Modeling Site Suitability for Solar Farms in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study in Bibb County

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Results and Empirical Verification

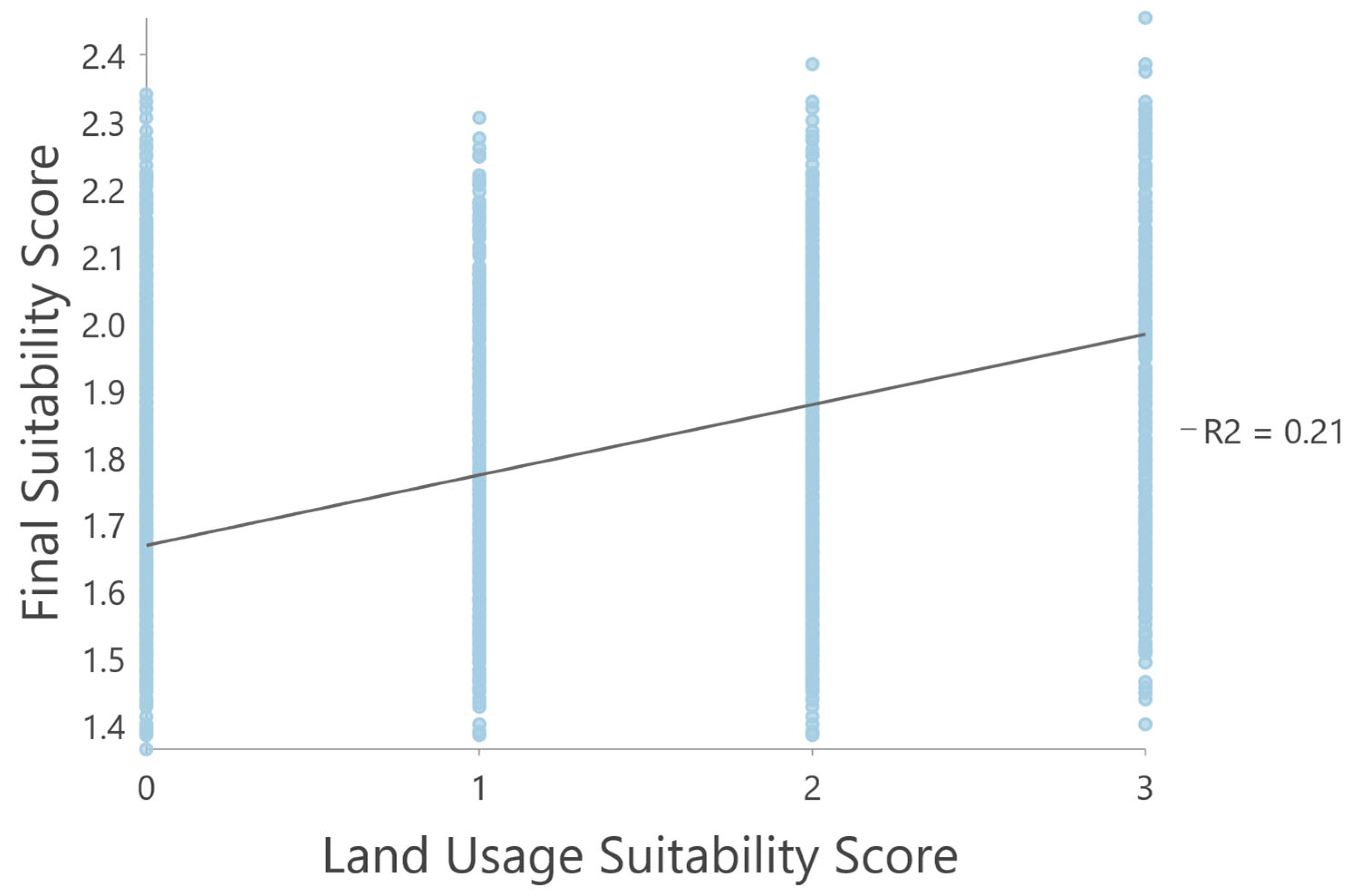

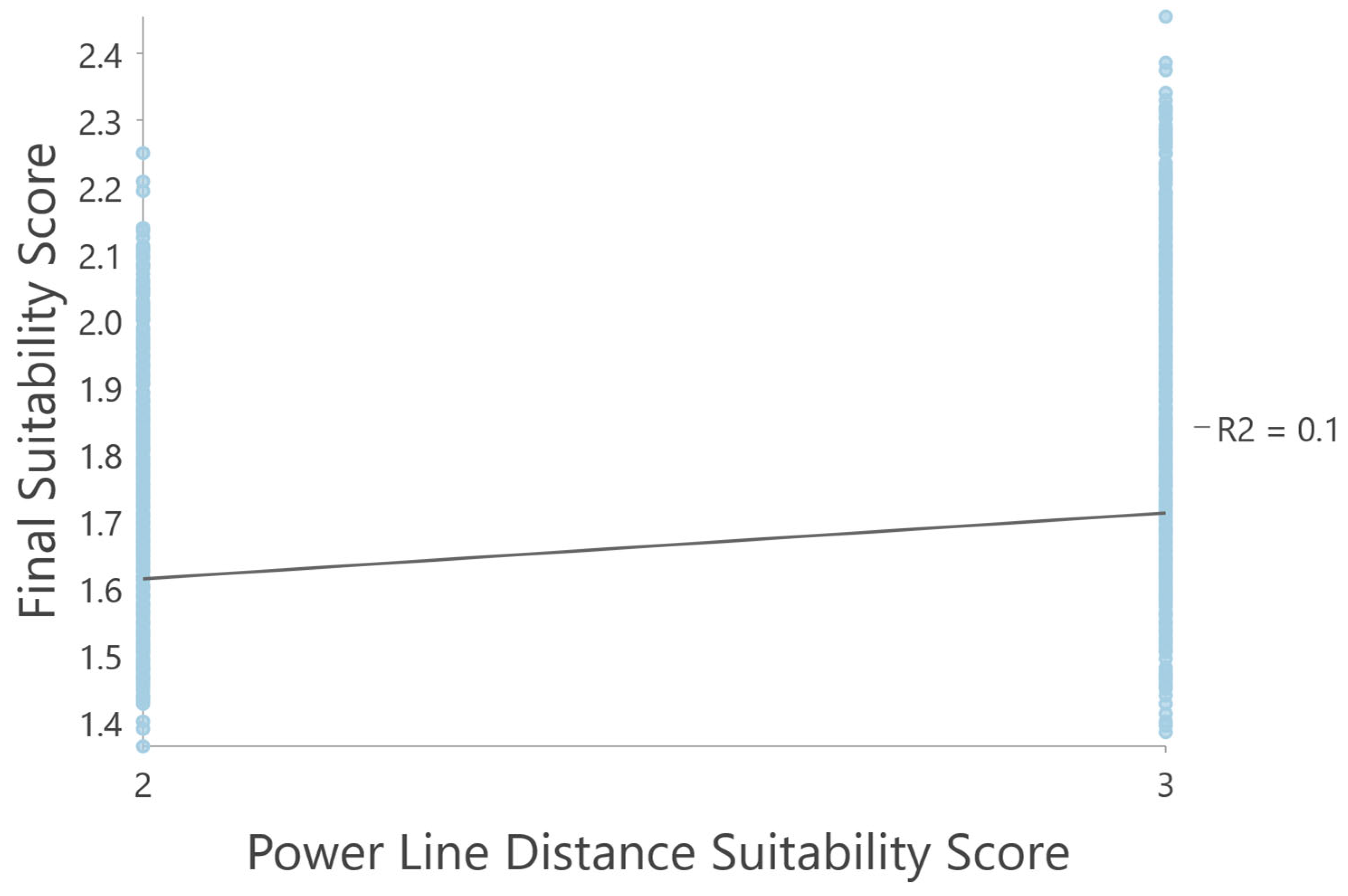

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Conclusions

Implications for Future Research and Policy

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P. Fossil Fuels; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute Fossil Fuels. Available online: https://eesi.org/topics/fossil-fuels/description (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Alley, R.B.B.; Berntsen, T.; Bindoff, N.L.L.; Chen, Z.; Chidthaisong, A.; Gregory, J.M.M.; Hegerl, G.C.C.; et al. Technical Summary. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K.B., Tignor, M., Miller, H.L., Eds.; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, P.; Unde, R.B.; Kern, C.; Jess, A. Production of Liquid Hydrocarbons with CO2 as Carbon Source Based on Reverse Water-Gas Shift and Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2013, 85, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyan, M. GIS-Based Solar Farms Site Selection Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Karapinar Region, Konya/Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy+ (LCOE+). Available online: https://lazard.com/media/uounhon4/lazards-lcoeplus-june-2025.