Addressing Hostile Attitudes in and through Education—Transformative Ideas from Finnish Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Hostile Attitudes

1.2. Finnish Education and the Problem of Normative Finnishness

1.3. Educational Programs to Foster Peace

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis

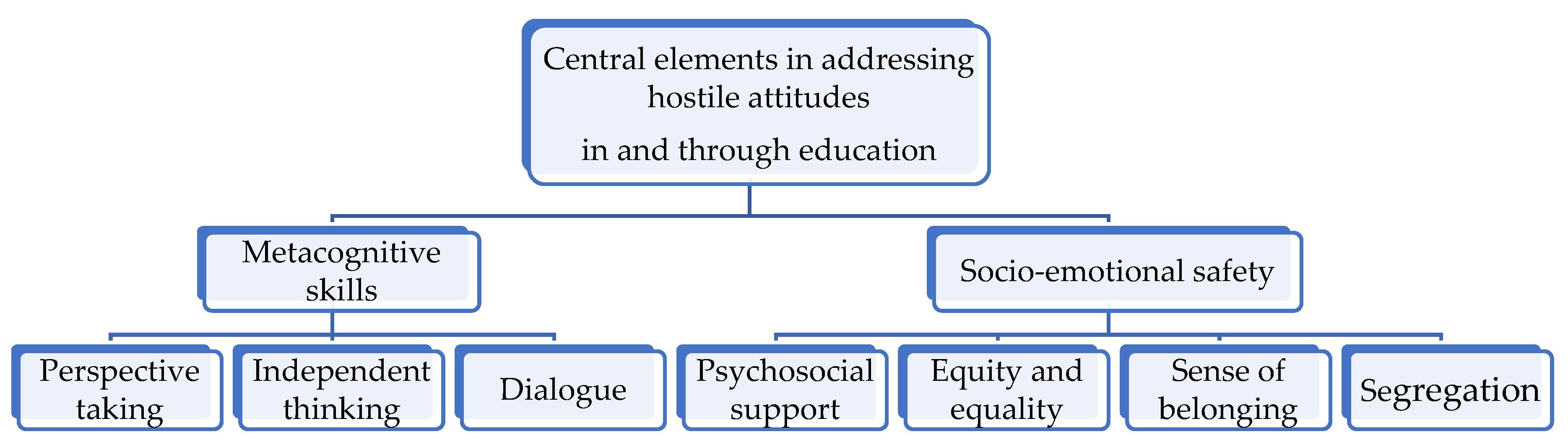

3. Results

3.1. Metacognitive Skills

It is [central] to offer instruction and knowledge to everyone about different topics, so that people could form their views and opinions based on facts and not on prejudices.

[It is important] to discuss how little individuals can impact premises of their lives. And how vulnerable to influences the human mind is. And somehow bring forth the fact that things are never black and white.

The history we learn at school is very white and European. The worldviews of students would certainly become broader, if history was taught from the African perspective, for example, before the arrival of the imperialists, or from the Asian perspective, for example.

[It is important] to accentuate that many things grow massively out of proportions in social media because people overreact and seek for drama.

[We need to] figure out the pitfalls of algorithms. So, if I watch one right-wing-endorsing video on YouTube, it will propose more content like that.

[It is important] to teach criticality towards one’s own culture and customs, to broaden one’s thinking skills.

[Schools should] encourage people to be critical, in a healthy way, towards others’ and especially towards one’s own ideas.

In my view, it would be central to bring everyone together to discuss different perspectives in a neutral and objective way, after which everyone could calmly choose the most fitting perspective and ideology for themselves, without pressure from the others.

Discussion means exchanging thoughts and ideas, learning and teaching about different perspectives. It is not about knocking down the opponent and his views.

3.2. Socio-Emotional Safety

The only method to eliminate hate speech and racism with little resources is the educators’ own example of tolerance toward other people, cultures, values, and attitudes.

It is critically important for teachers not to teach according to their own political convictions. Or at least they have to give a disclaimer before making a political statement to the students.

Youths’ mental health problems should be recognized better and prevented earlier. It would be helpful to have an easier access to the school psychologist. Also, if the class sizes were smaller, teachers would have an opportunity to get to know their students and notice their mental health problems, and the development of hostile attitudes, in time.

Schools should be more vocal about the importance of wellbeing. [They could] organize moments of relaxation and give less homework, and emphasize that students should also have time to sleep. This conveys a feeling to the students that they are genuinely cared for, and that academic performance is not prioritized [over wellbeing].

