Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about Youth-Initiated Mentoring through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Purpose

3. Section 1: Introduction to YIM and Description of Scoping Review Strategy

3.1. Youth-Initiated Mentoring

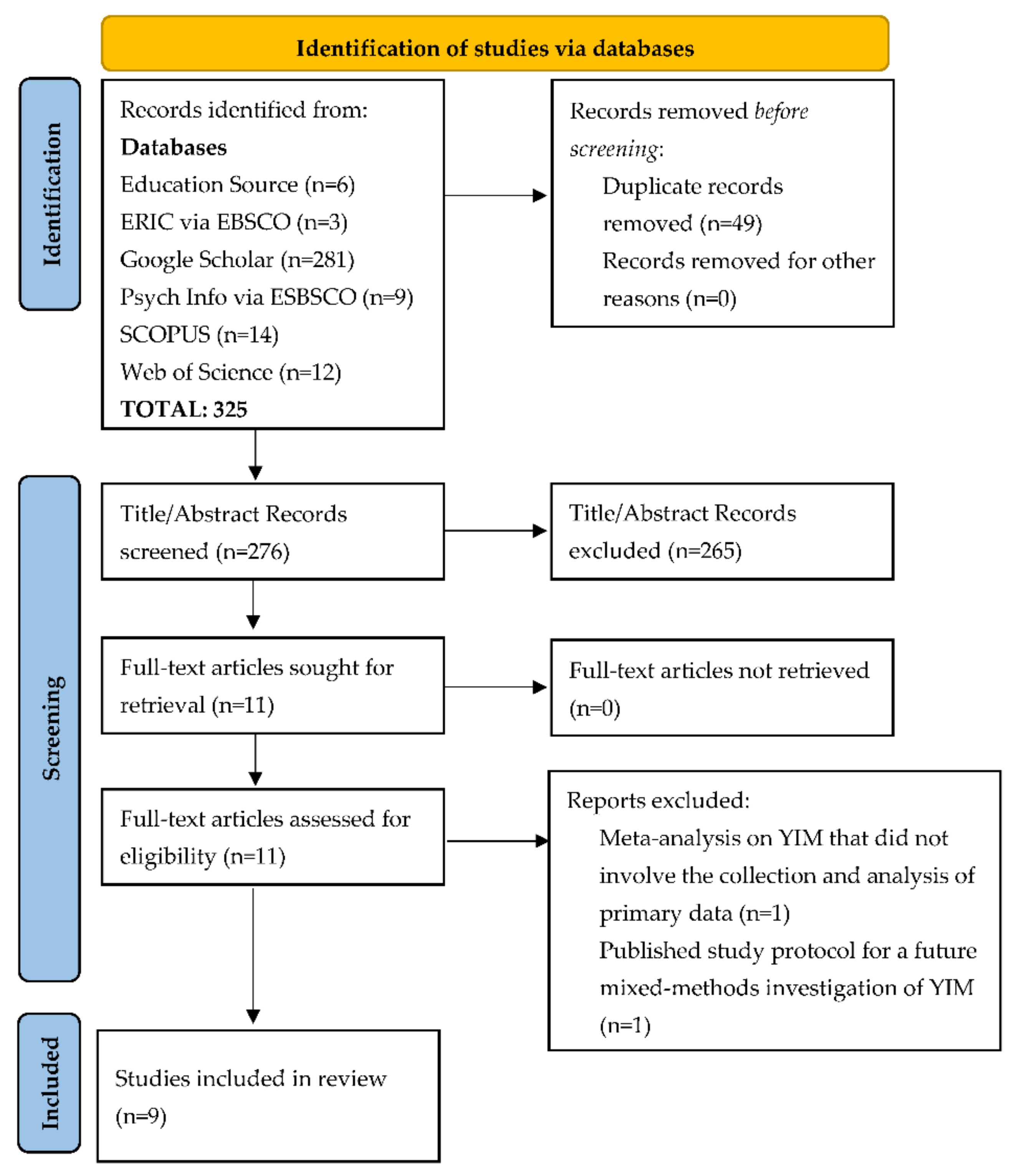

3.2. Search Strategy for Scoping Review

4. Section 2: Findings from the Scoping Review

4.1. Mentor Nomination Process

4.2. Nature and Quality of YIM Relationships

4.3. Relationship Closure

4.4. Youth Outcomes

5. Section 3: Community-Based Participatory Research

6. Community-Based Participatory Research

6.1. Benefits of CBPR

6.2. Considerations and Challenges of CBPR

7. Section 4: Using CBPR to Advance and Mobilize Knowledge about YIM

- CBPR aims to build collaborative and equitable research partnerships.

