1. Introduction

Chemical graph theory is a versatile and powerful field with numerous applications in materials science and chemistry. It provides a mathematical framework for understanding the behaviour and structure of chemical molecules. This framework is used in computational chemistry, cheminformatics, materials design, and drug discovery. Topological indices—mathematical values applied in studies such as QSPR/QSAR—are an essential component of this theory [

1,

2,

3]. These indices are particularly valuable for estimating the potency of drug candidates and have attracted significant attention in the field [

4,

5,

6].

A highly effective method for converting chemical structures into numerical values that correlate with physical properties is the use of topological indices. Among the various indices studied to date, many practical ones are based on distances or molecular configuration. In 1947, Wiener introduced the first distance-based index, now known as the Wiener index. His work demonstrated a strong relationship between the boiling point of alkanes and certain graph-theoretical parameters, which motivated the development of additional distance-type topological indices [

7].

Topological indices play a central role in quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) and quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) analyses, both of which support the development and optimisation of pharmaceutical compounds [

8,

9]. These analyses rely on molecular structure to predict physical, chemical, and biological characteristics. Degree-based indices such as the Atom–Bond Connectivity (ABC), Randić (RA), Geometric–Arithmetic (GA), Sum Connectivity (S), and Zagreb indices have been widely applied in modelling and characterising chemical compounds [

10,

11,

12]. By comparing these indices with experimentally measured properties, researchers gain valuable insights into how molecular structure influences parameters such as molar volume, boiling point, and molecular complexity [

13,

14].

Recent developments have expanded the applicability of topological indices with the introduction of new graph degrees, such as the Ev-degree and Ve-degree. These graph invariants have enhanced the descriptive power of TIs, enabling the more accurate modelling of complex compounds. For example, antibiotic structures have been extensively investigated through indices based on reverse degrees. In drug development, topological indices are increasingly used to model and characterise drug molecules, aiding in the prediction of toxicity, side effects, and bioactivity [

15,

16,

17]. By analysing the molecular graphs [

18,

19] of drug candidates, researchers can identify promising compounds, anticipate potential risks, and accelerate the discovery of new therapeutics—significantly reducing the need for time-consuming laboratory experiments.

Despite their demonstrated usefulness, a major challenge in applying topological indices in QSPR lies not in their numerical performance but in their qualitative nature [

20,

21]. Although both classical and advanced chemometric methods confirm that topological indices can effectively characterise various physicochemical, biological, environmental, and toxicological properties of organic compounds, they remain fundamentally qualitative. Unlike traditional chemical descriptors derived from geometric or quantum-mechanical principles, TIs rely on an ad hoc graph representation of molecules. Similar criticisms have been raised in the graph-based modelling of other systems, such as neural networks, social structures, and transportation networks [

22,

23]. While such systems can often be described topologically, molecular systems face additional scrutiny due to the availability of quantum-mechanical modelling approaches that appear more physically grounded.

Although several attempts have been made to clarify the theoretical nature of topological indices, none can yet be considered a true physical derivation. In this project, we explore two complementary approaches found in the literature: one employing chemometric techniques to analyse the behaviour of these descriptors, and the other relying on mathematical—particularly algebraic—methods to investigate the underlying invariants on which TIs are based. The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology used in this study.

Section 3 introduces the molecular graphs of drugs for coronary artery disease (CAD) along with the corresponding topological indices.

Section 4 describes the machine learning methods employed.

Section 5 reports the numerical results and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study and highlights the key findings.

2. Methodology

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting millions annually. It is caused by the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries, leading to reduced blood flow, myocardial ischaemia, heart attacks, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death. Key risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle. Research has extensively studied the cellular, molecular, and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CAD, including endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and plaque instability.

The management of CAD relies on drugs such as Isinopril, Amlodipine, Xarelto, Brilinta, Perindopril, Isoxsurprine, Azilsartan, and Metolazone. These medications act by lowering cholesterol, preventing platelet aggregation, and reducing myocardial oxygen demand. Their therapeutic efficacy and safety are influenced by dosage, selectivity, patient comorbidities, and molecular structure. Understanding the structural properties of these drugs is crucial to rational drug design, as it guides the development of molecules with improved potency, selectivity, and reduced side effects. Computational approaches can further leverage this structural information to predict drug behaviour, optimise efficacy, and accelerate the drug discovery process.

In this study, we integrate chemical graph theory with machine learning (ML) to analyse and predict the efficacy of CAD drugs. Machine learning has been successfully applied in diverse domains, including cybersecurity and IoT-based threat mitigation, demonstrating its versatility for predictive modelling [

24]. Molecular structures are represented as chemical graphs, from which topological descriptors are extracted to capture connectivity and structural features. These descriptors serve as input to supervised ML models, enabling the identification of structural factors that influence drug performance. Our approach demonstrates that graph-theoretical descriptors can enhance prediction accuracy and provide mechanistic insights, offering a robust, interpretable, and scalable framework for CAD drug discovery. The main contributions of this study are depicted in

Figure 1.

3. Molecular Graphs of Coronary Artery Disease Drugs and Graphical Indices

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common type of heart disease, characterised by the narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries due to the buildup of plaque (atherosclerosis). This condition reduces blood flow to the heart muscle, leading to chest pain (angina), shortness of breath, or even heart attacks. Risk factors include high cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle.

