Generalized Interval-Valued Convexity in Fractal Geometry

Abstract

1. Introduction and Preliminaries

2. Preliminaries

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- .

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- is the additive identity of such that ,

- 4.

- For any then there exists such that .

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- then for each we have

- 4.

- For each there exists such that .

- is a field.

- The order relation ≤ on is defined as follows ⇔ in . Then, is an ordered field.

- 1.

- If , then

- 2.

- If , then

- 3.

- If , then

3. Main Results

- 1.

- Commutativity under addition and multiplications:

- 2.

- Associativity under addition and multiplications:

- 3.

- Existence of both identities:

- 4.

- Associativity:

- 5.

- First distributive law:

- 6.

- Second distributive law:

- 7.

- In general, distributive law does not hold. One can easily check that for , and , distributive property does not hold.

- 8.

- Inverse does not exist. One can verify that for , the inverse does not exist.

Local Integration

4. Interval-Valued Generalized Convex Functions

- Conversely, suppose that and ; then,

- , then

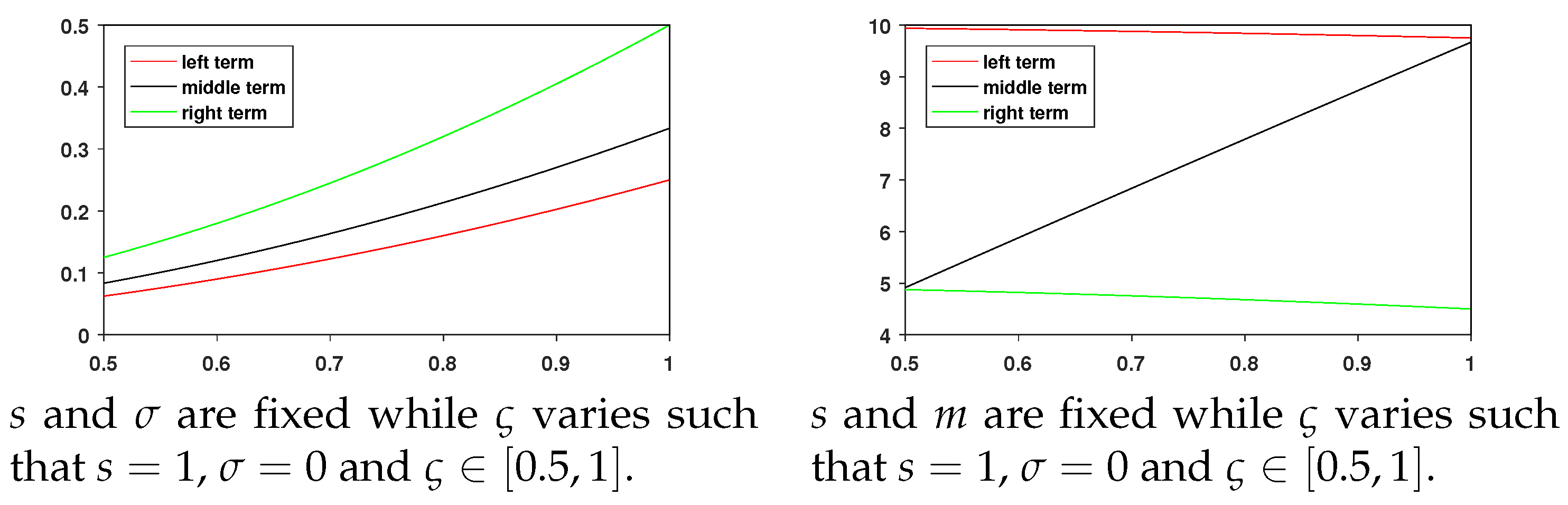

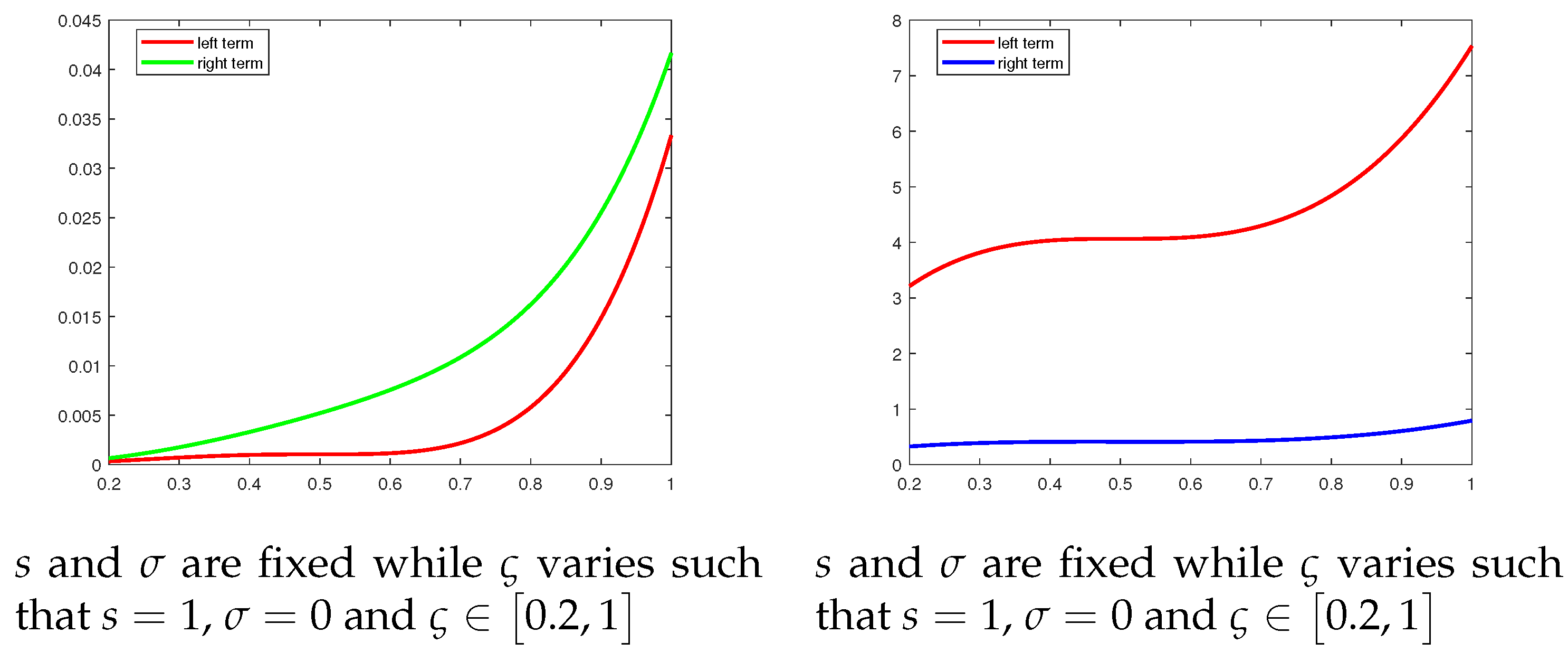

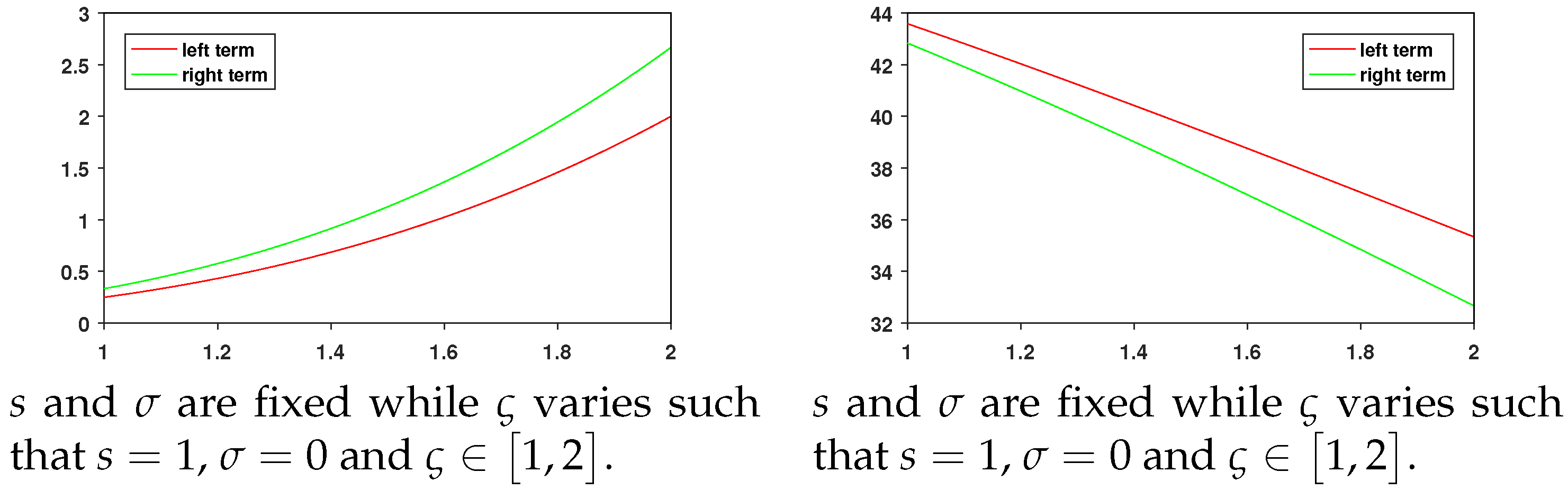

5. Visual Analysis

| Values of | Left Term | Middle Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.08333 | 0.1250 |

| 0.6 | 0.0900 | 0.1200 | 0.1800 |

| 0.7 | 0.1225 | 0.1633 | 0.2450 |

| 0.8 | 0.1600 | 0.2133 | 0.3200 |

| 0.9 | 0.2025 | 0.2700 | 0.4050 |

| 1 | 0.2500 | 0.3333 | 0.5000 |

| Values of | Left Term | Middle Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 9.9375 | 4.9167 | 4.8750 |

| 0.6 | 9.9100 | 5.8800 | 4.8200 |

| 0.7 | 9.8775 | 6.8367 | 4.7550 |

| 0.8 | 9.8400 | 7.7867 | 4.6800 |

| 0.9 | 9.7975 | 8.7300 | 4.5950 |