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Lopez, A.; Roberts, B.; Heimiller, D.; Blair, N.; Porro, G. U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Noorollahi, E.; Fadai, D.; Akbarpour Shirazi, M.; Ghodsipour, S.H. Land Suitability Analysis for Solar Farms Exploitation Using GIS and Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP)—A Case Study of Iran. Energies 2016, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshangi, N.; Gharakhanlou, N.M.; Razin, S.R.G. Evaluation of Potential Sites in Iran to Localize Solar Farms Using a GIS-Based Fermatean Fuzzy TOPSIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 384, 135481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, J.R. Multicriteria GIS Modeling of Wind and Solar Farms in Colorado. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 2228–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Taweekun, J.; Techato, K.; Waewsak, J.; Gyawali, S. GIS Based Site Suitability Assessment for Wind and Solar Farms in Songkhla, Thailand. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisza, K. GIS-Based Suitability Modeling and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for Utility Scale Solar Plants in Four States in the Southeast U.S. Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, J.; Brownson, J.R.S. Solar Farm Suitability Using Geographic Information System Fuzzy Sets and Analytic Hierarchy Processes: Case Study of Ulleung Island, Korea. Energies 2016, 9, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.J.W.; Hudson, M.D. Regional Scale Wind Farm and Solar Farm Suitability Assessment Using GIS-Assisted Multi-Criteria Evaluation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Santos Arteaga, F.J.; Mohammadi, S.; Alimohammadi, M. A Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Spatial Decision Support System for Solar Farm Location Planning. Energy Strategy Rev. 2017, 18, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabaldır, C.; Yücel, M.A. GIS-Based Multicriteria Decision Analysis for Spatial Planning of Solar Photovoltaic Power Plants in Çanakkale Province, Turkey. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercan, E.; Eymen, A.; Urfalı, T.; Saracoglu, B.O. A Sustainable Framework for Spatial Planning of Photovoltaic Solar Farms Using GIS and Multi-Criteria Assessment Approach in Central Anatolia, Turkey. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ren, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, X. Optimizing Solar Photovoltaic Plant Siting in Liangshan Prefecture, China: A Policy-Integrated, Multi-Criteria Spatial Planning Framework. Sol. Energy 2024, 283, 113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, A.D.; Lamanna, E.; Nia, N.Y. Photovoltaics. In EPJ Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2020; Volume 246. [Google Scholar]

