Abstract

Youth with disabilities have a higher risk of experiencing mental health problems than their non-disabled peers. In part, this results from their social exclusion and dearth of social networks. An intervention informed by positive psychology principles and peer mentoring approaches was developed and evaluated with 12 youths with disabilities who had musical interests and talents as musicians. It included the real-world experience of applying the training in a school-based music project with over 200 typically developing pupils aged nine years in four schools. Evaluation data were obtained from project staff, self-ratings by the mentors and through group interviews with them, as well as from reactions of school pupils and interviews with six teachers. The study confirmed the benefit of music and peer mentoring as a means of promoting the self-esteem and self-confidence of youth with disabilities. Further research is needed to determine the longer-term mental health benefits musically based interventions can offer to youth with disabilities and, more generally, to young children in schools.

1. Introduction

The incidence of mental health difficulties is much higher in persons with disabilities than in their non-disabled peers. These emerge in childhood and become more marked for youth aged 15 to 24 years and for older adults. Recently published literature reviews document the nature and type of difficulties experienced by persons with autism [1], intellectual disabilities [2] and those with physical impairments and chronic illnesses [3], such as depression, anxiety conditions, attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD), depression and oppositional defiant disorders [4]. Consequently, higher proportions of persons with these disabilities are prescribed medications compared to their non-disabled peers [5,6].

Yet, mental ill-health is not due to their impairments per se, but rather from the social and psychological impacts that they experience as persons with disabilities [7]. Although social and environmental factors may also contribute to poor mental health and wellbeing in non-disabled persons, the risk is heightened in youth and adults with disabilities because of the well-attested social exclusion that they experience, compounded by their typically reduced social networks and comparative lack of friendships [8,9].

Various theoretical frameworks have been proposed to understand the relationships between social factors and mental wellbeing. With youth, in particular, the focus has been on concepts such as poor self-esteem and low self-confidence, resulting in reduced self-efficacy and social motivation to engage with others [10]. Hence, the focus of interventions to promote better mental health—particularly from a preventative perspective—has been on the provision of social support. A recent review of such studies with autistic adults suggests that increased employment opportunities and social skills training seem to be the most effective, although the provision of wider community supports remains limited and unevaluated [11]. A further review of interventions aimed at youth with long-term physical health conditions [12] identified the need for “environments that allows young people to share their experiences and build empathetic relationships, (that) can enable participants to access social support and increase feelings of hope and empowerment” p. 832.

To date, much of the focus with disabled youth has been on remediating their assessed cognitive and/or social deficits. By contrast, in mainstream youth programmes, the focus has shifted from remediation toward positive youth development [13], which is reflective of Sigelman’s conception of positive psychology and the interventions he argues are needed to build mental wellbeing and personal growth, such as positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment [14]. A scoping review of the theory and practice of positive youth development identified seven programme formats including sports, art, music, mentoring and school-based programmes [15]. More broadly, the World Health Organisation concluded from a major review of over 900 studies that the arts in diverse forms can potentially impact both mental and physical health [16].

Recent studies of music-based intervention activities aimed at fostering the well-being of adolescents identified three contributions: Namely, music-based activities were a catalyst for relationship building, a means for self-expression and a resource for self-transformation and thereby built participants’ basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy [17,18]. However, none of the studies seem to have included disabled youth.

Peer mentoring has also received increased attention in boosting the mental well-being of youth [19]. Thus far, there is limited literature on mentor outcomes but there is some evidence that young mentors can be effective in providing positive mentoring to their peers [20] including a study undertaken with learning-disabled youth [21].

It was against this background that the present study was conceived. It took the form of an action-research project, in which disabled youth were trained to act as music mentors to primary-school pupils using a group-based approach [22]. The research questions posed were to determine if the self-esteem of the mentors was enhanced through training and the ‘real-world’ experience of mentoring, while also introducing the school pupils to music-making with young musicians with disabilities. In due course, music, as well as other arts-based interventions, may have a role in boosting the resilience of younger children to mental health problems [23].

Study Aims

The aims of the study were:

- To develop a training programme through group-based music mentoring for youth with disabilities.

- To evaluate the impact of the programme on youth with disabilities with respect to their self-esteem and efficacy as musicians.