- CBPR promotes co-learning and capacity-building among all partners and acknowledges and builds on the strengths and resources within communities.

- CBPR is guided by an ecological and multideterminant perspective.

- CBPR strives to create relevant, sustainable, and positive change for communities.

8. Principle #1: CBPR Aims to Build Collaborative and Equitable Research Partnerships

CBPR Principle #1 and YIM: Potential Applications and Benefits

9. Principle #2: CBPR Builds on the Strengths and Resources within Communities and Promotes Co-Learning and Capacity-Building among All Partners

Principle #2 and YIM: Potential Applications and Benefits

10. Principle #3: CBPR Is Guided by an Ecological and Multideterminant Perspective

Principle #3 and YIM: Potential Applications and Benefits

11. Principle #4: CBPR Strives to Create Relevant, Sustainable, and Positive Change for Communities

Principle #4 and YIM: Potential Applications and Benefits

12. Section 5: Key Insights, Considerations, and Conclusions

Key Insights: Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about YIM through CBPR

13. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhodes, J.E. Stand by Me: The risks and Rewards of Mentoring Today’s Youth; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, D.L.; Karcher, M.J. Handbook of Youth Mentoring, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hagler, M.A.; Rhodes, J.E. The Long-Term Impact of Natural Mentoring Relationships: A Counterfactual Analysis. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, K.M.; Hagler, M.A.; Stams, G.-J.; Raposa, E.B.; Burton, S.; Rhodes, J.E. Non-Specific versus Targeted Approaches to Youth Mentoring: A Follow-up Meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D.L.; Holloway, B.E.; Valentine, J.C.; Cooper, H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 157–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, D.L.; Portillo, N.; Rhodes, J.E.; Silverthorn, N.; Valentine, J. How Effective Are Mentoring Programs for Youth? A Systematic Assessment of the Evidence. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2011, 12, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposa, E.B.; Rhodes, J.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Card, N.; Burton, S.; Schwartz, S.; Sykes, L.A.Y.; Kanchewa, S.; Kupersmidt, J.; Hussain, S. The Effects of Youth Mentoring Programs: A Meta-analysis of Outcome Studies. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.E.; Rhodes, J.E. From Treatment to Empowerment: New Approaches to Youth Mentoring. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, L.; Blom, D.; Kara, E.; Assink, M.; Stams, G.J.; Schwartz, S.; Rhodes, J. Youth initiated mentoring: A meta-analytic study of a hybrid approach to youth mentoring. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koper, N.; Creemers, H.E.; van Dam, L.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Branje, S. Needs of Youth and Parents From Multi-Problem Families in the Search for Youth-Initiated Mentors. Youth Soc. 2021, 00, 44–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Rhodes, J.E.; Spencer, R.; Grossman, J.B. Youth Initiated Mentoring: Investigating a New Approach to Working with Vulnerable Adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 52, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.; Drew, A.; Gowdy, G.; Horn, J.P. “A positive guiding hand”: A qualitative examination of youth-initiated mentoring and the promotion of interdependence among foster care youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 93, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Drew, A.L.; Horn, J.P. Program staff perspectives on implementing youth-initiated mentoring with systems-involved youth. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2781–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Gowdy, G.; Drew, A.; Rhodes, J.E. “Who Knows Me the Best and Can Encourage Me the Most?”: Matching and Early Relationship Development in Youth-Initiated Mentoring Relationships with System-Involved Youth. J. Adolesc. Res. 2018, 34, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Tugenberg, T.; Ocean, M.; Schwartz, S.E.; Rhodes, J.E. “Somebody who was on my side”: A qualitative examination of youth initiated mentoring. Youth Soc. 2016, 48, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, L.; Neels, S.; De Winter, M.; Branje, S.; Wijsbroek, S.; Hutschemaekers, G.; Dekker, A.; Sekreve, A.; Zwaanswijk, M.; Wissink, I.; et al. Youth Initiated Mentors: Do They Offer an Alternative for Out-of-Home Placement in Youth Care? Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 1764–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, L.; Bakhuizen, R.E.; Schwartz, S.E.O.; De Winter, M.; Zwaanswijk, M.; Wissink, I.B.; Stams, G.J.J.M. An Exploration of Youth–Parent–Mentor Relationship Dynamics in a Youth-Initiated Mentoring Intervention to Prevent Out-of-Home Placement. Youth Soc. 2019, 51, 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, L.; Heijmans, L.; Stams, G.J. Youth Initiated Mentoring in Social Work: Sustainable Solution for Youth with Complex Needs? Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 38, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Minkler, M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 2018. Available online: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Jacquez, F.; Vaughn, L.M.; Wagner, E. Youth as Partners, Participants or Passive Recipients: A Review of Children and Adolescents in Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; Board, T.L.A.; Straits, K.J.E.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Espinosa, P.R.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balazs, C.L.; Morello-Frosch, R. The three R’s: How community-based participatory research strengthens the rigor, relevance, and reach of science. Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, C.; Raymaker, D.; McDonald, K.; Kapp, S.; Weiner, M.; Ashkenazy, E.; Gerrity, M.; Kripke, C.; Platt, L.; Baggs, A. The development and evaluation of an online healthcare toolkit for autistic adults and their primary care providers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, M.; Ammerman, A.; Eng, E.; Gartlehner, G.; Lohr, K.N.; Griffith, D.; Whitener, L. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Evid. Rep./Technol. Assess. 2004, 99, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches, 1st ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker, S.; Savan, B.; McGrath, M.; Kolenda, B.; Mildenberger, M. ‘If you could change one thing…’What community-based researchers wish they could have done differently. Community Dev. J. 2008, 43, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V. Ethical Challenges in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merves, M.L.; Rodgers, C.R.; Silver, E.J.; Sclafane, J.H.; Bauman, L.J. Engaging and sustaining adolescents in Community-Based Participatory Research: Structuring a youth-friendly CBPR environment. Fam. Community Health 2015, 38, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.; Schulz, A.; Parker, E.; Becker, A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K. Community-Based Participatory Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S.D.; Andrews, J.O.; Magwood, G.S.; Jenkins, C.; Cox, M.J.; Williamson, D.C. Community Advisory Boards in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Synthesis of Best Processes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A70. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon, M.; Murray-Garcia, J. Cultural humility vs. cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in medical education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 1998, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloos, B.; Hill, J.; Thomas, E.; Wandersman, A.; Elias, M.; Dalton, J.H. Community Psychology: Linking Individuals and Communities, 3rd ed.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Langhout, R.D.; Thomas, E. Imagining participatory action research in collaboration with children: An introduction. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 46, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyon, Y.; Bender, K.; Kennedy, H.; Dechants, J. A Systematic review of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, youth outcomes, and future directions. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamrova, D.P.; Cummings, C.E. Participatory action research (PAR) with children and youth: An integrative review of methodology and PAR outcomes for participants, organizations, and communities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Carter, B. Being Participatory: Researching with Children and Young People, Co-Constructing Knowledge Using Creative Techniques; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H. How adults change from facilitating youth participatory action research: Process and outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Listening to and involving young children: A review of research and practice. Early Child Dev. Care 2005, 175, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goelman, H.; Pivik, J.; Guhn, M. New Approaches to Early Child Development: Rules, Rituals, and Realities, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, R.; Basualdo-Monico, A. Family involvement in the youth mentoring process: A focus group study with program staff. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.E.; Overton, B.; Pryce, J.M.; Barry, J.E.; Sutherland, A.; DuBois, D.L. “I really wanted her to have a big sister”: Caregiver perspectives on mentoring for early adolescent girls. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basualdo-Monico, A.; Spencer, R. A parent’s place: Parents’, mentors’ and program staff members’ expectations for and experiences of parental involvement in community based youth mentoring relationships. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 61, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nind, M. Participatory data analysis: A step too far? Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.; Badham, J.; Corepal, R.; O’Neill, R.F.; Tully, M.A.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. Network methods to support user involvement in qualitative data analyses: An introduction to participatory theme elicitation. Trials 2017, 18, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman-MacLaren, M.; Mills, J.; Tommbe, R. Interpretive focus groups: A participatory method for interpreting and extending secondary analysis of qualitative data. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 25214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDavitt, B.; Bogart, L.M.; Mutchler, M.G.; Wagner, G.J.; Green, H.D.; Lawrence, S.J.; Mutepfa, K.D.; Nogg, K.A. Dissemination as Dialogue: Building Trust and Sharing Research Findings Through Community Engagement. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, A.; Greenwood, K.E.; Williams, S.; Wykes, T.; Rose, D.S. Hearing the voices of service user researchers in collaborative qualitative data analysis: The case for multiple coding. Health Expect. 2013, 16, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the positive youth project. Health Educ. Behav. 2008, 35, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference and Country of Origin | Research Context | Aim of Study | Participants | Methods | Design | Data Type | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koper et al. (2021); Netherlands; [13] | YIM as an alternative to out-of-home care | Document what youth and parents look for in their mentors and what mentors believe they offer to families. | Youth (N = 15) (13–18 years of age) (M = 15.67, SD = 1.70) Mentors (N = 8) (22–69 years of age) (M = 41.30, SD = 17.15) Parents (N = 13) (36–50 years of age) (M = 43.76, SD = 4.64) | Qualitative | Exploratory | Interviews | Thematic Analysis |