[Schools should] increase the sense of belonging by urging different people to talk to each other and by encouraging shyer people to speak up, too.

A considerate and open-minded atmosphere [at school] can be created by talking about different human destinies and lived experiences.

Hostile attitudes are often due to the feeling of not being accepted and of not belonging to any group.

[Schools should] kick out the bullying, violent, and troublemaking immigrant students. They disturb the schooling of others.

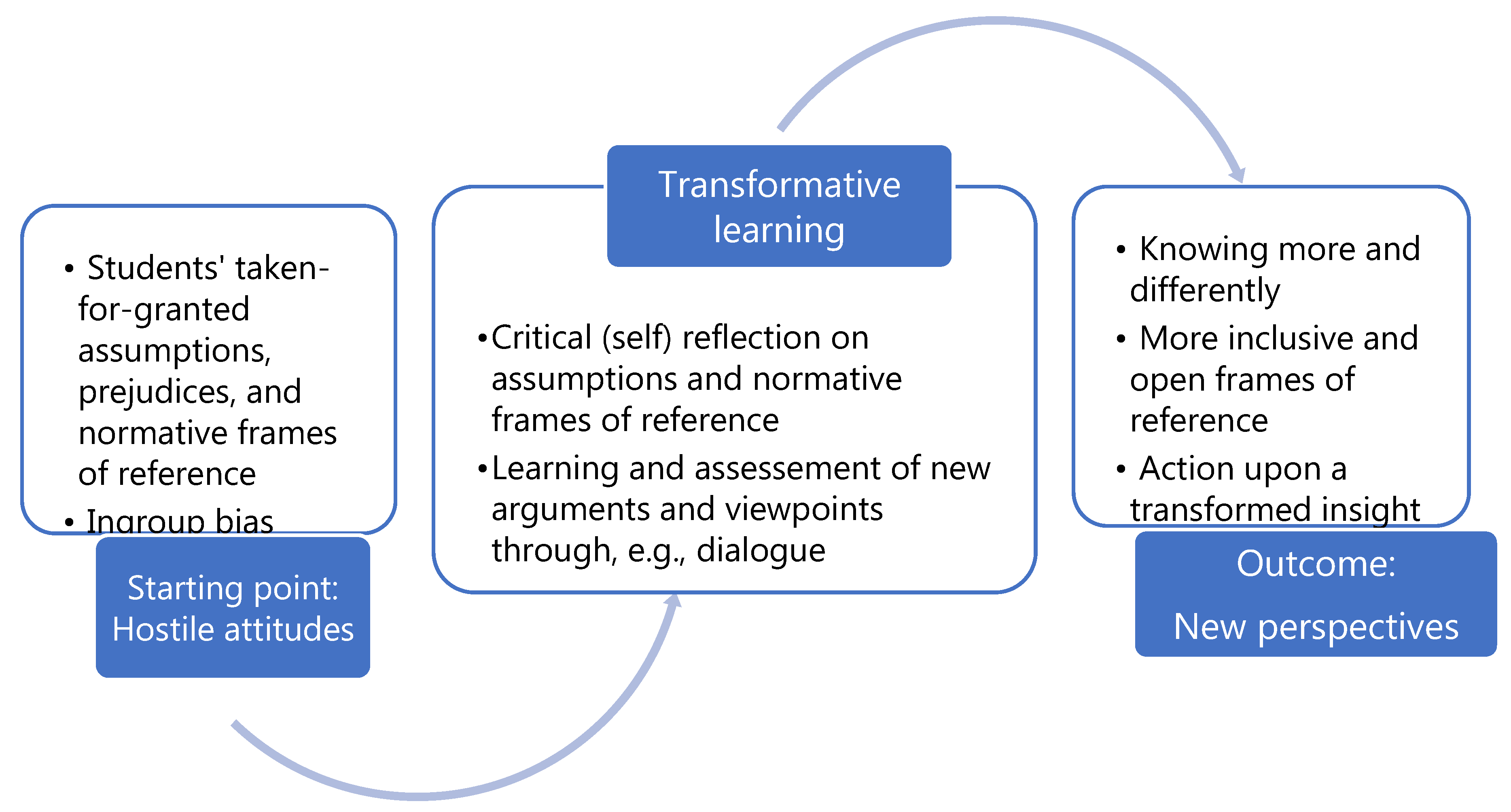

4. Discussion

Transformative Learning in the Creation of More Peaceful Societies

5. Conclusive Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niemi, P.-M.; Kimanen, A.; Kallioniemi, A. Including or excluding religion and worldviews in schools? Finnish teachers’ and teacher students’ perceptions. J. Beliefs Values 2019, 41, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekkonen, A.; Ylä-Anttila, T. Affective blocs: Understanding affective polarization in multiparty systems. Elect. Stud. 2021, 72, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Varennes, F. Recommendations Made by the Forum on Minority Issues at Its Thirteenth Session on the Theme “Hate Speech, Social Media and Minorities”; Human Rights Council, United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sakki, I.; Martikainen, J. Mobilizing collective hatred through humour: Affective–discursive production and reception of populist rhetoric. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 60, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallinkoski, K.; Koirikivi, P.-M.; Malkki, L. ‘What is this ISIS all about?’ Addressing violent extremism with students: Finnish educators’ perspectives. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 21, 778–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.M. Extremism, Kindle ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. Schooling and the Struggle for Public Life: Democracy’s Promise and Education’s Challenge; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bynner, J.; Chisholm, L.; Furlong, A. (Eds.) Youth, Citizenship and Social Change in a European Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love and Outgroup Hate? J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, B.M.; Mania, E.W.; Gaertner, S.L. Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, W.H.; Sherif, M.; Sherif, C.W. The adolescent in his group in its setting. Problems of Youth: Transition to Adulthood in a Changing World. Soc. Forces 1967, 45, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beelmann, A.; Heinemann, K.S. Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 35, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNAE. Finnish Education in a Nutshell. Finnish National Agency for Education. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/finnish_education_in_a_nutshell.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- NCCBE. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. Finnish National Agency for Education. Finnish Education in a Nutshell. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/finnish-education-nutshell (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Hughes, C. Addressing violence in education: From policy to practice. Prospects 2020, 48, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessel, A. Prejudice in Schools: Promotion of an Inclusive Culture and Climate. Educ. Urban Soc. 2010, 42, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, S.; Lahelma, E. Subtle discourses on equality in the Finnish curricula of upper secondary education: Reflections of the imagined society. J. Curric. Stud. 2015, 48, 650–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action. Volume 1: Reason and the Realization of Society; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P.; Ramos, M.B. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- FRA. Being Black in the EU Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2019-being-black-in-the-eu-summary_en.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Ahmad, A. When the Name Matters: An Experimental Investigation of Ethnic Discrimination in the Finnish Labor Market. Sociol. Inq. 2020, 90, 468–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juva, I. Who Can Be ‘Normal’? Constructions of Normality and Processes of Exclusion in Two Finnish Comprehensive Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2019. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/306212/Whocanbe.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Edström, C.; Brunila, K. Troubling gender equality: Revisiting gender equality work in the famous Nordic model countries. Educ. Chang. 2016, 20, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaran, J.I.; Lehtonen, J. Windows of opportunities: Nordic perspectives on sexual diversity in education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A.; Matemba, Y.; Benjamin, S.; Du Preez, P.; Koirikivi, P.; Simmonds, S. Decolonising the religious education curriculum. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2021, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, E. Critiquing coloniality, ‘epistemic violence’ and western hegemony in comparative education—The dangers of ahistoricism and positionality. Comp. Educ. 2020, 56, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikander. P. Colonialist “discoveries” in Finnish school textbooks. Nord. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2015, 4, 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. The changing pedagogies of space: Representation of the other in Finnish School geography textbooks. In Text and Image: Social Construction of Regional Knowledges; Brunn, S.D., Buttimer, A., Wardenga, U., Eds.; Institut für Länderkunde: Leipzig, Germany, 2011; pp. 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, R.B.; Stadius, P.; Stark, E. Core Citizens, Imagined Nation: Historical Security Practices of the Majority and Strategies of the Minorities in Finland; An Introduction to the Issue. J. Finn. Stud. 2021, 24, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sakki, I.; Hakoköngäs, E.; Pettersson, K. Past and Present Nationalist Political Rhetoric in Finland: Changes and Continuities. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 37, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F.; Itkonen, T. Introduction. In Silent Partners in Multicultural Education; Itkonen, T., Dervin, F., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017; pp. xi–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Mikander, P. Western values under threat? Perceptions of “us” and “them” in history textbooks in Finnish schools. In Binaries in Battle: Representations of Division and Conflict; Vuorinen, M., Kotilainen, N., Huhtinen, A.M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014; pp. 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Helkama, K.; Portman, A. Protestant Roots of Honesty and Other Finnish Values. In On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland Societal Perspectives; Sinnemäki, K., Portman, A., Tilli, N.R.H., Eds.; Finnish Literature Society: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, H.; Sinnemäki, K. The Role of Lutheran Values in the Success of the Finnish Educational System. In On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland Societal Perspectives; Sinnemäki, K., Portman, A., Tilli, N.R.H., Eds.; Finnish Literature Society: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; pp. 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen, S.; Nylund, M.; Rosvall, P. Imagining societies through discourses on educational equality: A cross-cultural analysis of Finnish and Swedish upper secondary curricula from 1970 to the 2010s. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 18, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helkama, K.; Salminen, S.; Uutela, A. A world at peace as a personal value in Finland: Its relationship to demographic characteristic, political identification, and type of moral reasoning. Curr. Res. Peace Violence 1987, 10, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, S.; Koirikivi, P.; Salonen, V.; Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A. Safeguarding social justice and equality: Exploring Finnish youths’ “Intergroup Mindsets” as a novel approach in the prevention of radicalization and extremism through education. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Koirikivi, P.; Benjamin, S.; Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. Values, lifestyles, and narratives of prejudices amongst Finnish youth. J. Beliefs Values 2021, 42, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Elliott, K.; Namdar, C.; Koirikivi, P.; Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A. Young Finns and the Logics of Othering. In review.