- To determine the reactions of school pupils and teachers to the young music mentors with disabilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Music Mentors

The project aimed to recruit a cohort of disabled young adults aged 18 and over (“Music Mentors”), who would possess a sufficient level of musical ability that would be beyond that of most primary school children with whom they would be working and/or the social skills that could, with training, allow them to hold children’s attention within a music class.

In total, 22 persons were recruited, none of whom had diagnosed or self-declared mental health difficulties. Two persons came through a local special school, two as a result of direct contact with their parents and the remaining eighteen through the project staff’s awareness of their existing ability as musicians enrolled within other disability-focused charities in the city. However, eight persons did not complete the programme mainly due to the difficulty they encountered with training, their reluctance to perform or speak in front of others or their unsuitability for a mentorship role. Furthermore, two others left soon after the project commenced.

Of the 12 remaining Music Mentors, seven were female and five were male, with ages ranging from 19 to 28 years. They had a variety of impairments with some co-occurring: six were on the Autism Spectrum and six had learning disabilities, two had Cerebral Palsy, one had Spinal Bifida and one had Down Syndrome. Six had attended special schools and six had attended mainstream schools. Their chosen musical specialisms were singing (n = 6), percussion (n = 5), dance (n = 3) and song writing (n = 1).

2.2. Music Mentor Training

The overall context of the intervention, called ‘Project Sparks’, was created by two freelance music teachers (referred to as ‘project staff’) as a means of promoting the artistic and musical talents of young people with disabilities and challenge the expectations of society regarding their capabilities.

The musical and performance skills of the Music Mentors were honed through training and peer support over a 12-month period followed by a further two years of working on school-based music projects. Between 6 and 9 h of in-person training was provided per week, supplemented by online peer-to-peer support between Music Mentors through a monitored private Facebook group, which the young adults used to submit “progress vlogs” and feedback as well as organised video calls. A ‘mentoring pyramid’ was devised to help scaffold the young adults’ development and provide them with a sense of achievement during their participation in training [24]. Within this conceptual frame, one constituent skill associated with the mentoring process was given primary focus, and the mentors ‘levelled up’ to the next skill once they had successfully demonstrated its mastery.

From the base of the pyramid upward, the skills included the ability to:

- Make Connections: Gaining rapport with children by showing an interest in their hobbies and finding social commonalities. For some mentors, this process came naturally, whereas, for some of those on the autism spectrum, they benefitted from being equipped with question starters, such as “what is your favourite…”, or “would you rather…”.

- Praise: Finding specific elements of children’s musical performances and conveying them in an authentic way, without sounding repetitive. The mentors were encouraged to notice and acknowledge small details in children’s performances, such as their choice of notes in a melody or the unique way they might hit a drum.

- Demonstrate: The mentors’ ability to convincingly perform the musical material required for all activities on their specialist instrument, voice or dance.

- Explain: The mentors’ ability to instruct children on a task’s learning outcome and clearly outline its associated success criteria.

- Spot the Weaknesses: Ability to explain the errors in a pupil’s performance, e.g., out of time, out of tune.

- Fix the Weaknesses: Ability to target the weakness and guide the pupil to repair errors with continuous feedback and encouragement.

The mentoring pyramid was adjusted depending on each Music Mentor’s learning needs and personality. For those less musically able, they took a role that leveraged their interpersonal skills or vice-versa.

Different methods were used at all stages of the mentoring pyramid, which past research had shown to be effective.

- Role Play: Mentors were individually tasked with facilitating classroom activities within hypothetical teaching scenarios that they were likely to encounter in their work with children. Within these roleplay scenarios, project staff and the other mentors would perform and compose to a similar level of competency as a primary school pupil, which included making mistakes and expressing confusion. These instances gave mentors practice in facilitating learning by asking questions, repairing musical errors and extracting creative ideas.

- Modelling: These tasks were normally prefaced with exemplars by project staff so that mentors were clear on what success looked like before engaging in the role play. The role-play could be differentiated according to the ability of the peer mentor engaged in the task, by presenting them with more or less complex teaching challenges to solve, providing them with opportunities to demonstrate flexibility and persistence in their mentoring.