A variety of drugs are used to manage CAD by targeting different aspects of the disease. For example, Lisinopril and Perindopril are ACE inhibitors that lower blood pressure and reduce heart strain, while Amlodipine helps relax and widen blood vessels as a calcium channel blocker. Xarelto and Brilinta are antithrombotic agents that prevent blood clots, reducing the risk of stroke or heart attack. Azilsartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), is effective in lowering blood pressure, and Metolazone, a diuretic, helps manage fluid retention. Additionally, Isoxsuprine improves blood flow by relaxing vascular smooth muscles. These drugs play a vital role in reducing CAD symptoms, improving heart function, and preventing complications. The molecular structures of drugs for coronary artery disease treatment are depicted in

Figure 2.

In

Table 1, we present the physical and characteristic properties of the drugs used in the treatment of coronary artery disease.

3.1. Graphical Indices

Molecular descriptors play a significant role in medicine, particularly in drug design and discovery. By applying degree-based topological indices to drugs used in disease therapy, researchers can analyse their structural features and establish connections to their biological activity. In this context, we will discuss some of these indices with respect to the previously mentioned drugs.

A molecular graph G is an ordered pair of , which denotes the vertices (atoms), and , which represents the edges (bonds between atoms). The degree of a vertex m is denoted by and defined as the number of edges connected to it. Molecular graphs can be analysed using topological indices, which serve as molecular descriptors to evaluate the physical and chemical properties of molecules and facilitate mathematical analyses.

Several graphical indices have been developed to study molecular structures. We discuss a few prominent indices as follows.

3.1.1. Atom–Bond Connectivity (ABC) Index

The Atom–Bond Connectivity index,

, is utilised to evaluate the stability of alkanes and the strain energy of cycloalkanes. Proposed by Erciyes [

25], the index is defined as

3.1.2. Zagreb Indices

The Zagreb indices are well-known molecular descriptors initially introduced by Gutman and Trinajstić [

12]. These indices are used to explore the relationship between the total

-electron energy and molecular structure. The first and second Zagreb indices are defined as

3.1.3. Randić Index

Proposed by Randić in 1975 [

26], the Randić index,

, measures the branching complexity of molecular structures and is given by

3.1.4. Sum Connectivity Index

The Sum Connectivity index, proposed by Zhou and Trinajstić [

27], is expressed as

3.2. Geometric–Arithmetic Index

Vujošević et al. [

28] introduced the geometric–arithmetic index,

, which is defined as

3.3. Harmonic Index

Proposed by Fajtlowicz [

5], the harmonic index,

, is represented as

3.4. Hyper Zagreb Index

A modified version of the Zagreb index, the hyper Zagreb index, was introduced by Shirdel et al. [

29] and is given by

3.5. Forgotten Index

The forgotten index,

, proposed by Furtula and Gutman [

30], is widely used in QSAR/QSPR studies. It is defined as

These indices provide valuable insights into molecular structure and behaviour, enabling researchers to correlate structural features with physical, chemical, and biological properties. The computed molecular descriptors for the candidate drugs are summarised in

Table 2.

4. Machine Learning Method

Machine learning provides a powerful framework for analysing complex chemical and biological data by detecting nonlinear patterns that traditional methods may not capture. It enhances prediction accuracy through models that learn directly from molecular descriptors, enabling the identification of key structural features that influence drug performance. By leveraging these capabilities, machine learning supports faster, more reliable, and data-driven approaches to drug discovery and development.

This study integrates graph-theoretical methods with machine learning techniques to support drug design for coronary artery disease (CAD). The overall workflow is structured as follows: Drug molecules and target proteins are first represented as molecular graphs, where atoms correspond to nodes and chemical bonds to edges. From these representations, a broad set of topological and structural descriptors is extracted to quantitatively characterise each molecule. Machine learning models, including linear regression model and Random Forest (RF), are subsequently trained on the extracted graph-based features.

Linear regression models: Regression techniques, particularly linear regression, are utilised to quantify the relationship between molecular descriptors and drug–target binding affinity. Linear regression provides a transparent and analytically tractable modelling framework, making it a widely used baseline in quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) studies. Its closed-form solution via the normal equation enables efficient estimation of regression coefficients, while its interpretability allows researchers to identify key structural features that contribute to binding strength. Despite its simplicity, linear regression has demonstrated strong predictive utility in chemoinformatics, especially when molecular descriptors exhibit linear or near-linear associations with biological activity [

31,

32]. Furthermore, linear models serve as essential benchmarks for evaluating the performance of more complex machine learning algorithms. The linear regression model is a simple and widely used approach to predict a response variable

y based on a set of input features. It assumes that the relationship between the response and the predictors is linear, which can be expressed as

In this equation, represents the predicted value of the response, is the intercept which corresponds to the predicted value when all predictors are zero, denotes the j-th input feature, and is the coefficient that measures how much changes when increases by one unit while keeping other variables constant. Here, p is the total number of predictors included in the model. The coefficients are estimated from the training dataset, which consists of observed pairs , by minimising the sum of squared differences between the observed responses and the predicted values. This process ensures that the model captures the linear trends in the data as accurately as possible.

Random Forest (RF): The Random Forest algorithm is employed as a more flexible nonlinear model capable of capturing intricate interactions among structural descriptors. RF constructs an ensemble of decision trees, each trained on bootstrapped subsets of the data and descriptor space, thereby reducing variance and mitigating overfitting [

33]. This ensemble strategy enables RF to model heterogeneous molecular patterns that may not be captured by linear methods. In drug discovery, RF has shown strong performance in both regression and classification settings, particularly in predicting bioactivity, physicochemical properties, and drug–target associations [

34,

35]. Its ability to quantify feature importance also provides valuable insights into which graph-theoretical descriptors most strongly influence predicted binding affinity. This makes RF an effective tool not only for prediction but also for mechanistic interpretation of molecular behaviour. The Random Forest prediction is given by

where

is the input feature vector for which the prediction is made,

is the set of random vectors defining the construction of each tree,

K is the total number of trees in the forest,

is the prediction of the

k-th decision tree, and

represents the randomness in tree construction, including the bootstrap sample and the random subset of predictor variables used for splitting nodes.