| Schwartz et al. 2013; United States; [14] | Educational Residential Program | Explore the benefits of YIM for youth participating in an intensive residential intervention program. | Youth (N = 1,173) (16–18 years of age) | Mixed | Explanatory | Follow-up surveys; Retrospective interviews (n = 30) | Ordinary least square regression, Thematic Analysis |

| Spencer et al. (2018); United States; [15] | Transition from Foster-Care | Examine experiences of YIM relationships among youth transitioning out of the foster care system. | Youth (N = 12) (16–25 years of age) (M = 19.17, SD = 2.59) Mentors (N = 9) (21–56 years of age) (M = 34.78, SD = 10.15) | Qualitative | Case-Study | In-depth semi-structured interviews | Thematic Analysis |

| Spencer et al. (2021); United States; [16] | Mentoring Organizational Level | Explore staff motivation to implement YIM and identify facilitators and barriers to success. | Mentoring Program Staff (N = 11) (26–47 years of age) (M = 32.10, SD = 7.58) | Qualitative | Case Study | In-depth semi-structured interviews | Thematic Analysi |

| Spencer et al. (2018); United States; [17] | Transition from Foster-Care | Examine the formation of YIM relationships and how they are experienced by youth, mentors, and parents. | Youth (N = 17) (15–25 years of age) (M = 18.38, SD = 2.70) Mentors (N = 14) (21–58 years of age) (M = 38.00, SD = 10.71) Parents (N = 6) (29–47 years of age) (M = 37.83, SD = 6.74) | Qualitative | Case Study | In-depth interviews | Thematic Analysis |

| Spencer et al. (2016); United States; [18] | Educational Residential Program | Explore the mentor selection process, role of YIM relationships, and their impact. | Youth (N = 30) (20–23 years of age) | Qualitative | Explanatory | Retrospective interviews | Thematic Analysis |

| van Dam et al. (2017); Netherlands; [19] | Outpatient Care | Examine whether YIM offers a promising alternative to out-of-home-care. | Youth (N = 96) (11–19 years of age) (M = 15.40, SD = 1.81) | Quantitative | Case Study | Standardized survey | Case-file analyses; Chi-square analysis |

| van Dam et al. (2019); Netherlands; [20] | YIM as alternative to out-of-home care | Explore the mentor-nomination process and sustainability. | Youth (N = 6) (15–18 years of age) (M = 16.30, SD = 1.21) Mentors (N = 6) (28–55 years of age) (M = 41.80, SD = 9.30) Parents (N = 7) (42–62 years of age) (M = 51.30, SD = 6.00) | Qualitative | Explanatory | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic Analysis |

| van Dam et al. (2021); Netherlands; [21] | YIM as alternative to out-of-home care | Examine the long-term impact of YIM relationships. | Mentors (N = 24) (23–78 years of age) (M = 50.00, SD = 13.70) | Qualitative | Case-Study | Semi-structured interviews | Inductive, Axial, and Selective Coding |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dantzer, B.; Perry, N.E. Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about Youth-Initiated Mentoring through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review. Youth 2022, 2, 587-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040042

Dantzer B, Perry NE. Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about Youth-Initiated Mentoring through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review. Youth. 2022; 2(4):587-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleDantzer, Ben, and Nancy E. Perry. 2022. "Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about Youth-Initiated Mentoring through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review" Youth 2, no. 4: 587-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040042

APA StyleDantzer, B., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Advancing and Mobilizing Knowledge about Youth-Initiated Mentoring through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review. Youth, 2(4), 587-609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040042