- Review: Each task could be ‘paused’ and ‘rewound’ so that mentors could trial different instructional approaches and ask for support when needed. At the end of each role-play, the mentors who were acting as pupils would give the facilitating mentor feedback, which was mediated by the project staff.

- Video Analysis: Within small groups, the peer mentors would review video footage of real-life music activities being conducted with children. The mentors were asked to examine the explanations, demonstrations and feedback employed by the instructor on the video, and then evaluate the comparative success or limitations of each instructional decision. The mentors were then encouraged to ‘replay’ these scenarios through role-play, after which they reflected on what they could assimilate into their own practices.

- Practice Teaching Sessions: At regular intervals within their training, the mentors were tasked with mentoring small groups of pupils within a low-stakes environment, in which the children were made aware that the mentors were currently engaged in a training programme and were briefed on how to give supportive feedback to support the mentors’ development. These practice sessions were eventually termed “mistakes labs” by the mentors, which captured the attitude encouraged within the training programme, wherein failure is viewed as a natural consequence of learning.

- Disability Awareness Training: The mentor training also piloted approaches to equip the mentors with an ability to stimulate children’s curiosity about the mentors’ impairments. While the mentors expressed a desire to share their experiences of growing up as disabled musicians, they initially struggled to convey their sentiments in a structured way. After trialling several approaches, the project staff found it optimal to support the mentors in writing and producing scripted video tutorials to teach children about specific disabilities, which were followed by informal question and answer discussions.

2.3. Mentoring School Children

Funding was obtained from a charitable foundation to undertake music sessions for children attending four primary schools in a city in Northern Ireland. The funding aimed to improve economically disadvantaged children’s access to opportunities for creative and participatory music-making. As such, the following inclusion criteria determined schools’ suitability for participation in the project:

- High instances of free school meals (40%).

- Low numbers of pupils playing instruments (10% or less).

- Few resources, lack of music provision according to teaching staff.

- High level of commitment to the time associated with the partnership from principals and teaching staff.

Whilst all four schools were predominantly attended by non-disabled children, the proportion of their pupils with special educational needs ranged from 16% to 33.2%.

None of the schools reported any previous creative music-making involving composition. Music featured mainly around preparation for religious festivals.

The music sessions provided by Project Sparks had the dual aims of increasing the children’s participation and facility in music-making, but also nurturing more inclusive beliefs toward disability and social diversity in general. The latter aspect is reported more fully in an accompanying paper [25].

Eight classes of nine- to ten-year-old pupils took part, involving approximately 200 pupils in total. Each class received 16 h of music sessions, although a portion of the classes was modified due to COVID-19 restrictions. Some were held in their school, others in a performance space available for the project and for one class, the sessions were delivered remotely via the internet.

The lessons developed pupils’ foundational understanding of music through a range of guided-discovery-based activities that cumulatively introduced them to six of the ‘building-blocks’ of music (rhythm, tempo, melody, harmony, texture and timbre) using xylophones, djembes, ukuleles, physical movement and voice. Pupils’ exploration of each of the ‘building-blocks’ developed their creative, aural and motor skills as they worked together to compose short pieces of music and appraise one another’s creative ideas.

The music mentors’ roles involved:

- Outlining the learning outcomes associated with each classroom activity.

- Role-modelling success in music composition and performance.

- Facilitating group work with pupils to advance their experimentations with the musical building-blocks and foster sharing of ideas.

- Providing pupils with praise and constructive feedback to improve their compositions.

- Answering questions about their disability during discussions.

Further details of the music sessions in schools are provided in an accompanying paper [26].

2.4. Evaluation

A mix of quantitative and qualitative data was collected from various informants in order to increase the rigour of the findings through triangulation from different data sources [27].

2.4.1. Music Mentors

The project staff rated the mentors at the start and end of their training using a specially devised scale to assess their teaching and musical competence. Teaching competence was measured according to CCEA Key Stage 3 Communication Statutory Requirements [28] and musical ability was measured according to the Trinity College of Music Group Performance Certificate [29]. Further details of these ratings are provided in the results section.

