helped them to understand different perspectives on dealing with the impact of the crisis. Thus, letting them participate, seems to have functioned as a coping strategy.

Reflecting on the use of the theoretical framework for data analysis, the description of findings and the conclusion on a meta level, it is interesting that theories even described back in the 1940s and 1990s are still working so much later—even though in such a very special situation like the crisis created by COVID-19. However, it is possible to edit, adjust and differentiate, and therefore to contextualize, refine, and modify the theory, using the further theoretical assumptions developed by the study.

Author Contributions

This piece of research was conducted in a full joint effort for all different parts of the research process. Conceptualization, M.E. and S.G.H.; methodology, M.E. and S.G.H.; software, M.E. and S.G.H.; validation, M.E. and S.G.H.; formal analysis, M.E. and S.G.H.; investigation, M.E. and S.G.H.; resources, M.E. and S.G.H.; data curation, M.E. and S.G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E. and S.G.H.; writing—review and editing, M.E. and S.G.H.; visualization, M.E. and S.G.H.; supervision, S.G.H.; project administration, M.E. and S.G.H.; funding acquisition, M.E. and S.G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and is part of the sub-studies of the School Barometer headed by Stephan Gerhard Huber.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In Switzerland, there is no approval of the ethics committee necessary for interview studies such as the one we have conducted. All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Most of them were of age. The others additionally provided a confirmation for participation by their parents.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study will be publicly available at the Swiss data warehouse FORSbase/SWISSUbase four years after the study.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the time and contribution of the interviewees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kunz, S. Lehrabschlussprüfungen—Ausbildung in der Pandemie: Lernende leiden unter Bildungslücken und drohen durch Prüfungen zu fallen. Luzernerzeitung Online. Available online: https://www.luzernerzeitung.ch/wirtschaft/lehrabschlusspruefungen-ausbildung-im-ausnahmezustand-lernende-leiden-unter-bildungsluecken-und-drohen-durch-pruefungen-zu-fallen-ld.2094107 (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Schramm, D. Ich sage “Generation C” kann auch ein Qualitätssiegel sein. [Twitter]. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dario-schramm-6977271b5_ich-sage-generation-corona-kann-auch-ein-activity-6770396964883337216-Zff7 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Anger, S.; Sandner, M.; Danzer, A.M.; Plünnecke, A.; Köller, O.; Weber, E.; Mühlemann, S.; Pfeifer, H.; Wittek, B. Schulschliessungen, fehlende Ausbildungsplätze, keine Jobs: Generation ohne Zukunft? Ifo Schnelld 2020, 73, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.G.; Helm, C.; Mischler, M.; Günther, P.S.; Schneider, J.A.; Pruitt, J.; Schneider, N.; Schwander, M. Was bestimmt das Lernen von Jugendlichen im Lockdown als Folge der COVID-19-Pandemie? Befunde aus dem Schul-Barometer für Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. In Generation Corona? Wie Jugendliche durch die Pandemie Benachteiligt Werden; Dohmen, D., Hurrelmann, K., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2021; pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Maaz, K.; Diedrich, M. Schule unter Pandemiebedingungen: "Lockdown"-"Hybridmodell"-"Normalbetrieb". Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 2020, 51, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.G.; Günther, P.S.; Schneider, N.; Helm, C.; Schwander, M.; Schneider, J.A.; Pruitt, J. COVID-19 und aktuelle Herausforderungen in Schule und Bildung. Erste Befunde des Schul-Barometers in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.G.; Helm, C. Lernen in Zeiten der Corona-Pandemie. Die Rolle familiärer Merkmale für das Lernen von Schüler*innen. Befunde vom Schul-Barometer in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. In Langsam vermisse ich die Schule...“. Schule während und nach der Corona-Pandemie; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, C.; Huber, S.G. Predictors of Central Student Learning Outcomes in Times of COVID-19: Students’, Parents’, and Teachers’ Perspectives During School Closure in 2020. A Multiple Informant Relative Weight Analysis. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 743770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, S.; Lips, A.; Möller, R.; Rusack, T.; Schröer, W.; Thomas, S.; Wilmes, J. Erfahrungen und Perspektiven von jungen Menschen während der Corona-Massnahmen. Erste Ergebnisse der bundesweiten Studie JuCo; Universitätsverlag Hildesheim: Hildesheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard, C.; Bütikofer, S.; Hermann, M.; Krähenbühl, D.; Wenger, V. Die Schweizer Jugend in der Pandemie. Datenauswertung des SRG-Corona-Monitors im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Gesundheit BAG; Sotomo: Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkel, N.; Schmid, M.; Günes, C. Die Corona-Krise aus der Perspektive von jungen Menschen in der stationären Kinder-und Jugendhilfe (CorSJH), Erste Ergebnisse. 2020. Available online: https://www.integras.ch/images/aktuelles/2020/20200902_CorSJH_ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Pro Juventute. Corona-Report. In Auswirkungen der Covid-19-Pandemie auf Kinder, Jugendliche und ihre Familien in der Schweiz; Pro Juventute Schweiz: Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schabus, M.; Eigl, E.