| 1 | 9.7500 | 9.6667 | 4.5000 |

| Values of | Left Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.000331 | 0.000653 |

| 0.3 | 0.000711 | 0.001755 |

| 0.4 | 0.000981 | 0.003307 |

| 0.5 | 0.001042 | 0.005208 |

| 0.6 | 0.001152 | 0.007560 |

| 0.7 | 0.002172 | 0.010862 |

| 0.8 | 0.005803 | 0.016213 |

| 0.9 | 0.014823 | 0.025515 |

| Values of | Left Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.000331 | 0.000653 |

| 0.3 | 0.000711 | 0.001755 |

| 0.4 | 0.000981 | 0.003307 |

| 0.5 | 0.001042 | 0.005208 |

| 0.6 | 0.001152 | 0.007560 |

| 0.7 | 0.002172 | 0.010862 |

| 0.8 | 0.005803 | 0.016213 |

| 0.9 | 0.014823 | 0.025515 |

| Values of | Left Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 0.3328 | 0.4437 |

| 1.2 | 0.4320 | 0.5760 |

| 1.3 | 0.5493 | 0.7323 |

| 1.4 | 0.6860 | 0.9147 |

| 1.5 | 0.8438 | 1.1250 |

| 1.6 | 1.0240 | 1.3653 |

| 1.7 | 1.2283 | 1.6377 |

| 1.8 | 1.4580 | 1.9440 |

| 1.9 | 1.7148 | 2.2863 |

| Values of | Left Term | Right Term |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 42.8161 | 41.9187 |

| 1.2 | 42.0320 | 40.9760 |

| 1.3 | 41.2326 | 40.0073 |

| 1.4 | 40.4193 | 39.0147 |

| 1.5 | 39.5938 | 38.0000 |

| 1.6 | 38.7573 | 36.9653 |

| 1.7 | 37.9116 | 35.9127 |

| 1.8 | 37.0580 | 34.8440 |

| 1.9 | 36.1981 | 33.7613 |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, R.E. Interval Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1966; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chalco-Cano, Y.; Flores-Franulič, A.; Román-Flores, H. Ostrowski type inequalities for interval-valued functions using generalized Hukuhara derivative. Comput. Appl. Math. 2012, 31, 457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, T.M.; Román-Flores, H. Some integral inequalities for fuzzy-interval-valued functions. Inf. Sci. 2017, 420, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ye, G.; Zhao, D.; Liu, W. Some integral inequalities for log-h-convex interval-valued functions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86739–86745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, T.; Rashid, S.; Khan, H.; Chu, Y.M. On new fractional integral inequalities for p-convexity within interval-valued functions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, H.; Tunç, T.; Sarikaya, M.Z. Fractional Hermite-Hadamard-type inequalities for interval-valued functions. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2020, 148, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Mohsin, B.; Javed, M.Z.; Awan, M.U.; Kashuri, A. On Some New AB-Fractional Inclusion Relations. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, H.; Ali, M.A.; Budak, H. Hermite-Hadamard-type inequalities for interval-valued coordinated convex functions involving generalized fractional integrals. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2021, 44, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.B.; Noor, M.A.; Mohammed, P.O.; Guirao, J.L.G.; Noor, K.I. Some integral inequalities for generalized convex fuzzy-interval-valued functions via fuzzy Riemann integrals. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2021, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.W.V. Sur les fonctions convexes et les inégalités entre les valeurs moyennes. Acta Math. 1906, 30, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadamard, J. Étude sur les propriétés des fonctions entières et en particulier d’une fonction considérée par Riemann. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1893, 9, 171–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hermite, C. Cours d’Analyse de l’École Polytechnique. Première Partie; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1873; p. 478. [Google Scholar]