- Al Garni, H.Z.; Awasthi, A. Solar PV Power Plant Site Selection Using a GIS-AHP Based Approach with Application in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy Large-Scale Solar Siting Resources. Available online: https://energy.gov/eere/solar/large-scale-solar-siting-resources (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Roddis, P.; Carver, S.; Dallimer, M.; Norman, P.; Ziv, G. The Role of Community Acceptance in Planning Outcomes for Onshore Wind and Solar Farms: An Energy Justice Analysis. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, J.A.; Watson, J.E.M.; Lane, J.L.; Sonter, L.J.; Venter, O.; Atkinson, S.C.; Allan, J.R. Renewable Energy Development Threatens Many Globally Important Biodiversity Areas. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3040–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddis, P.; Roelich, K.; Tran, K.; Carver, S.; Dallimer, M.; Ziv, G. What Shapes Community Acceptance of Large-Scale Solar Farms? A Case Study of the UK’s First ‘Nationally Significant’ Solar Farm. Sol. Energy 2020, 209, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; Sims, C.A.; Christian, J.M. Evaluation of Glare at the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System. Energy Procedia 2015, 69, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xue, S.; Yang, T.; Yang, Q. Research on Influencing Factors of Line Loss Rate of Regional Distribution Network Based on Apriori-Interpretative Structural Model. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Ni, B. Line Loss Analysis and Calculation of Electric Power Systems; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Singapore, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-86723-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjgar, B.; Niccolai, A.; Leva, S. Where Can Solar Go? Assessing Land Availability for PV in Italy Under Regulatory Constraints. Solar 2025, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C.; Kaya, İ.; Cebi, S. A Comparative Analysis for Multiattribute Selection among Renewable Energy Alternatives Using Fuzzy Axiomatic Design and Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process. Energy 2009, 34, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwarzai, M.A.; Nagasaka, K. Utility-Scale Implementable Potential of Wind and Solar Energies for Afghanistan Using GIS Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabazz, S. Georgia Solar Incentives, Tax Credits, Rebates and Solar Panel Cost Guide. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/home-improvement/solar/georgia-solar-incentives/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Fthenakis, V.; Mason, J.E.; Zweibel, K. The Technical, Geographical, and Economic Feasibility for Solar Energy to Supply the Energy Needs of the US. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy Photovoltaic Solar Resource: United States and Germany. Available online: https://thurstonenergy.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/PVMap_USandGermany.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Mastering ArcGIS Pro Tutorial Data. Available online: https://highered.mheducation.com/sites/1264091206/student_view0/arcgis_data_sets.html (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Gross, S. Renewables, Land Use, and Local Opposition in the United States. Available online: https://brookings.edu/articles/renewables-land-use-and-local-opposition-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Williams, D. Spread of Solar Farms in Georgia about to Get Legislative Scrutiny. Available online: https://capitol-beat.org/2024/06/spread-of-solar-farms-in-georgia-about-to-get-legislative-scrutiny/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Williams, D. Giant Solar Farms Proving a Mixed Bag for Rural Georgia. Available online: https://gpb.org/news/2022/10/25/giant-solar-farms-proving-mixed-bag-for-rural-georgia (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Kann, D. Solar Company Settles with Georgia Couple in Case of Muddy Runoff. Available online: https://ajc.com/news/business/silicon-ranch-settles-with-georgia-couple-in-muddy-runoff-case/VFW4S4KO3ZF6VB6PGROV2YCERU/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Adams, J. Solar Renewable Resource. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=3743e316e11b4f0f9628bd842b8eb40a (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Esri Ground Surface Elevation—30m. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=0383ba18906149e3bd2a0975a0afdb8e (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Esri USA NLCD Land Cover. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=3ccf118ed80748909eb85c6d262b426f (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Esri US Federal Data Aviation Facilities. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=88c147b65ced41d4a1ecb8dac2e9e7e4 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Esri US Federal Data Transportation. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=f42ecc08a3634182b8678514af35fac3 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Mungroo, A. Georgia Power Grid Map. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=f9ab31434cfb49ca86fb2217dbb9bc4a (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Cordero, R.R.; Feron, S.; Damiani, A.; Sepúlveda, E.; Jorquera, J.; Redondas, A.; Seckmeyer, G.; Carrasco, J.; Rowe, P.; Ouyang, Z. Surface Solar Extremes in the Most Irradiated Region on Earth, Altiplano. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1206–E1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckowski, J.; Sałabun, W. Sensitivity Analysis Approaches in Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: A Systematic Review. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Khan, S. Spatial Sensitivity Analysis of Multi-Criteria Weights in GIS-Based Land Suitability Evaluation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. Solar Power Plants in the U.S. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=4ca2031ccbb14ec3b5faaf36938a0a2d (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Saaty, T.L. How to Make a Decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. Using the Delphi Method to Establish Expert Consensus, 1st ed.; Advancing Methods for Interdisciplinarity in the Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2025; ISBN 978-981-96-8356-7. [Google Scholar]