-S. „Jetzt Sprichst Du!“—Belastungen und psychosoziale Folgen der Corona-Pandemie für österreichische Kinder und Jugendliche. OSF Preprints. 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/9m36r/ (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Schnetzer, S.; Hurrelmann, K. Trendstudie: Jugend in Deutschland. Jugend im Dauerkrisen-Modus—Klima, Krieg, Corona (Jugend in Deutschland-Trendstudie Sommer 2022); Datajockey: Kempten, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Di Riso, D.; Mioni, G.; Cellini, N. The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: An Italian study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolius, M.; Doyle Lynch, A.; Pufall Jones, E.; Hynes, M. The State of Young People During COVID-19: Findings from a Nationally Represntative Survey of High School Youth; America’s Promise Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Batalla-Gavalda, A.; Cecilia-Gallego, P.; Revillas-Ortega, F.; Beltran-Garrido, J.V. Variations in the Mood States during the Different Phases of COVID-19’s Lockdown in Young Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, N.; Castellanos Ryan, N.; Geoffroy, M.-C. COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental health: Emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R.; O’Rourke, T.; Humer, E.; Jesser, A.; Plener, P.L.; Pieh, C. Mental Health of Apprentices during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria and the Effect of Gender, Migration Background, and Work Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Dale, R.; Plener, P.L.; Probst, T. Pieh Christoph. Assessment of Mental Health of High School Students 1 Semester After COVID-19–Associated Remote Schooling Measures Were Lifted in Austria in 2021. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2135571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Tombeau Cost, K.; Charach, A.; Maguire, J.L.; Monga, S.; Crosbie, J.; Burton, C.; Anagnostou, E.; et al. Screen Use and Mental Health Symptoms in Canadian Children and Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ren, H.; Cao, R.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, C.; Mei, S. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.; Hughes, S.; Cotter, D.; Cannon, M. Youth mental health in the time of COVID-19. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achdut, N.; Rafaeli, T. Unemployment and psychological distress among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychological resources and risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonsi, L.; Bandiera, O.; Bassi, V.; Burgess, R.; Rasul, I.; Sulaiman, M.; Vitali, A. Tackling youth unemployment: Evidence from a labor market experiment in Uganda. Econometrica 2020, 88, 2369–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, M.; Kääriälä, A.; Lausten, M.; Andersson, G.; Brännström, L. Long-term NEET among young adults with experience of out-of-home care: A comparative study of three Nordic countries. Int. J. Soc. Welf. Forthcom. Article 2020, 30, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantová, M.; Arltová, M. Emerging from crisis: Sweden’s active labour market policy and vulnerable groups. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2020, 31, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambovska, M.; Sardinha, B.; Belas, J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Youth unemployment in the European Union. Ekon. -Manaz. Spektrum 2021, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyshol, A.F.; Nenov, P.T.; Wevelstad, T. Duration dependence and labor market experience. Labour 2021, 35, 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, M.; Murphy, M.; Whelan, N. Workfare redux? Pandemic unemployment, labour activation and the lessons of post-crisis welfare reform in Ireland. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 963–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdeselassie, T.; Emirie, G.; Abreham, I.; Gezahegne, K.; Jones, N.; Negussie, M.; Presler-Marshall, E.; Tilahun, K.; Workneh, F.; Yadete, W. Experiences of vulnerable urban youth under COVID-19: The case of street-connected youth and young people involved in commercial sex work. Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence, London, UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.gage.odi.org/publication/experiences-of-vulnerable-urban-youth-under-covid-19-the-case-of-street-connected-youth-and-young-people-involved-in-commercial-sex-work/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Palmer, A.N.; Small, E. COVID-19 and disconnected youth: Lessons and opportunities from OECD countries. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Raphael, J.L. Acute-on-chronic stress in the time of COVID-19: Assessment considerations for vulnerable youth populations. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 88, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliman Cohen, R.I.; Bosk, E.A. Vulnerable youth and the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, H.; Berdychevsky, L. COVID-19’s Impacts on Community-Based Sport and Recreation Programs: The Voices of Socially Vulnerable Youth and Practiioners. Leis. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, J.; Beauchamp, M.H.; Brown, C. The impact of COVID-19 on the learning and achievement of vulnerable Canadian children and youth. Facets 2021, 6, 1693–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldan, J.; Geist, S.; Lütje-Klose, B. Schüler*innen mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf während der Corona-Pandemie. Herausforderungen und Möglichkeiten der Förderung—Das Beispiel der Laborschule Bielefeld. In Langsam vermisse ich die Schule...