In addition, a link prediction framework is implemented to identify novel drug candidates by estimating the likelihood of interactions between drug molecules and target proteins. Comparative analyses with existing drugs are conducted to evaluate predicted binding affinity and structural similarity. Finally, the contribution of each graph-theoretical descriptor is examined to identify the most influential features for accurate drug prediction.

5. Numerical Results

In this section, we present a comparison of our main results. We applied three approaches to predict key chemical properties of drug compounds, focusing on molar volume and molecular weight: (i) baseline linear model, (ii) linear regression with training data, and (iii) Random Forest regression. The dataset was preprocessed by handling missing values and normalising features to ensure reliable predictions. To prevent overfitting, the data were split into training and test sets for the machine learning models, while baseline linear regression was applied to the full dataset without training.

The baseline linear model provides a simple, interpretable reference for understanding linear relationships between molecular descriptors and target properties. Linear regression with training data improves predictive performance by fitting model parameters, whereas Random Forest, an ensemble learning method, captures complex and nonlinear dependencies. Model performance was evaluated using metrics such as the coefficient of determination (), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE). Feature importance analysis was also conducted to assess the contribution of different molecular descriptors to the prediction of molar volume and molecular weight. Comparing the outputs of these models demonstrates the effectiveness of graph-theoretical descriptors and provides valuable insights for molecular modelling and CAD drug characterisation.

Based on the previous study, we have considered the two physicochemical properties named molar volume and molecular weight. These two properties have a high level of predictive accuracy for the degree-based topological indices, as shown in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. It is important to highlight that the evaluation of these indices requires only two structural parameters: the number of vertices v and the number of edges e.