During the training phase, the mentors completed a monthly Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [30]. This 10-item scale is commonly used and has good internal and test–retest reliability. They also completed a musical self-efficacy scale [31] for both musical knowledge and performing, which also had reasonable psychometric properties.

In addition, four focus group discussions were held with small groups of mentors, which were facilitated by university staff who were uninvolved with the project. Thematic content analyses were undertaken from written transcripts of the sessions [32].

2.4.2. Pupils

The pupils were invited to rate the mentors in terms of their perceptions of them as teachers using computer-based questionnaires, which pupils self-completed or with assistance in reading the items from a teaching assistant. These ratings were obtained before and after their participation in the project. Further details are given in the results section.

2.4.3. Teachers

Telephone interviews were conducted with the class teachers and two of the head-teachers at the participating schools. These were undertaken by the third author who had no involvement with the music lessons. Written transcripts were composed of the interviews conducted after the project’s completion (totalling 91 min). Codes were first assigned to the teachers’ comments by the third author, and these were then grouped by themes that were revised to ensure that all relevant comments had been included. These were then validated by project staff (the first and second authors) who had previously held debriefing sessions with the teachers after each session with their pupils with records kept of the feedback received.

3. Results

3.1. Ratings of Mentors by Project Staff

Table 1 shows the mean scores across the 14 mentors who completed the training course for each of the five teaching domains (with a maximum score of 7 in each) on which they had been assessed by the project staff. At the start, most mentors were weakest in vocabulary and remained so at the end of the training. However, in all the domains, there was a statistically significant increase in their ratings (paired t-tests: p < 0.005) with a very large effect size, although the range of scores within the group on each domain also remained (from 2 to 6) as indicated by the standard deviations. The mean total score at the start was 17.3 (range 9 to 24), and at post-test, the mean score was 23.8 (range 12 to 30). As the maximum possible score was 42, this would indicate that there remained room for improvement in their teaching performance even at the end of the programme, especially in their verbal explanations.

Table 1.

The means (and standard deviations) of ratings given by project leaders on the mentors before and after training on teaching and music performance (n = 14).

The mentors were rated similarly on three domains of musical performance. Each domain had a maximum score of 30 (a maximum of 90 overall). As Table 1 shows for the three domains, there was a statistically significant increase in the mentors’ scores (paired t-tests: p < 0.001) with a very large effect size. Thus, their total scores rose from a mean of 52.5 to 72.2 (p < 0.001). However, the range of scores was wide, even at post-test (42 to 85). Nonetheless, four music mentors had scores of over 80 out of 90 on their musical performance.

3.2. Mentors’ Self-Ratings

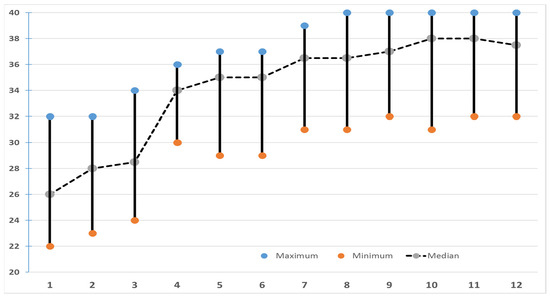

Each month during the training, the mentors rated themselves on a measure of self-esteem and musical self-efficacy. Median, maximum and minimum scores for the group were calculated for each month, and they are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The median, maximum and minimum self-esteem scores for the group of mentors over the 12 months of training (n = 14).

All of the mentors in each month had scores above the cut-off for low self-esteem (15 and under). However, across the months, the scores ranged from 22 to 40 (maximum), which reflects the variation across the mentors. There was no statistical difference in mean scores in the first three months of the programme but there was a significant rise at month four and a continuing rise up until month 9 when ceiling effects started to have an impact, and the scores were not significantly different in the last four months of training. In these months, 12 of the 14 tutors had scores of 35 or above.

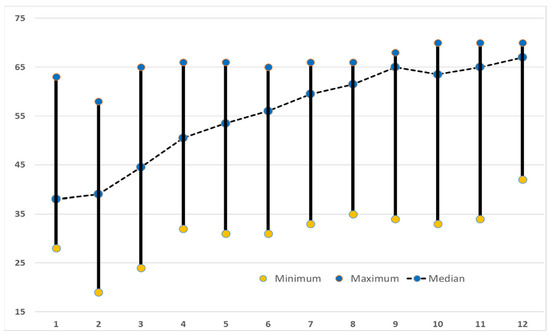

Each month, the tutors also rated themselves on a measure of musical self-efficacy. Figure 2 shows the mean scores for the 14 tutors across the months of the project.

