Societal Welfare Implications of Solar and Renewable Energy Deployment: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

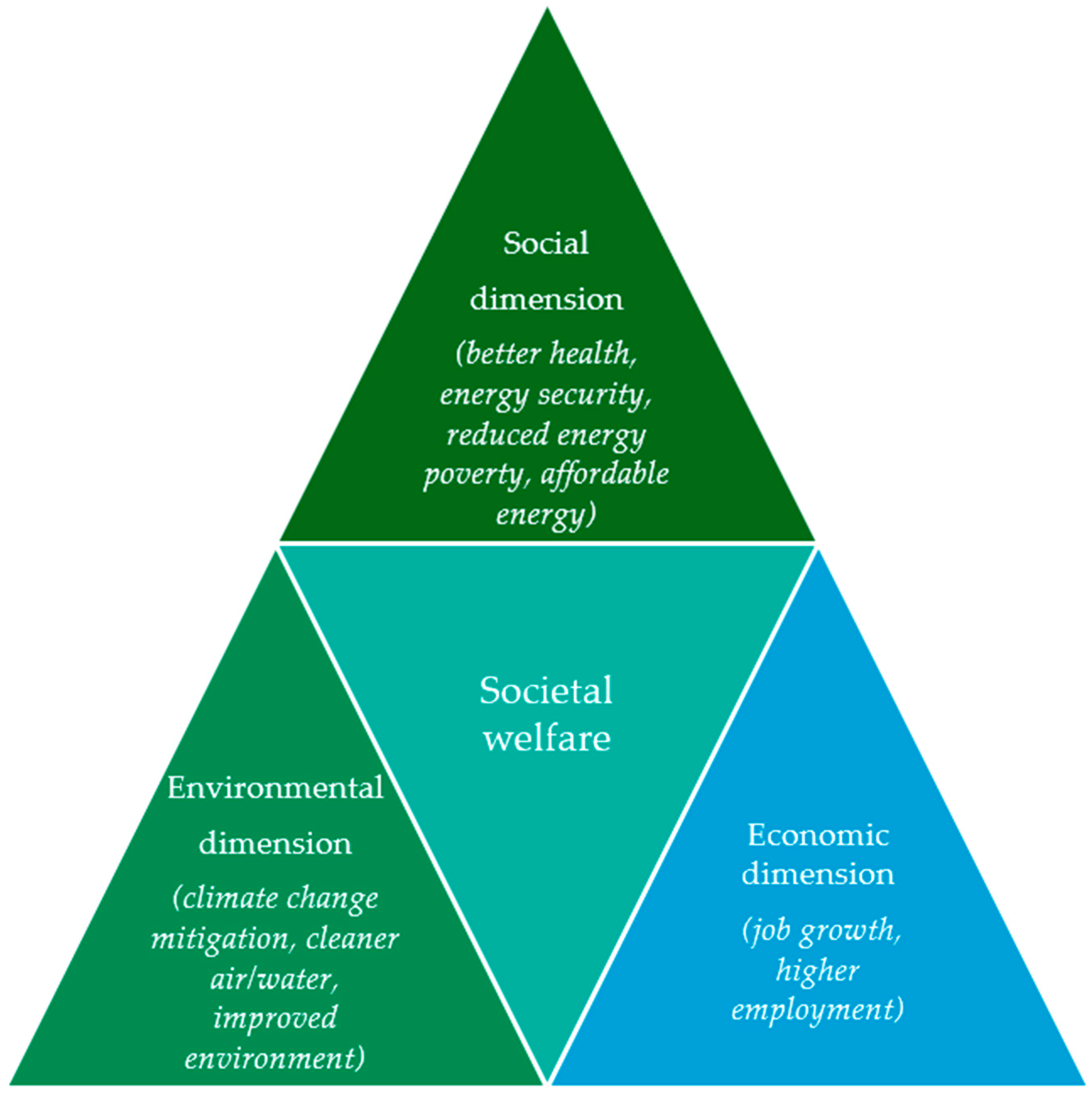

2.1. Conceptualizing Societal Welfare

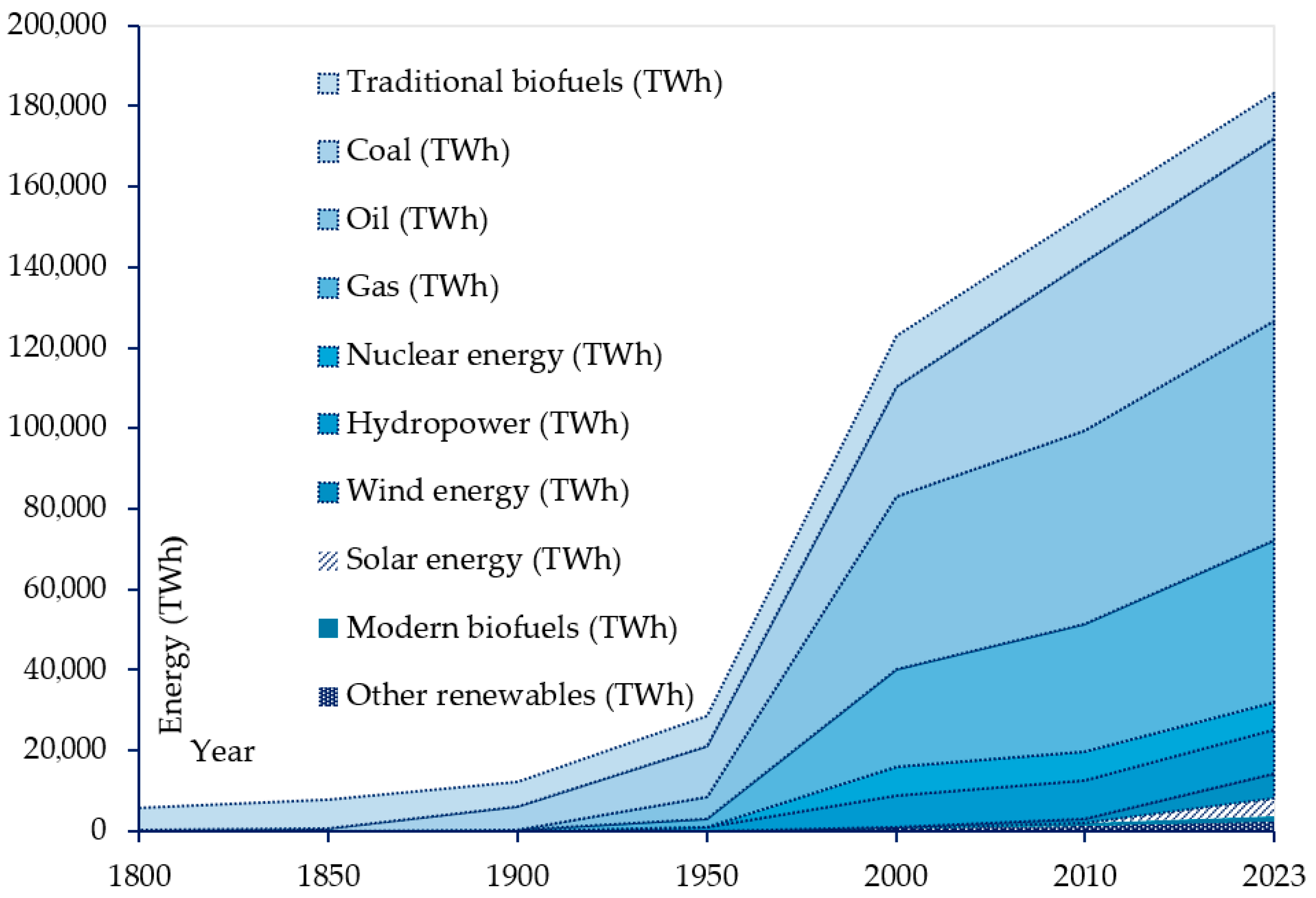

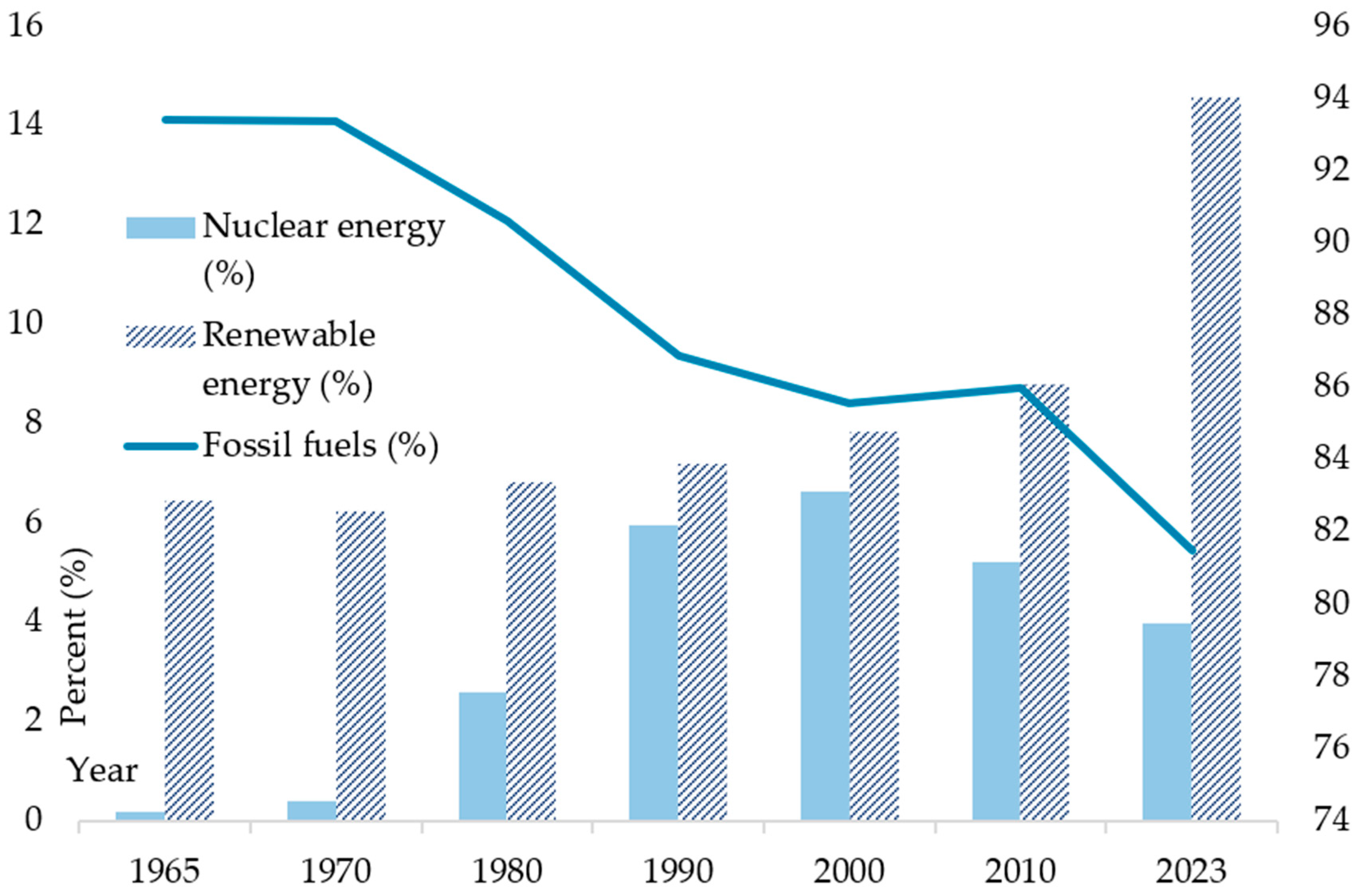

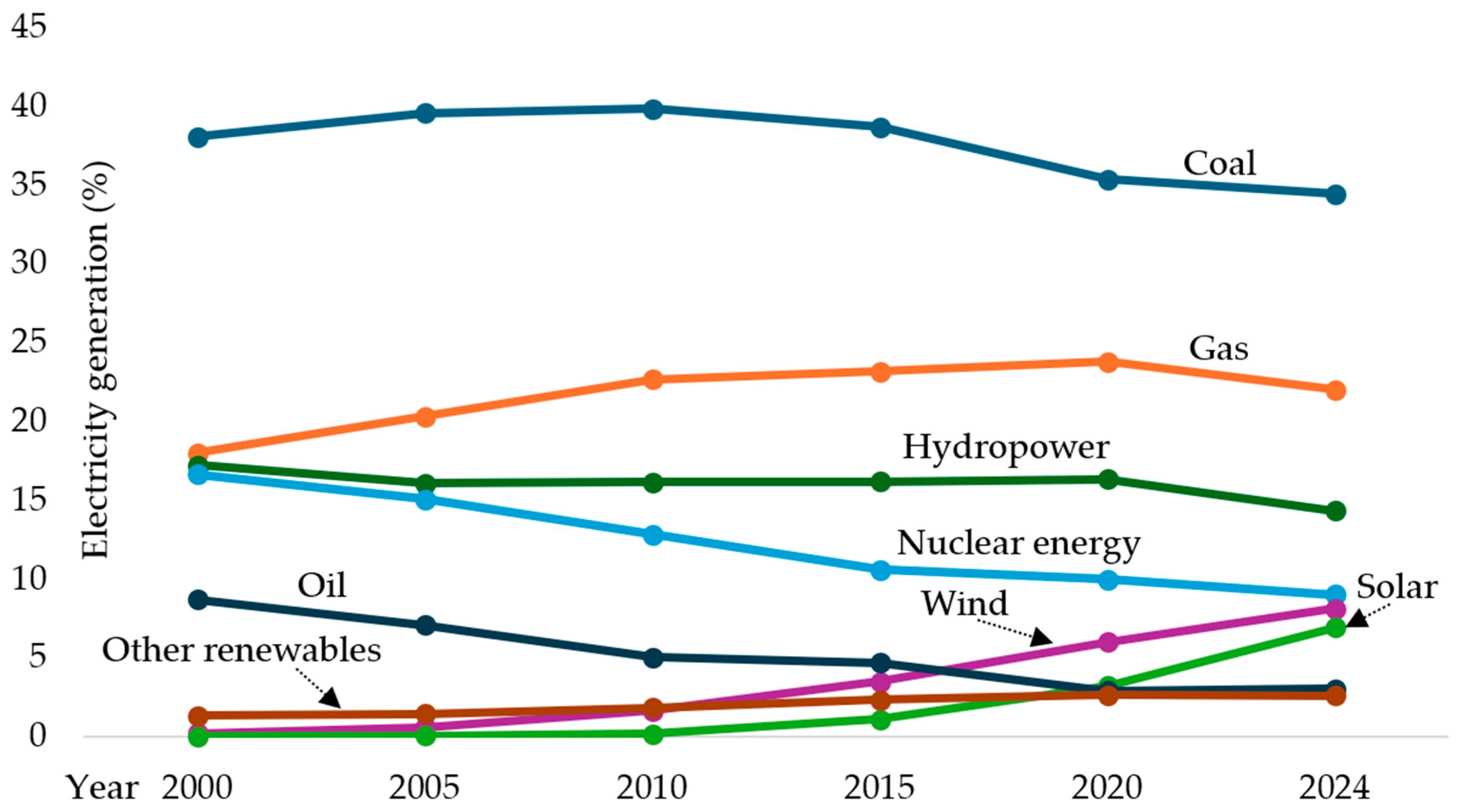

2.2. Renewable Energy

3. Materials and Methods

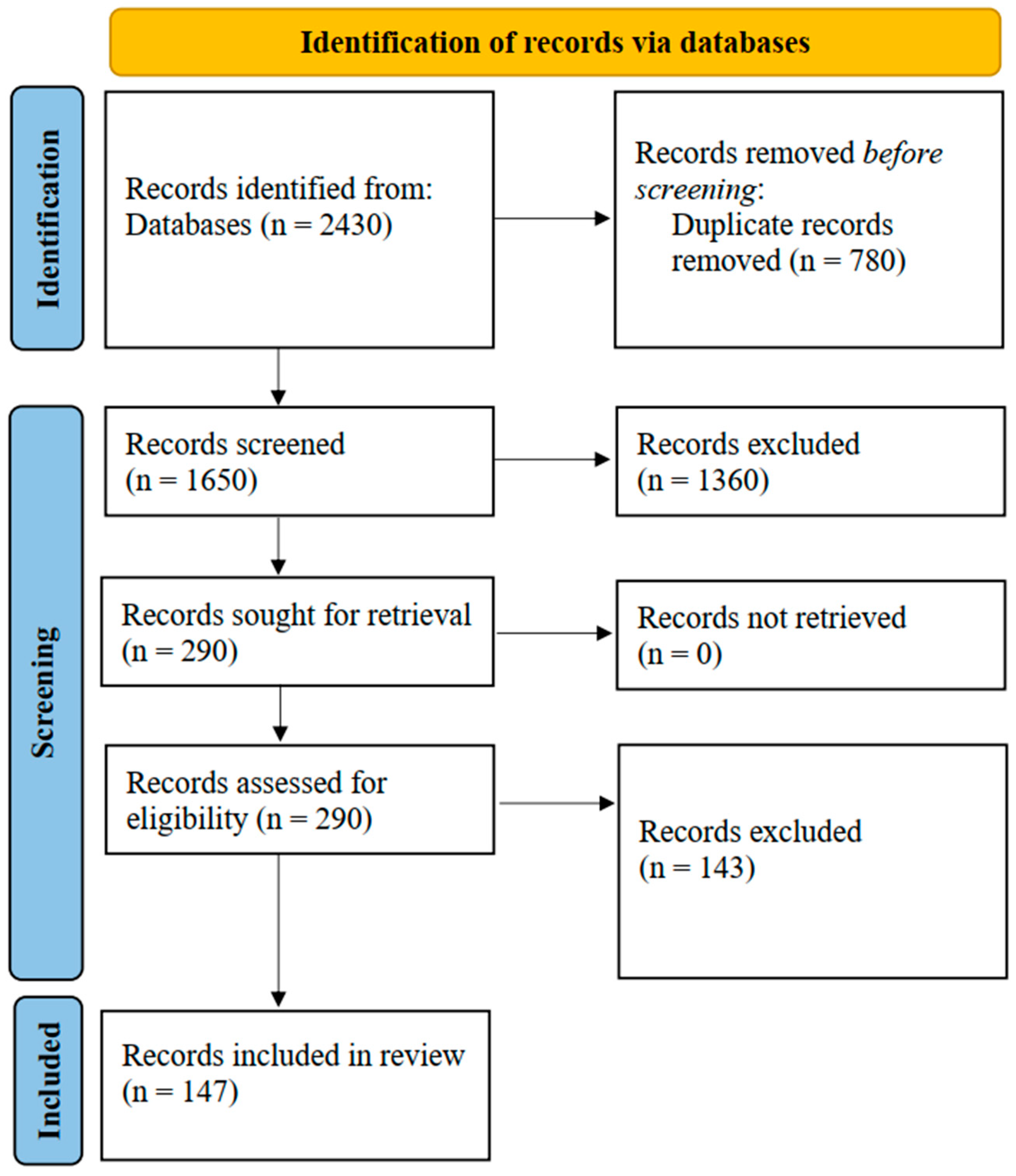

3.1. SALSA Methodology

3.2. Integration with PRISMA

3.3. Bibliometric Methods (Bibliometrix/Biblioshiny)

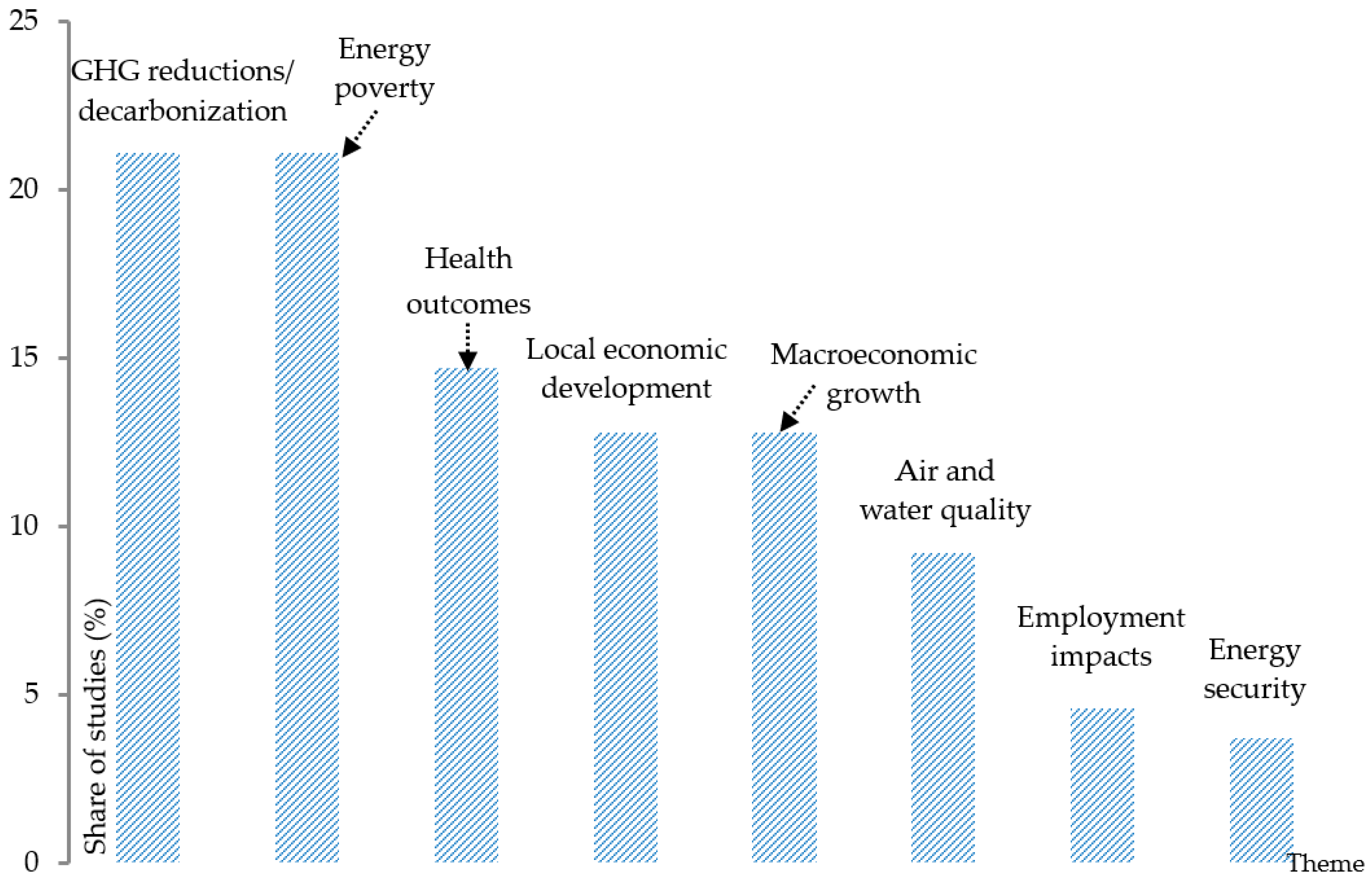

4. Results and Discussion

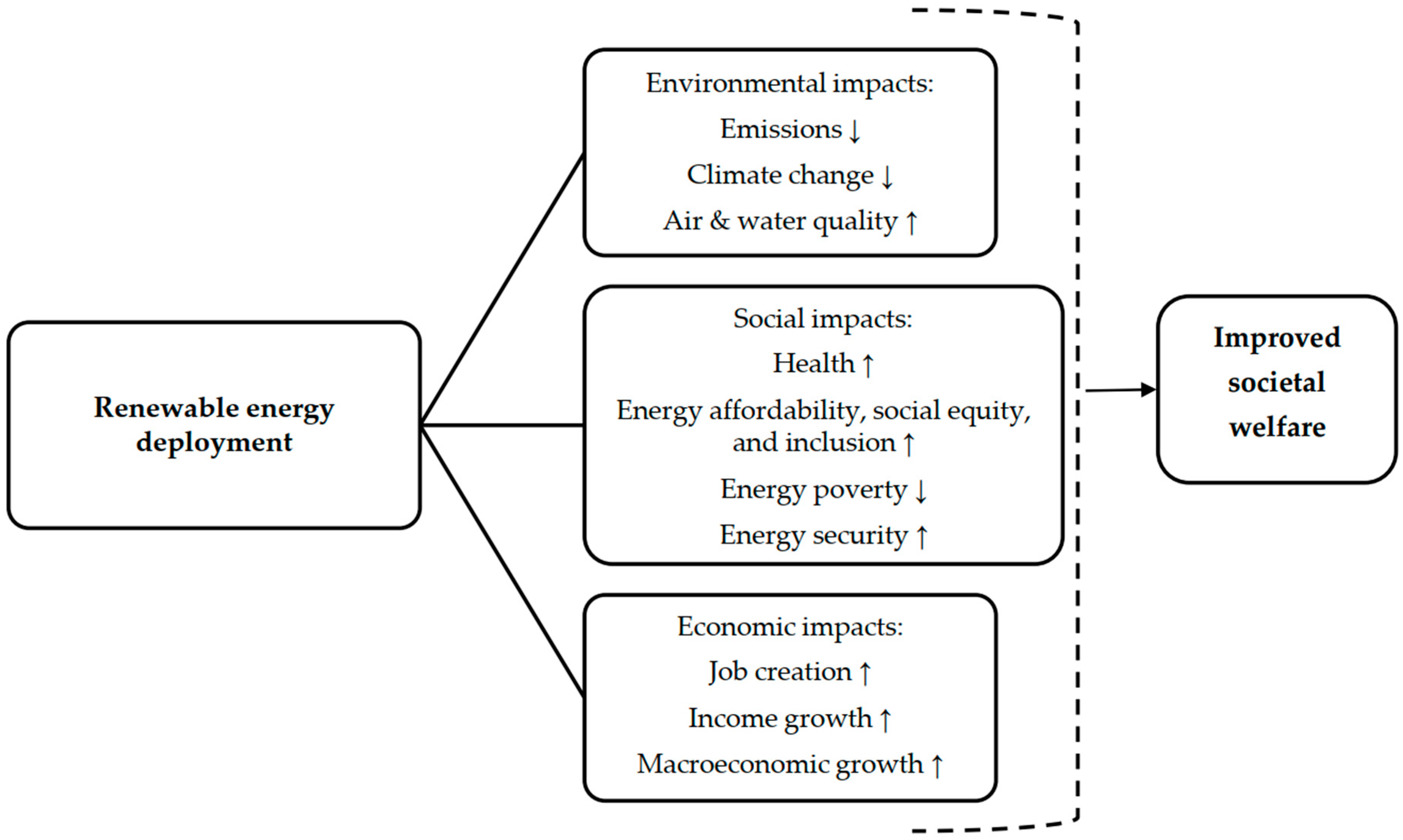

4.1. Linking Renewable Energy Technology Deployment to Societal Welfare: Environmental Benefits

4.1.1. Reduction in Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions

4.1.2. Improved Air and Water Quality

4.1.3. Barriers and Challenges

4.2. Linking Renewable Energy Technology Deployment to Societal Welfare: Social Benefits

4.2.1. Health Outcomes

4.2.2. Clean and Affordable Energy

4.2.3. Energy Poverty

4.2.4. Energy Security

4.2.5. Barriers and Challenges

4.3. Linking Renewable Energy Technology Deployment to Societal Welfare: Economic Benefits

4.3.1. Macroeconomic Growth

4.3.2. Employment Impacts

4.3.3. Local Economic Development

4.3.4. Barriers and Challenges

4.4. Mapping Renewables to Societal Welfare

| Societal Welfare Dimension | Key Renewable Energy Technologies Impact Areas | Representative Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental welfare | GHG emission reduction | Strong evidence that RETs cut CO2 emissions across regions and are pivotal for meeting climate targets. | [47,49,55] |

| Air and water quality | Decreased air pollution (e.g., SO2, NOX) and improved water-use efficiency with reduced contamination risks. | [76,77,84] | |

| Climate mitigation | RETs enable deep decarbonization in power, transport, and industry, with comparatively low life-cycle emissions, thereby mitigating climate change. | [48,66,67,68] | |

| Social welfare | Health outcomes | Reduced PM2.5 and co-pollutants decrease respiratory and cardiovascular illness; prevent premature deaths. | [77,78,80,183] |

| Energy affordability, social equity and inclusion | Long-term system and technology cost reductions; early transition phases may see temporary price increases, but mature RET mixes lower average costs. By improving access and affordability, RETs advance energy justice and reduce inequality; outcomes remain contingent on governance quality | [70,111,113,114,115,118,182,185] | |

| Energy poverty reduction | Renewable energy technologies improve access in underserved regions—especially via distributed solar and small hydro in rural contexts. | [120,127,134,135,184] | |

| Increased energy security | Renewable energy diversifies supply and reduces import dependence while improving availability, accessibility, and affordability; moreover, grid modernization and energy storage enhance system resilience. | [117,119,129,138,139,140,141,142,143,144] | |

| Economic welfare | Job creation and income growth | RET deployment yields net job creation across construction, O&M, and supply chains; solar and wind show strong employment multipliers. | [155,157,162,165] |