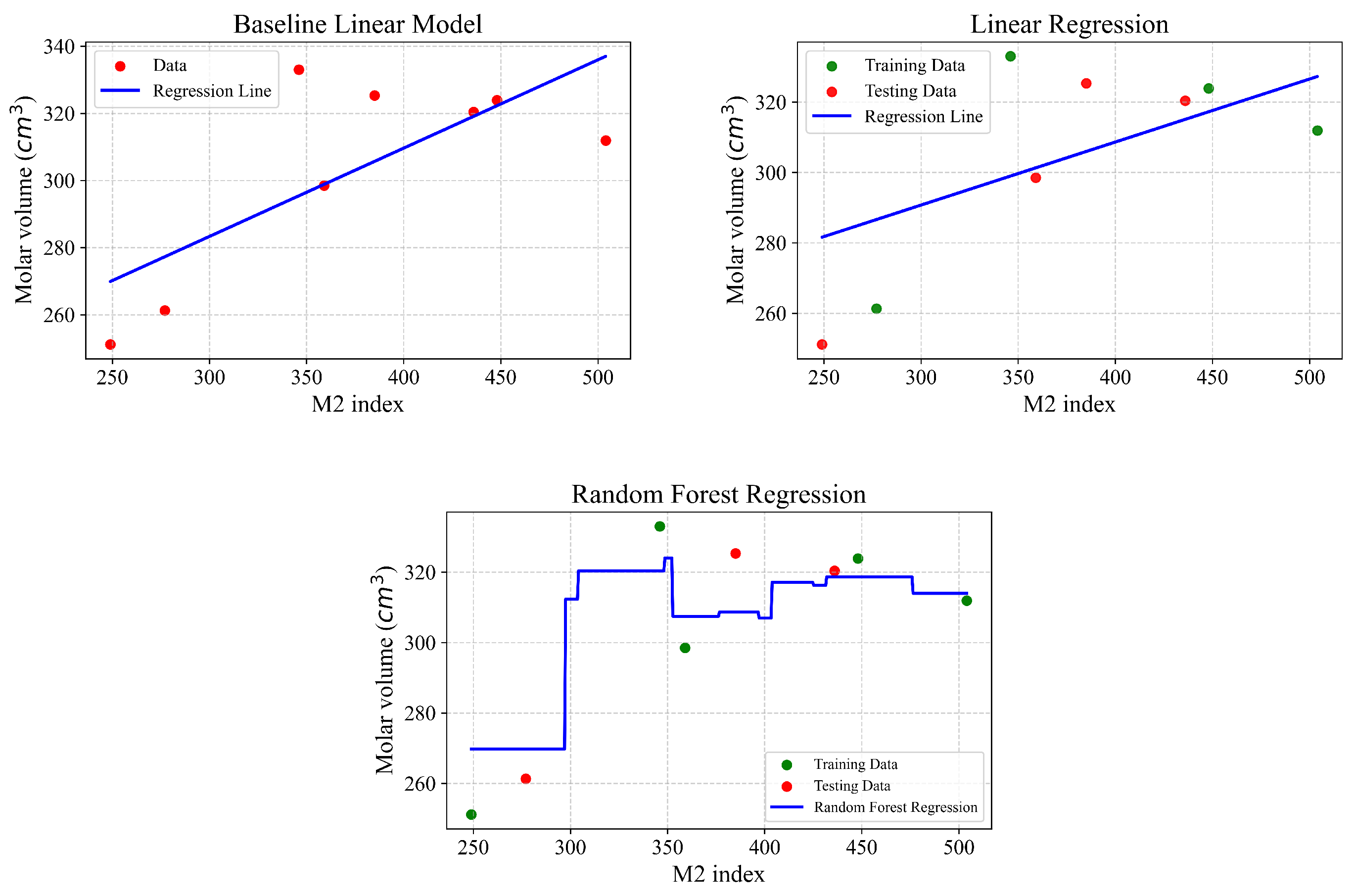

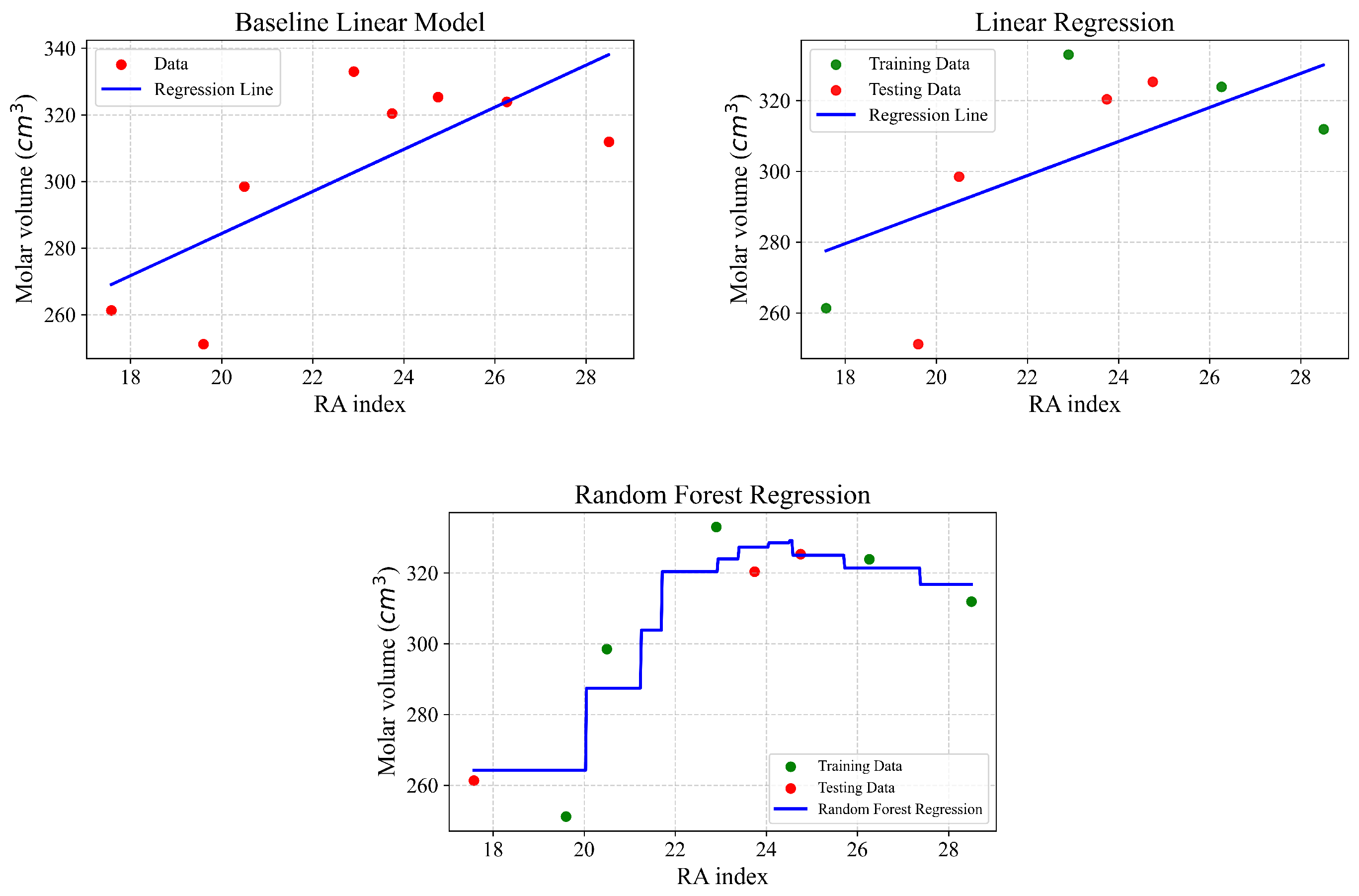

5.1. The Predicative Model of Considered Topological Indices and Molar Volume

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 summarise the performance of different classes of regression models and topological descriptors in predicting the molar volume of the drugs. It can be seen from

Table 3 and

Table 5 that the linear regression model has the highest predictive accuracy. Traditional degree-based and distance-based indices, such as the first general temperature index and the second general temperature index, exhibit strong correlations, with correlation values of 0.9204 and 0.9199, respectively. Our results attain the highest predictive accuracy with correlation values of 0.964 and 0.960. This highlights the superiority of the considered topological indices and demonstrates the advancement contributed by the present study. Similarly,

Table 4 and

Table 5 show that Random Forest attains the highest predictive accuracy with correlation values of 0.988 and 0.977. A graphical comparison of the predicted and actual molar volume values for each topological index is provided in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6.

Table 3.

The results of machine learning methods regarding ABC index and molar volume.

Table 3.

The results of machine learning methods regarding ABC index and molar volume.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.858 | 0.737 | 218.64 | 12.34 |

| Linear regression | 0.964 | 0.929 | 47.496 | 6.726 |

| Random Forest | 0.951 | 0.865 | 111.43 | 8.09 |

Table 4.

The results of machine learning methods regarding M1 index and molar volume.

Table 4.