- Bin-Mohsin, B.; Rafique, S.; Cesarano, C.; Javed, M.Z.; Awan, M.U.; Kashuri, A.; Noor, M.A. Some General Fractional Integral Inequalities Involving LR-Bi-Convex Fuzzy Interval-Valued Functions. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, A.; Wang, Y.; Ali, Z.; Hussain, R.; Furuichi, S. Exploring properties and inequalities for geometrically arithmetically-Cr-convex functions with Cr-order relative entropy. Inf. Sci. 2024, 662, 120219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, W.; Breaz, D.; Abbas, M.; Cotîrlă, L.-I.; Khan, Z.A.; Rapeanu, E. Hyers-Ulam Stability of 2D-Convex Mappings and Some Related New Hermite-Hadamard, Pachpatte, and Fejér Type Integral Inequalities Using Novel Fractional Integral Operators via Totally Interval-Order Relations with Open Problem. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Nwaeze, E.R.; Khan, M.B.; Hakami, K.H. New Version of Fractional Pachpatte-Type Integral Inequalities via Coordinated ℏ-Convexity via Left and Right Order Relation. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-J. Advanced Local Fractional Calculus and Its Applications; World Science Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; WH Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, H.; Sui, X. Generalized s-convex functions on fractal sets. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, 2014, 254737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya, M.Z.; Budak, H. Generalized Ostrowski type inequalities for local fractional integrals. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2017, 145, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.A.; Noor, K.I.; Iftikhar, S.; Awan, M.U. Fractal integral inequalities for harmonic convex functions. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2018, 12, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Q. Hadamard type local fractional integral inequalities for generalized harmonically convex functions and applications. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2020, 43, 5776–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xu, R. Some new Hermite-Hadamard type inequalities for generalized harmonically convex functions involving local fractional integrals. AIMS Math. 2021, 6, 10679–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Rasheed, T.; Shaokat, S. Generalized Hermite-Hadamard type inequalities for generalized F-convex function via local fractional integrals. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 168, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R.V.; Sanabria, J.E. Strongly convexity on fractal sets and some inequalities. Proyecciones 2020, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, H.; Du, T. Fejér-Hermite-Hadamard type inequalities involving generalized h-convexity on fractal sets and their applications. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 131, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman-Mursaleen, M.; Nasiruzzaman, M.; Rao, N. On the approximation of Szasz-Jakimovski-Leviatan beta type integral operators enhanced by Appell polynomials. Iran. J. Sci. 2025, 49, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Farid, M.; Raiz, M. On the approximations and symmetric properties of Frobenius–Euler–Simşek polynomials connecting Szasz operators. Symmetry 2025, 17, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Khalid, A.; Karaca, Y.; Chu, Y.M. Revisiting Fejer-Hermite-Hadamard type inequalities in fractal domain and applications. Fractals 2022, 30, 2240133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Javed, M.Z.; Awan, M.U.; Zhao, D.; Khan, A.G.; Jäntschi, L. Generalized Interval-Valued Convexity in Fractal Geometry. AppliedMath 2026, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010005

Javed MZ, Awan MU, Zhao D, Khan AG, Jäntschi L. Generalized Interval-Valued Convexity in Fractal Geometry. AppliedMath. 2026; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaved, Muhammad Zakria, Muhammad Uzair Awan, Dafang Zhao, Awais Gul Khan, and Lorentz Jäntschi. 2026. "Generalized Interval-Valued Convexity in Fractal Geometry" AppliedMath 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010005

APA StyleJaved, M. Z., Awan, M. U., Zhao, D., Khan, A. G., & Jäntschi, L. (2026). Generalized Interval-Valued Convexity in Fractal Geometry. AppliedMath, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath6010005