Figure 2.

The median, maximum and minimum musical efficacy scores for the group of mentors over the 12 months of training (n = 14).

There was a significant increase in the median scores from the third to the ninth month of the training (paired t-tests, p < 0.001), and for the last four months, they remained level and close to the maximum score of 70. Indeed, nine mentors had rated scores of over 65 in the last two months. However, across all the months, the scores varied from a low of 19 to a high of 70, which reflects the individual variation among the tutors on this self-rating measure. Moreover, two mentors accounted for the lower scores across all the months and made comparatively little increase in their ratings over the 12 months. They dropped out of the project.

3.3. Inter-Relationships among the Quantitative Measures

Spearman rank-order correlations were used to examine the relationship between the two measures rated by the mentors, as well as with the ratings of their teaching and musical performance by the project staff. The scores provided at the start and the end of the training were correlated and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Spearman rank-order correlations between the four measures.

The mentors’ self-ratings on self-esteem and musical efficacy were significantly correlated but shared less than 50% of the variance, which indicates that they were measuring somewhat different concepts. At the start of the training, there was no significant relationship between the self-esteem ratings of mentors and the two ratings provided by the project staff. However, at the end of the training, these correlations were significant, which could be interpreted as confirmation by the project staff of increased self-esteem felt by mentors.

The mentors’ ratings of their musical self-efficacy were correlated with the two measures provided by the project staff, most notably at the end of the training, which suggests some validation of the mentor’s self-perceptions with those of the project staff regarding their teaching and musical competence.

Finally, the two measures used by the project staff—teaching and musical performance—were correlated significantly at the end of the training but at a level that suggests that there could be variations among mentors, with some better in teaching than in musical performance and vice versa.

3.4. Mentors’ Perceptions

The transcripts of the focus groups held with the mentors were thematically analysed using an approach recommended by Braum and Clarke [31]. Four main themes emerged from their discussions.

First, they spoke of their personal growth and development and increased confidence, self-esteem and feelings of empowerment.

Sparks empowers us and each other to do better. Disability people can do anything if they put their mind to it.

Way before I had low self-esteem, whenever I joined (Sparks) and met the others—it changed my confidence as a whole. Teaching the children gave me confidence.

I can now speak in public, before I could sing in public but not speak.

Sparks has developed our skills as teachers and musicians. It has taught to help our own wellbeing. Learning about yourself is important.

I’m proud of being a teacher and being part of this community.

When new mentors come in, it is important for us to be role models for them. They can be terrified, panicking, we show them they do not need to worry- watch me.

The second theme was related to the sense of community and belonging that they experienced by being part of the Project.

Project Sparks is like an adoptive family, we are very supportive of each other and stay connected we’re like one social bubble.

Education is important in these hard times, I’ve an amazing involvement with this community—we’ve learnt so much about ourselves.

My safe place is Sparks—I can chill and be myself. No one talks down to me

We have great craic, mess around with each other, we’re not always serious. We also have a good laugh with the children. I’m excited going to the schools.

In the third theme, the mentors spoke of how their perceptions of being disabled had been altered and how others’ perceptions should change.

I accept that I have a disability, but I would not change my life for the world. I don’t dwell on the past. It helps me teaching.

We’re open about our disabilities The kids in school see what people with disability can do. A student with no hands as a drummer.

After our project a pupil with a disability stood up and told his class about it. Doing what we had showed him.

Project Sparks is changing history; other teachers do not do inclusion. We’re changing the next generation to be more caring, more equal and to have more empathy.

Their love of music and its value in their lives formed the fourth theme.

Music is the ultimate form of expression for me. Music has been my whole life; told me how to talk.

Music is wellbeing—it makes you feel good about yourself.

My love of music grew three sizes and keeps on growing.