| Macroeconomic growth | Positive associations between renewable energy consumption and GDP/household income across multiple contexts. | [52,150,153] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wehbi, H. Powering the future: An integrated framework for clean renewable energy transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.D. A just energy transition requires research at the intersection of policy and technology. PLoS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z. Literature review and analysis of the social impact of a just energy transition. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1119877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Sovacool, B.K.; Bonaiuto, M.; Diekmann, A.; Filippini, M.; Hindriks, F.; Bergstad, C.J.; Matthies, E.; Woerdman, E. A research agenda to better understand the human dimensions of energy transitions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 672776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutulienė, S. Gyvenimo kokybė: Sąvokos apibrėžimas ir santykis su gero gyvenimo terminais. Kultūra Ir Visuomenė Soc. Tyrim. žurnalas 2012, 3, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, B. What is welfare? Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2008, 2, 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev, O.N.; Landhuis, C.E. Exploring constructs of well-being, happiness and quality of life. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Thapa, K. A Systematic Literature Review on Psychological Well-Being. Int. J. For Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. The human world. In Foundations of Sociology: Towards a Better Understanding of the Human World; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, M.W. Societies, identity, and belonging. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 2020, 164, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisieliauskas, J. Vyriausybės Išlaidų Poveikio Visuomenės Gerovei Vertinimas ES Šalyse (Assessment of Government Expenditure Effect on Welfare of Society in the EU Countries). Doctoral Dissertation, Vytautas Magnus University (Vytauto Didžiojo Universitetas), Kaunas, Lithuania, 2017; 236p. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12259/34947 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Stoll, L.; Michaelson, J.; Seaford, C. Well-Being Evidence for Policy: A Review; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mizaras, S.; Lukmine, D. Forest and society’s welfare: Impact assessment in Lithuania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited; Ofce: Paris, France, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Painuly, J.P. Barriers to renewable energy penetration; a framework for analysis. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, B.; Beuse, M.; Tautorat, P.; Schmidt, T.S. Experience curves for operations and maintenance costs of renewable energy technologies. Joule 2020, 4, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellabban, O.; Abu-Rub, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Du, E. Exploiting the operational flexibility of a concentrated solar power plant with hydrogen production. Sol. Energy 2022, 247, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.C.; Izidoro, D.L.; Násner, A.M.L.; Venturini, O.J.; Lora, E.E.S. Techno-economical evaluation of renewable hydrogen production through concentrated solar energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolaro, M.; Kittner, N. Optimizing hybrid offshore wind farms for cost-competitive hydrogen production in Germany. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 6478–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Castillo, C.A.; Yeter, B.; Li, S.; Brennan, F.; Collu, M. A critical review of challenges and opportunities for the design and operation of offshore structures supporting renewable hydrogen production, storage, and transport. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P. Energy Mix; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Opeyemi, B.M. Path to sustainable energy consumption: The possibility of substituting renewable energy for non-renewable energy. Energy 2021, 228, 120519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Gkampoura, E.C. Reviewing usage, potentials, and limitations of renewable energy sources. Energies 2020, 13, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurasz, J.; Canales, F.A.; Kies, A.; Guezgouz, M.; Beluco, A. A review on the complementarity of renewable energy sources: Concept, metrics, application and future research directions. Sol. Energy 2020, 195, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Hao, Z.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Hao, F. Spatial compounding of droughts and hot extremes across southwest and east China resulting from energy linkages. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdóttir, I.; Davidsdottir, B.; Worrell, E.; Sigurgeirsdóttir, S. Review of indicators for sustainable energy development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tudela, P.A.; Marín-Marín, J.A. Use of Arduino in Primary Education: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.; Alston, S.; Brown, M.; Bost, A. Literature review on regulatory frameworks for addressing discrimination in clinical supervision. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2023, 33, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I.; Streimikiene, D.; Balezentis, T.; Skulskis, V. A systematic literature review of multi-criteria decision-making methods for sustainable selection of insulation materials in buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H. A Technical Note on Bibliometric Analysis by Biblioshiny and VOSviewer. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. How to combine and clean bibliometric data and use bibliometric tools synergistically: Guidelines using metaverse research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Zakari, A.; Ahmad, M.; Irfan, M.; Hou, F. Linking energy transitions, energy consumption, and environmental sustainability in OECD countries. Gondwana Res. 2022, 103, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alismail, F.; Alam, M.; Shafiullah, M.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, S. Impacts of Renewable Energy Generation on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, E.; Mahama, M. Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Reduction in the Electricity Sector: Implications of Increasing Renewable Energy Penetration in Ghana’s Electricity Generation Mix. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghutla, C.; Chittedi, K.R. The effect of technological innovation and clean energy consumption on carbon neutrality in top clean energy-consuming countries: A panel estimation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 47, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Research on the dynamic relationship between China’s renewable energy consumption and carbon emissions based on ARDL model. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Izquierdo, M.; Río, P. An analysis of the socioeconomic and environmental benefits of wind energy deployment in Europe. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Acheampong, A.O. Reducing carbon emissions: The role of renewable energy and democracy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakers, A.; Stocks, M.; Lu, B.; Cheng, C.; Stocks, R. Pathway to 100% Renewable Electricity. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 9, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghahosseini, A.; Bogdanov, D.; Barbosa, L.; Breyer, C. Analysing the feasibility of powering the Americas with renewable energy and inter-regional grid interconnections by 2030. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutan, A.M.; Paramati, S.R.; Ummalla, M.; Zakari, A. Financing renewable energy projects in major emerging market economies: Evidence in the perspective of sustainable economic development. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, A.; Akbari, M. Potential of solar energy in developing countries for reducing energy-related emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Mo, D.; Gupta, R. The effects of stock market growth and renewable energy use on CO2 emissions: Evidence from G20 countries. Energy Econ. 2017, 66, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Sinha, A.; Dogan, E. The significance of renewable energy use for economic output and environmental protection: Evidence from the Next 11 developing economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 13546–13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.; Honnery, D. Can renewable energy power the future? Energy Policy 2016, 93, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Ozturk, I. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Kenya: A multivariate analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Churchill, S.; Paramati, S. The dynamic impact of renewable energy and institutions on economic output and CO2 emissions across regions. Renew. Energy 2017, 111, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Koçak, E.; Bulut, Ü. The dynamic impact of renewable energy consumption on CO2 emissions: A revisited Environmental Kuznets Curve approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, H.; Rafiq, S.; Salim, R. Economic growth with coal, oil and renewable energy consumption in China: Prospects for fuel substitution. Econ. Model. 2015, 44, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Bloch, H.; Salim, R. Determinants of renewable energy adoption in China and India: A comparative analysis. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 2700–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, S.; Salim, R.A. Non-renewable and renewable energy consumption and CO2 emissions in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmeechokchai, B.; Pradhan, B.; Chunark, P.; Chaichaloempreecha, A.; Rajbhandari, S.; Pita, P. Energy system transformation for attainability of net zero emissions in Thailand. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2022, 35, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, D.; Fowlie, M.; McCormick, G. Location, Location, Location: The Variable Value of Renewable Energy and Demand-Side Efficiency Resources. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 5, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, A.; Johnston, J.; Nelson, J.; Kammen, D. Power system balancing for deep decarbonization of the electricity sector. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Dauda, A.; Chua, H.; Tan, R.; Aviso, K. Recent advances in the integration of renewable energy sources and storage facilities with hybrid power systems. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 12, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; McMillan, C.; De La Rue Du Can, S. Electrification of Industry: Potential, Challenges and Outlook. Curr. Sustain./Renew. Energy Rep. 2019, 6, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Månsson, D. Greenhouse gas emissions from hybrid energy storage systems in future 100% renewable power systems—A Swedish case based on consequential life cycle assessment. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Nie, L.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yan, J.; Kourkoumpas, D.; Karellas, S. Comparative life cycle greenhouse gas emissions assessment of battery energy storage technologies for grid applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Miranda, M.; Bielicki, J.; Ellis, B.; Johnson, J. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of CO2-Enabled Sedimentary Basin Geothermal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Park, K. Financial Development and Deployment of Renewable Energy Technologies. Energy Econ. 2016, 59, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virah-Sawmy, D.; Sturmberg, B. Socio-economic and environmental impacts of renewable energy deployments: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcet, C. Empirical determinants of renewable energy deployment: A systematic literature review. Energy Econ. 2020, 85, 104563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, A.; Martek, I. Renewable energy policy and deployment of renewable energy technologies: The role of resource curse. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 91377–91395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayen, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Roy, S. A review on environmental impacts of renewable energy for sustainable development. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 21, 5285–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Patwa, N.; Gupta, Y. Breaking barriers in deployment of renewable energy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, H.I.; Efroymson, R.A.; McManamay, R.A. Renewable energy and biological conservation in a changing world. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 263, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, W.; Wang, C. Air Quality Benefits of Renewable Energy: Evidence from China’s Renewable Energy Heating Policy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, M.; Pu, J.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S. Large-scale renewable energy brings regionally disproportional air quality and health co-benefits in China. iScience 2023, 26, 107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.; Holloway, T. Integrating Air Quality and Public Health Benefits in U.S. Decarbonization Strategies. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 563358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, R.; Mai, T.; Millstein, D.; Barbose, G.; Bird, L.; Heeter, J.; Keyser, D.; Krishnan, V.; Macknick, J. Assessing the costs and benefits of US renewable portfolio standards. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 094023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, J.; Hughes, E.; Michanowicz, D.; Heo, J.; Allen, J.; Williams, A. Climate and health benefits of increasing renewable energy deployment in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akça, E. Do renewable energy sources improve air quality? Demand- and supply-side comparative evidence from industrialized and emerging industrial economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 31, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Suh, D.; Joo, S. A Dynamic Analysis of Air Pollution: Implications of Economic Growth and Renewable Energy Consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Yu, Z.; Belhadi, A.; Mardani, A. Investigating the effects of renewable energy on international trade and environmental quality. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 272, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A. Water-energy nexus: Desalination technologies and renewable energy sources. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21009–21022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guan, W.; Cao, Y.; Bao, Q. Role of green finance policy in renewable energy deployment for carbon neutrality: Evidence from China. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, A.; Pata, U. The role of ICT, R&D spending and renewable energy consumption on environmental quality: Testing the LCC hypothesis for G7 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, I.; Kammoun, A.; Kefi, M. To what extent does renewable energy deployment reduce pollution indicators? the moderating role of research and development expenditure: Evidence from the top three ranked countries. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1096885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Donkor, M.; Jin, C.; Musah, M.; Nkyi, J.A. Do financial development, urbanization, economic growth and renewable energy promote the emission mitigation agenda of Africa? Evidence from models that account for cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1269416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghani, M.; Archer, C.L. Impacts of replacing coal with renewable energy sources and electrifying the transportation sector on future ozone concentrations in the US under a warming climate. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Laranjeira, E.; Soares, I. Health Benefits from Renewable Electricity Sources: A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenda, A.M.; Behrsin, I.; Disano, F. Renewable energy for whom? A global systematic review of the environmental justice implications of renewable energy technologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101837–1018349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdiwansyah, F.; Mahidin, F.; Husin, H.; Nasaruddin, F.; Zaki, M.; Muhibbuddin, F. A critical review of the integration of renewable energy sources with various technologies. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, K.; Chowdhury, C.; Yadav, D.; Verma, R.; Dutta, S.; Jaiswal, K.S.; Selvakumar, K. Renewable and sustainable clean energy development and impact on social, economic, and environmental health. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutet, L.; Bernard, P.; Green, R.; Milner, J.; Haines, A.; Slama, R.; Temime, L.; Jean, K. The public health co-benefits of strategies consistent with net-zero emissions: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e145–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasoulinezhad, E.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. How is mortality affected by fossil fuel consumption, CO2 emissions and economic factors in CIS region? Energies 2020, 13, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, E.A.; Silvern, R.F.; Vodonos, A.; Dupin, E.; Bockarie, A.S.; Mickley, L.J.; Schwartz, J. Air quality and health impact of future fossil fuel use for electricity generation and transport in Africa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13524–13534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelieveld, J.; Klingmüller, K.; Pozzer, A.; Pöschl, U.; Fnais, M.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Cardiovascular disease burden from ambient air pollution in Europe reassessed using novel hazard ratio functions. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Eguino, M. Energy poverty: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machol, B.; Rizk, S. Economic value of US fossil fuel electricity health impacts. Environ. Int. 2013, 52, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byaro, M.; Rwezaula, A. The health impacts of renewable energy consumption in sub-Saharan Africa: A machine learning perspective. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 57, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, M.; Hanif, I.; Alamoudi, H. Impact of environmental pollution on human health and financial status of households in MENA countries: Future of using renewable energy to eliminate the environmental pollution. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Razzaq, A.; Chupradit, S.; An, N.; Abdul-Samad, Z. The role of renewable energy consumption and health expenditures in improving load capacity factor in ASEAN countries: Exploring new paradigm using advance panel models. Renew. Energy 2022, 191, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kaul, M.; Chandra, S.; Rawandale, C. The impact of renewable energy, carbon emissions, and fossil fuels on health outcomes: A study of West African countries. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2025, 35, 2683–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Colantonio, E.; Gattone, S. Relationships between Renewable Energy Consumption, Social Factors, and Health: A Panel Vector Auto Regression Analysis of a Cluster of 12 EU Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L.C.; Islam, M.A.; Ray, S.; Mohamed Yusop, N.Y.; Ridzuan, A.R. CO2 emissions from renewable and non-renewable electricity generation sources in the G7 countries: Static and dynamic panel assessment. Energies 2023, 16, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Khan, M.B.; Shabbir, M.S.; Khan, G.Y.; Usman, M. Nexus between non-renewable energy production, CO2 emissions, and healthcare spending in OECD economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 47286–47297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, R.L.; Julius, O.O.; Nwokolo, I.C.; Ajide, K.B. The role of technology in the non-renewable energy consumption-quality of life nexus: Insights from sub-Saharan African countries. Econ. Change Restruct. 2022, 55, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbose, G.; Wiser, R.; Heeter, J.; Mai, T.; Bird, L.; Bolinger, M.; Carpenter, A.; Heath, G.; Keyser, D.; Millstein, D. A retrospective analysis of benefits and impacts of US renewable portfolio standards. Energy Policy 2016, 96, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, D.; Wiser, R.; Bolinger, M.; Barbose, G. The climate and air-quality benefits of wind and solar power in the United States. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pata, U. Do renewable energy and health expenditures improve load capacity factor in the USA and Japan? A new approach to environmental issues. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2021, 22, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Pan, Y.; Ke, X.; Agha, M.; Borah, P.; Akhtar, M. European transition toward climate neutrality: Is renewable energy fueling energy poverty across Europe? Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Gkampoura, E. Assessing Fossil Fuels and Renewables’ Impact on Energy Poverty Conditions in Europe. Energies 2023, 16, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A.; Scandurra, G. Boosting green energy transition to tackle energy poverty in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 110, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridou, G.; Matsumoto, K.; Doumpos, M. Evaluating the energy poverty in the EU countries. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.; Hosan, S.; Karmaker, S.; Chapman, A.; Saha, B. Clarifying the linkage between renewable energy deployment and energy justice: Toward equitable sustainability. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Obaideen, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; AlMallahi, M.N.; Shehata, N.; Alami, A.H.; Mdallal, A.; Hassan, A.A.M.; Sayed, E.T. Wind energy contribution to the sustainable development goals: Case study on London array. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Iqbal, N.; Saydaliev, H. The role of technological progress and renewable energy deployment in Green Economic Growth. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Uluğ, E.; Oralhan, B. The impact of electricity from renewable and non-renewable sources on energy poverty and greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs): Empirical evidence and policy implications. Energy 2023, 272, 127125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Radulescu, M. Examining the role of nuclear and renewable energy in reducing carbon footprint: Does the role of technological innovation really create some difference? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhou, J.; Ren, J. Alleviating Energy Poverty through Renewable Energy Technology: An Investigation Using a Best-Worst Method-Based Quality Function Deployment Approach with Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, K.; Tian, S.; Sun, R.; Cui, K.; Zhang, Y. Nexus between energy poverty and sustainable energy technologies: A roadmap towards environmental sustainability. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 888080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Meneguzzo, F. Distributed Generation from Renewable Energy Sources: Ending Energy Poverty across the World. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 2000126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawusu, S. Evolving energy landscapes: A computational analysis of the determinants of energy poverty. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yuan, Z.; Lee, C.; Chang, Y. The impact of renewable energy technology innovation on energy poverty: Does climate risk matter? Energy Econ. 2022, 116, 106427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.; Lira, M.; Gonçalves, M.; De Oliveira Lopes Da Silva, O.; Jean, W.; Júnior, R. The Role of Renewable Energies in Combating Poverty in Brazil: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, L.; Rancilio, G.; Radaelli, L.; Merlo, M. Renewable energy communities and mitigation of energy poverty: Instruments for policymakers and community managers. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 39, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, K.; Zhao, Z.; Atif, F.; Dilanchiev, A. Nexus Between Energy Poverty and Technological Innovations: A Pathway for Addressing Energy Sustainability. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 888080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, R.; Qu, Y.; Hao, Y. The Road to Eliminating Energy Poverty: Does Renewable Energy Technology Innovation Work? Energy J. 2024, 45, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, A. Mitigating Energy Poverty: Mobilizing Climate Finance to Manage the Energy Trilemma in Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R.; Feenstra, M. Do renewable energy communities deliver energy justice? Exploring insights from 71 European cases. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, F.; Marrasso, E.; Samanta, S.; Sasso, M. Addressing Energy Poverty in the Energy Community: Assessment of Energy, Environmental, Economic, and Social Benefits for an Italian Residential Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, L.; Benalcazar, P. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Sustainable Rural Development: Perspectives and Challenges in Energy Systems Modeling. Energies 2023, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, K.; Zhao, Z.; Irfan, M. Factors influencing consumers’ willingness to adopt renewable energy technologies: A paradigm to alleviate energy poverty. Energy 2024, 309, 133005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, W.; Bai, C. Can renewable energy technology innovation alleviate energy poverty? Perspective from the marketization level. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Dong, K.; Dong, X.; Shahbaz, M. How renewable energy alleviate energy poverty? A global analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longe, O.M. An assessment of the energy poverty and gender nexus towards clean energy adoption in rural South Africa. Energies 2021, 14, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Zhan, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Chu, X.; Teng, Y. Estimation of household energy poverty and feasibility of clean energy transition: Evidence from rural areas in the Eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Analyzing the Role of Renewables in Energy Security by Deploying Renewable Energy Security Index. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2023, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B.; Nguyen, N.; Shahbaz, M. Energy security as new determinant of renewable energy: The role of economic complexity in top energy users. Energy 2022, 263, 125799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, A.; Dobbins, A.; Fahl, U.; Singh, A. Drivers of renewable energy deployment in the EU: An analysis of past trends and projections. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 26, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cergibozan, R. Renewable energy sources as a solution for energy security risk: Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overland, I.; Juraev, J.; Vakulchuk, R. Are renewable energy sources more evenly distributed than fossil fuels? Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.C.R.; Majid, M.A. Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: Current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakhil, A.M.; Nassani, A.A.; Awan, U.; Abro, M.M.Q.; Zaman, K. Determinants of green logistics in BRICS countries: An integrated supply chain model for green business. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, M.; Radulescu, M.; Cifuentes--Faura, J.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. The role of renewable energy policies in TACKLING energy poverty in the European UNION. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.; Schneider, N.; Wüstenhagen, R. Dynamics of social acceptance of renewable energy: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2023, 181, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Aslanidis, P. Addressing Multidimensional Energy Poverty Implications on Achieving Sustainable Development. Energies 2023, 16, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakowska, J.; Ozimek, I. Renewable Energy Attitudes and Behaviour of Local Governments in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Economic welfare impacts from renewable energy consumption: The China experience. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 5120–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Kaminitz, S. The significance of GDP: A new take on a century-old question. J. Econ. Methodol. 2023, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J.; Sebestyén, T.T.; Bartók, B. Evaluation of renewable energy sources in peripheral areas and renewable energy-based rural development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimeris, P.; Bithas, K.; Richardson, C.; Nijkamp, P. Hidden linkages between resources and economy: A “Beyond-GDP” approach using alternative welfare indicators. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y.; Mishchuk, H.; Samoliuk, N.; Yurchyk, H. Impact of income distribution on social and economic well-being of the state. Sustainability 2020, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, A. Measuring welfare beyond GDP. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2019, 249, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García--Riazuelo, Á.; Duarte, R.; Sarasa, C. The Long--term Socioeconomic Impacts of Renewable Energy Deployment: Lessons From Case Studies in European Rural Regions. J. Reg. Sci. 2025, 65, 1094–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampene, A.; Li, C.; Nsiah, T. Catalyzing renewable energy deployment in the Mercosur economies: A synthesis of human capital, technological innovation and green finance. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.; Yap, P.S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, environmental, and economic consequences of integrating renewable energies in the electricity sector: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, S.; Tirth, V.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshehery, S.; Kshirsagar, P. Contribution of renewable energy sources to the environmental impacts and economic benefits for sustainable development. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Das, B.; Hasan, M. Integrated off-grid hybrid renewable energy system optimization based on economic, environmental, and social factors for sustainable development. Energy 2022, 250, 123823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, N.; Gutiérrez, E.; Lacuesta, A.; Ramos, R. Do renewable energy investments create local jobs? J. Public Econ. 2024, 239, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, R.; Couto, L.; Soria, R.; Szklo, A.; Lucena, A. Promoting social development in developing countries through solar thermal power plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.; Río, P.; Ruiz, P.; Nijs, W.; Politis, S. Analysing the influence of trade, technology learning and policy on the employment prospects of wind and solar energy deployment: The EU case. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 122, 109657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.; Aghahosseini, A.; Breyer, C. Job creation during the global energy transition towards 100% renewable power system by 2050. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Heptonstall, P.; Gross, R. Job creation in a low carbon transition to renewables and energy efficiency: A review of international evidence. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavard, C.; Göbel, J.; Schoch, N. Local Economic Impacts of Wind Power Deployment in Denmark. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2025, 88, 1679–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, A. Renewable energy and regional value: Identifying value added of public power producer and suppliers in japan. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 37, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, M.; Bristow, G.; Cowell, R. Wind Farms in Rural Areas: How Far Do Community Benefits from Wind Farms Represent a Local Economic Development Opportunity? J. Rural. Stud. 2011, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Mokaramian, E.; Anderson, S. The effects of the renewable energies penetration on the surplus welfare under energy policy. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabal, R. Towards a carbon-free society: Innovations in green energy for a sustainable future. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirma, V.; Neverauskienė, L.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Danilevičienė, I.; Tamošiūnienė, R. The Impact of Renewable Energy Development on Economic Growth. Energies 2024, 17, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Ngo, S.; Tran, P. Renewable Energy Integration for Sustainable Economic Growth: Insights and Challenges via Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, E.J.; Schwegman, D.J. Commercial wind energy installations and local economic development: Evidence from US counties. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Río, P.; Burguillo, M. An empirical analysis of the impact of renewable energy deployment on local sustainability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Nyuur, R.; Richmond, B. Renewable Energy Development as a Driver of Economic Growth: Evidence from Multivariate Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N.; Narayan, S. Does transitioning towards renewable energy accelerate economic growth? An analysis of sectoral growth for a dynamic panel of countries. Energy 2021, 235, 121290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Is renewable energy effective in promoting local economic development? The case of China. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 8, 025903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neverauskienė, L.; Dirma, V.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Danilevičienė, I. Assessing the Role of Renewable Energy in the Sustainable Economic Growth of the European Union. Energies 2025, 18, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dong, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, L. Renewable energy and economic growth: New insight from country risks. Energy 2022, 238, 121633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awijen, H.; Bélaïd, F.; Zaied, Y.; Hussain, N.; Lahouel, B. Renewable energy deployment in the MENA region: Does innovation matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Nguyen, C.; Park, D. Financing renewable energy development: Insights from 55 countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Rahman, S.; Khondaker, A.; Abubakar, I.; Aina, Y.; Hasan, M. Renewable energy utilization to promote sustainability in GCC countries: Policies 1537, drivers, and barriers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 20798–20814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Amin, A.; Nureen, N.; Saqib, N.; Wang, L.; Rehman, M. Assessing factors influencing renewable energy deployment and the role of natural resources in MENA countries. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koengkan, M.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Silva, N. Exploring the capacity of renewable energy consumption to reduce outdoor air pollution death rate in Latin America and the Caribbean region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1656–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masron, T.A.; Subramaniam, Y. Renewable energy and poverty–environment nexus in developing countries. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, Ş.E.C.; Sharp, J.L.; Anctil, A. Factors impacting diverging paths of renewable energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, M.; Kong, Y.; Manu, E.; Musah, M. Does policy integration in renewable energy deployment enhance environmental sustainability in Africa? Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2024, 20, 2439409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajo, R.; Cabeza, L.F. Renewable energy research and technologies through responsible research and innovation looking glass: Reflexions, theoretical approaches and contemporary discourses. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschamer, L.; Zhang, Q. Interactions of factors impacting implementation and sustainability of renewable energy sourced electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, S.F.; Bugallo, P.M.B. Evaluation of renewable energy system for sustainable development. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2021, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Yu, T.; Giannoccaro, G.; Mi, Y.; La Scala, M.; Nasab, M.R.; Wang, J. Improving reliability and stability of the power systems: A comprehensive review on the role of energy storage systems to enhance flexibility. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152738–152765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, A.; Eldar, D. Sustainable power solutions: Renewable energy & storage advancements. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.; Jasińska, E. Renewable revolution: A review of strategic flexibility in future power systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, K. Modern Energy Sources for Sustainable Buildings: Innovations and Energy Efficiency in Green Construction. Energies 2025, 18, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, V.; Christodoulou, C.; Zafeiropoulos, I.; Gonos, I.; Asprou, M.; Kyriakides, E. Evaluating the flexibility benefits of smart grid innovations in transmission networks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, T.; Morrison, G.M.; Breadsell, J.K.; Eon, C. A systematic literature review of the interplay between renewable energy systems and occupant practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, V.; Zafiropoulos, E.; Gonos, I.F.; Mladenov, V.; Chobanov, V. Power system studies in the clean energy era: From capacity to flexibility adequacy through research and innovation. In The International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Furtado, A.T.; Perrot, R. Innovation dynamics of the wind energy industry in South Africa and Brazil: Technological and institutional lock-ins. Innov. Dev. 2015, 5, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Examples |

|---|---|

| Objective | Income, health status, housing conditions, access to education |

| Subjective | Life satisfaction, emotional well-being, self-esteem |

| Material | Wealth/assets, income, employment |

| Non-material | Relationships, leisure, sense of security, cultural participation |

| Individual | Personal health, happiness, emotions |

| Societal | Social capital, community well-being, political stability |

| Domain | Examples |

|---|---|

| Economy | Income inequality, social benefits, unemployment, inflation, nature of work, job quality, working hours, indebtedness, commuting |

| Social relationships & community | Social participation, volunteering, membership in organizations, membership in religious organizations, trust, leadership/governance, marriage and personal relationships, family relationships, having children |

| Health | Physical health, psychological health, health behaviors, sleep |

| Education & care | Education, informal care |

| Local environment | Physical environment, urban spaces and planning, housing (living conditions), urbanization, pollution, crime, transport, traffic, climate |

| Personal characteristics | Age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, personality, material values |

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Search | Main steps: keywords identification; search database. Research scope: studies on renewable energy technology (RET) deployment and societal welfare. |

| Appraisal | Main steps: title/abstract/full text screening and article selection using PRISMA inclusion/exclusion criteria. |

| Synthesis | Main steps: data extraction and categorization. |

| Analysis | Main steps: analysis of the data, result comparison and conclusions. |

| Stages | Number |

| Records identified (Web of Science + Scopus) | 2430 |

| Duplicate records removed | 780 |

| Records screened (title/abstract) | 1650 |

| Full-text articles assessed for eligibility | 290 |

| Studies included in the review | 147 |

| Key Findings | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy deployment leads to significant reductions in GHG emissions | Supported by global, regional, and sectoral studies using robust modeling and empirical data | [41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,60,61,63,66,67,68,69,70] |

| Policy frameworks and financial development are critical for effective deployment and emissions reduction | Multiple cross-country and econometric studies show strong enabling effects | [41,69,71,72] |

| Integration with storage, electrification, and sector coupling amplifies emissions reductions | Scenario and life cycle analyses demonstrate synergistic effects | [48,61,64,65] |

| Local and sectoral challenges (e.g., intermittency, land use) can limit or complicate benefits | Some studies report region-specific or technology-specific limitations | [64,73,74] |

| Social acceptance and governance influence deployment rates and outcomes | Social science and policy studies highlight these as key drivers | [70,74] |

| Negative local impacts or rebound effects may occur if not managed | Limited but notable evidence of local trade-offs or unintended consequences | [73,75] |

| Key Findings | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy deployment significantly reduces air pollutants (SO2, NOX, PM2.5, CO) | Multiple large-scale, multi-country studies and policy analyses show consistent, significant reductions in key pollutants. | [76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

| Health and economic co-benefits of renewable energy often exceed policy costs | Monetized health benefits and reduced disease burden are well-documented and frequently surpass implementation costs. | [77,78,79,80] |

| Water quality and resource use improve with renewable energy adoption | Studies show reduced water use and pollution, especially in the power sector and desalination. | [79,84] |

| Benefits are regionally variable and depend on baseline pollution and policy context | Regional analyses and modeling show heterogeneity in benefits, with greatest gains in coal-dependent and polluted areas. | [77,78,80,81] |

| Policy integration, R&D, and governance are critical for maximizing benefits | Empirical and review studies highlight the moderating role of policy, investment, and governance. | [85,86,87,88] |

| Some renewable energy deployments may have unintended or limited effects on certain pollutants | Isolated studies note increases in N2O or limited reductions in CO/ozone, depending on context and technology. | [88,89,90] |

| Key Findings | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy deployment reduces air pollution and improves health outcomes | Multiple large-scale studies and reviews show consistent reductions in mortality and morbidity linked to air quality improvements | [77,78,80,90,93,94,100,101] |

| Health co-benefits of renewables often exceed the cost of deployment | Monetized health benefits (e.g., avoided deaths, reduced healthcare costs) frequently surpass levelized cost of renewables | [77,78,80] |

| Benefits are greatest in regions with high coal dependence and population density | Regional modeling and empirical studies show higher benefits where fossil fuel displacement is largest | [77,78,80] |

| Direct causal links between renewables and health can be confounded by social/policy factors | Some studies find weak or non-significant associations when controlling for other variables | [102,103,104] |

| Literature on health co-benefits is regionally concentrated and limited in developing countries | Systematic reviews note scarcity of studies outside US/Europe; developing regions understudied | [90,102] |

| Renewable energy alone cannot fully offset negative health impacts of economic growth | Some studies show economic growth can still drive environmental degradation despite renewables | [102,110] |

| Key Findings | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy deployment reduces energy poverty and improves energy security | Strong empirical evidence across multiple regions and income levels | [111,113,115,118,120,121,124,129,131,132,133,138] |

| Early-stage renewable deployment can temporarily increase energy poverty via higher prices | Observed in EU and some developing regions; effect diminishes as renewables mature | [111,112,113,114] |

| Solar and hydropower are most effective for rural energy poverty alleviation | Cost, scalability, and maintenance advantages in rural/remote areas | [51,120,121,127,132] |

| Governance quality and policy support are critical for maximizing benefits | Policy, regulatory, and institutional factors mediate outcomes | [74,111,112,113,114,115,145,146,147,148] |

| Barriers such as high capital costs and regulatory challenges persist | Frequently cited as obstacles to rapid deployment | [74,111,112,113,114,140,145,147] |

| In some contexts, renewables have not yet reduced energy poverty | Mixed or null findings in certain EU countries and early transition phases | [111,112,114] |

| Key Findings | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy deployment leads to net job creation | Multiple systematic reviews and empirical studies show positive net employment effects, especially in solar and wind sectors | [143,161,162,164,170,171,172] |

| Local economic development and income growth are positively impacted by renewables | Case studies and panel data analyses demonstrate increased local incomes, tax revenues, and public spending | [155,165,166,167,173] |

| Economic benefits vary by region, sector, and policy environment | Regional and sectoral analyses reveal heterogeneity in outcomes, with higher gains in supportive contexts | [45,56,117,143,160,162,164,171,174,175] |

| Community ownership and innovative financing enhance local benefits | Empirical evidence shows greater local retention of benefits with community models | [167] |

| Job quality, duration, and distribution can be uneven | Some studies report modest or short-term job gains, with challenges in retaining jobs locally | [160,164,165,167] |

| In some cases, renewable deployment may not significantly increase local employment | Certain studies find minor or no aggregate employment effects, especially in mature or capital-intensive projects | [165,167,176] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kunskaja, S.; Budzyński, A. Societal Welfare Implications of Solar and Renewable Energy Deployment: A Systematic Review. Solar 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010003

Kunskaja S, Budzyński A. Societal Welfare Implications of Solar and Renewable Energy Deployment: A Systematic Review. Solar. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKunskaja, Svetlana, and Artur Budzyński. 2026. "Societal Welfare Implications of Solar and Renewable Energy Deployment: A Systematic Review" Solar 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010003

APA StyleKunskaja, S., & Budzyński, A. (2026). Societal Welfare Implications of Solar and Renewable Energy Deployment: A Systematic Review. Solar, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010003