- Laasri, S.; El Hafidi, E.M.; Mortadi, A.; Chahid, E.G. Solar-Powered Single-Stage Distillation and Complex Conductivity Analysis for Sustainable Domestic Wastewater Treatment. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2024, 31, 29321–29333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA Geospatial EPA Facility Registry Service: Integrated Compliance Information System (ICIS) Wastewater Treatment Plants. Available online: https://arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=0895b107f9184e7cb31707767b506a64 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

| Criterion | Description | Original Weight | Modified Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| GHI | The solar irradiance received by the area, measured as global horizontal irradiance (GHI) in kWh/m2/d | 0.3578 | 0.4646 |

| Elevation | The elevation of the area, measured in meters | 0.0076 | 0.0099 |

| Slope | The slope of the area, measured as a percentage | 0.0532 | 0.0691 |

| Land Usage | The current usage or coverage of the area | 0.1163 | 0.1510 |

| Urban Distance | The distance to the nearest urban residential area, measured in meters | 0.0201 | 0.0261 |

| Rural Distance | The distance to the nearest rural residential area, measured in meters | 0.0100 | 0.0130 |

| Wetland Distance | The distance to the nearest wetland, measured in meters | 0.0423 | 0.0549 |

| Forest Distance | The distance to the nearest forest, measured in meters | 0.0060 | 0.0078 |

| Airport Distance | The distance to the nearest airport, measured in meters | 0.0423 | 0.0549 |

| Road Distance | The distance to the nearest primary or secondary road, measured in meters | 0.0286 | 0.0371 |

| Power Line Distance | The distance to the nearest power transmission line, measured in meters | 0.0859 | 0.1115 |