In sum, the mentors’ reflections show the gains they accrued from participating in the project, but also the importance of their involvement with school children and the role that music has played and continues to play in their lives.

3.5. Pupils’ Perceptions of the Mentors

The children were asked to rate a single item in a self-completion questionnaire, namely: “It would be good to have a teacher with disabilities in my school”. A five-point scale was provided, ranging from ‘Big No: No; Maybe: Yes: Big Yes’. Before the project, 43.6% chose Yes or Big Yes (with 45.3% selecting Maybe). After the project, the equivalent percentages were 62.6% Yes (31.7% Maybe).

A subset of pupils (N = 116) whose schools took part later in the Sparks Project were asked some additional questions to further explore their reactions to people with disabilities as teachers. Table 3 summarises their responses to the items asked (note that the wording was changed in the questions asked after the project to the “leaders in the project”). The last three items were scored out of 10.

Table 3.

The means and (SDs) given to the mentors with disabilities.

As Table 3 shows, there were large increases in all the ratings given to the mentors, with ceiling effects present as the scores after participating in the project came close to the maximum of 10.

The relationship that the mentors had forged with the pupils was further evidenced by the number of thank-you cards and small gifts they were given by many pupils at the end of the project. One parent in her feedback to the school, noted: “She loved the leaders and how they taught them songs and instruments and in her words were so amazing, she even got emotional about one of the leaders’ stories growing up as a child.”

3.6. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Mentors

A thematic content analysis of six teachers’ observations of the mentors when working with their pupils identified three main themes.

First, it evidenced the relationship they had forged with the children.

At the beginning, they (pupils) were quite shy and quite afraid to actually approach any of the leaders and whenever leaders would come over to chat, they were still quite shy. By the end, there was none of that at all.(T2)

They (mentors) were so tuned into the children and so enthusiastic.(T3)

(They had) a natural engagement with the children regardless of ability, or social background, or the varying sort of educational or social needs children may have, everybody was included.(T6)

The second theme was the openness and confidence of the mentors in answering the children’s questions.

They (mentors) told them, ’no matter what, if you think your question is silly, or if it’s going to be hurtful to us, just you ask it’. To give them that idea of what it was like to have maybe autism or to have a physical disability.(T5)

The facilitators (mentors) were so honest about their own situations, or their own difficulties, or their own needs, or requirements, there was an atmosphere of openness. They were able to tweak into the children’s mindset, ‘we’re all different, you’re different, you like different things, people are good at this, people are not so good at this, people get angry at this, people get not so angry’, you know, ‘we’re all different.’(T6)

A third theme was the esteem the pupils had for their mentors.

What the children got of working with (the mentors) was unbelievable. It changed their whole perception of what they thought that these people could do.(T4)

One afternoon I did a circle time with a tag line of “someone who I would like to be like”. The children were all naming the leaders, the leaders with special needs.... And they were all able to give good reasons as to why: because she is always bright and happy, because he is an amazing drummer, because she is a great dancer.(T1)

In sum, the teachers confirmed the confidence and self-esteem that the mentors brought to the project and the relationships they built with the pupils.

4. Discussion

This study was unique in a number of ways. The focus on music with both the mentors and the school pupils confirmed the power of music to enhance the well-being of both parties, although, in this instance, this was evidenced more so for the mentors. Furthermore, the project built on the musical interests and talents of the mentors rather than focusing on remediating their impairments or an overt focus on promoting their emotional wellbeing. The five attributes of flourishing noted in the introduction were emphasised in the training programme, with a central focus on building supportive relationships among the participants as they became mentors of one another as well as for the school pupils. Finally, the mentors applied their talents and skills in leading music sessions to primary school pupils, which ensured they received affirmation from pupils and teachers and not just from project personnel.

The study expands our understanding of the causal mechanisms between music and boosting the self-esteem and well-being of youth with disabilities by building on a youth empowerment model [15] and confirming the context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) model developed by another music project with disadvantaged youth to identify the elements that contributed to successful outcomes [33,34]. Thus, a supportive context was achieved by focusing on the musical talents and interests of the youth with disabilities; connecting them as a group; building trust with the trainers and with one another; and the provision by the trainers of individualised guidance on developing their teaching and musical skills.