“. Schule während und nach der Corona-Pandemie; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, D.; Hurrelmann, K. Generation Corona?: Wie Jugendliche durch die Pandemie benachteiligt wurden; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lussi, I.; Huber, S.G.; Ender, S. Wie die Bildungswege junger Erwachsener ihre Zufriedenheit beeinflussen. In Young Adult Survey Switerzland; Huber, S.G., Ed.; BBL/OFCL/UFCL: Bern, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mischler, M.; Huber, S.G.; Lussi, I.; Keller, F. Ausbildung und Lebenszufriedenheit. In Young Adult Survey Switzerland; Huber, S.G., Ed.; BBL/OFCL/UFCL: Bern, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ö3. Generation Corona. Online-Umfrage. 2021. Available online: https://www.generation-corona.at/ergebnisse.php?utm_source=int&utm_media=story (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Golder, L.; Mousson, M.; Venetz, A.; Rey, R. Nahtstellenbarometer 2022. Zentrale Ergebnisse März/April 2022. gfs.bern. Available online: https://cockpit.gfsbern.ch/de/cockpit/nahtstellenbarometer-2022/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Schoon, I.; Henseke, G. COVID-19 Youth Economic Activity and Health (YEAH) Monitor. In Career Ready? UK Youth during the COVID-19 Crisis; Briefing No. 2; Institute of Education, LLAKES Centre: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mischler, M.; Cattacin, S.; Lussi, I. Politische Partizipation. In Young Adult Survey Switzerland; Huber, S.G., Ed.; BBL/OFCL/UFCL: Bern, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Credit Suisse. Die politisierte Jugend bekennt Farbe. In Jugendbarometer 2020; Gfs.Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yateem, N.; Subu, M.A.; Al-Shujairi, A.; Alrimawi, I.; Ali, H.M.; Hasan, K.; Dad, N.P.; Brenner, M. Coping among adolescents with long-term health conditions: A mixed-methods study. Br. J. Nurs. 2020, 29, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaid Albqoor, M.; Hamdan, K.M.; Shaheen, A.M.; Albquor, H.; Banhidarah, N.; Amre, H.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A. Coping among adolescents: Differences and interaction effects of gender, age, and supportive social relationships in Arab culture. Curr. Psychol. 2021; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michou, A.; Mouratidis, A.; Ersoy, E.; Uğur, H. Social achievement goalds, needs satisfactions, and coping among adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Dawani, H.A. Social support and stress among university students in Jordan. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2008, 6, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenzel, G.; Hurrelmann, K. Lebensphase Jugend. Eine Einführung in die sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung (14., überarbeitete Auflage); Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst, R.J. Developmental Tasks and Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann, K. Jugendliche als produktive Realitätsverarbeiter. Zur Neuausgabe des Buches “Lebensphase Jugend”. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung/Discourse. J. Child. Adolesc. Res. 2012, 7, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, S. Grosses Wörterbuch Psychologie: Grundwissen von A–Z; Compact: Munich, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McLain, D.L. Evidence of the properties of an ambiguity tolerance measure: The multiple stimulus types ambiguity tolerance scale-II (mstat-II). Psychol. Rep. 2009, 105, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budner, S. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J. Personal. 1962, 30, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Mar, R.A.; Peterson, J.B. Psychological entropy: A framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, J. Inventar zur Messung von Ambiguitätstoleranz; Asanger: Bern, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, T. Resilienz: Kritik und Perspektiven. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 2005, 51, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann, K.; Quenzel, G. Lebensphase Jugend. Eine Einführung in die Sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung (13. Aufl.); Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, T.; Holder, H. Developing Survey Measures of Inequality of Autonomy in the UK. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Capability and well-being. In The Quality of Life; Nussbaum, M., Sen, A., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being in adult life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fend, H. Neue Theorie der Schule: Eine Einführung in das Verstehen von Bildungssystemen; VS: Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herreveld, F.; Van Der Pligt, J.; Claassen, L.; Van Dijk, W.W. Inmate Emotion Coping and Psychological and Physical Well-Being: The Use of Crying Over Spilled Milk. Crim. Justice Behav. 2007, 34, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; DeLongis, A.; Gruen, R.J. The dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping and encounter outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: California, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelle, U.; Kluge, S. TypusFallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. In Vom Einzelfall zum; VS: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]