| Criterion | Dataset Name | Source |

|---|---|---|

| GHI | Solar Renewable Resource | [39] |

| Elevation | Ground Surface Elevation—30 m | [40] |

| Slope | ||

| Land Usage | USA NLCD Land Cover | [41] |

| Urban Distance | ||

| Rural Distance | ||

| Wetland Distance | ||

| Forest Distance | ||

| Airport Distance | Aviation Facilities | [42] |

| Road Distance | Transportation | [43] |

| Power Line Distance | Georgia Power Grid Map | [44] |

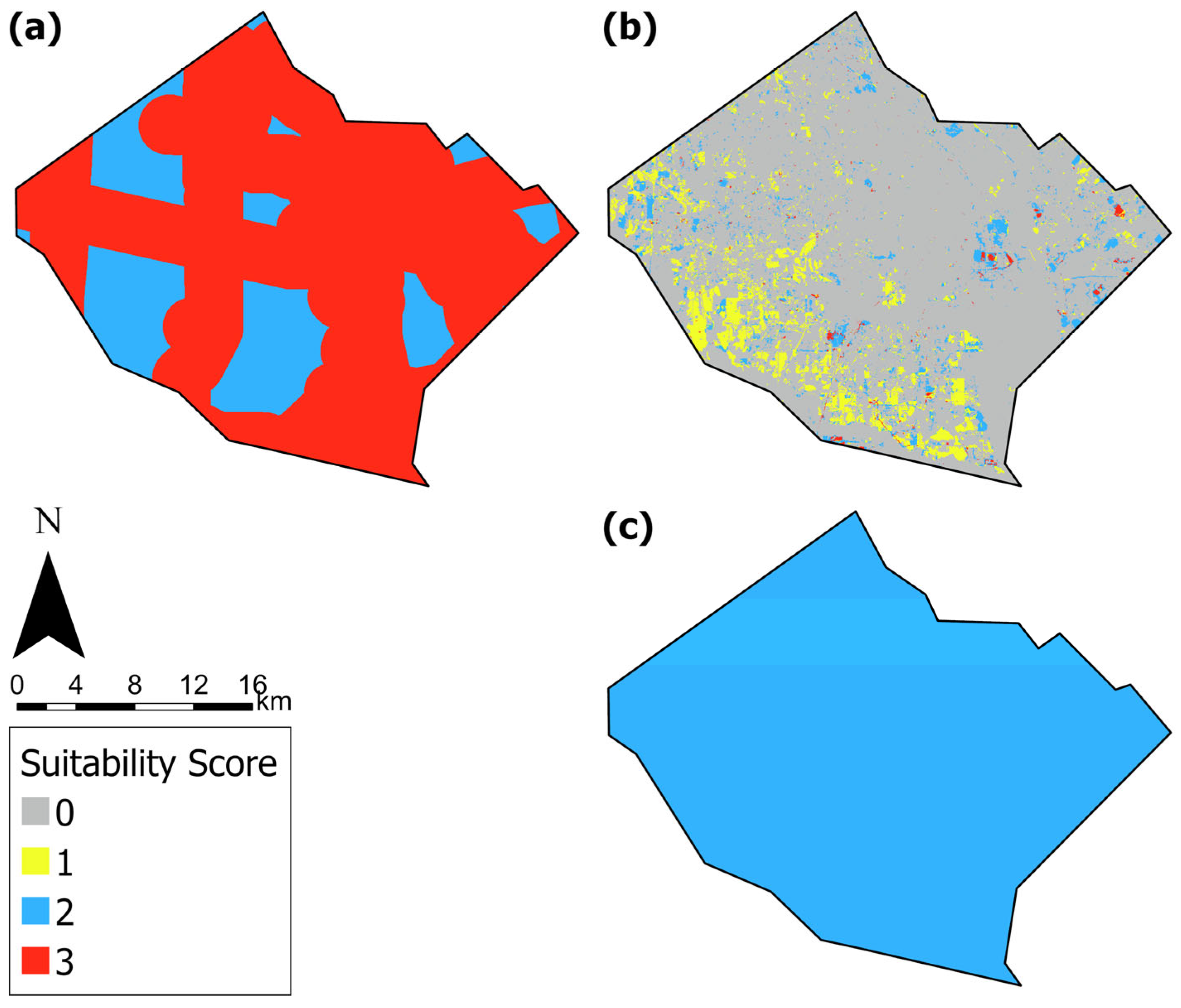

| Criterion | Unit | Highly Suitable (3) | Moderately Suitable (2) | Low Suitability (1) | Not Suitable (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHI | kWh/m2/d | >5 | >4.5 | >3.5 | ≤3.5 |

| Elevation | m | <50 | <100 | <200 | ≥200 |

| Slope | % | <1% | <3% | <5% | ≥5% |

| Land Usage | m | Barren Land | Shrub/Scrub, Grassland/Herbaceous | Pasture/Hay, Cultivated Crops | All other codes |