The mechanisms mobilised by the project were developing the youths’ feelings of competence musically and as peer mentors, creating a safe and protective environment for them to be creative and to take on new challenges and building a self- and group identity as music mentors.

The resulting outcomes were increased self-esteem and self-confidence, the relationships they had built with other youth and the school pupils, a re-appraisal of their identity as a person with a disability and fulfilling a valued role in the schools. Although no formal measures of mental wellbeing were undertaken, it was evident from their reports and those from the trainers and schoolteachers that the youth were flourishing and showed little signs of the mental health problems noted in the introduction. Moreover, they will hopefully have developed the resilience needed to sustain good mental health, although, to date, there have been few robust studies on this topic with disabled youth [35] and seemingly no longitudinal studies to determine if such positive youth development interventions achieve this longer-term outcome with non-disabled youth.

The approaches used in the project are likely not confined to music-based interventions for youth with disabilities. Indeed, the CMO model could likely be applied to other arts-based interventions such as dance [36] and drama [37] or incorporated into sports and outdoor adventure programmes as has happened with non-disabled youth [15]. Indeed, the approach centres around the interests and talents of the youth with disabilities, which challenges support services to respond accordingly. Equally, as happened in this study, young people may initially enrol in a music project but find it is not suited to them. Providing an alternative intervention for them is not easily found in current service provision.

Future research will overcome some of the other limitations of the current study. The project depended on the particular talents and skills of the project staff, and the methods used need to be replicated by others to establish the potential for this music-mentoring programme to be implemented more widely. Likewise, testing the intervention with a wider range of youth with disabilities would help to refine the inclusion criteria for youth wishing to join the project and avoid drop-outs. The impact of the intervention on youth who have been diagnosed with mental health problems would help ascertain its applicability as a treatment resource.