The results of machine learning methods regarding M1 index and molar volume.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.764 | 0.585 | 345.64 | 14.69 |

| Linear regression | 0.951 | 0.904 | 64.325 | 6.871 |

| Random Forest | 0.988 | 0.841 | 131.27 | 9.35 |

Table 5.

The results of machine learning methods regarding M2 index and molar volume.

Table 5.

The results of machine learning methods regarding M2 index and molar volume.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.737 | 0.544 | 379.80 | 15.038 |

| Linear regression | 0.924 | 0.855 | 97.825 | 8.066 |

| Random Forest | 0.977 | 0.737 | 216.97 | 11.76 |

Table 6.

The results of machine learning methods regarding RA index and molar volume.

Table 6.

The results of machine learning methods regarding RA index and molar volume.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.74 | 0.549 | 374.9 | 16.16 |

| Linear regression | 0.960 | 0.922 | 52.433 | 7.101 |

| Random Forest | 0.956 | 0.883 | 96.52 | 8.82 |

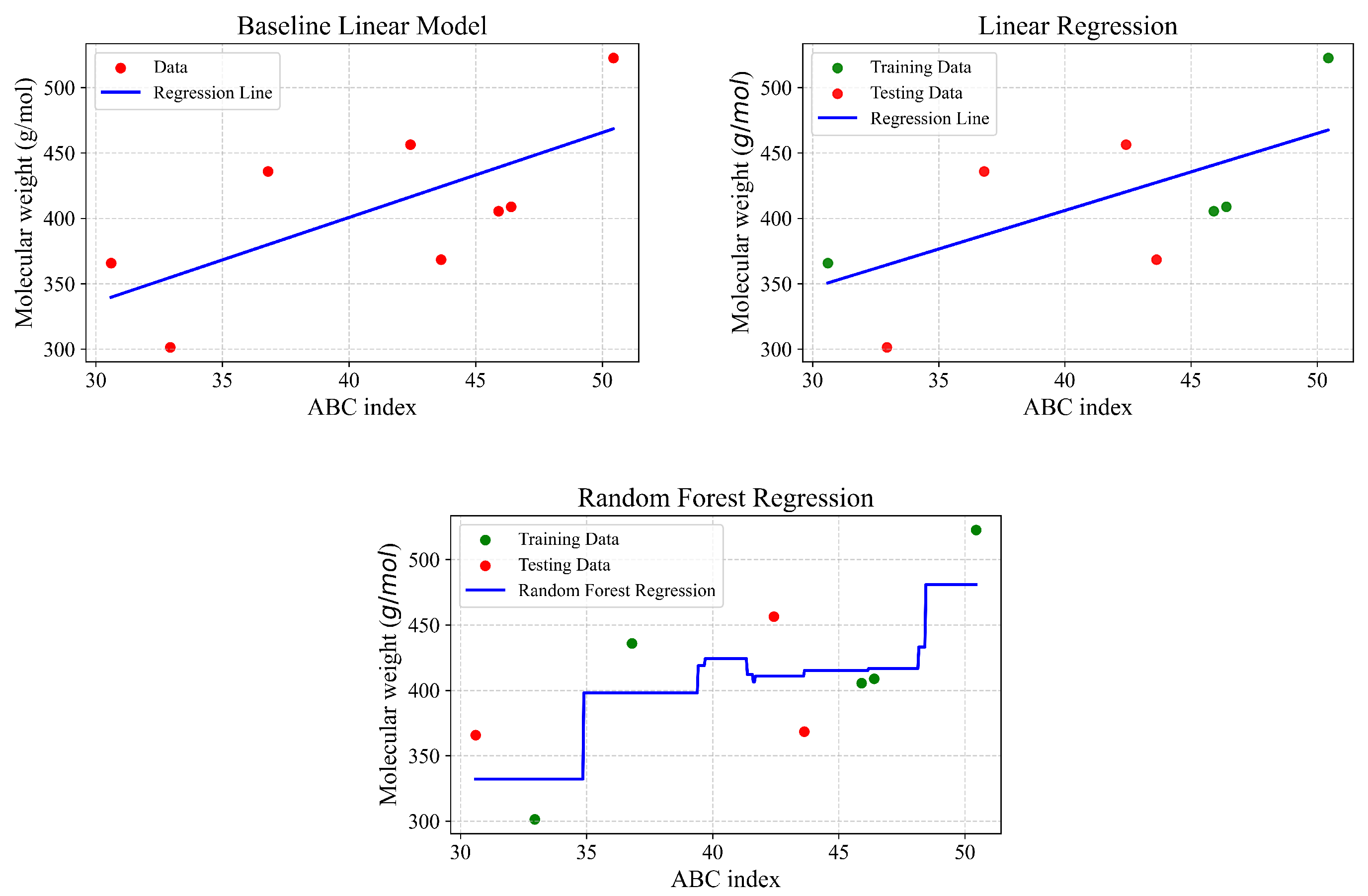

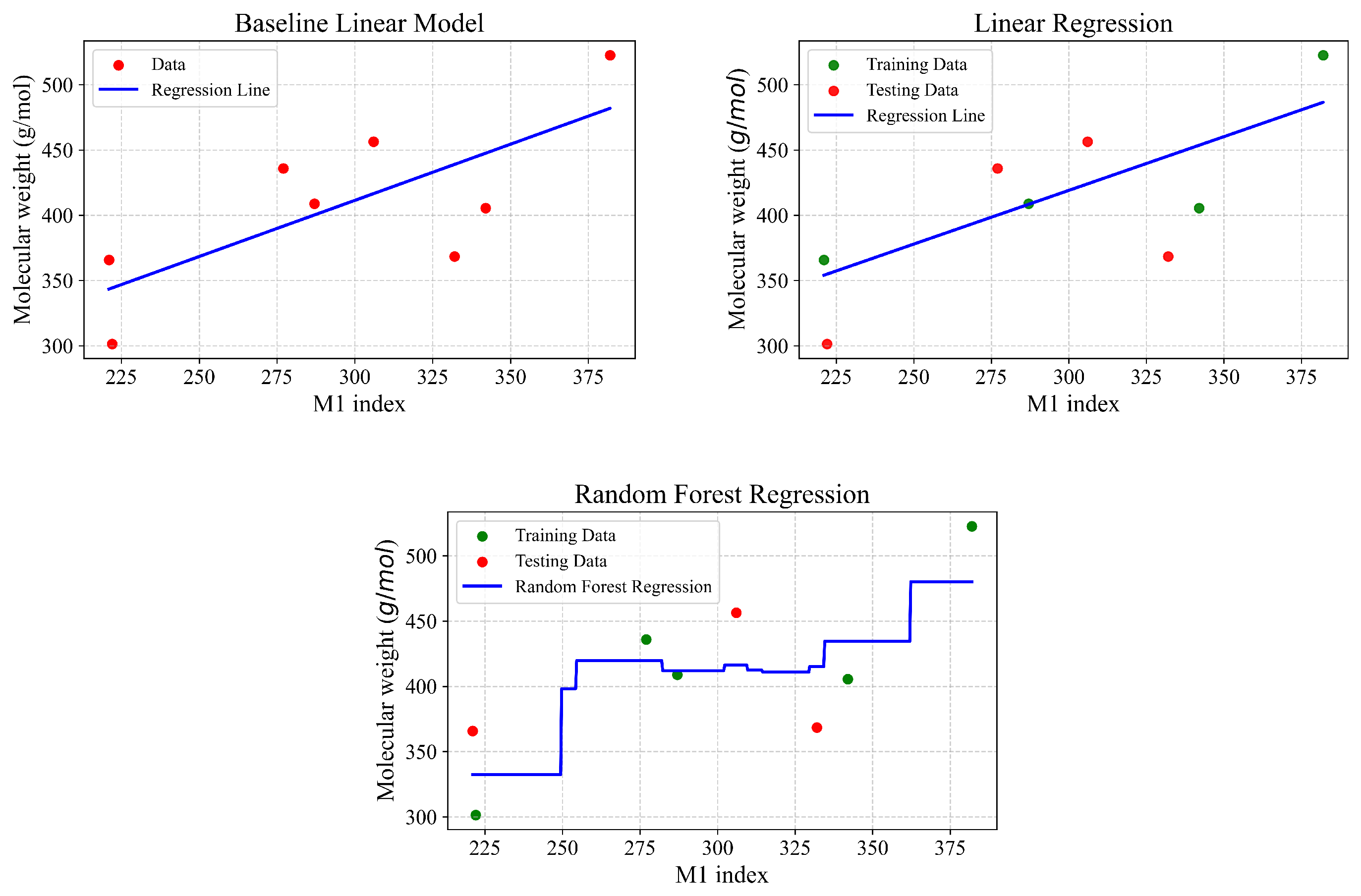

5.2. The Predicative Model of the Considered Topological Indices and Molecular Weight

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10 summarise the performance of different classes of regression models and the topological descriptors in predicting the molecular weight of the drugs. It can be seen from these tables that the Random Forest model has the highest predictive accuracy. Traditional degree-based and distance-based indices, such as the first general temperature index and the second general temperature index, exhibit strong correlations, with correlation values of 0.910 and 0.912, respectively. Our results attain the highest predictive accuracy, with correlation values of 0.959, 0.963, 0.962, and 0.929. This highlights the superiority of the considered topological indices and demonstrates the advancement contributed by the present study. The graphical comparison of these indices for molecular weight are also given in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

Table 7.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the ABC index and molecular weight.

Table 7.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the ABC index and molecular weight.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.682 | 0.465 | 2068.68 | 44.04 |

| Linear regression | 0.762 | 0.581 | 1430.5 | 35.102 |