- Lauronen, T. Upper Secondary School Student Barometer 2022. The Union of Upper Secondary School Students in Finland. Available online: https://lukio.fi/lukiolaisbarometri/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Kiilakoski, T. (Ed.) Kestävää Tekoa. Nuorisobarometri 2021 [Youth Barometer]. Available online: https://tietoanuorista.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FI-Infografiikka-Nuorisobarometri-2021.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Noddings, N. Peace Education. How We Come to Love and Hate War; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sant, E. Democratic Education: A Theoretical Review (2006–2017). Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 655–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristol, D.; Mitchell, R.; Gimbert, B. Citizenship Education: A Historical Perspective (1951–Present). Action Teach. Educ. 2010, 32, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Multicultural education and global citizens. In The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity; Benet-Martínez, V., Hong, Y.-Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, N. The Human Rights Education Handbook: Effective Practices for Learning, Action, and Change. Human Rights Education Series, Topic Book; Human Rights Resource Center, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, D.; Rosen, Y.; Nets-Zehngu, R. Peace Education in Societies Involved in Intractable Conflicts; Salomon, G., Edward Cairns, E., Eds.; Handbook on Peace Education; Routledge Handbooks Online: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alemanji, A.A. (Ed.) Antiracism Education in and Out of Schools; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mikander, P.; Zilliacus, H.; Holm, G. Intercultural education in transition: Nordic perspectives. Educ. Inc. 2018, 9, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummelstedt, I. Acknowledging Diversity but Reproducing the Other: A Critical Analysis of Finnish Multicultural Education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Veugelers, W. Different Ways of Teaching Values. Educ. Rev. 2000, 52, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiäinen, T.; Poulter, S. Finnish teachers’ approaches to personal worldview expressions: A question of professional autonomy and ethics. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2021, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallinkoski, K.; Benjamin, S. From playground extremism to neo-Nazi ideology—Finnish educators’ perceptions of violent radicalisation and extremism in educational institutions. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2022, in press.