| Urban Distance | m | >1500 | >1000 | >500 | ≤500 |

| Rural Distance | m | >1500 | >1000 | >500 | ≤500 |

| Wetland Distance | m | >1000 | >500 | >400 | ≤400 |

| Forest Distance | m | >1500 | >1250 | >1000 | ≤1000 |

| Airport Distance | m | >2000 | >1500 | >1000 | ≤1000 |

| Road Distance | m | <2000 | <5000 | <10,000 | ≥10,000 |

| Power Line Distance | m | <2000 | <5000 | <10,000 | ≥10,000 |

| Criterion | Land Cover Codes |

|---|---|

| Urban Distance | Developed medium intensity, Developed high intensity |

| Rural Distance | Developed open space, Developed low intensity |

| Wetland Distance | Woody wetlands, Emergent herbaceous wetlands |

| Forest Distance | Deciduous forest, Evergreen forest, Mixed forest |

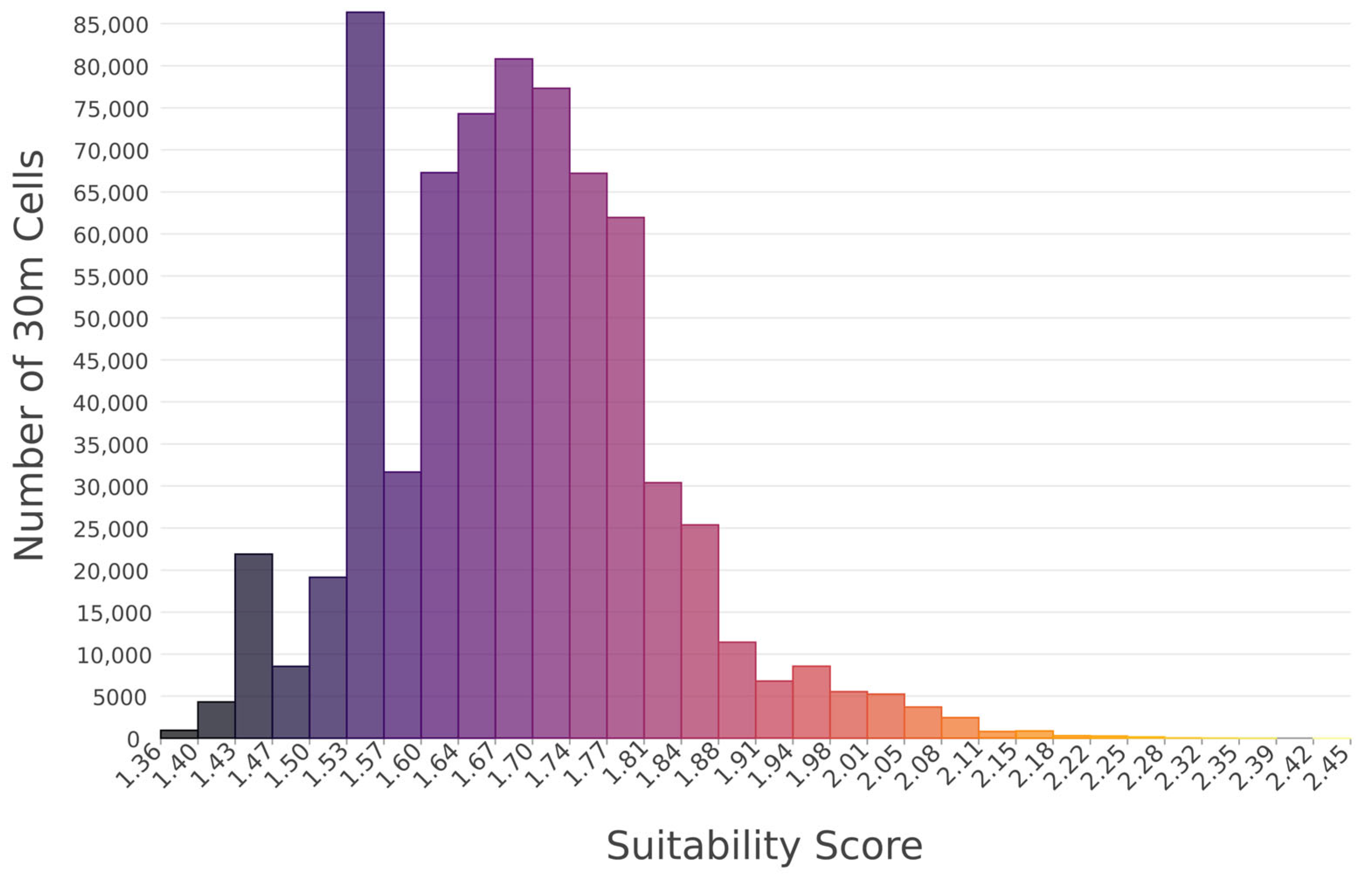

| Classification Rank | Range of Values | Area (km2) | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsuitable | 0.0–0.5 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Low | 0.5–1.0 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Moderate-to-Low | 1.0–1.5 | 32.10 | 5% |

| Moderate | 1.5–2.0 | 587.40 | 93% |

| Moderate-to-High | 2.0–2.5 | 13.67 | 2% |

| High | 2.5–3.0 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Criterion | Negative Threshold | Positive Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| GHI | −2% | +2% |

| Elevation | TNR | TNR |

| Slope | −7% | +12% |

| Land Usage | −3% | +3% |

| Urban Distance | −18% | +18% |

| Rural Distance | TNR | TNR |

| Wetland Distance | TNR | +9% |

| Forest Distance | TNR | TNR |

| Airport Distance | −9% | +8% * |

| Road Distance | −13% | +13% |

| Power Line Distance | −7% | +12% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nash, E.; Sadeghvaziri, E. Modeling Site Suitability for Solar Farms in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study in Bibb County. Solar 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010002

Nash E, Sadeghvaziri E. Modeling Site Suitability for Solar Farms in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study in Bibb County. Solar. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Ezra, and Eazaz Sadeghvaziri. 2026. "Modeling Site Suitability for Solar Farms in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study in Bibb County" Solar 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010002

APA StyleNash, E., & Sadeghvaziri, E. (2026). Modeling Site Suitability for Solar Farms in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study in Bibb County. Solar, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar6010002