| Random Forest | 0.959 | 0.830 | 853.95 | 25.57 |

Table 8.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the M1 index and molecular weight.

Table 8.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the M1 index and molecular weight.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.732 | 0.536 | 1793.20 | 38.88 |

| Linear regression | 0.852 | 0.725 | 938.742 | 24.088 |

| Random Forest | 0.963 | 0.846 | 773.48 | 24.32 |

Table 9.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the M2 index and molecular weight.

Table 9.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the M2 index and molecular weight.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.739 | 0.546 | 1755.49 | 38.16 |

| Linear regression | 0.844 | 0.713 | 980.868 | 25.306 |

| Random Forest | 0.962 | 0.863 | 684.89 | 22.22 |

Table 10.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the RA index and molecular weight.

Table 10.

Results of machine learning methods regarding the RA index and molecular weight.

| Type of Regression | r | | MSE | MAE |

|---|

| Baseline linear model | 0.711 | 0.506 | 1910.80 | 39.41 |

| Linear regression | 0.825 | 0.681 | 1090.342 | 27.539 |

| Random Forest | 0.929 | 0.800 | 1003.87 | 28.43 |

6. Conclusions and Discussion

This study presents a computational framework integrating topological analysis with predictive modelling to investigate drugs for coronary artery disease (CAD) and atrial fibrillation (AF). Eight AF drugs, primarily beta-blockers, were analysed using topological indices (T-indices) to characterise their structural and physicochemical properties, including molar volume, molecular weight, complexity, boiling point, and flash point. Three predictive approaches were applied: (1) a baseline linear model, applied directly to the full dataset as a reference, providing interpretable correlations between T-indices and molecular properties; (2) a machine learning-based linear regression model, which improved predictive performance; and (3) Random Forest regression, which captured potential nonlinear relationships and enhanced accuracy for selected indices. The high predictability of molar volume reflects its direct representation of a molecule’s three-dimensional size and shape, which influence pharmaceutical properties such as solubility and membrane permeability. Topological indices effectively encode these structural features, explaining the strong performance of all models.