5. Conclusions

A training programme in music mentoring was developed and evaluated with 14 youth with various disabilities. It included the real-world experience of applying the training in a school-based music project with over 200 pupils aged nine years in four schools. Evaluation data were obtained from project staff, self-ratings by the mentors and through group interviews with them, as well as from school pupils and teachers. The study confirmed the benefit of music and peer mentoring as a means of promoting the self-esteem and self-confidence of youth with disabilities. Further research is needed on the longer-term mental health benefits this intervention can offer to youth with disabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and E.C.; methodology, E.M., E.C. and R.M.; formal analysis, R.M.; investigation, R.M.; resources, E.M. and E.C.; data curation, E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M., E.M. and E.C.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M. and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project Sparks received funding from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation to undertake the work in schools and cover the costs of evaluating its impact.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as under UK regulations, it was classed as an evaluation/audit of service delivery.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study and assurances were given about the confidentiality of the information they provided.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper is available on reasonable requests to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to the schools and the head teachers for facilitating the collection of information from the pupils and parents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hudson, C.C.; Hall, L.; Harkness, K.L. Prevalence of Depressive Disorders in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 47, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.G.; Rossetti, A.; Crespi, G.; Clerici, M. Prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders in adults and adolescents with intellectual disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 33, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Shen, C.P.Y. Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Physical Illness: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 36, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, M.-C.; Kassee, C.; Besney, R.; Bonato, S.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.; Szatmari, P.; Ameis, S.H. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M.; Harkins, C.; Robinson, M.F.; Mazurek, M.O. Treatment of Depression in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 78, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.R.; Kerr, M. Antidepressant use in adults with intellectual disability. Psychiatrist 2010, 34, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, V.; Grant, J.A.; Strauss, B. Psychosocial Factors in Disease and Treatment—A Call for the Biopsychosocial Model. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hästbacka, E.; Nygård, M.; Nyqvist, F. Barriers and facilitators to societal participation of people with disabilities: A scoping review of studies concerning European countries. Alter 2016, 10, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, R. A National Survey of the Social and Emotional Differences Reported by Adults with Disability in Ireland Compared to the General Population. Disabilities 2021, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.C.; White, S.W. Socio-emotional determinants of depressive symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism 2020, 24, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, T.; Rodgers, M.; Marshall, D.; Melton, H.; Rees, R.; Wright, K.; Sowden, A. Support for adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual impairment: Systematic review. Autism 2017, 22, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, L.; Moore, D.; Nunns, M.; Coon, J.T.; Ford, T.; Berry, V.; Walker, E.; Heyman, I.; Dickens, C.; Bennett, S.; et al. Experiences of interventions aiming to improve the mental health and well-being of children and young people with a long-term physical condition: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 832–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, G.; Skinner, M.; Plaut, D.; Moss, C.; Kapungu, C.; Reavley, N. A Systematic Review of Positive Youth Development Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, Washington, DC, YouthPower Learning, Making Cents International. 2017. Available online: https://www.youthpower.org/systematic-review-pyd-lmics (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Waid, J.; Uhrich, M. A Scoping Review of the Theory and Practice of Positive Youth Development. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 50, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/what-is-the-evidence-on-the-role-of-the-arts-in-improving-health-and-well-being-a-scoping-review-2019 (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Caleon, I.S. The Role of Music-Based Activities in Fostering Well-Being of Adolescents: Insights from a Decade of Research (2008–2018). In Artistic Thinking in the Schools; Costes-Onishi, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levstek, M.; Banerjee, R. A Model of Psychological Mechanisms of Inclusive Music-Making: Empowerment of Marginalized Young People. Music Sci. 2021, 4, 20592043211059752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, L.; Campbell-Jack, D.; Bertolotto, E. Evaluation of the Peer Support for Mental Health and Wellbeing Pilots. Department for Education, London. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/34998/1/Evaluation_of_the_peer_support_pilots_-_Main_report.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Douglas, L.; Jackson, D.; Woods, C.; Usher, K. Reported outcomes for young people who mentor their peers: A literature review. Ment. Health Pract. 2018, 21, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haft, S.; Chen, T.; Leblanc, C.; Tencza, F.; Hoeft, F. Impact of mentoring on socio-emotional and mental health outcomes of youth with learning disabilities and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizing, R.L. Mentoring Together: A Literature Review of Group Mentoring. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2012, 20, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarobe, L.; Bungay, H. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chi, M.T.H.; Wylie, R. The ICAP Framework: Linking Cognitive Engagement to Active Learning Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 49, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, E.; Curran, E.; McConkey, R. Changing Children’s Attitudes to Disability through Music: A Learning Intervention by Young Disabled Mentors. Disabilities 2022, 2, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, E.; Curran, E.; McQueen, P.; McConkey, R. ‘I Never Thought I could Teach, now I help kids to grow up Believing they can be Creative’: The Effectiveness of Disabled Musicians as Music Mentors in Primary Schools. 2022; Paper submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. An Introduction to Scientific Realist Evaluation; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment. Levels of Progression in Communication across the Curriculum: Key Stage 3. CCEA: Belfast, UK, 2012. Available online: https://ccea.org.uk/downloads/docs/ccea-asset/Curriculum/The%20levels%20of%20progression%20for%20Communication%20Key%20Stage%203.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Music Certificate Exams. Available online: https://www.trinitycollege.com/qualifications/music/music-certificate-exams (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, L.; Williamon, A. Measuring distinct types of musical self-efficacy. Psychol. Music 2010, 39, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caló, F.; Steiner, A.; Millar, S.; Teasdale, S. The impact of a community-based music intervention on the health and well-being of young people: A realist evaluation. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 28, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Croom, A.M. Music practice and participation for psychological well-being: A review of how music influences positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Music. Sci. 2014, 19, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, A.; Heaver, B.; Brunnberg, E.; Sandberg, A.; MacPherson, H.; Coombe, S.; Kourkoutas, E. Resilience-Building with Disabled Children and Young People: A Review and Critique of the Academic Evidence Base. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2014, 5, 394–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus, B.M.; Oliveira, R.C.; de Carvalho, F.O.; Mari, J.D.J.; Arida, R.M.; Teixeira-Machado, L. Dance promotes positive benefits for negative symptoms in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mino-Roy, J.; St-Jean, J.; Lemus-Folgar, O.; Caron, K.; Constant-Nolett, O.; Després, J.; Gauthier-Boudreault, C. Effects of music, dance and drama therapies for people with an intellectual disability: A scoping review. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).