- Zembylas, M. Pedagogies of strategic empathy: Navigating through the emotional complexities of anti-racism in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2012, 17, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. International Commission on the Futures of Education. Unesco Report. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379381 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Mezirow, J. An overview on transformative learning. In Contemporary Theories of Learning; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Finland. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/index_en.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maynes, J. Critical Thinking and Cognitive Bias. Informal Log. 2015, 35, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Koirikivi, P.; Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A. States of Mind: Peace Education and Preventing Violent Extremism. In Peace Education and Religions: Perspectives, Pedagogy, Policies; Hermansen, M., Aslan, E., Akkılıç, E.E., Eds.; Wiener Beiträge zur Islamforschung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.E.; Baelen, R.N.; Yu, A. Actively open-minded thinking in American adolescents. Rev. Educ. 2020, 8, 768–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T. Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme 2019, 17, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, J.L. Rethinking the Role of Ideology in Mass Atrocities. Terror. Politi Violence 2014, 26, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, G.H.; Chen, T.; Leung, K. Team creativity/innovation in culturally diverse teams: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, C.; Johansson, T. The hateful other: Neo-Nazis in school and teachers’ strategies for handling racism. Br. J. Social. Educ. 2020, 41, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Salonen, V.; Gearon, L.; Koirikivi, P.; Kuusisto, A. Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosvall, P.; Ohrn, E. Teachers’ silences about racist attitudes and students’ desires to address these attitudes. Intercult. Educ. 2014, 25, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L. Interrupting Extremism by Creating Educative Turbulence. Curric. Inq. 2014, 44, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C. (Ed.) A social justice and human rights education project: A search for caring and safe spaces. In Safe Spaces. Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro, A.; August, G.; Kennedy, M.S.; Newman, B.M. Safe Spaces: Making Schools and Communities Welcoming to LGBT Youth; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Flensner, K.K.; Von der Lippe, M. Being safe from what and safe for whom? A critical discussion of the conceptual metaphor of ‘safe space’. Intercult. Educ. 2019, 30, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, K.C. The importance of safe space and student voice in schools that serve minoritized learners. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 2015, 30, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, L.I. “I Didn’t Have the Language”: Young People Learning to Challenge Gender-Based Violence through Consumption of Social Media. Youth 2022, 2, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Cowell, J.M. The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté-Lussier, C.; Fitzpatrick, C. Feelings of Safety at School, Socioemotional Functioning, and Classroom Engagement. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, B. Is “Safety” Dangerous? A Critical Examination of the Classroom as Safe Space. Can. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 2010, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpviken, A.N. Psychological Vulnerabilities and Extremism among Western Youth: A Literature Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirikivi, P.; Benjamin, S.; Hietajärvi, L.; Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. Resourcing resilience: Educational considerations for supporting well-being and preventing violent extremism amongst Finnish youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M. Resilience to violent extremism and terrorism. A multisystemic analysis. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change; Ungar, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Meehan, C.; Farquharson, J. The solace of radicalism: Self-uncertainty and group identification in the face of threat. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, P.-M. Students’ experiences of social integration in schoolwide activities—An investigation in the Finnish context. Educ. Inc. 2018, 8, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benjamin, S.; Alemanji, A. “That Makes Us Very Unique”: A Closer Look at the Institutional Habitus of Two International Schools in Finland and France. In Silent Partners in Multicultural Education; Itkonen, T., Dervin, F., Eds.; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Huilla, H. Kaupunkikoulut ja Huono-Osaisuus [Disadvantaged Urban Schools]. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G.; Coşkun, M. Student subjective wellbeing, school functioning, and psychological adjustment in high school adolescents: A latent variable analysis. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 4, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Upadhyaya, K. School engagement and school burnout profiles during high school—The role of socio-emotional skills. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 17, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegan, R. What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. In Contemporary Theories of Learning; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cassam, Q. Vices of the Mind: From the Intellectual to the Political; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Kreijkes, P.; Salmela-Aro, K. Students’ growth mindset: Relation to teacher beliefs, teaching practices, and school climate. Learn. Instr. 2022, 80, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osher, D.; Sprague, J.; Weissberg, R.P.; Axelrod, J.; Keenan, S.; Kendziora, K.; Zins, J.E. A comprehensive approach to promoting social, emotional, and academic growth in contemporary schools. Best Pract. Sch. Psychol. 2007, 5, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Perspective Transformation. Adult Educ. Q. 1978, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 74, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Embedding Values and Attitudes in Curriculum. Shaping a Better Future. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/embedding-values-and-attitudes-in-curriculum_aee2adcd-en (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Fornaciari, A.; Rautiainen, M. Finnish teachers as civic educators: From vision to action. Citizsh. Teach. Learn. 2020, 15, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benjamin, S.; Koirikivi, P.; Gearon, L.F.; Kuusisto, A. Addressing Hostile Attitudes in and through Education—Transformative Ideas from Finnish Youth. Youth 2022, 2, 556-569. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040040

Benjamin S, Koirikivi P, Gearon LF, Kuusisto A. Addressing Hostile Attitudes in and through Education—Transformative Ideas from Finnish Youth. Youth. 2022; 2(4):556-569. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040040

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenjamin, Saija, Pia Koirikivi, Liam Francis Gearon, and Arniika Kuusisto. 2022. "Addressing Hostile Attitudes in and through Education—Transformative Ideas from Finnish Youth" Youth 2, no. 4: 556-569. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040040

APA StyleBenjamin, S., Koirikivi, P., Gearon, L. F., & Kuusisto, A. (2022). Addressing Hostile Attitudes in and through Education—Transformative Ideas from Finnish Youth. Youth, 2(4), 556-569. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2040040