Despite these promising results, this study has several limitations. The dataset is small, comprising only eight beta-blocker drugs, which limits the generalisability of the predictions and increases the risk of overfitting, particularly for ensemble methods such as Random Forest. The absence of experimental or biological validation further restricts the applicability of the findings. Consequently, the results should be interpreted as preliminary insights rather than definitive conclusions. Future work should address these limitations by incorporating larger and more diverse drug datasets to improve model validation and statistical robustness. Advanced computational methods, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, could provide more detailed structural and dynamic information. Finally, integrating experimental or clinical validation will be essential to confirming the practical relevance of these predictive models and support their application in AI-driven drug discovery and personalised medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.A.E. and S.N.; methodology, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; software, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; validation, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; formal analysis, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; investigation, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; resources, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; data curation, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; visualisation, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; supervision, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; project administration, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, N.A.E., S.N. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Internal Fund Project, Oman, grant number No. UoN/28/IF/2025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Internal Fund Project, Oman (Grant No. UoN/28/IF/2025). They also extend their sincere appreciation to the administration of the University of Nizwa for their continuous encouragement and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mansha, M.; Ahmad, S.; Raza, Z. Eccentric indices based QSPR evaluation of drugs for schizophrenia treatment. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ashraf, T.; Saleem, M.T.; Mahmoud, E.E.; Ali, K.; Zaman, S.; Belay, M.B. Computational approaches in drug chemistry leveraging python powered QSPR study of antimalaria compounds by using artificial neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.F.; Hashem, A.F.; Hussain, M.; Siddiqui, M.K. A statistical correlation of entropy measures and zagreb indices in antizeolite networks via pearson analysis. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 6985–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.J.; Jurs, P.C. Chemical Applications of Graph Theory. Part I. Fundamentals and Topological Indices. J. Chem. Educ. 1988, 65, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajtlowicz, S. On Conjectures of Graffiti. Ann. Discrete Math. 1988, 38, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Awais, H.M.; Javaid, M.; Siddiqui, M.K. Multiplicative Zagreb Indices of Molecular Graphs. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 5294198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasi, M.; Raeisi, G.; Taeri, B. Wiener Index of Some Graph Operations. Discret. Appl. Math. 2012, 160, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawhari, Q.M.; Rehman, M.; Ahmed, W.; Ahmad, A.; Koam, A.N.A. Exploring the potential of artificial neural networks in predicting physicochemical characteristics of anti-biofilm compounds from 2D and 3D structural information. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2025, 39, 2550157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ashraf, T.; Zaman, S.; Ullah, A.; Khalid, F. A hybrid computational framework for antidepressant drug design integrating machine learning algorithms and molecular modeling. Chem. Pap. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Naeem, M.; Rahman, J.; Saleem, A.V. QSPR Study of Ve-Degree Based End Vertice Edge Entropy Indices with Physio-Chemical Properties of Breast Cancer Drugs. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2023, 43, 4170–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Z.; Arockiaraj, M.; Maaran, A.; Kavitha, S.R.J.; Balasubramanian, K. Topological Entropy Characterization, NMR and ESR Spectral Patterns of Coronene-Based Transition Metal Organic Frameworks. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 13371–13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutman, I.; Trinajstić, N. Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total π-electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1972, 17, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.; Ahmad, A.; Azeem, M.; Koam, A.N.A. Assessment of the artificial neural networks based on spherical fuzzy information. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 18347–18365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koam, A.N.A.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Ahmad, A.; Nadeem, M.F.; Masmali, I. M-polynomials characterization n-dimensional of triphenylene-based metal and covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 7643–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takkavatakarn, K.; Oh, W.; Cheng, E.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Chan, L. Machine Learning Models to Predict End-Stage Kidney Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 4. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poojary, P.; Shenoy, G.B.; Swamy, N.N.; Ananthapadmanabha, R.; Sooryanarayana, B.; Poojary, N. Reverse Topological Indices of Some Molecules in Drugs Used in the Treatment of H1N1. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancan, M. On Ev-Degree and Ve-Degree Topological Properties of Tickysim Spiking Neural Network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 8429120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, S.; Zaman, S.; Nawaz, S.; Eshtewy, N.A. Atrial fibrillation drug structural analysis and predictive modeling employing machine learning methods. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ali, K.; Zaman, S.; Raza, A. Molecular insights into anti-Alzheimer’s drugs through predictive modeling using linear regression and QSPR analysis. Modern Phys. Lett. B 2024, 38, 2450260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dayel, I.; Khan, M.A.; Hanif, M.F.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Hanif, S.; Gegbe, B. A graph-based computational approach for modeling physicochemical properties in drug design. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamani, S.; Perigidad, D.; Jamagoud, S.; Maled, Y.; Gavade, S. QSPR Analysis of Certain Degree-Based Topological Indices. J. Stat. Appl. Probab. 2017, 6, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, H.; Koam, A.N.A.; Nadeem, M.F.; Ahmad, A. Topological Insights into Nanostar Dendrimers by Computing the Augmented Zagreb Index. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2025, 28, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Qasim, M.; Zaman, S.; Khan, A. Computational and Comparative Aspects of Two Carbon Nanosheets with Respect to Some Novel Topological Indices. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaira, M.; Belhenniche, A.; Chertovskih, R. Enhancing DDoS Attacks Mitigation Using Machine Learning and Blockchain-Based Mobile Edge Computing in IoT. Computation 2025, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erciyes, K. Graph-Theoretical Analysis of Biological Networks: A Survey. Computation 2023, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, I.; Furtula, B.; Katanić, V. Randić Index and Information. AKCE Int. J. Graphs Combin. 2018, 15, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Trinajstić, N. On a novel connectivity index. J. Math. Chem. 2009, 46, 1252–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujošević, S.; Popivoda, G.; Kovijanić Vukićević, Ž; Furtula, B.; Škrekovski, R. Arithmetic–Geometric Index and Its Relations with Geometric–Arithmetic Index. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 391, 125706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdel, G.H.; Rezapour, H.; Sayadi, A.M. The Hyper-Zagreb Index of Graphs. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2013, 70, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Furtula, B.; Gutman, I. A forgotten topological index. J. Math. Chem. 2015, 53, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galushka, M.; Swain, C.; Browne, F.; Mulvenna, M.D.; Bond, R.; Gray, D. Prediction of chemical compounds properties using a deep learning model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 13345–13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.B. The Organic Chemistry of Drug Design and Drug Action, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torng, W.; Altman, R.D. Graph Convolutional Networks for Predicting Drug–Target Interactions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, M.H. Random-Forest Model for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction via Kullbeck–Leibler Divergence. J. Cheminform. 2022, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Workflow of the QSPR model development process for coronary artery disease drugs, including molecular transformation, computation of topological indices, regression and machine learning analysis, and evaluation of correlation results.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the QSPR model development process for coronary artery disease drugs, including molecular transformation, computation of topological indices, regression and machine learning analysis, and evaluation of correlation results.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of drugs for coronary artery disease treatment: Brilinta, Amlodipine, Xarelto, Brilinta, Perindopril, Isoxsuprine, Azilsartan, and Metolazone.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of drugs for coronary artery disease treatment: Brilinta, Amlodipine, Xarelto, Brilinta, Perindopril, Isoxsuprine, Azilsartan, and Metolazone.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of regression models for the ABC index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of regression models for the ABC index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 4.

Comparison of regression models for the M1 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from regression, linear regression, and Random Forest models.

Figure 4.

Comparison of regression models for the M1 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from regression, linear regression, and Random Forest models.

Figure 5.

Comparison of regression models for the M2 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 5.

Comparison of regression models for the M2 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 6.

Comparison of regression models for the RA index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 6.

Comparison of regression models for the RA index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 7.

Comparison of regression models for the ABC index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 7.

Comparison of regression models for the ABC index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 8.

Comparison of regression models for the M1 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 8.

Comparison of regression models for the M1 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 9.

Comparison of regression models for the M2 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 9.

Comparison of regression models for the M2 index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 10.

Comparison of regression models for the RA index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Figure 10.

Comparison of regression models for the RA index. Each subplot represents the predicted and observed relationships obtained from baseline linear model, linear regression, and random forest models.

Table 1.

Physical and characteristic properties of the candidate drugs.

Table 1.

Physical and characteristic properties of the candidate drugs.

| Drug Name | Molar Volume (cm3) | Boiling Point (°C) | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Complexity | Flash Point (°C) |

|---|

| Lisinopril | 323.9 | 666.4 | 405.495 | 550 | 356.9 |

| Amlodipine | 333 | 527.2 | 408.879 | 647 | 272.6 |

| Xarelto | 298.5 | 732.6 | 435.879 | 645 | 396.9 |

| Brilinta | 311.9 | 777.6 | 522.6 | 736 | 424 |

| Perindopril | 320.4 | 537.4 | 368.474 | 524 | 278.8 |

| Isoxsurprine | 251.16 | 484.51 | 301.4 | 299 | 246.6 |

| Azilsartan | 325.33 | 747.9 | 456.4 | 783 | 406.15 |

| Metolazone | 261.3 | 613.6 | 365.8 | 594 | 324.9 |

Table 2.

Molecular descriptors for the candidate drugs.

Table 2.

Molecular descriptors for the candidate drugs.

| Index | Lisinopril | Amlodipine | Xarelto | Brilinta | Perindopril | Isoxsurprine | Azilsartan | Metolazone |

|---|

| 45.9 | 46.4 | 36.8 | 50.44 | 43.63 | 32.94 | 42.42 | 30.6 |

| 342 | 287 | 277 | 382 | 332 | 222 | 306 | 221 |

| 448 | 346 | 359 | 504 | 436 | 249 | 385 | 277 |

| 26.26 | 22.9 | 20.5 | 28.5 | 23.74 | 19.6 | 24.75 | 17.58 |

| S | 26.38 | 23.07 | 21.5 | 29.3 | 24.05 | 19.22 | 25.6 | 17.9 |

| 55.07 | 47.7 | 46.3 | 62.3 | 50.5 | 38.58 | 54.47 | 37.68 |

| H | 23.18 | 20.26 | 18.69 | 25.64 | 20.54 | 17.39 | 22.85 | 15.8 |

| 2038 | 1609 | 1589 | 2266 | 2034 | 1190 | 1672 | 1237 |

| F | 1142 | 917 | 871 | 1258 | 1162 | 692 | 902 | 683 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |